Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, is a growing global health challenge. This study examines the global burden of MASLD from 1990 to 2021 and projects data for 2045.

Materials and MethodsUsing data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2021, the study analyzed MASLD across 204 countries from 1990 to 2021, focusing on prevalence, incidence, deaths, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Linear and Joinpoint regression assessed trends, an age-period-cohort model evaluated health outcomes, and a Bayesian model forecasted future cases.

ResultsIn 2021, approximately 1.27 billion people globally had MASLD, with a higher prevalence in males (51.41 %). There were 48.35 million new cases, primarily in males (52.24 %). The age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR) increased from 12,085.09 in 1990 to 15,018.07 per 100,000 in 2021 (AAPC 0.71). The age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) rose from 475.54 to 593.28 per 100,000 (AAPC 0.71). MASLD caused 138,328 deaths, with females experiencing higher mortality (52.18 %). East Asia, South Asia, and North Africa/Middle East had the highest prevalence and incidence rates, while Western Europe showed the fastest growth. By 2045, ASIR is projected to reach 928.10 per 100,000, resulting in 667.58 million new cases, predominantly affecting males.

ConclusionsMASLD poses a significant burden with notable gender and regional disparities. The projected increase by 2045 underscores the need for urgent public health interventions and targeted strategies to mitigate this growing epidemic.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, has emerged as a significant global public health challenge [1–3]. Characterized by excessive hepatic fat accumulation without significant alcohol consumption, MASLD encompasses a spectrum of liver conditions ranging from simple steatosis to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, which can progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [4,5]. Over the past three decades, the prevalence of MASLD has increased dramatically, driven by rising rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome [6–8].

MASLD is now recognized as a leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, affecting approximately 25 % of the global population [9]. This increase is closely linked to the rapid adoption of sedentary lifestyles and high-calorie diets, particularly in urbanized and industrialized regions [10,11]. Beyond liver-related morbidity and mortality, MASLD significantly contributes to the global burden of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and other metabolic disorders [12,13]. Understanding the global burden and future trends of MASLD is crucial for policymakers, healthcare providers, and researchers to develop and implement effective strategies for prevention, early detection, and management of this burgeoning epidemic.

Previous studies have assessed the global burden of MASLD from 1990 or 2000 to 2019 but have not adequately explored inflection points and future projections, leaving a significant gap in understanding its evolution and effects over time [14–17]. This study addresses this gap by evaluating the global, regional, and national burden of MASLD from 1990 to 2021, using updated epidemiological analyses and data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) database 2021. By utilizing combined joinpoint and age-period-cohort methods, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the prevalence, incidence, and outcomes of MASLD across various populations and geographies. This evaluation will aid in refining public health strategies and allocating resources to areas with the highest burden, ultimately contributing to better management and prevention of MASLD on a global scale.

2Materials and Methods2.1Data sourceOur analysis of the GBD Study 2021 utilized cross-sectional data from the Global Health Data Exchange, encompassing the global burden of 371 diseases and injuries, and 88 risk factors across 21 geographic regions and 204 countries from 1990 to 2021 [18]. The study focused on individuals with MASLD. Data included prevalence, incidence, deaths, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), and risk factors, with corresponding 95 % uncertainty intervals (UI). The use of GBD database data is exempt from informed consent as all data are publicly available and de-identified. This study followed STROBE reporting guidelines and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Affiliated Hospital of Shandong Second Medical University.

2.2Sociodemographic indexThe Sociodemographic Index (SDI) measures development levels based on fertility rate, education, and per capita income with higher values indicating greater development [19]. This study categorizes countries into five SDI levels [20].

2.3Linear and joinpoint regressionWe computed the mean Estimated Annual Percentage Changes (EAPCs) using linear regression. The Joinpoint regression model identifies turning points in disease trends and calculates the Annual Percent Change (APC) and the Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC). Starting with a log-linear model, it uses a grid search to find joinpoints, selecting the one with the minimum Mean Squared Error. Monte Carlo permutation tests determine the optimal model with 0 to 5 joinpoints. APC is calculated as (e^β - 1) * 100 %, where β is the regression coefficient. AAPC, derived from the weighted average of APCs, reflects the overall trend from 1990 to 2021 [21,22].

2.4Age-period-cohort modelThe age-period-cohort model evaluates how age, period, and cohort influence health outcomes using the log-linear regression equation: log(Yi) = μ + α⋅agei + β⋅periodi + γ⋅cohorti + ϵ. Here, Yi represents the MASLD prevalence, incidence, death and DALYs rate, μ is the intercept, and α, β, γ are coefficients for age, period, and cohort, with ϵ as the residual. This model helps disentangle the contributions of these effects on health trends [23].

2.5Forecasting model developmentFor forecasting, we used global incidence data from 1990 to 2021 in five-year intervals. Using a Bayesian-age-period-cohort model with the R package (version 0.0.36), we predicted the disease burden from 2022 to 2045 [24]. We also conducted sensitivity analyses to better validate projections.

2.6Statistical analysisTime trends of disease burden were analyzed using EAPC and AAPC. Analyses and visualizations were conducted with R Studio (version 4.3.3). P-values were two-sided, with P < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

2.7Ethical statementsThis study is based on publicly available, de-identified data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2021. Therefore, ethical approval and informed consent were not required. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

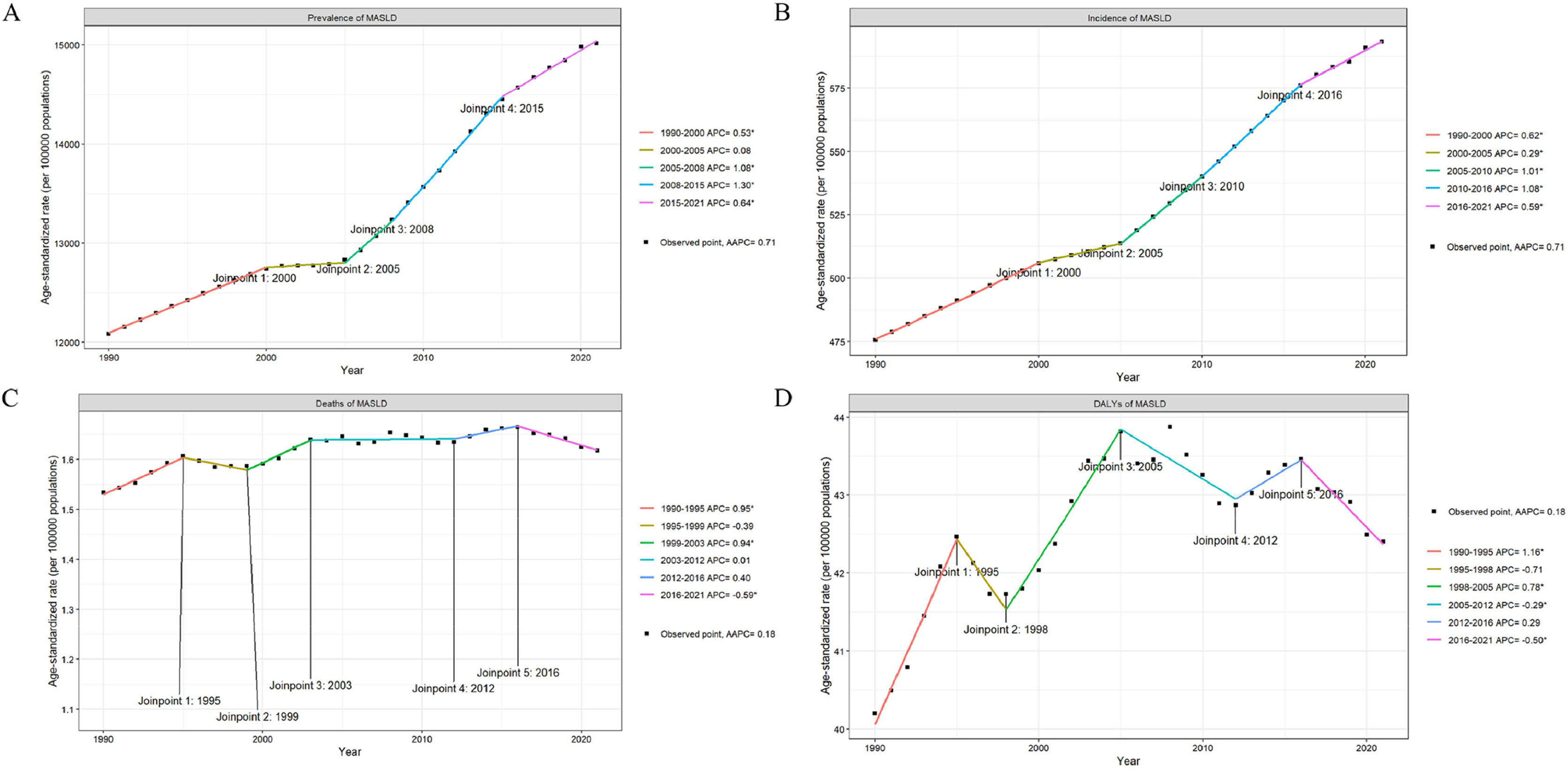

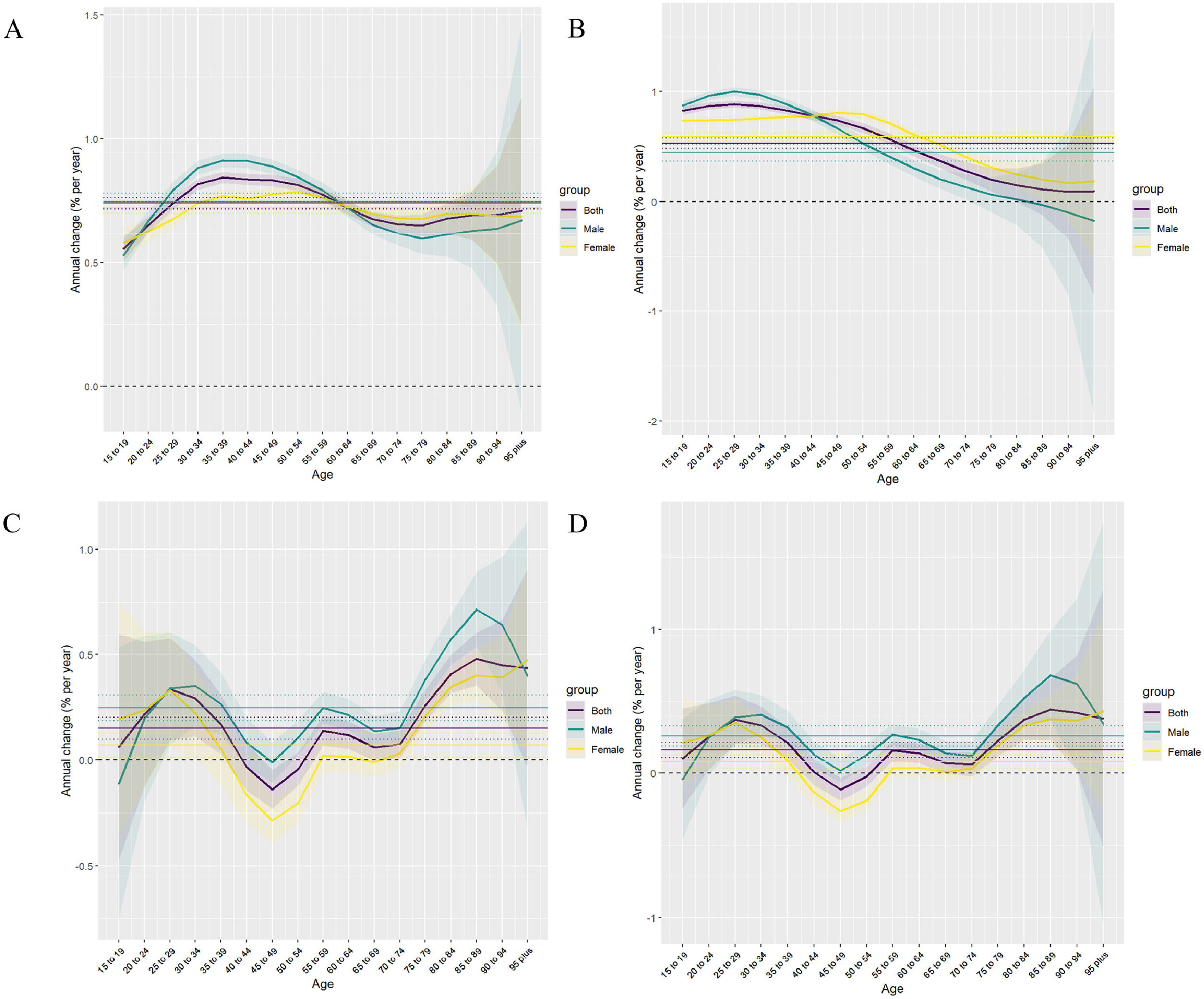

3Results3.1Global trendsIn 2021, the number of MASLD cases was 1267,867,997 (95 % UI, 1157,934,071–1380,435,423), of which 651,868,284 (51.41 %) were male and 615,999,714 (48.59 %) were female. The incidence of MASLD was 48,353,272 (95 % UI, 44,229,139–52,358,017), of which 25,232,811 (52.18 %) were male and 23,120,461 (47.82 %) were female. The ASPR increased from 12,085.09 (95 % UI, 11,058.41–13,184.29) per 100,000 in 1990 to 15,018.07 (95 % UI, 13,756.47–16,361.44) per 100,000 by 2021 (AAPC 0.71 [95 % CI, 0.54–0.73]), with the largest increase occurring in the 2008–2015 period, corresponding to an APC of 1.30 (P < 0.05). There was an increasing trend in ASPR in both sexes. The ASIR for MASLD increased from 475.54 cases per 100,000 (95 % UI, 432.59–518.19) in 1990 to 593.28 cases per 100,000 (95 % UI, 542.72–643.70) in 2021 (AAPC 0.71 [95 % CI, 0.69–0.73]), with the largest increase in 2010–2016, corresponding to an APC of 1.08 (95 % CI, 1.03–1.13) (P < 0.05). There was also an increasing trend in ASIR in both males and females (Fig. 1A,1B;Fig. 2A,2B; Supplementary Table 1, 2).

In 2021, MASLD caused 138,328 deaths (95 % UI, 108,288–173,905), with 66,148 (47.82 %) males and 72,180 (52.18 %) females. DALYs totaled 3667,267 (95 % UI, 2903,576–4607,307), with 1872,885 (51.07 %) males and 1794,382 (48.93 %) females. The ASMR rose from 1.53 (95 % UI, 1.17–1.97) per 100,000 in 1990 to 1.62 (95 % UI, 1.27–2.02) in 2021 (AAPC 0.18 [95 % CI, 0.04 to 0.32]), peaking from 1990 to 1995 with an APC of 0.95 (95 % CI, 0.65–1.24) (P < 0.05) and decreasing from 2016 to 2021 with an APC of −0.59 (95 % CI, −0.85 to −0.33) (P < 0.05). Both male and female ASMRs increased. The ASDR rose from 40.20 (95 % UI, 30.73–52.23) per 100,000 in 1990 to 42.40 (95 % UI, 33.60–53.31) in 2021 (AAPC 0.18 [95 % CI, 0.01–0.35]), with the largest increase from 1990 to 1995 (APC 1.16 [95 % CI, 0.83–1.48], P < 0.05) and the largest decrease from 2016 to 2021 (APC −0.5 [95 % CI, −0.79 to −0.22], P < 0.05). ASDR for both genders also increased (Fig. 1C,1D;Fig. 2C,2D; Supplementary Table 3, 4).

3.2SDI regional trendsIn 2021, the Middle SDI region had the highest MASLD prevalence and incidence, with 453,616,040 (414,597,794–494,648,033) and 17,017,313 (15,552,700–18,416,003) cases, respectively. It also recorded the highest ASPR at 16,589.92 (15,168.29–18,069.08) and ASIR at 656.97 (602.08–712.86). From 1990 to 2021, the High SDI region saw the fastest growth in ASPR and ASIR, with EAPCs of 1.09 (1.05–1.14) and 1.00 (0.95–1.05). The Middle SDI region also had the highest MASLD deaths and DALYs number in 2021, with 46,547 (36,615–58,522) and 1260,024 (991,414–1590,487). The Low-middle SDI region had the highest ASMR at 1.87 (1.39–2.41) and ASDR at 47.65 (35.77–61.75). From 1990 to 2021, the Low SDI region experienced the fastest decline in ASMR and ASDR, with EAPCs of −0.32 (−0.36 to −0.28) and −0.42 (−0.46 to −0.38) (Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Table1–4).

3.3Geographic regional trendsIn 2021, East Asia, South Asia, and North Africa and the Middle East had the highest global MASLD prevalence and incidence, with East Asia having the highest prevalence at 301,408,386 (274,406,342–328,824,039) and South Asia the highest incidence at 10,765,351 (9758,064–11,817,449). North Africa and the Middle East recorded the highest ASPR at 27,686.69 (25,586.92–29,914.62) and ASIR at 1037.64 (963.01–1109.65). Western Europe experienced the fastest growth in ASPR and ASIR, with EAPCs of 0.98 (0.93–1.02) and 0.73 (0.69–0.78) The Central Sub-Saharan Africa region had the slowest growth in ASPR and in ASIR (Supplementary Table 1, 2).

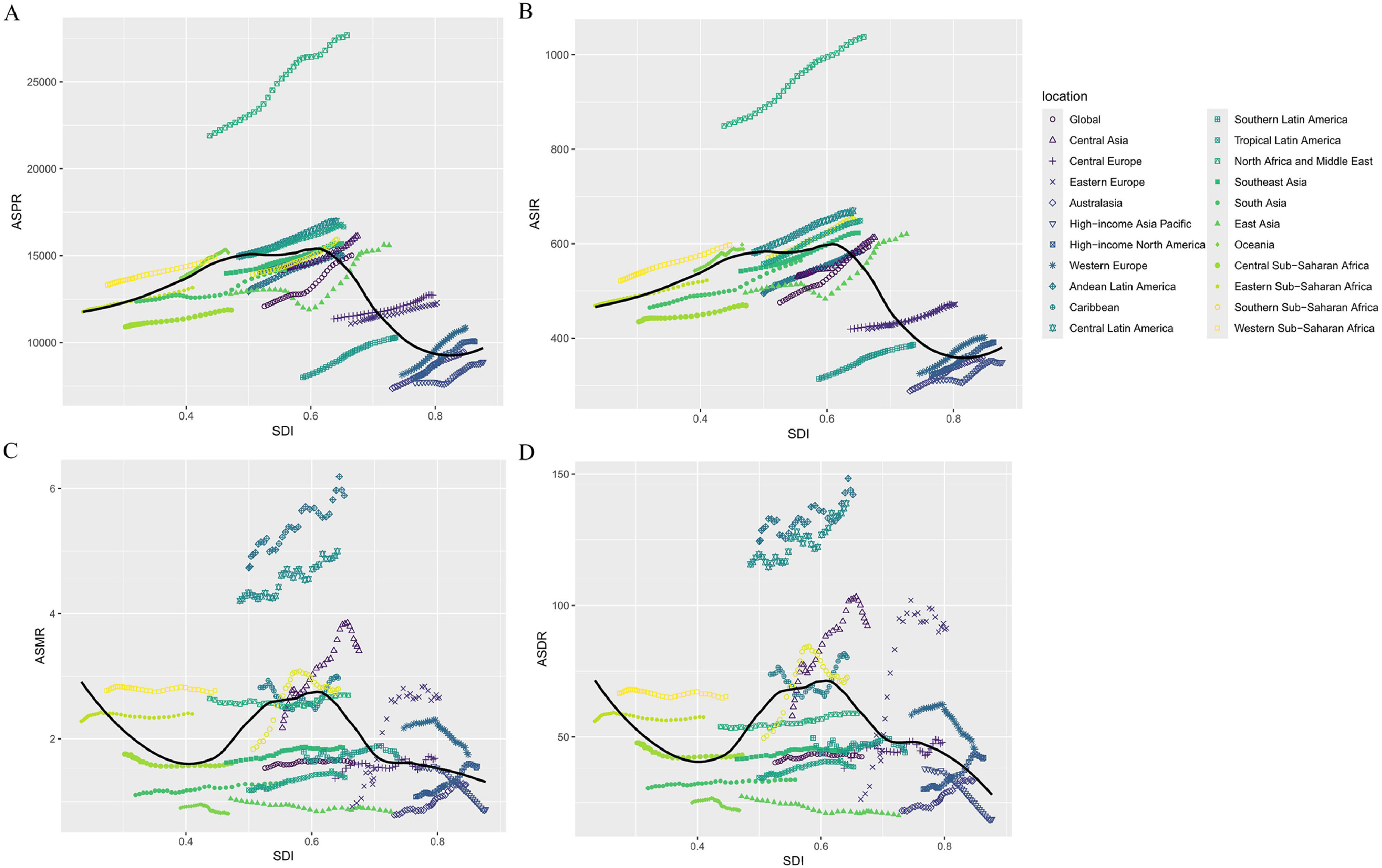

In 2021, the global SDI was 0.67, with an ASPR of 15,018.07. High-income Asia Pacific had the highest SDI at 0.88 and an ASPR of 8885.73, while Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa had the lowest SDI at 0.41 and an ASPR of 13,162.12. Of the 21 regions, 9 had an ASPR above the global level, with North Africa and the Middle East being the highest (SDI 0.66), and 12 had an ASPR below the global level, with High-income Asia Pacific being the lowest (SDI 0.88). The global ASIR was 593.28. High-income Asia Pacific had an SDI of 0.88 and an ASIR of 348.79, while Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa had an SDI of 0.41 and an ASIR of 522.51. 8 regions had an ASIR above the global level, with North Africa and the Middle East being the highest (SDI 0.66), and 13 regions had an ASIR below the global level, with High-income Asia Pacific being the lowest (SDI 0.88) (Fig. 3A,3B).

In 2021, South Asia and East Asia had the highest global MASLD deaths and DALYs, with South Asia leading at 18,670 deaths (13,608–24,921) and 540,638 DALYs (397,352–722,267). Andean Latin America, Central Latin America, and Central Asia had the highest ASMR and ASDR, with Andean Latin America recording the highest ASMR at 5.89 (4.03–8.07) and ASDR at 142.16 (98.60–198.78). Eastern Europe had the fastest-growing ASMR and ASDR, with EAPCs of 3.58 (2.95 to 4.22) and 4.09 (3.28 to 4.9). Conversely, High-income Asia Pacific saw the fastest declines in ASMR and ASDR, with EAPCs of −2.09 (−2.24 to −1.94) and −2.54 (−2.68 to −2.39) (Supplementary Table 3, 4).

Of the 21 geographic regions, 13 have an ASMR above the global level, with Andean Latin America being the highest, corresponding to an SDI of 0.65. 8 regions are below the global level, with Oceania being the lowest, corresponding to an SDI of 0.47. The ASDR is above global levels in 14 regions, with Andean Latin America being the highest, corresponding to an SDI of 0.65. It is below global levels in 7 regions, with High-income Asia Pacific being the lowest, corresponding to an SDI of 0.88 (Fig. 3C,3D).

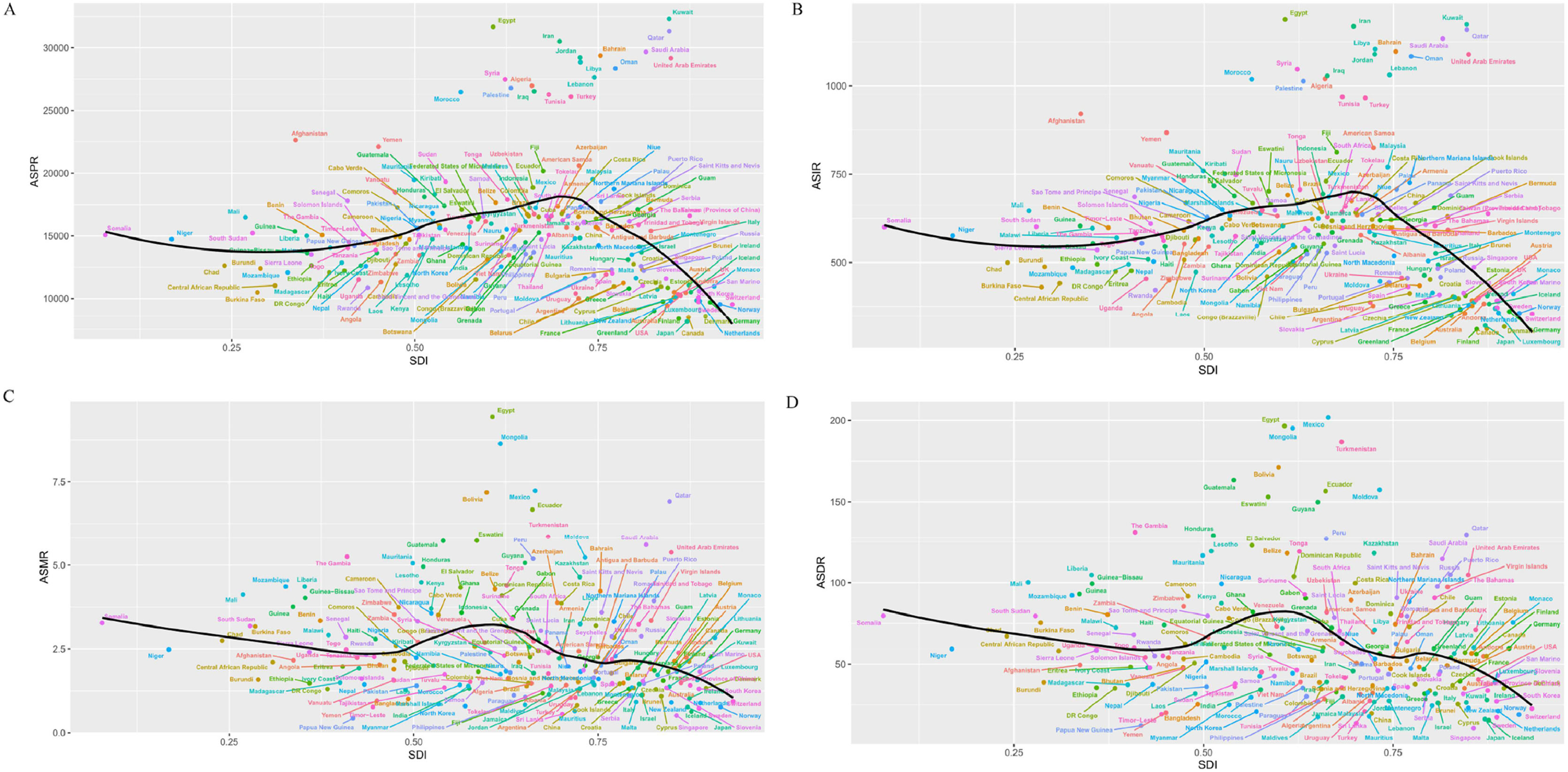

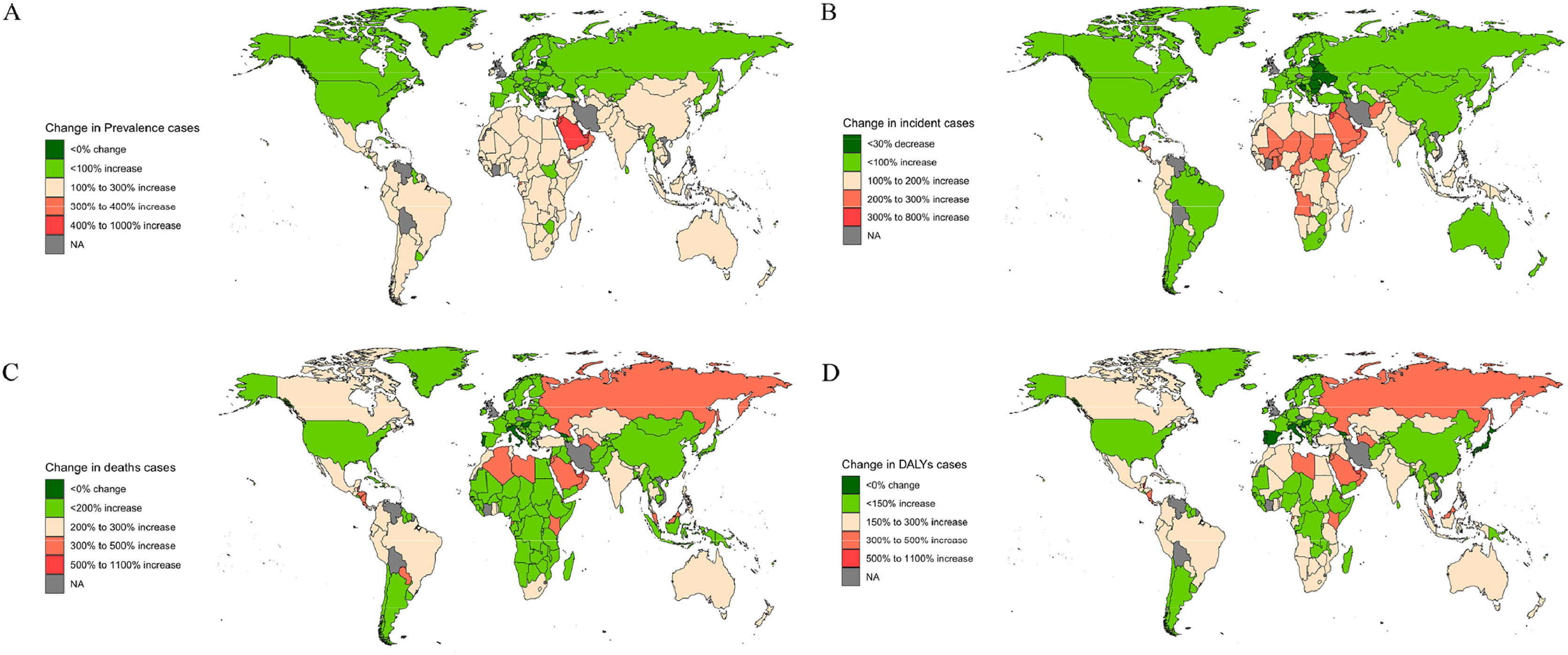

3.4National trendsIn 2021, China and India had the highest prevalence and incidence numbers for MASLD, with China reporting 291,261,235 (265,171,316–317,846,444) cases and 9572,435 (8788,951–10,377,517) incidence cases. Egypt and Kuwait had the highest ASPR and ASIR, with Kuwait having the highest ASPR at 32,312.17 (29,947.12–34,838.97) and Egypt the highest ASIR at 1188.57 (1107.18–1268.67). The ASPR was above the global level in 98 countries, and the ASIR was higher in 95 countries. From 1990 to 2021, Italy saw the largest growth in ASPR; From 1990 to 2021, Italy's ASPR grows fastest with the largest EAPC; Equatorial Guinea's ASIR has the largest EAPC; Cambodia's ASPR grows slowest with the smallest EAPC; and the Democratic Republic of the Congo's ASIR has the smallest EAPC. Cambodia has the smallest EAPC for the slowest growth in ASPR and Democratic Republic of the Congo has the smallest EAPC for ASIR (Fig. 4A,4B;Fig. 5A,5B; Supplementary Figure 2A, 2B; Supplementary Figure 3A, 3B).

In 2021, China, India, and Mexico had the highest numbers of MASLD deaths and DALYs. China had the most deaths at 16,748 (12,855–21,108), while India had the most DALYs at 439,776 (317,201–596,648). Egypt, Mexico, and Mongolia had the highest ASMR and ASDR, with Egypt having the highest ASMR at 9.44 (6.47–13.19) and Mexico the highest ASDR at 201.86 (149.30–265.64). The ASMR exceeded the global level in 127 countries, and the ASDR was higher in 132 countries. From 1990 to 2021, Russian Federation and Lithuania have the fastest growing ASMR and ASDR, corresponding to the largest EAPC, while Italy and South Korea have the largest declining ASMR and ASDR, corresponding to the smallest EAPC (Fig. 4C,4D;Fig. 5C,5D; Supplementary Figure 2C, 2D; Supplementary Figure 3C, 3D).

3.5Risk factorsIn 2021, the main risk factors for MASLD deaths were metabolic (high fasting plasma glucose [HFPG]) and behavioral (tobacco use [smoking]). Globally, the ASMR for MASLD deaths due to HFPG was 0.12 (0.01–0.23), and due to tobacco use was 0.04 (0.01–0.07). Among SDI regions, the Low SDI region had the highest ASMR for MASLD deaths due to HFPG at 0.15 (0.01–0.31), while the Middle SDI region had the highest ASMR for deaths due to tobacco use at 0.05 (0.01–0.08). Regionally, Southern Sub-Saharan Africa had the highest ASMR for MASLD deaths due to both HFPG (0.31 [0.03–0.63]) and tobacco use (0.07 [0.02–0.13]) (Supplementary Figure 4).

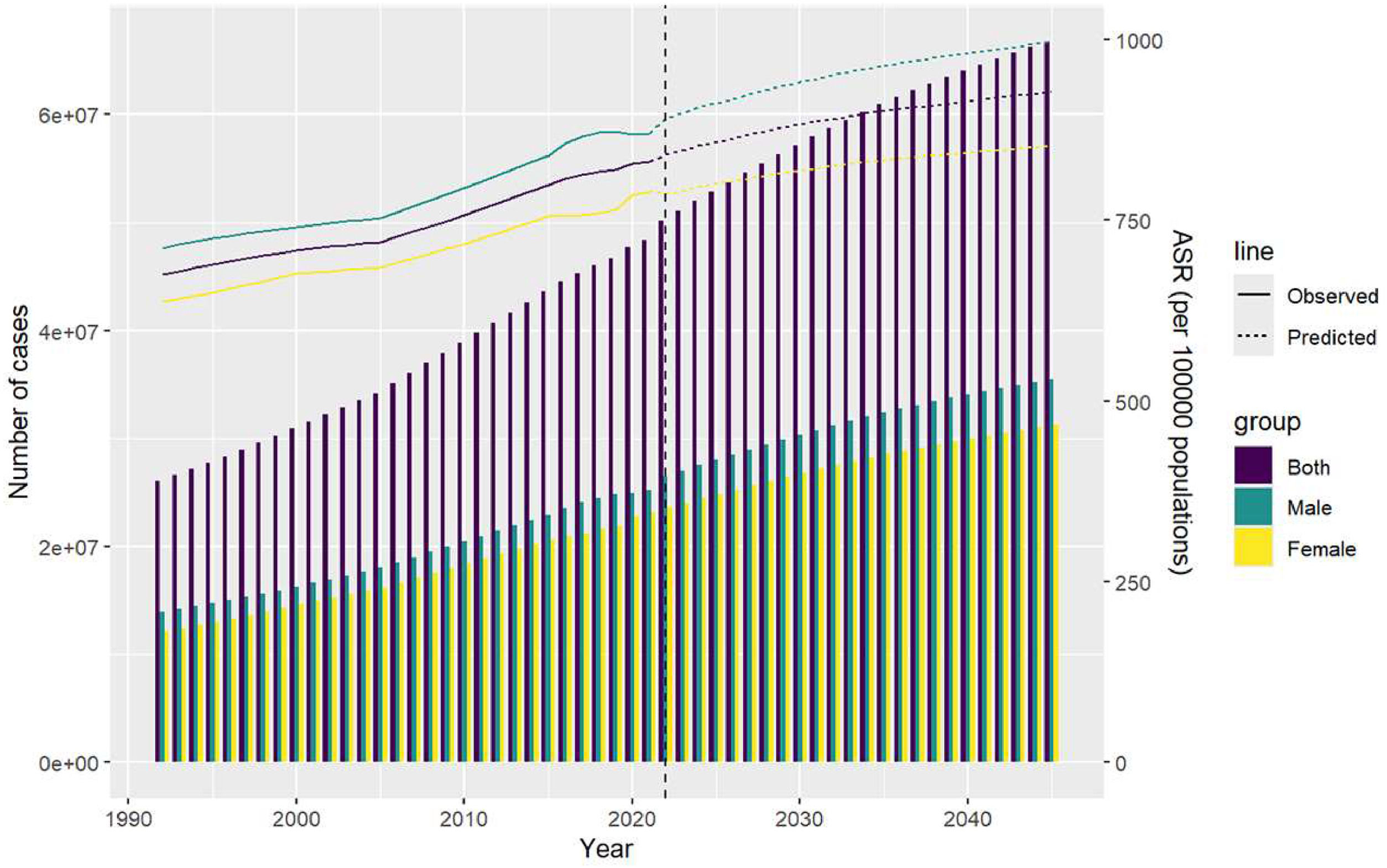

3.6Projections from 2020 to 2045The ASIR is projected to be 928.1023 per 100,000 people by 2045 due to the high number of people with MASLD, with an incidence of 667,577,740 (males: 355,126,664; females: 312,451,076). This is much higher than the global ASIR of 997.5815 for males and slightly lower than the global level of 853.3223 for females (Fig. 6).

4DiscussionThis study comprehensively analyzed the global burden of MASLD from 1990 to 2021 and provided projections for 2045. The results show a notable rise in global MASLD cases and incidence over the past three decades. This trend is concerning due to the high incidence and mortality rates, emphasizing substantial associated healthcare costs. Projected data from 2022 to 2045 indicate increasing global ASIR for these diseases. Our novel analysis offers valuable insights into the epidemiological trends of MASLD and underscores the urgency for targeted public health interventions.

MASLD has become the leading cause of chronic liver disease, and its increasing prevalence and incidence are closely linked to the rise in metabolic diseases worldwide. Our results align with studies documenting the parallel rise of MASLD and related metabolic disorders, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, especially in regions undergoing rapid changes in diet and lifestyle [25,26]. The data suggest that increasing prevalence of MASLD is closely linked to rising metabolic and lifestyle factors, such as sedentary behavior and the consumption of high-calorie diets, which are fueling the global rise in metabolic diseases [27,28]. In 2021, MASLD was responsible for 138,328 deaths and 3.67 million DALYs. Although ASMR and ASDR peaked in the early 1990s, both have declined since 2016. This decline can be attributed to several key factors, including advances in disease management, public health interventions, and medical progress. Enhanced early detection, along with comprehensive care strategies and health promotion campaigns advocating for healthier lifestyles, has substantially improved patient outcomes [29]. Moreover, innovations in diagnostics have allowed for more timely and accurate identification of MASLD, leading to earlier interventions. Additionally, the use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, originally developed for diabetes, has shown promise in treating MASLD by improving metabolic control and reducing liver fat and inflammation [30,31].

Geographic trends in MASLD reflect a complex interplay of socioeconomic, environmental, and healthcare factors [32]. In regions such as East Asia, South Asia, and North Africa, high prevalence and incidence are driven by large populations, inadequate healthcare, and socioeconomic disparities. In these areas, fragmented healthcare systems exacerbate the burden of MASLD, resulting in high ASIR and ASMR. Conversely, in Western Europe, where healthcare infrastructure is more advanced, the rise in ASIR and ASMR can be attributed to better detection and reporting, as well as an aging population. This highlights the critical role of healthcare systems in disease management. In contrast, the disparity between high-income Asia Pacific countries and low-income Sub-Saharan Africa emphasizes how economic development and healthcare access influence health outcomes. Low-income regions face challenges such as inadequate healthcare access, leading to higher MASLD-related morbidity and mortality, while high-income regions benefit from better healthcare infrastructure.

The socioeconomic and healthcare disparities strongly influence MASLD outcomes [15,33]. In regions with lower SDI, the burden of MASLD is exacerbated by limited access to primary care, lower screening rates, and delayed diagnoses, leading to higher mortality and DALYs. Factors such as poverty, food insecurity, and limited health literacy exacerbate the reliance on calorie-dense, nutrient-poor diets, which increase the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes [34,35]. Conversely, high-SDI regions often benefit from comprehensive screening programs, public health awareness campaigns, and broader access to healthcare. However, even in high-income countries, the rise in MASLD trends suggests that healthcare alone cannot resolve the issue; targeted interventions to address dietary and lifestyle risk factors are essential.

Gender differences also play a role in MASLD prevalence and outcomes. Our analysis revealed that men typically exhibit higher incidence rates over time, whereas, in certain regions, female mortality has surpassed male mortality in recent years. This shift can be attributed to distinct biological, behavioral, and socioeconomic factors. Men are more prone to visceral fat accumulation, a key driver of insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction, which increases their risk of MASLD [36,37]. In women, particularly postmenopausal, hormonal changes contribute to liver fat accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis, making them more vulnerable to severe MASLD outcomes [38,39]. Behavioral factors also influence these trends: men are more likely to engage in behaviors such as excessive alcohol consumption and smoking, which exacerbate disease progression. In contrast, women often experience diagnostic delays and face socioeconomic barriers to healthcare access, contributing to higher mortality rates in some regions. These gender-specific risks underscore the need for targeted prevention and management strategies to address these disparities effectively [40].

Our analysis identifies modifiable risk factors, particularly HFPG, tobacco use, and high alcohol intake, as key contributors to MASLD-related mortality. HFPG exacerbates insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction, leading to more severe liver damage over time [41]. Tobacco use promotes oxidative stress and inflammation in the liver, while excessive alcohol consumption causes direct hepatic injury and steatosis, compounding the metabolic burdens associated with MASLD. These findings align with previous research linking MASLD to metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and lifestyle factors such as smoking and excessive alcohol consumption [42,43]. Notably, the interplay among these risk factors differs by region, underscoring the importance of targeted intervention strategies: tobacco use poses a significant threat in Middle-SDI regions, while HFPG-related mortality is more prevalent in Low-SDI areas due to limited healthcare access and inadequate diabetes management [44]. In High- and Middle-SDI countries, despite broader healthcare coverage, hyperglycemia is rising due to sedentary lifestyles and high-calorie diets [45]. Mitigation strategies should focus on lifestyle modifications through a healthier diet, increased physical activity, and rigorous glucose management [46,47]. In Low-SDI regions, improved access to primary care and affordable diabetes treatments can help reduce HFPG-driven MASLD, while in Middle-SDI areas, bolstering tobacco control policies and smoking cessation programs could substantially lessen disease burden. Policy initiatives such as regulating sugar-sweetened beverages and enforcing stricter alcohol marketing controls can create healthier environments. Smoking cessation programs and public awareness campaigns are vital in high-risk areas [48]. Government initiatives to enhance nutrition and primary care access can address metabolic dysfunction early, reducing the global MASLD burden. Such region-specific approaches, tailored to the dominant risk factors, can more effectively curb the rising MASLD trends worldwide.

Projected data from 2022 to 2045 show a continuous rise in MASLD incidence. The ASIR for males exceeds the global average, indicating a disproportionate burden, while the ASIR for females, though slightly lower than the global level, remains concerning. These projections emphasize the critical need for effective public health strategies to address the growing prevalence of MASLD. Comprehensive efforts in prevention, early detection, and management are particularly vital in high-burden regions. Advancing research and implementing targeted interventions will be essential to mitigate this trend. Additionally, telemedicine, coupled with improved healthcare access and better socioeconomic conditions, has demonstrated potential in reducing mortality rates by enhancing care accessibility and facilitating timely intervention.

This study has several limitations. While the GBD dataset provides valuable insights, its quality varies across regions, and the lack of comprehensive healthcare reporting in low-income settings may lead to an underestimation of MASLD cases and mortality. Additionally, reliance on secondary data sources, such as hospital records, surveys, and national health databases, may introduce reporting biases, particularly due to the underdiagnosis and misclassification of MASLD as other chronic liver diseases. The projection models used in this study are based on historical data and assumptions that may not fully account for future changes in risk factors or advancements in treatment. Furthermore, recent FDA approvals of treatments, such as resmetirom for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, and other anticipated medical advancements could significantly alter the trajectory of MASLD [49]. As new treatments and policy changes reshape disease outcomes, projections based solely on current data may quickly become outdated. The study also lacks individual-level data and does not account for detailed regional variations in risk factors. Despite these limitations, the findings emphasize the urgent need for targeted public health interventions to address the growing burden of MASLD.

5ConclusionsThe global burden of MASLD has surged from 1990 to 2021, with projections indicating a continued rise through 2045. This increase, driven by metabolic and lifestyle factors presents a significant public health challenge. Data reveal that males face a more severe burden of MASLD, with regional variations influenced by socioeconomic and healthcare factors. The rising burden demands urgent public health interventions for prevention, early detection, and improved management. Policymakers must prioritize lifestyle changes, comprehensive screening, and enhanced clinical guidelines to mitigate this growing epidemic.

Data sharingThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) at http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2021.

FundingThis study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170865, 82370856), Taishan Scholars Project of Shandong Province (tsqn202211365). Research was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

None.