Pruritus is a common symptom in liver diseases, especially cholestatic disorders [1,2]. The frequency and severity of pruritus vary according to the underlying cause of cholestasis. The most common diseases associated with severe pruritus in children are Alagille syndrome, progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC), biliary atresia and sclerosing cholangitis [1]. Cholestatic pruritus can dramatically reduce quality of life in children, being cause of severe sleep deprivation and depressive mood [2]. It can be disabling to such an extent that liver transplantation can be an option even in the absence of end-stage liver disease [1,3] .

Effective management of pruritus requires an objective assessment of its intensity, which is crucial for evaluating treatment efficacy [4]. However, there is no established consensus on the management of cholestatic pruritus in children [5]. Standard medical therapy for cholestatic pruritus in intrahepatic cholestatic disorders—including ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), cholestyramine, rifampicin, and, less commonly, agents such as naltrexone or sertraline—often provides limited efficacy, particularly in patients with moderate to severe pruritus. While these treatments are widely used, their effectiveness and tolerability in pediatric populations remain inconsistent and are insufficiently supported by robust clinical data [2,6–9].

In pediatric patients with conditions such as Alagille syndrome and progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC), pruritus is frequently refractory to these interventions and remains a leading cause of liver transplantation. For instance, in Alagille syndrome, approximately 55 % of patients require liver transplantation before adulthood, and in 75 % of these cases, intractable pruritus is one of the main indications[10]. Similarly, among patients with PFIC, especially those with bile salt export pump (BSEP) deficiency, only about 30 % survive with their native liver into adulthood [11], with progressive cholestasis and uncontrolled pruritus being key drivers for transplantation. This underscores the urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies in this vulnerable population.

More recently, Ileal Bile Acid Transporter inhibitors (IBATi) have been introduced to address cholestatic pruritus in patients with Alagille syndrome and Progressive Familiar Intrahepatic Cholestasis (PFIC) [12–16]. These drugs show potential in pruritus control and may modify disease progression, but are only approved for two conditions in Europe [17]. Moreover, the high cost of these medications has also led to limitations in their availability in certain countries.

Fibrates (bezafibrate and fenofibrate) have demonstrated antipruritic and anticholestatic properties with a favourable safety profile in adult patients with fibrosing cholangiopathies [18–20]. While bezafibrate is a pan-PPAR agonist, activating PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ [18], fenofibrate is a selective PPARα agonist, exerting its effects mainly through this isoform, which plays a central role in lipid metabolism and bile acid homeostasis [21]. Although its use for dyslipidaemia is well-established [22], and it presents a good safety profile, even as an adjuvant treatment in neonatal hyperbilirubinemia [21,23], experience in treating pruritus in children is anecdotic [24].

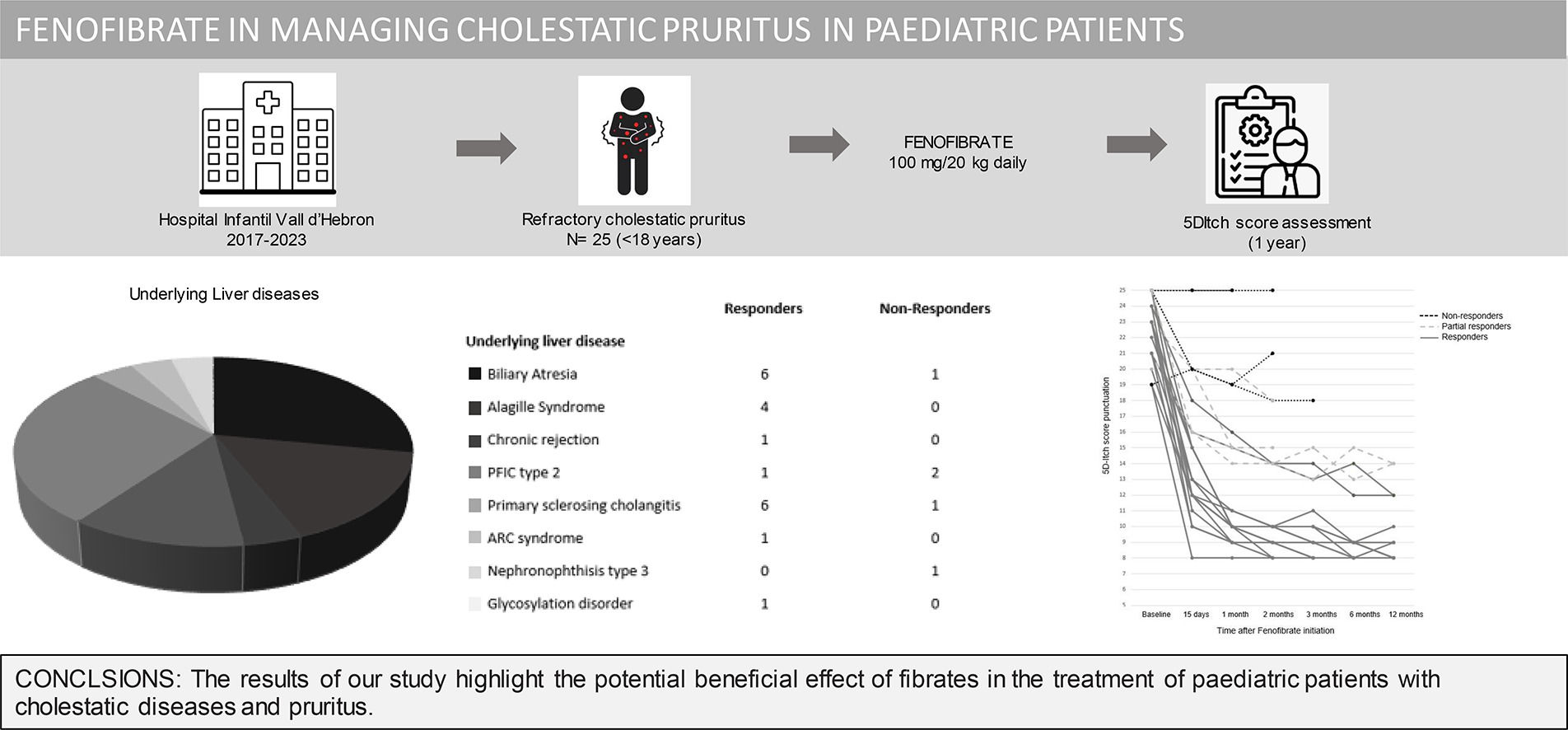

The aim of this study was to report the results of the application of a new protocol of fenofibrate use in refractory cholestatic pruritus in paediatric patients.

2Materials and methodsThis single center, retrospective study gathered data on a new treatment protocol using fenofibrate for pediatric patients with refractory cholestatic pruritus. Individuals under 18 years of age with moderate to severe pruritus unresponsive to standard medical therapy and diagnosed with fibrosing cholangiopathies were eligible for inclusion. Patients with obstructive cholestasis requiring invasive intervention (e.g., endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, or surgery) were excluded.

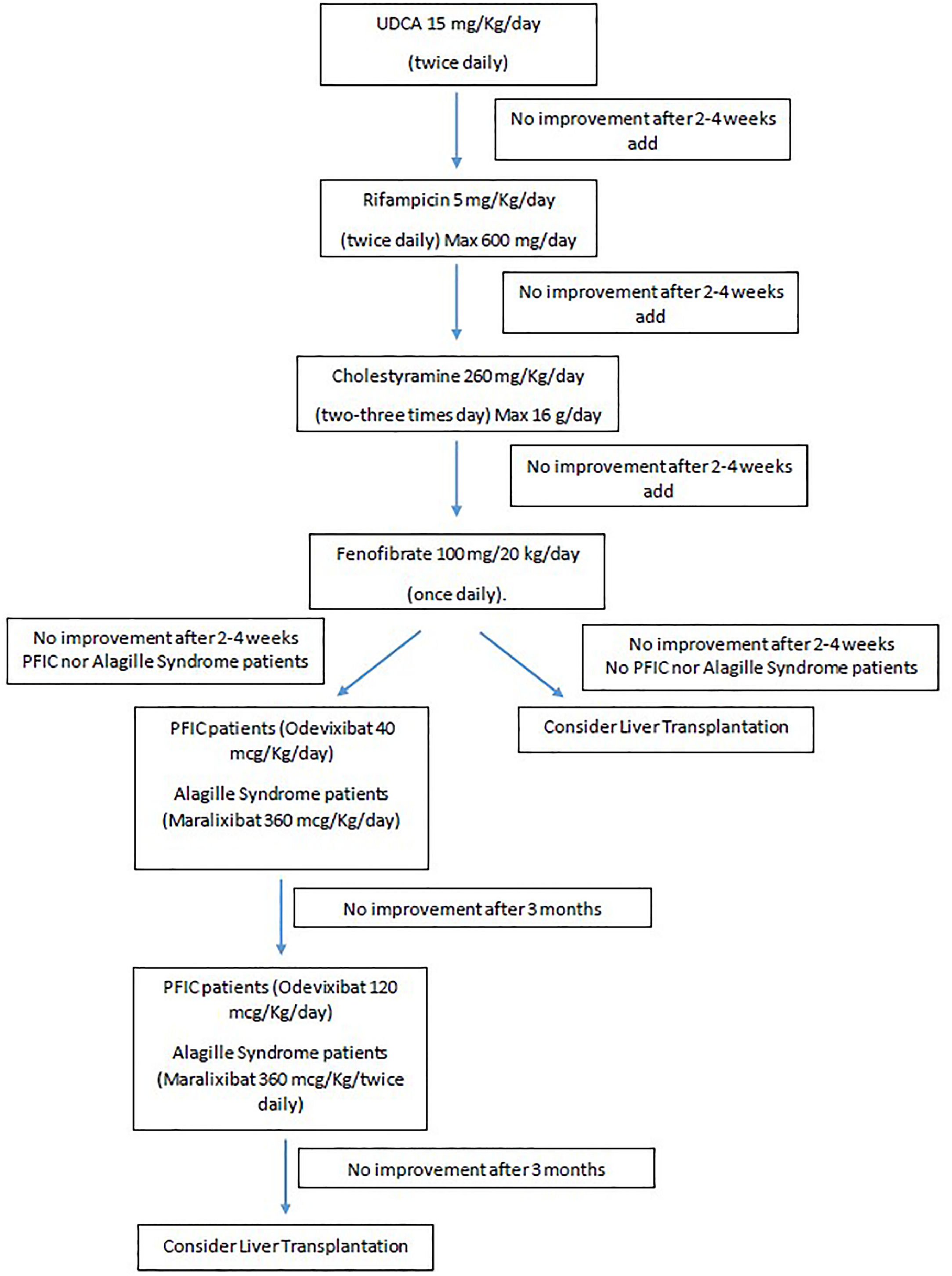

As depicted in Fig. 1, all patients underwent a stepwise introduction of conventional antipruritic therapy. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) was started first, followed by rifampicin and then cholestyramine, with each drug introduced sequentially at intervals of 2 to 4 weeks. Only patients who, after at least 2–4 weeks of combined therapy with all three agents, continued to experience significant pruritus (defined as a 5-D itch [25] score greater than 15), were considered refractory to conventional medical treatment and eligible to initiate fenofibrate therapy.

The recommended pediatric dose of fenofibrate is 100 mg per 20 kg of body weight once daily. For patients under 20 kg, a 10 mg/kg dose is given, with a maximum of 100 mg [21]. Fenofibrate is not used if the eGFR is <30 ml/min per 1.73 m². For eGFR between 30-59 ml/min per 1.73 m², the maximum dose is 100 mg daily. Based on the absence of specific dosing information in the product characteristics, the use of fenofibrate should be avoided in patients with an eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73 m² and weighing less than 20 kg. Exclusion criteria include signs of decompensated liver disease (e.g., ascites) or pruritus caused by non-cholestatic conditions (e.g., treatment-resistant atopic dermatitis). Additionally, patients presenting INR >2 or pretreatment ALT levels ≥5 times the upper limit of normal were also excluded.

2.2Assessment of efficacy2.2.1Pruritus evaluationThe treatment protocol includes five assessment points for pruritus using the 5-D Itch Scale at week two, and at one, three, six, and twelve months. The 5-D Itch Scale is a reliable, multidimensional measure of itch that has been validated in patients with chronic itch to effectively detect changes over time. The scale evaluates five key domains of itch: Duration, Degree, Direction (whether the itch is improving or worsening), Disability (impact on daily activities), and Distribution (location of the itch). Each domain is scored individually, and the total score is the sum of the five domains, ranging from 5 (no pruritus) to 25 (most severe pruritus) [24]. Participants aged 9 years or older completed the 5-D Itch Scale independently, with caregiver assistance for those aged 5 to 8 years. For children under the age of five, the scale was completed entirely by caregivers.

Patients were classified as fenofibrate responders if they achieved a >50 % reduction in the 5-D itch score. Partial responders showed a 25–50 % decrease, while non-responders had less than a 25 % reduction.

2.2.2Monitoring protocolBlood tests (blood count, liver and kidney function tests, bile acids and lipid profile) were conducted before treatment, at two weeks, and at one, three, six, and twelve months, with additional tests based on clinical needs. Ultrasound and Transient Elastography were performed prior to the initiation of fibrate therapy and again at the one-year mark.

2.3Safety assessmenteGFR was calculated using the Schwartz formula. If eGFR fell below 30 ml/min per 1.73 m², fenofibrate was discontinued. An increase in serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) greater than 5 times the upper limit of normal, or an increase greater than 3 times compared to baseline at the start of treatment, was considered the threshold to reduce the dose to half. If despite dose reduction, ALT was still > 5 times the upper limit of normal or >3 times compared with the start of the treatment, fenofibrate was stopped [19]. Treatment discontinuation criteria also included a two-fold increase in baseline total bilirubin or an international normalized ratio (INR) greater than 2 at any time.

2.4Statistical analysisContinuous variables were presented as median with range and categorical variables as number with percentage. Continuous variables were compared with the Mann–Whitney U-test. The median comparison for paired data was performed using the Wilcoxon test. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. To assess the correlation between the two variables, Spearman's rank correlation test was performed. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) version 18.0 was used for the analysis. The significance level was set at 0.05.

2.5Ethical statementThe study was approved by the local Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. As fenofibrate is not approved for the treatment of pruritus in children, parents were informed of its off-label use, which was documented in the medical records.

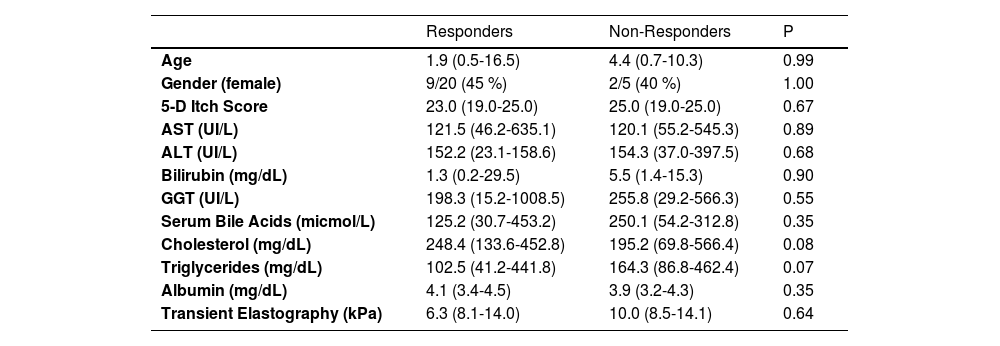

3ResultsTwenty-five patients were enrolled in the institutional off-label use protocol for fenofibrate in the treatment of refractory cholestatic pruritus between May 2017 and May 2023. The baseline characteristics of the patients are depicted in Table 1. Patients were under fenofibrate treatment a median of 24.2 months (range: 0.8–90.5 months). Five patients discontinued prematurely due to liver transplantation after a median of 2.6 months (range: 0.73–11.97 months). In all cases, transplantation was driven by refractory pruritus and pre-existing liver dysfunction, with no evidence of drug-induced hepatic deterioration. Importantly, none of the liver test abnormalities observed during treatment met the predefined criteria for drug discontinuation

Pre-treatment characteristics.

Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase (GGT).

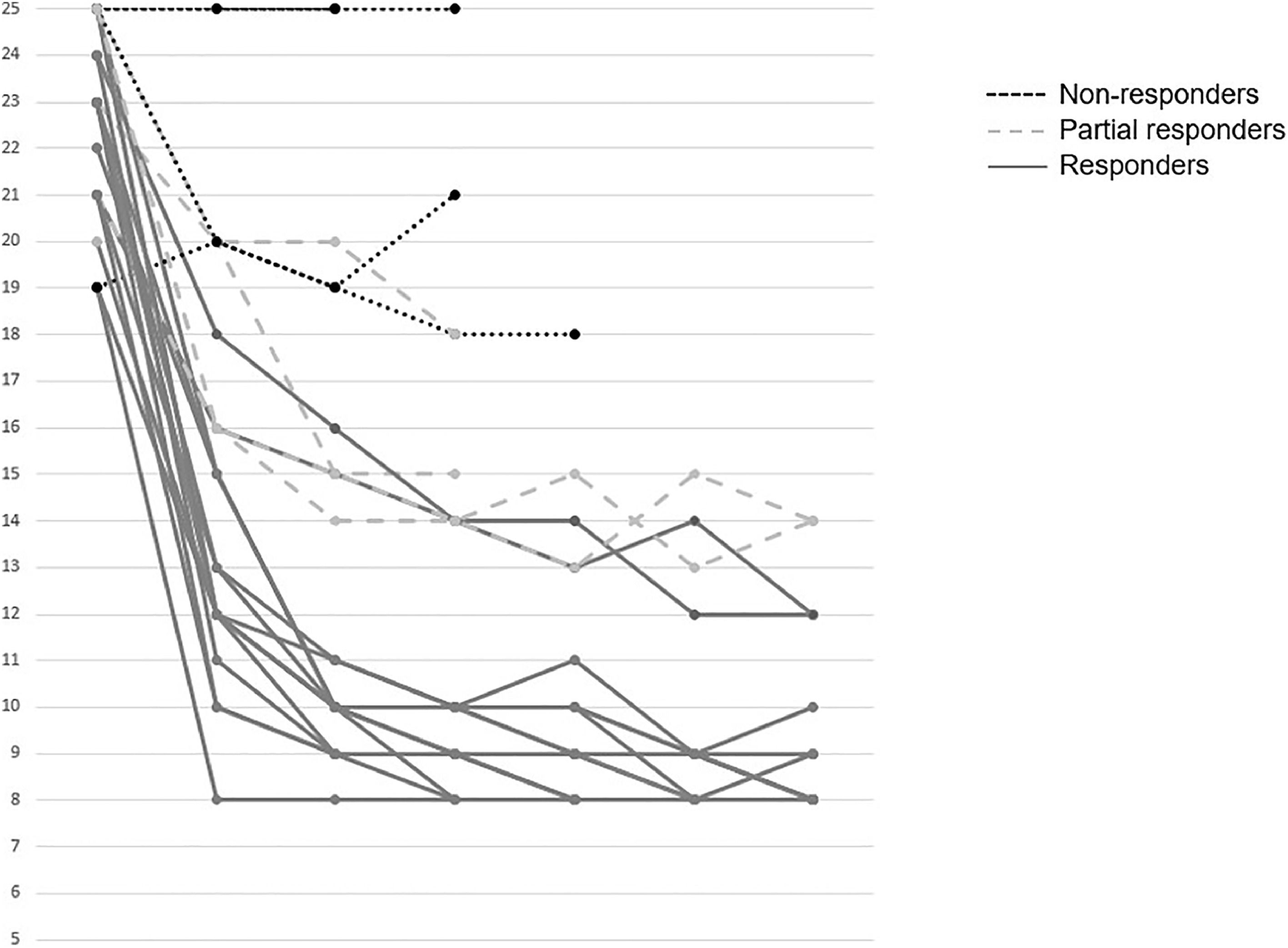

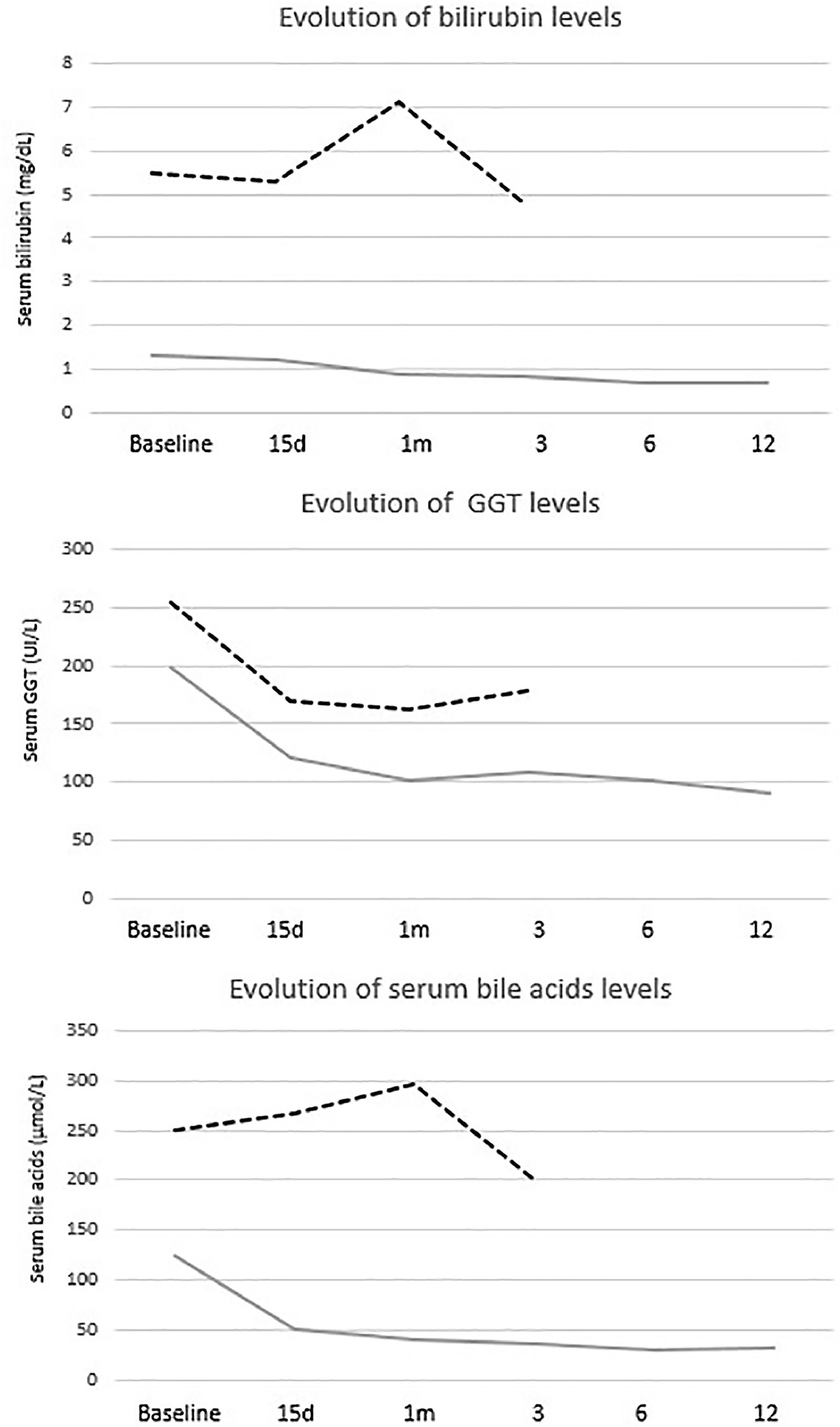

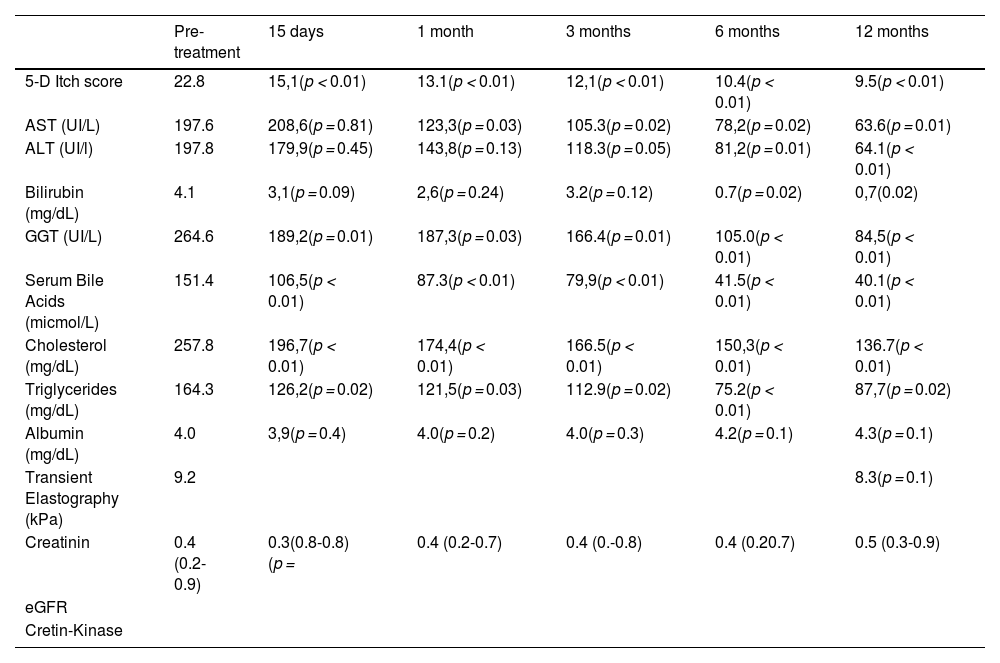

The mean reduction in pruritus was 36.8 %, 52.2 %, 53.6 %, 57.1 % and 60.8 % at week two, and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively. At one year, 64 % (16/25) of patients were full responders (>50 % reduction in the 5-D itch score), 16 % (4/25) were partial responders (25-50 % reduction in the 5-D itch score), and the remaining 20 % (5/25) were considered non-responders. Fig. 2 shows individual itch progression for responders, partial responders, and non-responders. There were no significant differences in the pre-treatment 5-D score between the responder groups (total and partial) and non-responders (Table 1). Although not statistically significant, baseline bilirubin levels tended to be higher in non-responders compared to responders, suggesting a potential association with more advanced disease. However, the levels of serum bile acids (sBA), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), ALT and albumin, and the fibrosis stage before the introduction of fenofibrate did not show statistically significant differences between responders (partial and total) and non-responders. Among the pre-treatment characteristics, the lipid profile showed a tendency to differ between responders and non-responders, with non-responders displaying higher cholesterol levels and lower triglyceride levels. (Table 1). The introduction of fenofibrate led to a significant reduction of sBA, AST, ALT, bilirubin, cholesterol and triglycerides level from the first month of treatment, but did not significantly affect elastography at 1 year (Table 2). Elastography data at 24 months of follow-up were available for 12 patients, showing a mean liver stiffness of 6.4 kPa (range 4.7–8.2), with a statistically significant reduction compared to baseline values (p = 0.02). Fig. 3 shows the evolution of cholestatic parameters over time according to response group. A moderate correlation could be established between the improvement in itching and the improvement in some cholestasis parameters (bilirubin and GGT) but neither for sBA nor for cholesterol (r = 0.41; p = 0.04, r = 0.51; p = 0.01 vs. r = 0.28; p = 0.18 and r=0.20; p=0.33, respectively).

Individual pruritus response after fenofibrate initiation. Evolution over time of the 5D Itch score for each patient following the introduction of fenofibrate treatment. Patients are categorized based on their response to treatment: Responders (≥50 % reduction from baseline score), Partial Responders (25-50 % improvement), and Non-Responders (<25 % improvement).

Post-treatment evolution.

Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alanine Aminotransferas (ALT), Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase (GGT).

Evolution of cholestatic parameters by response group. Responders showed numerically lower levels of cholestatic parameters (bilirubin, GGT, and serum bile acids) both at baseline and throughout follow-up. In contrast, non-responders presented consistently higher values, with no appreciable improvement during treatment. Data for non-responders are shown up to month 6, as fenofibrate was discontinued thereafter and no further follow-up was available.

No serious adverse events or deaths related to the use of the drug were reported. No patient had to discontinue treatment due to adverse effects. Four patients required a dose reduction due to elevated liver enzymes, which fully resolved at half the initial dosage. No worsening of renal function, rhabdomyolysis, or myalgia was reported.

4DiscussionThe results of our study suggest that fenofibrate may be a promising therapeutic option for patients with cholestatic pruritus due to fibrosing cholangiopathies. Among the 25 patients, 64 % demonstrated more than 50 % improvement from baseline. This reduction in pruritus was rapid and sustained for up to one year, with no improvement observed in non-responders after the first month. In our cohort, initial clinical and analytical assessments could not predict treatment response. The pruritus improvement may reflect improvement in cholestasis, suggesting a potential benefit of fenofibrate on both symptoms and liver function. While no significant correlation with liver fibrosis improvement was observed at 12 months, a significant correlation emerged at 24 months, possibly reflecting the longer time required for hepatic remodeling. While the differences did not reach statistical significance, non-responders tended to have higher baseline bilirubin levels. Numerically, other markers of cholestasis such as serum bile acids and GGT were also elevated in this subgroup. This pattern may reflect more advanced cholestatic disease at treatment initiation, which could partially explain the limited efficacy of fenofibrate observed in these patients. With a larger cohort, these trends might become statistically significant, supporting the hypothesis that greater disease severity is associated with poorer treatment response and warranting further investigation. The precise mechanisms underlying the anticholestatic effect of fenofibrate are still not fully elucidated. Fenofibrate is a selective agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα), with only weak activity on PPARδ and PPARγ. It is generally assumed that its primary mechanism of action in cholestasis involves the upregulation of multidrug resistance protein 3 (MDR3), a known PPARα target gene, leading to increased biliary phospholipid secretion and improved bile composition [26]. However, some studies in Primary Biliary Cholangitis patients suggested that the anticholestatic effects of fibrates might be attributed to mechanisms that do not rely on phospholipid secretion. In addition to these effects, alternative PPARα-mediated mechanisms such as the downregulation of key proteins involved in bile acid uptake and synthesis (e.g., NTCP, CYP7A1, and CYP27A1) may contribute to a reduction in hepatocellular bile acid accumulation, potentially alleviating pruritus and improving liver function [27]. Beyond bile acid synthesis and import, PPARα is also a strong regulator of bile acid detoxification via phase II conjugation processes [28] and export through basolateral transporters [29]. These combined actions could explain the clinical benefits observed in our cohort. However, due to the limited number of patients with available 24-month elastography data, it remains difficult to definitively conclude whether fibrates can alter the natural history of the disease, despite trends in liver stiffness and biochemical markers suggesting potential benefit. Larger, randomized studies in pediatric populations will be necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

As seen in studies with IBAT inhibitors [12–17], in patients with severely impaired bile acid homeostasis, the use of fibrates proves insufficient to control pruritus, and other therapeutic options, such as liver transplantation, may be indicated.

The doses used in this study correspond to those recommended in the fenofibrate technical datasheet for treating dyslipidemia. However, four patients experienced elevated liver enzymes after initiation of fenofibrate treatment and required dose reduction to 50 mg/20 kg daily, suggesting that starting fenofibrate at a lower dose might improve tolerability. Notably, these patients maintained their therapeutic response despite the dose reduction. An initial lower dosage with gradual escalation could be considered to minimize hepatic adverse effects while maintaining efficacy. Nevertheless, further prospective studies are needed to define the optimal dosing regimen that balances safety and therapeutic benefit.

We acknowledge that the reliance on patient-reported pruritus scales, such as the 5-D itch scale, represents a limitation due to its subjective nature. Future studies incorporating other clinician-assessed measures could provide a more comprehensive evaluation of treatment efficacy in pediatric cholestatic pruritus.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, the results of our study highlight the potential beneficial effect of fibrates in the treatment of paediatric patients with cholestatic diseases and pruritus. This opens the possibility of further evaluating their use through randomized clinical trials.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

None.

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.