Liver failure (LF) is a complex syndrome caused by various factors, leading to significant impairment of the liver’s synthetic, detoxification, metabolic, and biotransformation functions. It can progress to multi-organ failure and result in death[1,2]. The global prevalence and mortality rates of LF are high and have remained stable over time[3,4]. Specifically, the mortality rate for acute LF is 29%, while it can reach up to 48% for acute-on-chronic LF[5]. LF incurs substantial healthcare costs and poses a considerable burden on healthcare systems worldwide.[6,7].

Currently, primary treatments for LF include standard medical care (SMC), artificial liver support systems (ALSS), and liver transplantation[8–10]. The goal of managing LF patients is to maintain or restore vital organ functions while preventing multi-organ failure. In this regard, ALSS is valuable as it provides critical time for spontaneous liver regeneration or facilitates emergency transplantation[11–13]. However, being an invasive treatment, ALSS carries risks, with nosocomial infection being the most common and serious complication[14,15]. The incidence of nosocomial infections in ALSS can reach 40.0%, often leading to poor outcomes[16]. Nearly one-third of patients experienced electrolyte disturbances and renal impairment, resulting in prolonged hospitalization; 12% required intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Additionally, these infections may lead to multiple organ failures, reducing chances for transplantation and increasing mortality rates[17,18]. Therefore, evaluating the uncertain relationship between ALSS use and infections is crucial at this time. Although the efficacy of utilizing ALSS among LF patients has been extensively explored in previous studies, these randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were characterized by a limited number of LF cases and short-term follow-up periods[19]. This highlights the urgent need for longer follow-up periods among larger cohorts to adequately assess the impact of ALSS on the overall survival of LF patients.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the relationship between the utilization of ALSS and the incidence risk of nosocomial infections, as well as the associated mortality risk in patients with LF.

2Patients and Methods2.1Study designThis cohort study enrolled LF patients aged 18 years and older who received treatment at the Department of Gastroenterology, Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University, between June 2018 and August 2023. Comprehensive general and laboratory data were collected from all patients. This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the participating hospital (Approval Letter No. 2023-R493). All patients provided informed consent to participate in this study. Additionally, informed consent was obtained from the family members of the patients prior to the initiation of ALSS.

2.2Definition of LF patientsThe diagnostic criteria for LF were in accordance with the 2018 guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of LF[20]. Exclusion criteria included: (1) patients with incomplete primary clinical data; (2) individuals diagnosed with primary liver cancer or tumors located elsewhere; (3) patients with LF who presented infections upon admission or had pre-existing infections prior to undergoing ALSS treatment. Four patterns of LF patients (acute LF, sub-acute LF, acute-on-chronic LF, and chronic LF) were identified in this study based on the following diagnostic criteria[11]. Acute LF is characterized by rapid hepatic function decline within 2 weeks, evident bleeding tendency, plasma prothrombin activity ≤ 40% (or international normalized ratio [INR] ≥1.5), and hepatic encephalopathy in patients without prior liver failure. Sub-acute LF occurs with a relatively urgent onset (2–26 weeks), serum total bilirubin >10 times the upper limit of normal or an increase of 17.1 µmol/L per day, obvious bleeding tendency, and prothrombin activity ≤ 40% (or INR ≥ 1.5). Acute-on-chronic LF presents as short-term acute or sub-acute decompensated liver function on the background of chronic liver disease, with serum total bilirubin >10×ULN or increasing more than 17.1 µmol/L daily, bleeding tendency, prothrombin activity ≤40% (or INR ≥1.5), and decompensated cirrhosis with ascites. Chronic LF involves progressive deterioration and decompensation of liver function due to cirrhosis, marked increases in serum total bilirubin, significant decreases in albumin, evident bleeding tendency, prothrombin activity ≤ 40% (or INR ≥ 1.5), ascites, portal hypertension, or hepatic encephalopathy.

2.3Definition of SMC and ALSS groupsThe patients in the SMC group received only standard medical treatment, whereas those in the ALSS group were administered a combination of SMC and ALSS. The ALSS comprised several modalities, including plasma exchange, plasma diafiltration, hemodiafiltration, hemoperfusion, and the double plasma molecular adsorption system.

2.4Definition of primary and secondary outcomesNosocomial infection in LF patients is the primary outcome, defined as an infection occurring 48 hours after hospitalization[21]. This study identified six types of infections: pulmonary infection, urinary system infection, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, upper respiratory tract infection, acute biliary tract infection, and bloodstream infection. Pulmonary infection was defined by either a positive sputum culture or clinical manifestations such as fever, cough, sputum production, along with imaging changes. Chest imaging (chest X-ray or CT) revealed new or progressive infiltration/consolidation accompanied by one or more of the following clinical symptoms: fever, expectoration, cough, and dyspnea, and peripheral white blood cell count exceeding 10 ×10^9/L or falling below 4 ×10^9/L. Urinary system infections were diagnosed based on positive urine cultures; additional indicators included lower back pain and fever associated with upper urinary tract infections alongside renal percussion pain and increased urine white blood cells; they are alternatively characterized by frequent urination, urgency, and dysuria indicative of lower urinary tract infections also showing elevated urinary white blood cells. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis was diagnosed based on clinical signs consistent with peritonitis; ascitic neutrophil counts ≥25×10^6/L; exclusion of surgical secondary peritonitis; and either positive or negative ascitic fluid cultures. Upper respiratory tract infections are characterized as common viral infections affecting the nasal passages, pharynx, and upper airways, manifesting symptoms such as rhinorrhea (runny nose), nasal congestion, cough sneezing episodes sore throat, and headaches. Acute biliary tract infections primarily encompass acute cholecystitis and acute cholangitis, confirmed through symptomatology, inflammation, and imaging findings. Bloodstream infections include sepsis as well as catheter-related complications, where two infections are diagnosed via blood culture results combined with bone marrow analysis.

The secondary outcome of interest in this study was all-cause mortality. Dates of death were obtained either from officially issued death certificates or through interviews with close family members or village doctors when available. The duration of follow-up was defined as the interval between the date of the interview conducted in 2018 and the occurrence of outcomes, or until 2023. In instances where a participant missed a follow-up visit, their survival time was calculated as the period between their interview date in 2018 and the date of the missed visit.

2.5Definition of covariatesGeneral data included age, sex, length of hospital stays, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, drinking habits, history of disease (hypertension and diabetes), and etiology of LF. Laboratory data included C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, white blood cell count, neutrophil count, monocyte count, lymphocyte count, hemoglobin level, platelet count, INR, prothrombin activity and time, cholinesterase level, total bilirubin level, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, albumin level, creatinine level, sodium ion concentration, potassium ion concentration, and blood ammonia levels.

Age was divided into two groups: ≥50 and <50 years. Hospital stays were categorized as short or long based on the median duration of 16 days. BMI was classified as obesity (≥28.0 kg²/m) and non-obesity (<28.0 kg²/m). Smoking and drinking statuses were assessed by asking participants if they currently smoke or drink. A history of diseases was determined by the question, “Did you suffer from hypertension or diabetes?” A response of ‘yes’ was recorded as yes; otherwise, it was noted as no. The etiology of LF was categorized into virus-induced LF and other causes. Laboratory data were classified as abnormal or normal based on clinical cutoff values.

2.6Statistical analysisThe descriptive statistics of baseline characteristics were presented in accordance with the risk status for nosocomial infection and mortality. Continuous variables are reported as means accompanied by a 95% confidence interval (CI). Categorical variables were displayed as frequencies and percentages. One-way ANOVA was utilized to compare differences among continuous variables, while Chi-square tests were employed for categorical variables.

Logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs, as well as hazard ratios (HRs) with their 95% CIs. The backward stepwise regression method identified significant covariates for both univariable and multivariable analyses, which were included in the final models. We also conducted subgroup analyses and examined interaction effects, revealing an association between ALSS and mortality in LF patients based on demographic factors. Missing data in patients with less than 10% incomplete records were addressed using multiple imputation techniques. The significance level was set at α=0.05, with p<0.05 indicating statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using R software version 4.3.1, with statistical significance determined by a two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05.

3Results3.1Descriptive analysesIn this study, 421 LF patients aged ≥18 years were enrolled. Due to missing data, 115 patients were excluded from the analysis. Ultimately, our analysis included 306 LF patients with an average baseline age of 49.9 years (95% CI: 46.2-53.6); among them, there were 200 (65.4%) males and 106 (34.6%) females. A total of 131 patients with LF received a combination of SMC and ALSS treatment. The majority of these patients (97.7%) underwent either plasma exchange or a combination of plasma exchange and double plasma molecular adsorption. Additionally, a limited number of patients (2.29%) presenting with renal failure or hepatic encephalopathy were treated using plasma diafiltration. In contrast, there were 175 LF patients in the SMC group who received only standard medical treatment.

3.2Association of ALSS use and nosocomial infectionThe ALSS group reported 66 cases of nosocomial infections, while the SMC group documented 69 cases of nosocomial infections. No significant differences were observed between the two groups with respect to covariates, with the exception of hospital stays, C-reactive protein levels, neutrophil counts, hemoglobin levels, platelet counts, INR values, and cholinesterase levels. Table 1 presents the characteristics of study participants based on their infectious status during hospitalization.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 306 patients with LF, categorized by their infectious status during hospitalization.

LF, liver failure; BMI, body mass index; ALSS, Artificial Liver Support Systems.

The relationship between ALSS and the risk of nosocomial infection was assessed using logistic regression models adjusted for covariates (Table 2). Patients with LF in the ALSS group demonstrated a non-significant association with the risk of nosocomial infection (OR=1.189, 95% CI=0.442-3.202, p=0.732) when compared to those in SMC group. Similar associations were observed across other covariates; however, patients with LF who smoked and drank exhibited a significantly increased risk of nosocomial infection compared to non-smokers (OR=2.100, 95% CI=1.417-2.897, p=0.007) and non-drinkers (OR=1.567, 95% CI=1.021-2.778, p=0.012), respectively.

Univariate and multivariate analyses demonstrating the association between demographic factors, clinical characteristics, and nosocomial infection in patients with LF.

LF, liver failure; OR, odds ratio; CI: confidential interval; BMI, body mass index; ALSS, Artificial Liver Support Systems.

Over the entire follow-up period, we identified 150 deaths in the cohort: specifically, 55 deaths in the ALSS group and 95 in the SMC group were observed. Table 3 presents the characteristics of study participants according to follow-up outcomes.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 306 patients with LF, categorized by follow-up outcomes.

LF, liver failure; BMI, body mass index; ALSS, Artificial Liver Support Systems.

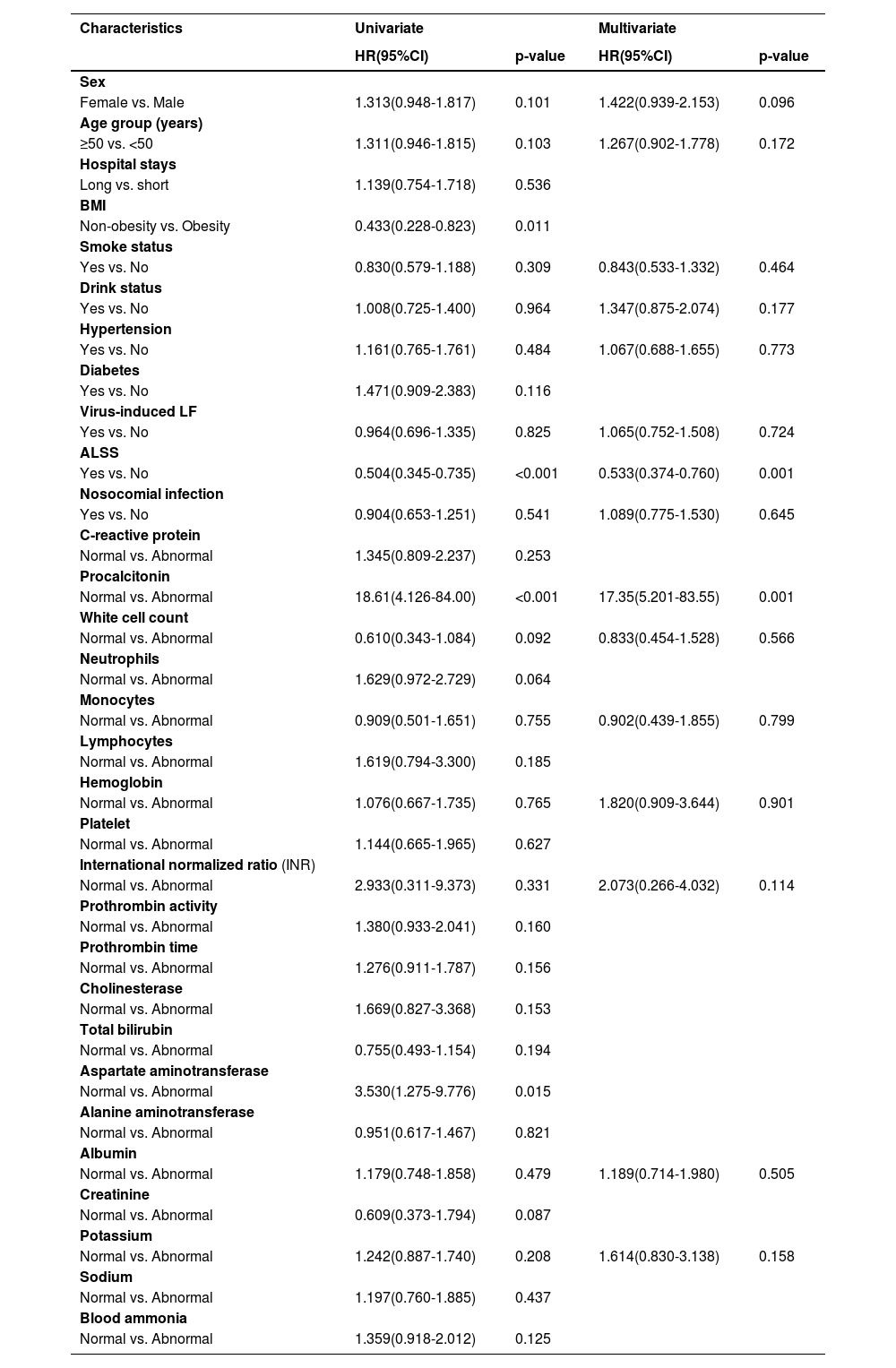

Table 4 presents the association between ALSS and the risk of mortality, which was assessed using Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for covariates. Patients with LF in the ALSS group illustrated a lower risk of mortality than that in patients in the SMC group (HR=0.533, 95% CI=0.374-0.760, p=0.001). The Kaplan-Meier analysis yielded comparable results, as illustrated in Fig. 1. However, nosocomial infection was not a significant risk factor for mortality (HR=1.089, 95% CI=0.775-1.530, p=0.645). In analyses of the procalcitonin test, we found that LF patients with high levels of procalcitonin had a higher risk of mortality than that in individuals with normal levels (HR=17.35, 95% CI=5.201-83.55, p<0.001).

Univariate and multivariate analyses demonstrating the association between demographic factors, clinical characteristics, and mortality in patients with LF.

LF, liver failure; HR, hazard ratio; CI: confidential interval; BMI, body mass index; ALSS, Artificial Liver Support Systems.

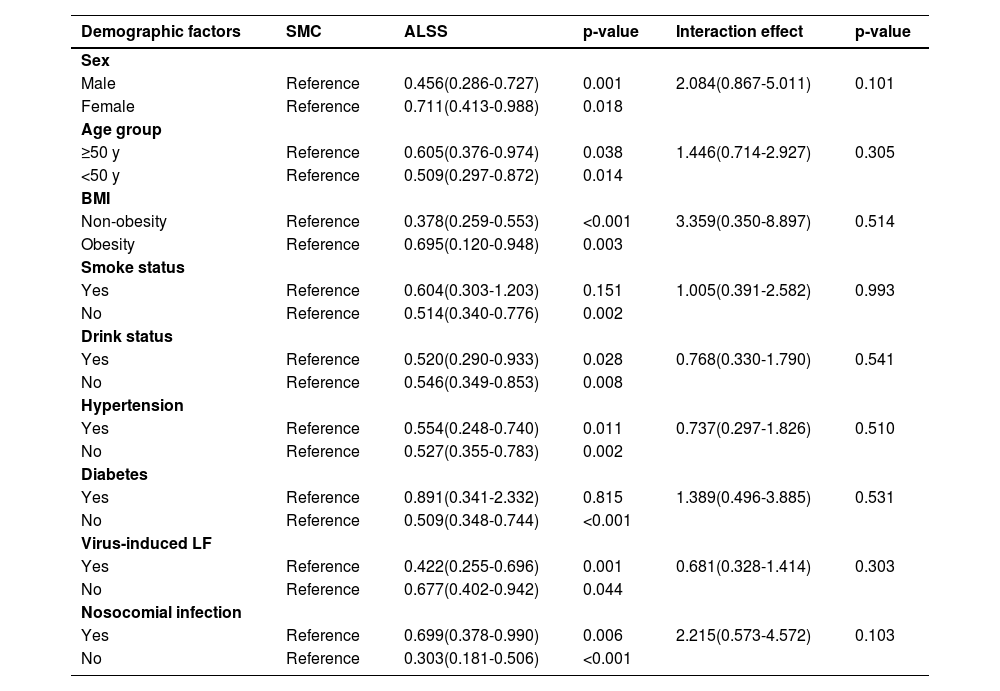

In the subgroup analyses, a significant relationship between ALSS and a lower risk of mortality was found in most subgroups. The interaction effect analyses of ALSS and demographic factors showed no significant association (Table 5).

Subgroup and interaction effect analyses demonstrating association between ALSS and mortality in patients with LF.

LF, liver failure; SMC, standard medical care; BMI, body mass index; ALSS, Artificial Liver Support Systems.

This study indicated that ALSS is not an independent risk factor for nosocomial infections. The application of ALSS has the potential to significantly extend the lifespan of patients with LF. Moreover, no interaction was observed between ALSS and nosocomial infection concerning the mortality rates of LF patients.

Although nosocomial infection is one of the most frequently discussed issues in the treatment of ALSS, most previous studies focusing on the epidemiology of nosocomial infections in patients with LF have identified disease severity, age, and underlying conditions, as well as total bilirubin and albumin levels as primary risk factors[22–24]. Elevated total bilirubin levels, transfusion of blood products, and a higher number of invasive procedures were independent risk factors for nosocomial infection in patients undergoing ALSS treatment[14]. However, our study found that the use of ALSS may not be an independent factor associated with nosocomial infections in LF patients. Furthermore, a recent large RCT meta-analysis demonstrated that extracorporeal liver support/ALSS was not significantly linked to nosocomial infections (RR=1.92; 95% CI=0.11-33.44)[19]. Therefore, reconsidering the relationship between the utilization of ALSS and nosocomial infections in patients with LF in future research is essential.

Additionally, we identified smoking as an independent risk factor for nosocomial infection among LF patients. Cigarette smoking predisposes individuals to pulmonary infection. Hospitalized patients with a history of smoking are more prone to developing hospital-acquired infections [25,26]. Our findings further corroborated this association by confirming smoking as a significant risk factor for nosocomial infection. This condition may be attributed to cigarette smoke, which induces the generation of an inflammatory phenotype in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). This alteration reduced their immunosuppressive properties and inhibited the capacity of MSCs to suppress inflammatory innate immune cells in the liver. Furthermore, it inhibited the production of inflammatory Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes, reducing the body's ability to fight infections. This led to an increased vulnerability to infections among individuals[27]. Our analyses also indicated that alcohol consumption is a significant contributor to the incidence of nosocomial infections[28]. Similar findings were noted in previous studies, where alcohol consumption was significantly associated with complications and adverse outcomes in LF patients[29,30]. Therefore, LF patients who engage in smoking and drinking habits should be monitored more closely due to their elevated risk of developing nosocomial infections.

The global prevalence and mortality rates associated with LF are notably high, while the accessibility of liver transplantation remains low for the majority of patients[31,32]. Extracorporeal liver support/ALSS has been recommended as an effective method for prolonging the lives of LF patients and serving as a bridge to liver transplantation[11]. The available evidence indicates that approximately 37% of patients listed for emergency liver transplantation demonstrate recovery following treatment with ALSS, while 50% unfortunately succumb while awaiting an organ[33]. A meta-analysis involving 25 RCTs, which included a total of 1,796 LF patients, reported that the use of extracorporeal liver support/ALSS was associated with a reduction in mortality (RR=0.84; 95%CI=0.74-0.96) among patients suffering from acute LF or acute-on-chronic LF[19]. Similar results were observed across all subgroups, except for those with smoking and diabetes-related LF. The toxic components of cigarette smoke enter the bloodstream through the lungs and affect various organs—including the lungs, liver, kidneys, heart, gut, blood vessels, and brain—thereby impairing their function[34]. Cigarette smoke induced oxidative stress and inflammation while triggering harmful immune responses in different tissues. It plays a significant role in the progression of bronchitis, emphysema, gastroenteritis, hepatitis, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; prolonged exposure to cigarette smoke notably increases the risk of lung, liver, and colon cancers, ultimately leading to mortality[35]. Available evidence suggests that diabetes may lead to adverse outcomes in LF patients[36]. Further studies on liver transplantation indicated that donor diabetes mellitus is associated with inferior outcomes following transplantation[37]. Therefore, it can be concluded that both cigarette smoke exposure and diabetes may diminish the protective effect of ALSS treatment in prolonging survival among patients with LF.

Notably, abnormal procalcitonin levels were identified as significant risk factors for mortality in patients with LF. Serum procalcitonin levels serve as reliable prognostic indicators for 30-day mortality and should be incorporated into clinical practice to stratify risk and facilitate early, effective treatment in acute-on-chronic LF patients[38]. LF patients exhibit elevated serum procalcitonin levels, irrespective of bacterial infections, with higher levels correlating with poorer prognoses[39]. These findings reinforce our conclusions from an alternative perspective. While procalcitonin was recognized as an early diagnostic marker for bacterial infection, it also serves as a precise indicator of mortality risk. You et al. indicate that procalcitonin is a moderately accurate diagnostic marker for post-operative infections in adult liver transplant recipients. A recent study conducted among Indian patients with ALF suggested that in those who underwent PE treatment, procalcitonin (HR=1.18, 95% CI=1.07-1.30) was identified as an independent predictor of mortality[40]. Furthermore, its diagnostic performance can be enhanced when combined with other inflammatory biomarkers [41]. Fan et al. reported that the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio could predict short-term mortality in acute-on-chronic LF patients undergoing treatment with ALSS[42]. Thus, procalcitonin may represent a valuable prognostic biomarker for individuals suffering from LF.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, as a retrospective study, the authenticity of the information is challenging to ensure, and recall bias is difficult to eliminate. Additionally, due to the opportunistic nature of its diagnostic and therapeutic approach, the study could only include patients who sought medical care at healthcare institutions. This limitation may introduce potential selection bias among participants and result in uneven baseline characteristics. Then, We are unable to fully capture certain clinical parameters in the historical medical records due to the retrospective design of this study. Consequently, important indicators of patient status, such as coma grade, MELD score, and Child-Pugh score, cannot be assessed. Nevertheless, we can indirectly evaluate the severity of the patient's condition. For example, INR, bilirubin levels, and creatinine are critical components used in calculating the MELD score. Furthermore, relevant parameters including bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time, and blood ammonia levels are available in our dataset and can provide insights into the status of hepatic encephalopathy to some extent. Lastly, the limited number of patients from a single center may also impact the findings of this research.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, ALSS is not an independent risk factor for nosocomial infections and can effectively prolong the lifespan of LF patients without liver transplantation. The application of ALSS provides a valuable therapeutic option, offering hope and improved prognosis for individuals with LF, offering them a greater chance of survival.

Author contributionsConceptualization: Yuan Li, Xiaoting Wang and Yan Wang; Data curation: Yuan Li, Xiaoting Wang, Junkai Fan, Jiale Xie and Chunrong Ping; Formal analysis: Yuan Li, Xiaoting Wang, Junkai Fan and Huimin Liu; Software: Yuan Li and Xiaoting Wang; Visualization: Yuan Li and Xiaoting Wang; Writing – original draft: Yuan Li, Xiaoting Wang and Yan Wang; Writing – review & editing: Yuan Li, Xiaoting Wang, Junkai Fan, Jiale Xie, Huimin Liu, Chunrong Ping, Zhijie Feng and Yan Wang. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processNo AI or AI-assisted technologies were used during the preparation of this work.

FundingThis work was supported by Key Science and Technology Research Program of Health Commission of Hebei Province (20200930 to Yan Wang).

None.