Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) refers to liver test abnormalities or hepatic dysfunction after exposure to prescription or over‐the‐counter medications, as well as herbal and dietary supplements [1]. DILI is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition and gradually becomes the main cause of acute liver failure worldwide [2]. The incidence of DILI is about 12.0∼23.8 per 100,000 people in the general population and can reach 1∼6 % among hospitalized patients [2–6]. In recent years, DILI has received increasing attention from the public and medical community, and multiple authoritative academic organizations have developed diagnosis and treatment guidelines to direct DILI clinical management [7–10]. However, due to the variety of potentially pathogenic drugs, complicated pathogenesis, and lack of specific diagnostic biomarkers and treatment methods, the clinical management of DILI is still challenging at present [11,12].

In clinical practice, timely identifying and discontinuing culprit-drugs is the main principle of DILI management [7–10], so it is necessary for medical personnel to understand the potential hepatotoxicity of drugs. Currently, there are more than 1000 drugs considered to have potential hepatotoxicity [13], among which antimicrobials, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and herbal and dietary supplements are generally reported as the most common culprit-drugs of DILI [14]. However, although some prospective and retrospective studies have provided detailed DILI incidence data of involved drugs [5,15], the exact DILI risk data of most drugs are still very limited [16]. In addition, with the development and application of new drugs in recent years, new therapies such as gene therapy and novel antineoplastic drugs have become an increasingly important trigger for DILI in the clinic [17,18]. Therefore, it is necessary to reconfirm the liver risk characteristics of drugs and provide updated reference information for clinical management of DILI.

Pharmacovigilance is defined as the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding, and prevention of adverse effects or any other possible drug-related problems [19]. Spontaneous reporting database, as an important pharmacovigilance data resource, can provide a direct perspective for understanding the potential toxicity risk of drugs [20]. In terms of exploring the hepatotoxicity of drugs, several previous studies have used the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database, the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report database, and the VigiBase database to summarize the liver safety profile of drugs, respectively [21–23]. However, the latest study only acquired and analyzed the data of liver injury reports before 2019 [23], which has made it difficult to reflect the current epidemic state of hepatotoxic drugs. Additionally, although the above-mentioned studies have comprehensively reviewed the liver injury reports in the target pharmacovigilance database, they only highlighted a limited number of the most frequently reported hepatotoxic drugs and the drugs with the strongest hepatotoxic risk signal [21–23]. Therefore, using spontaneous reporting databases to understand the hepatotoxicity risk of drugs is a feasible strategy, but a comprehensive landscape of hepatotoxicity associated with drugs is still lacking at present.

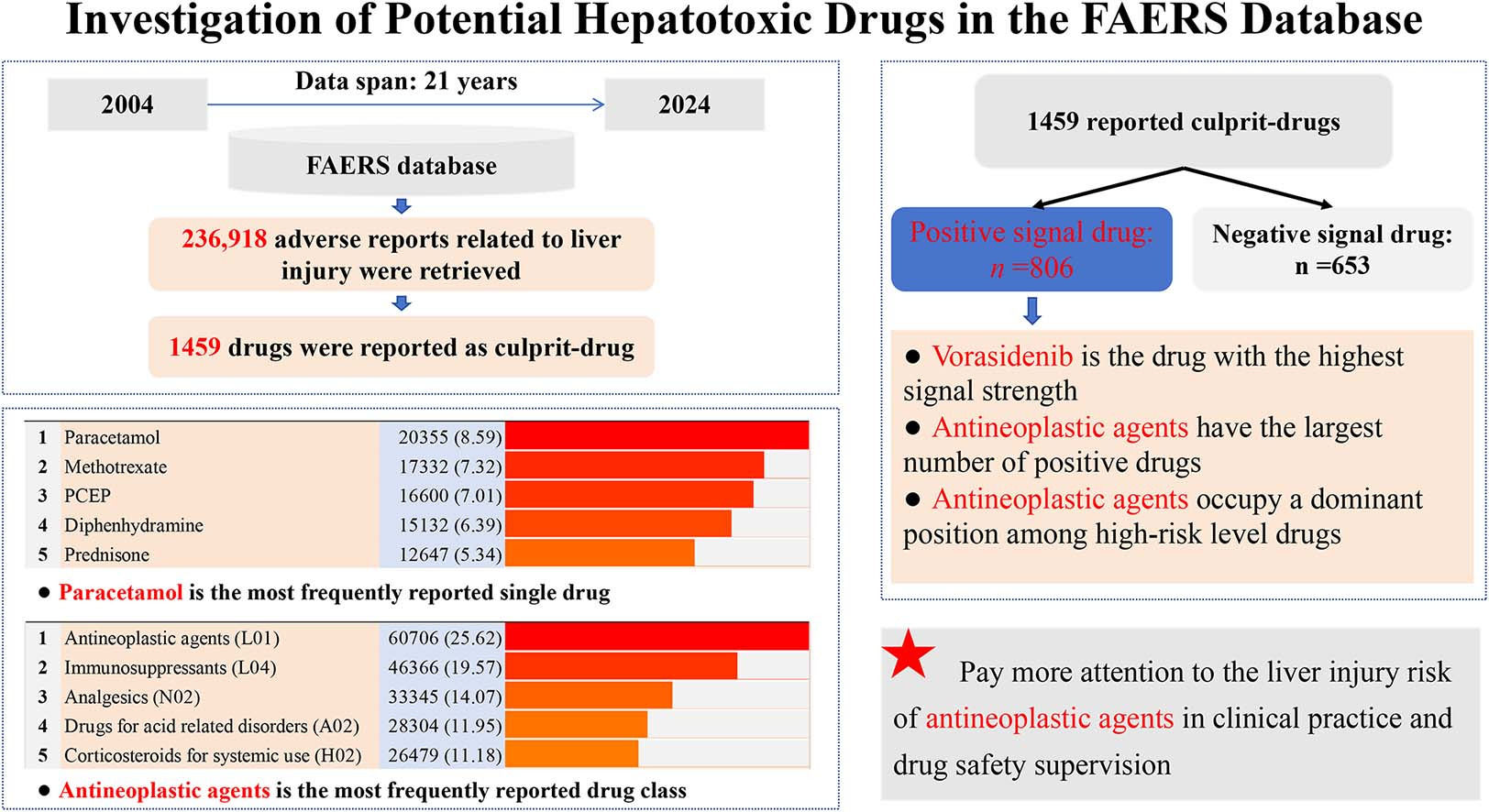

In this context, we investigated all the AE reports related to liver injury in the FAERS database from 2004 to 2024, compiled a comprehensive list of reported hepatotoxic drugs, and assessed the hepatotoxic risk of all reported drugs by disproportionality analysis, trying to provide updated and more comprehensive reference information for DILI clinical management from the perspective of pharmacovigilance.

2Materials and methods2.1Data sourceThe FAERS database is a post-marketing safety surveillance program run by the FDA, which contains post-marketing adverse event (AE) reports on drugs and therapeutic biologic products submitted by healthcare professionals, consumers, and manufacturers [24]. Currently, there are more than 19 million AE reports recorded in the FAERS database, and it maintains an annual increase of nearly 1.3 million. For each archived AE report, information such as reporting time, report sources (reporter and reporting country), patient demographic characteristics (sex and age), patient outcomes, drug information, and adverse reactions involved are recorded in a highly structured format. openFDA is an official project operated by the FDA that aims to index high-value, high-priority, and scalable public-access data, and AE data in the FAERS database is one of the indexed resources [25]. In this study, we used the application programming interface (API) provided by the openFDA platform to programmatically call and obtain report information related to liver injury.

2.2Identifying the target reportsIn the FAERS database, all the adverse reaction information involved was converted to standardized terminology called Preferred Term (PT) by using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA). Referring to MedDRA (version 27.0), we used drug-induced liver injury (code: 10,072,268), hepatocellular injury (code: 10,019,837), cholestatic liver injury (code: 10,067,969), mixed liver injury (code: 10,066,758), acute hepatic failure (code:10,000,804) and some other PTs that significantly indicate hepatic failure, fibrosis and cirrhosis and other liver damage-related conditions to identify and download target reports. The 90 PTs used in this study are detailed in Table S1.

2.3Integrating the reported etiological drugsIn order to get the potential causative drug list of DILI, we inquired and extracted the generic names of drugs recorded in the field of “patient.drug.openfda.generic_name” of each downloaded DILI report. After excluding non-primary suspected drugs, drugs with duplicated names, drugs missing generic names, and drugs with ambiguous semantics, an initial list of potential DILI-causative drugs was established. After that, the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system was used to code drugs in the initial list, and the synonymous drugs with the same ATC code (e.g., aspirin and acetylsalicylic acid) were integrated manually to obtain the final reported DILI-causative drug list.

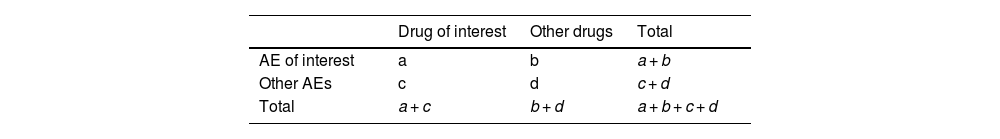

2.4DILI risk signal detectionDisproportionality analysis is a kind of technology used to detect risk signal of drugs by comparing the differences between the occurrence frequency and background frequency for target drugs and target AEs [26]. In this study, we used reporting odds ratio (ROR), a classic disproportionality analysis method, to evaluate potential DILI risk of drugs. Based on the two-by-two table (Table 1), the ROR value and corresponding 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) are calculated by using following formula:

For the detected signal result, a positive risk signal is defined as where there are at least three target cases (a in Table 1 ≥ 3) and the lower limit of the 95 %CI is greater than 1 [27].

2.5Distribution statistics of positive signalsFor drugs with positive DILI risk signals, there may also be significant differences in signal strength between drugs. Generally, high signal intensity (high ROR value) statistically indicates the potential high DILI risk [28]. In order to distinguish the DILI risk differences between positive drugs, we ranked the ROR values of positive signal drugs and divided positive signal drugs into four risk levels (levels A, B, C, and D) according to the top 5 %, 6 %–20 %, 21 %–50 %, and 51 %–100 % of ROR values respectively [29]. Meanwhile, based on the ATC drug classification system, we made statistics on the distribution of positive signal drugs in different drug categories.

2.6Ethics statementThis study analyzed publicly available, de-identified data from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) accessed via openFDA. No human subjects were involved and no intervention was performed; therefore, institutional review board/ethics approval and informed consent were not required. Data use complied with FAERS/openFDA terms and privacy safeguards.

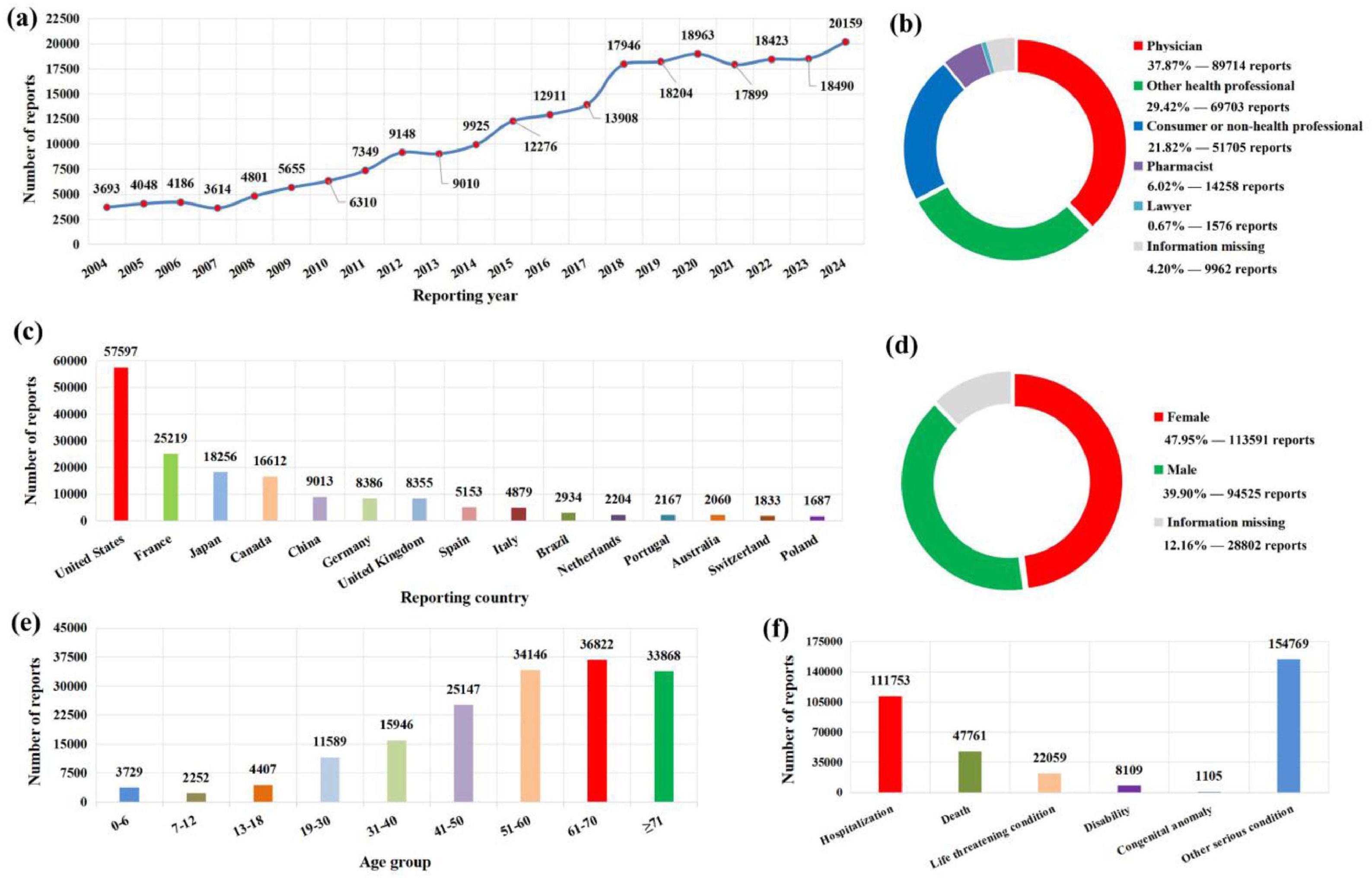

3Results3.1General characteristics of DILI reportsDuring the period from January 1, 2004, to December 31, 2024, a total of 236,918 target reports related to liver injury were submitted to the FAERS database. On the whole, the number of annual reports on DILI has increased year by year and reached its highest in 2024 (Fig. 1a). In terms of reporting source, physicians (37.87 %) accounts for the highest proportion of the reporters, and the United States (Fig. 1b), France, Japan, Canada, and China are the top five countries with the highest number of submitted reports (Fig. 1c). In terms of patients, female patients are significantly more than male patients (Fig. 1d), and the age of patients is mainly concentrated in the age group over 50 years old (Fig. 1e). With regard to patient outcomes, hospitalizations accounted for 47.17 % of cases, death accounted for 20.16 % of cases, and 65.33 % of patients had other serious conditions (Fig. 1f).

The basic information and patient characteristics of 236,918 DILI-related reports. (a) Distribution of annual report quantity; (b) The occupational distribution of the submitter; (c) The top 15 reporting countries; (d) The gender distribution of patients; (e) The age distribution of patients; (f) the outcome distribution of patients.

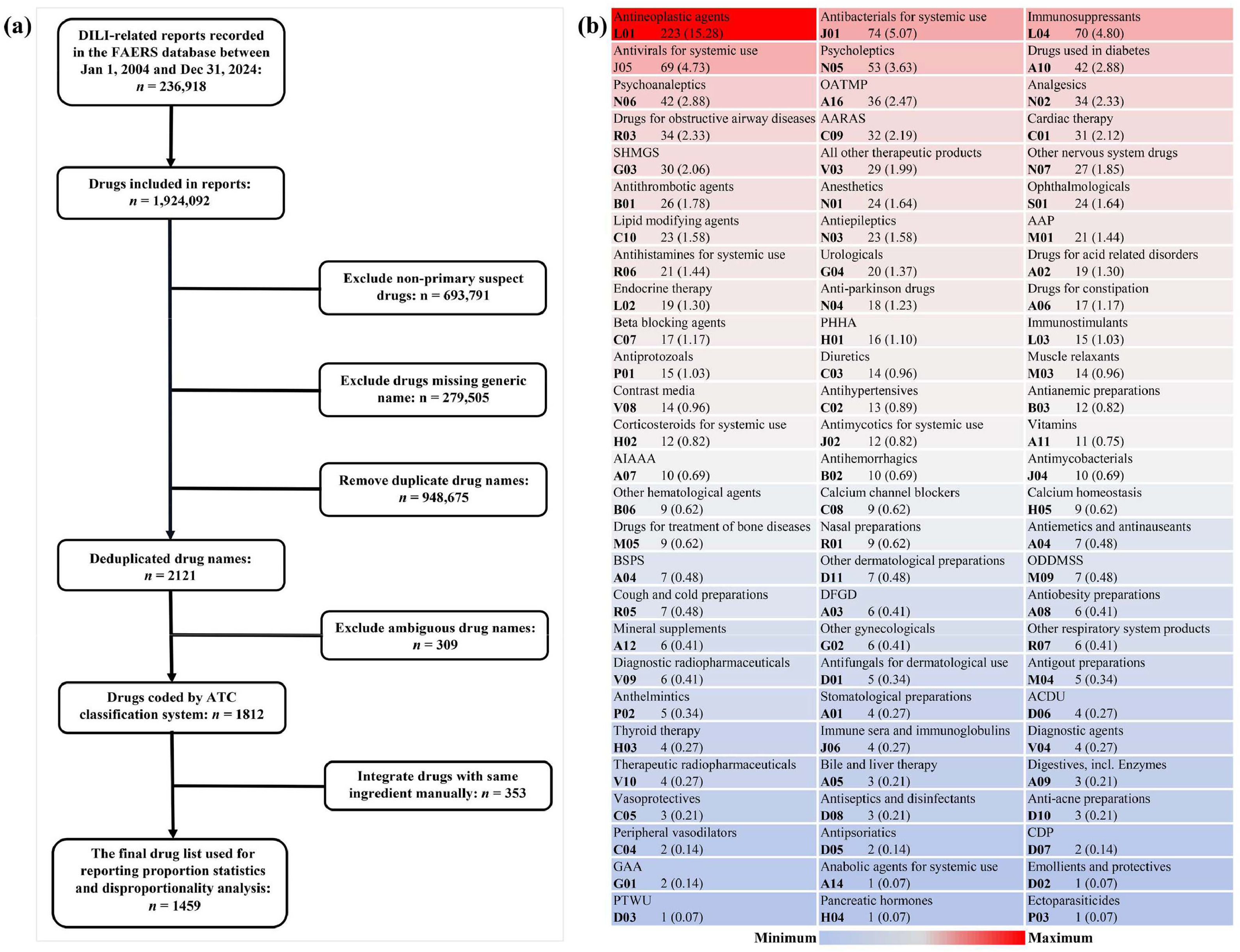

Due to an AE report usually involving multiple drug information records, 1924,092 drug information records were extracted from 236,918 downloaded DILI reports. After excluding non-primary suspected drugs, drugs with duplicated names, drugs missing generic names, and drugs with ambiguous semantics, the remaining drugs make up an initial list of 1812 reported causative drugs and were coded by the ATC classification system. Subsequently, drugs with the same ATC code were integrated manually, and a final list containing 1459 reported DILI culprit-drugs was obtained (Fig. 2a). Among them, the largest number of drugs were classified as antineoplastic agents (n = 223), followed by antibacterials for systemic use (n = 74), immunosuppressants (n = 70), antivirals for systemic use (n = 69), and psycholeptics (n = 53) (Fig. 2b).

Identification and classification of reported potential hepatotoxic drugs. (a) Flowchart of reported hepatotoxic drugs identification; (b) Classification and summary of reported hepatotoxic drugs. AAP, antiinflammatory and antirheumatic products; AARAS, agents acting on the renin-angiotensin system; ACDU, antibiotics and chemotherapeutics for dermatological use; AIAAA, antidiarrheals, intestinal antiinflammatory/antiinfective agents; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical; BSPS, blood substitutes and perfusion solutions; CDP, Corticosteroids in dermatological preparations; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; DFGD, drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders, GAA, gynecological antiinfectives and antiseptics; OATMP, other alimentary tract and metabolism products; ODDMSS, other drugs for disorders of the musculo-skeletal system; PHHA, pituitary and hypothalamic hormones and analogues; PTWU, preparations for treatment of wounds and ulcers; SHMGS, sex hormones and modulators of the genital system.

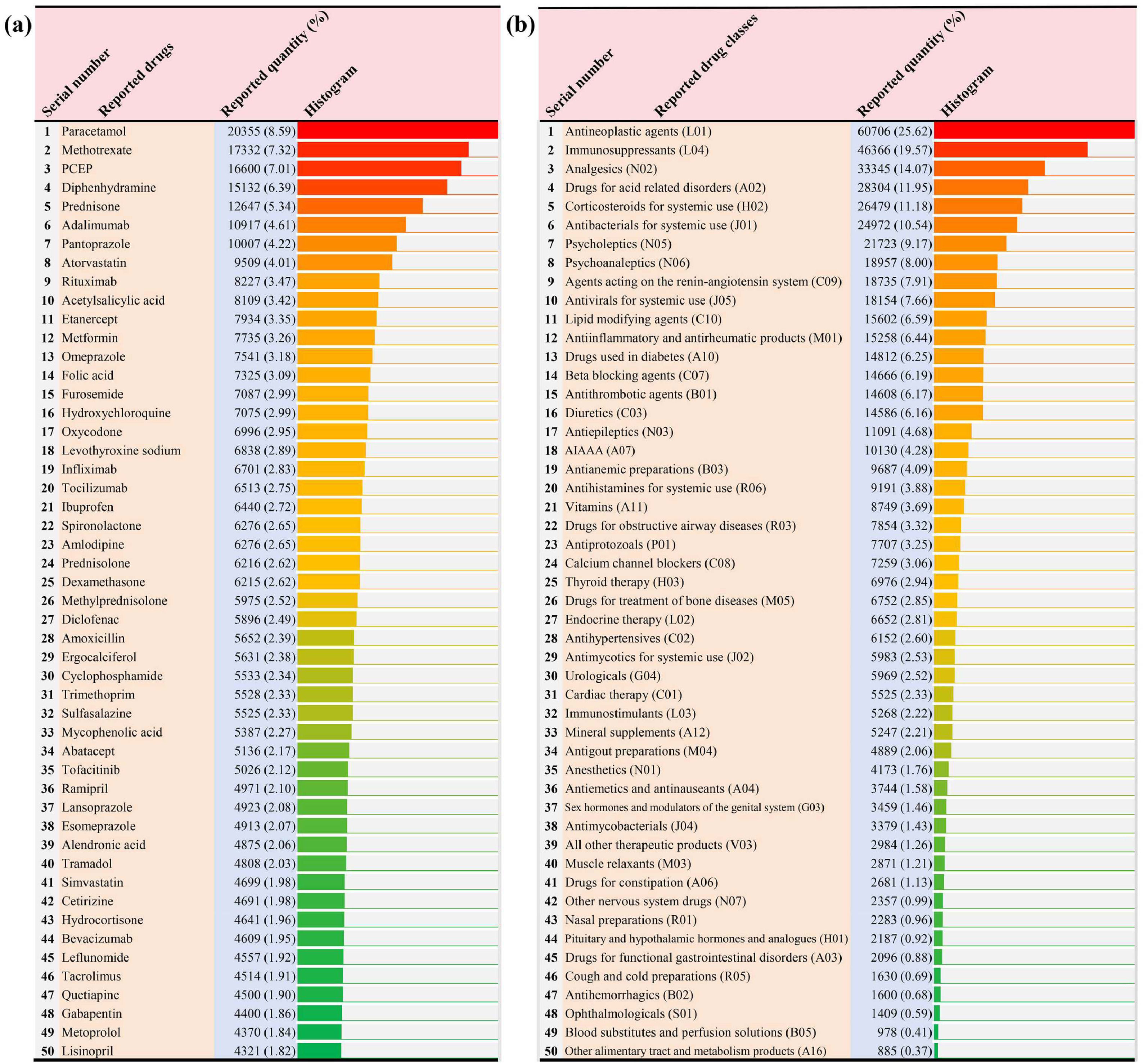

Based on the final culprit-drug list and corresponding drug ATC classification code, we made statistics on the most frequently reported causative single drugs and drug classes, respectively. In single drugs, paracetamol is the most frequently reported, followed by methotrexate, paracetamol combinations excluding psycholeptics, diphenhydramine, prednisone, adalimumab, pantoprazole, atorvastatin, rituximab, and acetylsalicylic acid (Fig. 3a). In drug classes, antineoplastic agents are the most frequently reported, followed by immunosuppressants, analgesics, drugs for acid related disorders, corticosteroids for systemic use, antibacterials for systemic use, psycholeptics, psychoanaleptics, agents acting on the renin-angiotensin system, and antivirals for systemic use (Fig. 3b).

The top 50 most frequently reported single drugs and drug classes in the FAERS database. (a) The top 50 most frequently reported single drugs; (b) The top 50 most frequently reported drug classes. Note: The classification of drugs is based on the pharmacological or therapeutic subgroup (second level) of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system. AIAAA, antidiarrheals, intestinal antiinflammatory/antiinfective agents; PCEP, paracetamol combinations excluding psycholeptics.

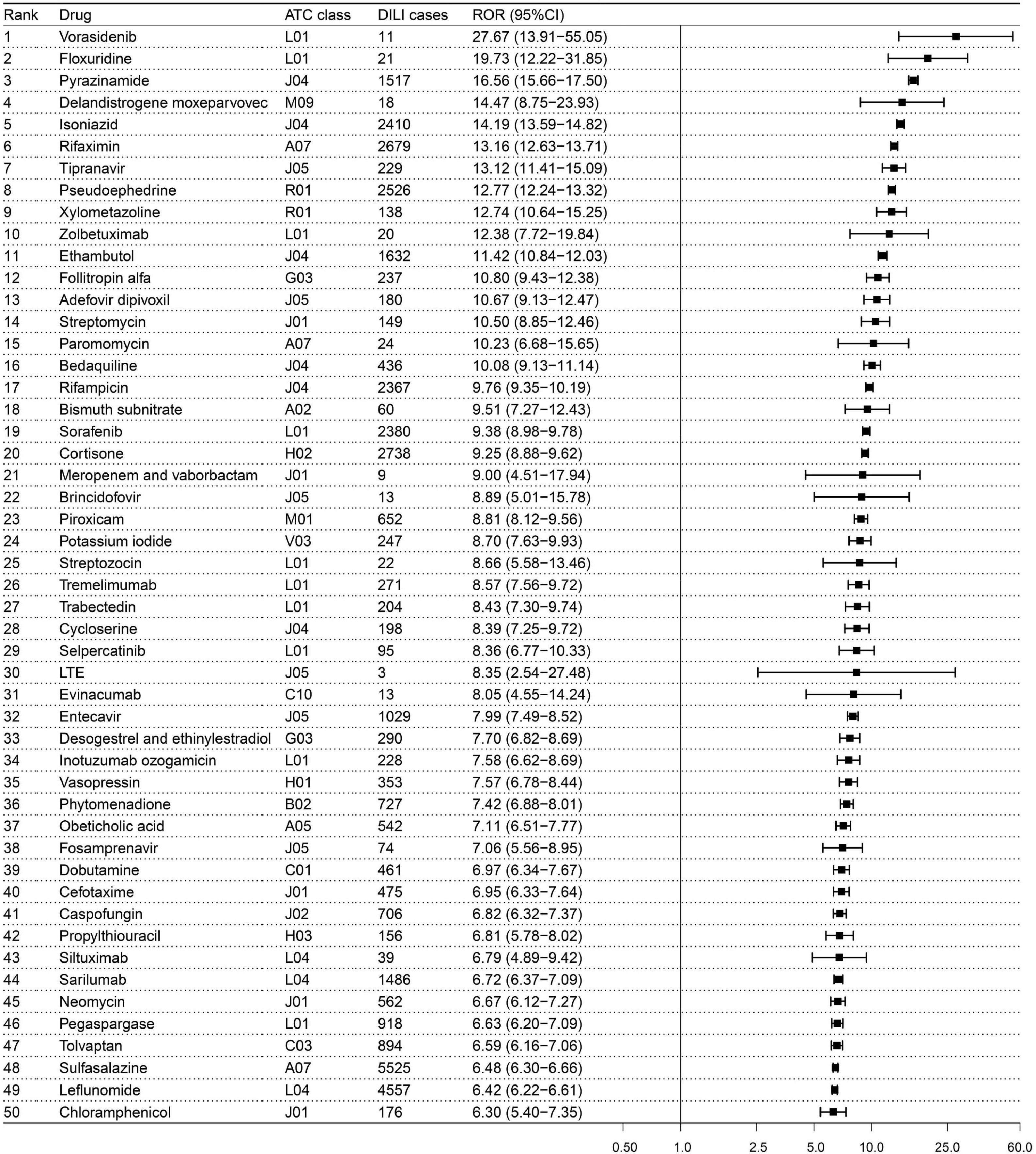

The 1459 reported DILI culprit-drugs in the final list were combined with PTs in Table S1 to detect risk signals, respectively. The risk signal detection result of 1459 drugs was detailed in Table S2 in which 806 drugs exceeded the threshold standard and showed positive signals. Among the 806 drugs with positive signal, vorasidenib (ROR: 27.67, 95 % CI: 13.91–55.05) is the drug with highest signal strength, followed by floxuridine (ROR: 19.73, 95 % CI: 12.22–31.85), pyrazinamide (ROR: 16.56, 95 % CI: 15.66–17.50), delandistrogene moxeparvovec (ROR: 14.47, 95 % CI: 8.75–23.93), isoniazid (ROR: 14.19, 95 % CI: 13.59–14.82) (Fig. 4).

The top 50 drugs with the highest signal strength in the risk detection of liver injury. Note: The classification of drugs is based on the pharmacological or therapeutic subgroup (second level) of Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system. ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical; CI, confidence interval; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; LTE, lamivudine, tenofovir disoproxil and efavirenz; ROR, reporting odds ratio.

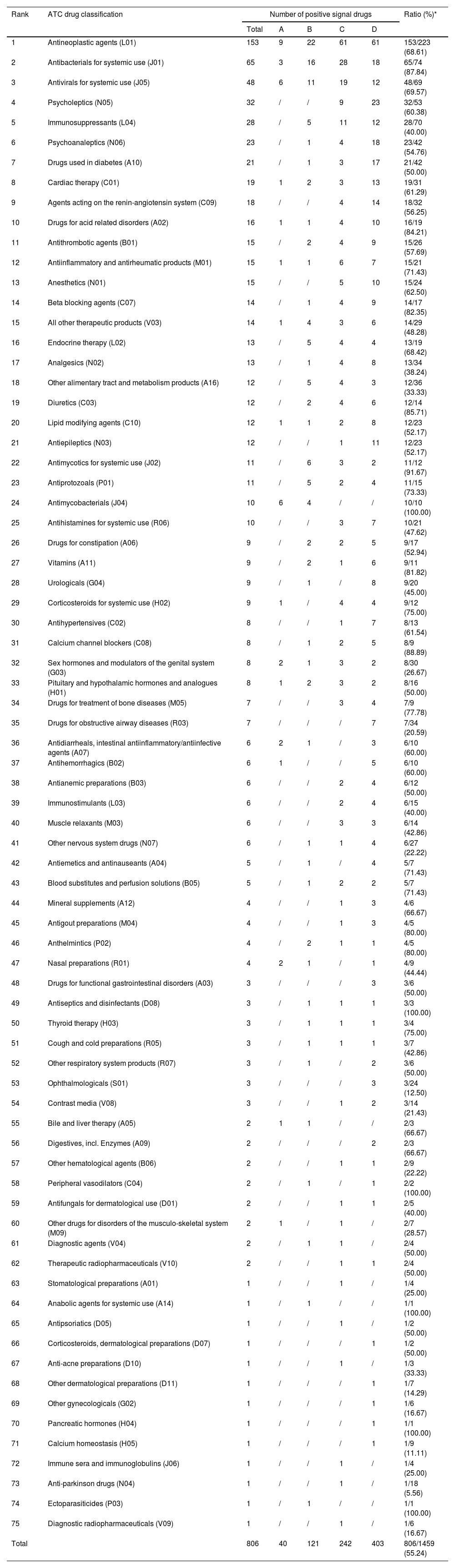

According to the ranking result of signal strength of 806 drugs with positive signal, 40, 121, 242, and 403 drugs were divided into risk levels A, B, C, and D, respectively. Detailed drugs involved in each risk level can be found in Table S3. Meanwhile, based on the ATC classification system, we made statistics on the drug distribution characteristics at four signal strength levels in different drug classes (Table 2). For the 40 level A drugs, the greatest number of drugs were classified into antineoplastic agents (n = 9), followed by antimycobacterials (n = 6) and antivirals for systemic use (n = 6). In addition, antineoplastic agents are also the drug class with the greatest number of drugs among level B, C, and D risk level drugs. In terms of the ratio of positive drugs in different classes, 68.61 % (153/223) of reported antineoplastic agents showed positive DILI risk signal, while the antimycobacterials (10/10) reached 100.00 % (10/10).

The distribution of drug categories of 806 positive signal drugs.

| Rank | ATC drug classification | Number of positive signal drugs | Ratio (%)* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | A | B | C | D | |||

| 1 | Antineoplastic agents (L01) | 153 | 9 | 22 | 61 | 61 | 153/223 (68.61) |

| 2 | Antibacterials for systemic use (J01) | 65 | 3 | 16 | 28 | 18 | 65/74 (87.84) |

| 3 | Antivirals for systemic use (J05) | 48 | 6 | 11 | 19 | 12 | 48/69 (69.57) |

| 4 | Psycholeptics (N05) | 32 | / | / | 9 | 23 | 32/53 (60.38) |

| 5 | Immunosuppressants (L04) | 28 | / | 5 | 11 | 12 | 28/70 (40.00) |

| 6 | Psychoanaleptics (N06) | 23 | / | 1 | 4 | 18 | 23/42 (54.76) |

| 7 | Drugs used in diabetes (A10) | 21 | / | 1 | 3 | 17 | 21/42 (50.00) |

| 8 | Cardiac therapy (C01) | 19 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 13 | 19/31 (61.29) |

| 9 | Agents acting on the renin-angiotensin system (C09) | 18 | / | / | 4 | 14 | 18/32 (56.25) |

| 10 | Drugs for acid related disorders (A02) | 16 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 16/19 (84.21) |

| 11 | Antithrombotic agents (B01) | 15 | / | 2 | 4 | 9 | 15/26 (57.69) |

| 12 | Antiinflammatory and antirheumatic products (M01) | 15 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 15/21 (71.43) |

| 13 | Anesthetics (N01) | 15 | / | / | 5 | 10 | 15/24 (62.50) |

| 14 | Beta blocking agents (C07) | 14 | / | 1 | 4 | 9 | 14/17 (82.35) |

| 15 | All other therapeutic products (V03) | 14 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 14/29 (48.28) |

| 16 | Endocrine therapy (L02) | 13 | / | 5 | 4 | 4 | 13/19 (68.42) |

| 17 | Analgesics (N02) | 13 | / | 1 | 4 | 8 | 13/34 (38.24) |

| 18 | Other alimentary tract and metabolism products (A16) | 12 | / | 5 | 4 | 3 | 12/36 (33.33) |

| 19 | Diuretics (C03) | 12 | / | 2 | 4 | 6 | 12/14 (85.71) |

| 20 | Lipid modifying agents (C10) | 12 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 12/23 (52.17) |

| 21 | Antiepileptics (N03) | 12 | / | / | 1 | 11 | 12/23 (52.17) |

| 22 | Antimycotics for systemic use (J02) | 11 | / | 6 | 3 | 2 | 11/12 (91.67) |

| 23 | Antiprotozoals (P01) | 11 | / | 5 | 2 | 4 | 11/15 (73.33) |

| 24 | Antimycobacterials (J04) | 10 | 6 | 4 | / | / | 10/10 (100.00) |

| 25 | Antihistamines for systemic use (R06) | 10 | / | / | 3 | 7 | 10/21 (47.62) |

| 26 | Drugs for constipation (A06) | 9 | / | 2 | 2 | 5 | 9/17 (52.94) |

| 27 | Vitamins (A11) | 9 | / | 2 | 1 | 6 | 9/11 (81.82) |

| 28 | Urologicals (G04) | 9 | / | 1 | / | 8 | 9/20 (45.00) |

| 29 | Corticosteroids for systemic use (H02) | 9 | 1 | / | 4 | 4 | 9/12 (75.00) |

| 30 | Antihypertensives (C02) | 8 | / | / | 1 | 7 | 8/13 (61.54) |

| 31 | Calcium channel blockers (C08) | 8 | / | 1 | 2 | 5 | 8/9 (88.89) |

| 32 | Sex hormones and modulators of the genital system (G03) | 8 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 8/30 (26.67) |

| 33 | Pituitary and hypothalamic hormones and analogues (H01) | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 8/16 (50.00) |

| 34 | Drugs for treatment of bone diseases (M05) | 7 | / | / | 3 | 4 | 7/9 (77.78) |

| 35 | Drugs for obstructive airway diseases (R03) | 7 | / | / | / | 7 | 7/34 (20.59) |

| 36 | Antidiarrheals, intestinal antiinflammatory/antiinfective agents (A07) | 6 | 2 | 1 | / | 3 | 6/10 (60.00) |

| 37 | Antihemorrhagics (B02) | 6 | 1 | / | / | 5 | 6/10 (60.00) |

| 38 | Antianemic preparations (B03) | 6 | / | / | 2 | 4 | 6/12 (50.00) |

| 39 | Immunostimulants (L03) | 6 | / | / | 2 | 4 | 6/15 (40.00) |

| 40 | Muscle relaxants (M03) | 6 | / | / | 3 | 3 | 6/14 (42.86) |

| 41 | Other nervous system drugs (N07) | 6 | / | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6/27 (22.22) |

| 42 | Antiemetics and antinauseants (A04) | 5 | / | 1 | / | 4 | 5/7 (71.43) |

| 43 | Blood substitutes and perfusion solutions (B05) | 5 | / | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5/7 (71.43) |

| 44 | Mineral supplements (A12) | 4 | / | / | 1 | 3 | 4/6 (66.67) |

| 45 | Antigout preparations (M04) | 4 | / | / | 1 | 3 | 4/5 (80.00) |

| 46 | Anthelmintics (P02) | 4 | / | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4/5 (80.00) |

| 47 | Nasal preparations (R01) | 4 | 2 | 1 | / | 1 | 4/9 (44.44) |

| 48 | Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders (A03) | 3 | / | / | / | 3 | 3/6 (50.00) |

| 49 | Antiseptics and disinfectants (D08) | 3 | / | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3/3 (100.00) |

| 50 | Thyroid therapy (H03) | 3 | / | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3/4 (75.00) |

| 51 | Cough and cold preparations (R05) | 3 | / | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3/7 (42.86) |

| 52 | Other respiratory system products (R07) | 3 | / | 1 | / | 2 | 3/6 (50.00) |

| 53 | Ophthalmologicals (S01) | 3 | / | / | / | 3 | 3/24 (12.50) |

| 54 | Contrast media (V08) | 3 | / | / | 1 | 2 | 3/14 (21.43) |

| 55 | Bile and liver therapy (A05) | 2 | 1 | 1 | / | / | 2/3 (66.67) |

| 56 | Digestives, incl. Enzymes (A09) | 2 | / | / | / | 2 | 2/3 (66.67) |

| 57 | Other hematological agents (B06) | 2 | / | / | 1 | 1 | 2/9 (22.22) |

| 58 | Peripheral vasodilators (C04) | 2 | / | 1 | / | 1 | 2/2 (100.00) |

| 59 | Antifungals for dermatological use (D01) | 2 | / | / | 1 | 1 | 2/5 (40.00) |

| 60 | Other drugs for disorders of the musculo-skeletal system (M09) | 2 | 1 | / | 1 | / | 2/7 (28.57) |

| 61 | Diagnostic agents (V04) | 2 | / | 1 | 1 | / | 2/4 (50.00) |

| 62 | Therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals (V10) | 2 | / | / | 1 | 1 | 2/4 (50.00) |

| 63 | Stomatological preparations (A01) | 1 | / | / | 1 | / | 1/4 (25.00) |

| 64 | Anabolic agents for systemic use (A14) | 1 | / | 1 | / | / | 1/1 (100.00) |

| 65 | Antipsoriatics (D05) | 1 | / | / | 1 | / | 1/2 (50.00) |

| 66 | Corticosteroids, dermatological preparations (D07) | 1 | / | / | / | 1 | 1/2 (50.00) |

| 67 | Anti-acne preparations (D10) | 1 | / | / | 1 | / | 1/3 (33.33) |

| 68 | Other dermatological preparations (D11) | 1 | / | / | / | 1 | 1/7 (14.29) |

| 69 | Other gynecologicals (G02) | 1 | / | / | / | 1 | 1/6 (16.67) |

| 70 | Pancreatic hormones (H04) | 1 | / | / | / | 1 | 1/1 (100.00) |

| 71 | Calcium homeostasis (H05) | 1 | / | / | / | 1 | 1/9 (11.11) |

| 72 | Immune sera and immunoglobulins (J06) | 1 | / | / | 1 | / | 1/4 (25.00) |

| 73 | Anti-parkinson drugs (N04) | 1 | / | / | 1 | / | 1/18 (5.56) |

| 74 | Ectoparasiticides (P03) | 1 | / | 1 | / | / | 1/1 (100.00) |

| 75 | Diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals (V09) | 1 | / | / | 1 | / | 1/6 (16.67) |

| Total | 806 | 40 | 121 | 242 | 403 | 806/1459 (55.24) | |

Note:.

DILI is a potentially life-threatening drug safety problem that has attracted wide attention from gastroenterologists, pharmacologists, drug manufacturers, and regulatory agencies worldwide. Spontaneous reporting database is an important component of drug post-marketing monitoring, providing an opportunity for understanding drug safety. In this study, we comprehensively reviewed and analyzed the AE reports related to liver injury in the FAERS database from 2004 to 2024, so as to provide the latest information for clinical practice on the potential risk of drug hepatotoxicity.

Compared with previous studies using spontaneous report databases to explore drug hepatotoxicity, our study has the following advantages. First, our study used the latest updated annual AE report data in the FAERS database, which is at least five years ahead compared to other similar studies and can better reflect the current landscape of DILI in the real world [21–23]. Second, our study summarized a detailed list containing 1459 reported DILI culprit-drugs and accordingly provided the number of reports and signal detection results related to each drug (Table S2). By contrast, previous studies usually focused on limited single drugs [30,31], single drug classes [32,33], or some drugs with the highest reporting frequency or signal strength [23]. Due to the differences in research methods and time limits, it is difficult to integrate and compare the results of different studies. In this regard, we analyzed 1459 drugs with a unified standard, which broke the barrier of incomparable drug risk results among different studies and facilitated the understanding of potential differences in DILI risks among drugs. Finally, different from other similar studies [21–23], we also pay extra attention to the risk differences between drug classes. In this study, we displayed the most frequently reported drug classes (Fig. 3b) and showed the distribution characteristics of drug risk levels in different drug classes based on the stratifying result of positive signal drugs (Table 2). To our knowledge, there is no similar analysis in previous pharmacovigilance studies, and our results add new information for understanding the potential risks of DILI among different drug classes.

Through the comprehensive analysis of AE reports about liver injury in the FAERS database, we also have some new findings. In previous studies, antibiotics, cardiovascular agents, psychotropic, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were reported as the main DILI-causative drug classes worldwide [14]. However, our results showed that although some of the representative drugs (e.g. amoxicillin, atorvastatin, quetiapine, and paracetamol) in the above-mentioned drug classes have a place in the most frequently reported single drugs (Fig. 3a), on the whole, antineoplastic agents have replaced them as the most frequently reported drug class leading to DILI (Fig. 3b). Perhaps the sudden emergence of antineoplastic agents can be partly attributed to its huge drug quantity base (Fig. 2b), but some antineoplastic agents (e.g., rituximab, cyclophosphamide, and bevacizumab) are also conspicuous in the ranking of reported quantity (Fig. 3a). Therefore, it is necessary to be more alert to the potential hepatotoxicity of antineoplastic agents in clinical practice and drug safety supervision in the future.

Of course, we also realized that although the high reporting frequency of drugs can reflect their potential hepatotoxicity risk to some extent, the difference in drug use frequency in the real world greatly affects this figure. In the drug epidemiological investigation, incidence is the gold standard to reflect the DILI risk difference between drugs. However, due to a lack of the exact number of patients exposed to drugs and the corresponding number of patients suffering liver injury, it is difficult to determine the actual incidence of DILI caused by each drug to compare the risk differences between drugs. Therefore, in the cases of the DILI incidence of most drugs is not available, we introduced the disproportionality analysis as an alternative indicator to evaluate and quantify the potential DILI risk of different drugs. In addition to some notorious hepatotoxic drugs (e.g., isoniazid, rifampicin, and pyrazinamide) showing high risk signals, our results also highlighted that some newly-marketed antineoplastic agents (e.g., vorasidenib ranked first in signal strength) and gene therapy drugs (e.g., delandistrogene moxeparvovec ranked fourth in signal strength) may have a high risk of liver injury during medication use (Fig. 4). Vorasidenib is an orally administered, brain-penetrant dual inhibitor of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1 and 2 enzymes, which was first approved for the treatment of adult and pediatric patients aged 12 years and older with grade 2 astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma with a susceptible IDH1 or IDH2 mutation in the USA on 6 August 2024 [34]. Delandistrogene moxeparvovec is an adeno-associated virus vector-based gene therapy, which was first approved for the treatment of pediatric patients aged 4 through 5 years with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and a confirmed mutation in the dystrophin gene in the USA in June 2023 [35]. In previous clinical trials, vorasidenib and delandistrogene moxeparvovec have been observed to have a significantly higher DILI risk than placebo [36,37], which partly verified the reliability of our results. In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to the hepatotoxicity of new therapies such as gene therapy and novel antineoplastic drugs [17,18], and our study provided additional information for understanding the hepatotoxicity of new therapies from the perspective of post-marketing pharmacovigilance.

Additionally, based on the risk signal detection results (Table S2 and S3), we further summarized the distribution characteristics of 806 positive signal drugs in different drug classes (Table 2). Our results showed that among all drug classes, antineoplastic agents had the largest number (n = 153) of positive signal drugs and occupied a dominant position (9/40) in high-risk (Level A) drugs. In a previous study, Bjornsson ES et al. tried to analyze the hepatotoxicity of different drugs based on LiverTox (http://livertox.nlm.nih.gov) [38]. Their results showed that although antineoplastic agent has a place in the high-risk drug category, its overall DILI risk ranks behind antimicrobials, drugs acting on the central nervous system, cardiovascular, and rheumatologic. In contrast, our results emphasized the prominent position of antineoplastic agents in many drug classes with potential DILI risk. Moreover, we also found there are big differences in the specific high-risk DILI drug emphasized. The results of Bjornsson ES et al. mainly suggested the high DILI risk of old antineoplastic agents (e.g. busulfan, floxuridine, and thioguanine) [38], while our study mainly highlighted the high DILI risk of many new generation antineoplastic agents (e.g. vorasidenib, zolbetuximab, and sorafenib). In our opinion, such a difference is largely attributed to the development and application of anti-tumor drugs in recent years, while our results once again emphasized the emerging important role of new antineoplastic agents in DILI. In addition to antineoplastic agents, we also noticed that some classic drug classes with potential hepatotoxicity such as antimycobacterials (10/10, 100.00 %), antimycotics for systemic use (11/12, 91.67 %), and antibacterials for systemic use (65/74, 87.84 %) have a relatively high proportion of positive signal drugs. The above-mentioned results aligned with the known knowledge of hepatotoxicity and also suggested the necessity of continuous attention to the DILI risk of these drug classes during medication use in clinical practice. In general, according to analyzing the distribution characteristics of positive signal drugs, our study provided a direction for the focus of drug monitoring of DILI culprit-drugs in the future to some extent.

However, although our study provided updated information for clinical practice and drug supervision by a comprehensive analysis of AE reports on liver injury in the FAERS database, several limitations of this study must be mentioned. First, the FAERS database is a pharmacovigilance database with a voluntary reporting nature, and the existence of under-reporting, duplicate reporting, notoriety bias, and Weber effect in the spontaneous reporting database will inevitably damage the accuracy of our data [27]. Second, the reported DILI cases in the FAERS database lack laboratory values, imaging findings, biopsy results, and some other clinical details, which are important for understanding DILI phenotyping and risk drug involved. Therefore, it is necessary to further verify results presented in this study to enhance diagnostic accuracy and subtype classification by integrating biopsy-confirmed DILI registry data in future study. Third, some diseases-induced liver injury may be wrongly attributed to drug-induced and lead to an abnormal increase in the reporting frequency of specific drugs. For example, prednisone ranks fifth in the most frequently reported single drug (Fig. 3a), but it is often used in patients with pre-existing liver inflammation (e.g., autoimmune hepatitis). In this case, the results of drugs with high reporting frequency need to be interpreted cautiously, because it is difficult to completely attribute the reported liver injury to the drug itself. Fourth, in the process of diagnosing DILI, causality assessment scales such as Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method are recommended to establish the causality between drug use and DILI occurrence [39], but the DILI reports submitted to FAERS may not have undergone a similar rigorous assessment, which may lead to the wrong identification of the culprit-drugs and bring potential result bias. Fifth, multiple factors such as age, sex, polypharmacy, comorbidities, alcohol use, and pre-existing liver disease may increase the risk of DILI [2], but due to the inherent limitations of the FAERS database, it is almost impossible to eliminate the influence of these confounding factors in signal detection. Sixth, the detection results of positive signals only represent the statistical relationship between drug use and liver injury, and whether there is a causal relationship still needs further verification in the clinic. Finally, although the FAERS database receives AE reports from all over the world, the main source is still the United States, so the results obtained from the FAERS database may still not fully represent the global drug use pattern or DILI epidemiology.

5ConclusionsThis study summarized a list of drugs containing 1459 reported potential culprit-drugs by comprehensively reviewing the AE reports related to liver injury in the FAERS database from 2004 to 2024. Based on the summarized list, we made statistics on the most frequently reported single drugs and drug classes and conducted risk signal detection for 1459 drugs respectively. Our results showed 806 of 1459 drugs have a positive risk signal, suggesting that these drugs have potential DILI risk during medication use. In addition, our results showed that antineoplastic agents occupy a prominent position in reporting frequency of classes, risk signal strength of single drug, number of positive signal drugs, and high-risk drug distribution, suggesting that we may need to pay more attention to the liver injury risk of antineoplastic agents in clinical practice and drug safety supervision in the future.

FundingThis work was supported by the Research Incubation Project of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (KY24038), Medical research project of Chongqing Municipal Health and Wellness Committee (2025WSJK101), and Key Specialty Construction Project of Clinical Pharmacy in Chongqing.

Author contributionsConceptualization, D.L. and Q.D.; methodology, D.L. and D.W.; software, D.L.; data curation, D.L., D.W., G.H., Q.L., Y.W. and R.Z.; writing-original draft preparation, D.L.; writing—review and editing, D.L., D.W., G.H., Q.L., Y.W., R.Z., S.L., and Q.D; visualization, D.L.; funding acquisition, D.L., G.H., and Q.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. D.L. is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole.

None.