Primary liver cancers represent a major global health burden, with an estimated 865,000 new cases and 757,948 deaths worldwide in 2022 [1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) are the most common histological subtypes [2]. HCC, originating from hepatocytes, accounts for 75–85 % of cases, while iCCA, arising from biliary epithelial cells, represents 10–15 % [2]. Although both originate in the liver, they differ substantially in molecular features and clinical prognoses [3,4].

Incidence patterns for HCC and iCCA vary widely across regions[2], reflecting differences in the distribution of known risk factors [5]. Recent evidence indicates partial convergence in etiology, with hepatitis B and C virus infections, obesity, diabetes, and metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) implicated in both cancers [6,7]. However, the full spectrum of shared and subtype-specific risk factors remains insufficiently characterized, hindering efforts to reduce liver cancer burden—particularly in regions where incidence is rising, such as Europe, North America, and parts of South America [8–10].

Improved understanding of modifiable risk factors for HCC and iCCA is essential for advancing prevention, early detection, and personalized treatment. It may also clarify their etiological distinctions and guide future research and policy. In this study, we first examine global incidence patterns using the most recent cancer registry data. We then comprehensively assess a wide array of modifiable risk factors and estimate their contributions to disease burden using population-attributable fractions. By quantifying preventable proportions, our findings aim to support evidence-based strategies for liver cancer prevention and control.

2Materials and Methods2.1Data sources of incidence ratesWe obtained liver cancer incidence data by histological subtype from Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (CI5) Volume XII, which compiles data from 455 cancer registries covering 588 populations in 70 countries during 2013–2017. Liver cancer subtypes were classified using International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3), morphology codes: hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, 8170–8175) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA, 8050, 8140–8141, 8160–8161, 8260, 8440, 8480–8500, 8570–8572) [2].

To ensure data quality, we excluded registries where more than 30 % of liver cancer cases lacked histological subtype, a stricter criterion than the 75 % threshold used in prior studies [2]. For countries with multiple registries, we retained only the most comprehensive. This process yielded 149 cancer registries from 49 countries (Table S1). Age-standardized incidence rates (ASRs) for HCC and iCCA were calculated using the Segi-Doll world standard population. We also computed incidence rate ratios and compared geographic variation using the coefficient of variation (CV), defined as the standard deviation divided by the mean ASR.

2.2Assessment of risk factors in the UK BiobankWe analyzed epidemiological and genetic data from the UK Biobank (UKBB), a prospective cohort of over 500,000 participants aged 40–69 years at recruitment [11]. Individuals with a history of cancer at baseline were excluded (n = 19,096; Table S2), resulting in 481,841 participants for analysis. Incident HCC and iCCA cases were identified through linkage with national cancer and death registries using ICD-10 codes C22.0 and C22.1, respectively. To reduce potential confounding from other cancers, participants were censored at the first diagnosis of any malignancy (n = 36). To independently investigate HCC and iCCA, we constructed two non-overlapping datasets. In each, individuals who developed the alternative liver cancer subtype were excluded. This yielded 481,394 participants in the HCC dataset and 481,432 in the iCCA dataset.

Modifiable risk factors were defined as those that can be altered through behavioral, clinical, or public health interventions [12]. We assessed associations between five categories of risk factors and the risk of HCC and iCCA using Cox proportional hazards models. These categories included: (1) demographic and lifestyle factors (n = 9); (2) anthropometric measures (n = 5); (3) baseline chronic digestive diseases (n = 15); (4) blood traits (n = 29); and (5) blood biochemical markers (n = 29). Full definitions are provided in Tables S3–S5. Models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, household income, BMI, education deprivation score, smoking status, alcohol intake frequency, and physical activity level. Incident liver cancer cases during follow-up served as the case group; all others were considered controls. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were used to quantify associations.

Subgroup analyses were performed by age (<60 vs ≥60 years), sex, follow-up time (<5 vs ≥5 years), and genetic risk of chronic liver disease. Genetic risk was assessed using five liver disease-associated variants: PNPLA3 rs738409, TM6SF2 rs58542926, GCKR rs1260326, MBOAT7 rs641738, and HSD17B13 rs72613567 [13]. A genetic risk score (GRS) was calculated by summing risk alleles across these variants, and participants were classified into high or low genetic risk based on the median GRS.

To assess whether the same risk factor had differing associations with HCC and iCCA, we compared the HRs for each cancer using a Z-test on the ratio of HRs. This approach evaluates whether the relative effect of a given exposure differs significantly between the two outcomes. Specifically, we computed the ratio r=HR1HR2, where HR1 and HR2 represent the HRs for HCC and iCCA, respectively. The standard error (SE) of the ratio was calculated as:

where SE1 and SE2 are the standard errors of HR1 and HR2, respectively. Subsequently, a z-score is computed using z=r−1SEr, which standardizes the ratio against the null hypothesis of no difference (ratio of 1). A two-sided p-value was calculated from the z-score to assess statistical significance. A p-value < 0.05 was considered indicative of a differential association with HCC versus iCCA.2.3Mendelian randomization analysisTo explore the potential causal effects of key risk factors on liver cancer, we performed two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis using genetic variants as instrumental variables. This method mitigates bias from confounding and reverse causality [14]. Genetic summary data for the risk factors were retrieved from previous GWASs or UKBB if available. GWAS summary data of HCC and iCCA were retrieved from FinnGen [15], a public-private partnership project combining genotype data from Finnish biobanks and digital health record data from Finnish health registries (https://finngen.gitbook.io/documentation/). Detailed MR procedures and sensitivity analyses are provided in the Supplementary Methods [16].

2.4Population attributable fractionTo quantify the proportion of HCC and iCCA cases attributable to modifiable exposures, we estimated adjusted population attributable fractions (adjPAFs) for each risk factor using Bruzzi’s method [17]. This approach accounts for both the strength of the association (e.g., HR) and the prevalence of the exposure, offering a population-level estimate of preventable disease burden. Modifiable risk factors were defined as those that can be altered through behavioral, clinical, or public health interventions, including lifestyle behaviors, metabolic traits, pre-existing digestive conditions, and circulating biomarkers [12]. Risk factors were transformed into binary (e.g., smoking: yes/no) or categorical (e.g., liver enzyme quartiles) variables. Models were adjusted for the same covariates as in the main Cox models. The adjPAF was computed using the following formula:

where ρq,k denotes the proportion of cases in exposure level q within stratum k, and RRq|k represents the relative risk compared to the reference group.To evaluate the combined preventable burden of multiple risk factors, we calculated the average sequential PAF (averPAF), which considers the cumulative effect of removing multiple exposures in all possible orders [17]. The averPAF for the lllth factor is given by:

where γ is a generic removal order and GL is the set of all possible L! removal orders. Risk factors were included in a multivariable logistic regression model after transformation into binary or categorical formats. Covariate adjustment matched that of the Cox model. To reduce collinearity among biomarkers, we calculated pairwise Pearson correlations and excluded one biomarker from any pair with r > 0.75, retaining the one with the higher HR. For negatively associated biomarkers, exposure levels were reversed to reflect risk-increasing effects. Cases were matched 1:5 to cancer-free controls on age and sex to facilitate computation. All statistical analyses were performed using R program (R core team, v4.3.1).2.5Ethical statementsThis study was conducted using the UKBB resource. All participants gave written informed consent prior to data collection. The UK Biobank has full ethical approval from the NHS National Research Ethics Service (16/NW/0274).

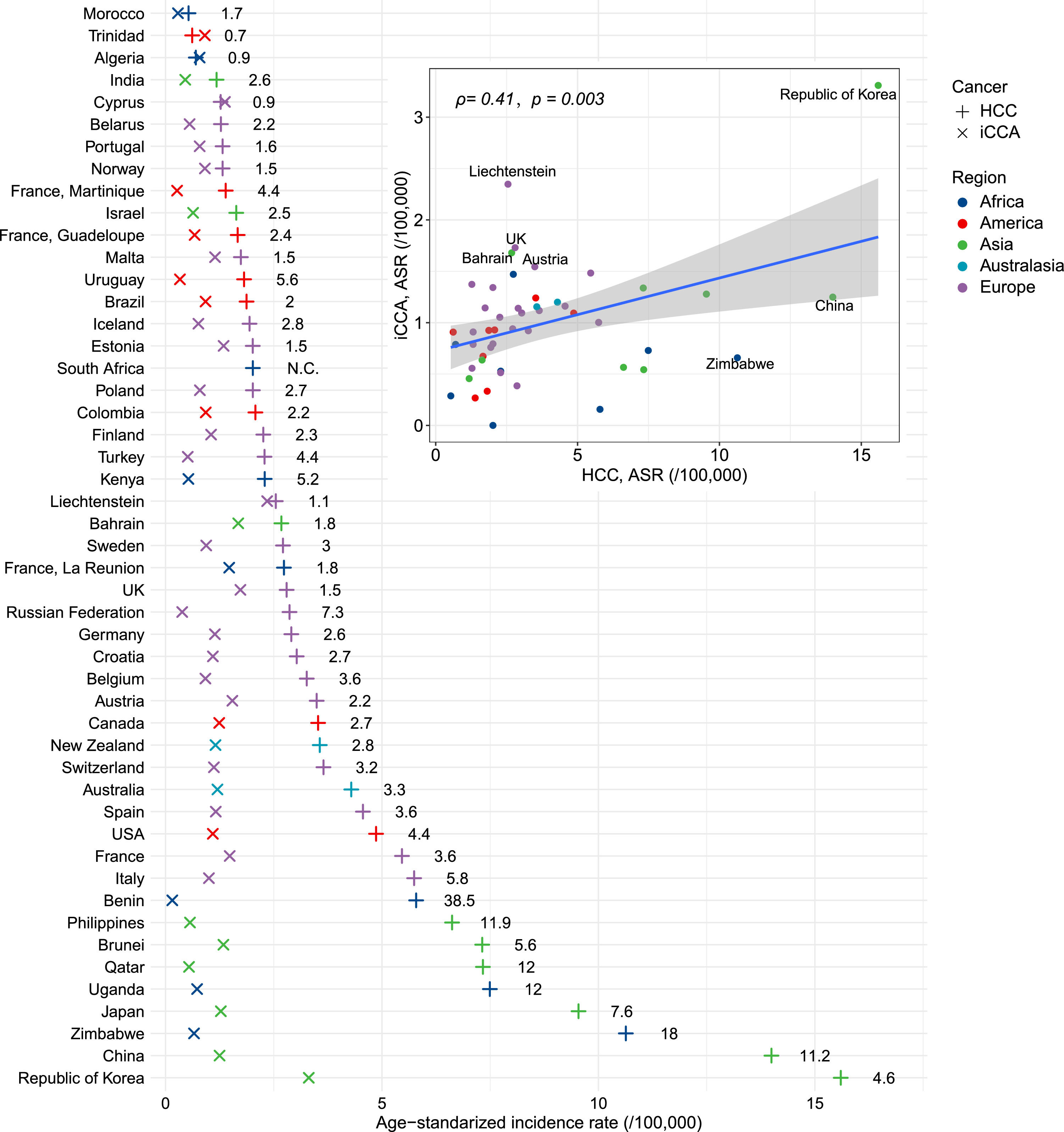

3Results3.1Global incidence patternsWe observed a moderate positive correlation between the age-standardized incidence rates (ASRs) of HCC and iCCA across countries (Pearson’s r = 0.41, P = 0.003) (Fig. 1). HCC displayed wide geographic variation, with a nearly 30-fold difference in ASRs. The highest incidence was recorded in the Republic of Korea (15.6 per 100,000), followed by China and Zimbabwe (Fig. 1; Table S6). In comparison, iCCA showed less variation (coefficient of variation: 56 % vs. 86 % for HCC), with the Republic of Korea again having the highest rate (3.3 per 100,000), followed by Liechtenstein and the UK. Notably, only three countries—Cyprus, Algeria, and Trinidad—reported higher iCCA than HCC incidence. The HCC-to-iCCA incidence ratio ranged from 38.5 in Benin to 0.7 in Trinidad.

The age-standardized incidence rates (ASR) of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) across the world. The numbers in the figure denote incidence rate ratio in each country. The inserted panel showcases the correlation between ASRs of HCC and iCCA. The correlation index and its p-value were calculated from Pearson correlation test.

Of the 481,841 eligible individuals (mean [standard deviation] age = 56.9 [8.1] years; 54.1 % females), 470 HCC cases and 508 iCCA cases occurred during the median follow-up of 13.8 years to 31 Oct, 2022 (Table 1). The crude incidence rate of HCC and iCCA was 6.8/100,000 and 7.3/100,000, respectively. Fifteen chronic digestive conditions were documented at baseline, with prevalence ranging from 0.03 % for primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) to 1.74 % for nonspecific gastritis (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of study participants from the UK Biobank cohort.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Total | 481,841 (100) |

| HCC cases (incidence rate) | 470 (6.8/100,000) |

| iCCA cases (incidence rate) | 508 (7.3/100,000) |

| Mean age (SD), years | 56.9 (8.1) |

| Women | 260,769 (54.1) |

| Median education deprivation score (IQR) | 10.0 (3.9, 21.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 452,335 (93.9) |

| Others or unknown | 29,506 (6.1) |

| Average total household income before tax (£) | |

| Less than 18,000 | 92,264 (19.1) |

| 18,000 to 30,999 | 175,946 (36.5) |

| 31,000 to 51,999 | 107,080 (22.2) |

| 52,000 to 100,000 | 84,142 (17.5) |

| Greater than 100,000 | 22,409 (4.7) |

| BMI categories (kg/m2) | |

| < 25 | 158,421 (32.9) |

| 25–29.9 | 206,516 (42.8) |

| >=30 | 116,904 (24.3) |

| Alcohol intake frequency | |

| Never or special occasions only | 93,872 (19.5) |

| ≤ Twice a week | 179,008 (37.1) |

| Three times or more a week | 208,961 (43.4) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 265,992 (55.2) |

| Previous | 164,818 (34.2) |

| Current | 51,031 (10.6) |

| Physical activity level† | |

| 0–1 day/week | 95,237 (19.8) |

| 2–4 days/week | 205,996 (42.8) |

| ≥5 days/week | 179,764 (37.4) |

| HBV/HCV status* | |

| Positive | 248 (2.7) |

| Negative | 8813 (97.3) |

| Baseline chronic digestive diseases | |

| Chronic liver diseases | 1962 (0.41) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 628 (0.13) |

| Crohn’s disease | 1266 (0.26) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2305 (0.48) |

| Duodenal ulcer | 2107 (0.44) |

| Peptic ulcer | 285 (0.06) |

| Gastric ulcer | 2450 (0.51) |

| Superficial gastritis | 218 (0.05) |

| Atrophic gastritis | 197 (0.04) |

| Unspecific gastritis | 8389 (1.74) |

| Duodenitis | 5004 (1.04) |

| Cholelithiasis | 8798 (1.83) |

| Cholecystitis | 1755 (0.36) |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 150 (0.03) |

| Obstruction of bile duct | 258 (0.05) |

Values are numbers (percentage at column) unless stated otherwise.

Abbreviations: BMI, body-mass index; SD, standard deviation; IQR, inter-quartile range; HBV/HCV, hepatitis B/C virus.

We examined 87 risk factors (Table S7), of which 44 remained statistically significant for HCC after Bonferroni correction (P < 5.75×10−4). Age was positively associated with both cancers (per 5-year increase: HR = 1.48 for HCC; HR = 1.52 for iCCA). Male sex was a strong risk factor for HCC (HR = 3.64, 95 % CI: 2.93–4.53) but not for iCCA (Fig. 2). For HCC, the strongest risk associations were observed for liver cirrhosis (HR = 40.12, 95 % CI: 28.33–56.82), chronic liver disease (HR = 26.67, 95 % CI: 20.36–34.93), and PSC (HR = 17.35, 95 % CI: 6.47–46.48). For iCCA, in addition to age, eight other factors remained significant after p-value correction: smoking, BMI, chronic liver disease, liver cirrhosis, PSC, Crohn’s disease, gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). PSC was the most prominent iCCA risk factor (HR = 30.79, 95 % CI: 13.74–68.97).

The associations of potential risk factors with the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA). The hazard ratio (HR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by Cox regression model. The hollow dots denote statistically non-significant associations (P > 0.05). The p-value for HR heterogeneity was calculated from the HR ratio test.

Although most risk factors had consistent directions of effect for both cancers, their magnitudes differed significantly (P for HR heterogeneity < 0.05). Risk estimates were generally stronger for HCC than iCCA. For example, a 5-unit increase in BMI was associated with a higher HR for HCC (1.45) than iCCA (1.19, P = 1.32×10−4). Similarly, a 1-SD increase in IGF-1 corresponded to a 74 % lower HCC risk versus a 22 % reduction for iCCA (P < 2.2×10−16). Exceptions included PSC, Crohn’s disease, and cholecystitis, which showed stronger associations with iCCA.

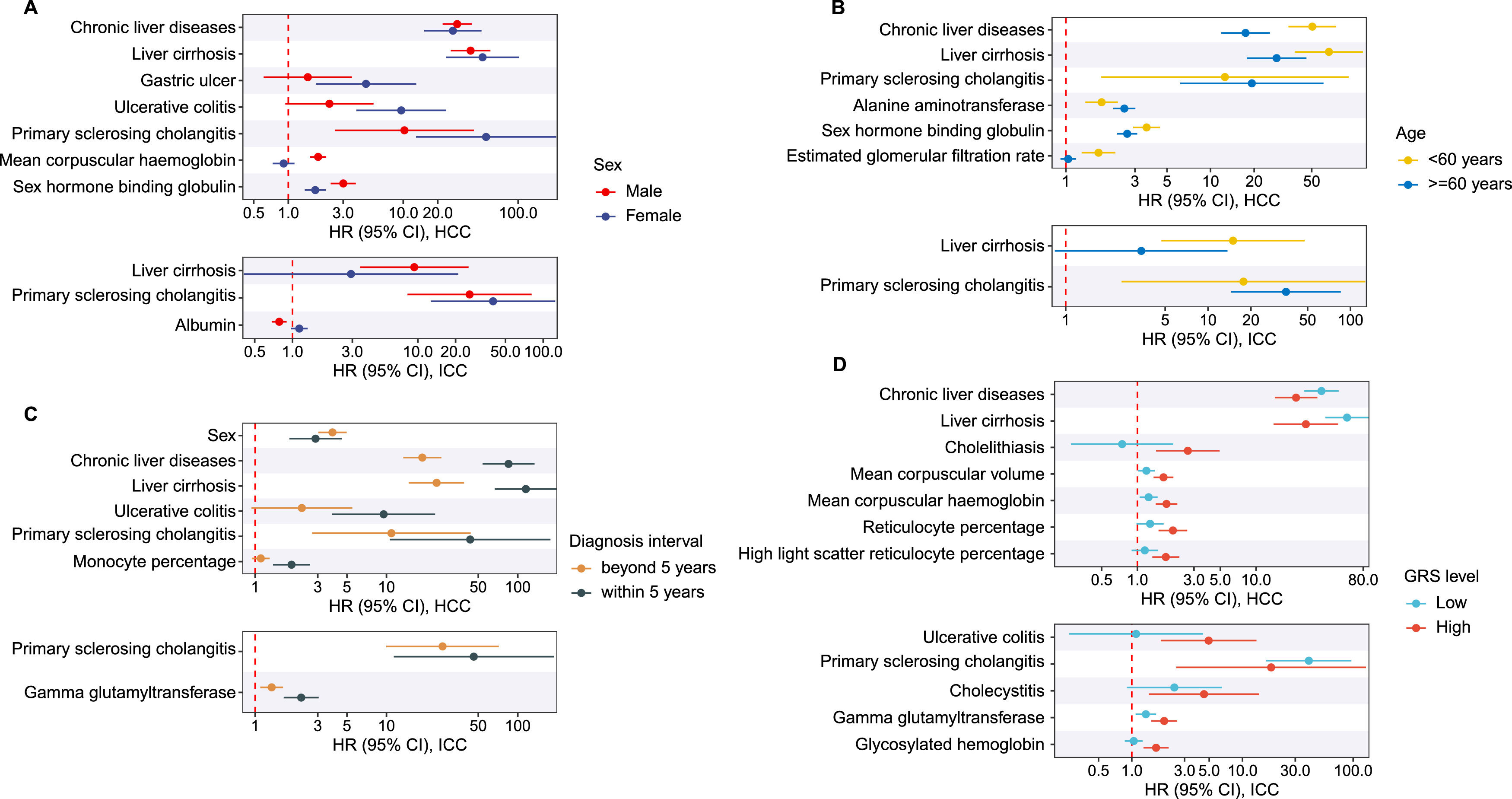

3.3Subgroup analysesSubgroup analyses revealed no contradictory findings but did show varying magnitudes across strata (Fig. 3; Tables S8–S11). For example, baseline chronic liver disease was associated with a 50-fold increased HCC risk among participants < 60 years and a 34-fold increase among those with low genetic risk, significantly higher than their respective counterparts. Liver cirrhosis conferred a 115-fold increased risk for HCC diagnosed within five years of follow-up, compared to 24-fold beyond five years. The overall pattern of stronger effects for HCC remained consistent across subgroups. Sex-stratified analyses showed that most risk factors remained significant in both sexes, but their effect sizes differed. Moreover, some factors like waist-hip ratio and body fat percentage were associated with HCC and iCCA only in men, underscoring pronounced sex-specific heterogeneity (Table S8).

Associations between modifiable risk factors and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) across subgroups. A - D panel shows subgroup analysis on sex, age, follow-up duration of liver cancer cases, and genetic risk score (GRS), respectively. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by Cox regression model. The figure only displays risk factors that showed significant HR-heterogeneity (P < 5.75E-4) between subgroups.

The GWAS summary data for the risk factors are provided in Table S12. MR analysis indicated that genetically predicted waist-hip ratio, chronic liver disease, liver cirrhosis, cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), albumin, phosphate, GGT, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were causally associated with an increased risk of HCC. Protective associations were observed for genetically predicted smoking cessation, LDL-C, cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B (Table S13). The associations between chronic liver disease, liver cirrhosis, ALT, cholesterol, AST, and HCC remained significant after p-value correction. For iCCA, MR identified causal effects of BMI, waist-hip ratio, smoking initiation, chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, and ALT. Conversely, higher genetically predicted body fat percentage, LDL-C, cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B were associated with lower iCCA risk. Significant associations after correction were observed for chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, ALT, LDL-C, and cholesterol.

3.5Population preventability estimatesWe estimated adjPAFs for 32 modifiable risk factors. For HCC, GGT contributed the highest adjPAF (57.7 %, 95 % CI: 48.0–67.4 %), followed by other biochemical and clinical markers. Category-level estimates showed that clinical biomarkers accounted for the largest preventable burden (76.4 %, 95 % CI: 65.6–87.2 %), followed by chronic digestive diseases (59.9 %) and anthropometric traits (45.6 %) (Fig. 4A–B). In total, 83.3 % (95 % CI: 74.7–93.3 %) of HCC cases could be attributed to modifiable factors. The proportion of preventable cases was greater in males (87.5 % vs 76.3 %), individuals aged ≥ 60 years (87.9 % vs 72.9 %), HCC cases diagnosed within 5 years of follow-up (85.5 % vs 77.9 %), and those with high genetic risk levels (86.4 % vs 70.7 %) compared to their respective counterparts.

Population preventability of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA). A, the adjusted population attributable fraction (adjPAF) of modifiable risk factors for HCC. All risk factors were assessed independently to ensure that each was considered in isolation. B, the joint average sequential PAF of modifiable risk factor categories for HCC. C, the adjusted population attributable fraction (adjPAF) of modifiable risk factors for iCCA. All risk factors were assessed independently to ensure that each was considered in isolation. D, the joint average sequential PAF of modifiable risk factor categories for iCCA.

In contrast, 37.7 % (95 % CI: 21.3–52.4 %) of iCCA cases were attributable to modifiable factors. GGT (21.2 %) and smoking (14.1 %) were the leading contributors. Category-level preventability was highest for clinical biomarkers (32.5 %) and lifestyle/demographic factors (16.5 %) (Fig. 4C–D). The proportion of preventable cases was similar across subgroups defined by sex (38.1 % vs 37.1 %), age (35.9 % vs 36.2 %), follow-up duration of iCCA cases (32.2 % vs 33.2 %), and genetic risk levels (34.4 % vs 32.6 %).

In sensitivity analyses that excluded surrogate hepatic biomarkers such as ALT, AST, GGT, IGF-1, the adjPAF of modifiable factors declined to 50.8 % (95 % CI 43.8–57.7 %) for HCC and 22.9 % (95 % CI 11.3–34.8 %) for iCCA.

4DiscussionThis study provides a comprehensive comparison of HCC and iCCA across global incidence patterns, risk factor profiles, causal inference, and population preventability. We identified 42 modifiable risk factors for HCC and 8 for iCCA, with preventable proportions estimated at 83.3 % and 37.7 %, respectively. These findings underscore the markedly greater potential for HCC prevention compared to iCCA.

The moderate correlation between HCC and iCCA incidence across countries suggests shared etiological components, likely involving common environmental or metabolic exposures [18]. However, the far greater variability in HCC incidence reflects the influence of highly region-specific factors such as HBV infection. For example, HCC incidence rate is high in China, which may largely ascribe to the relatively high prevalence of HBV infection [19]. The persistent reduction in HBV infection rate during the last decades have driven a significant decline in HCC incidence in this country, whereas the iCCA incidence remained stable in the same period [20]. Notably, the higher incidence of iCCA over HCC in specific countries (e.g., Algeria) suggests unique regional risk factors or genetic predispositions that warrant further investigation. However, the incidence rates of both iCCA and HCC in these countries are extremely low (∼1/100,000), which may introduce uncertainty into the cancer registry data. Despite stringent criteria to exclude registries with over 30 % unspecified liver cancer cases, variability in data quality, especially in regions with less developed healthcare infrastructure, may have led to underreporting or misclassification, affecting HCC/iCCA incidence rates. This could explain surprising findings, such as lower reported HCC incidence in some African countries compared to European countries, and should be considered when interpreting the results.

One notable observation in our study is the nearly equal number of iCCA and HCC cases identified in the UKBB cohort, which contrasts with the UK cancer registry data where HCC typically has a higher incidence (2.80/100,000 vs 1.73/100,000). While we confirmed the accurate application of diagnostic codes, the unique characteristics of the UKBB participants, such as aged 40–70 years, might have led to an overrepresentation of iCCA cases. This highlights the need for caution when generalizing our findings and suggests that future studies should validate these results using more representative cohorts.

The identification of 44 risk factors for HCC highlights its multifactorial nature [21,22]. Many well-established exposures, such as liver cirrhosis, liver enzymes and testosterone were confirmed [23,24]. Additionally, we identified underexplored associations, including those with blood traits and biochemical markers like reticulocyte percentage (positive) and IGF-1 (inverse). Several chronic digestive diseases (e.g., duodenitis, gastritis, PSC) were also linked to HCC risk, aligning with previous studies suggesting liver-gut crosstalk as a contributor to hepatocarcinogenesis [25,26]. PSC emerged as the strongest risk factor, but its impact differed markedly between HCC and iCCA (HR=17.35 for HCC and HR=30.79 for iCCA), which was consistent with prior studies [27]. This divergence may account for different pathophysiology [27–29]. For example, PSC‐induced chronic cholestatic inflammation and fibrosis first damage the biliary epithelium, markedly accelerating cholangiocarcinogenesis [30], while sustained inflammation and the ensuing cirrhosis further elevate the probability of HCC development [31]. Inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis were also associated with elevated HCC risk, potentially via shared inflammatory or fibrotic pathways [32,33]. While it is known that patients with inflammatory bowel disease have an increased risk of liver-related complications, such as liver cirrhosis [34], these potential links with HCC warrant further investigation, ideally using datasets with detailed clinical information.

In contrast, the smaller number of significant risk factors for iCCA highlights the need for further etiological investigation. Most HCC-associated factors were either not associated with iCCA or had weaker effects. For instance, male sex was strongly associated with HCC but not iCCA, diverging from trends seen in many other cancers [35]. This finding underscores the urgent need for more focused and intensive research efforts to identify additional specific etiological factors for iCCA, which, although less common worldwide, remains an equally significant liver cancer [36]. Nonetheless, the modifiable iCCA risk factors identified—such as smoking, BMI, and liver disease—overlapped with those for HCC, suggesting shared upstream pathways and potential for joint prevention strategies.

Subgroup analyses demonstrated consistency in the direction of associations across age, sex, genetic risk, and follow-up duration. However, the magnitude of effects varied. For instance, patients with chronic liver diseases had a 65-fold increased risk for HCC diagnosed within five years of follow-up, emphasizing the need for urgent and targeted preventive measures in at-risk individuals [37]. Stratified analysis revealed gender-specific associations with the effects on HCC and iCCA, highlighting significant gender differences in the outcomes [38–41]. However, reproductive factors such as menopausal status, number of births, and exogenous hormone use were not considered, necessitating further validation of these findings.

Observational evidence suggested that several widely prescribed agents including low-dose aspirin [42], metformin [43] were associated with a lower incidence of HCC [44]. These medications modulate metabolic circuits implicated in hepatocarcinogenesis by activating AMP-activated protein kinase, inhibiting mTOR and NF-κB signalling, enhancing insulin sensitivity, and suppressing the mevalonate–cholesterol pathway [44]. Because medication use was not analysed as an exposure in this study, the potential of these agents may have been underestimated. Future studies should incorporate detailed pharmacologic data and formally quantify drug-specific effects across diverse populations. Furthermore, metabolic risk factors—particularly hypercholesterolaemia and obesity—appear to accelerate HCC development by intensifying insulin resistance, lipotoxicity, and hepatic inflammation [44–48]. Our results support this mechanistic paradigm, strengthening the observed positive association between metabolic dysfunction and HCC risk [49–51]. By contrast, these same indicators showed no significant positive link with iCCA. Indeed, higher concentrations of LDL and total cholesterol were inversely associated with iCCA risk, suggesting divergent mechanisms [52]. Additionally, metabolism-related genetic variants and exposure may promote PLC via common metabolic disorders, underscoring the extensive influence of modifiable risk factors and their potential contribution to effective prevention [53,54].

MR analyses supported the causal roles of liver disease, ALT, GGT, and several metabolic traits in both cancers, which was consistent with previous studies [55,56]. Interestingly, higher genetically predicted LDL-C and cholesterol levels were inversely associated with HCC and iCCA risk. This pattern was consistent with observational findings and may reflect biological mechanisms such as improved hepatic fat export via VLDL or enhanced antitumor immune activity, as demonstrated in preclinical models [57,58]. These observations suggest that genetic variants facilitating the release of liver fat into the bloodstream could have beneficial effects on liver diseases and may partly explain the “protective effect” of cholesterol and LDL on liver cancer, especially HCC [59,60]. Therefore, it is premature to conclude a causal relationship between cholesterol, LDL, and both HCC and iCCA, as liver fat could be a confounding factor.

We also found genetically predicted cholelithiasis and cholecystitis were causally associated with an increased HCC risk. Chronic cholestasis promotes bile acid dysregulation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis, all considered precursors to HCC [61]. However, these conditions and indices may serve as surrogate markers of hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis and may likewise be applicable to duodenitis and gastritis, perhaps to an even greater extent. Future studies to explore the underlying pathogenesis are therefore warranted.

Our PAF analysis highlights the public health potential of addressing key modifiable exposures. For HCC, clinical biomarkers (particularly liver enzymes and hepatokines) and chronic digestive conditions accounted for the largest share of preventable risk. Many of these markers likely reflect underlying liver disease, emphasizing the value of early screening and management of hepatic dysfunction [62]. Notably, the preventable fraction was highest among males, older individuals, and those with high genetic risk—groups that may benefit most from targeted prevention programs.

In contrast, only 37.7 % of iCCA cases were attributable to modifiable risk factors. This aligns with previous studies suggesting that up to 70 % of iCCA cases occur without known exposures [63]. Although we identified several chronic digestive conditions associated with iCCA, the overall preventable burden remains modest, highlighting the challenges in developing population-wide preventive strategies. Focused research into novel iCCA risk factors and enhanced screening in high-risk groups is needed.

While our analysis focuses on modifiable risk factors and the use of PAF to estimate the preventable fraction of HCC and iCCA cases, we acknowledge the limitations of this approach [64]. Liver disease etiology is inherently complex and influenced by a multitude of interacting factors, many of which are not fully understood. The PAF estimates, while useful for public health planning, assume that risk factors can be fully eliminated—an idealized scenario that may not be feasible in practice. Moreover, the effectiveness and feasibility of interventions targeting these risk factors should be considered, as the current PAF calculations may overestimate the true potential for disease prevention. Therefore, these estimates should be interpreted with caution, recognizing the broader context of disease prevention strategies and the challenges of addressing multifactorial diseases like HCC and iCCA.

Our study, while informative, has limitations. First, the retrospective nature of cancer registry data could introduce recording biases. Misclassification issues might arise from the reliance on ICD codes for HCC and iCCA classification. Moreover, the distinction between iCCA, perihilar CCA, and distal CCA in the cancer registries is primarily based on histological subtyping, which can vary in accuracy due to differences in diagnostic practices. This variability may affect the reliability of our findings, so the results should be interpreted with caution. Second, the number of incident HCC and iCCA cases in UKBB is relatively small, which limits statistical power and the generalization. We adjusted for known confounders, but unmeasured factors may remain. For example, we lacked information on HBV viral load and other detailed virological data. Besides, lifestyle and clinical factors in UKBB were recorded at baseline and may have changed during follow-up. Third, our findings are derived from the UKBB, a single-country database that may not fully capture the global diversity of risk factors for HCC and iCCA. While our analysis identifies modifiable risk factors relevant to a Western population, it is important to acknowledge that these findings may not be applicable to other regions. For example, in Southeast Asia, parasitic infections of the biliary tract are a leading cause of iCCA [65], whereas this risk factor is absent in the UK and, therefore, not represented in our dataset. Similarly, asbestos exposure, an emerging risk factor in Western countries, was not specifically addressed in our study despite its growing significance as highlighted by recent guidelines [7]. These regional differences underscore the need for caution when generalizing our findings to non-Western populations. Finally, this observational study cannot establish causality. Residual confounding and biases inherent to non-randomized data may affect the associations we observed. We note that we cannot rule out reverse causality such as preclinical disease affecting exposures or other confounders. Future work in independent, diverse cohorts with prospective surveillance data and richer exposure information will be needed to validate and extend these findings.

5ConclusionsIn summary, our study underscores the distinct yet partially overlapping epidemiological profiles of HCC and iCCA, suggesting that HCC might be more amenable to prevention through the management of modifiable risk factors. The findings also highlight the necessity for further research into the less understood risk factors for iCCA to enhance prevention and treatment approaches. However, the limited number of HCC and iCCA cases in the UKBB restricts the external validity of the findings, necessitating replication in larger, multi-ethnic cohorts with more diverse exposure profiles in the future.

FundingWe acknowledge the Shanghai Rising-Star Program (grant number: 24QA2701000) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 82204125).

Author contributionsZL conceived the study design. TW performed statistical analysis and data visualization. MD scrutinized the statistics. TW, ZL and MD wrote the manuscript. XC and TZ supervised this study. All authors provided critical revisions of the draft and approved the submitted draft.

Data availability statementThe UK Biobank data are available from the UK Biobank upon request (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). Liver cancer incidence data are available from the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (CI5) Volume XII (https://ci5.iarc.who.int/ci5-xii).

None.