Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a double-stranded DNA virus, and a member of the Hepadnaviridae family of viruses [1]. HBV can be spread person to person through exposure to infected blood, semen and other body fluids. It is commonly transmitted vertically from mother to child perinatally but can also be transmitted horizontally through needle stick injuries, needle sharing practices and sexual contact [2]. The World Health Organization reported in 2022, that 254 million people were living with chronic HBV infection (CHB), with 1.2 million new infections occurring annually [3]. Progression to chronic HBV infection is age dependent as more than 90 % of infants, 50 % of young children (1–5 years), and 5–10 % of healthy adults (19 years and older) will develop CHB [3,4]. Although not all individuals with chronic infection will develop clinical illness, HBV is responsible for approximately 1.1 million deaths annually, primarily due to end stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [5,6].

1.2HBV lifecycle and modes of persistenceHBV has a compact 3.2kbp relaxed circular partially double stranded DNA genome (rcDNA) containing overlapping reading frames coding for six proteins [7,8]. The rcDNA is encapsulated by core protein (HBcAg), and the host-derived lipid envelope consists of large (PreS1), medium (PreS), and small (S or HBsAg) surface proteins. The non-structural proteins “X” (HBx) plays an important role in cccDNA persistence and cancer development, while the “e” antigen (HBeAg) possesses an immunomodulatory role [9,10]. The virus facilitates entry (Fig. 1) into hepatocytes by a low-affinity interaction of the viral surface protein (PreS1) with heparin sulfate proteoglycans receptor (HSPG) followed by interacting with the sodium-taurocholate-cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) bile acid receptor. Once endocytosed, the virus coat fuses with the endosome and the core particle containing the rcDNA is transported to the nucleus. In the nucleus, the rcDNA is repaired by host proteins and chromatinized to generate the covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) [8]. The cccDNA serves as the primary transcriptional template for all viral mRNAs —including the pre-genomic RNA (pgRNA) which is used as the template for production of rcDNA and mRNAs encoding viral proteins [8,11]. Within the cytoplasm, the viral core protein undergoes self-assembly together with the pgRNA and viral polymerase, forming nucleocapsids [12]. Within 90 % of nucleocapsids, viral replication (rcDNA synthesis) takes place through the reverse transcription of the pgRNA; however, in 10 % of nucleocapsids, reverse transcription results in replication incompetent double stranded linear DNA (dslDNA) synthesis. These nucleocapsids can be recycled back into the nucleus or enveloped with hepatitis B surface antigens (large, middle and small HBsAg) and released from infected hepatocytes through the multivesicular body pathway [7,13]. It is important to note that nucleocapsids containing dslDNA genomes can integrate into the host cell genome with a frequency of 1 in ∼105–106 infected cells and can contribute to HCC development [14]. Large amounts of sub-viral particles consisting of HBsAg are released from infected hepatocytes which negatively impact HBV-specific immunity [7]. The cccDNA originates from both incoming virions and the intracellular recycling of nucleocapsids [11]. This dual origin combined with its long half-life (i.e., for the life of the hepatocyte), is the reason why cccDNA concentrations experience minimal decline even after extended treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues (NA).

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) Life Cycle. A hepatitis B virion containing (rcDNA) interacts with low-affinity with heparin sulfate proteo-glycans receptor (HSPG), and then enters the nucleus of hepatocytes via the sodium-taurocholate-cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP), a bile acid receptor. Following endocytosis, the capsid containing rcDNA is transported to the nucleus, where it is repaired by host proteins and chromatinized to form the HBV covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). The cccDNA is used as the template for transcription of all viral mRNAs including the pgRNA. Once the pgRNA is exported to the cytoplasm, it associates with the viral polymerase and core proteins to create a nucleocapsid. Reverse transcription of the pgRNA can result in either rcDNA or double stranded linear DNA (dslDNA) that can be recirculated back into the nucleus or trafficked through the ER-Golgi to gain surface proteins and exit the cell. Deposition of dslDNA results in the integration of HBV (non-replicating virus) into the host DNA.

The formation of the cccDNA pool in the nucleus of the infected hepatocytes [15] creates a chronic, persistent viral reservoir which is less vulnerable to host immune system strategies attempting to clear infection leading to a state of chronic infection [16,17]. The cccDNA serves as a template for viral RNA transcription and viral replication. This ensures the continued production of viral proteins which facilitates chronic infection. In addition, HBV utilizes the reproductive machinery of the infected host cell to replicate thus ensuring a continued presence of viral DNA in daughter cells [18,19]. Therefore, permanent silencing or elimination of cccDNA is crucial to prevent risk of viral reactivation and achieving HBV a functional and sterilizing cure, respectively [11,20]. However, cccDNA is not the only obstacle to HBV elimination. Targeting integrated HBV DNA in addition to cccDNA may be necessary. Even if not replication competent, integrated HBV is also a source of HBsAg production. Furthermore, HBV DNA integration plays a key role in the development of liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Therefore, silencing or elimination of integrated HBV is required to achieve functional (i.e. clearance of HBsAg but viral template persists with risk for reactivation) and sterilizing cure (i.e. complete clearance of all viral particles), respectively. In this virology-focused review, we consider the mechanisms, detection, consequences and targeting of cccDNA and integrated HBV.

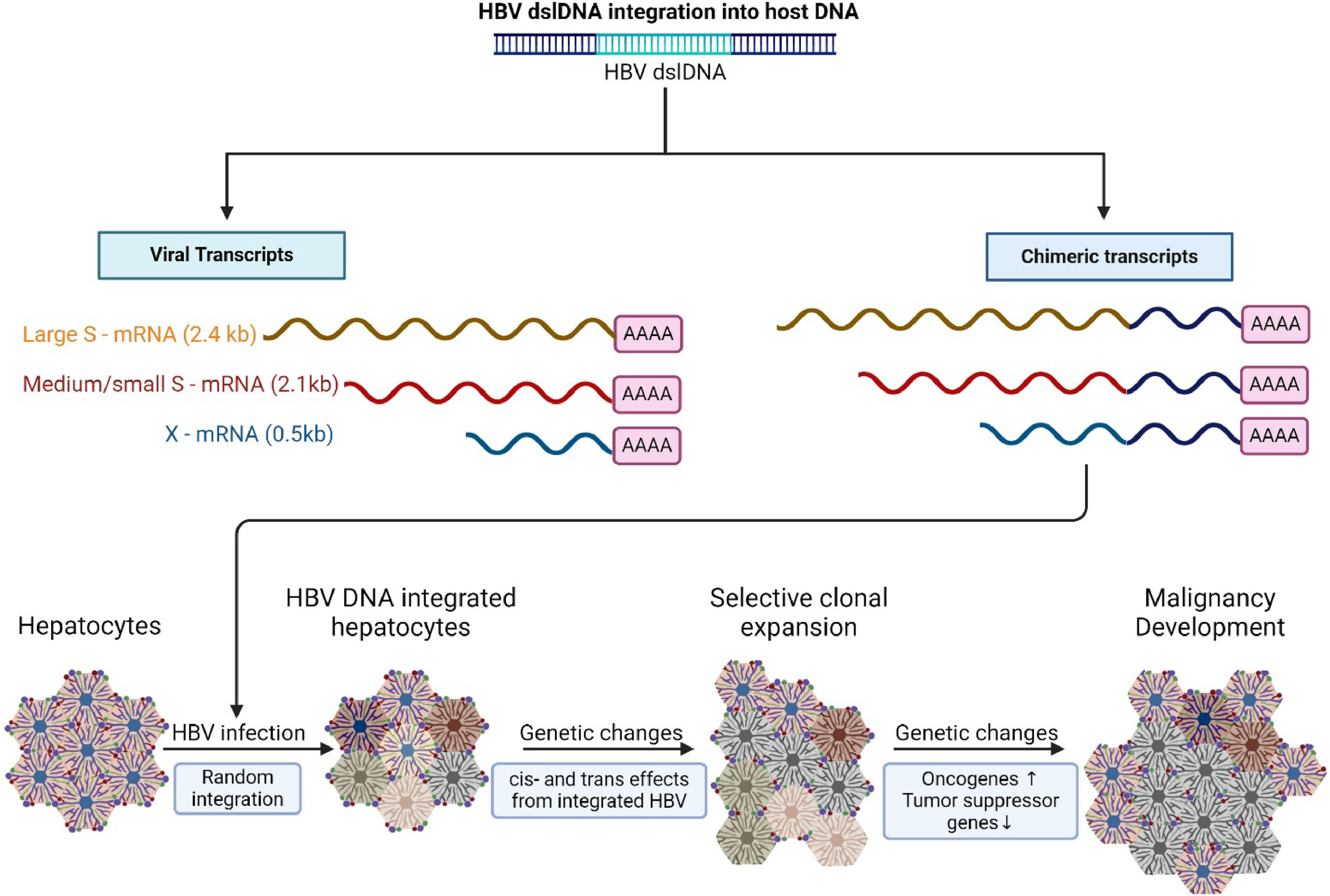

2HBV DNA integration mechanisms2.1Process of HBV DNA integration in the host genomeHBV DNA integration is a complex process influenced by viral and host factors (Fig. 2). As discussed, the cccDNA pool serves as the transcriptional template for viral mRNAs and pgRNA. The HBV pgRNA is then subsequently reverse transcribed within the newly formed nucleocapsids by a viral polymerase enzyme to yield capsids containing rcDNA. Occasionally, during genome replication, faulty primer translocation to newly synthesized minus-strand DNA results in the production of double-stranded linear DNA (dslDNA) genomes instead of rcDNA genomes, the latter which can be integrated into the host genome [13,21–23]. Targeted long-read sequencing suggests that while full-length genomes may integrate, this integrated DNA cannot support viral replication as it lacks precore and core transcripts [13]. Despite an incomplete understanding of how viral factors affect HBV DNA integration into the host, it is suspected that viral proteins including the HBV polymerase, HBV core and HBV X proteins contribute to the integration process due to their DNA binding activities [24–26]. The HBV polymerase plays a crucial role in viral reverse transcription and replication [21]. This enzyme converts pgRNA into linear DNA intermediates that are suitable for integration. Furthermore, the HBV X protein enhances HBV replication by stimulating gene expression from the cccDNA template. This protein interacts with host cellular factors involved in DNA repair pathways, such as the DDB1 (Damaged DNA Binding protein 1), promoting the integration of viral DNA into the host cellular genome. Various host factors play roles in mediating HBV DNA integration. HBV utilizes host DNA repair machinery to facilitate the integration process. As an example, the virus manipulates the non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway. Specific components of the NHEJ pathway, which is responsible for repairing double-stranded DNA breaks, such as the Ku70/Ku80 and XRCC4 proteins, are involved in ligating the viral DNA into the host cellular genome [27]. The majority of virus-cell junctions exhibit minimal or no sequence homology with cellular DNA suggesting they likely utilize the classical NHEJ pathway [28,29]. Additionally, chromatin structure influences HBV DNA integration, as it interacts with the entire host genome, showing a preference for active chromatin regions [30]. These active chromatin regions can be detected via active histone marks such as H3K4me3, H3K4me2, and H3K27ac.

Outcomes of HBV dslDNA integration into host DNA within hepatocytes. Random integration of dslDNA can result in not only viral transcription of large (preS1), medium (PreS2), small (HBsAg), and HBx proteins; but can also create chimeric transcripts with host derived DNA. Integration of dslDNA contains strong promoters which can result in the transcription of proto-oncogenes which can cause changes in cell physiology. Over-time, as infection progresses, integration events and damage caused by the immune system can lead to genome instability and clonal expansion of hepatocytes leading to cancer development.

In addition to active chromatin regions, HBV preferentially exploits other fragile sites in the genome. For example, sites in the genome that contain double-strand DNA breaks are susceptible to the HBV DNA integration process [31]. Cytosine phosphoguanine (CpG) islands, characterized by a high density of CpG dinucleotide repeats, are favored sites for HBV DNA integration into the cellular genome of hepatocytes [31]. The dinucleotide repeats that make these CpG islands increase susceptible to viral integration. Telomeres are regions of repetitive DNA sequences at the end of a chromosome responsible for maintaining the genomic stability of the chromosomes and protecting them from degradation and fusion events [28,32,33]. Telomeres serve as HBV DNA integration sites. During chronic liver injury, there is increased cell turnover, which accelerates telomere shortening, leading to chromosomal instability and cell senescence or apoptosis, which can drive carcinogenesis [28]. HBV integration events have been reported to be enriched in the proximity of telomeres in DNA within HCC compared to paired non-tumor tissue. Moreover, human repetitive regions such as long interspersed nuclear elements (LINE), short interspersed nuclear elements (SINE) and simple repeats (microsatellites) are favored sites for HBV DNA integration. HBV DNA integration can lead to deleterious consequences for the host cell function including viral persistence, oncogenesis, altered host signaling pathways and altered gene expression.

2.3Knowledge gaps related to HBV DNA integrationDespite recent advancements in our knowledge of HBV integration many areas require further understanding. Further development of small animal and cell culture models that recapitulate the HBV lifecycle and natural history accurately are required [28]. The mechanism and timing of HBV DNA integration during infection are unclear; whether integration is an early event, continues throughout chronic infection or reaches a stable equilibrium remains to be clarified. Moreover, the specific cellular pathways involved in HBV DNA integration remain unidentified, along with the role of other cellular proteins that may be pivotal in this process. There is a lack of clarity regarding viral factors influencing integration such as the potential involvement of viral proteins in the integration process. Addressing these knowledge gaps is key to advancing our understanding of HBV pathogenesis and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

3HBV infection persistence3.1cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA contribute to persistent viral antigen and host immune escapeThe formation of the cccDNA pool establishes persistent viral infection with continuous production of viral proteins. Although integrated HBV DNA can result in persistent HBsAg expression, integration of HBV DNA itself is not replicable due to the structure of the integrated dslDNA [31,34,35]. Integrated viral DNA is not a source of the viral polymerase, HBeAg and HBsAg since the integration event separates the promoter regions of these viral proteins from the coding region [36]. In contrast, HBV integrations usually retain all the viral promoter and coding regions needed for HBsAg-encoding transcripts. However, due to the nature of the integration, these transcripts bypass the polyadenylation (polyA) site), resulting in hybrid mRNAs that incorporate host genomic sequences. Therefore, since the polyadenylation signal is required for the optimal production of HBsAg, HBV DNA integrations are less capable of producing HBsAg compared to cccDNA. Despite this, integrated DNA still serves as an important source of HBsAg expression. cccDNA serves as the primary source in HBeAg-positive individuals whereas integrated HBV DNA is the main source of HBsAg in HBeAg-negative patients. With viral integration, the omnipresence of HBV in the host genome enables escape from innate immunity recognition [37]. Several strategies are utilized by the virus. HBV replication occurs using a transcriptional template that resembles host chromatin structure. This process produces new virus particles which are protected by viral capsids. This protection occurs since human hepatocytes lack or have inactive DNA sensing pathways. HBV evades the host immune system by promoting a defective antiviral adaptive immune response. Despite effective T cell responses in acutely infected HBV patients, the CD4 and CD8 T cell responses in chronic HBV are suboptimal [38,39]. With chronic infection, anti-HBs levels are generally undetectable. Furthermore, the HBV DNA polymerase can inhibit the translocation of the Poly-ADP Ribose Polymerase 1 (PARP1), an enzyme involved in the repair of chromosomal DNA [37]. The inhibition of this enzyme results in the upregulation of the expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells at the transcriptional level [37]. The upregulation of this ligand results in increased interaction with the PD-1 on the surface of T cells. This interaction leads to T cell inhibition. This immunosuppression leads to disease progression and promotes the development of HCC. HBV can inactivate innate immune system components, such as dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and natural killer T-like cells [40–42]. By affecting the innate immune system, this compromises adaptive immunity quality hence ensuring a blunted immune response.

3.2Role of cccDNA in viral latency and reactivationEstablishment and replenishment of cccDNA contributes to viral latency. It is estimated that approximately 2 billion people have been exposed to the HBV, and despite clearance of serum HBsAg, may develop occult hepatitis B with persistence of replication competent cccDNA and integrated viral genomes and low level HBV DNA in serum and liver [43,44]. This latent or occult HBV infection can reactivate with the use of immunosuppressive therapies (i.e., especially therapies which affect B cell immune function and the suppression of anti-HBV immunity [45–47,45,48]. The phenomenon of HBV reactivation highlights the challenges to achieving functional and sterilizing cure. Achieving permanent silencing or elimination of cccDNA is crucial to prevent HBV reactivation and to goals of achieving cure [11].

4Diagnostic methods for detecting cccDNA and integtated HBV DNATo better understand the pathophysiology of HBV and develop therapeutic strategies targeting cccDNA and integrated HBV, it is critical that these targets and their products can be identified, quantified and discerned from one another. Southern blotting and quantitative (qPCR) are established methods for detecting HBV cccDNA [49,50]. Droplet-Digital PCR (ddPCR) can detect and quantify trace amounts of cccDNA which persist in the nucleus of infected hepatocytes post antiviral therapy. PCR strategies used for integrated HBV DNA detection include Alu-PCR and inverse-nested PCR (inv-PCR) [51]. Alu-PCR is a DNA fingerprinting method intended to target Alu elements. Inverse PCR is an alternative method utilized for amplifying the unidentified cellular DNA neighboring an integrated sequence [52,53]. Next-Generation-Sequencing (NGS) and Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) technologies enable rapid sequencing of large amounts of DNA or RNA and are also employed for detecting HBV DNA integration [54,55,57,58,56].

Distinguishing between HBV DNA derived from cccDNA and integration sites poses challenges in HBV research. The HBV dslDNA, which lacks the DR1-PAS region (the area between direct repeat 1 (DR1) and the polyadenylation signal (PAS)), is suspected to be the precursor for HBV integration. Most HBV DNA integrations occur at the DR1 locus, hence disrupting the DR1-PAS region. Consequently, these integrated HBV transcripts exhibit a significant drop in RNA coverage within the DR1-PAS region [59]. As cccDNA transcripts all employ a shared 3’ polyadenylation signal, the DR1-PAS region mainly represents the transcriptional output of cccDNA. Thus, any transcriptional activity associated with the DR1 PAS region originates primarily from the cccDNA template [60]. This ability to discern between cccDNA and integrated DNA is critical for evaluating the residual risks of HBV infection progression, HCC development, as well as viral relapse following HBsAg clearance [59]. It is also key for interpreting response to current and future HBV treatment strategies.

5Clinical Implications5.1Challenges of targeting cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA for therapeutic interventionTargeting cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA for therapeutic intervention brings multiple challenges. The stability and persistence of integrated HBV DNA in the hepatocytes of infected individuals is a key obstacle. Achieving specificity for viral targets and ensuring efficient and safe delivery of gene silencing and editing agents to eliminate cccDNA pools and integration sites from all infected hepatocytes are primary challenges. The diverse locations of integrated HBV DNA into the host creates challenges to develop therapies that can target the viral DNA at a multitude of insertion sites [31].

Current therapies based on nucleos(t)ide analogues (NA) and pegylated interferon alpha (IFN) can suppress HBV replication and reduce the risk of complications including cirrhosis and HCC but do not completely eliminated HBV [61] (Table 1). IFN therapy is capable of regulating the transcription of cccDNA. Treatment with IFN therapy increases expression of the Interferon Induced Protein with Tetratricopeptide Repeats 1 (IFIT1) gene resulting in reduced levels of K4 methylation, K27 acetylation and K122 acetylation on histone H3 [62]. These modifications inhibit the transcription of cccDNA. Additionally, epigenetic modifications induced by IFN on cccDNA can lead to the repression of HBV. The transcriptional activity of cccDNA is sustained by histone H3K79 succinylation on the minichromosome. IFN-alpha inhibits the histone acetyltransferase General Control Non-repressed 5 (GCN5) which possesses succinyltransferase activity. This inhibition reduces the succinylation of H3K79 leading to cccDNA clearance. IFN therapy can inhibit integration site HBV replication and reducing the number of integration events within the host genome [63]. Unfortunately, IFN therapy has a relatively low success rate and requires long-duration use which can be challenging due to an unfavorable tolerability profile [3,64]. Nucleos(t)ide analogs (NA) including tenofovir, entecavir and lamivudine inhibit HBV DNA polymerase activity thereby suppressing viral replication [65,66]. Introducing NA therapy early may represent a strategy for reducing HCC risk by limiting viral integration as well as by inhibiting liver fibrosis progression [67,68]. Diminishing replenishment of cccDNA pools with sustained NA treatment may also contribute to strategies aiming to achieve functional cure.

HBV drug class effect on cccDNA and integrated DNA.

Immune modules – Check point inhibitors, toll-like receptor agonists, vaccine strategies.

cccDNA, Covalently Closed Circular DNA; CRISPR, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; Cas9, CRISPR-associated Protein 9; HBV, Hepatitis B Virus; NA, Not Applicable; RNA, Ribonucleic Acid.

Combination multimodality therapies are currently considered to represent a leading strategy to achieving chronic hepatitis B functional cure (i.e permanent HBsAg clearance from serum) (Table 1). This approach includes nucleos(t)ides, other antiviral targeting agents and immune modulating agents [69]. Achieving a functional cure is anticipated to reduce the risk for HCC, prevent liver fibrosis progression and potentially reduce liver fibrosis and improve function in those with cirrhotic liver disease [70,71].

Multiple viral and host targeting molecules are in preclinical and clinical development. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) therapies have demonstrated promise by inhibiting viral replication [48,72]. Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASO) degrade HBV mRNA using the cellular RNase H pathway and can produce HBsAg reductions sufficient to achieve functional cure [73,74]. Bepirovirsen, an ASO targeting all HBV mRNAs including HBV mRNA and pgRNA, decreases the level of viral proteins [75]. In a phase 2b clinical trial, Bepirovirsen dosed at 300 mg per week over 24 weeks led to sustained loss of HBsAg and HBV DNA in 9 % of individuals with chronic infection. Use of both siRNA and ASO may lead to diminished cccDNA replenishment.

CRISPR/Cas9 technology shows promise in HBV elimination strategies [76,77]. This modality possesses the ability to reduce viral DNA and cccDNA levels in cell cultures and animal models through targeted viral gene editing. CRISPR-Cas9 can reduce HBV cccDNA pool replenishment by hindering viral replication. Ramanan et al. [78] and Wang et al. [79] utilized CRISPR-Cas9 and RNA interference (RNAi) methods, respectively, to cleave viral DNA and suppress viral replication. In addition to HBV cccDNA, CRISPR-Cas9 technology can also target integrated HBV DNA [80]. Although the CRISPR-Cas9 system is promising, there are challenges and concerns with this strategy. The use of Cas9 to cleave integrated HBV DNA can induce harmful mutations in host DNA, potentially driving genome instability and carcinogenesis [81]. The large size of CRISPR-Cas9 genes complicates their delivery for therapeutic applications in vivo as well.

Drugs targeting specific epigenetic modifications established by viral integration, such as Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, could reverse abnormal epigenetic changes. For example, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), a HDAC inhibitor, is identified as a chemopreventive agent for patients predisposed to developing HCC [82].

In additional to the epigenomic modification actions, IFN possesses direct immune function effects which are under investigation in therapeutic combination treatment regimens focused on achieving HBV functional cure [83]. IFN activates a broad range of immune cells including T cells, macrophages, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells. These activated cells produce key immune signaling cytokines including TNF-α, IFN-γ IL-1β, and IL-6 [84]. HBV-specific CD8+ T cell are propagated within the liver resulting in cytopathic elimination of infected hepatocytes in part by surface death receptors and perforin-granzymes [85]. Non-cytopathic mechanisms directed by HBsAg-specific class I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes are activated by IFN. This enables infected hepatocytes to purge HBV replicative intermediates from the cytoplasm and cccDNA from the nucleus without being destroyed [86]. Other immunomodulatory therapies including Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, immune checkpoint inhibitors, therapeutic vaccines, and engineered T cells are all under investigation [87]. Stimulation of TLR7 in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) leads to heightened production of IFN and other cytokines, activating natural killer cells and cytotoxic T cells [88]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors aim to reverse T-cell exhaustion, thus enhancing immune responses against HBV-infected cells [89,90].

6ConclusionsThe establishment of a cccDNA pool and HBV DNA integration contribute to a persistent formation of viral proteins leading to chronic infection and negative liver-specific outcomes. Viral persistence in the host genome allows the virus to escape immune system recognition thereby contributing to disease progression. HBV DNA integration increases the risk of HCC and represents a site refractory to NA targeting therapies. Routine detection and distinguishing between cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA viral products is currently not possible in the clinical setting. DAA and IFN are useful to decrease HBV viral load, decrease the risk of liver disease and cancer, and improve clinical outcomes. However, cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA mandate the development of new strategies intended to achieve function cure. Future research efforts dedicated to fully understanding the mechanisms surrounding cccDNA and HBV DNA integration will inform the development of novel curative therapeutic approaches.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Curtis Cooper reports consulting/advisory fees from AbbVie Inc. and research-grant funding from Gilead Sciences Inc. All other authors declare no competing financial or personal interests that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Thank you to David Mackie for his contributions in editing this manuscript.