Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic autoimmune liver disease characterized by elevated aminotransferases, circulating autoantibodies, elevated immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels, and interface hepatitis with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate [1]. If left untreated, persistent hepatic inflammation leads to activation of hepatic stellate cells, fibroblast proliferation, progressive fibrosis, and eventually cirrhosis [2]. Preventing fibrosis progression – and thereby reducing mortality and the need for liver transplantation - is an important treatment goal. At initial presentation, one in three to five patients with AIH already has cirrhosis [3,4]. Despite immunosuppressive therapy, approximately 10 % of patients still develop cirrhosis within the first ten years [4]. Even among those achieving a complete biochemical response, fibrosis progression has been reported [5]. These observations emphasize the importance of liver fibrosis surveillance during treatment.

Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for staging fibrosis, but its invasiveness, risk of complications, sampling error, and intra- and interobserver variability make it unsuitable for regular monitoring [6]. Transient elastography (TE) has been validated for fibrosis assessment in AIH, but limited availability, cost, required expertise, and technical limitations in certain patients (obesity, older age, features of metabolic syndrome and ascites) restrict its use [7,8]. Although severe hepatic inflammation and cholestasis may overestimate fibrosis stage, TE is considered reliable after at least six months of treatment [9].

A reliable, non-invasive fibrosis score based on routinely available clinical and laboratory parameters, capable of reliably excluding advanced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, would be of significant additional value in AIH care. Such a score could help avoid unnecessary TE or invasive procedures and could be used in a setting where TE is not available. Several non-invasive composite fibrosis scores have been developed and validated in other liver diseases, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index (APRI), Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index, AST-to-alanine aminotransferase ALT ratio (AAR), red blood cell distribution width-to-platelet ratio (RPR) and gamma-glutamyl transferase-to-platelet ratio (GPR) [6,10,11]. These scores have shown associations with fibrosis stage at AIH diagnosis [7,12,13], but their utility during treatment remains uncertain – precisely where such scores could have the most clinical benefit.

The aim of this study was twofold. First, to evaluate the performance of existing non-invasive liver fibrosis scores for detecting advanced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in treated patients with AIH. Second, to develop and validate a new non-invasive AIH Fibrosis Score (AIHFS) based on routinely available clinical and laboratory parameters, designed to accurately identify or exclude advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis during AIH treatment.

2Patients and Methods2.1PatientsAdult patients with AIH - defined as a simplified AIH score ≥ 6 or revised original AIH score ≥ 10 [14,15] or with AIH variant syndromes [16,17] –, derivation cohort from the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) and validation cohort from the Medizinische Universität Wien (MUW), were retrospectively included if they had received at least six months of treatment, had undergone successful TE, and had routine laboratory data available within one month of TE. TE was considered successful if it included at least 10 valid measurements, < 40 % invalid measurements, and an interquartile range to the mean < 30 %. Patients were excluded if AST and/or ALT levels exceeded two times the upper limit of normal (ULN) at the time of TE or if there was evidence of decompensated liver disease, as TE results are considered unreliable under these conditions. (8, 9)

2.2MethodsTE was performed using Fibroscan® (Echosense, France) at the outpatient clinic by an experienced operator. Cut-off values for fibrosis stages F2, F3 and F4 were set at 6.3, 8.7 and 12.3 kPa, respectively, based on values derived from AIH patients in complete histological remission, which we believe most closely reflect the patients in this study [18]. Two additional studies support these cut-off values [19,20]. Advanced fibrosis was defined as ≥F3 on TE, and cirrhosis as F4 on TE.

The following non-invasive fibrosis scores were calculated using the standard formulas:

APRI= (AST (U/L)/ULN of AST(U/L))/Platelet count (109/L) X 100

FIB-4= (age (years) x AST (U/L))/((Platelet count (109/L) x ALT(U/L)1/2)

AAR= AST (U/L)/ALT (U/L)

GPR= GGT (U/L)/Platelet count (109/L)

RPR= Red blood cell distribution width ( %)/Platelet count (109/L)

Patients in the derivation cohort were recruited from the Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands (October 2014 to December 2019), and those in the validation cohort from the Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria (May 2012 and February 2020).

2.3Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21 software. Differences in patient characteristics between the derivation and validation cohorts were assessed using the Chi-square test, the Chi-square test for trend, and the Mann-Whitney U test with a p < 0.05 as the level of statistical significance.

Correlations between existing non-invasive liver fibrosis scores and liver stiffness were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. For scores that showed significant correlation with liver stiffness, diagnostic performance in detecting fibrosis stage was assessed using area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve analysis. The optimal cut-off value was determined using the Youden Index, and sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for both advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis.

Variables likely associated with liver stiffness were analyzed using univariate linear regression in the derivation cohort. Variables with significant associations (p < 0.05) were entered into a multivariate linear regression model. Coefficients of variables that remained independently associated with liver stiffness (p < 0.05) were used to create the formula for the AIHFS. The predictive accuracy of AIHFS was assessed in the same manner as the existing scores and compared to their performance in the derivation cohort. As a sensitivity analysis, this procedure was repeated in patients with AIH excluding those with variant syndromes, and with complete biochemical response, defined as normalization of AST and/or ALT. Subsequently, the AIHFS was applied to the validation cohort using the same formula derived from the derivation cohort. Diagnostic performance (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV) was calculated using the previously established cut-off value.

2.4Ethical statementAll patients provided written informed consent for the use of their data. The study was approved by the medical ethical committees of both participating centers (LUMC Medical Ethical Committee G18.068, MUW Ethik-Kommission ECS2161/2019) and was conducted in accordance with the most recent version of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its amendments.

3ResultsThe derivation cohort included 73 patients. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median time between liver biopsy at AIH diagnosis and TE was 75 months (IQR 38–121.5 months).

Baseline characteristics of the derivation and validation cohort.

Median (interquartile range), number ( %).

AIH = autoimmune hepatitis, PSC = primary sclerosing cholangitis, PBC = primary biliary cholangitis, AST = aspartate aminotransferase, ALT = alanine aminotransferase, ALP = alkaline phosphatase, GGT = γ-glutamyl transferase, IgG = Immunoglobulin G, RDW = red blood cell distribution width, E = liver stiffness.

p-values calculated using Chi-square test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate.

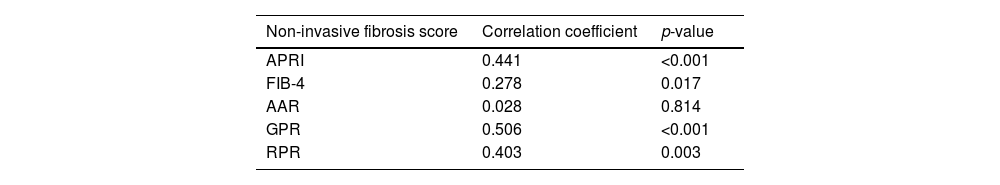

In treated patients with AIH, significant correlations between liver stiffness and APRI, FIB-4, GPR and RPR were observed. No significant correlation between AAR and liver stiffness was found (Table 2). The AUROCs of APRI, FIB-4, GPR, and RPR were statistically significant for identifying advanced fibrosis (≥F3 on TE). (Fig. 1). For detecting cirrhosis (F4 on TE), the AUROCs of APRI, GPR, and RPR were significant, whereas the AUROC of FIB-4 was not (Fig. 2).

Correlation between existing non-invasive fibrosis scores and liver stiffness.

| Non-invasive fibrosis score | Correlation coefficient | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| APRI | 0.441 | <0.001 |

| FIB-4 | 0.278 | 0.017 |

| AAR | 0.028 | 0.814 |

| GPR | 0.506 | <0.001 |

| RPR | 0.403 | 0.003 |

APRI = aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index, FIB-4 = Fibrosis-4 index, AAR = Aspartate aminotransferase-to-alanine aminotransferase ratio, RPR = red blood cell distribution width-to-platelet ratio, GPR = gamma-glutamyl transferase-to-platelet ratio.

p-values were calculated using Spearman’s rank correlations.

Results of the univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis in the derivation cohort are presented in Table 3. Only existing non-invasive liver fibrosis scores that were significantly associated with advanced fibrosis (≥F3 on TE) and cirrhosis (F4 on TE) during AIH treatment were included. To avoid collinearity, individual components of these scores were excluded from the analyses. In the multivariate analysis, APRI was the only existing non-invasive fibrosis score that remained independently associated with liver stiffness. Based on the regression coefficients of this model, the AIHFS was calculated using the following formula:

Patient characteristics and non-invasive liver fibrosis scores in the derivation cohort associated with liver stiffness (E, kPa).

ALP = alkaline phosphatase, IgG = Immunoglobulin G, APRI = aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index, RPR = red blood cell distribution width-to-platelet ratio, GPR = gamma-glutamyl transferase-to-platelet ratio.

AIHFS = 23.838+11.869 * APRI score – 0.461*Albumin level (g/L)

3.3Diagnostic performance of AIHFS and APRI in the derivation cohortThe AUROCs of AIHFS for detecting advanced fibrosis (≥F3 on TE) and cirrhosis (F4 on TE) are presented in Fig. 3. The optimal cut-off value for advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis was 9.3203. For advanced fibrosis this cut-off resulted in a sensitivity of 79 %, a specificity of 76 %, a PPV of 61 %, and a NPV of 88 %. For cirrhosis the sensitivity was 82 %, specificity 70 %, PPV 45 %, and NPV 93 %. For APRI the optimal cut-off value for both advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis was 0.4874. This resulted in a sensitivity of 75 %, a specificity of 78 % a PPV of 62 %, and a NPV of 86 % for advanced fibrosis. For cirrhosis, sensitivity was 82 %, specificity 73 %, PPV 48 %, and NPV of 93 %.

Additional analysis using the same cut-off values in subgroups of patients with AIH without variant syndromes (n = 55) and those with complete biochemical remission (n = 62) yielded similar results (Figs. 4, 5 and Table 4).

Performance of APRI and AIHFS in patients without AIH variant syndromes and with CBR.

APRI = aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index, AIHFS = autoimmune hepatitis fibrosis score, AIH = autoimmune hepatitis, CBR = complete biochemical response, PPV = positive predictive value, NPV = negative predictive value, TE = transient elastography.

The validation cohort included 81 patients, and baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

The AUROCs of APRI and AIHFS for detecting advanced fibrosis (≥F3 on TE) and cirrhosis (F4 on TE) in the validation cohort are shown in Figs. 1, 2 and 3. Using the cut-off value of 0.4874 for APRI, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for detecting advanced fibrosis were 52 %, 88 %, 61 % and 84 %, respectively and for cirrhosis 75 %, 87 %, 50 % and 95 %, respectively. Using the cut-off value of 9.3203 for AIHFS, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for detecting advanced fibrosis were 48 %, 85 %, 53 % and 82 %, respectively, and for cirrhosis 91 %, 70 %, 43 % and 97 %, respectively.

4DiscussionThe current study demonstrates that APRI is the only existing non-invasive fibrosis score that reliably excludes advanced fibrosis (≥F3 on TE) and cirrhosis (F4 on TE) during AIH treatment, thereby reducing the need for additional investigations. A novel AIHFS was developed and validated but did not outperform APRI.

Previous studies have examined the association between liver fibrosis stage and fibrosis scores such as APRI, FIB-4, AAR, GPR and RPR primarily in treatment-naïve or a combination of treatment-naïve and treated patients. However, none specifically focused on treated patients only [7,12,13]. In our derivation cohort, APRI, FIB-4, RPR, and GPR significantly correlated with liver stiffness, but AAR did not. Based on the AUROCs, APRI, FIB-4, RPR, and GPR were significantly associated with advanced fibrosis and APRI, RPR, and GPR with cirrhosis. These AUROCs were consistent with those reported in previous studies and one meta-analysis [7,21–23]. In the current multivariate analysis, APRI was the only existing non-invasive fibrosis score independently associated with liver stiffness, indicating that APRI is the most suitable existing score for fibrosis monitoring during AIH treatment.

A novel non-invasive score, the AIHFS, was developed by combining APRI with albumin, as albumin was also independently associated with liver stiffness. Both scores were validated for detection or exclusion of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis during AIH treatment. The AIHFS showed good performance but did not outperform APRI.

Notably, in both the derivation and the validation cohort, APRI demonstrated a high NPV for advanced fibrosis (86 % and 84 %, respectively) and cirrhosis (93 % and 95 %, respectively). These values were higher than those reported in a published nomogram (73 %) for advanced fibrosis [24].

These findings support APRI’s utility in ruling out advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis in treated AIH patients, preventing the need for additional diagnostics such as TE, magnetic resonance elastography or liver biopsy when APRI < 0.4874. However, due to its low PPV, an APRI score > 0.4874 should prompt further investigation. Applying this threshold, 40 % of patients in the derivation cohort and 22 % of patients in the validation cohort would warrant additional evaluation. False negative rates for APRI were acceptably low: 8 % and 12 % for advanced fibrosis and 4 % for cirrhosis in both cohorts.

APRI is based on routine laboratory parameters, making it a non-invasive, cost-effective and widely applicable tool in daily clinical practice.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The derivation cohort consists of a relatively small sample size (n = 73); however, findings were validated in an independent cohort of 81 patients with this rare liver disease. Inclusion of patients with both AIH and variant syndromes may have introduced heterogeneity, as did inclusion of patients with complete biochemical response and AST/ALT above the ULN but < 2x ULN. Nevertheless, subgroup analyses showed similar results. TE was used as the reference standard, while liver biopsy or magnetic resonance elastography may have been more ideal. However, these alternatives are less feasible, due to costs, limited availability, invasiveness, risk of complications and risk of sampling error. Patients with excessive liver inflammation (AST/ALT > 2x ULN) – as seen during the first six months of treatment or during disease relapse - were excluded [9]. Therefore, these findings are not generalizable to these clinical scenarios.

We focused on readily available parameters; therefore, known fibrosis-related markers and scores such as circulating levels of hyaluronic acid, type III procollagen, laminin, type IV collagen and ELF score were not evaluated [6]. These may be more indicative of fibrogenesis than the existing fibrosis and may be of interest in future prospective AIH studies, especially as their accessibility improves.

5ConclusionsAPRI is the only existing non-invasive liver fibrosis score significantly associated with liver stiffness in treated patients with AIH. The newly developed AIHFS did not outperform APRI. Due to the excellent NPV and reliance on easily available parameters, APRI is particularly useful for ruling out advanced fibrosis (≥F3 on TE) or cirrhosis (F4 on TE) during AIH treatment. An APRI > 0.4874 should prompt further diagnostic assessment. Further external validation in a larger cohort is recommended.

Author contributionsMartine A.M.C. Baven-Pronk: concept, design, analyzing and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, drafting the manuscript; Camiel J.M. Marijnissen: concept, design, data collection, analyzing and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript; Maaike Biewenga: concept, design, critical revision of the manuscript; Albert F. Stättermayer: providing data, critical revision of the manuscript; Maarten E. Tushuizen: providing data, critical revision of the manuscript; Bart van Hoek: study concept and design, study supervision, critical revision of the manuscript.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability: The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

None.