Among the histological components of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), the extent of fibrosis is the strongest predictor of mortality [1–4]. Accordingly, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidance identifies those with ‘at-risk’ MASH, defined by the presence of stage 2 fibrosis or greater, as the population most likely to benefit from intervention [5]. Despite significant drug development efforts, most investigational treatments have shown variable and/or modest anti-fibrotic effects in at-risk MASH, which may suggest diverse phenotypes within the patient population impede a one-size-fits-all strategy [6]. Addressing this diversity is an important area of investigation involving development of predictive markers of treatment response, omics technologies to profile molecular features of disease, and an appreciation for the potential of combination therapies to target multiple pathogenic pathways.

In addition to metabolic alterations, variations in multiple genes have been shown to predispose to disease progression in MASH [7]. Among them, the best validated association is with a common missense variant in PNPLA3 (I148M), encoding patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 protein, which is associated with an increased risk of MASH and cirrhosis [8,9]. A further missense variant in TM6SF2, encoding transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2, is associated with plasma lipid traits and disease susceptibility to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [10].

Mutations in the SERPINA1 gene coding for alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) can lead to proteotoxic liver injury, and homozygosity for the most common severe deficiency allele termed Z (protease inhibitor [Pi]ZZ genotype) confers a strong susceptibility to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [11,12]. The clinical significance of carriage of a single Z allele is less clear [13]. Observational studies have reported excess risk of liver events in MASH patients with a PiMZ genotype [14–16] but were limited in their scope by either small sample size, selection bias, or lack of adjustment for conventional risk factors in reported risk estimates. The aim of this study was to investigate whether carriage of a SERPINA1 Z mutation is independently associated with disease progression in MASLD and to compare any strength of association with both conventional risk factors and established gene variants associated with progression.

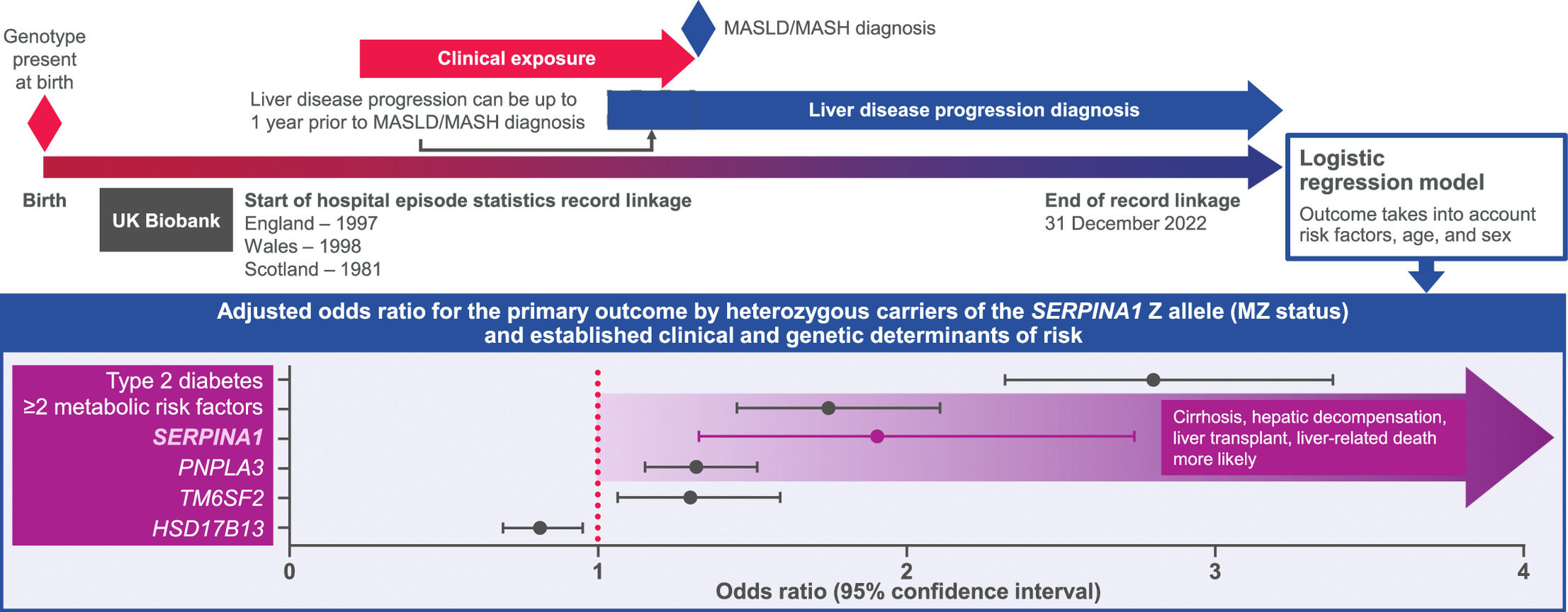

2Patients and Methods2.1PopulationThis case-control study used UK Biobank (UKB) data from a population-based prospective cohort of >500,000 predominantly healthy adults (recruited age 40–69) in England, Wales, and Scotland. Participants underwent a baseline assessment at UKB centres between 2006 and 2010, where they completed questionnaires on health-related behaviours and demographics. A research nurse took a medical history that included a self-report of medical diagnoses. In addition, most participants in UKB have linkage to longitudinal electronic healthcare records (EHRs) from primary and secondary care. Linkage dates differ by country, dating back to 1997 for England, 1998 for Wales, and 1981 for Scotland. Primary and secondary diagnoses as well as operation codes are available for each attendance.

Given known variation in Z allele by genetic ancestry, we subset to individuals of European ancestry to reduce environmental confounding (Supplementary Methods). We defined cases with a primary or secondary care diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10]: K76.0; read v2 or Clinical Terms Version 3 [CTV3]: J61y1) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH; ICD-10: K75.8; read v2: J61y8; CTV3: XaQIT) [17,18]. Supplementary Table 1 outlines the number of participants who received a code that formed these definitions. With the exception of NAFLD/NASH code descriptions, which are retained in this report for accuracy, we will adhere to the new nomenclature of MASLD/MASH given the reported minimal discrepancy between the terms [19], acknowledging that many referenced studies have used NAFLD/NASH.

To avoid misclassification bias, we excluded participants with alternative aetiologies of chronic liver disease using a combination of secondary care and self-reported data (fields 20,002 and 20,003 for diagnoses and medications, respectively). A record of any of the following codes resulted in the participant being excluded from the analyses: alcohol dependency (ICD-10: F10 or K70; self-report: 1408 or 1604); viral hepatitis (ICD-10: B15–B19; self-report: 1155, 1156, 1157, 1578, 1579, 1580, 1581, or 1582); HIV (ICD-10: B20–B24; self-report: 1439); Wilson’s disease (ICD-10: E83.0), and hereditary haemochromatosis (ICD-10: E83.1). The approach used to define liver diseases, exposures, and outcomes followed expert consensus guidelines for EHR studies [17,18].

2.2Definitions of exposures and outcomesA composite primary outcome of advanced liver disease defined as incident cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, liver transplant, or liver-related death was pre-specified to evaluate the risk of disease progression with greater sensitivity. In brief, compensated cirrhosis was defined using ICD-10 codes K74.6 (unspecified cirrhosis), I85.9 (oesophageal varices without bleeding), I98.2 (oesophageal varices in disease classified elsewhere), or I86.4 (gastric varices). Hepatic decompensation was defined by R18 (ascites), I85.0 (oesophageal varices with bleeding), I98.3 (oesophageal varices with bleeding in disease classified elsewhere), K76.6 (portal hypertension), or K76.7 (hepatorenal syndrome). Finally, liver transplant was defined using Classification of Interventions and Procedures version 4 (OPCS4) codes J01.1 to J01.3, J01.5, J01.8, J01.9, or the ICD-10 code Z94.4. The ICD code with the earliest date was taken to represent the incidence date of the composite primary outcome.

Information about cause-specific mortality was obtained through the established linkage with the UK Office for National Statistics. Liver-related mortality was defined when a death was preceded by or cause of death was recorded as compensated cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, liver transplant, liver cell carcinoma, hepatic failure, portal vein thrombosis, hepatic sclerosis, or fibrosis (Supplementary Methods).

Definitions of clinical exposures were only reported if present prior to the first diagnostic code for NAFLD/NASH. Type 2 diabetes (ICD-10 codes E11) was tested as an independent risk factor alongside a composite variable of the presence of ≥2 metabolic risk factors (obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and type 2 diabetes). We evaluated the effects of the Z allele in SERPINA1 (E342K), the common missense variants within PNPLA3 (I148M) and TM6SF2 (E167K), and a protective variant within HSD17B13 (rs28929474, rs738409, rs58542926, and rs9992651 were used to identify the single nucleotide polymorphisms, respectively). To increase confidence in the genotype calling of the PiMM and PiMZ genotypes, we used the whole exome sequence data to characterize and exclude the rare variation found in SERPINA1 (Supplementary Methods).

2.3Statistical analysesBaseline values reflect those measured during UKB recruitment, and the index reflects the date of MASLD/MASH diagnosis. We compared index characteristics between individuals who experienced the primary outcome and those who did not using the χ² test for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables (P-values are two-sided). Logistic regression was used to calculate associations for all risk factors tested on liver disease progression phenotypes. MM is the reference genotype when testing for association with MZ. All logistic regressions were adjusted for age at baseline and sex. For all tests, complete case analyses were employed. Benjamini-Hochberg correction of the false discovery rate was used to account for multiple testing [20]. Incidence rates for the primary outcome were calculated as the number of events divided by the total person-years of follow-up and expressed as the number per 1000 person-years. Follow-up begins at the index date and finishes at first recorded date of the primary outcome or the end of record linkage (31 December 2022). We evaluated the distribution of age at onset for each component of the composite primary outcome. A series of sensitivity analyses were performed to explore any potential biases in the data, including a comparison of follow-up duration between progressors to advanced liver disease vs non-progressors as well as participants with the PiMZ genotype vs PiMM genotype (Supplementary Methods). Given the strong association of type 2 diabetes with progression to advanced liver disease, we tested to see to what extent our genetic associations with liver disease progression were driven through confounding with this risk factor. Statistical analyses were done using R software version v4.2.1.

2.4Ethics approvalThis research was undertaken under UKB’s existing ethical approval (Research Ethics Committee approval 11/NW/0382; North West Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee) and project number 41,232. All research was conducted in accordance with both the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul, and consent was given in writing by all participants.

3ResultsA total of 6319 individuals with MASLD/MASH of European ancestry were identified after excluding people with an alternative aetiology of liver disease prior to diagnosis (Fig. 1). The composite primary outcome was recorded in 499 individuals during 38,422 person-years of follow-up. The prevalence of the PiMZ genotype was 3.7 % in the UKB population without liver disease. Among those with MASLD/MASH, 3.9 % of individuals who did not experience the primary outcome and 7.6 % of those who did had a PiMZ genotype. Index characteristics of the MASLD/MASH population at diagnosis and the UKB participants of European descent without prevalent liver disease are shown in Table 1. Compared to MASLD/MASH individuals without, those who experienced a primary outcome had a less favourable metabolic risk profile with higher prevalence of obesity, dyslipidaemia, and hypertension (Table 1; all P < 0.005). A comparison of the index characteristics of individuals with a MASLD diagnosis recorded in the primary care setting vs those recorded in a secondary care setting are shown in Supplementary Table 2a and 2b. A total of 1275 and 5405 MASLD cases were identified using primary and secondary care, respectively. Progression to the composite primary outcome was higher among secondary care cases compared to those diagnosed in primary care (8.70 % vs 5.10 %), possibly reflecting the increased prevalence of advanced fibrosis in a specialty care setting. The metabolic risk profile of secondary care diagnoses was also less favourable than those recorded in primary care.

CONSORT diagram.

Index characteristics of study population by incident disease progression (primary outcome) status.

| No liver disease(N = 390,650) * | MASLD/MASH | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without disease progression(N = 5820) | With disease progression(N = 499) | ||

| Age | NA | 64.85 ± 9.36 ‡ | 66.73 ± 8.18 |

| Sex | F = 54.5 %; M = 45.5 % | F = 54.6 %; M = 45.4 % ‡ | F = 43.9 %; M = 56.1 % |

| Obesity | 7.35 % † | 20.70 % ‡ | 27.86 % |

| Dyslipidaemia | 15.57 % † | 27.44 % ‡ | 33.27 % |

| Hypertension | 30.81 % † | 50.17 % ‡ | 63.93 % |

| COPD | 4.79 % † | 8.54 % ‡ | 12.22 % |

| Smoking status ⁎⁎ | |||

| Never smoker | 55.01 % † | 46.87 % | 42.89 % |

| Never smoker with COPD ⁎⁎⁎ | 1.62 % † | 3.00 % ‡ | 7.01 % |

| Previous smoker | 34.96 % † | 40.36 % ‡ | 45.29 % |

| Previous smoker with COPD ⁎⁎⁎ | 6.51 % † | 10.90 % | 12.83 % |

| Current smoker | 9.68 % † | 12.34 % | 11.42 % |

| Current smoker with COPD ⁎⁎⁎ | 16.39 % † | 21.45 % | 29.82 % |

| Type 2 diabetes | 7.33 % † | 22.97 % ‡ | 47.29 % |

| ≥2 metabolic risk factors ⁎⁎⁎⁎ | 16.89 % † | 37.53 % ‡ | 53.51 % |

| Z carriers (PiMZ) | 3.74 % | 3.89 % ‡ | 7.63 % |

| PNPLA3 (I148M) het/hom | 33.72 %/4.62 % † | 38.16 %/8.09 % ‡ | 41.16 %/12.45 % |

| TM6SF2 (E167K) het/hom | 13.90 %/0.54 % † | 17.65 %/0.79 % ‡ | 18.07 %/3.21 % |

| HSD17B13 het/hom ⁎⁎⁎⁎⁎ | 38.56 %/6.85 % | 37.43 %/6.71 % ‡ | 33.06 %/5.31 % |

All continuous variables are summarized using mean and standard deviation. Index defined as date of MASLD/MASH diagnosis. Disease progression defined by whether an individual experienced the primary outcome (incident cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, liver transplant, or liver-related death).

Defined as participants without any diagnosis of MASLD/MASH, cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, liver transplant, or liver-related death. The same exclusion criteria for liver disease due to other causes were also employed in this group. As it was not possible to measure an index date, prevalence of metabolic risk factors was calculated using the full length of secondary care data.

Proportions of smoking status within columns do not total to 100 % due to a subset of participants preferring not to answer or variable missingness.

Smoking status was defined as never, previous, and current at baseline (variable ID 20,116). The percentages reported reflect the prevalence of COPD within each category of smoking (eg, number of COPD participants who never smoke/total number of never smokers). Total COPD prevalence is therefore a weighted average of these estimates, with the weights equalling the proportion of the total sample endorsing a smoking category. These percentages are reported to demonstrate the increased rates of COPD among smokers and the impact of liver disease progression in each category of smoking.

Significantly different between individuals with MASLD/MASH without disease progression and those without liver disease (P < 0.05).

Significantly different between progressors of MASLD/MASH (P < 0.05).

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; F, female; het, heterozygote; hom, homozygote; M, male; MASH, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; NA, not available; Pi, protease inhibitor.

Fig. 2 shows the relationship between metabolic and genetic risk factors and the composite primary outcome. The I148M missense variant in PNPLA3, E167K missense variant in TM6SF2, MZ variant in SERPINA1, type 2 diabetes, and presence of 2 or more metabolic risk factors were all significantly associated with the primary outcome after correction for multiple testing, whereas a common variant in the HSD17B13 gene was shown to have a protective effect. No differences in associations were found when comparing the SERPINA1 MZ and ≥2 metabolic risk factors (P-value for association comparison = 0.68), TM6SF2, or PNPLA3 (P-values for both association comparisons = 0.07), suggesting risk equivalence of these variables in the present dataset. After adjustment for the presence of ≥2 metabolic risk factors, type 2 diabetes, and variants in PNPLA3, TM6SF2, and HSD17B13, the odds ratio (OR) for SERPINA1 MZ remained significant, increasing from 1.90 to 2.01 (95 % confidence interval [CI], 1.38–2.92). Unadjusted incidence rates for the primary outcome among MM and MZ individuals with MASLD/MASH were 12.79 and 22.09 per 1000 person-years, respectively.

A similar relationship was seen between MZ status and components of the primary outcome (Fig. 3). MZ status was associated with excess risk of progression to cirrhosis (OR 1.89; 95 % CI, 1.24–2.87) and hepatic decompensation (OR 1.82; 95 % CI, 1.14–2.90). The exception was liver-related death or transplant, where associations did not reach statistical significance (OR 1.31; 95 % CI, 0.76–2.27). This could be partially due to the reduced number of cases for this outcome (liver-related death or transplant = 225 [8 transplant cases]; cirrhosis = 316; hepatic decompensation = 250). Another explanation is the relative heterogeneity of this phenotype with respect to cirrhosis and hepatic decompensation. Liver-related death or transplant included all codes from cirrhosis and hepatic decompensation as well as a number of more general liver-related codes such as liver cancer or acute hepatic failure. The peak age of onset for all components of the composite primary endpoint were in the seventh decade (Supplementary Figure 1).

Adjusted odds ratios for components of the primary outcome (cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, liver-related death or transplant) by MZ status and established clinical and genetic determinants of risk.

In sensitivity analyses, we sought to understand whether follow-up time differed between progressors and non-progressors and between PiMZ and PiMM individuals. We know that MASLD/MASH is a slowly progressing disease, and it is plausible that patients with MASLD/MASH are yet to experience the composite outcome due to not having had the disease for a sufficient length of time. We therefore tested total follow-up time for each participant, censoring at death or last date of record linkage only. Total follow-up time was 2634 years for progressors and 37,344 years for non-progressors, with a mean follow-up of 5.28 years and 6.42 years, respectively (t-stat = −4.66; P = 3.97 × 10–6). The reduced follow-up found in progressors therefore suggests the likelihood of experiencing the composite outcome is not a function of follow-up time. Similarly, we compared participants with the MZ and MM genotypes for follow-up time. Total follow-up time was 1861 years and 33,725 years for MZ and MM genotypes, respectively. Mean follow-up was 7.05 years and 6.29 years, respectively (t-stat = 2.01; P = 0.04). The nominally significantly increased follow-up in MZ suggests this group had greater opportunity to progress, which may bias the OR; however, the impact of this bias may be mitigated by over 6 years of mean follow-up. We explored the impact of any variation in follow-up prior to MASLD/MASH diagnosis by subsetting to individuals with ≥12 months of observation prior to their index date. A total of 6301/6319 participants had ≥12 months of observation prior to the index diagnosis date. Supplementary Figure 2 shows the negligible impact on the ORs following the exclusion of individuals with <12 months observation prior to the index diagnosis date. The impact of prevalent type 2 diabetes on genetic associations with liver disease progression is shown in Supplementary Figure 3. ORs for genetic risk factors MZ, PNPLA3, TM6S2, and HSD17B13 showed no qualitative difference by type 2 diabetes status, and all remained significant when type 2 diabetes was incorporated into our logistic regression models (all false discovery rate-corrected P-values < 0.05).

4DiscussionIn a population cohort of individuals with MASLD or MASH, we observed an association of the SERPINA1 MZ genotype with future risk of clinical events. Carriage of the Pi*Z mutation approximately doubled the risk of progression to advanced liver disease defined as incident cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, liver transplant, or liver-related death in MASLD/MASH. Our findings suggest that the MZ genotype confers at least a similar risk of advanced liver disease as ≥2 metabolic risk factors, the presence of which increases the recommended frequency of risk assessment in the 2023 AASLD Practice Guidance [5]. Despite differences between wild-type PiMM and PiMZ MASLD patients at index in prevalence of obesity, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes, the risk associations for MZ and the primary outcome were not attenuated by adjustment for metabolic risk factors.

Our findings replicate associations of the MZ genotype with increased odds of advanced liver disease and imply at least a risk equivalent with well-established genetic variants, such as PNPLA3 and TM6SF2 [11,14,16]. In a German-Austrian cohort of biopsy-proven MASLD, Pi*Z carriers had higher odds of developing cirrhosis than carriers of common missense variants within PNPLA3 (I148M) and TM6SF2 (E167K) [14]. In that study, the MZ genotype conferred >7-fold increased odds for developing cirrhosis in adjusted analyses, a larger effect than reported in the present study. Differences in the magnitude of effect could be driven by the severity of the population in a specialty care cohort with biopsy-proven disease compared to the UKB population, which comprises a relatively healthy population sample. The precise mechanisms by which the Z variant predisposes MASLD cirrhosis are unclear, but it is plausible that the Z variant becomes an increasingly important disease modifier as the severity of MASLD increases. The misfolded Z-AAT protein causes proteotoxic stress in a dose-dependent manner. Given that AAT is an acute-phase protein that increases in expression during stress situations, the proteotoxic stress from Z-AAT is likely enhanced in liver injury related to MASLD [21]. The resultant proteotoxic stress may also impair autophagy degradation pathways that are implicated in removing toxic AAT protein from the hepatocyte, restricting a key compensatory mechanism [22–25]. Further evidence positioning the Z variant as the strongest genetic risk factor for the development of MASLD-associated cirrhosis comes from exome sequence data in the DiscovEHR human genetics study, which showed that Pi*Z carriage was associated with non-alcoholic cirrhosis with greater magnitude of effect than that observed for variants in PNPLA3 and TM6SF2 [16]. Finally, Pi*Z homozygotes are known to be at greater risk of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis than those homozygous for PNPLA3 and TM6SF2 [11].

The clinical relevance of the Pi*Z variant as a disease modifier in MASLD should prompt testing as part of the workup of MASLD. Accordingly, the 2023 AASLD Practice Guidance recommends an assessment of alpha-1 antitrypsin genotype or phenotype, but only if elevated liver chemistries are present [5]. Genetic testing in general is not recommended, as it does not alter management. Guidelines from the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) differ slightly in that they state that clinicians in specialized centres may consider the genetic risk profile for personalizing risk stratification but do not explicitly mention SERPINA1 [26]. As the European guidelines recommend, further prospective research is needed to evaluate the concept of genetic risk stratification of disease-risk progression outside the clinical trial setting. It has not been shown that adding genetic testing (which captures a currently non-modifiable susceptibility risk) to non-invasive tests is superior to non-invasive tests alone in predicting progression to advanced liver disease [27].

Therapeutic strategies to modulate the expression of pathogenic gene variants implicated in the development and progression of MASLD have shown promise in early clinical studies. In phase 1 trials, a small interfering RNA (siRNA) against PNPLA3 reduced liver fat content in individuals homozygous for the I148M variant [28]. Another study evaluated an siRNA against HSD17B13 in patients with confirmed or presumed MASH based on human genetics evidence that loss-of-function mutations are protective against MASH. Treatment resulted in reduced HSD17B13 mRNA and protein expression, with associated reductions in alanine aminotransferase [29]. These human proof-of-concept data suggest that targeting genetic pathways might be a viable treatment approach in MASLD.

Given our results show similar effects of SERPINA1 to these established variants on clinically relevant outcomes, SERPINA1 could also be a viable therapeutic target in a subpopulation of MASH. Individuals with MASH and the PiMZ genotype, with meaningful risk attributable to the latter, may benefit from the addition of a targeted therapy to reduce formation and deposition of Z-AAT polymers that are proteotoxic and known to cause progressive fibrosis. There are also potentially important implications for the conduct of clinical trials in the broader MASH population. An imbalance of Pi*Z carriers across treatment arms in interventional studies may confound interpretation of results, as their inclusion could attenuate treatment effects in histological fibrosis staging or clinical outcomes. Understanding variation in response to MASH interventions by SERPINA1 genotype, as has been done for PNPLA3 [30,31], could inform future trial populations.

Our results should be considered in the context of the following limitations. We noted an increased rate of progression to the composite outcome among MASLD/MASH cases identified through secondary care (8.7 %) vs primary care (5.1 %). Our event estimates among secondary care cases could therefore reflect the disease population with symptoms or markers of disease progression that require interacting with a specialist healthcare service. In those contexts, event rates may be higher than those derived from a primary care setting where specialist input was not sought. UKB is a volunteer-based study and is therefore not a representative population sample. The UKB is enriched for healthy individuals with lower rates of obesity and alcohol consumption relative to the broader population [32]. This participation bias is likely to result in an underestimate of liver-related clinical events given the known association between these risk factors and disease progression in MASLD. Another important limitation of the study is our reliance on diagnostic and procedural codes to define cases, non-genetic exposures, and outcomes. This limitation was mitigated through use of comprehensive code lists provided in consensus guidance that aims to harmonize and improve the generalizability of EHR-based MASLD research [17]. Furthermore, our analysis population excluded individuals with alternative aetiologies of chronic liver disease to minimize misclassification of MASLD/MASH cases. Outcomes based on ICD-10 codes contained within inpatient secondary care data only may have some degree of misclassification or underdiagnosis, which may imply a lower risk of liver-related clinical outcomes compared with cohorts with MASLD followed in clinical practice or in registry settings.

5ConclusionsCarriage of the Pi*Z mutation was found to approximately double the risk of progression to advanced liver disease in MASLD/MASH and is a risk equivalent to established metabolic and genetic risk factors for disease progression. These prognostic findings suggest that assessing the SERPINA1 genotype in patients with MASLD/MASH can not only provide information on future risk of clinical outcomes but may also have implications for the design of clinical trials.

Data availabilityThis research has been conducted using the UKB resource under Application Number 41,232. UKB data are available on application to the UKB with access fees (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk).

FundingThis work was supported by BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. RL receives funding support from NCATS (5UL1TR001442), NIDDK (U01DK061734, U01DK130190, R01DK106419, R01DK121378, R01DK124318, P30DK120515), NHLBI (P01HL147835), and John C Martin Foundation (RP124). PS receives funding from the DFG grants STR1095/6-1 and SFB 1382 (ID 403224013).

Author contributionsBJ and JB conceived of the study, conducted analysis, and wrote the manuscript. RL and PS refined the study methodology, reviewed the results, and supported framing of the study’s key message. All authors reviewed the full draft of the article and subsequent revisions and approved the final version for submission.

BJ and JB are employees of BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. PS has received grants and honoraria from Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, CSL Behring, Grifols, consulting fees or honoraria from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc., Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, GSK, Intellia Pharmaceuticals, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk and Ono Pharmaceuticals, participating in leadership or fiduciary roles in Alpha1-Deutschland, Alpha1 Global, and material transfer support for Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Dicerna Pharmaceuticals. RL serves as a consultant to Aardvark Therapeutics, Altimmune, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Cascade Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Glympse Bio, Inipharma, Intercept, Inventiva, Ionis, Janssen, Lipidio, Madrigal, Neurobo, Novo Nordisk, Merck, Pfizer, Sagimet, 89bio, Takeda, Terns Pharmaceuticals, and Viking Therapeutics; has stock options in Sagimet Biosciences; has received institutional research grants from Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galectin Therapeutics, Gilead, Intercept, Hanmi, Intercept, Inventiva, Ionis, Janssen, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sonic Incytes, and Terns Pharmaceuticals; and is the co-founder of LipoNexus Inc.

We thank participants and scientists involved in making the UKB resource available (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the National Health Service (NHS) as part of their care and support. Ethics approval for the UKB study was obtained from the North West Centre for Research Ethics Committee (11/NW/0382). UKB data used in this study were obtained under approved application 41232. Editorial support was provided by Sanna Abbasi, PhD, of Red Nucleus, and funded by BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.