Outpatients with cirrhosis, ascites and minor acute serum creatinine (sCr) changes could have been missed as having acute kidney injury (AKI). This study aims to assess the incidence, clinical features of all AKI stages amongst patients with cirrhosis and various ascites severities.

Materials and MethodsRetrospective study of patients with cirrhosis and ascites from April 2020 to March 2021. Data collected included demographics, clinical features, medications, AKI development, and 6-month follow-up outcomes. Multivariate analysis for factors predicting AKI development and resolution was done.

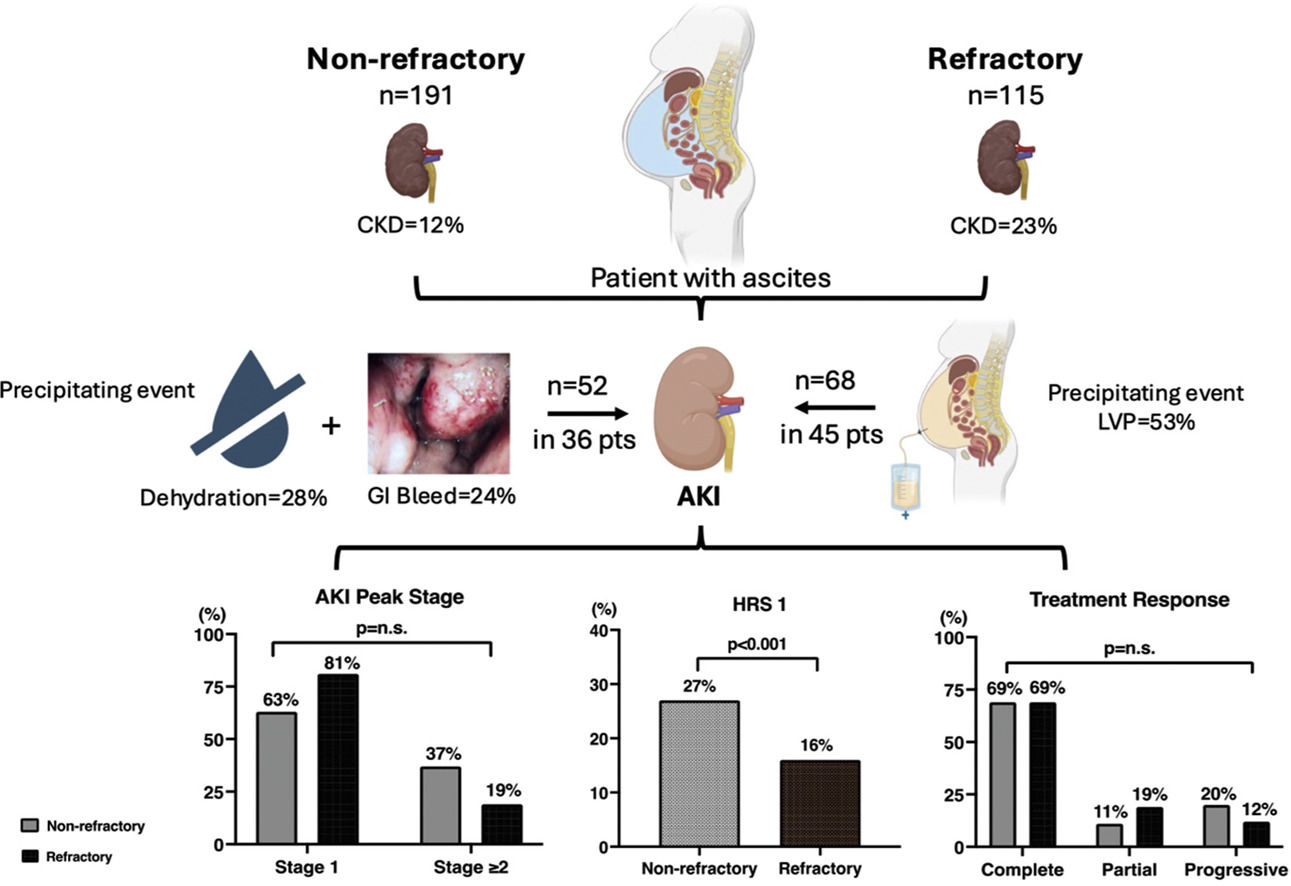

Results115 (38 % of 306) with refractory ascites (RA) were compared to 191 with non-refractory ascites (n-RA), 86 % were outpatients. RA patients had higher baseline MELD-Na (18.1 ± 4.7 vs. 17.2 ± 6.8 in n-RA, p = 0.01) but had similar cirrhosis complications. 98 % RA patients required regular large volume paracenteses (LVP) (p < 0.001 vs. n-RA). AKI occurred in 39 % of RA and 19 % of n-RA patients (p<0.001). Most were stage 1 AKI, treated with albumin ± vasoconstrictor with similar response. 27 % of AKI in n-RA were classified as type 1 HRS (vs.20 % in RA, p < 0.001). Baseline MELD-Na (p = 0.01) predicted AKI development; lower peak sCr predicted AKI resolution (p = 0008). 11 (3.6 %) n-RA and 22 (19 %) RA patients developed acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), with 86 % RA patients having renal failure as part of the ACLF syndrome (p < 0.001 vs. n-RA patients). Both groups had similar 6-month survival.

ConclusionsAKI occurs not infrequently in n-RA patients who are mostly treated as outpatients. Therefore, patients with n-RA need to be monitored closely so to allow prompt diagnosis and treatment of AKI.

Renal failure is the most common complication in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites, occurring in up to 50 % of patients with cirrhosis admitted into hospital [1,2]. The definition of renal dysfunction has undergone significant changes recently [3], and minor degrees of renal dysfunction is now recognized to be associated with negative outcomes [4,5]. The universally accepted diagnostic criteria for acute renal dysfunction, now termed acute kidney injury (AKI), uses a dynamic change in serum creatinine (sCr); and the severity of the AKI is described in stages (Supplementary Table 1) [6]. AKI in cirrhosis can take on many phenotypes [7]. Functional causes of AKI related to hemodynamic changes in cirrhosis are much more common [2], varying in severity between pre-renal azotemia (PRA) to type 1 hepatorenal syndrome (HRS1), with the latter having been renamed as HRS-AKI with slightly modified diagnostic criteria from previous [6]. Treatments for the various forms of AKI differ tremendously [8] and reversal of AKI depends on applying the appropriate treatment option. While clinicians are very familiar with HRS1, the questions that remain are how well clinicians recognize the various forms of AKI, and how well do patients with these newer categories of AKI respond to the treatments designed for the older definitions of renal failure. For example, the CONFIRM study evaluated the use of terlipressin in the treatment of HRS1 [9], but HRS1 is no longer applicable in the description of renal failure in cirrhosis. Furthermore, it is unclear whether patients with earlier stages of ascites have the same susceptibility for the development of AKI, especially the more severe stages of AKI, as these patients are often managed as outpatients and do not have frequent monitoring blood draws. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the incidence, clinical features of all stages of AKI amongst patients with varying severities of ascites at a quaternary academic centre to provide some real-world data on AKI in cirrhosis.

2Patients and MethodsThis was a retrospective study conducted in both inpatients and outpatients with cirrhosis and ascites who attended the Toronto General Hospital from April 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021. Patients with cirrhosis and ascites mentioned at the same visit were identified by Medical Records Department. Manual chart review was done to collect data on demographics, clinical features, medications, ascites severity, AKI development, AKI and patient outcomes at 6 months. The first date of contact within the study period was regarded as the enrolment date and the first laboratory parameters available were regarded as baseline parameters. Patients were excluded if there was no imaging during the study period to confirm the presence of ascites, had incomplete clinical data, or a prior organ transplant. Patients who were on renal replacement therapy (RRT) or already under the care of palliative care unit with no active intervention, or patients with active COVID-19 or human immune-deficiency virus infection were also excluded, so were patients with active liver or non-liver malignancy with an estimated survival of less than 6 months.

Serial sCr values were assessed to determine whether they fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for AKI [6]. Those with a peak sCr of >233 µmol/L (2.5 mg/dL) were further assessed to determine whether they fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of HRS1 [10]. Each AKI episode was evaluated separately for patients with >1 AKI event. Admitted patients were also assessed for the development of other organ failures as per the European Association for the Study of Liver Disease- Chronic Liver Failure (EASL-CLIF) criteria [11] (Supplementary Table 2). AKI outcomes included response to treatment and sCr at end of AKI episode. Patient were followed for 6 months to determine outcomes included AKI recurrence, hospital admissions, liver transplant, and death. Patients were arbitrarily divided into those who had refractory (RA) ascites versus those with non-refractory ascites (n-RA) and compared.

2.1Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were presented as means, standard deviations, medians and ranges, frequencies, and percentages where appropriate. Differences in clinical and demographic parameters, medications, laboratory values, renal function at entry, AKI episodes, ACLF occurrence, and 6-month follow-up data were compared between RA and n-RA patients using Chi-squared tests, Fisher's exact tests, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests as appropriate. Differences in characteristics of individual AKI episodes and hospitalizations between RA versus n-RA patients were analyzed using logistic mixed-effects regression with a random intercept on subject ID. Overall survival for 6-months post-enrolment was compared using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests.

Exploratory multivariable models were used to describe factors independently associated with each of three outcomes: 1) development of any AKI during study period, 2) severity of most-severe AKI episode, among patients with at least one AKI episode, 3) complete versus partial versus no response to treatment in the most-severe AKI episode, among patients with at least one AKI. Multivariable models were fit using logistic regression. All statistical tests were two-sided, using the threshold α<0.05 to determine statistical significance. Analyses were performed in R statistical programming language version 4.3.0.

2.2Ethical statementThe study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Toronto General Hospital. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

3ResultsThere were 527 patients with cirrhosis and ascites identified by the Medical Records Department during the study period, which coincided with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many otherwise eligible patients either did not attend the hospital, or attended virtually and therefore had their blood work performed outside the hospital. Our Ethics Committee did not permit access of government websites for blood work results for research purposes. Despite this, the study eventually enrolled 306 patients. Supplementary figure 1 details the patient flow chart.

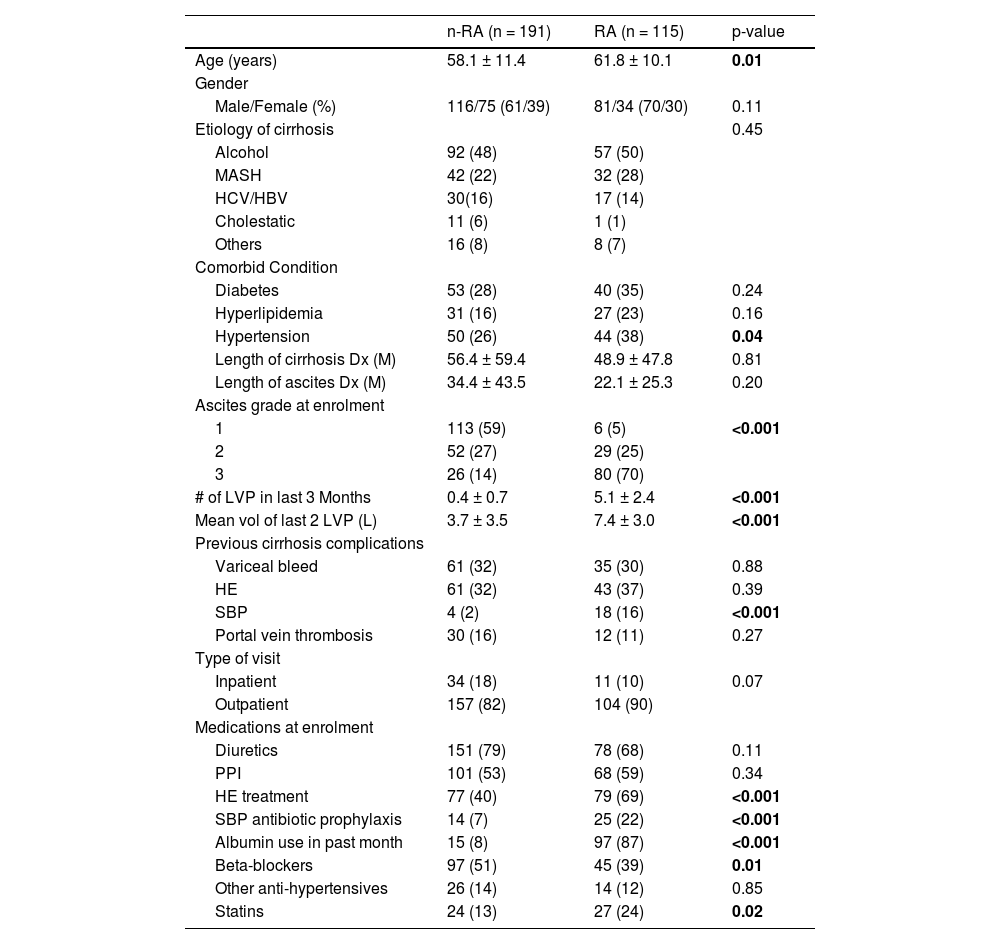

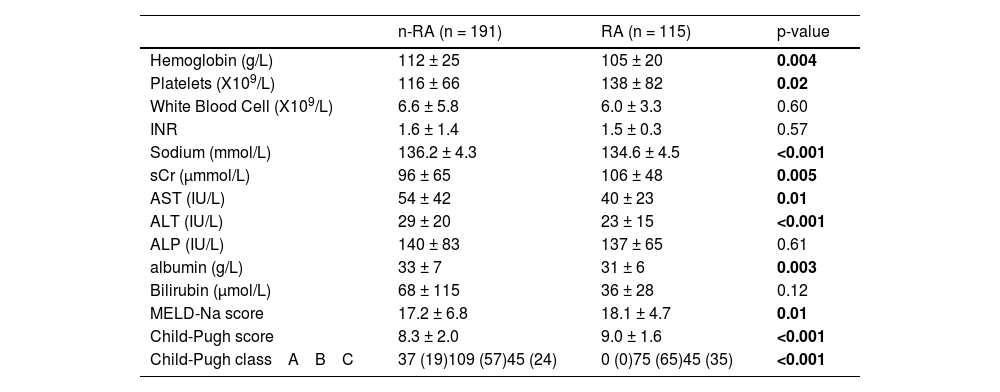

3.1Patient demographicsThere were 197 males and 109 females enrolled with mean age of 59.5 ± 11.1 years, 86 % were outpatients while the remaining 14 % were inpatients. Table 1 shows the patient demographics for both the RA- and n-RA subgroups, while Table 2 shows the enrolment laboratory data. The RA patients were older (62 ± 10 versus 58 ± 11 years, p = 0.01), but there was no difference in cirrhosis etiology, or cirrhosis complications between the 2 groups, with the exception that significantly more RA patients had a history of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) (p < 0.001). 70 % of RA patients had tense ascites (p < 0.001 versus n-RA), with 98 % requiring regular large volume paracenteses (LVP) at 10 to 14-day intervals. Similar proportion of n-RA and RA patients were on diuretics (79 % versus 68 %; p = 0.11), but more RA patients were on medications for encephalopathy, SBP antibiotic prophylaxis (both p < 0.001) and statins (p = 0.02), while more n-RA patients were taking non-selective beta-blockers (p = 0.01). Baseline Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium (MELD-Na) score was higher in the RA group (18.1 ± 4.7 versus 17.2 ± 6.8, p = 0.01). The MELD-Na score in the nRA group was mostly related to a high bilirubin (56 %), more than related to a high INR (22 %) or high sCr (22 %). The higher MELD-Na score of the RA patients is predominantly related to an elevated INR (65 %) and higher sCr (35 %). The significantly more severe liver dysfunction in the RA patients is also reflected in their significantly higher Child-Pugh score of 9.0 ± 1.6 versus 8.3 ± 2.0 in the n-RA patients (p < 0.001).

Patient demographics and clinical features.

Results are expressed as either mean ± standard deviation, or number of cases with the percentages in parenthesis.

Dx: diagnosis; HBV: hepatitis B viral infection; HCV: hepatitis C viral infection; HE: hepatic encephalopathy; L: litres; M: months; MASH: Metabolic-dysfunction associated steatohepatitis; n-RA: non-refractory ascites; PPI: Proton pump inhibitors; RA: refractory ascites; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; sd: standard deviation.

Laboratory parameters at enrolment.

Results are expressed as either mean ± standard deviation, or number of cases with the percentages in parenthesis.

AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; INR: international normalized ratio; MELD-Na: Model for end-staged liver disease-sodium; sCr: serum creatinine.

At enrolment, the mean sCr in the RA group was significantly higher than that in the n-RA groups (Fig. 1a), related to a higher proportion of RA patients having background chronic kidney disease (CKD) defined as a glomerular filtration rate of <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 for more than 3 months [3] compared to the n-RA group (p = 0.02) (Fig. 1b). This is reflected in the consistently significantly higher historical sCr in the RA patients in the previous 3 months (Fig. 1c).

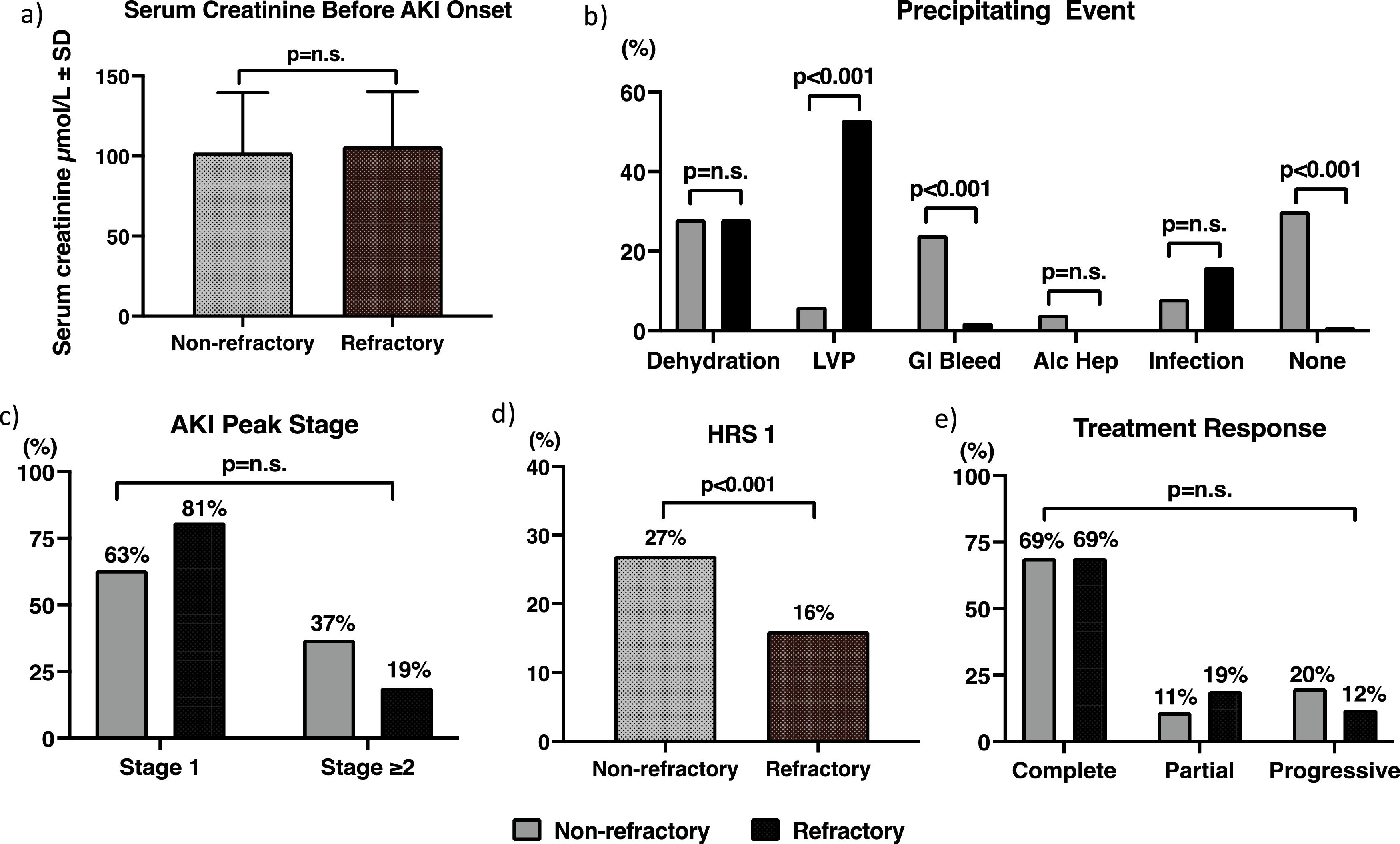

3.3The AKI episodesThe AKI episodes were divided into stage 1 versus ≥ stage 2 as per the International Club of Ascites’ definition [6], as the latter group has been recommended to receive vasoconstrictor treatment [12]. There were 68 episodes of AKI in 45 (39 %) RF patients, versus 52 episodes in 36 patients with n-RA (19 %) (p < 0.001). Both the RA- and n-RA patients with AKI had similar sCr immediately prior to the AKI episodes (Fig. 2a). 70 % of AKI episodes in the n-RA group and 99 % in the RA group had a precipitating event, with gastrointestinal bleeding being significantly more common in the n-RA group, and LVP in the RA group (36 episodes) (Fig. 2b). Other precipitating events amongst the RA patients were dehydration (17 episodes), 10 episodes were related to infection, 3 episodes were related to GI bleed, 2 episodes were related to surgery. Most AKI episodes in both groups were stage 1 at diagnosis. 9 episodes in the n-RA group and 6 episodes in the RA group showed progression of their AKI, so ultimately 19 of 52 (37 %) AKI episodes in n-RA patients and 13 of 68 (19 %) episodes in the RA group were ≥ stage 2 (p = 0.61) (Fig. 2c). Eventually 14 episodes of ≥stage 2 AKI in the n-RA patients and 11 of such episodes in the RA patients fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of HRS1 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2d). None of the patients in the nRA group who developed HRS1 had background CKD, whereas 3 of the patients in the RA group had background CKD related to diabetes. Eight of the 14 episodes of HRS1 already had HRS 1 when patients presented to hospital; 4 of these cases either had an infection or alcoholic hepatitis as the precipitating event for their HRS1; 3 episodes had GI bleed, while 1 episode did not have a precipitating event. For the 6 cases that occurred during follow-up period, 3 were related to GI bleeding, 2 were related to infection and 1 case was related to dehydration. For the RA group, only 4 of the 11 cases were found to have HRS1 at enrolment, 2 following LVP, 1 following an operation for small bowel obstruction and 1 had an episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. For the remaining 7 episodes, 3 were related to LVP, one episode followed a GI bleed, while the remaining 3 episodes were related to infection. The peak sCr reached for all AKI episodes were 226 ± 145 µmol/L and 191 ± 101 µmol/L in the n-RA and RA groups respectively (p = 0.64). There was no correlation between the MELD score at enrolment and the severity of the AKI episode.

The AKI episodes: a) serum creatinine before AKI onset; b) the precipitating events; c) the peak AKI stage reached; d) the incidence of type 1 hepatorenal syndrome; e) treatment response.

AKI: acute kidney injury; alc hep: alcoholic hepatitis; GI: gastrointestinal; HRS1: type 1 hepatorenal syndrome; LVP: large volume paracentesis.

Thirty-six (71 %) of the 52 episodes in the n-RA group and 56 (82 %) of the 68 episodes in the RA group received treatment for their AKI with albumin alone or in combination with midodrine. The total dose of albumin used was 143 ± 190 g over the course of 3 ± 5 days in the n-RA group, and 143 ± 184 g over the same time course (p = 0.93) in the RA group. Fig. 2e shows the treatment response in both groups. 69 % of the 52 AKI episodes in the n-RA group took a median of 3 days (range 1-174 days) to achieve a complete response, reaching a final sCr of 103 ± 26 µmol/L; while 69 % of 68 episodes in the RA patients took a median of 9.5 days (range 1-107 days) (p = 0.99) for a complete response with a final sCr of 108 ± 33 µmol/L (p = 0.94 versus n-RA). Amongst the n-RA patients, 6 (11 %) episodes of AKI showed a partial response and 10 (20 %) episodes progressed. The corresponding numbers in the RA group were 13 (19 %) and 8 (12 %) respectively (p = 0.97 versus n-RA). Nine episodes in the n-RA group and 2 episodes in the RA group required dialysis (p = 0.16) as they were non-responders to vasoconstrictors and albumin and therefore were placed on the liver transplant waiting list. The duration of dialysis was from 7 to 81 days.

3.4HospitalizationsForty-two of the 115 (37 %) RA patients had a total of 69 hospital admissions during the study period, while the n-RA group had 83 admissions in 62 of the 189 (33 %) patients, (p = 0.59 versus the RA group). Most of the admissions occurred in the follow-up period. Amongst the RA patients, infections were the most common cause for admission (48 % of all admissions), with the most common sites of infection outside the peritoneal cavity. The n-RA group, in contrast, had most of their admissions related to liver decompensation (43 % of all admissions) such as variceal bleeding or hepatic encephalopathy. When infection was the cause of hospital admission in the n-RA patients, the most common infection was SBP (41 %) followed by pneumonia (23 %).

Twenty-two of the 69 (32 %) hospital admissions in the RA group and 30 of the of 83 (36 %) admissions in the n-RA group were complicated by the development of ACLF as per EASL-CLIF criteria. The most common organ failure in the RA patients was renal failure (sCr ≥ 2 mg/dL) which occurred in 19 of the 22 ACLF cases. In contrast, liver failure (p = 0.006 versus RF) and coagulation failure (p = 0.01 versus RF) were the 2 most common organ failures observed in the n-RF patients.

3.5Follow-up periodThere were 34 recurrent AKI episodes in 11 RA patients, this compared significantly to 26 recurrent AKI events in 10 n-RA patients (p < 0.001). The mean sCr was 128 ± 114 µmol/L at 3 months and 129 ± 114 µmol/L at 6 months for the RA group, which were significantly higher than the corresponding values for the n-RA group (87 ± 32 µmol/L at 3 months, p = 0.03 versus RA; 86 ± 34 µmol/L at 6 months, p < 0.001 versus RA). As a result, 36 (31 %) of the RA patients were listed for liver transplant compared to 35 patients (18 %) in the n-RA group.

Fifteen patients in the RF group died during follow-up compared to 22 patients in the n-RF group. Fig. 3 shows the survival which was no different between the 2 groups.

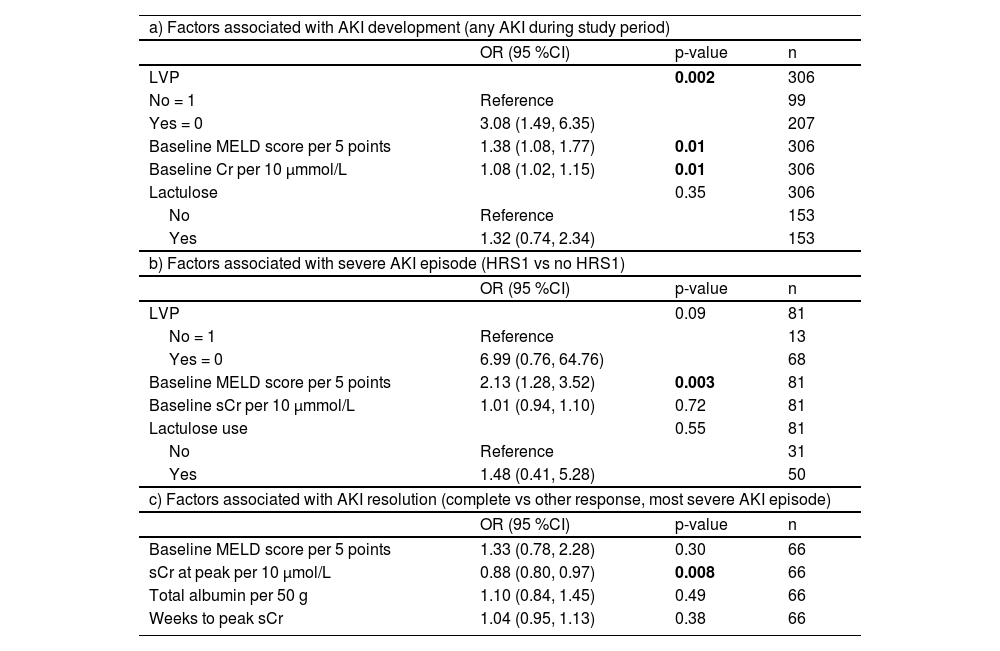

3.6Predictors of AKI development and outcomesMulti-variate analysis shows that the most significant factor associated with any stage of AKI development was LVP, followed by a high baseline MELD or a high baseline sCr. A high baseline MELD was also predictive of a more severe stage when AKI developed, while a lower sCr at peak of the AKI episode was predictive of a complete response to AKI treatment (Table 3).

Multivariate models for the prediction of AKI development and outcomes.

AKI: acute kidney injury; LVP: large volume paracentesis; MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; OR: odds ratio; sCr: serum creatinine.

This study shows that the incidence of AKI was 19 % in n-RA and 39 % in RA patients. These incidence rates are lower than what has been reported for the inpatient with ascites [1,2], but still substantial, especially in the RA population, likely related to the fact that 23 % of the RA patients had CKD. RA patients generally have a gradual reduction in renal function as the severity of the ascites progresses, the so-called type 2 HRS in the old nomenclature [13]. The increasing incidence of metabolic dysfunction associated steatohepatitis and its associated co-morbidities such as diabetes, leading to diabetic nephropathy may also contribute. Patients with CKD are known to have a higher risk for AKI [14], also confirmed in this study. In fact, for every 10 µmol/L increase in the baseline sCr, there is an 8 % increased risk for the development of AKI. It has been proposed that metabolic alterations in the kidneys of CKD such as increased oxidant stress, high oxygen consumption, and low functional nitric oxide activities could increase the susceptibility of these kidneys to further injury [15]. Amongst hospitalized patients with cirrhosis, it has been reported that AKI occurred in an alarmingly high 68 % of patients with CKD [16], likely the results of many interventions that these inpatients received that could further perturb the renal hemodynamics and function.

Although the presence of background renal dysfunction is a predisposing factor for AKI development, additional triggers are often needed for AKI to occur. This was especially true for patients with RA. Disturbance in fluid distribution is an important precipitating factor for AKI development. While patients with n-RA rarely required LVP, dehydration from over-zealous diuretic use or excess lactulose doses causing diarrhoea accounted for over a quarter of cases of AKI for both the RA and n-RA patients. Among RA patients, more than 50 % of the AKI episodes followed LVP. The corollary from this observation is that careful fluid management in patients with tense ascites is of paramount importance. Patients with large ascites have many symptoms including shortness of breath, abdominal pain from abdominal distension and various hernias. This often leads physicians to meet patient requests for a flatter abdomen by prescribing large doses of diuretics for n-RA patients and removing very large volumes of ascites at one time in RA patients. Our findings concur with a recent prospective study which demonstrated that excess volume of paracentesis removed was associated with an increased incidence of AKI, especially if more than 8 litres of ascites is drained despite the use of the recommended dose of albumin [17]. This is likely related to large volume shifts causing further reduction in the effective arterial blood volume, and further activation the vasoconstrictor systems, predisposing these patients to the development of AKI. Perhaps daily low volume paracentesis would have been useful in avoiding the development of AKI [18]. The higher incidence of post paracentesis circulatory dysfunction with increasing volume drained likely explains the development of renal failure [19]. Furthermore, patients who are regularly receiving LVP also have their blood work monitored after each LVP session, which may account for LVP as the most frequent precipitant for AKI in the RA group. The clinical pearl from this observation is that excessively LVP should not be the only approach to the management of RA; rather, judicious sodium restriction should also be implemented to reduce the rate of ascites accumulation [20]. Infection did not appear to be a significant precipitating event for AKI, as patients with infections usually have symptoms that lead them to medical attention early.

Most AKI episodes in both groups were stage 1, but many episodes progressed. Progression was more pronounced in n-RA patients, so that ultimately significantly more n-RA patients developed HRS1. This is not a commonly recognized evolution of AKI in n-RA patients, as one would expect the RA patients with higher prevalence of CKD and higher sCr at enrolment to be more susceptible to HRS1. This possibly is related to the fact that most patients with n-RA are usually managed as outpatients and therefore regular blood draws are less frequent. The RA patients, in contrast, receive regular LVP several times per month, with blood works after LVP as part of their routine care; therefore, minor changes in sCr can be caught and managed before it progresses to more severe stage of AKI. In our particular cohort, some of the nRA patients presented with their AKI as a complication of alcoholic hepatitis, or infection including sepsis. The intense inflammation associated with alcoholic hepatitis or severe sepsis may also contribute to their AKI development. Despite not having terlipressin available, more than two-thirds of patients responded with complete recovery of their AKI with the use of albumin with or without midodrine. This is likely related to the fact that most AKI episodes were stage 1 that were cases of PRA, and the mean peak sCr reached was less than 233 µmol/L or 2.5 mg/dL, as a high peak sCr has been shown to be associated with a reduced response to albumin and vasoconstrictor therapy including terlipressin [21]. Our study also showed that for every 10µmol/L increase in sCr before the start of treatment, there is a 12 % reduction in the likelihood of achieving a complete response. Therefore, it is imperative that patients with ascites, irrespective of its severity, is monitored frequently for the development of AKI and treatment started promptly to achieve AKI reversal.

AKI was a recurrent event in a small number of patients in both the n-RA and RA groups, more common amongst the RA patients. This may be related to the fact that more RA patients showed a partial response to treatment, and therefore setting a higher baseline sCr for the next AKI episode when the next trigger occurs. Indeed, we have observed a significantly higher mean sCr for the RA group at both 3- and 6- months during follow-up. It is envisaged that when terlipressin eventually becomes available in Canada, we will be able to reduce the risk for AKI recurrence, as terlipressin has been shown to be much more efficacious than midodrine in the management of HRS [22].

Other decompensating events led to multiple hospital admissions in 34 % of the entire cohort, without any significant differences between the RA and n-RA patients. Ascites is a strong predictor for hospitalization [23], and in an Italian population, it conferred a 71 % increased risk for hospitalization. This risk increases further when non-liver co-morbid conditions such as diabetes, or cardiovascular conditions are present. The most common indication for admissions in the RA group was related to infections. Cirrhosis associated immune dysfunction and changes in gut microbiota can make the decompensated cirrhotic patient more susceptible to infections, and this susceptibility increased with more advanced cirrhosis [24]. The infections that these RA patients succumbed to were not SBP, as patients with a history of SBP were on secondary prophylaxis. ACLF was noted during some of these admissions. The most common organ failure amongst the RA patients was renal failure, reflecting their advanced hemodynamic abnormalities. In contrast, the n-RA patients had mostly liver related complications as their indications for hospital admission, with liver and coagulation failures as the most common organ failures when ACLF occurred. Despite their repeat AKI episodes and recurrent admissions for decompensating events, their survival over 6 months was similar to what has been reported in the literature [25].

Our study has limitations. Firstly, we could have under-estimated the frequency and severity of AKI episodes because this study occurred at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The inability to access government websites to retrieve patient medical records in other hospital database suggests that we may have also omitted some hospital admissions. The retrospective nature of our study also means that we may have missed some data. However, our database shows that a substantial number of patients continued to come for their ascites care. Finally, we have not provided a validation cohort, whether internal or external. Despite that, our data show what real-world experience with AKI in patients with ascites.

5ConclusionsWe can conclude that patients with n-RA are equally at risk for the development of AKI with a higher likelihood for progression to HRS1 as their RF counterparts. This is partly related to the fact that they attend for medical care less frequently, and some of these patients present with severe liver dysfunction and intense inflammation related to alcoholic hepatitis or severe infection, contributing to AKI and its progression. Therefore, more frequent monitoring of n-RA patients who are mostly outpatients will allow early detection of AKI with the potential for early diagnosis with improved outcomes.

FundingThis study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant provided by Mallinckrodt Pharmaceutical Inc.

Author contributionsData curation: NT, CB; Funding acquisition: FW; Investigation: NT, CB, NS, CT, FW; Project administration: FW; Supervision: NS, CT, FW; Writing-original draft: FW; Writing- review & editing: NT, CB, NS, CT, FW.

FW receives consultant fees from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceutical Inc, and Toronto General Hospital receives grant support from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceutical Inc. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Audrey Kapeleris for initial data screening, and Katrina Hueniken from the Department of Statistics, at Princess Margaret Hospital of University Health Network for performing the statistical analysis.