Up-to-date knowledge of hepatitis C virus (HCV) management among healthcare providers is crucial for improving patient outcomes. This study evaluates physicians' awareness, attitudes, self-efficacy, perceptions, and barriers related to current HCV management guidelines and post-treatment follow-up.

Materials and MethodsWe invited healthcare providers treating HCV patients to complete a 48-question survey regarding their practices, guideline familiarity, and related attitudes.

ResultsThe survey was completed by 183 physicians from 8 countries, including hepatologists (32 %), gastroenterologists (39 %), internal medicine specialists (12 %), and infectious disease specialists (16 %). The majority (95 %) were aware of at least one treatment guideline, with the EASL guideline cited by 84 % and the AASLD guideline by 72 %. Most (94 %) believed post-HCV treatment follow-up was effective for detecting complications, and 93 % recommended continued follow-up. Although 90 % felt well-informed about guidelines, 39 % reported encountering inconsistencies. Sixty-one percent recognized that HCV elimination reduces the rate of decompensation but does not abolish the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Overall, 86 % acknowledged the need for follow-up in patients who achieved sustained virological response (SVR), with the most commonly recommended intervals being six months for non-cirrhotic patients and three months for cirrhotic patients. Minimal barriers to follow-up were reported, with only 1.6 % to 4.4 % not discussing its benefits due to time or resource constraints.

ConclusionsThe surveyed physicians demonstrated a strong awareness of the current HCV guidelines but indicated potential gaps in knowledge and inconsistencies. Continuous education and support are essential to enhance adherence to HCV management protocols.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection continues to be a global health crisis. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, in 2019, there were approximately 58 million individuals living with chronic HCV infection, and 400,000 deaths occurred annually [1]. Over the years, chronic HCV infection has been a leading cause of cirrhosis, HCC, and end-stage liver failure requiring liver transplantation [2]. Interferon (IFN)-based therapy was the sole treatment for HCV infection until 2011, but it had unsatisfactory outcomes and unfavorable side effects profile for many years.

Hepatitis C treatment has evolved rapidly, and several new direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have been approved since WHO issued its first hepatitis C guidelines in 2014 [3]. These drugs have demonstrated high efficacy and safety profiles, enabling viral eradication even in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. As a result, a growing number of patients have achieved sustained virological response (SVR). Currently, a fixed dose of DAAs is accepted as the standard of care for HCV treatment for 8–12 weeks [4]. The SVR in non-cirrhotic patients exceeds 95 % for all genotypes and 80–90 % in cirrhotic patients [5]. For these reasons, eligibility criteria have become more liberal. Therefore, the WHO implemented a strategy in 2016 aimed at eradicating HCV infection as a public health threat by 2030. This strategy has been defined as achieving a 90 % reduction in number of new chronic infections and 65 % reduction in mortality rates compared to 2015 levels [1,3]. Additionally, some countries have or are expanding their HCV treatment programs to treat all patients with HCV infection and ‘eliminate’ HCV in their populations.

Previous studies have shown that patients who achieve SVR tend to experience improvements in liver inflammation, fibrosis, and extrahepatic manifestations independent of the stage of the underlying liver disease [6,7]. However, in patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, long-term data show that HCV eradication does not eliminate the risk of HCC, warranting continued surveillance, especially when cofactors such as alcohol use, obesity, or type 2 diabetes are present [7–9]. Therefore, patients with advanced fibrosis (METAVIR score F3) and cirrhosis (F4) who achieve SVR should remain under surveillance for HCC every six months using liver ultrasound, and alpha-fetoprotein measurement. Additionally, surveillance for esophageal varices using endoscopy should be undertaken as recommended every 1–2 years [3,4,10]. To maximize the benefit of therapy, the risks of reinfection should be emphasized to patients at risk as well as positively reinforcing behavioral modifications. [11,12].

Many hepatitis treatment guidelines are available, such as: the WHO guidelines for the screening, care, and treatment of patients with chronic HCV infection [1], the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) HCV guidelines [10], the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommendations on treatment of Hepatitis C [4] and the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) that offer region-specific guidance for HCV management [13,14]. In addition, national guidelines address specific demographic populations and offer tailored recommendations that help to optimize treatment decisions for different patient groups. The overall shared goals of these guidelines are to provide evidence-based treatment recommendations for using approved DAA therapy and to provide recommendations for the screening and follow-up care of patients with chronic HCV infection.

Healthcare providers (HCPs) play a crucial role in HCV management, including screening, diagnosis, treatment, and post-treatment follow-up. Therefore, HCPs must be aware and up to date with the recent guidelines related to HCV management using DAA therapy, particularly for specific high-risk groups of patients who are at high risk of developing complications, such as cirrhosis or HCC after DAA discontinuation. Moreover, HCPs should maintain a positive attitude that motivates them to engage with patients, promoting better adherence to medication, ensuring regular follow-up appointments, and raising patients' awareness about the screening program, time, and frequency essential to control disease stage progression and detect early complications. This is particularly important in countries like Egypt, which has implemented large-scale mass treatment program and treated more than a million patients [15]. The lack of a well-established post-treatment follow-up program for patients completing HCV treatment highlights the role of clear instructions that could be given to patients through the treating physician during treatment duration.

In this context, we internationally surveyed a group of physicians involved in HCV management, aiming to assess their awareness, familiarity with the international guidelines, attitudes, self-efficacy, perceptions, and barriers related to HCV management and post-treatment follow-up practice.

2Materials and Methods2.1Study sampleWhile no formal sample size calculation was conducted, a minimum of 180 responses was considered adequate for detecting moderate differences (Cohen’s h = 0.4) between groups at 80 % power with α=0.05. Physicians directly involved in HCV management, defined as those prescribing antiviral therapy or managing post-treatment follow-up, were eligible to complete a specifically designed 48-question survey. Survey domains were related to the physicians’ HCV practice, familiarity with guidelines, attitudes, perception, self-efficacy, and barriers they have in their practice. The survey was administered in English. Countries were included based on existing collaborations within the Global NASH Council and the presence of investigators able to coordinate national dissemination. Between June 2022 and April 2023, each national investigator disseminated the survey link to relevant specialists in their respective countries through professional networks, institutional mailing lists, and national gastroenterology or hepatology societies. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and open to all eligible providers.

2.2The HCV provider surveyThe survey was developed by the study team based on previously validated frameworks [16], and subsequently reviewed by an international panel of HCV experts to ensure content validity and contextual relevance. Minor modifications were made following pilot testing with five practicing HCV specialists. Survey authors did not participate as respondents. Their role was limited to study design, survey dissemination oversight, and manuscript preparation.

For this study, physicians’ awareness of HCV treatment guidelines was assessed through a list of questions about their familiarity with and accessibility to the guidelines. In addition, attitudes regarding the importance of post-HCV treatment follow-up were assessed through agreement with a series of statements related to outcome expectancy, perception of the guidelines (strength of evidence and conflicting guidelines), and self-efficacy (comfort while caring for HCV patients and ability to reduce post-treatment risks). Physician perceived external barriers to guidelines adherence were evaluated in the form of agreement with statements addressing time and resource barriers. The level of agreement with each statement was assessed using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Basic physician and practice characteristics such as specialty, career level, practice setting, and the number of HCV patients seen in each period of time, were also collected through the survey.

The survey was self-administered through an online survey platform and completed by participating HCPs using their own electronic devices. The online survey required a click to confirm participation that was displayed before any survey questions appeared so that respondents could read the informed consent form first and then click “Yes” to agree and begin the survey; an option to click “No” and close the page was also provided. The informed consent stated that the respondents could refrain from answering any question that they preferred not to answer either by selecting the “Decline to answer” option or by skipping the question. Respondents were grouped into ‘hepatologists and gastroenterologists’ and ‘other specialties’ for comparison. ‘Other specialties’ includes infectious disease and internal medicine physicians who were actively involved in HCV care. Working days per week were collected to explore if clinical time investment influenced adherence to guidelines.

2.3Statistical analysisOnly subjects completing the survey and pressing the "Submit" button were included in the study sample. However, the electronic data collection system did not require answering all the questions to submit the survey; in case of missing data, only observed data were used for analysis. The distributions of answers are summarized as number and frequencies ( %) for categorical variables and as mean ± SD for continuous variables. Comparison between groups were performed using chi-square for categorical parameters and Kruskal-Wallis for continuous parameters. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

2.4Ethical statementThis study was granted ethical approval by the Inova Health Care System Institutional Review Board, Falls Church, VA, USA. All participants consented prior to the beginning of the survey administration through the “click to consent” process. However, this survey was strictly anonymous. No personal identifiers were collected. This was a one-time questionnaire, and subjects were not re-contacted. All the answers were centrally stored in a secure electronic database and analyzed in the aggregate. The full survey instrument is provided as Supplementary File 1. Furthermore, all research was conducted in accordance with both the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul.

3Results3.1Participant characteristicsA total of 183 HCPs from 8 countries completed the survey: 44 % from Turkey, 28 % from Egypt, 21 % from Taiwan, 6 % from the USA, and <1 % from Cuba, Greece, Malaysia, and the UK. Because recruitment was via institutional and society mailing lists, the denominator of invited participants is unknown, and a response rate could not be calculated. About one-third (32 %) of the participants were hepatologists, 39 % were gastroenterologists, 12 % were internal medicine, and 16 % were infectious disease specialists. Overall, 60 % of respondents were hospital-based, with mean 18 ± 11 years of practice, managing a median (IQR) of 50 (20–250) HCV patients per year (Table 1).

Description of the sample of healthcare providers who completed the survey.

HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; IQR, inter-quantile range; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant; SD, standard deviation; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America.

The distribution of provider and practice characteristics was comparable between specialists (hepatologists and gastroenterologists) and other medical specialties, with no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

3.2Awareness and sources of knowledgeWhen asked to mention all the HCV treatment guidelines they knew (95 % knew at least one), AASLD, EASL, APASL, and WHO guidelines were mentioned by 73 %, 85 %, 12 %, and 29 %, respectively. Non-specialists mentioned national guidelines in addition to international ones more frequently than specialists (gastroenterologists and hepatologists): 42 % vs. 26 % (p = 0.04) (Table 2). The most common source of knowledge about the guidelines was the Internet (48 %), followed by conferences (23 %). The term 'Internet' includes official society websites (e.g., AASLD, EASL), open-access platforms, and online CME tools, but may also have also encompassed unvetted sources suggesting that greater scrutiny is needed to evaluate how source credibility impacts practice. The distribution of answers was similar across medical specialties, although specialists more commonly used medical journals compared to non-specialists (15 % vs. 4 %, p = 0.04) (Table 2). The most followed guideline was EASL (46 %), followed by AASLD (23 %), with no significant differences across specialties (all p > 0.05) (Table 2). Of all survey completers, 50 % reported regularly attending workshops, conferences, or training courses about HCV treatment, most commonly those organized by AASLD, EASL, and the United Conference of Hepato-Gastroenterology and Infectious Diseases (UCHID) (10–12 % each). The distribution of answers was again similar across medical specialties (all p > 0.05) (Table 2). At least 70 % of HCPs applied all guidelines during their routine work, while 4–14 % selected only specific sections (pretreatment assessment, treatment, or management of special populations) (Table 2).

Awareness about the HCV treatment guidelines among healthcare providers.

HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; EASL, European Association for the Study of Liver; APASL, Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver; WHO, World Health Organization; NCCVH, National Committee for the Control of Viral Hepatitis; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DDW, Digestive Disease Week; UCHID, United Conference of Hepato-Gastroenterology and Infectious Diseases.

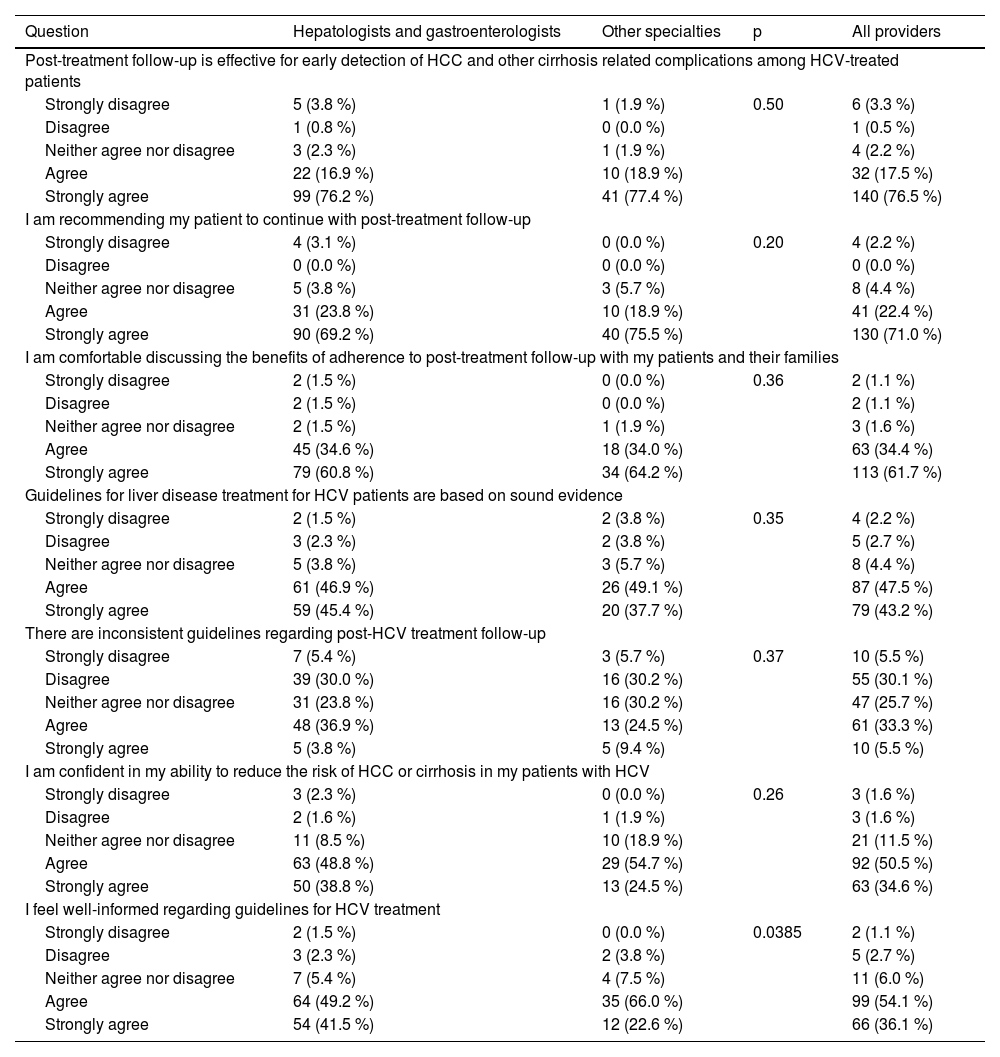

In the context of attitude, perception, and self-efficacy, 94 % of the respondents believed that post-treatment follow-up is effective for early detection of HCC, cirrhosis, and other complications among treated HCV patients, and 93 % recommended that their patients continue with post-treatment follow-up (Table 3). In addition, 91 % of respondents believed that guidelines for HCV treatment were based on sound evidence, but 39 % reported some inconsistencies (Table 3). Finally, 85 % of respondents were confident in their ability to reduce the risk of HCC or cirrhosis in patients with HCV, and 90 % reported feeling well-informed about guidelines for HCV treatment (Table 3). All these answers were similarly distributed between specialist and non-specialist providers (all p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Attitudes, perception, and self-efficacy regarding HCV treatment guidelines among healthcare providers.

HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; HCC, Hepatocellular Carcinoma.

Regarding specific aspects of knowledge, 61 % of respondents were aware that in patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, HCV elimination reduces the rate of decompensation but does not abolish the risk of HCC. The difference between specialists and non-specialists (65 % vs. 51 %) was not statistically significant (p = 0.09) (Table 4). In addition, 81 % believed that surveillance for HCC in patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis should be continued forever (Table 4). Assessment of the liver fibrosis stage using non-invasive tests (NITs) alone prior to treatment was reported by 79 %, and 12 % reported using both NITs and liver biopsy (Table 4). For assessing the fibrosis stage, 85 % of respondents believed that liver biopsy should be reserved for cases where there is uncertainty or suspected additional etiologies of chronic liver disease (Table 4).

Knowledge of management guidelines for fibrosis and cirrhosis in HCV among healthcare providers.

HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; HCC, Hepatocellular Carcinoma.

After treatment, 65 % of HCPs reported asking their non-cirrhotic patients with SVR-12 to repeat ALT and HCV RNA assessments at a later time. Additionally, 96 % of HCPs explained the risk of reinfection to patients from high-risk populations, and 87 % recommended annual HCV RNA testing to patients from those populations (Table 5). Furthermore, 91 % of HCPs advised their SVR patients to get HBV vaccination (Table 5). Overall, 86 % believed that there was a need for following up patients who achieved SVR, with the most commonly recommended follow up periods being 6 months for non-cirrhotic patients and three months for cirrhotic patients. However, hepatologists and gastroenterologists more commonly believed that there was no need to follow-up non-cirrhotic patients compared to other specialists (49 % vs. 28 %, respectively) (Table 5).

Knowledge of post-SVR HCV management guidelines among healthcare providers.

HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; HCV RNA, Hepatitis C Virus Ribonucleic Acid; SVR, Sustained Virologic Response; PWID, People Who Inject Drugs; MSM, Men who have Sex with Men; HBV, Hepatitis B Virus.

During follow-up, the majority of providers (88–96 %) would order liver chemistry tests, alpha fetoprotein, and abdominal ultrasound; 70 % would also do complete blood counts, while only 35 % would double-check HCV RNA levels (Table 5).

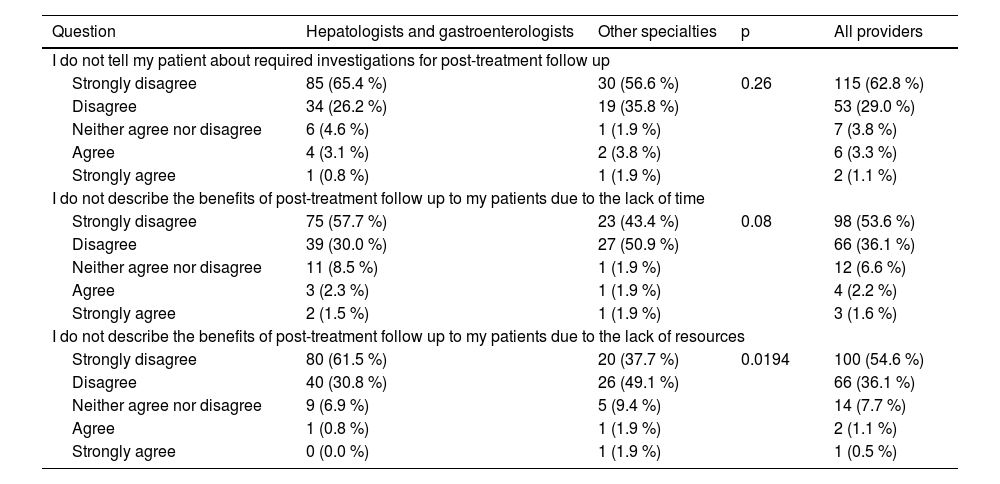

3.6Barriers to implementationRegarding barriers, only 1.6 % to 4.4 % of respondents reported not informing their HCV patients about post-treatment follow-up or its potential benefits due to a lack of time or resources (Table 6).

Barriers reported by healthcare providers.

This international survey aimed to assess the knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy, and barriers of HCPs related to HCV management and post-treatment follow-up guidelines. While much of the data are descriptive, our findings highlight subtle but meaningful discrepancies between guideline awareness and actual implementation, influenced by provider specialty and region. These insights may inform targeted educational interventions and support systems. To contextualize practice variability, it is important to note that Turkey and Egypt have implemented large-scale national HCV programs, whereas Taiwan has a more limited framework. This may contribute to differences in guideline use and perceptions.

In this study, we demonstrated that the included HCPs exhibited a high level of awareness of HCV treatment guidelines. The strong influence of AASLD (73 %) and EASL (85 %) guidelines in HCV underscores their global recognition and trust, likely due to their broad dissemination and solid evidence base. In comparison, APASL and WHO guidelines may be more regionally focused. Furthermore, our results indicate that EASL guidelines are followed by 46 % of respondents, while AASLD guidelines are followed by 23 % of respondents; this variation reflects differences in regional influence and prominence, as most of the included respondents were from countries more familiar with EASL guidelines. For instance, the predominance of EASL use corresponds with the large number of respondents from Turkey and Egypt, where these guidelines are more familiar and accessible.

It is noted that the participants predominantly relied on two sources of knowledge related to HCV guidelines: the Internet (48 %) and conferences (23 %). Specialists were more inclined to utilize medical journals as additional sources of information. These results highlight the important role of online resources as a primary and readily accessible source of up-to-date medical information. Additionally, conferences are another valuable source of updated knowledge, providing both direct interaction with experts and participation in scientific discussions.

We observed that approximately half of the respondents reported regular attendance at workshops, conferences, and training courses organized by international associations. This finding positively reflects that the HCPs are actively seeking regular education and training to stay up to date with advancements in HCV treatment. Interestingly, the distribution of workshop attendance was uniform across different medical specialties. This emphasizes the significance of interdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge sharing in managing HCV effectively.

Buller-Taylor et al. [17] conducted a study to evaluate pre-and post-test information gains about HCV management through a free, one-hour online course for physicians and patients. The study highlighted that the training courses enhanced the ability of physicians to educate and promote patients’ involvement in HCV care. Furthermore, that short online course also enhanced filling knowledge gaps for both physicians and patients in various scenarios through easy and accessible tools. These results are consistent with our findings which emphasized the significant role of disseminating knowledge, mainly through specialized international organizations.

Another key finding in our study was that 70 % of respondents reported applying all sections of the guidelines during their routine work. The majority of respondents (94 %) expressed confidence in the effectiveness of post-treatment follow-up for early detection of complications such as cirrhosis and HCC. In addition, 93 % advised their patients to continue post-treatment follow-up. These findings indicate a strong adherence of included participants to the established guidelines, ensuring comprehensive patient care and effective HCV management.

Furthermore, the results highlighted the respondents' high level of awareness of continuous monitoring to avoid long-term complications in HCV patients. This might be attributed to the high percentage of hepatologists and gastroenterologists who participated in this study, as these specialists are more experienced and continuously updated about guidelines. This is consistent with the findings of Doshi et al. [18], which demonstrated that HCV screening and treatment knowledge was higher among specialty physicians than among non-specialists. This high level of awareness includes detailed topics such as pretreatment methods of fibrosis stage assessment, risk of HCC development, surveillance for HCC in advanced fibrosis or cirrhotic patients, and post-treatment follow-up.

Our analysis showed that most participants trust evidence-based guidelines, as 91 % of respondents declared. However, 39 % of respondents acknowledged encountering inconsistencies in some HCV management guidelines, despite believing that they were based on solid evidence. The contradiction between high trust and reported inconsistencies may reflect regional variations in practice or divergent recommendations across societies (e.g., follow-up intervals, reinfection screening). Furthermore, high self-efficacy may reflect perceived rather than actual performance.

Furthermore, this survey demonstrated a high level of self-efficacy among participants, with 85 % expressing high confidence in their ability to reduce the risk of HCC or cirrhosis complications in HCV patients. Moreover, 90 % of the respondents felt well-informed about HCV treatment guidelines.

The incidence of HCC in patients with cirrhosis and ongoing HCV infection ranges between 1 % - 7 % annually [19]. Ioannou and his colleagues [20] reported that patients with advanced fibrosis remain at high risk of developing HCC even after SVR achievement. This risk may persist up to 10 years after successful treatment in cirrhotic patients or patients with a high FIB-4 score (≥3.25) before treatment. Thus, it is universally accepted that HCC incidence in patients with cirrhosis prior to treatment and SVR achievement is sufficiently high to justify surveillance following HCV eradication [21]. In this context, EASL guidelines recommend that patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis should be included in HCC screening programs [4]. In this study, strong support for post-treatment follow-up was observed considerably, as it was advocated by 86 % of the respondents. Nevertheless, specialists (hepatologists and gastroenterologists) more commonly believed post-treatment follow-up in non-cirrhotic patients was unnecessary. Observed differences in knowledge and attitudes between specialists and non-specialists may reflect variations in formal training, exposure to liver-specific CME, or institutional expectations. Future studies with larger samples may clarify these relationships.

Moreover, we observed that most respondents (88 %–96 %) reported ordering liver-related blood investigations combined with abdominal ultrasounds during post-treatment follow-up. This may reflect their commitment to follow the guidelines and use the available standardized tools to monitor liver health in HCV patients after treatment. In this context, our findings align with the study by Dormanesh et al. [22], which evaluated how well patients with HCV adhered to their physicians’ recommendations and established guidelines for HCV management and follow-up care. This previous research underscored the critical role of effective communication between patients and healthcare providers regarding follow-up care guidelines, which is essential for monitoring serious complications such as HCC.

The results of this survey also confirmed that a high level of knowledge and adherence from HCPs to different international HCV management guidelines and recommendations are prerequisites for the implementation of HCV screening and elimination. Accordingly, in line with WHO recommendations, several countries have implemented ambitious campaigns aiming at eradicating HCV infection as a public health problem by 2030. These efforts will yield the desired results if they are conducted by well-educated HCPs. Egypt has been a global leader in HCV elimination efforts. A mass screening and treatment program was launched in 2018, aiming to screen >60 million individuals and treat millions infected with HCV [23–25]. Georgia also launched its first national campaign aimed at HCV eradication in 2015. In 2022, 2.6 million people have been screened for HCV antibodies, and 80,000 persons with HCV RNA detected were treated [26,27]. Therefore, we emphasize that the lessons from Egypt and Georgia regarding HCV management can be replicated in other countries. Consequently, continuous education for HCPs on HCV management is crucial for enhancing the quality of care for HCV patients and contributing to the global target of HCV eradication by 2030.

Finally, the current study identified minimal barriers to post-treatment follow-up. A minority of respondents (<5 %) reported that they were not informing their patients about follow-up due to time and/or resource restrictions. This finding highlights a widespread acknowledgment of the importance of follow-up by the respondents, even in the presence of possible practical obstacles such as time and resources.

The strengths of this study include the inclusion of a diverse sample of physicians from various countries, which enhances the generalizability of the findings across different healthcare systems and cultural contexts [28]. Additionally, the incorporation of healthcare providers from various specialties and practice settings, including hospital-based environments, offers a comprehensive perspective on knowledge and practices related to HCV management. Furthermore, this study assessed the adherence of HCPs to different specific aspects of HCV management guidelines, offering valuable insights into the extent to which physicians follow established recommendations. This focus is crucial for identifying gaps and areas that need improvement in clinical practice.

However, the study had some limitations worth noting. While the participant pool was diverse, it may not fully capture the experiences of all healthcare providers managing HCV worldwide, especially low-resource community-based practitioners who might have been out of reach for our study sites. The geographic distribution of respondents—heavily concentrated in three countries—introduces a potential source of bias that may limit the broader generalizability of the study’s findings. Additionally, the study relied on self-reported data from healthcare providers, which could introduce recall bias or occasional overestimations of guideline adherence. Despite these limitations, the insights gained from this study remain valuable and can inform future research and clinical practice in HCV management.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, our study's key findings indicate that the participating HCPs demonstrated a strong level of knowledge regarding HCV management, effectively applying this knowledge while also adhering to established guidelines. The study also highlighted the positive attitudes, self-efficacy, and perceptions of these providers, with few barriers reported in HCV management and post-treatment follow-up. Moreover, the survey results reflect the commitment of participating HCPs to continue educating themselves and monitoring their patients after therapy. There are opportunities for improvement, particularly in addressing perceived inconsistencies in guidelines and establishing uniform procedures across different specialties. Overall, these results provide valuable insights into how knowledgeable and engaged HCPs can positively influence the outcomes for patients with HCV infection.

Author contributionsMohamed El-Kassas – study design, study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Yusuf Yilmaz – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Chun-Jen Liu – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Marlen I. Castellanos Fernández – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Yuichiro Eguchi – critical editing of final manuscript; Khalid Al-Naamani – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Doaa Abdeltawab – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Mohammed A. Medhat – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Wah-Kheong Chan – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Stuart Gordon – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Vasily Isakov – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Ming Lung Yu – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Maria Buti – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; George V. Papatheodoridis – study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of final manuscript; Fatema Nader – project oversight and review of manuscript; Andrei Racila – database administration and review of manuscript; Linda Henry – critical review and editing of final manuscript; Maria Stepanova – statistical analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical review and editing of final manuscript; Zobair M. Younossi – study design, study oversight, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical editing of submitted manuscript.

FundingThe study was supported by the Center for Outcomes Research in Liver Diseases.

None.