This paper deals with channel coordination in a socially responsible distribution system comprising of a manufacturer, multiple distributors and multiple retailers under each distributor. The manufacturer intends to swell stakeholder welfare by exhibiting corporate social responsibility (CSR). Demand at the retailers’ end is linear function of price and is influenced by the manufacturer's suggested retail price. In manufacturer-Stackelberg game setting, a new revenue sharing (RS) contract is used to resolve channel conflict and win–win wholesale price and RS fraction ranges are identified in closed forms. It is found that the manufacturer's and the distributors’ wholesale prices of the RS contract are negative when the manufacturer's CSR practice is above of some thresholds. So, the manufacturer's pure profit may be negative though the distributors’ profits are positive because they receive some consumer surplus from the manufacturer.

Increasing trend of globalization, technological improvement and severe competition among the business entities cause enormous effect on the society as well as the environment because companies are under pressure to accelerate their growth by the means of improved product quality and increased production rate. Consequently, the companies are forced by stakeholders and shareholders to perform socially (Dyllick & Hockerts, 2002). Consequently, corporate social responsibility (CSR) becomes an important issue to control the supply chain. In a recent survey, 74 percent of the top 100 U.S. companies, based on revenue, have published CSR reports in 2008, increment from 37 percent in 2005. Globally, 80 percent of the world's 250 largest companies have issued CSR reports in 2008 that highlights social and environmental issues (KPMG, 2008). On social issue, largest apparel retailer GAP admits to charge of its substandard working conditions in as many as 3000 factories worldwide (Merrick, 2004). Nike is often accused for inhuman labor and business practices in Asian manufacturing factories (Amaeshi, Osuji, & Nnodim, 2008). For environmental issues, in 2009, a group of 186 institutional investors having assets of 13 trillion US dollars have signed a statement. It suggests directions to deal with global warming and greenhouse gases. Recent empirical evidence shows that customers are willing to pay a higher price for products with CSR attributes (Auger, Burke, Devinney, & Louviere, 2003). As a result many leading international brands like WalMart, Nike, Adidas, GAP have been impelled to incorporate CSR in their complex supply chains by a code of conducts (Amaeshi et al., 2008).

A significant amount of research has been done in the area of supply chain coordination. Most of these have been concentrated on the direct collaboration between two individual members. The models dealt with resolving channel conflict in three-echelon supply chain are notably fewer. In practice, it is more difficult to cut out channel conflict in a three-tire supply chain by applying coordination contract than a two-tire supply chain. When the number of echelon increases, self cost minimizing/profit maximizing objectives increase. As a result, dimension of the solution space increases and the channel coordination using contract becomes more complex. The problem further intensifies if there are multiple members in some echelons. Due to multiple members, there are several system and cost parameters in each echelon and one-to-one interactions between the members of different echelons are needed as each member has its own reservation. Therefore, apart from the vertical coordination, horizontal coordination is essential for the best performance of the channel. Also, many constraints remain when it comes to carry out any coordination contract for channel members. The constraints are geographical constraints, administrative problems, performance measurement and incentives at individual forms based on local perspective, dynamically interchanging products and the like (Kanda & Deshmukh, 2008).

The purpose of the paper is to incorporate CSR in a three-level distribution channel that consists of a manufacturer, multiple distributors and multiple retailers under each distributor. Besides pure profit, the manufacturer as the leader of the channel considers stakeholders’ welfare through CSR and influences the downstream channel members to behave socially. In the modeling, instead of considering the manufacturer's CSR activity, the effect of CSR in the form of consumer surplus is incorporated in its profit function. In manufacturer-Stackelberg game approach apart from discussing the effects CSR in decentralized and centralized decision making, a new revenue sharing (RS) mechanism is applied to resolve channel conflict and to find win–win profits of the channel members. In particular, the main objective of the proposed model is to explore the effects of CSR on the channel members coordinated profits. Also, how the parameters of the RS contract are affected by the CSR attribute of the channel is examine.

2Literature reviewCorporate social responsibility is the corporate self-regulation which currently does not has unique definition. Dyllick and Hockerts (2002) defined CSR meeting the needs of a firm's direct and indirect stakeholders (e.g. shareholders, employees, clients, pressure groups, communities, etc.), without compromising its ability to meet the needs of future stakeholders as well. Dahlsrud (2008) analyzed 37 definitions of CSR and developed five dimensions of CSR: environmental, social, economic, stakeholder, and voluntariness. Application of CSR in supply chain has emerged in the last two decades. Considering a socially responsible supply chain, Murphy and Poist (2002) suggested a total responsibility approach by adding social issues to traditional economy. Carter and Jennings (2004) explained the necessity of CSR consideration in supply chain decision making through a case study and survey research. Analyzing a French sample data set, Ageron, Gunasekaran, and Spalanzani (2012) derived several conditions for a successful sustainable supply chain management. Cruz (2008) traced equilibrium condition for an environmentally responsible supply chain network using multi-criteria decision making approach. Cruz and Wakolbinger (2008) extended the model to multi-period setting for measuring long-term effects of CSR. Considering a socially responsible supply chain network, Hsueh and Chang (2008) showed that the social responsibility sharing through monetary transfer led to channel optimization. Cruz (2009) developed a decision support system framework for modeling and analysis of a CSR supply chain network. Ni, Li, and Tang (2010) studied a two-tire CSR supply chain assuming the dominant upstream channel members CSR cost which is shared by the downstream channel member through wholesale price contract. Ni and Kevin (2012) developed a two-echelon supply chain by implementing each channel member's individual CSR cost. They examined the effects of strategic interactions among the channel members under game theoretical setting. Panda (2014) and Panda, Modak, and Pradhan (2016) considered CSR supply chains and have used different contracts to resolve channel conflict. They have used Nash bargaining product to divide surplus profit between the channel members.

Supply chain coordination is essential to improve its performance (Modak, Panda, & Sana, 2015a, 2015b, 2015c; Sarkar, 2013, 2016; Sarkar, Saren, Sinha, & Hur, 2015). Focusing on the multi-echelon supply chain, Munson and Rosenblatt (2001) developed a supplier–manufacturer–retailer supply chain. They explored coordination using quantity discounts on both ends of the supply chain to decrease costs compared to concentrating only on the lower end. Jaber, Osman, and Guiffrida (2006) extended Munson and Rosenblatt's (2001) model by assuming profit function, discount dependent demand and profit sharing. Van Der Rhee, Van Der Veen, Venugopal, and Nalla (2010) introduced a new type of revenue sharing contract mechanism for multi-echelon supply chains between the most downstream entity and all upstream entities. Saha, Panda, Modak, and Basu (2015) examined mail-in-rebate and downward direct discount coordination contracts for a three-echelon supply chain and analyzed superiority of one over the other. Panda, Modak, and Basu (2014) considered a three-echelon supply chain and used disposal cost sharing as the coordination contract. Ganeshan (1999) analyzed a more complex channel structure where multiple suppliers supplied goods to multiple retailers through one distributor. Khouja (2003a) considered a three-echelon supply chain in which, at each stage, there are multiple members and each member could supply to two or more buyers. Ben-Daya and Al-Nassar (2008) assumed that shipment between the two stages could be made before a whole lot was completed. In an another work, Khouja (2003b) proposed an algorithm for optimal synchronization which starts from supply of raw materials and ends at customers. He provided some guidelines for incentive alignment along the supply chain. Cárdenas-Barrón (2007) generalized the model of Khouja (2003b) by considering an n-stage-multi-customer supply chain inventory model, where there is a company that could supply products to several customers. Jaber and Goyal (2008) investigated the synchronization of order quantities in a three-level supply chain consisting of multiple buyers in first level, one manufacturer in second level and multiple retailers in the third level. They showed that when the players in the chain agreed to coordinate, the local costs for the players either are remained the same as before coordination, or decreased. They had not proposed any coordination contract that resolves channel conflict. Zhang (2013) developed a supply chain that consists of multiple players in different echelons. They considered finite production capacity of the suppliers and determined the optimal decisions over a finite time horizon considering reverse logistics. However, the existing literature on supply chain has not addressed the issue of coordination and profit sharing in a conventional distribution channel, where a manufacturer sells its products through multiple distributors and multiple retailers.

The present study differs from the prior works as follows. First, it considers a conventional three echelon distribution channel that is close to realistic structure of a supply chain and analyzes channel members decisions for the socially responsible manufacturer's CSR practice. Second, previous researches have explored CSR, effects of CSR on two-level supply chain and channel coordination discretely. In contrast, the present paper examines the channel coordination issues in a socially responsible distribution channel. Although, Hsueh and Chang (2008) used exogenous monetary transfer to coordinate a socially responsible supply chain network, this paper uses an endogenous procedure not only to coordinate the channel but also to distribute the surplus profit among the channel members. Third, in Ni, Li, and Tang (2010), the supplier performs CSR and the downstream firm shares the CSR cost through wholesale price contract though channel coordination is not examined. Assuming CSR cost of each channel member, Ni and Li (2012) found win–win profits through strategic interaction. The present paper assumes that the manufacturer as the leader of the channel practices CSR and uses RS contract to cut out channel conflict. When a channel member uses RS contract, it interacts with each of its downstream channel members independently. An upstream member always has different reservation for different downstream member because it receives unequal facilities from different downstream channel members.

3NotationThe following notations are used to develop the model.P manufacturer suggested retail price demand of ijth (i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n) retailer in decentralized decision making demand of jth (j=1, 2, …, n) distributor in decentralized decision making demand of manufacturer in decentralized decision making demand of ijth (i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n) retailer in centralized decision making unit selling price of ijth (i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n) retailer in decentralized decision making unit selling price of ijth (i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n) retailer in centralized decision making unit wholesale price of jth (j=1, 2, …, n) distributor in decentralized decision making unit wholesale price of manufacturer in decentralized decision making manufacturer's marginal cost profit of ijth (i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n) retailer in decentralized decision making profit of jth (j=1, 2, …, n) distributor in decentralized decision making pure profit of manufacturer in decentralized decision making total profit of manufacturer in decentralized decision making channel's pure profit in centralized decision making channel's total profit in centralized decision making consumer surplus in decentralized decision making consumer surplus in centralized decision making profit of ijth (i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n) retailer under revenue sharing contract profit of jth (j=1, 2, …, n) distributor under revenue sharing contract pure profit of manufacturer under revenue sharing contract total profit of manufacturer under revenue sharing contract fraction of revenue that ijth (i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n) retailer keeps with itself fraction of revenue that jth (j=1, 2, …, n) distributor keeps with itself corresponding to ijth (i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n) retailer optimal selling price of ijth (i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n) retailer under revenue sharing contract unit wholesale price of jth (j=1, 2, …, n) distributor to ijth (i=1, 2, …, nj; j= 1, 2, …, n) retailer under revenue sharing contract unit wholesale price of manufacturer to jth (j=1, 2, …, n) distributor under revenue sharing contract unit wholesale price of manufacturer to jth (j=1, 2, …, n) distributor under corresponding to ijth (i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n) retailer revenue sharing contract

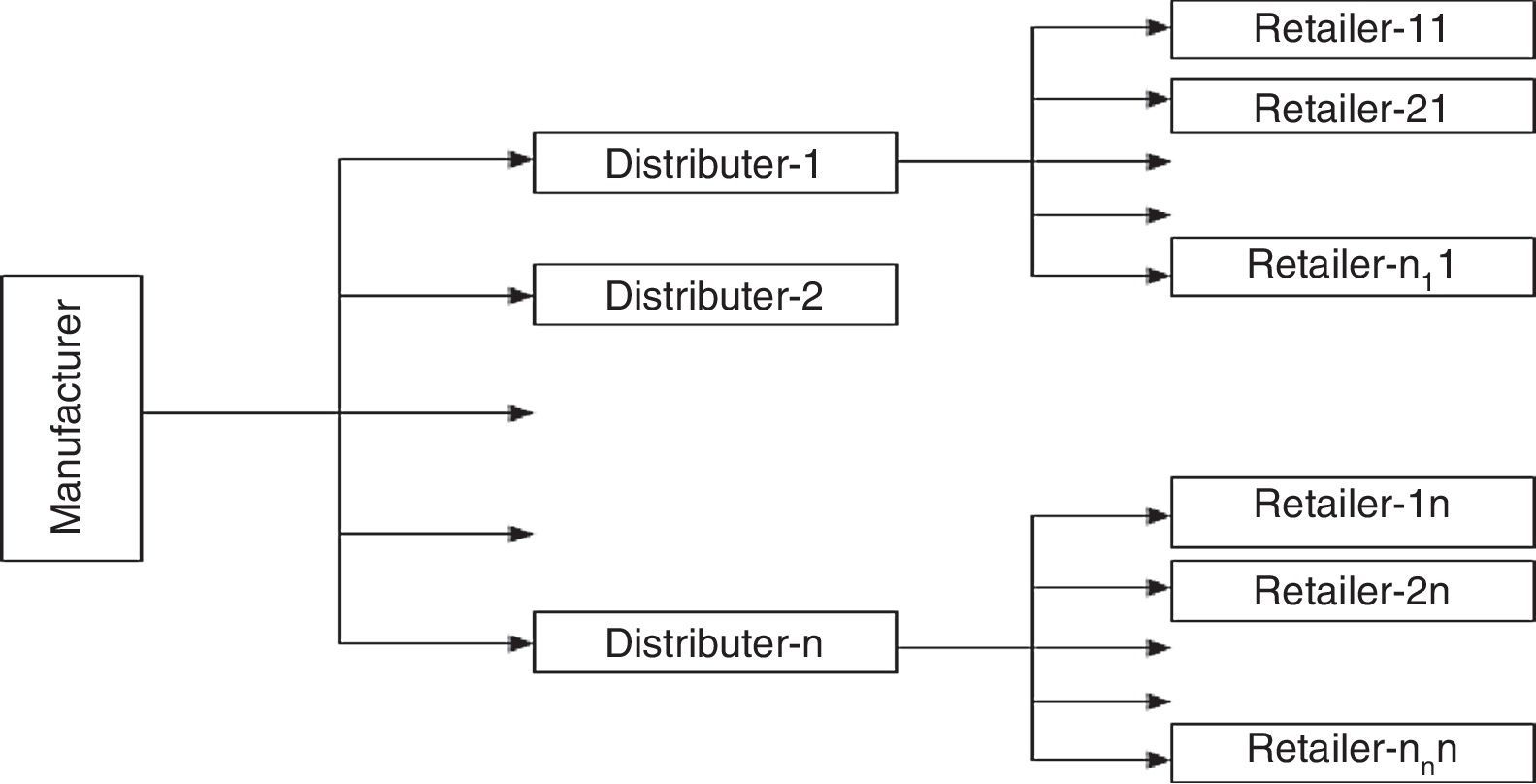

Consider a three-tier conventional distribution channel that consists of a manufacturer, multiple distributors and multiple retailers associated with each distributor. The channel structure is displayed in Fig. 1. The manufacturer produces and supplies a product in a single lots to n distributors. The jth, j=1, 2, …, n, distributor supplies the product to its nij, i=1, 2, …, nj, number of retailers. Finally, the retailers sell the product to the customers. It is customary to assume that shortages are not allowed at any level of the channel and lead time is zero. That is, the product flows from the upstream to the downstream channel members without any delay when demand occurs. Assume that a particular retailer is associated with a particular distributor, i.e., for each retailer there is only one available distributor and it is quite common in current business practice.

The marginal production cost of the manufacturer is c and it sales the product to the distributor at a wholesale price wm. The jth, j=1, 2, …, n, distributor sales the product to its associated nij, i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n, retailers at the wholesale price wjd and the ijth retailer sales the product at the retail price pijr. For analytical simplicity, we assume that the system running cost of each of the channel member is normalized to zero because, in such cases, the qualitative results will not be altered.

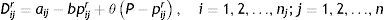

Assume that the ijth retailer can choose the retail price pijr under the condition that the manufacturer suggests a retail price p. Here, the demand is linear in retail price and the customers demand at the ijth retailer's end is given by

The term aij is the market potential for the ijth retailer, b is the customers price sensitivity for the product. Here, θP−pijr represents the customers reference price effect on demand. If p>pijr then the customers enjoy the utility gain and it has positive effect on demand. When p

In the current global environment companies are pressurized to operate their complex supply chain networks socially such that their corresponding stakeholders are benefitted and bad environmental issues are solved to some extent. A commonly noted response to this pressure is the primary firm introduces code of conduct to its business practice to be socially responsible (Pedersen & Andersen, 2006). Here, the manufacturer who is the leader of the channel exhibits CSR to the stakeholders of the channel. For quantitative analysis, we consider the effect of the CSR in the form of consumer surplus in the modeling rather than the CSR activities which manufacturer performs. Interestingly, a firm's CSR is accounted by the consumer surplus that it accrues form the stakeholders (Kopel & Brand, 2012; Lambertini & Tampieri, 2010; Modak, Panda, Sana, & Basu, 2014; Modak, Panda, & Sana, 2015c; Ni & Li, 2012; Panda, Modak, Basu, & Goyal, 2015). Consumer surplus is the difference between maximum price that the consumers are willing to pay for a product and market price that they actually pay for the product. In the present model, the consumer surplus can be found as

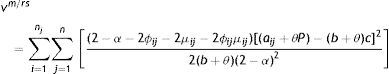

If α∈(0,1) is the fraction of CSR that is socially responsible manufacturers concerned, then the manufacturer accounts α∑i=1nj∑j=1nDijr22(b+θ) as consumer surplus in its profit. Here, α=0 implies that the manufacturer is pure profit maximizer and α=1 represents that the manufacturer is the perfect welfare maximizer. Since the manufacturer is socially responsible, its profit function consists of pure profit that is received through selling the product and consumer surplus through CSR practice. Under this situation, we derive the decentralized and centralized decisions.

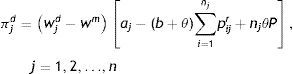

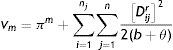

4.2Decentralized decisionsIn decentralized decision making, the channel members operate independently and maximize their individual profit functions. The CSR goal is the manufacturer's own and it is aligned with the channel through a code of conduct. We consider the manufacturer-Stackelberg game, where the distributors are the manufacturer's immediate followers and the retailers follow their respective distributors. It is a sequential move game, where the manufacturer enforces its own strategy on the distributors. Based on it, a distributor finds its own strategy and enforces it on the retailers who are associated with it. Finally, depending on the optimal strategy of the distributor, the associated retailers identify their strategies. In fact, the entire decision making process consists of two Stackelberg games. One is between the manufacturer and the distributors and the other is between the distributors and their corresponding retailers. We use backward induction to find the sub-game perfect solution of the games. The profit function of the manufacturer, the distributors and the retailers are respectively as follows

Total profit of the manufacturer is the sum of pure profit and the consumer surplus that it accrues from the stakeholders and is given by

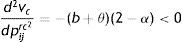

Using backward induction, the optimal solutions can be found and are presented in Table 1. Moreover,

i.e., the profit functions of the channel members are concave. Using optimal wholesale prices of the manufacturer and the distributors and retail prices of the retailers, order quantities of the retailers and the distributors and the profits can be determined and are presented in Table 1. Also, using these values, pure profit and consumer surplus and hence total profit of the manufacturer are determined and are depicted in Table 1.Optimal values in centralized and decentralized decision making.

| Optimal | Decentralized channel | Centralized channel | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | jth Distributer | ijth Retailer | ||

| Price | 4Sb+θ | aj+njθP+4njS2nj(b+θ) | 2njaij+aj+3njθP+4njS4nj(b+θ) | (1−α)(aij+θP)+(b+θ)c(2−α)(b+θ) |

| Order quantity | – | – | 2aij+θP4−aj+4njS4nj | (aij+θP)−(b+θ)c(2−α) |

| Pure profit | (4−α)[(a+θnrP)−(b+θ)nrc]2(8−α)2(b+θ)nr | [aj+njθP+4njS]28nj(b+θ) | [2njaij−aj+njθP−4njS]216nj2(b+θ) | (1−α)∑i=1nj∑j=1nTij2(2−α)2(b+θ) |

| Consumer surplus | ∑i=1nj∑j=1n2aij+θP/4−aj+4njS/4nj22(b+θ) | — | — | ∑i=1nj∑j=1n[Tij/(2−α)]22(b+θ) |

| Total profit | (4−α)(a+θnrP)−(b+θ)nrc2(8−α)2(b+θ))nr+∑i=1nj∑j=1n[2aij+θP/4−aj+4njS/4nj]22(b+θ) | [aj+njθP+4njS]28nj(b+θ) | [2njaij−aj+njθP−4njS]216nj2(b+θ) | ∑i=1nj∑j=1nTij22(2−α)(b+θ) |

Notice from Table 1 that

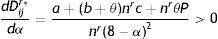

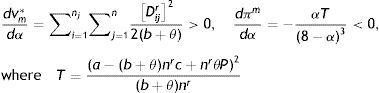

Moreover,To perform more competitively through CSR practice, the manufacturer reduces its wholesale price. In response, the distributors and the retailers reduce their wholesale prices and retail prices, respectively, which encourage the customers to buy more. As a result, the demand in decentralized system increases. Also, observe thatBut,

whereThe CSR objective of the manufacturer influences its pure profit. CSR attribute of the manufacturer is inversely related to its pure profit but directly proportional to its total profit because the consumer surplus that is accrued from the stakeholders over compensation of the loss of pure profit. On the other hand, profits of the distributors and the retailers increase with increasing CSR of the manufacturer because the demand in the channel increases. Although the distributers and the retailers reduce their respective selling prices for the manufacturer's CSR, they earn higher profits with increasing CSR of the manufacturer because the demand of the channel is directly proportional to CSR. From the above discussion, we have the following proposition.Proposition 1 (i) The manufacturer's and the distributors’ wholesale prices as well as retail price of the product decrease with increasing CSR but the demand of the product behaves inversely. (ii) Total profit of the manufacturer, profit of the distributors and the retailers’ increase, but pure profit of the manufacturer decreases with increasing CSR.

In centralized decision, there is a single decision maker who produces a product in a single lot and sales it to the customers. The channel members cooperate and find out decision that maximizes the supply chain performance. The total profit of the channel is the sum of pure profit and the consumer surplus that the channel accrues from the stakeholders, and it is given by

The necessary condition, dvcpijrc=0, for the existence of the optimal solution yields the optimal value of pijrc as follows.

Moreover,

i.e., the optimal selling price provides global maximum for the centralized channel. Using optimal selling price, the other values are found and depicted in Table 1.Observe that

The manufacturer's social responsibility influences the retail price of the centralized channel. When the manufacturer puts more weight on CSR, the channel price decreases. As the order quantity is inversely related to the retail price, the order quantity increases with the manufacturer's increasing CSR. Moreover,i.e., pure profit of the channel decreases but total profit of the channel increases with increasing CSR of the manufacturer, because the consumer surplus accrued from the increase of the stakeholders. Also, the increment of consumer surplus is higher than the decrement of pure profit. The socially responsible centralized channel is more efficient than a pure profit maximizing channel. The channel increases its sales quantity by reducing the retail price. As a result, the channel compensates the loss of pure profit by accruing consumer surplus even this provides some extra profit to the channel. This observation can further be justified from (10) as follows. pijrc*|α=1=c, i.e., when the manufacturer is the pure profit maximizer, the channel retail price is same as the marginal cost of the channel. Then, from Table 1, it follows that the channel's pure profit is zero and the channel accrues only the consumer surplus through CSR practice. Thus we have the following proposition.Proposition 2In centralized channel, (i) retail price of the product decreases with increasing CSR of the manufacturer and (ii) total profit increases though pure profit of the channel decreases with increasing CSR.

Notice that vc*>vm*+∑j=1nπjd*+∑i=1nj∑j=1nπijr*, i.e., double marginalization exists in the channel and transfer pricing policy must be applied to obtain the best channel performance.

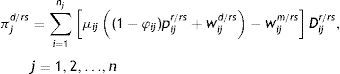

4.4Channel coordination using revenue sharing (RS) contractWhen centralized decisions are implemented for the channel best performance, the manufacturer and the distributors are benefited though the retailers’ profits are less compared to decentralized profits. Thus, the retailers have no reason to accept the centralized decision unless they receive some incentives that ensure at least their decentralized profits. In such case, we assume that the channel members jointly apply RS contract to resolve conflict among them. RS contract is a coordination mechanism offered by the upstream member to the downstream member, which modifies the downstream members’ profit (and also the upstream members’ one) so as to incentive it to make decisions coherent with the supply chain's total optimization. The manufacturer proposes the RS contract wjm/rs,μij, 0<μij<1 (j=1, 2, …, n) to the jth distributor. That is, the manufacturer supplies the product to the jth distributor at a wholesale price wjm/rs, instead receives a fraction of revenue μij from the distributor that it creates. To encourage each of its retailers, the jth distributor supplies the product to ith retailer (i=1, 2, …, nj) at a wholesale price wijd/rs and claims φij, 0<φij<1 percentage of revenue from the retailer that it generates. In response to the upstream channel members cooperative initiatives, the ijth retailer (i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n), sets the retail price pijr/rs. Notice that, in the proposed nested revenue sharing setting, each upstream channel member sets different wholesale price and claims different revenue sharing from different downstream channel members. In a multi-members and multi-level distribution channel, the general practice is that upstream channel member analyzes the situation of its downstream members in one-to-one basis and takes decision. It is very common in marketing channel that an upstream channel member provides more facilities to some of its downstream members than the others because it earns more from those members. Obviously, how much incentive an upstream member can provide to a downstream member that depends on how much it earns from that member. Indeed, this assumption makes the model realistic and it is common in marketing practice. Under RS contract, profits of the ijth retailer, the jth distributor, pure profit and total profit of the manufacturer are respectively as

The ijth retailer will selfishly maximize its profit function, πijr/rs and necessary condition to obtain optimal solution, dπijr/rs/dpijr/rs=0 yields

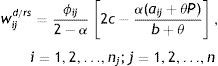

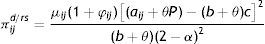

The revenue sharing contract will align the ijth retailer and the jth distributor's decisions only when pijr/rs=pijrc*. Simplifying, the jth distributor's optimal wholesale price for the ijth retailer, we have

Thus, when the jth distributer, j=1, 2, …, n, sales the product to its ijth, i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n, retailer at the wholesale price wijd*, the ijth retailer sets the centralized retail price. Like the retailer, the distributor will also selfishly maximize its wholesale price in the RS contract. From (16), the necessary condition for the maximization of the jth distributor's profit function yields the wholesale price as

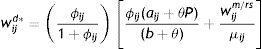

The channel will be coordinated only when wijd/rs=wijd*. Simplifying the expression, the manufacturer's wholesale price for the ijth retailer can be found as

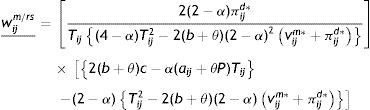

But, in the decision making context, it is not possible as well as feasible for the manufacturer to set different wholesale price for different retailers under a single distributor. Thus, we assume that the manufacturer sets the wholesale price of the jth distributor as the weighted mean of the wholesale prices of its corresponding retailers. As such, the wholesale price of the manufacturer for the jth distributor is

Therefore, as long as 0<ϕij<1, 0<μij<1, i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n, the manufacturer sets wholesale price wjm/rs for the jth distributor. In response, the jth distributor sets the wholesale price wijd/rs for the ijth retailer and the ijth retailer sets the centralized retail price. Furthermore, in pure profit maximizing distribution channel as long as 0<ϕij<1, 0<μij<1, i=1, 2, …, nj; j=1, 2, …, n, lower wholesale prices of the channel members in comparison to the marginal cost of the manufacturer ensures channel coordination. Here, in the socially responsible distribution channel, we have

From (19), notice that wjm/rs is the convex combination of wijm/rs, as each wijm/rs

Using the optimal wholesale prices in (11)–(14), optimal profits of the channel members under RS contract are found as follows

Notice that vm*+∑j=1nπjd*+∑i=1nj∑j=1nπijr*=vc*, i.e., the channel conflict is resolved by using the RS contract and we have the following proposition.Proposition 3 The sets of RS parameters wjm/rs,μij and wijd/rs,ϕij, 0<ϕij<1, 0<μij<1, i=1,2,…,nj;j=1,2,…,n coordinates the socially responsible distribution channel.

Although the proposed RS contract resolves the channel conflict, it is acceptable to the channel members only when they receive win–win outcomes. Cachon and Lariviere (2005) have mentioned that, in a pure profit maximizing supply chain, surplus profit due to channel coordination is arbitrarily distributed among the channel members and it depends on the revenue sharing fraction ϕij and μij, i=1,2,…,ni;j=1,2,…,n. The win–win outcomes of the channel members are ensured if they receive at least equal to their respective decentralized profits. As such, we have the following proposition.Proposition 4 In a distribution channel with CSR manufacturer, the RS contract cuts out channel conflict and leads to win–win outcomes for the channel members for wijd/rs∈wijd/rs_,wijd/rs¯, wjm/rs∈wjm/rs_,wjm/rs¯), ϕij∈(ϕij_,ϕij¯),μj∈(μj_,μj¯), where wijd/rs_,wijd/rs¯, wjm/rs_,wjm/rs¯, ϕij_,ϕij¯, μj_,μj¯ are given in Table 2. Ranges under revenue sharing contract. See appendix and Table 2. Manufacturer jth Distributer ijth Retailer Wholesale Price Min ∑i=1njDijr/rswijm/rs_∑i=1njDijr/rs wijd/rs_ – Max ∑i=1njDijr/rswijm/rs¯∑i=1njDijr/rs wijd/rs¯ RS fraction Min – ∑i=1njDijr/rsμij_∑i=1njDijr/rs φij_ Max – ∑i=1njDijr/rsμij¯∑i=1njDijr/rs ϕij¯ Pure profit Min ∑i=1nj∑j=1n[vijm*−αTij22b+θ2−α2] – – Max ∑i=1nj∑j=1n1−αTij22b+θ2−α2−πijd*+πijr* – – Total profit Min vm* [aj+njθP+4njS]28nj(b+θ) [2njaij−aj+njθP−4njS]216nj2(b+θ) Max ∑i=1nj∑j=1nTij2b+θ2−α−πijd*+πijr* ∑i=1njTij2b+θ2−α−vijm*+πijr* Tij2b+θ2−α−(vijm*+πijd*)

Using the win–win ranges of the RS contract's parameters, the profit ranges of the channel members can be determined and are presented in Table 2.

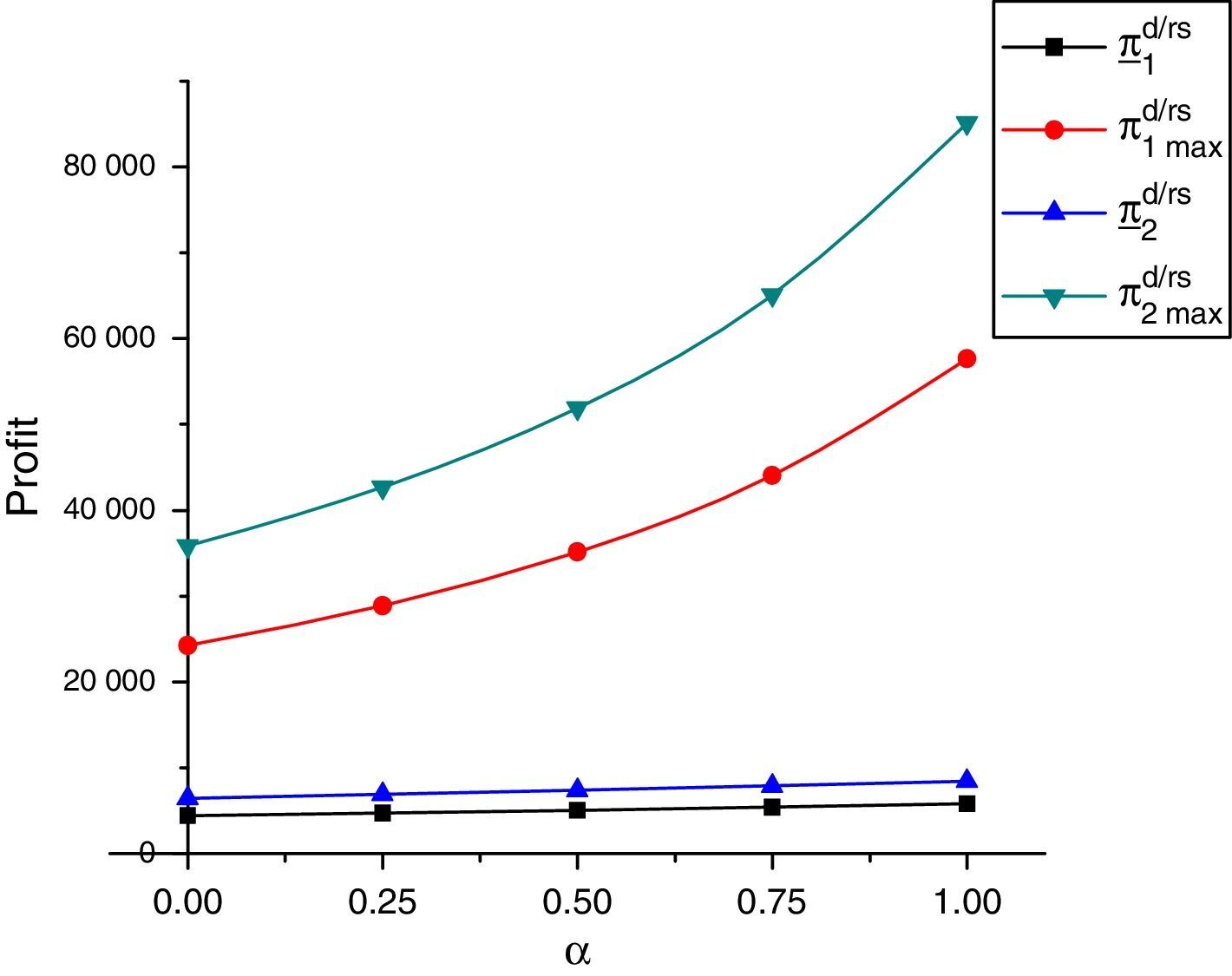

4.5Effects of CSR on the channel coordinated decisionIn a socially responsible distribution channel, the proposed RS contract resolves channel conflict and finds win–win pure profits for the channel members and win–win total profit for the manufacturer. Notice that dwjm/rs_/dα<0 and dwjm/rs¯/dα<0 for any α∈(0,1) and j=1,2,…,n, i.e., win–win wholesale price range of the manufacturer for the jth distributor decreases with its increasing CSR practice. Eventually, wjm/rs¯<0 if α>αjm¯, where αjm¯ is the real root of the equation ∑i=1njDijr/rs−wjm/rs¯=0 and wjm/rs_<0 if α>αjm_, where αjm_ is the real root of the equation ∑i=1njDijr/rs−wjm/rs_=0. Therefore, the wholesale price of the manufacturer for the jth distributor is negative for αjm¯<α<1, Also, from Table 2, it is observed that πm/rs¯<0 if α>α1¯, where α1¯, is the real root of the equation ∑i=1nj∑j=1n(1−α)Tij2−πijd*+πijr*(b+θ)(2−α)2=0 and πm/rs_<0 if α>α1_, where α1_, is the real root of the equation ∑i=1nj∑j=1n2(b+θ)(2−α)2vijm*−αTij2=0. Furthermore, dπm/rs¯/dα<0 and dπm/rs_/dα<0 for any α∈(0,1), i.e., the manufacturer's pure profit range under RS contract decreases with increasing CSR practice. Therefore, the manufacturer's pure profit will be negative for any α>α1. Thus, we have the following proposition.Proposition 5 In a socially responsible distribution channel, under RS contract, the manufacturer's (a) wholesale price for the jth distributor, j=1, 2, …, n (i) decreases with increasing CSR, (ii) is negative for any α>αjm¯, and (b) pure profit (i) decreases with increasing CSR and (ii) is negative for any α1¯<α<1.

The wholesale price of the manufacturer in the RS contract in a socially responsible distribution channel is quite different from that of a pure profit maximizing distribution channel. In a pure profit maximizing distribution channel, the wholesale price of the RS contract is always non-negative. But this result does not hold in a socially responsible distribution channel. Furthermore, when the manufacturer puts more weight on CSR, it also reduces the wholesale price to encourage the retailer to sell more units by decreasing the retail price. The intention of the manufacturer is not to coordinate the channel but rather to encourage the retailer to sell more units through a lower selling price. The manufacturer implements this by selling the product to the retailer below the marginal production cost. So the wholesale price may be negative because it is inversely related to the manufacturers CSR, i.e., a corporately socially responsible manufacturer pays the retailer to sell units additional to the decentralized order quantity. So, CSR is purely a costly endeavor to the manufacturer. Observe from Table 2 that dwijd/rs¯/dα<0 and dwijd/rs_/dα<0 for any α∈(0,1). Moreover, wijd/rs_ and wijd/rs¯ are negative for any α>2c(b+θ)(aij+θP)=α2=αijd, say. In Table 2, dπjd/rs_/dα>0 and dπjd/rs¯/dα>0 for any α∈(0,1). Thus we have the following proposition.Proposition 6 Under RS contract, (a) the wholesale prices of the distributors (i) decrease with increasing α, (ii) are negative for αijd<α<1, i=1,2,…,nj;j=1,2,…,n and (b) profits of the distributors are inversely proportional to the manufacturer's CSR.

We consider a distribution channel consisting of a manufacturer (M), two distributors (D1,D2) and five retailers (R11, R21 under distributor D1 and R12, R22, R32 under distributor D2). The parameter values are taken as a11=160, a21=155, a12=156, a22=150, a32=152, P=200,b=0.4, θ=5, c=50.

For these parameter values, the optimal non-negative wholesale price ranges of the manufacturer for the distributors D1 and D2 are respectively as (0.3406,.9075) and (0.3468,0.912). Therefore, for any α>0.9075 and α>0.912 the wholesale price of the manufacturer for the distributors D1 and D2 are negative. Fig. 2 justifies this result. Also, it depicts that the wholesale prices of the manufacturer for the distributors decrease with increasing CSR. Fig. 3 shows that the pure profit range of the manufacturer decreases, whereas total profit range of the manufacturer increases with increasing CSR. Also, α1_=0.3542 and α1¯=0.8432. Thus, for any α>0.8432, the pure profit of the manufacturer is negative. Note that α11d=0.912, α21d=0.935, α21d=0.9432, α22d=0.9391 and α32d=0.9375. Fig. 4 describes that the wholesale prices of the distributors for their retailers decrease and become negative with the manufacturer's increasing CSR. Also Fig. 5 shows that the distributors’ profits are inversely propositional to the manufacturer's CSR.

In Fig. 6, it is observed that ϕij and μj decrease with increasing CSR of the manufacturer. The intuitive reason is straightforward. When the manufacturer increases it is CSR, the downward wholesale prices are reduced as a result upward revenue flows are increased. That is, the upstream channel members reduce their wholesale prices and claim more revenues from their downstream channel members. It is a common practice, in a socially responsible supply chain that the leader of the channel is mainly responsible for CSR and it introduces code of conduct such that all the other channel members’ business practices are socially responsible. As such, in response to the manufacturer's reduced wholesale price, the distributors also reduce wholesale prices to encourage the retailers to sell more units by reducing retail prices. The distributors’ wholesale prices are inversely proportional to the manufacturers CSR intensity. Thus, when the manufacturers CSR intensity increases, the distributors’ wholesale prices may be less than the manufacturers marginal production cost and may be negative for the manufacturer's heavy CSR practice. That is, the distributer pays the retailer to sell units additional to decentralized order quantity. Finally, to exhibit CSR, the retailers’ sell the products at centralized prices. In such, the distributors and the retailers’ business practices are socially responsible. As the retailers’ sale the product at the centralized prices, their sales volumes increase and they earn more profits. To compensate the loss of revenues due to reduced wholesale prices, the retailers’ transfer fractions of revenues to their respective distributors. In turn, the distributors also transfer some revenues to the manufacturer. Since, for the higher emphasis on CSR, the reductions on wholesale prices are higher, the downstream channel members’ revenue transfers in reverse order are higher due to higher profit gains.

6Summary and concluding remarksIn this paper, we have proposed a RS contract to coordinate a socially responsible three-echelon distribution channel that consists of a manufacturer, multiple distributors and multiple retailers under each distributer. Following the common practice in industry, we have assumed that, in the primary firm, the manufacturer exhibits CSR and influences the other firms to perform socially through a code of conduct. In our formulation of the model, we have incorporated only the effect of CSR in the form of consumer surplus in the socially responsible firm's profit function rather than the activities which the channel performs. The proposed model yields following insights. First, it is found that, in a decentralized three-echelon distribution channel, all the channel members earn more profit when the manufacturer is more socially responsible. Moreover, consumers are also benefited for increasing CSR of the manufacturer because selling price of the product decreases when the manufacturer increases his/her CSR. Second, it is found that the RS contract coordinates the channel. It is also showed that, the RS contract cuts out channel conflict and leads to win–win outcomes for the channel members. Third, the wholesale prices under the RS are different compared to the wholesale prices of a traditional supply chain. The wholesale price of the manufacturer is less than zero above a threshold of CSR practice, i.e., it pays the distributor to sell additional units that it produces for exhibiting CSR. Even the manufacturer's pure profit becomes negative for its heavy CSR activity. The consumer surplus, which the manufacturer accrues, compensates the loss of pure profit.

Although the proposed model provides some insightful results, still it has some limits. First, for simplicity of analysis the demand is assumed as deterministic and linear function of price. Models may be developed by considering some stochastic price dependent demand or some other well established deterministic demand. Second, it is assumed that the manufacturer practices CSR. Instead of it, all the channel members may be involved in CSR and may perform it with a proportion.

The profits of the ijth retailer, the jth distributor and the manufacturer in the proposed mechanism must be greater than or equal to their respective decentralized profit. That is, πijr/rs>πijr*, πjd/rs>πjd* and vm/rs>vm*. From first inequality, we have

Decentralized profit of the jth distributor and decentralized total profit of the manufacturer corresponding to the ijth retailer are given by

On the other hand, profit of the jth distributor and total profit of the manufacturer corresponding to the ijth retailer under RS contract are given by

πijd/rs and vijm/rs are the profit segment of the jth distributor and the manufacturer under RS contract, while πijd* and vijm* are the profit segment of the jth distributor and the manufacturer under decentralized scenario corresponding to the ijth retailer. Each profit segment under RS contract must be greater or equal to the corresponding profit segment under decentralized scenario and thus overall profit under RS contract will be greater or equal to the overall profit under decentralized scenario. Now from the inequalities πijd/rs≥πijd* and vijm/rs≥vijm*, we have

Using the inequality (A.6) in (A.7), we get the maximum value of φij as

From (A.6), we will get the minimum value of μij when φij=φij¯ and is given by

Thus,

Similarly, from (A.7), we will get the maximum value of μij when φij=φij_ and is found as follows

Thus,

Hence, if φij∈φij_,φij¯ and μij∈μij_,μij¯ for i=1,2,…,nj;j=1,2,…,n, then the RS contract not only can be successfully implemented to coordinate the channel but also it provides win–win opportunity to the channel members. From (16) and (18) win–win range of wholesale price of the jth distributor and the manufacturer corresponding to the ijth retailer are found as follows

where Tij=(aij+θP)−(b+θ)c.