Negative symptoms, such as apathy and diminished motivation, are critical for prognosis and treatment outcomes in neurological and psychiatric disorders. However, constructs and assessment scales differ significantly across neuropsychiatric disorders. This study examines the psychometric properties of two scales used to assess apathy – the apathy-motivation index (AMI) and the diagnostic criteria for apathy (DCA) – compared to schizophrenia-specific tools, namely the brief negative symptoms scale (BNSS) and the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS).

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional, multicenter study with 151 individuals with schizophrenia across six European sites. Participants were assessed using the AMI, DCA, BNSS, PANSS, and other clinical and functional scales. BNSS motivation and pleasure factor (BNSS_MAP) assessed motivation, and personal and social performance (PSP) assessed functioning. Convergent validity across these tools was examined through bivariate correlations (Pearson r) and exploratory factor analysis for the AMI. Cut-off points for apathy used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, with DCA as the reference.

ResultsWe found low convergence between BNSS_MAP and AMI (r=.31, p<.001) and moderate convergence between BNSS_MAP and DCA (r=.48, p<.001). PSP correlated with BNSS_MAP, PANSS_negative and DCA (r=−.615, r=−.446 and r=−.430, respectively, all p<0.001), but not with AMI (r=−.108; p=.218). ROC analysis yielded cut-off points of 28.5 (BNSS total), 16.5 (BNSS_MAP), 14.5 (PANSS_negative), and 33.5 (AMI total) for detecting clinical apathy.

ConclusionCurrent apathy and motivation scales show limited overlap, reflecting the complexity of measuring transdiagnostic constructs. Combining clinician- and patient-rated measures may provide a more comprehensive understanding of apathy in schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric conditions.

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia are becoming conceptualized as a transdiagnostic phenomenon seen in several neuropsychiatric disorders.1 However, there has been limited effort to find common rating scales and terminology that could promote transdiagnostic research and interdisciplinary collaborations.2

Negative symptoms are core features of schizophrenia, associated with poor long-term prognosis and present a major unmet need for both pharmacological and non-pharmacological intervention.3 It is now widely accepted that negative symptoms involve five symptom domains, namely anhedonia (lack of pleasure experience), asociality (diminished interest in social interaction), avolition (difficulty in starting and maintaining goal-directed actions), blunted affect (diminished emotional expression), and alogia (reduction in word production).4 These five domains are further categorized into two dimensions. The motivation-and-pleasure (MAP) or experience dimension includes the anhedonia, asociality, and avolition domains. The emotional expression (EXP) dimension has been defined as the sum of blunted affect and alogia. Novel scales, such as the brief negative symptoms scale (BNSS)5 and the clinical assessment interview for negative symptoms (CAINS),6 were developed using this framework, aiming to replace the use of the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS)7 to achieve a more accurate assessment of what is currently considered the underlying constructs of the negative symptoms.

In parallel with the development of these novel assessment tools in the schizophrenia field, there is growing interest in a transdiagnostic approach.1 For instance, a lack of interest in social or goal-directed activities is a key symptom in depression (both bipolar disorder and unipolar depression), neurodegenerative disorders (Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and others), and even in the general population, which is emphasized in the dimensional psychiatry approach.8 However, the terminology used and the clinical rating scales significantly differ between disorders and disciplines. Apathy, a clinical syndrome characterized by a reduction in self-initiated, goal-directed activity that is not driven by a primary motor or sensory impairment,9,10 is a commonly used term in depression and dementia but is not mentioned as such in the BNSS or CAINS.

Two novel tools have been used for measuring apathy and its components in neuropsychiatric disorders. First, a group of experts updated the diagnostic criteria of apathy (DCA) in neurodegenerative disorders11, which is a clinician-rated categorical scale. The scale builds on novel approaches to the construct of apathy, not limited to observed behaviour, and categorizes apathy as the presence of at least two out of three major components, namely behaviour and cognition (‘loss of or diminished goal-directed or cognitive activity’), emotion (‘loss of or diminished emotion’), and social interaction (‘loss of or diminished engagement in social interactions’). Second, the apathy-motivation index (AMI)12 is a self-rated continuous scale with 18 items, developed in healthy volunteers but potentially usable as a transdiagnostic scale. Moreover, the AMI has three factors: behavioral activation (‘tendency to self-initiate goal-directed behaviour’), social motivation (‘level of engagement in social interactions’), and emotional sensitivity (‘feelings of positive and negative affection’).

In this study, our main aim was to explore whether non-schizophrenia scales for quantifying (AMI) and categorizing (DCA) apathy, measure a similar motivational construct as schizophrenia-based scales, such as BNSS_MAP or PANSS_negative. We did not define a gold standard measure; instead, we adopted a theory-neutral approach, using convergent validity to examine whether the scales that are theoretically expected to correlate are indeed related. The study had other secondary aims, including (a) comparing clinician-rated outcome measures (CROM) and patient-rated outcome measures (PROMs) for the same construct, (b) exploring the factor structure of AMI, which has not been used before in schizophrenia, and (c) finding cut-off points for clinically significant apathy in schizophrenia. Currently, PANSS, AMI, and BNSS (total or MAP) have no cut-off points for pathological apathy. We used DCA dichotomous classification to explore these cut-off points.

Material and methodsDesignCross-sectional multi-site trans-national non-interventional descriptive study.

Sites and recruitmentSix sites participated in this project: Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (Barcelona; Spain), University of Cambridge (United Kingdom), Università della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli (Italy), University Côte d’Azur (France), Université de Genève (Switzerland) and University of Rennes (France). All sites obtained independent local ethical approval for conducting the studies, with another overarching ethical approval (Cambridge; REC reference 20/EM/0230) for the coordinating site that analysed the data. The study was named CASES, namely Criteria of Apathy in Schizophrenia – a European Study.

PopulationThe inclusion criteria were aimed to be representative of people diagnosed with schizophrenia: (1) MINI criteria for schizophrenia (ICD-10 F20.XX) for >1 year; (2) age 18–60 years; (3) antipsychotic monotherapy or single antipsychotic augmentation; (4) outpatient setting; (5) no change in antipsychotic, antidepressant, or mood stabilizer in the previous 4 weeks; (6) no comorbid neurological or major psychiatric disorders recorded in the clinical notes; (7) no active use of illegal substances or criteria of abuse/dependence/harmful use of alcohol by clinical interview; and (8) preserved capacity to consent to participate.

AssessmentsBasic sociodemographic and clinical data were collected using a common case report form. The specific assessments included:

- 1.

M.I.N.I.: The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview13 is a brief, structured diagnostic tool used to assess and diagnose psychiatric disorders according to DSM and ICD criteria.

- 2.

2018 DCA: diagnostic criteria for apathy,11 a categorical scale (yes/no) assessing the presence of apathy in at least two out of three major components, namely behavioral and cognition (criteria B1 or DCA_B1), emotion (criteria B2 or DCA_B2), and social interaction (criteria B3 or DCA_B3).

- 3.

AMI: the apathy and motivation index12 is an self-rated 18-item scale with three factors: behavioral activation (BA), social motivation (SM), and emotional sensitivity (ES).

- 4.

PANSS: positive and negative syndrome scale.7 Gold standard scale for measuring psychopathology in schizophrenia, with 30-items covering positive (7), negative (7) and general psychopathology (16) dimensions. It uses a 7-point scale from 1 (=absence) and 7 (=extreme). PANSS-negative symptoms were the sum of seven negative items. In supplementary results, we also used alternative PANSS-derived factors such as Marder.14

- 5.

BNSS: brief negative symptoms scale.5 It covers 5 domains and 2 dimensions (MAP and EXP), as described in the “Introduction” section. For this study on motivation, BNSS_MAP was considered as the main BNSS variable.

- 6.

BACS: brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia15 is a standardized test designed to evaluate cognitive function in individuals with schizophrenia. It assesses key cognitive domains such as verbal memory, working memory, motor speed, attention, and executive function. Gender and age-adjusted z-scores were obtained.

- 7.

CDS: Calgary depression scale.16 A 9-item scale from 0 to 3, specifically developed for measuring depression in schizophrenia and widely used, with a cut-off point for clinical depression of 6.

- 8.

SHRS: St. Hans rating scale for extrapyramidal symptoms.17 A clinical tool used to assess extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) in patients taking antipsychotic drugs. Through a structured rating system, it evaluates the severity and presence of EPS, such as parkinsonism, dystonia, dyskinesia, and akathisia.

- 9.

PSP: personal and social performance scale.18 It measures the social functioning of individuals with mental disorders, particularly schizophrenia. It evaluates four key areas: socially useful activities, personal and social relationships, self-care, and disturbing and aggressive behaviours. The scores range between 0 and 100 (greater for better functioning).

AMI was the only self-rated scale (PROM), whereas all others were clinician-rated (CROM). Two independent clinicians rated the scales: one rated PANSS and BNSS, while the other rated DCA. Any clinician could rate the remaining scales, as these did not evaluate overlapping constructs. Before recruitment started, coordination, harmonisation, and training for using the scales were conducted online. Scoring was done as reported in the original publications for each scale.

Statistical analysisTo measure construct validity, we explored the convergent validity as no scale was considered the gold standard. Convergent validity was assessed using Pearson correlation, the ‘r’ score of which ranges from 0 (complete lack of convergent validity) to 1 (perfect convergent validity, showing construct overlap). For DCA, as a dichotomic variable, we used Spearman ranked correlation.

An alpha of 0.05 was selected for significance.

The statistical approach for convergent validity encompassed three steps: first, we explored high-order correlations between the main constructs: BNSS_MAP, PANSS_negative, DCA, and AMI. Second, we explored the lower-order correlations between BNSS dimensions (MAP and EE), with DCA's three criteria (behaviour and cognition; emotion and social interaction), and AMI's three subscales (BA, SM, and ES). PANSS_negative was not included as it has no subscales. The DCA ‘emotional life factor’ did not strictly align with any specific BNSS factor, so we decided to use three different measures: BNSS_EE, BNSS_EE+BNSS_anhedonia, and BNSS_anhedonia.

Third, we used PSP to explore the correlation between motivation, negative symptoms and the level of function, using Pearson's correlation. Finally, we also explored external validation by correlating the PSP score with the total scores and sub scores of the different measures of apathy.

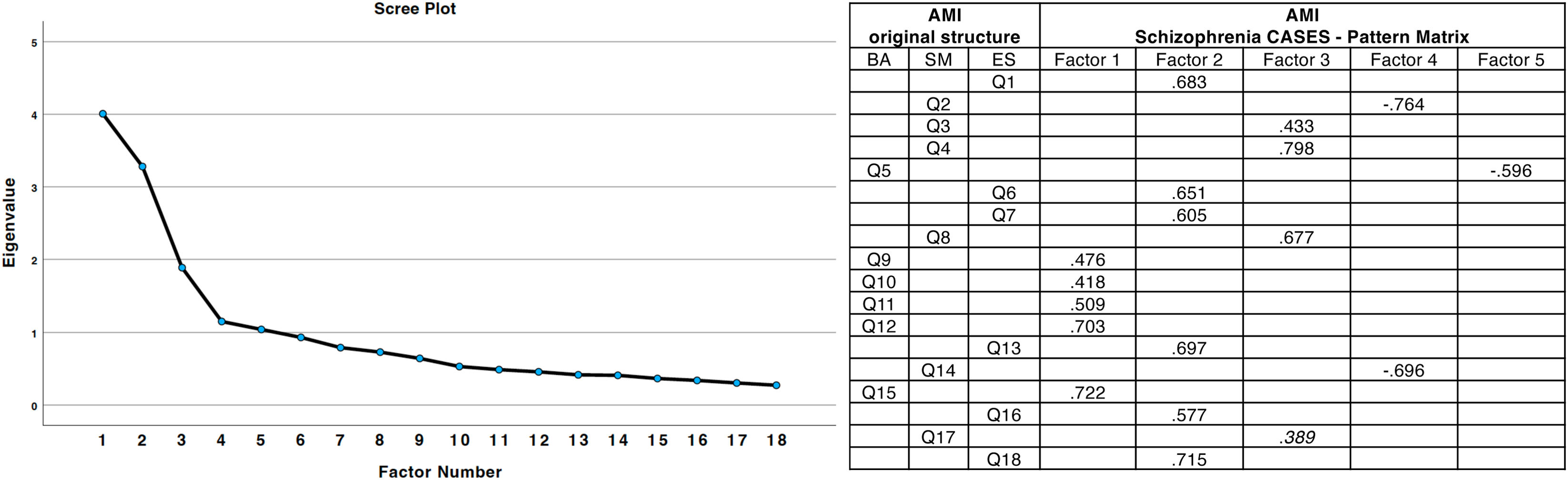

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on the AMI. The analysis used principal axis factoring (PAF) as the extraction method, which is suitable for non-normally distributed data. Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett's test of sphericity were conducted to confirm sampling adequacy. Factors were retained based on eigenvalues >1 and the inspection of the scree plot. Direct Oblimin rotation was applied to account for correlations between factors. The pattern matrix was used to interpret item loadings, with coefficients ≥0.4 considered significant.

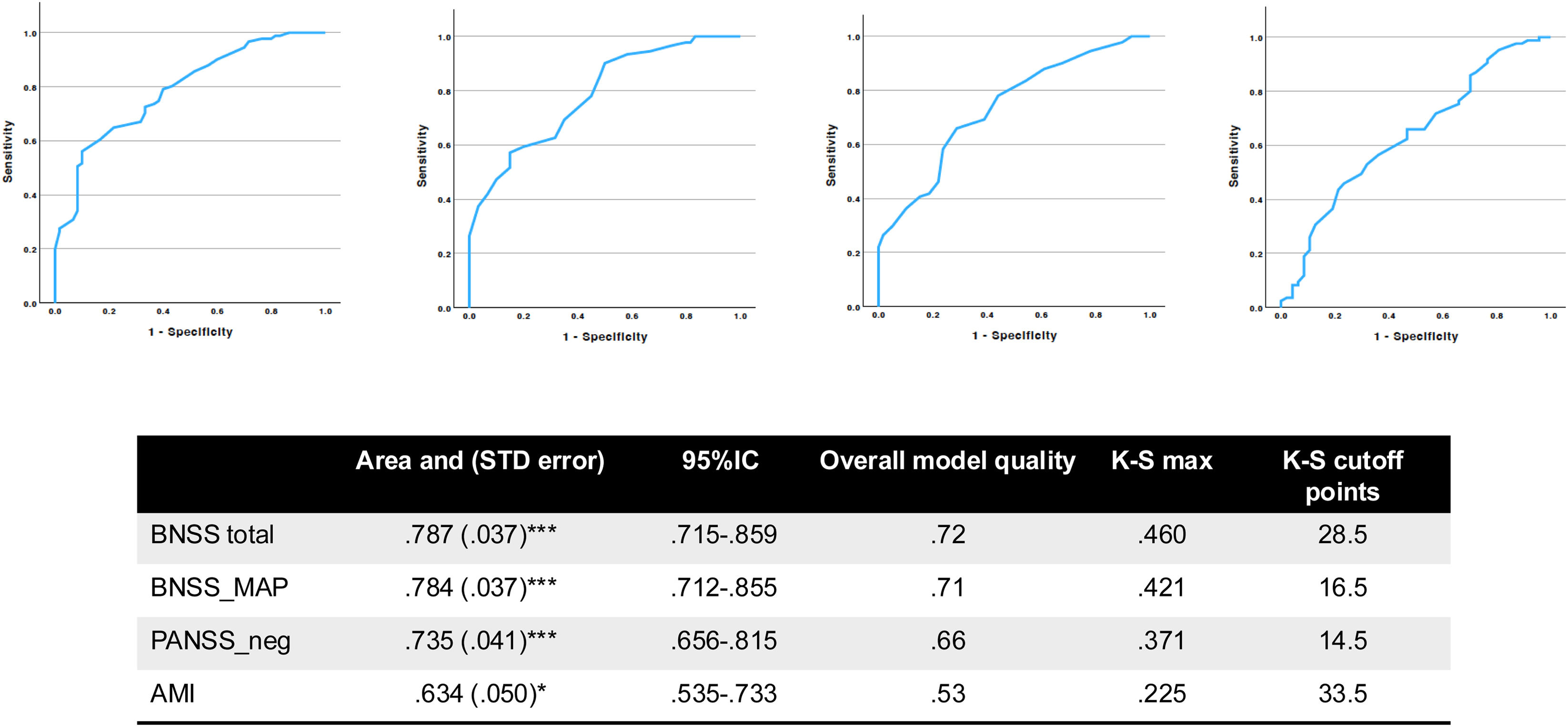

The discriminatory ability of the test variable was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to quantify the overall performance of the test in distinguishing between the two outcome groups (e.g., apathy vs. no apathy). The AUC ranges from 0.5 (no discrimination, equivalent to chance) up to 1.0 (perfect discrimination), with higher values indicating better test performance. Sensitivity and specificity values were computed for various cut-off points, and the optimal threshold was identified by maximising, which maximizes the sum of sensitivity and specificity (Youden's index). The statistical significance of the AUC was tested to determine whether the model performed better than random chance. DCA was used as a state variable against AMI, PANSS, BNSS total score, and BNSS_MAP.

All analyses used SPSS v29 (IBM, Chicago, 2024). Anonymized data and SPSS syntax for data analysis can be found at http://schizophrenias.group/publications/CASES [active after publication is accepted].

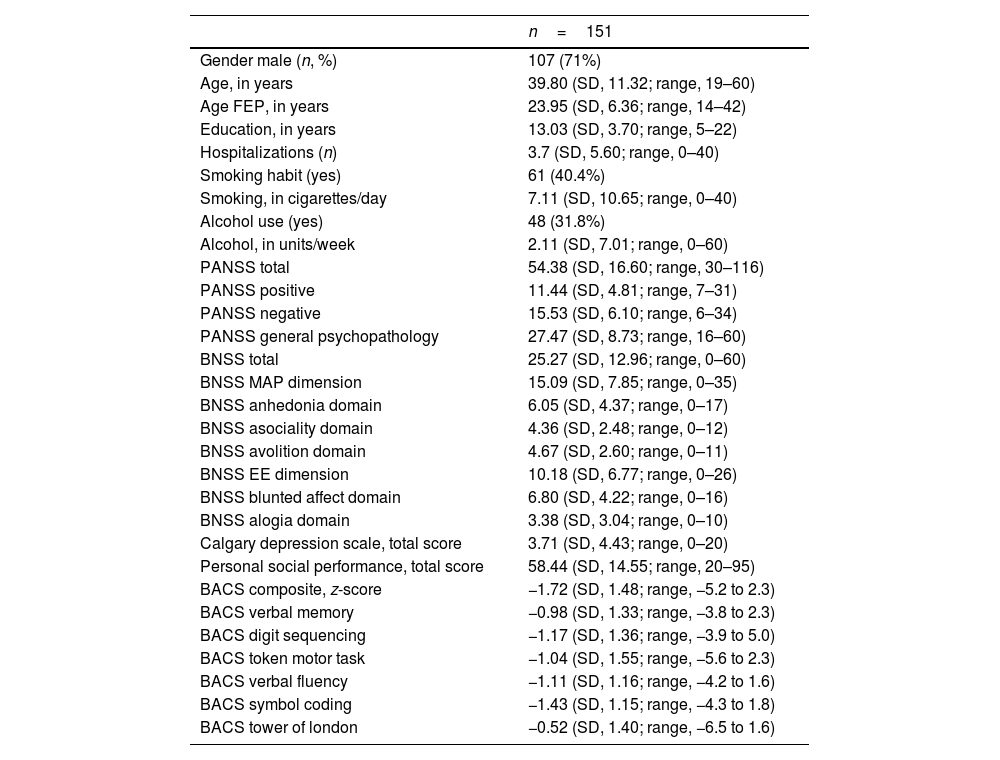

ResultsRecruitment took place from October 2020 through July 2023. A total of 151 volunteers were recruited. Table 1 illustrates the main sociodemographic and clinical variables commonly used in schizophrenia research. AMI was collected in 133 cases. Supplementary results 1 provides information on the sociodemographic data per site. Table 2 illustrates the psychometric scores of the two novel neuropsychiatric scales for measuring motivation in schizophrenia, the DCA and the AMI, and its subscores. The number of cases recruited (n=151) allowed to detect medium-sized correlations (r∼0.3) with a power >90 and significance of 0.05 for the main analysis.

Sociodemographics and clinical data of the sample. Number and percentage (in brackets) and mean and standard deviation (SD).

| n=151 | |

|---|---|

| Gender male (n, %) | 107 (71%) |

| Age, in years | 39.80 (SD, 11.32; range, 19–60) |

| Age FEP, in years | 23.95 (SD, 6.36; range, 14–42) |

| Education, in years | 13.03 (SD, 3.70; range, 5–22) |

| Hospitalizations (n) | 3.7 (SD, 5.60; range, 0–40) |

| Smoking habit (yes) | 61 (40.4%) |

| Smoking, in cigarettes/day | 7.11 (SD, 10.65; range, 0–40) |

| Alcohol use (yes) | 48 (31.8%) |

| Alcohol, in units/week | 2.11 (SD, 7.01; range, 0–60) |

| PANSS total | 54.38 (SD, 16.60; range, 30–116) |

| PANSS positive | 11.44 (SD, 4.81; range, 7–31) |

| PANSS negative | 15.53 (SD, 6.10; range, 6–34) |

| PANSS general psychopathology | 27.47 (SD, 8.73; range, 16–60) |

| BNSS total | 25.27 (SD, 12.96; range, 0–60) |

| BNSS MAP dimension | 15.09 (SD, 7.85; range, 0–35) |

| BNSS anhedonia domain | 6.05 (SD, 4.37; range, 0–17) |

| BNSS asociality domain | 4.36 (SD, 2.48; range, 0–12) |

| BNSS avolition domain | 4.67 (SD, 2.60; range, 0–11) |

| BNSS EE dimension | 10.18 (SD, 6.77; range, 0–26) |

| BNSS blunted affect domain | 6.80 (SD, 4.22; range, 0–16) |

| BNSS alogia domain | 3.38 (SD, 3.04; range, 0–10) |

| Calgary depression scale, total score | 3.71 (SD, 4.43; range, 0–20) |

| Personal social performance, total score | 58.44 (SD, 14.55; range, 20–95) |

| BACS composite, z-score | −1.72 (SD, 1.48; range, −5.2 to 2.3) |

| BACS verbal memory | −0.98 (SD, 1.33; range, −3.8 to 2.3) |

| BACS digit sequencing | −1.17 (SD, 1.36; range, −3.9 to 5.0) |

| BACS token motor task | −1.04 (SD, 1.55; range, −5.6 to 2.3) |

| BACS verbal fluency | −1.11 (SD, 1.16; range, −4.2 to 1.6) |

| BACS symbol coding | −1.43 (SD, 1.15; range, −4.3 to 1.8) |

| BACS tower of london | −0.52 (SD, 1.40; range, −6.5 to 1.6) |

FEP: index episode of psychosis; PANSS: positive and negative syndrome scale; BNSS: brief negative symptoms scale; BACS: brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia.

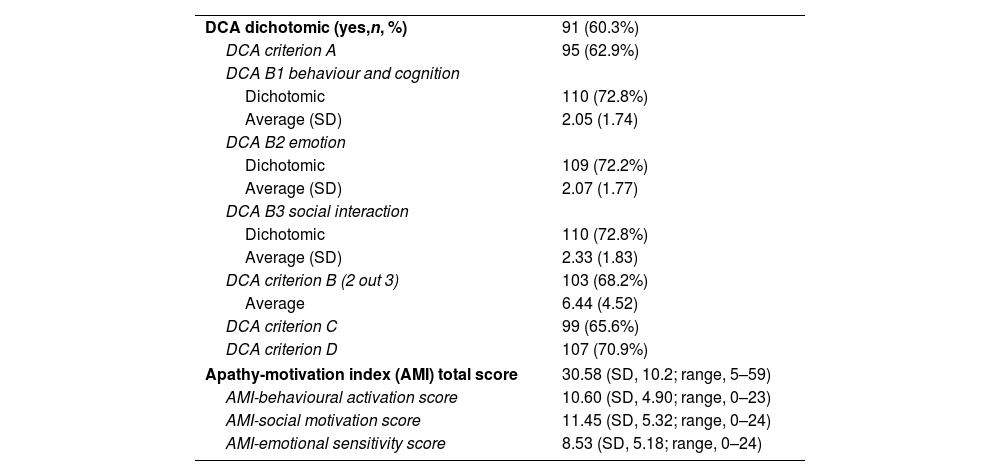

Novel scales used for measuring motivation. Number and percentage (in brackets) and mean and standard deviation (SD).

| DCA dichotomic (yes,n, %) | 91 (60.3%) |

| DCA criterion A | 95 (62.9%) |

| DCA B1 behaviour and cognition | |

| Dichotomic | 110 (72.8%) |

| Average (SD) | 2.05 (1.74) |

| DCA B2 emotion | |

| Dichotomic | 109 (72.2%) |

| Average (SD) | 2.07 (1.77) |

| DCA B3 social interaction | |

| Dichotomic | 110 (72.8%) |

| Average (SD) | 2.33 (1.83) |

| DCA criterion B (2 out 3) | 103 (68.2%) |

| Average | 6.44 (4.52) |

| DCA criterion C | 99 (65.6%) |

| DCA criterion D | 107 (70.9%) |

| Apathy-motivation index (AMI) total score | 30.58 (SD, 10.2; range, 5–59) |

| AMI-behavioural activation score | 10.60 (SD, 4.90; range, 0–23) |

| AMI-social motivation score | 11.45 (SD, 5.32; range, 0–24) |

| AMI-emotional sensitivity score | 8.53 (SD, 5.18; range, 0–24) |

DCA: diagnostic criteria of apathy; AMI: apathy-motivation index.

Age did not correlate with PANSS negative scores (r=−0.064, p=.44), BNSS total scores (r=−0.126, p=.123), or BNSS_MAP (r=−0.129, p=.115). It did correlate with AMI total score (r=−0.227, p=.009). Mean age differed significantly, though not clinically meaningfully, between those with apathy (38.1 years, SD, 11.0) and those without (42.4 years, SD, 10.9).

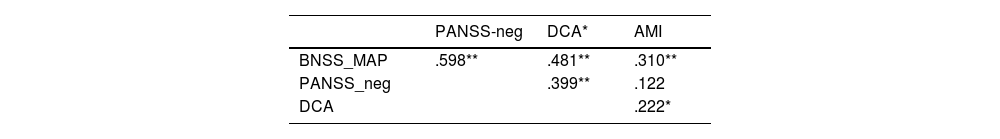

Convergent validityThe correlation between variables is summarized in Table 3a (for high order) and Table 3b (for lower order). Furthermore, for completeness, we correlated the PANSS-negative score with the BNSS total (r=.792; p<.001) and BNSS_EXP score (r=.725; p<.001). Supplementary results 1 shows the results using the PANSS Marder factor for negative symptoms, which were higher than with PANSS-negative scores.

High order – convergent validity. Using Pearson correlation for continuous variables and Spearmen correlation for dichotomic variables (DCA).

PANSS: positive and negative syndrome scale, negative syndrome; BNSS: brief negative symptoms scale, motivation and pleasure (MAP); DCA: diagnostic criteria of apathy; AMI: apathy-motivation index.

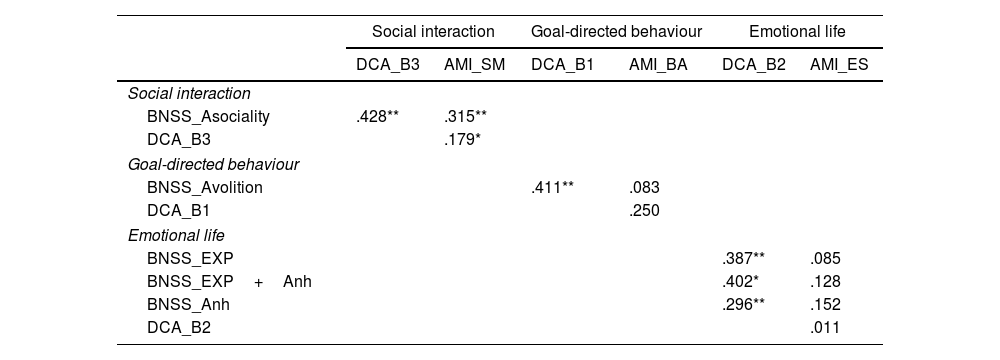

Lower order. Using Pearson correlation for continuous variables and Spearman correlation coefficient for dichotomic variables (DCA).

| Social interaction | Goal-directed behaviour | Emotional life | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCA_B3 | AMI_SM | DCA_B1 | AMI_BA | DCA_B2 | AMI_ES | |

| Social interaction | ||||||

| BNSS_Asociality | .428** | .315** | ||||

| DCA_B3 | .179* | |||||

| Goal-directed behaviour | ||||||

| BNSS_Avolition | .411** | .083 | ||||

| DCA_B1 | .250 | |||||

| Emotional life | ||||||

| BNSS_EXP | .387** | .085 | ||||

| BNSS_EXP+Anh | .402* | .128 | ||||

| BNSS_Anh | .296** | .152 | ||||

| DCA_B2 | .011 | |||||

PANSS: positive and negative syndrome scale, negative syndrome; BNSS: brief negative symptoms scale; EXP: emotional expression; Anh: anhedonia; DCA: diagnostic criteria of apathy; AMI: apathy-motivation index.

For completeness, high order correlations were performed with partial correction controlled by gender and age (see supplementary Table SS3a), with no significant differences with the direct correlation.

External validationWith high-order correlations, PSP was significantly correlated with BNSS_MAP (r=−.615, p<.001), PANSS_negative (r=−.446; p<.001) and DCA (r=−.430; p<.001) with no significant correlation with AMI (r=−.108; p=.218). In the low-order correlations, PSP significantly correlated with all BNSS and DCA-derived factors but with none of the AMI-derived factors (see supplementary material).

Exploratory factor analysis of AMIA Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of 0.78 and a significant Bartlett's test of sphericity (p<0.001) confirmed sampling adequacy. Five factors with eigenvalues >1 – including one single-item factor and another comprising two items – explained 63.1% of the total variance. The factor loadings preserved the overall structure of three main dimensions: behavioral, emotional, and social (Fig. 1).

Factor structure of the apathy-motivation index (AMI). The figure illustrates the original structure of the AMI and its factor loadings derived from schizophrenia cases. Factor loadings >0.4 are highlighted, indicating significant associations between items and specific factors. BA: behavioral activation; SM: social motivation; ES: emotional sensitivity. Positive and negative loadings reflect the direction of the relationship between items and latent constructs.

A total of 91 volunteers (60.3%) from our sample were categorized as having clinical apathy, measured with the DCA. Fig. 2 shows the total area under the curve, overall model quality, and cut-off points for BNSS_total, BNSS_MAP, PANSS_negative, and AMI_total of 28.5, 16.5, 14.5, and 33.5 points, respectively.

Area under the curve (AUC) for predicting apathy using different clinical measures. This figure illustrates the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves assessing the predictive accuracy of various clinical scales for diagnosing apathy. The analysis includes the diagnostic criteria for apathy (DCA) as the reference standard and evaluates the following measures: the brief negative symptom scale (BNSS) total score, the BNSS motivation and pleasure (BNSS_MAP) dimension, the positive and negative syndrome scale negative subscale (PANSS_neg), and the apathy-motivation index (AMI). The area under the curve (AUC), standard error (STD error), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), model quality, and corresponding Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K–S) statistics with cut-off points are presented. Significant predictive values are indicated with p<.05 (), p<.01 (), and p<.001 ().

All analyses were re-run separately for male and female patients (supplementary results 2). The main analysis of convergent validity (first and second order) showed similar results. However, cut-off points for clinically significant apathy differed among genders. To meet the criteria for apathy (DCA criteria), women showed higher threshold scores in BNSS_total (28.5 vs. 18.0), BNSS_MAP (20.5 vs. 9.5) and AMI (31.5 vs. 17.5) and similar for PANSS_neg (12.5 vs. 14.5).

DiscussionNo prior studies have compared BNSS dimensions with other CROM and PROM scales.2 We found that different measures of the same apathy/motivational construct had moderate to low convergent validity in people diagnosed with schizophrenia, suggesting scales might assess different facets of this construct. The lowest correlations were found between clinician and patient-rated outcome measures, whereas the different CROMs had moderate convergent validity. Our results are in line with previous research in schizophrenia and other fields, showing that scales had limited convergent validity,19 which decreased further when comparing CROM and PROM. The overarching implication is that scale choice might determine the study's outcome and success.

Regarding the strengths and limitations of our study, we used a multicentric, relatively large sample. However, it was culturally homogenous, as it was all based in Western Europe, and findings might need further replication with people outside this geographical area. While we aimed to recruit patients across all stages of the illness, the sample mainly included chronic schizophrenia. Nevertheless, negative symptoms are more prevalent in people with chronic schizophrenia3, and the goal of the study was to evaluate the convergent validity of the different scales. Still, we highlight that the prevalence of negative symptoms severity found is not representative of the broader schizophrenia spectrum disorder. The sample size was adequate to ensure sufficient power for the primary analysis, although it may have been limited for secondary analyses, such as determining cut-off points and assessing gender differences. The study was not preregistered, which represents an oversight; however, there were no deviations from the original study objectives.

In our sample, the BNSS total score had a good correlation with PANSS_negative symptoms (r=.74), similar to the initial study of BNSS psychometric properties (r=.8),5 and further replications in the Spanish (r=.71)20 and pan-European validation studies (r=.77).21 However, the BNSS motivation and emotional expression dimensions had a different profile. Compared with PANSS_negative, they correlated worse for BNSS_MAP (r=.598) and better for BNSS_EE (r=.725). A recent study22 using a much larger independent sample has shown that BNSS dimensions poorly predict PANSS-derived dimensions, demonstrating a similar pattern of lower predictive validity for MAP (r∼0.6) and higher for EE (r∼0.7). Considering the growing evidence that motivation and emotional expression are two independent dimensions with potentially distinct pathophysiology,23–25 our results add to the call for specific scales for both dimensions. Marder derived negative symptom factor (supplementary results) provided a slightly higher correlation (e.g., BNSS_MAP from .598 to .622) but still far from an optimal overlap.

BNSS and DCA also correlated poorly, with a high-order convergent validity <r=.5 and lower order (for individual domains) ranging from r=.38 to .43, suggesting they might measure different aspects of the same construct. DCA was not designed as a severity scale but to define dichotomously the presence of apathy, which might have affected its performance. Indeed, DCA's overall performance is better when considering its discriminatory value. As seen in Fig. 2, when DCA was used for dichotomous discrimination, BNSS total and MAP scores had acceptable discrimination (.7–.8) above PANSS_negative (.66; poor) and AMI_total (.53, almost no discrimination). This suggests that DCA might have a role in clinical settings as a screening tool for the presence of apathy in schizophrenia patients. Nevertheless, DCA has not been used in schizophrenia before, so the cut-off points found must be replicated in larger samples. Additionally, the cut-off points might help researchers categorise patients into those with and without clinically significant apathy, albeit this should be limited (and approached with caution) to those assessed with BNSS, as seen by the overall model quality scores (Fig. 2).

In our view, a revealing result was the poor correlation (sometimes non-significant) between the CROMs (BNSS, PANSS, and DCA) and the PROM (AMI). Furthermore, AMI was the only measure that did not significantly correlate with the level of functioning measured by the PSP. It is tempting to suggest that patients had less insight into their deficits than experienced researchers and clinicians, perhaps driven by cognitive deficits (mean BACS total z-score=−1.7). However, it is noteworthy that the AMI mean score (30.58) was much higher than those described in the general population, where the cut-off for severe apathy starts in the range of approximately 2.5 points,12 suggesting patients were not neglecting but very aware of their deficits. Whether this high AMI score is an overestimation or truly reflects the CROMs’ struggle to identify the severity of symptoms could not be elucidated with our study design. However, considering the lack of advancement in treating these symptoms and their subjectivity, our results add to the evidence supporting the need to add the patients’ views into the outcome measures in research studies,26,27 possibly combined with CROM to maximize the information about outcome.

In this study, we did not explore the impact of different sources of negative symptoms, such as depression or psychosis, motor symptoms, age or the influence of smoking as it was not the main aim of the project.28 We aim to explore the role of the different sources of negative symptoms in further projects. It is possible that different scales may be more sensitive to secondary sources, although this requires further investigation. Similarly, the present study focused on motivation rather than emotional expression, the other major dimension of negative symptoms.25 Future advances will likely incorporate ecological measures for assessing behaviours or activities in real-world, by using naturalistic settings rather than in controlled or artificial environments29,30. Such measures will capture how individuals interact with their surroundings in their everyday lives, providing a more accurate and contextualized understanding of activity patterns.

Our AMI factor analysis slightly differed from the original AMI scale in healthy volunteers (see Fig. 1). We found a total of five factors instead of the three reported by Ang et al.,12 but there are some considerations that should be taken into consideration. First, our sample size was considerably smaller than that of the initial study, which included over a thousand healthy volunteers. Second, the impression is that the structure of the factors did not vary excessively. AMI-ES and our factor two overlapped in their loading pattern. AMI-SM was the sum of our factors 3 and 4, and a closer exploration showed that questions in factor 3 were about passive social interaction and those in factor 4 concerned active social interaction, which might differ in people with schizophrenia. Lastly, five out of six items of the AMI-BA also loaded on our factor 1. Considering the AMI high score and the relatively stable factor structure, the use of PROMs for measuring apathy (negative symptoms) seems a promising avenue, as seen in other PROM measures, such as self-rated negative symptoms scales.2,3,31

Finally, if confirmed in larger samples, the higher cut-off points for BNSS and AMI in women to be categorized as clinically apathic might raise important questions about the lack of recognition of these symptoms in clinical practice. Gender differences in negative symptoms have not been extensively explored and might represent a relevant future line of research for its potential impact in personalization of interventions.

The overarching conclusion is the limited convergent validity between measures that assess similar constructs. Scales from similar conceptual approaches (schizophrenia-field derived PANSS and BNSS) had a higher correlation. The causes of the divergence are likely multifactorial (e.g., the subjectivity of the phenomena, emphasis on different aspects across the lifespan, etc.) but insist on the need for a new consensus on how complex subjective constructs are measured.29

Our work has shown the limitations of the current measures of motivation in schizophrenia. Future work should incorporate constructs from other research fields (e.g., neurodegeneration, affective disorders, and ageing, to name a few), as well as patients and carers. Ideally, the development of new scales should be guided by advances in the cognitive neuroscience of motivation and by emerging technologies capable of accurately assessing activity in real-world settings beyond the clinical environment.

FundingDr Fernandez-Egea is supported by the 2022 MRC/NIHR Clinical Academic Research Partnership (CARP) Award (MR/W029987/1). This research was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. NW was supported by an Israel Science Foundation Personal Research Grant (1603/22) and NSF-BSF-NIH Computational Neuroscience (CRCNS) grant (2024628). PBJ is supported by NIHR (PGfAR 0616-20003) and Wellcome, and is co-founder of Cambridge Adaptive Testing ltd. SK has been supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant No 10001CL_169783). GR is supported by the Fondation de l’Avenir (AP-RM-23-006, ET1-628) and the Fondation Planiol.

Conflicts of interestDD declared to have received support to attend meetings or served as an advisor or speaker for Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Teva. EFE declared to have received consultancy honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim (2022), Atheneum (2022) and Rovi (2022-24), speaker fees by Adamed (2022–24), Otsuka (2023) and Viatris (2024) and training and research material from Merz (2020) and editorial honoraria from Spanish Society of Psychiatry and Mental Health (2023–). SK declared to have received advisory board honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim and Exeltis as well as royalties for cognitive test and training software from Schuhfried. AMa declared to have received support to attend meetings or served as a advisor or speaker for Janssen Cilag, Neuraxpharm, Otsuka, Lundbeck and Angellini. AMu declared to have received advisory board or consultant fees from the following drug companies outside the submitted work: Angelini, Pierre Fabre, Rovi Pharma and Boehringer Ingelheim. SG declared to have advisory board/consultant fees or honoraria/expenses from the following pharmaceutical companies: Angelini, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gedeon Richter-Recordati, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Rovi Pharma. GMG has been a consultant for Angelini. The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.