Since only around 10% of people with gambling disorder (GD) seek professional treatment or attend self-help groups, multiple strategies are needed to improve this rate. The proposal of the Behavioral Addictions Center ‘Adcom’ (Madrid, Spain) is one such strategy, a pioneering and innovative program aimed at the general population to identify people with addictions such as GD, in an attempt to offer them appropriate evidence-based treatments.

Materials and methodsWe analyzed information obtained from the first 305 adults who voluntarily sought attention at Adcom for self-referred gambling, and conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional and observational study of this population.

ResultsA total of 265 of these 305 individuals were tagged as GD and were eventually included in the study, 87.2% of whom were men. The mean age of this sample was 36.9 years old and while 49.8% were treated for self-referred offline gambling addiction, the remaining 50.2% self-referred to online gambling addiction. Other psychopathological symptoms were evident in 57.4% of the participants, with a Global Severity Index T-score of 62.6 (± 12.2). Based on the SCL-90, depression (63.6%), psychoticism (62.6%), anxiety (66.7%) and obsession/compulsion (59.3%) were present in more than half of our participants, while 37.4% were diagnosed with ADHD. A multivariate regression analysis revealed that being born in Spain and excessive Internet use were independent predictors of online gambling addiction.

ConclusionsThis study of problem gamblers recruited in a non-clinical, self-referred setting confirms that GD is associated with an elevated presence of other mental disorders, identifying predictors of online and offline gambling addiction.

Interest in behavioral addictions has increased markedly in recent years among clinicians, researchers, and the general population,1 as reflected by the incorporation of gambling disorder (GD) as a “substance-related and addictive disorder” in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition, DSM-5),2 and the recognition of GD and “video gaming disorder” in the latest International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11).3 However, despite the clinical interest in other behavioral addictions, including excessive internet use,4 sex addiction5,6 and compulsive buying,6 these disorders are yet to be recognized in international classifications such as the ICD-11. To treat these conditions the first thing we need to do is identify affected individuals, which usually relies on clinical referral. It is estimated that only about 10% of individuals with gambling problems seek professional treatment for gambling disorder or attend self-help groups (e.g., Gamblers Anonymous), possibly owing to stigma, associated discrimination, and limited insight among those affected.7 Thus, novel strategies are needed to improve this figure, such as an innovative pioneering Behavioral Addictions Center (Adcom) program in Madrid (Spain). This centers targets the general population to identify more people with non-substance related addictions. People who believe they may be affected by such addictions can voluntarily attend Adcom for evaluation and treatment, as opposed to being referred by a general physician, and the data collected from them can be analyzed to better understand the addictions they suffer.

The Adcom program has been running for close to 3 years now and as a result, the data accumulated from those individuals with behavioral additions that have been treated at the center can now help us better define the profiles of this population. Of the behavioral addictions allocated to those evaluated at Adcom, GD is one of the most common. GD can be defined as “persistent and recurrent problematic gambling that leads to significant impairment or distress”.8 There has been a significant worldwide growth in gambling over recent years, in particular through online betting and the spread of the internet.9 For most patients, gambling is an activity that does not have negative consequences, however for a small proportion of individuals gambling negatively affects their emotional state, financial situation and relationships, with significant behavioral consequences. Thus, when GD develops in these individuals it should be rapidly identified, and they receive adequate support, treatment and protection. Hence, improving the options available to them and making them more readily available should become a health care priority.10

In the United States, GD has an estimated prevalence of 0.5% in the adult population,8 with comparable or slightly higher estimates in other countries.11 In Spain, data from 2022 indicate a prevalence of GD among 15–64 year olds of around 0.4%.12 Notably, epidemiological studies on people with GD also indicate a lifetime prevalence of other psychiatric disorders above 96%, without considering personality disorders.13 Mental disorders such as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), mood disorders or impulse-control disorders, or substance use disorders (SUDs) are common in GD patients,8,11,13–15 a situation known as gambling dual disorder (GDD), on which we believe the clinical spotlight should focus given its high prevalence.8,11,13,15,16 The significance of GDD is evident through the enhanced severity when GD is detected in individuals with ADHD that persists into adulthood relative to those without ADHD,17 and the worse prognosis in this population.18

The growth of online gambling in recent years has sparked interest in the possible clinical relevance of online as opposed to traditional offline/land-based gambling addiction, although few differences have been identified.19,20 However, the growing opportunities for online gambling, and its inherent availability, accessibility and anonymity, has generated concern that it may be more troubling than offline gambling for vulnerable individuals.15,21 Hence, we set out to better understand the sociodemographic, clinical and psychopathological characteristics associated with GD in the general population by analyzing the data obtained through the novel Adcom program. We conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional and observational study of this population, defining the profile of individuals with GD, and identifying factors that may influence the development of online or offline GD among them. This information will be of interest not only to identify individuals with GD and offer them appropriate treatment but also, to identify individuals at risk of developing GD prior to the onset of this condition.

Materials and methodsStudy design, participants and procedureWe conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional and observational study with individuals voluntarily attending AdCom (https://www.comunidad.madrid/servicios/salud/adcom-madrid), part of the Institute for Psychiatry and Mental Health at the Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón (Madrid, Spain), associated with the Madrid Public Health Service. Individuals who suspect gambling-related problems or other behavioral addictions in themselves or a close relative may seek evaluation at Adcom to determine whether the behavior meets criteria for addiction. The service is only accessed by self-referral, and the evaluation lasts approximately 1h, responding to questionnaires in the presence of a health care professional should assistance be required. If the results suggest addictive behavior, the individual is offered an appointment for further evaluation. This service can be accessed directly by anyone registered with the Community of Madrid Health Service through a self-appointment system (https://citawebadcom.sanidadmadrid.org/Acceso/Servicio.aspx).

All participants in this study sought attention for a self-referred potential gambling addiction from July 2022 to August 2024. The criteria for inclusion were: being at least 18 years old; requesting an AdCom appointment for a possible gambling-related behavioral addiction; and providing written informed consent. The exclusion criteria included the presence of an organic mental disorder (including cognitive impairment), mental retardation, or insufficient proficiency in the Spanish language that might impede understanding the study goals or evaluation process. Data was collected from the individuals through an electronic platform and included in a database created with the SAS 9.4 statistical software suite (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Each participant's data was pseudonymized and all the subjects in this study (n=265) were categorized as pathological gamblers by both MULTICAGE-CAD 422,23 and the NORC DSM-5 Screening tool for Gambling Problems (NODS: Supplementary data)24.

All procedures used in this study were conducted in full compliance with the Helsinki Declaration on research involving humans. The study was approved by Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón Research Ethics Committee (Madrid, Spain).

Primary and secondary endpointsThe primary endpoint was to evaluate the sociodemographic, clinical and psychopathological characteristics of the individuals evaluated at Adcom for a self-referred gambling problem. Participants were administered a comprehensive battery of validated instruments to measure behavioral addictions, ADHD and other mental disorders or symptoms. All questionnaires were self-administered and data was collected as part of a standardized process to collect clinical information. The secondary endpoint was to identify predictive factors for online and offline gambling addiction.

Assessment instrumentsA variety of assessment instruments were used in this study (see Annex A for a detailed explanation of these tools). Addictive behaviors were evaluated using the validated Spanish version of the MULTICAGE-CAD 4 questionnaire, an instrument that examines different domains: alcohol abuse/dependency, SUDs, pathological gambling, compulsive buying, sex addiction, eating disorders, excessive internet use, and video game addiction. The NODS tool was used to measure problematic gambling according to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. ADHD was evaluated using the 6-item short version (part A) of the Adult Self-Report Scale version 1.1 (ASRS-v.1.1), based on the DSM-5-TR criteria for ADHD,25,26 a tool commonly used to predict ADHD in adults. The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R)27,28 is a widely used self-report questionnaire to measure current psychopathological symptomatology, including: Somatization, Obsession-Compulsion, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, Phobic Anxiety, Paranoid Ideation and Psychoticism. This scale also yields 3 global scores of psychological distress: a global severity index (GSI); a positive symptom distress index (PSDI); and positive symptoms total (PST). SCL-90-R raw scores are converted to standardized T scores using population-based norms.29 A T score≥63 is considered at risk.

Statistical analysisThe variables were analyzed globally, as well as considering offline or online gambling addiction independently. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or range, and the categorical ones as the absolute and relative frequencies. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess independent predictive factors of offline and online gambling addiction. The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline, and the scores derived from the different assessment instruments, were included in the model with an entry/stay criterion of 0.20/0.10. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were analyzed from logistic regression models. Statistical significance was established at p≤0.05 and all statistical analyses were performed using SAS® for Windows, release 9.4 or later (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

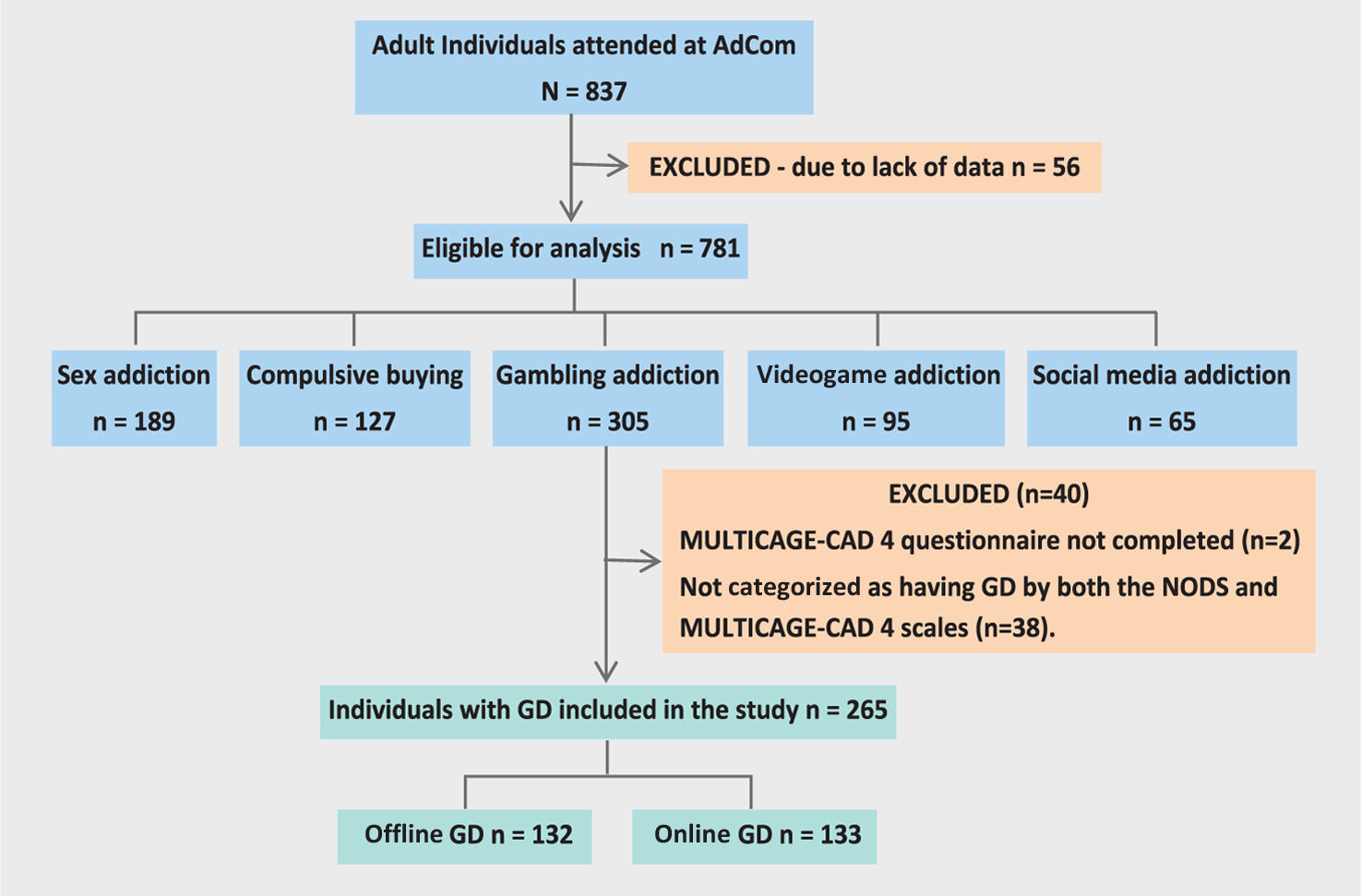

ResultsSocio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the participantsBy the time this study was conducted, Adcom had already treated 837 adults with a self-referred behavioral addiction, 56 of whom were excluded due to a lack of data. Of the remaining 781 individuals, 305 had a self-referred gambling addiction1 and after excluding 40 of them (Fig. 1), a total of 265 participants with GD were included in the study. Socio-demographic (Table 1) and clinical (Table 2) data from 265 individuals were entered into the Adcom database, of whom 132 (49.8%) self-identified offline gambling and 133 (50.2%) online gambling as their primary addiction (although the two modalities were not mutually exclusive).

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Characteristic | Total (N=265) | Offline gambling (N=132) | Online gambling (N=133) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (range) | 36.9 (18–84) | 43.4 (18–84) | 30.6 (18–70) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 34 (12.8%) | 27 (20.5%) | 7 (5.3%) |

| Male | 231 (87.2%) | 105 (79.5%) | 126 (94.7%) |

| Place of birth, n (%) | |||

| Spain | 224 (84.5%) | 100 (75.8%) | 124 (93.2%) |

| Other EU countries | 20 (7.5%) | 18 (13.6%) | 2 (1.5%) |

| Africa | 2 (0.8%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| America | 19 (7.2%) | 12 (9.1%) | 7 (5.3%) |

| Type of residence in the past 30 days, n (%) | |||

| House, flat, apartment | 262 (98.9%) | 130 (98.5%) | 132 (99.2%) |

| Other | 3 (1.1%) | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Life status, n (%) | |||

| Living with parents or family of origin | 116 (43.8%) | 50 (37.9%) | 66 (49.6%) |

| Living with partner | 48 (18.1%) | 21 (15.9%) | 27 (20.3%) |

| Living with partner and children | 46 (17.4%) | 21 (15.9%) | 25 (18.8%) |

| Living alone | 30 (11.3%) | 22 (16.7%) | 8 (6.0%) |

| Living with flatmates | 23 (8.7%) | 17 (12.9%) | 6 (4.5%) |

| Living in an Institution | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Educational level, n (%) | |||

| Illiterate | 3 (1.1%) | 3 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Primary education not completed | 10 (3.8%) | 8 (6.1%) | 2 (1.5%) |

| Primary education completed | 21 (7.9%) | 14 (10.6%) | 7 (5.3%) |

| Secondary education completed | 56 (21.1%) | 30 (22.7%) | 26 (19.5%) |

| Baccalaureate or intermediate vocational training | 98 (37.0%) | 51 (38.6%) | 47 (35.3%) |

| Higher education completed | 77 (29.1%) | 26 (19.7%) | 51 (38.3%) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| Actively employed (even on sick leave) | 165 (62.3%) | 66 (50.0%) | 99 (74.4%) |

| Working without being registered with the SS | 5 (1.9%) | 2 (1.5%) | 3 (2.3%) |

| Unemployed and not having worked before | 3 (1.1%) | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Unemployed having worked before | 41 (15.5%) | 25 (18.9%) | 16 (12.0%) |

| Permanently disabled (receiving benefits) | 26 (9.8%) | 23 (17.4%) | 3 (2.3%) |

| Home keeper | 3 (1.1%) | 3 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| In a different situation | 22 (8.3%) | 11 (8.3%) | 11 (8.3%) |

| Civil status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 148 (55.8%) | 64 (48.5%) | 84 (63.2%) |

| Married | 49 (18.5%) | 30 (22.7%) | 19 (14.3%) |

| Divorced | 10 (3.8%) | 9 (6.8%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Separated | 6 (2.3%) | 6 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| WidowedNon-marital partnership | 6 (2.3%) | 6 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| In a different situation | 46 (17.4%) | 17 (12.9%) | 29 (21.8%) |

EU, European Union; SS, social security.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the participants.

| Characteristic | Total (N=265) | Offline gambling (N=132) | Online gambling (N=133) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additional behavioral addiction, n (%) | |||

| None | 151 (57.0%) | 75 (56.8%) | 76 (57.1%) |

| Offline gambling | 39 (14.7%) | – | 39 (29.3%) |

| Online gambling | 40 (15.1%) | 40 (30.3%) | – |

| Videogaming | 7 (2.6%) | 5 (3.8%) | 2 (1.5%) |

| Excessive internet use | 10 (3.8%) | 2 (1.5%) | 8 (6.0%) |

| Compulsive buying | 11 (4.2%) | 6 (4.5%) | 5 (3.8%) |

| Sex | 7 (2.6%) | 4 (3.0%) | 3 (2.3%) |

| Current use of substances, n (%) | |||

| Tobacco | 118 (44.5%) | 64 (48.5%) | 54 (40.6%) |

| Alcohol | 113 (42.6%) | 52 (39.4%) | 61 (45.9%) |

| Cocaine | 12 (4.5%) | 7 (5.3%) | 5 (3.8%) |

| Heroin | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Cannabis | 19 (7.2%) | 9 (6.8%) | 10 (7.5%) |

| Anxiolytics or tranquillizers | 71 (26.8%) | 52 (39.4%) | 19 (14.3%) |

| Amphetamines | 2 (0.8%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Synthetic drugs | 2 (0.8%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Other | 5 (1.9%) | 4 (3.0%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Use of substances in the past year, n (%) | |||

| Tobacco | 145 (54.7%) | 75 (56.8%) | 70 (52.6%) |

| Alcohol | 149 (56.2%) | 69 (52.3%) | 80 (60.2%) |

| Cocaine | 28 (10.6%) | 13 (9.8%) | 15 (11.3%) |

| Heroin | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Cannabis | 46 (17.4%) | 16 (12.1%) | 30 (22.6%) |

| Anxiolytics or tranquillizers | 88 (33.2%) | 58 (43.9%) | 30 (22.6%) |

| Amphetamines | 8 (3.0%) | 5 (3.8%) | 3 (2.3%) |

| Synthetic drugs | 14 (5.3%) | 8 (6.1%) | 6 (4.5%) |

| Other | 7 (2.6%) | 5 (3.8%) | 2 (1.5%) |

| Prior consultation for a mental health disorder, n (%) | 139 (52.5%) | 82 (62.1%) | 57 (42.9%) |

| Current treatment for the mental health disorder, n (%) | 111 (41.9%) | 66 (50.0%) | 45 (33.8%) |

| Consequences of addiction | |||

| Familial | 242 (91.3%) | 119 (90.2%) | 123 (92.5%) |

| Financial | 256 (96.6%) | 125 (94.7%) | 131 (98.5%) |

| Emotional | 246 (92.8%) | 121 (91.7%) | 125 (94.0%) |

| Physical health | 139 (52.5%) | 76 (57.6%) | 63 (47.4%) |

| Academic or occupational | 131 (49.4%) | 63 (47.7%) | 68 (51.1%) |

| Leisure or entertainment | 186 (70.2%) | 94 (71.2%) | 92 (69.2%) |

| Social | 188 (70.9%) | 98 (74.2%) | 90 (67.7%) |

| Legal | 96 (36.2%) | 50 (37.9%) | 46 (34.6%) |

| Family history of similar problems related to gambling addiction, n (%) | 66 (24.9%) | 39 (29.5%) | 27 (20.3%) |

SD, standard deviation.

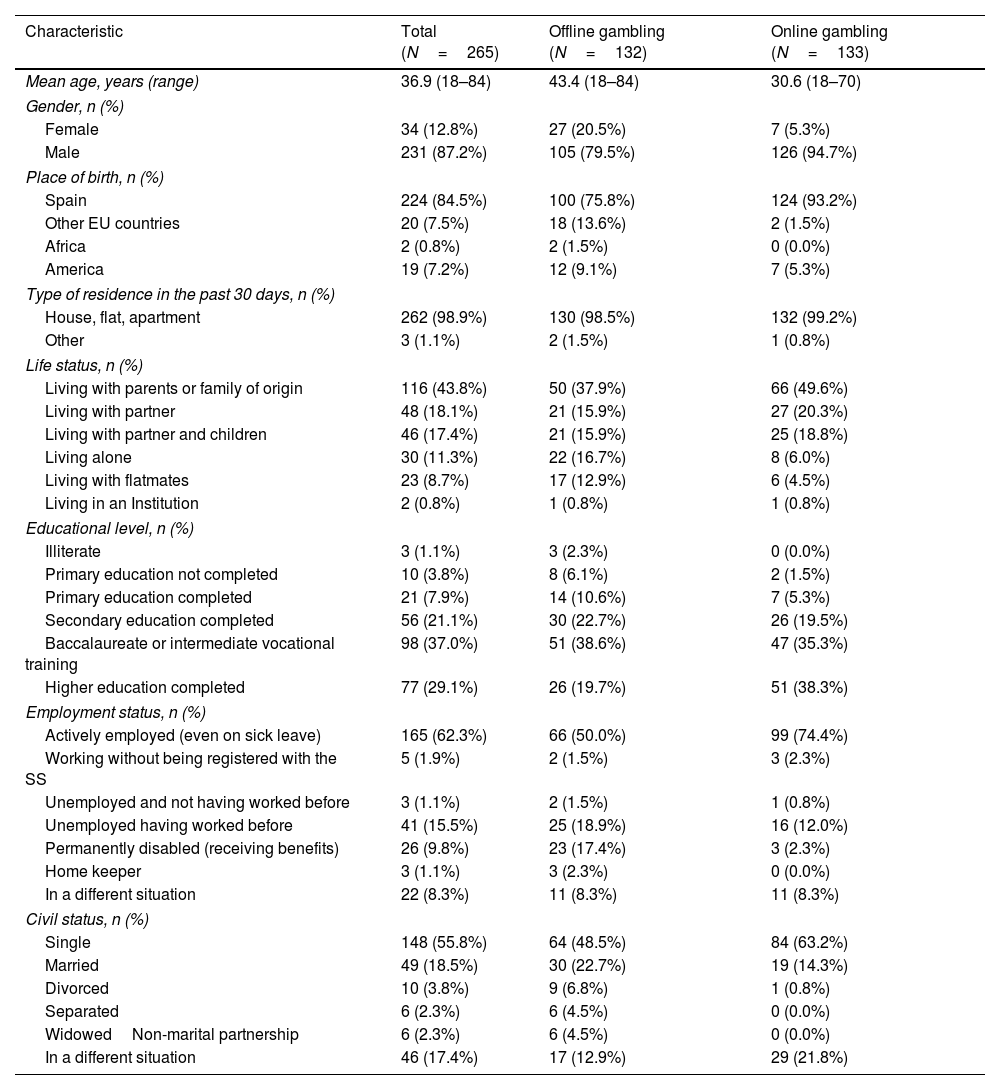

Most participants were men (87.2%), with a mean age of 36.9 years old (range, 18–84 years). The mean age of the group of individuals with a self-referred online gambling addiction was 30.6 years old (range, 18–70 years), while those with a self-referred offline gambling addiction were older (mean age, 43.4 years old; range, 18–84 years). Most participants were born in Spain (84.5%) and more than half of participants (56.2%) reside in metropolitan Madrid as opposed to other parts of the region (Autonomic Community of Madrid). More individuals reported being single (55.8%) or actively employed (62.3%), and 43.8% lived with their nuclear family of origin, 35.5% lived with their partner (with or without children) and 11.3% lived alone. In terms of education, 66.1% had undertaken studies beyond compulsory secondary education as their highest level of formal studies.

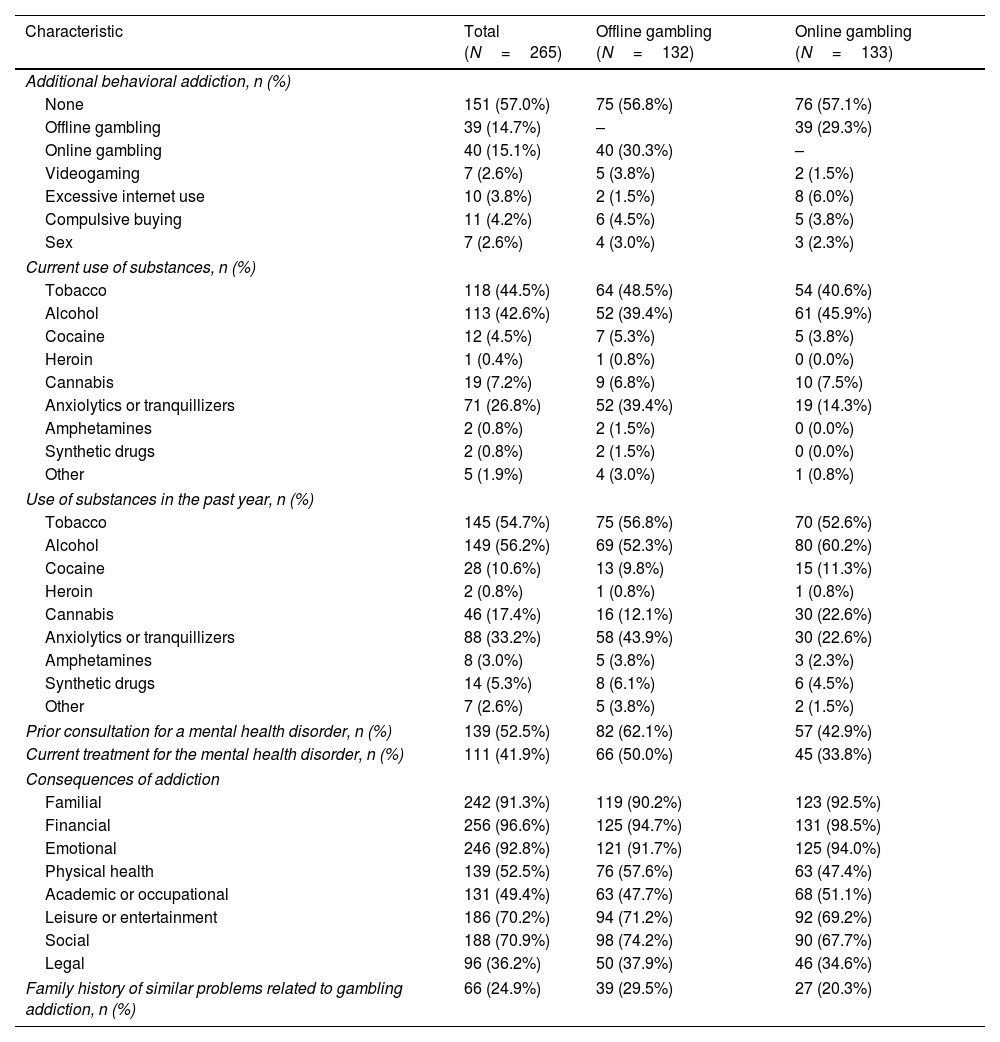

While more than half the participants (57.0%) reported having no additional behavioral addictions, 29.3% of the individuals with self-referred offline gambling addiction reported having a problem with online gambling too. Similarly, 30.3% of those with a self-referred online gambling addiction also reported having an offline gambling problem. Regarding substance use, 44.5% of the participants used tobacco at the time of the study, 42.6% used alcohol and 26.8% took benzodiacepines. In addition, a larger number of participants used substances in the past year for all substances assessed (Table 2). Approximately half the cohort (52.5%) had previously consulted a professional regarding a mental health problem, with this proportion being much higher among those with a self-referred offline (62.1%) as opposed to online (42.9%) gambling problem. Indeed, 41.9% of the participants were on therapy for such mental health problems at the time of the study. Regarding the consequences of addiction on the different areas of the participants’ life, an important financial impact was reported by most individuals (96.6%), followed by emotional (92.8%) effects and an impact on the family (91.3%). A total of 24.9% participants reported a family history of similar problems with gambling.

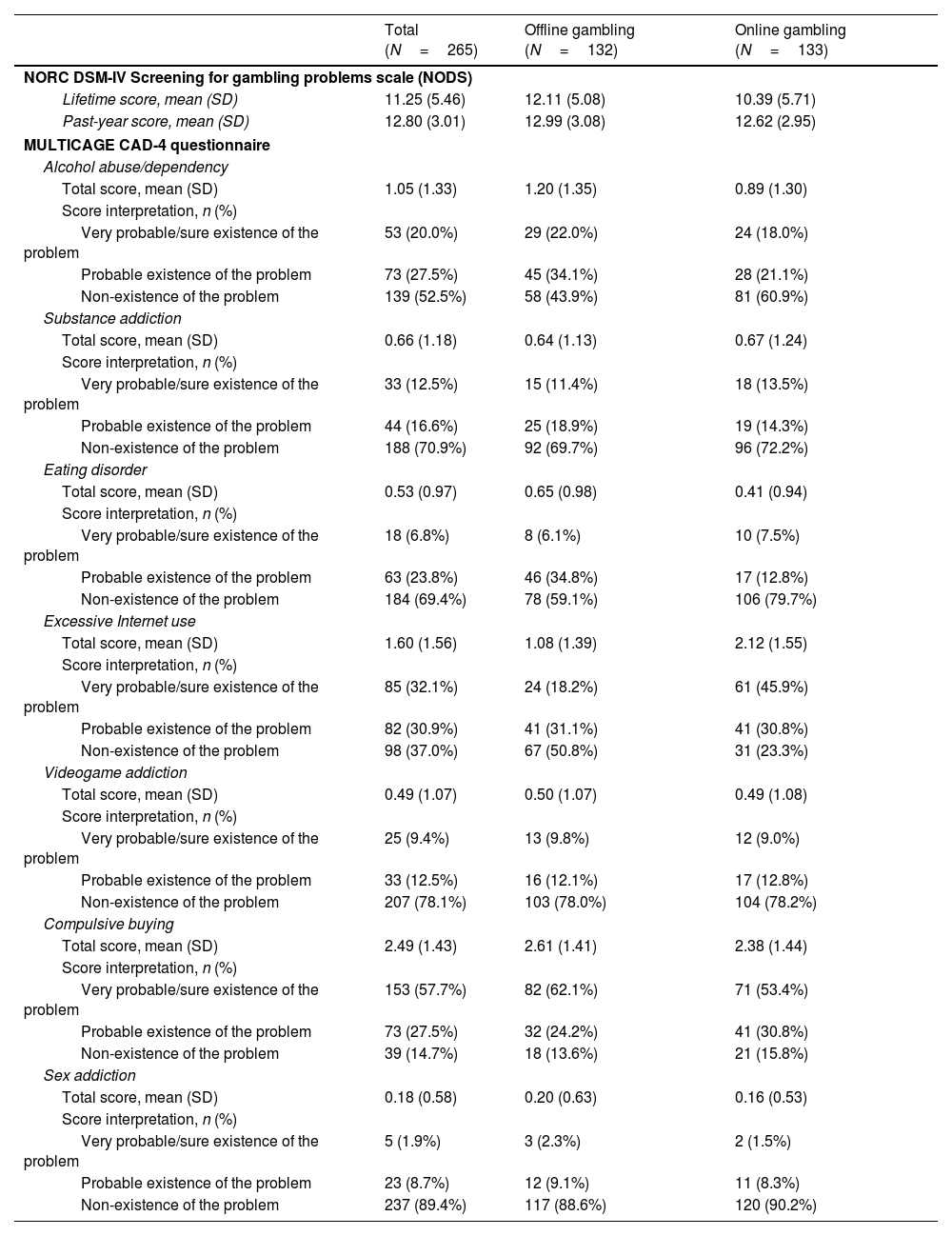

Clinical and psychopathological profile of the participantsThe mean total NODS score of the problem gambling sample was 11.25 (SD, 5.46) for the lifetime version and 12.80 (SD, 3.01) when considering the past-year. Similar results were obtained for self-referred offline and online gambling addiction (Table 3). The MULTICAGE-CAD 4 questionnaire identified the existence of other addictive behaviors assessed (Table 3). Compulsive buying was identified as a potential problem in the largest proportion of participants with GD (85.2%), the majority of whom very probably had this problem (57.7%). Furthermore, a large proportion of participants potentially indulged in excessive internet use (63.0%), more so those with a self-referred online (76.7%) than offline addiction (49.3%). Among the participants with very probable excessive Internet use (32.1%), a higher proportion referred to an online (45.9%) rather than an offline gambling (18.2%) addiction. Alcohol dependency was a potential problem in 47.5% of participants, and an eating disorder, substance use, video game or sex addiction was associated with 30.6%, 29.1%, 21.9% and 10.6% of the participants, respectively. Significantly, the proportion of participants with a potential eating disorder was twice as high in those with a self-referred offline gambling addiction (40.9% vs 20.3%; p<0.001), in whom alcohol dependency was also more of a potential problem than in those with a self-referred online gambling addiction (56.1% vs 39.1%; p=0.006).

Description of the participant's addictive behaviors.

| Total (N=265) | Offline gambling (N=132) | Online gambling (N=133) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NORC DSM-IV Screening for gambling problems scale (NODS) | |||

| Lifetime score, mean (SD) | 11.25 (5.46) | 12.11 (5.08) | 10.39 (5.71) |

| Past-year score, mean (SD) | 12.80 (3.01) | 12.99 (3.08) | 12.62 (2.95) |

| MULTICAGE CAD-4 questionnaire | |||

| Alcohol abuse/dependency | |||

| Total score, mean (SD) | 1.05 (1.33) | 1.20 (1.35) | 0.89 (1.30) |

| Score interpretation, n (%) | |||

| Very probable/sure existence of the problem | 53 (20.0%) | 29 (22.0%) | 24 (18.0%) |

| Probable existence of the problem | 73 (27.5%) | 45 (34.1%) | 28 (21.1%) |

| Non-existence of the problem | 139 (52.5%) | 58 (43.9%) | 81 (60.9%) |

| Substance addiction | |||

| Total score, mean (SD) | 0.66 (1.18) | 0.64 (1.13) | 0.67 (1.24) |

| Score interpretation, n (%) | |||

| Very probable/sure existence of the problem | 33 (12.5%) | 15 (11.4%) | 18 (13.5%) |

| Probable existence of the problem | 44 (16.6%) | 25 (18.9%) | 19 (14.3%) |

| Non-existence of the problem | 188 (70.9%) | 92 (69.7%) | 96 (72.2%) |

| Eating disorder | |||

| Total score, mean (SD) | 0.53 (0.97) | 0.65 (0.98) | 0.41 (0.94) |

| Score interpretation, n (%) | |||

| Very probable/sure existence of the problem | 18 (6.8%) | 8 (6.1%) | 10 (7.5%) |

| Probable existence of the problem | 63 (23.8%) | 46 (34.8%) | 17 (12.8%) |

| Non-existence of the problem | 184 (69.4%) | 78 (59.1%) | 106 (79.7%) |

| Excessive Internet use | |||

| Total score, mean (SD) | 1.60 (1.56) | 1.08 (1.39) | 2.12 (1.55) |

| Score interpretation, n (%) | |||

| Very probable/sure existence of the problem | 85 (32.1%) | 24 (18.2%) | 61 (45.9%) |

| Probable existence of the problem | 82 (30.9%) | 41 (31.1%) | 41 (30.8%) |

| Non-existence of the problem | 98 (37.0%) | 67 (50.8%) | 31 (23.3%) |

| Videogame addiction | |||

| Total score, mean (SD) | 0.49 (1.07) | 0.50 (1.07) | 0.49 (1.08) |

| Score interpretation, n (%) | |||

| Very probable/sure existence of the problem | 25 (9.4%) | 13 (9.8%) | 12 (9.0%) |

| Probable existence of the problem | 33 (12.5%) | 16 (12.1%) | 17 (12.8%) |

| Non-existence of the problem | 207 (78.1%) | 103 (78.0%) | 104 (78.2%) |

| Compulsive buying | |||

| Total score, mean (SD) | 2.49 (1.43) | 2.61 (1.41) | 2.38 (1.44) |

| Score interpretation, n (%) | |||

| Very probable/sure existence of the problem | 153 (57.7%) | 82 (62.1%) | 71 (53.4%) |

| Probable existence of the problem | 73 (27.5%) | 32 (24.2%) | 41 (30.8%) |

| Non-existence of the problem | 39 (14.7%) | 18 (13.6%) | 21 (15.8%) |

| Sex addiction | |||

| Total score, mean (SD) | 0.18 (0.58) | 0.20 (0.63) | 0.16 (0.53) |

| Score interpretation, n (%) | |||

| Very probable/sure existence of the problem | 5 (1.9%) | 3 (2.3%) | 2 (1.5%) |

| Probable existence of the problem | 23 (8.7%) | 12 (9.1%) | 11 (8.3%) |

| Non-existence of the problem | 237 (89.4%) | 117 (88.6%) | 120 (90.2%) |

SD, standard deviation.

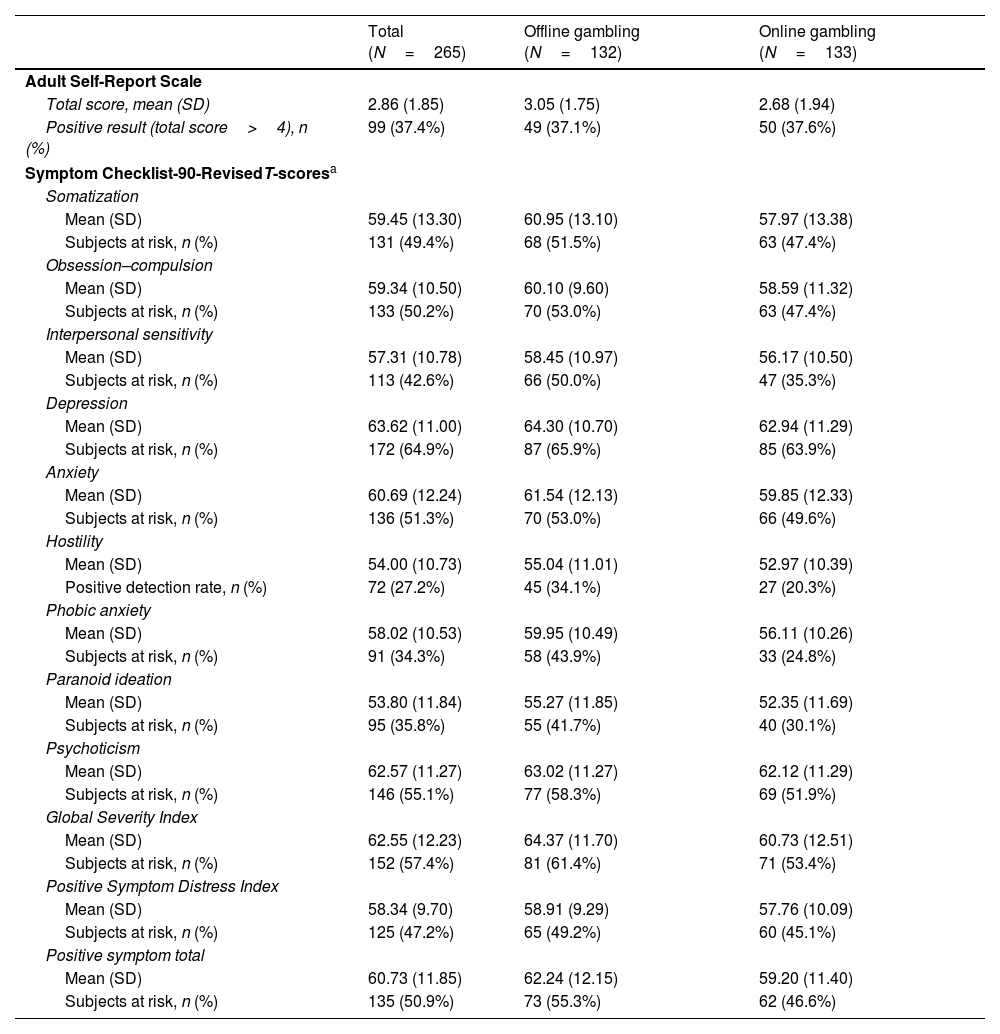

The mean total ASRS-v1.1 score was 2.86 (SD, 1.85) and 37.4% of the sample was considered positive for ADHD, with similar results for both offline and online gambling addiction (Table 4). According to the SCL-90-R, more than half of the participants (64.9%) experienced depression (mean T-score 63.6; SD, 11.0), psychoticism (55.1%; mean T-score 62.6, SD, 11.3), anxiety (51.3%, mean T-score 60.7; SD, 12.24) or obsession/compulsion (50.2%; mean T-score 59.3, SD, 10.5; Table 4). Somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation and hostility were evident in 49.4%, 42.6%, 34.3%, 35.8% and 27.2% of participants, respectively. This scale yields a mean GSI of 62.6 (SD, 12.2), with positive levels of psychopathological distress in 57.4% of participants. The PSDI and PST scores were 58.3 (SD, 9.7) and 60.4 (SD, 11.9), respectively (Table 4).

Incidence rate of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and psychopathological symptoms among participants.

| Total (N=265) | Offline gambling (N=132) | Online gambling (N=133) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Self-Report Scale | |||

| Total score, mean (SD) | 2.86 (1.85) | 3.05 (1.75) | 2.68 (1.94) |

| Positive result (total score>4), n (%) | 99 (37.4%) | 49 (37.1%) | 50 (37.6%) |

| Symptom Checklist-90-RevisedT-scoresa | |||

| Somatization | |||

| Mean (SD) | 59.45 (13.30) | 60.95 (13.10) | 57.97 (13.38) |

| Subjects at risk, n (%) | 131 (49.4%) | 68 (51.5%) | 63 (47.4%) |

| Obsession–compulsion | |||

| Mean (SD) | 59.34 (10.50) | 60.10 (9.60) | 58.59 (11.32) |

| Subjects at risk, n (%) | 133 (50.2%) | 70 (53.0%) | 63 (47.4%) |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | |||

| Mean (SD) | 57.31 (10.78) | 58.45 (10.97) | 56.17 (10.50) |

| Subjects at risk, n (%) | 113 (42.6%) | 66 (50.0%) | 47 (35.3%) |

| Depression | |||

| Mean (SD) | 63.62 (11.00) | 64.30 (10.70) | 62.94 (11.29) |

| Subjects at risk, n (%) | 172 (64.9%) | 87 (65.9%) | 85 (63.9%) |

| Anxiety | |||

| Mean (SD) | 60.69 (12.24) | 61.54 (12.13) | 59.85 (12.33) |

| Subjects at risk, n (%) | 136 (51.3%) | 70 (53.0%) | 66 (49.6%) |

| Hostility | |||

| Mean (SD) | 54.00 (10.73) | 55.04 (11.01) | 52.97 (10.39) |

| Positive detection rate, n (%) | 72 (27.2%) | 45 (34.1%) | 27 (20.3%) |

| Phobic anxiety | |||

| Mean (SD) | 58.02 (10.53) | 59.95 (10.49) | 56.11 (10.26) |

| Subjects at risk, n (%) | 91 (34.3%) | 58 (43.9%) | 33 (24.8%) |

| Paranoid ideation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 53.80 (11.84) | 55.27 (11.85) | 52.35 (11.69) |

| Subjects at risk, n (%) | 95 (35.8%) | 55 (41.7%) | 40 (30.1%) |

| Psychoticism | |||

| Mean (SD) | 62.57 (11.27) | 63.02 (11.27) | 62.12 (11.29) |

| Subjects at risk, n (%) | 146 (55.1%) | 77 (58.3%) | 69 (51.9%) |

| Global Severity Index | |||

| Mean (SD) | 62.55 (12.23) | 64.37 (11.70) | 60.73 (12.51) |

| Subjects at risk, n (%) | 152 (57.4%) | 81 (61.4%) | 71 (53.4%) |

| Positive Symptom Distress Index | |||

| Mean (SD) | 58.34 (9.70) | 58.91 (9.29) | 57.76 (10.09) |

| Subjects at risk, n (%) | 125 (47.2%) | 65 (49.2%) | 60 (45.1%) |

| Positive symptom total | |||

| Mean (SD) | 60.73 (11.85) | 62.24 (12.15) | 59.20 (11.40) |

| Subjects at risk, n (%) | 135 (50.9%) | 73 (55.3%) | 62 (46.6%) |

SD, standard deviation.

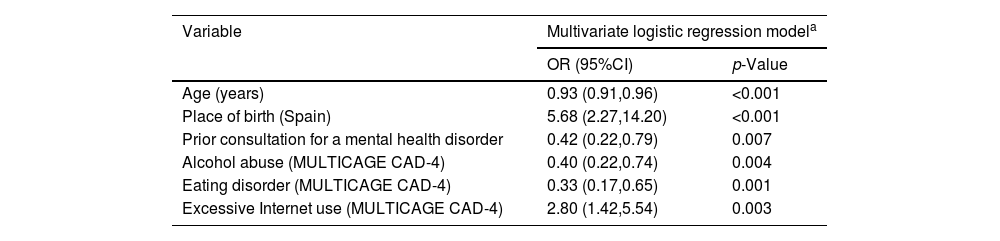

We conducted a multivariate analysis to identify predictors of offline and online gambling addiction (Table 5), based on the set of socio-demographic and clinical variables registered at baseline, and on the scores derived from the instruments used to assess the participants. Consequently, a higher risk for online gambling addiction was evident in participants born in Spain relative to those with offline GD (OR, 5.68; p<0.001; 95%CI, 2.27–14.20), as well as in those with associated excessive Internet use (according to MULTICAGE CAD-4: OR, 2.80; p<0.003; 95%CI, 1.42–5.54). Conversely, being older, having previously consulted a clinician for a mental health problem, having an eating disorder or an alcohol addiction all reduced the relative odds of an online gambling addiction. Relative to those individuals with offline GD, the odds of an online gambling addiction was reduced by 7% for each year increase in age (OR, 0.93; p<0.001; 95%CI, 0.91–0.96), by 60% in individuals with alcohol addiction (OR, 0.40; p=0.0091; 95%CI, 0.22–0.74), by 67% in those with an eating disorder (OR, 0.33; p=0.0074; 95%CI, 0.17–0.65), and by 58% in those who had previously consulted for a mental health problem (OR, 0.42; p=0.0059; 95%CI, 0.22–0.79).

Socio-demographic, clinical and psychopathological predictors of online vs offline gambling addiction.

| Variable | Multivariate logistic regression modela | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 0.93 (0.91,0.96) | <0.001 |

| Place of birth (Spain) | 5.68 (2.27,14.20) | <0.001 |

| Prior consultation for a mental health disorder | 0.42 (0.22,0.79) | 0.007 |

| Alcohol abuse (MULTICAGE CAD-4) | 0.40 (0.22,0.74) | 0.004 |

| Eating disorder (MULTICAGE CAD-4) | 0.33 (0.17,0.65) | 0.001 |

| Excessive Internet use (MULTICAGE CAD-4) | 2.80 (1.42,5.54) | 0.003 |

OR, odds ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

Multivariate logistic regression models to assess independent predictive factors of online vs offline gambling addiction. The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline and the scores derived from the different assessment instruments were included in the model with an entry/stay criterion of 0.20/0.10.

We present an analysis of data collected from people who self-referred to the Adcom center with suspected GD, indicating specific features of this population, as well as identifying independent predictors of online gambling and traditional offline gambling addiction. The data collected also serves to confirm that GD is associated with an elevated presence of other mental disorders. As a result, this analysis helps to broaden our knowledge of the socio-demographic, clinical and psychopathological characteristics (symptoms and mental disorders) associated with GD in the population at large.

Despite growing recognition and professional interest in behavioral addictions, clinical data remain limited. Contributing factors include stigma and patients’ limited insight or inability to recognize their disorder.7 The Adcom center offers individuals in Madrid (Spain) an evaluation of their potential behavioral addictions, voluntary access to a qualified team of professionals with no need for clinical referral, and the possibility of being diagnosed and receiving therapeutic attention. This program aims to increase the number of individuals with addictions that seek assistance before they become overwhelmed with their condition. Additionally, by potentially increasing the number of people diagnosed with behavioral disorders who receive appropriate treatment, this program paves the way to accumulate more clinical and psychopathological data on these conditions.

The large majority of men among those considered to have GD at Adcom was similar to the lifetime prevalence rates of pathological gambling reported elsewhere,30,31 and consistent with data from the Spanish Observatory on Drugs and Addictions (OEDA) on outpatient admissions for behavioral/non-substance addictions across Spain (91.6% men12). There seems to be genetic component associated with GD,32–34 with 1 in 4 individuals with GD reporting a family history of this condition. Whether this genetic component contributes to the sex bias detected remains unclear. However, the higher GD prevalence in men and the greater severity in these individuals allows us to infer a relationship with higher impulsivity in men,16 and perhaps women affected by GD represent a distinct phenotype. Although impulsivity does not constitute a specific diagnostic category, it is an endophenotype that should be diagnosed and treated as such.16

In our cohort, 66.1% had education beyond compulsory secondary school, compared with 9.5% in the OEDA 2023 population.12 Although this difference might reflect a larger proportion of participants younger than 18 years old in that earlier study, there is no difference in the mean age (38 years old) relative to that found here (36.9%). Interestingly, an earlier small sample of Spanish treatment-seeking problem gamblers who only gambled online (n=53) tended to have higher education and socioeconomic status than offline problem gamblers.20 Similarly, the proportion of unemployed individuals with no prior work experience was 2.5% in OEDA and 1.1% in our cohort, suggesting that the inclusion of adolescents in OEDA did not materially influence this estimate. Failure to detect such differences despite the age distributions may reflect specific characteristics of the population with GD across distinct regions in Spain or in the nature of those who would take advantage of a service like Adcom. Therefore, it is possible that strategies such as Adcom increase the number of individuals in the general population with GD that seek help for their problem but specifically, those with specific profiles (e.g., a higher educational level). This merits further study to ensure that such programs adapt to all sectors of the population. Notably, former studies found that help-seeking for GD is less common among male, younger, unmarried, employed problem gamblers or those from an ethnic minority.35

GD frequently coexists with other mental disorders or symptoms (e.g., ADHD, mood disorders, impulse-control disorders and SUDs).8,11,13–15 Hence, GD often goes misdiagnosed and untreated, even within clinical settings.8 Here, GD was most prominently associated with compulsive buying, excessive internet use and alcohol use or disorder. This correlation is consistent with our earlier data from GD patients undertaking specialized treatment.15 Notably, MULTICAGE CAD-4 identified a substantially higher rate of compulsive buying than the qualitative self-report questionnaire, likely because it targets the financial burden and excessive spending associated with gambling rather than discrete purchasing excesses. The proportion of GD patients with ADHD symptomatology (37.4%) was slightly lower than in our previous study (50%),15 yet above the approximately 20% reported elsewhere.36–38 However, as only section A of the ASRS-V1.1 was used to assess ADHD, more precise scales may elevate this figure. There is evidence of a severe psychopathology in GD patients with ADHD symptoms,36,38,39 and a correlation between GD and anxiety or depression.40 The SCL-90-R detected psychopathological distress in 57.4% of participants here, along with depression (64.9%) and anxiety (51.3%). Co-occurrence of SUDs and GD is well recognized,13,41 as is a higher prevalence of SUDs in individuals with GD than in the general population.14,42 As reported in this study, although tobacco and alcohol consumption are the substances most frequently associated with GD,43–46 substance addiction was only identified as a potential problem in 29.1% of participants. These findings confirm what extensive epidemiological studies indicate, that GD is associated with other psychopathological disorders like impulsivity, depression and anxiety. Therefore, the data highlight the importance of diagnosing cases of GD to detect other mental health disorders and implement effective therapies, treating these dual disorders concomitantly.

The recent growth in online gambling highlights the need to identify characteristics specific to online and offline gambling addiction.19,20 In a small clinical cohort, online problem gambling was associated with higher educational attainment, higher socioeconomic status, greater gambling expenditure, and larger gambling-related debt than offline problem gambling. By contrast, clinical, psychopathologic and personality characteristics did not differ.20 Moreover, online gamblers seem to be 10 times more likely to have GD than those who don’t gamble online.31,47 However, offline or online gambling addiction was ascertained in a similar proportion in the individuals with GD who attended AdCom.

The multivariate regression models confirmed that the probability of having online GD drops as age increases, which is consistent with a clear tendency for enhanced digital skills at younger ages and their decline as age increases.48 This tendency is reflected in the marketing strategies of online gambling companies targeting this population. Being born in Spain also predicts online gambling addiction, with a higher probability of offline GD in those born outside the country. Although there can be socio-cultural reasons for this distinction, it may also be explained by other factors associating this non-Spanish/immigrant population with offline GD, such as age difference, lower educational level or lower socioeconomic status,20 or more reluctance to seek professional help. Those with GD and an alcohol problem are less likely to develop online rather than offline GD. However, because sports events are frequently broadcast in bars and online sports betting is available in these venues, problematic alcohol use may increase over time in association with online gambling disorder. Indeed, there is evidence of higher rates of alcohol consumption among online gamblers.9 Having an eating disorder also seems to reduce the probability of developing online GD, possibly reflecting the low proportion of women with online GD (5.3%) and the lower prevalence of eating disorders in men. In fact, eating disorders have been detected in 31% of women with GD and in 7% of men.49 The lower likelihood of online (vs offline) gambling disorder among individuals who previously sought mental health care may reflect age-related help-seeking patterns: older adults are more likely to seek professional help for mental health concerns, whereas younger adults are less likely to seek help for either mental health or gambling problems.35 Finally, as we might expect, excessive internet use is associated with a higher probability of online GD. No psychopathological symptoms seem to predict online vs offline gambling addiction, which is consistent with similar psychopathological profiles for both types of gambling addiction described previously.20,50

This study has limitations. First, participants were self-referred help-seekers and may not represent the broader population with gambling disorder. Second, data were obtained through self-report measures, which are subject to recall and response bias. The use of such instruments also limits the ability to compare data with results from studies using other methodologies and instruments. Third, the cross-sectional design precludes drawing causal inferences between gambling disorder and the variables assessed, requiring longitudinal studies to confirm the findings. Finally, the sample is limited to individuals from only 1 region in Spain, such that similar studies in other regions will be needed to gain a full representation of the population with GD.

Despite these limitations, this analysis leverages data acquired at Adcom using validated instruments to define the characteristics of GD in the general population. We believe this pilot initiative is innovative in the field of mental health. Aimed at the general population and through a self-appointment system, it allows people with GD and/or other behavioral addictions better access to specialized mental health services, providing treatment and prevention strategies. Indeed, it is likely that many of the 265 individuals with GD evaluated at Adcom may not otherwise have sought attention for their problem. Therefore, the findings suggest that targeted, more innovative and wide-reaching efforts may be needed to treat more people with GD. Moreover, this center can collect data that will help understand the current status of GD and other behavioral addictions, generating valuable information to design prevention programs and interventions for such addictions.

FundingThe authors wish to thank Fundación Patología Dual for their financial support to carry out this study. Dr C. Arango received support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), and co-funding from the European Union, ERDF Funds from the European Commission, “A way of making Europe”, financed by the European Union Next Generation EU (PMP21/00051), PI19/01024.PI22/01824, CIBERSAM, Madrid Regional Government (B2017/BMD-3740 AGES-CM-2), European Union Structural Funds, European Union Seventh Framework Program, European Union H2020 Program under the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking: Project PRISM-2 (Grant agreement No. 101034377), Project AIMS-2-TRIALS (Grant agreement No. 777394), Horizon Europe, the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 1U01MH124639-01 (Project ProNET) and Award Number 5P50MH115846-03 (project FEP-CAUSAL), Fundación Familia Alonso and Fundación Alicia Koplowitz.

Conflicts of interestMR declared to have received honoraria/expenses from Takeda and Lundbeck. NS declared to have received honoraria/expenses from Viatris, Recordati, Lundbeck and Otsuka, and research funding from Recordati, Gedeon Richter, Lundbeck and Exeltis. IB has been involved in collaborative activities with Lundbeck, Janssen, Idorsia, and Casen Recordati, and is a shareholder of EMEIS. PV has been involved in collaborative activities with Lundbeck, Camurus, Gilead and Exeltis, and is a shareholder of EMEIS. CA has been a consultant to, or has received honoraria or grants from, Abbot, Acadia, Ambrosetti, Angelini, Biogen, BMS, Boehringer, Carnot, Gedeon Richter, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Medscape, Menarini, Minerva, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sage, Servier, Shire, Schering Plough, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Sunovion, Takeda and Teva. The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

None declared.

As indicated, the AdCom program focuses on a range of behavioral addictions in addition to gambling addiction and among the population attended in the period indicated (n=837), the other behavioral addictions motivating their self-referral were: sex (24.1%); compulsive buying (16.3%); video games (12.2%); and excessive internet use (8.3%).