Individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar disorder (BD) frequently exhibit a disagreement between self-reported and objectively measured cognitive performance. Research suggests that these cognitive discrepancies may vary across disorders and are not exclusive to a specific diagnosis, potentially being influenced by clinical and sociodemographic factors. Overestimating cognitive abilities is associated with better psychosocial functioning in depression, whereas heightened sensitivity to cognitive deficits correlates with worse functioning. However, these phenomena remain underexplored in both depression and bipolar disorder.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study of 200 participants, including 160 patients in full or partial clinical remission (94 with MDD and 66 with BD) and 40 healthy controls. Sociodemographic, clinical, and functional variables were collected, along with both subjective and objective cognitive measures. We conducted a multivariate binary logistic regression to identify factors associated with cognitive discrepancy patterns (under- vs overestimation). Finally, a two-way ANOVA tested the interaction between diagnosis and cognitive discrepancy patterns on psychosocial functioning.

ResultsPatients with MDD tend to underestimate their cognitive abilities, while bipolar patients often overestimate theirs. Patients with higher depressive symptoms (B=−.045, p=.040) and higher intellectual level (B=−.241, p=<.001) report more subjective cognitive disturbances. Worse psychosocial functioning is not associated with underestimation but rather with the diagnosis itself (F=.63, p=.431), with bipolar disorder patients experiencing the most significant impact on daily functioning.

ConclusionsPersonalized cognitive assessments, integrating both objective and subjective measures, are of paramount importance to avoid generalizations and to accurately evaluate cognitive symptoms in patients with affective disorders.

The cognitive profile of individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar disorder (BD) is marked by a significant disagreement between objective and subjective cognitive performance.1–5 In routine clinical practice, it is commonly observed that patients with bipolar disorder (BD) tend to overestimate their cognitive abilities during manic episodes, in contrast to the cognitive impairments identified through neuropsychological testing. Conversely, during depressive episodes or even in euthymic states, BD patients tend to underestimate their cognitive capacities, a tendency found in individuals with MDD. This lack of correlation between self-perceived cognitive difficulties and objective cognitive performance is a complex phenomenon, also observed in other conditions,6–9 making it worthy of closer examination.

In this context, scientific research has examined the patterns of cognitive discrepancy in patients with affective disorders. Contrary to the prevailing clinical impression,2–10 these patterns are not strictly delineated by diagnostic categories and their specific affective states. In fact, the scientific literature suggests the coexistence of both cognitive discrepancy patterns, over- and underestimation of cognitive abilities, in the 2 affective disorders. These patterns are also influenced by various clinical and individual characteristics of the patients.11–15 Furthermore, few studies have accounted for cognitive discrepancies across specific cognitive domains, potentially complicating the interpretation of the disagreement between objective and subjective measures of cognition.11,14,15

Clinical factors such as depressive and manic symptoms can distort the individual's perceptions of his own cognitive abilities. For example, individuals experiencing higher depressive symptomatology, greater number of depressive episodes and/or a longer history of the illness1,11,13–15 may perceive their cognitive performance as significantly impaired due to negative affective biases,16 even when objective measures suggest otherwise. Surprisingly, individuals experiencing manic or hypomanic states may also exhibit an underestimation of their cognitive performance,2,14 even though BD patients usually feel more self-confident during manic or hypomanic states. Individual characteristics such as an older age and a higher verbal estimated intelligence quotient (IQ), can contribute to discrepancies between subjective and objective cognitive measures, potentially indicating an overestimation of cognitive difficulties in both disorders.1,13,14

Another critical question on the disagreement between subjective cognitive perceptions and objective cognitive performance is how this discrepancy can impact on the individual's daily functioning.17,18 In a recent study, Zhu et al. (2024) attempted to elucidate the relationship between sensitivity to cognitive difficulties and health outcomes among patients with depression. The findings indicate that patients with MDD who overestimate their cognitive performance exhibit less functional impairment vs those who underestimate it. Conversely, heightened sensitivity to cognitive deficits is associated with more frequent cognitive complaints, greater discomfort, decreased adaptability, and reduced coping efficacy, collectively leading to poorer psychosocial functioning among MDD patients who underestimated their cognitive competences. However, the impact on daily functioning of cognitive disagreement in patients with bipolar disorder remains unexplored in the current cognitive discrepancy literature. This gap hinders the generalization of findings from depression studies to bipolar disorder, raising the question of whether the true impact on psychosocial adaptation is potentially attributable to the pattern of cognitive discrepancies or is inherently linked to the diagnostic category per se.

Understanding the determinants of cognitive discrepancy in MDD and BD and the relationship between cognitive discrepancy and psychosocial functioning is essential to move forward in the management and treatment of individuals with affective disorders, leading to better long-term outcomes for patients. Hence, the specific aims of the present study are: (i) to explore the existence of different patterns of discrepancy between objective and subjective measures of cognitive functioning in patients with MDD and BD; (ii) to study whether the pattern of cognitive discrepancy is overarching or specific to certain cognitive domains; (iii) to identify sociodemographic and clinical factors that are independently associated with the likelihood of underestimation one's cognitive abilities; and (iv) to examine the interaction effect of diagnosis by cognitive discrepancy pattern (under- or overestimation) on psychosocial functioning. Therefore, both patterns of cognitive discrepancy will be observed in MDD and BD diagnoses. However, underestimation of cognitive performance is expected to be more prevalent among patients with MDD, whereas those with bipolar disorder are likely to overestimate their cognitive abilities. This pattern of underestimation, regardless of the diagnosis of affective disorder, will tend to be associated with poorer functional outcomes.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a multicenter, cross-sectional, case-control study with a 4:1 ratio using a nonprobabilistic sample. The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised 2013). All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the ethics committees of the participating sites (IIBSP-COG-2017-01). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

SampleWe recruited a sample of 200 participants, including 160 patients and 40 HC. Patients were diagnosed as MDD (n=94) or BD (n=66) based on DSM-5 criteria in the outpatient care facilities of each participating center: Hospital Universitari Parc Taulí (Sabadell, Spain) and Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona, Spain). Inclusion criteria were: (i) patients aged 18–60 years, (ii) patients in full or partial clinical remission after a depressive episode, defined by a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17) score≤1419,20 and (iii) the most recent episode being depressive in individuals with BD. The exclusion criteria were: (i) estimated IQ≤85; (ii) presence of current significant comorbid medical conditions, including inflammatory or neurological diseases requiring medication; (iii) past medical history of substance abuse or dependence; (iv) other major mental disorders; (v) current manic symptoms in patients with BD (scores>8 in the Young Mania Rating Scale; YMRS)21; and (v) having undergone electroconvulsive therapy in the previous year. All patients were on their usual treatment with their respective physicians or psychotherapists. HC were recruited from the same geographical areas of the participating centers. Subjects with current or past presence of any psychiatric disorder or having a first-degree relative with major psychiatric disorders were deemed ineligible to participate in the study. The HC group has met the exclusion criteria applied to the patient group.

ProceduresSociodemographic, clinical and functional assessmentA series of different sociodemographic, clinical and functional variables were systematically collected through a clinical interview. Sociodemographic variables included: age, sex, years of schooling and estimated IQ (Vocabulary subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Version-IV, WAIS-IV).22 Clinical variables assessed were diagnosis (MDD or BD), age at diagnosis, number of depressive episodes and hospital admissions, prior suicide attempts, depressive symptoms evaluated using the HDRS-17 and current psychopharmacological treatment. Comorbid psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and/or personality disorders were collected from health records as well. Current psychopharmacological treatment was categorized into 4 groups: non-medicated, antidepressants only, antidepressants plus benzodiazepines, combined treatment (including mood stabilizers and antipsychotics). The Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST)23,24 was used to assess the patients’ psychosocial functioning, with higher scores indicating poorer psychosocial functioning.

Subjective cognitive measuresA trained neuropsychologist administered the Perceived Deficit Questionnaire-Depression (PDQ-D)25,26 or the Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment (COBRA)27 to MDD and BD patients, respectively. The PDQ-D is a self-reported measure of cognitive functioning for use in MDD consisting of 3 subscales, which identify the specific cognitive domains of attention, memory (retrospective plus prospective memory) and planning. The total score ranges from 0 to 80, with a higher score indicating greater perceived cognitive impairment. The COBRA is a 16-item self-report measure that assesses different cognitive complaints common in BD patients.17,18 Specifically, this scale assesses attention and processing speed, verbal learning and memory, and working memory and executive functions. The total score ranges from 0 to 48, with a higher score indicating greater perceived cognitive impairment. In this case, it was specifically developed for BD.

Objective cognitive measuresThe same neuropsychologists assessed the cognitive performance of patients and HC using a neuropsychological battery, including tests that resemble the same cognitive domains of the subjective cognitive measures: the Digits Forward Subtest (WAIS-IV) and the Trail Making Test part A (TMT-A)28,29 to measure attention; the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT)30 to measure verbal memory; the TMT part B (TMT-B),28,29 the number of completed categories of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST),31 and the Phonemic Verbal Fluency Test (PMR Test, adapted for Spanish speaking population)32,33 to measure executive functioning.

Data analysisRegarding the subjective cognitive assessment, the subjective cognitive domains encompassing attention, verbal memory, and executive function were extracted from the PDQ-D scale for the HC and the individuals diagnosed with MDD. The same procedure was conducted using with the COBRA scale in patients diagnosed with BD. Afterwards, the cognitive domains derived from the PDQ-D and COBRA scales, as well as their respective total scores were standardized into z-scores. An aggregate measure, the overall Subjective Cognitive Index, was created by combining the z scores of the PDQ-D and COBRA total scores. To enhance interpretability, both the Subjective Cognitive Index and the individual subjective cognitive domains were inverted, such that higher scores indicated fewer subjective complaints and, therefore, a more favorable self-assessment of cognitive functioning.

In the context of objective cognitive assessment, 3 different cognitive domains including attention, verbal memory, and executive function were defined, along with a general Objective Cognitive Index. For clearer interpretation of participants’ cognitive performance, scores on the TMT-A and TMT-B were inverted to align with the convention that higher scores indicate better performance, thereby ensuring consistency with the other objective cognitive variables. Similarly to the subjective measures, all objective cognitive variables, including the Objective Cognitive Index and its domains were z-transformed transformed using standardized normative population data.

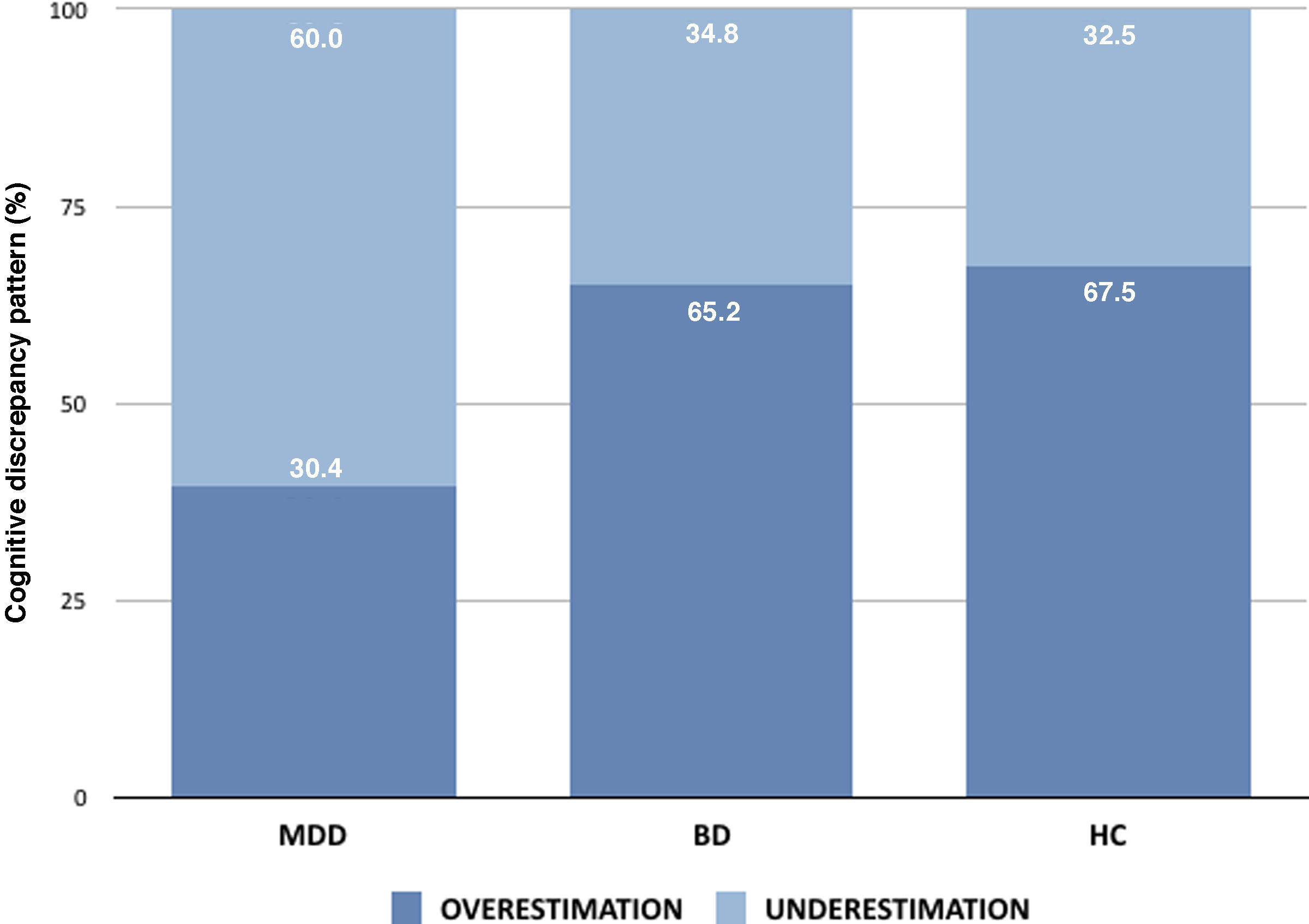

A Cognitive Discrepancy measure was obtained by subtracting the z-score of the Subjective Cognitive Index from the Objective Cognitive Index. Negative values showed an underestimation of cognitive performance, and positive values an overestimation. This method was equally applied to delimit the discrepancy between subjective and objective cognitive domains, yielding discrepancy measures for attention, verbal memory, and executive function. Furthermore, a Cognitive Discrepancy Pattern variable was defined by dividing the Cognitive Discrepancy measure into 2 categories: under- and overestimation. Scores<0 indicate underestimation and scores>0 account for overestimation. A subsequent analysis involved computing the proportion of patients exhibiting under- or overestimation patterns of cognitive performance in MDD and BD patients.

We conducted a descriptive analysis of sociodemographic, clinical, functional, and cognitive measures among groups (HC, MDD, and BD) using parametric tests for quantitative variables or non-parametric for qualitative or non-normally distributed variables. Moreover, we conducted a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis to identify variables independently associated with the Cognitive Discrepancy Pattern as a binary dependent variable (under- vs overestimation). Only the sociodemographic and clinical variables that were statistically significant at an alpha level of 0.10 between under- and overestimation were included in the logistic regression analysis. Finally, to test the last hypothesis of the study a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the interaction effect of diagnosis (MDD or BD) and Cognitive Discrepancy Pattern (under- and overestimation) on psychosocial functioning (FAST total score). The IBM statistical program SPSS version 29 (IBM, Corp. Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data processing and statistical analysis.

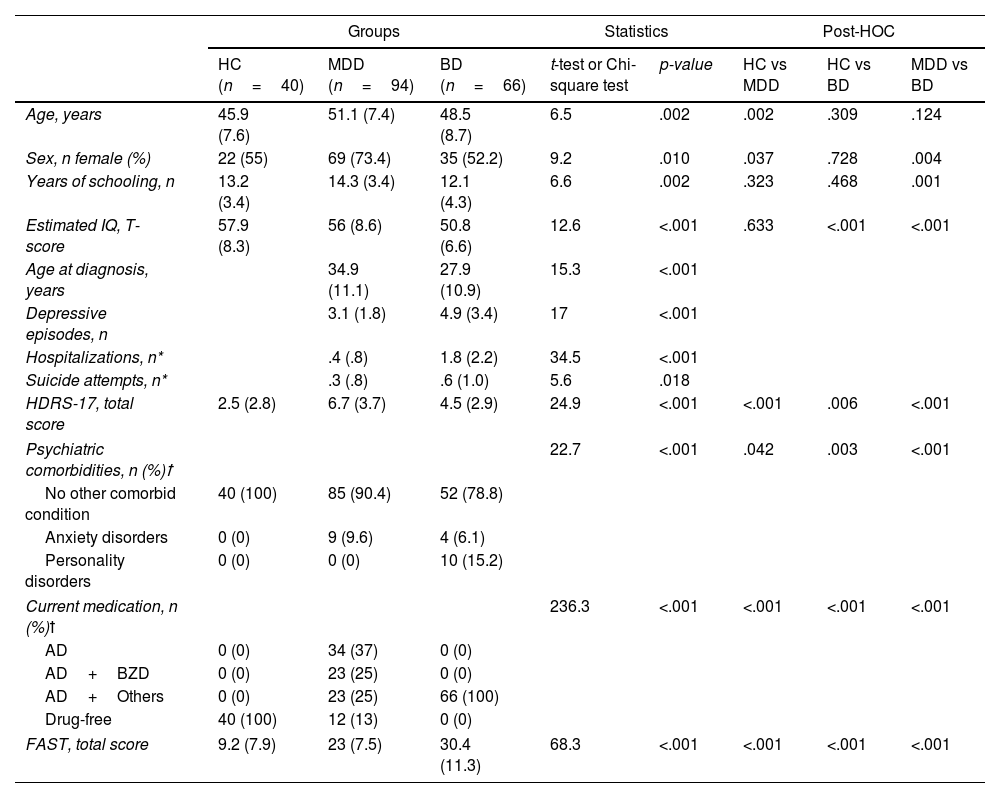

ResultsBaseline comparisons of sociodemographic, clinical, functional and cognitive variablesSignificant differences were observed in sociodemographic, clinical, and functional variables among the 3 groups (Table 1). Patients had a significant worse functioning vs HC (p<0.001), and BD patients had the highest FAST scores although both clinical groups showed moderate-to-severe impairment.

Mean scores (standard deviation) for sociodemographic, clinical and functional characteristics across groups.

| Groups | Statistics | Post-HOC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC (n=40) | MDD (n=94) | BD (n=66) | t-test or Chi-square test | p-value | HC vs MDD | HC vs BD | MDD vs BD | |

| Age, years | 45.9 (7.6) | 51.1 (7.4) | 48.5 (8.7) | 6.5 | .002 | .002 | .309 | .124 |

| Sex, n female (%) | 22 (55) | 69 (73.4) | 35 (52.2) | 9.2 | .010 | .037 | .728 | .004 |

| Years of schooling, n | 13.2 (3.4) | 14.3 (3.4) | 12.1 (4.3) | 6.6 | .002 | .323 | .468 | .001 |

| Estimated IQ, T-score | 57.9 (8.3) | 56 (8.6) | 50.8 (6.6) | 12.6 | <.001 | .633 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Age at diagnosis, years | 34.9 (11.1) | 27.9 (10.9) | 15.3 | <.001 | ||||

| Depressive episodes, n | 3.1 (1.8) | 4.9 (3.4) | 17 | <.001 | ||||

| Hospitalizations, n* | .4 (.8) | 1.8 (2.2) | 34.5 | <.001 | ||||

| Suicide attempts, n* | .3 (.8) | .6 (1.0) | 5.6 | .018 | ||||

| HDRS-17, total score | 2.5 (2.8) | 6.7 (3.7) | 4.5 (2.9) | 24.9 | <.001 | <.001 | .006 | <.001 |

| Psychiatric comorbidities, n (%)ꝉ | 22.7 | <.001 | .042 | .003 | <.001 | |||

| No other comorbid condition | 40 (100) | 85 (90.4) | 52 (78.8) | |||||

| Anxiety disorders | 0 (0) | 9 (9.6) | 4 (6.1) | |||||

| Personality disorders | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (15.2) | |||||

| Current medication, n (%)ꝉ | 236.3 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| AD | 0 (0) | 34 (37) | 0 (0) | |||||

| AD+BZD | 0 (0) | 23 (25) | 0 (0) | |||||

| AD+Others | 0 (0) | 23 (25) | 66 (100) | |||||

| Drug-free | 40 (100) | 12 (13) | 0 (0) | |||||

| FAST, total score | 9.2 (7.9) | 23 (7.5) | 30.4 (11.3) | 68.3 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

HC, healthy controls, MDD, major depressive disorder, BD, bipolar disorder, IQ, intelligence quotient, HDRS-17, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; AD, antidepressants; BZD, benzodiazepines; Others, antipsychotics; lithium or anticonvulsants; FAST, Functioning Assessment Short Test.

Statistic K–W (*) was used when the quantitative variable was not normally distributed and the Chi-square test statistic (ꝉ) was substituted by Linear-by-Linear association test when frequency cell count was <5.

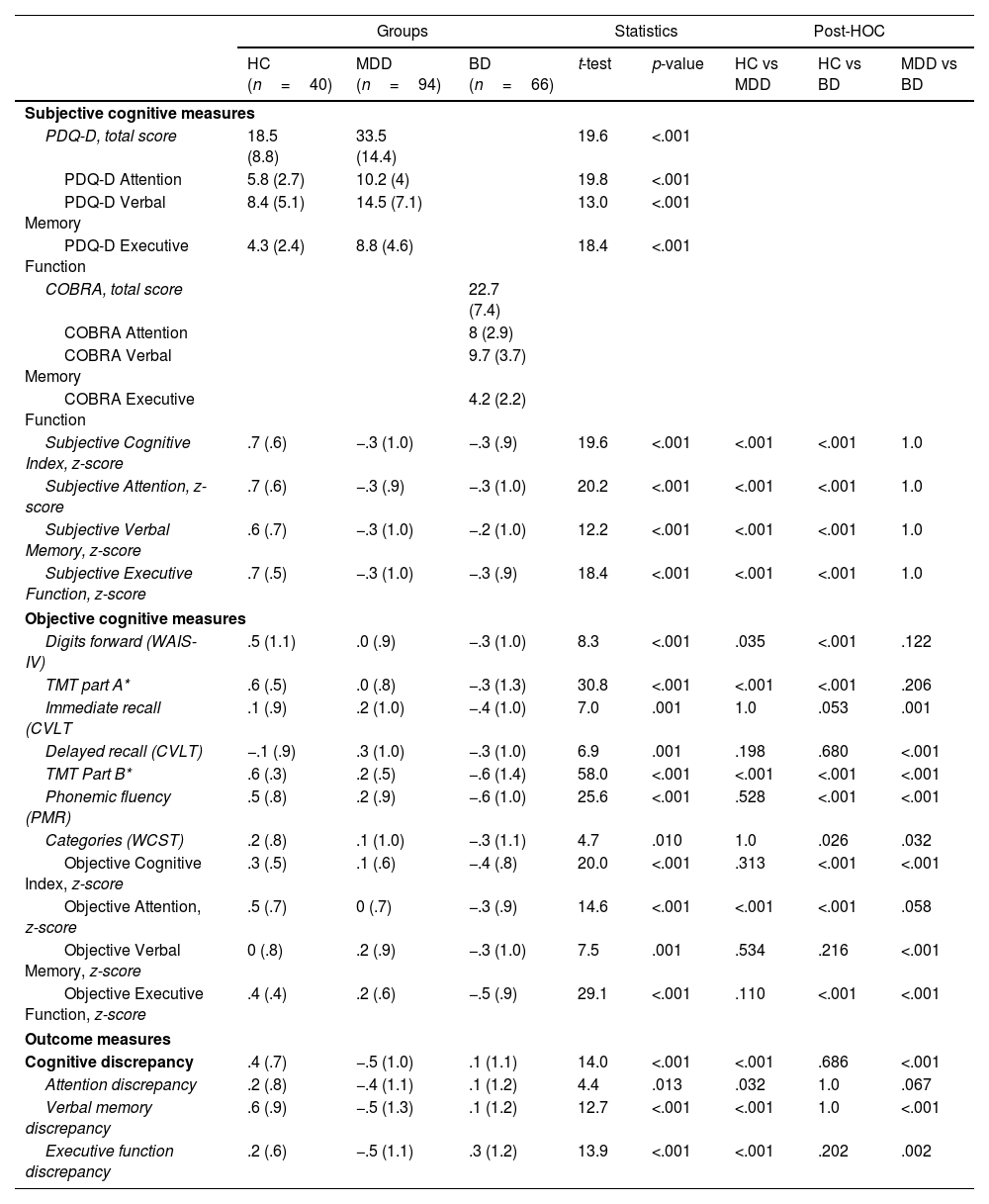

Regarding cognitive variables (Table 2), significant differences were found in the Subjective Cognitive Index, with patients perceiving greater impairment than HC. Although no significant differences in subjective cognition were observed between MDD and BD patients, the latter performed worse than the former on most neuropsychological tests (except in Digits Forward). As expected, BD patients scored the lowest in the Objective Cognitive Index, Objective Verbal Memory, as well as in the Executive Function (non-significant difference in the Objective Attention). Table 2 illustrates the discrepancy variables among the 3 groups, with MDD patients significantly underestimating their cognitive abilities and BD patients overestimating theirs. This pattern of discrepancy persisted across cognitive domains. In detail, significant differences between MDD and BD patients were observed in Cognitive Discrepancy measure, Verbal Memory Discrepancy and Executive Function Discrepancy (non-significant difference in the Attention Discrepancy).

Mean scores (standard deviation) for cognitive characteristics across groups.

| Groups | Statistics | Post-HOC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC (n=40) | MDD (n=94) | BD (n=66) | t-test | p-value | HC vs MDD | HC vs BD | MDD vs BD | |

| Subjective cognitive measures | ||||||||

| PDQ-D, total score | 18.5 (8.8) | 33.5 (14.4) | 19.6 | <.001 | ||||

| PDQ-D Attention | 5.8 (2.7) | 10.2 (4) | 19.8 | <.001 | ||||

| PDQ-D Verbal Memory | 8.4 (5.1) | 14.5 (7.1) | 13.0 | <.001 | ||||

| PDQ-D Executive Function | 4.3 (2.4) | 8.8 (4.6) | 18.4 | <.001 | ||||

| COBRA, total score | 22.7 (7.4) | |||||||

| COBRA Attention | 8 (2.9) | |||||||

| COBRA Verbal Memory | 9.7 (3.7) | |||||||

| COBRA Executive Function | 4.2 (2.2) | |||||||

| Subjective Cognitive Index, z-score | .7 (.6) | −.3 (1.0) | −.3 (.9) | 19.6 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 1.0 |

| Subjective Attention, z-score | .7 (.6) | −.3 (.9) | −.3 (1.0) | 20.2 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 1.0 |

| Subjective Verbal Memory, z-score | .6 (.7) | −.3 (1.0) | −.2 (1.0) | 12.2 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 1.0 |

| Subjective Executive Function, z-score | .7 (.5) | −.3 (1.0) | −.3 (.9) | 18.4 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 1.0 |

| Objective cognitive measures | ||||||||

| Digits forward (WAIS-IV) | .5 (1.1) | .0 (.9) | −.3 (1.0) | 8.3 | <.001 | .035 | <.001 | .122 |

| TMT part A* | .6 (.5) | .0 (.8) | −.3 (1.3) | 30.8 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .206 |

| Immediate recall (CVLT | .1 (.9) | .2 (1.0) | −.4 (1.0) | 7.0 | .001 | 1.0 | .053 | .001 |

| Delayed recall (CVLT) | −.1 (.9) | .3 (1.0) | −.3 (1.0) | 6.9 | .001 | .198 | .680 | <.001 |

| TMT Part B* | .6 (.3) | .2 (.5) | −.6 (1.4) | 58.0 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Phonemic fluency (PMR) | .5 (.8) | .2 (.9) | −.6 (1.0) | 25.6 | <.001 | .528 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Categories (WCST) | .2 (.8) | .1 (1.0) | −.3 (1.1) | 4.7 | .010 | 1.0 | .026 | .032 |

| Objective Cognitive Index, z-score | .3 (.5) | .1 (.6) | −.4 (.8) | 20.0 | <.001 | .313 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Objective Attention, z-score | .5 (.7) | 0 (.7) | −.3 (.9) | 14.6 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .058 |

| Objective Verbal Memory, z-score | 0 (.8) | .2 (.9) | −.3 (1.0) | 7.5 | .001 | .534 | .216 | <.001 |

| Objective Executive Function, z-score | .4 (.4) | .2 (.6) | −.5 (.9) | 29.1 | <.001 | .110 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Outcome measures | ||||||||

| Cognitive discrepancy | .4 (.7) | −.5 (1.0) | .1 (1.1) | 14.0 | <.001 | <.001 | .686 | <.001 |

| Attention discrepancy | .2 (.8) | −.4 (1.1) | .1 (1.2) | 4.4 | .013 | .032 | 1.0 | .067 |

| Verbal memory discrepancy | .6 (.9) | −.5 (1.3) | .1 (1.2) | 12.7 | <.001 | <.001 | 1.0 | <.001 |

| Executive function discrepancy | .2 (.6) | −.5 (1.1) | .3 (1.2) | 13.9 | <.001 | <.001 | .202 | .002 |

HC, healthy controls; MDD, major depressive disorder; BD, bipolar disorder; PDQ-D, Perceived Deficit Questionnaire-Depression; COBRA, Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment; WAIS-IV, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; TMT, Trail Making Test; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

All values are in z-scores, except PDQ-D and COBRA measures that are in raw scores. Statistic K–W (*) was used when the quantitative variable was not normally distributed.

Approximately 60.6% of MDD patients demonstrated a tendency to underestimate their cognitive abilities, while 39.4% overestimated their cognitive performance. Conversely, among BD patients, 34.8% exhibited underestimation of their cognitive capacities, and 65.2% overestimated their abilities (67.5%, overestimation; 32.5%, underestimation in HC; Fig. 1). Significant differences between the under- or overestimation pattern were observed in diagnosis (Pearson Chi-square test, 10.761, p=.001, years of schooling (F=3.047, p=.083), estimated IQ (F=3.057, p=.082), HDRS-17 (F=15.675, p=<.001), and current drugs being used (Linear-by-linear Association=3.265, p=.071), and were eventually included in the regression analysis. The results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that only 2 variables, estimated IQ and HDRS-17, were significantly and independently associated with the likelihood of underestimating cognitive abilities (Hosmer–Lemeshow test: χ2(8)=6.298, p=.614; Nagelkerke's R2=.170). A higher estimated IQ was associated with a Cognitive Discrepancy pattern of underestimation (B=−.045, Wald χ2=4.2, p=.040, OR, .956, 95%CI, .916–.998). Similarly, higher depressive symptomatology was also related to an underestimation pattern (B=−.214, Wald χ2=15.8, p=<.001, OR, .807, 95%CI, .726–.897). Diagnosis, years of schooling, and current medication were not retained in the logistic regression analysis.

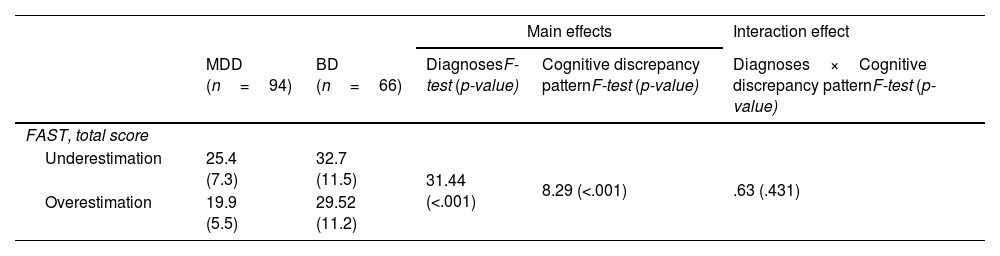

The interaction effect of diagnosis by cognitive discrepancy pattern on psychosocial functioningResults indicated that there was a significant main effect of diagnosis on psychosocial functioning (F=31.44, p=<.001). Although both MDD and BD patients showed moderate impairments in psychosocial functioning, those with BD showed significantly higher scores on the FAST. There was also a significant main effect of cognitive discrepancy pattern (F=8.29, p=<.001), where patients who underestimated their cognitive abilities showed significantly higher scores on the FAST. The interaction effect between diagnosis and cognitive discrepancy pattern was not statistically significant (F=.63, p=.431), indicating that the effect of cognitive discrepancy on psychosocial functioning did not differ between MDD and BD diagnosis. Therefore, although both diagnosis and cognitive discrepancy pattern independently influenced psychosocial functioning, there was no evidence of an interaction effect between these variables. Table 3 included a summary of the two-way ANOVA results on the effects of diagnosis and cognitive discrepancy pattern in FAST scores.

Differences in Psychosocial Functioning (FAST) between diagnosis (MDD or BD) and cognitive discrepancy pattern (under- or overestimation).

| Main effects | Interaction effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDD (n=94) | BD (n=66) | DiagnosesF-test (p-value) | Cognitive discrepancy patternF-test (p-value) | Diagnoses×Cognitive discrepancy patternF-test (p-value) | |

| FAST, total score | |||||

| Underestimation | 25.4 (7.3) | 32.7 (11.5) | 31.44 (<.001) | 8.29 (<.001) | .63 (.431) |

| Overestimation | 19.9 (5.5) | 29.52 (11.2) | |||

MDD, major depressive disorder; BD, bipolar disorder; FAST, Functioning Assessment Short Test.

The present study clarifies the discrepancy between objective and subjective cognition, reinforcing the notion that both patterns of cognitive discrepancy are evident in the 2 studied affective disorders in partial clinical remission. However, a higher proportion of MDD patients tend to underestimate their cognitive abilities, while a greater number of BD patients are prone to overestimate their cognitive performance. Similar patterns of cognitive discrepancy are observed across various cognitive domains. This observation suggests that such discrepancies are not diagnosis-dependent. Instead, depressive symptomatology and intellectual level appear to be the factors associated with the pattern of cognitive discrepancy. Specifically, those patients with higher depressive symptoms and higher intellectual level tend to self-report more subjective cognitive disturbances. Contrary to expectations, poorer psychosocial functioning was not associated with a cognitive discrepancy pattern of underestimation. Instead, it was linked solely to the diagnosis itself, with patients with bipolar disorder (BD) experiencing the greatest impairment in daily functioning.

Among BD patients, 65% reported intact cognitive performance, which is inconsistent with their objective cognitive performance. This overestimation of cognitive abilities, documented in scientific literature as a common trait of BD,2 may be related to the overestimation of abilities typical of manic episodes or to a greater difficulty in recognizing cognitive symptoms associated with the affective disorder. However, a similar phenomenon has been observed in MDD patients in our sample. Nearly 40% of depressed patients tend to overestimate their cognitive abilities, challenging the common belief that depressed patients always report cognitive complaints. This phenomenon of overestimation in affective disorders has significant clinical implications, as these patients could present cognitive symptoms that remain unaddressed due to the absence of self-reported cognitive complaints. Such findings are consistent with other studies suggesting a similar prevalence of overestimation of cognitive performance in both MDD and BD patients.13,14 Consequently, relying solely on self-reported cognitive complaints from patients with affective disorders can result in undetected and untreated cognitive difficulties, thereby hindering their full recovery from the depressive episode.

A total of 61% of MDD patients and 35% of BD patients underestimated their cognitive performance, likely due to residual depressive symptoms and higher intellectual functioning. Depressive symptoms including sadness, pessimism and hopelessness, initiate a cascade of unpleasant thoughts and worries characterized by negative biases. These biases show as a tendency to selectively perceive, interpret, and recall information that reinforces a depressing perspective, while minimizing pleasant stimuli. At the same time, rumination emerges as a maladaptive coping strategy dwell on their symptoms, causes and implications, fostering further distress. This cognitive perseveration not only amplifies negative biases, but also exacerbates feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness. This phenomenon could contribute to a distorted self-perception of cognitive impairment, regardless of patient's objective cognitive performance. Another factor associated with this cognitive discrepancy pattern of underestimation is their IQ level, which serves as a measure of general intelligence, reflecting higher-order cognitive abilities as reasoning and abstraction. One plausible explanation for this finding is that individuals with a higher IQ and a potentially greater capacity for insight and metacognition together with these cognitive biases and rumination inherent in depressive symptomatology heighten up their self-awareness of cognitive performance developing into an underestimation pattern. Understanding these dynamics is essential to develop targeted treatments aimed at disrupting these loops and promoting better management of the associated distress.

Subjective cognitive complaints are closely associated with psychosocial functioning, with individuals reporting greater cognitive complaints often exhibiting poorer functional outcomes.34 In the present study, affective disorder patients with cognitive underestimation showed lower psychosocial functioning vs those who overestimated their abilities. BD patients demonstrated greater functional impairment than MDD patients did, which is consistent with prior research, which is attributable to the episodic nature and severity of mood fluctuations, including depressive and manic episodes. However, the interaction between bipolar diagnosis and cognitive underestimation did not exacerbate functional impairment, suggesting that the diagnosis itself primarily drives psychosocial dysfunction. Other factors, such as objective and subjective cognitive performance, are likely to have a more direct relationship with functioning.34 However, the discrepancy between those 2 cognitive variables does not seem to contribute to the functional impairment. Additionally, bipolar disorder's mood swings, marked by impulsivity and unstable behaviors, contribute to disrupted daily life, strained relationships, and occupational instability, resulting in worse psychosocial functioning compared to major depression.

The extent to which cognitive discrepancy should be considered in our routine clinical practice is still under discussion. Some studies indicate that knowing the degree and direction of cognitive discrepancy will facilitate therapeutic decisions and, therefore, functional improvement in patients with affective disorders.35 However, the present study indicates that when patients under- or overestimate their cognitive abilities, the degree of functional impairment remains predominantly influenced by the underlying psychiatric condition. Therefore, differential diagnosis must also be considered because patients with MDD and those with BD exhibit different cognitive and functional patterns, despite sharing depressive episodes. Instead of focusing on cognitive discrepancy, it may be more beneficial to aim at improving the core symptoms of the disorder, such as directly improving objective cognitive functions and/or promoting a better management of thoughts about one's own cognitive performance. This perspective underscores the importance of avoiding generalizations in affective disorders by emphasizing the key need to assess and evaluate the cognitive symptoms of each individual.

The present study has limitations that should be taken into consideration. Its cross-sectional design allowed for analyzing associations between variables but did not enable tracking cognitive functioning over time or establishing causality. Longitudinal studies are needed to clarify how objective and subjective cognition, and their relationship, impact clinical and functional outcomes in affective disorders. Another limitation relates to the assessment methods. Cognitive self-reports, based on everyday tasks, differ from structured neuropsychological tests conducted in controlled settings, which minimize distractions, enhance motivation, and reduce rumination. Additionally, factors such as residual manic symptoms could also play a role to the cognitive discrepancy observed in BD patients. However, due to the clinical characteristics of the sample, these factors were not analyzed in the regression models. Nonetheless, the bipolar disorder patients exhibited no significant manic symptoms, with a mean of 1.18 (SD, 2.14) in the YMRS. Additionally, bipolar subtype may influence results. However, the limited sample size and imbalance between groups (46 with BD type I and 20 with BD type II) prevented full analysis of this factor. BD type I may lead to greater overestimation of cognitive abilities vs BD type II. Furthermore, Polarity, reflecting the predominance of depressive or manic/hypomanic states was not analyzed. Lastly, this study did not quantify the magnitude of cognitive discrepancy or its impact. Larger, longitudinal studies with better control of confounding factors are essential to understand the relationship between affective disorders and cognitive functioning.

In conclusion, the findings suggest that personalized assessments of cognitive performance, incorporating both objective and subjective measure, are crucial for patients with affective disorders. This comprehensive approach will enable the identification of individuals who may benefit from interventions designed to enhance cognitive functioning, such as cognitive remediation programs or procognitive pharmacological treatments, as well as strategies to improve thought management and alleviate distress through psychotherapy.

Authors’ contributionsMVG: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, project administration, writing original draft, visualization.

MSB, GNV: data curation, investigation, writing review & editing.

JT: formal analysis, writing review & editing.

JDA, DP, CA, JP: resources, writing review & editing.

MJP, NC: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, writing review & editing.

FundingThis study was financed by the Spanish Ministry of Health Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI17/00056, Principal Investigator: Maria J. Portella and PI15/0147, Principal Investigator: Narcís Cardoner) and supported by Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental annual budget of G21 and Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca of the Generalitat de Catalunya (2021SGR00832).

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Data availabilityThe datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

None declared.

We gratefully acknowledge the patients who participated in this study and extend our appreciation to the staff of the Department of Psychiatry at Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau and Hospital Universitari Parc Taulí.