The new coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which emerged at the end of 2019 in the Chinese city of Wuhan, was declared as a pandemic by the World Health Organization on 11 March 2020.

In the most affected countries and regions, in parallel to the high number of patients and the consequent saturation of the health services, the unusually high number of deaths adds a very sensitive burden to authorities regarding the management of corpses.

The purpose of this article is to identify the particular challenges of an appropriate management and coordination of the institutions involved and to propose recommendations for action for the proper and dignified management of the deceased and the protection of the rights of their families to a respectful treatment, to know the fate and whereabouts of their loved ones and to honor them according to their beliefs and customs. The important role that medical-legal services may play for this is highlighted.

La enfermedad por el nuevo coronavirus (COVID-19), surgida a fínales de 2019 en la ciudad china de Wuhan, fue declarada como pandemia por la Organización Mundial de la Salud el 11 de marzo de 2020.

En los países y regiones más afectadas, paralelamente al elevado número de pacientes y saturación de los servicios de salud, la cantidad inhabitual de fallecidos supone un importante esfuerzo de gestión para las autoridades.

El presente artículo tiene como objetivo identificar los retos particulares de una adecuada gestión y coordinación de las instituciones implicadas y proponer recomendaciones de actuación para el manejo correcto y digno de los fallecidos y la protección del derecho de sus familiares a un trato respetuoso, a conocer la suerte y paradero de sus seres queridos y a honrarlos de acuerdo con sus creencias. Se destaca el importante papel que los servicios medicolegales deben jugar para ello.

COVID-19 is a disease caused by the new SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. It is classified for biosecurity purposes as a pathogen which belongs to the same risk group as the causal agents of AIDS-HIV and tuberculosis1.

SARS-CoV-2 is highly contagious and in some infected individuals, especially those who are elderly, it may cause a severe acute respiratory syndrome.

From January 2020, when the International Public Health Emergency (IPHE) was declared, and January 2021, almost one hundred million people have been infected in the pandemic and it has caused the death of approximately a million people worldwide.

The authors of this papers observed that the national action plans in case of catastrophe available in the majority of countries often exclude specific aspects of managing cadavers, and those that do so are designed for scenarios with a high number of deaths in a single event or simultaneous events (natural disasters, technological accidents, armed conflict or terrorist attacks …).

The chief aims of proper management of cadavers in such situations is to identify them and established the cause and circumstances of death. The whole process is the responsibility of the official forensic department, through the intervention of the judicial authority, given that the deaths a violent and either accidental or deliberate cause.

In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, as this cause of death is natural it therefore does not usually require any medical or legal intervention. Forensic departments have therefore mainly not been involved in cadaver management, as this activity has been undertaken by the health authorities. The latter lack the necessary experience in this field, especially when there are a high number of deaths, and their efforts centre on combating the virus and preventing it from spreading.

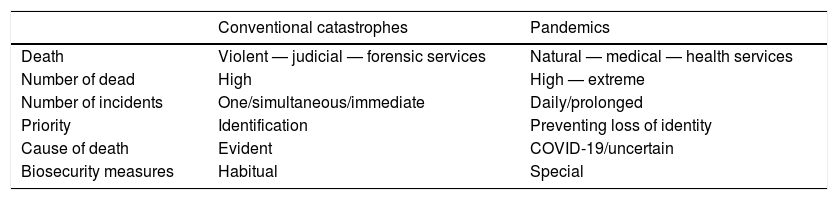

The differences between managing cadavers in conventional catastrophes and pandemic situations are shown in Table 1.

Elements which differentiate conventional catastrophes from pandemics.

| Conventional catastrophes | Pandemics | |

|---|---|---|

| Death | Violent — judicial — forensic services | Natural — medical — health services |

| Number of dead | High | High — extreme |

| Number of incidents | One/simultaneous/immediate | Daily/prolonged |

| Priority | Identification | Preventing loss of identity |

| Cause of death | Evident | COVID-19/uncertain |

| Biosecurity measures | Habitual | Special |

Two principle aspects have been identified in connection with managing the cadavers of individuals who died due to COVID-19:

- 1.

Biomedical measures which have to be applied by those who handle or contact with the cadavers of individuals who have died because of or with the suspicion of having died due to COVID-19 infection, to prevent the transmission of the disease.

- 2.

Management of a large number of deaths over a prolonged period of time, which overwhelms normal cadaver management systems, especially certification systems, including the identity of the person who has died and the cause of death (the health system), the registration of deaths, transport and deposit (civil registry and undertakers) and the final resting place (cemetery personnel).

The majority of countries have public health laws and laws governing emergencies which develop the general constitutional principles which attribute the protection and care of citizens in case of catastrophe to the State.

The norms which are usually linked to cadaver management include civil law on the registration of deaths and the issue of death certificates (Registry Office) and the Public Health Funereal Authorities (cadaver transport, thanatopraxis operations, burials and cremations), as well as penal law on the practice of judicial autopsies.

The management of cadavers of individuals who died due to COVID-19 has to fit the type of state organisation (centralised or federal, etc.) and the legal framework of each country. In some cases this will require the modification of certain regulations or the preparation of additional specific norms, guidelines or directives. This will facilitate the work necessary to respond properly and suitably to the high number of deaths caused by the pandemic2–5.

The procedure for the “Prevention and control of infections for the safe management of cadavers in the context of COVID-19”, published on 24 March 2020 by the WHO3, contains a series of provisional guidelines for undertakers and health centres, religious and public health authorities, families and everyone concerned in managing the cadavers of individuals who have died due to COVID-19, either confirmed or presumed. It also includes certain observations that are of interest for the proper management of cadavers, such as: a) the need to avoid any haste in managing the dead, with the recommendation that the authorities should work on a case-by-case basis, taking the rights of the family into account, together with the need to investigate the cause of death and to prevent exposure to infection; b) the need to respect and protect the dignity of the dead and their cultural and religious traditions at all times, as well as their families, and c) the false belief that it is necessary to cremate those who have died due to a transmissible disease.

Biomedical aspects of cadaver managementAs well as the known protocols and international guides on procedures for cadaver management in disaster situations6–8, in recent months medical and forensic organisations and institutions have prepared technical documents on the cadaver management procedures in cases of COVID-19. These documents give instructions on how they should be transported to the morgue, conditions under which autopsy may be performed, transport to the mortuary and final destination, all adapted to how the pandemic has evolved9–22.

Although to date there is no scientific evidence for the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 due to handling the cadavers of individuals who died of COVID-19, this is thought to give rise to a low risk of infection for the individuals who enter into direct contact with them (medical and forensic personnel, undertaker and cemetery staff). Certain measures should therefore be implemented in the transport of cadavers, such as personal hygiene measures and the use of appropriate personal protective equipment, containing bodily fluids, taking bodies to the morgue as soon as possible, reducing movement and manipulation to a minimum, and taking specific measures for cleanliness and environmental control during autopsy23 if one is necessary, and during burial.

Although scientific studies have proven that coronaviruses are able to persist on inanimate surfaces such as metal, glass or plastic for a few days, they can easily be deactivated using common disinfectants24. The personal effects and other objects in the homes of those who have died should not therefore represent any risk after these measures have been implemented.

Clinical autopsies were not considered to be advisable at least at the start of the pandemic in confirmed cases of COVID-19. Nevertheless, partial autopsies with biopsies being taken from the main organs were recommended, based on the biological hazard of contagion and propagation of the virus through aerosols and splashes during the autopsy procedure25.

However, in cases of violent death, with special emphasis on cases of homicide, deaths in custody or suspects with COVID-19, forensic services have to intervene to offer answers to judicial authorities on the cause and circumstances of death when they request this, while always complying with the recommended biosecurity and protection protocols.

It is therefore necessary for the relevant authorities to provide the required measures and create protocols for action, supplying their workers with the essential biosecurity equipment and resources to guarantee their protection. This would include the availability of sufficient items of personal protective equipment (PPE) and supplying indispensable training for its correct use; disinfectant material and biological residue elimination devices, together with a sufficient amount of body bags and coffins.

The lack of the necessary material: a) raises ethical questions about the priority for action by the personnel who deal with the sick, as opposed to those who deal with the dead and who enter into contact with cadavers or their fluids; b) limiting manipulation of cadavers and therefore the reliability of diagnoses on the cause of death, and c) increasing the risk of exposure to the virus and the possibility of spreading it.

Aspects associated with cadaver managementThe immediate result of cadaver management systems being overwhelmed is that they would accumulate in hospitals and homes, with the consequent reaction by families and public opinion, which would demand that the authorities implement effective measures. However, as we know from other situations involving conventional catastrophes, the absence of specific plans leads to the adoption of improvised measures, with the risks that this involves:

- •

A lack of respect in how the dead are treated, when bodies are stored in undignified conditions, or when mass cremations take place or burial in common graves.

- •

When cadavers cannot be traced, due to a lack of proper labelling or the loss of labels or other identifying elements during the process of deposit and transport, resulting in the loss of their identity (administrative disappearance).

- •

The possibility that cases of death judicial interest which should be studied forensically will not enter the judicial process (false negatives). Deaths under conditions of loss of liberty should receive special attention (in police stations, prisons, psychiatric hospitals or social care centres), as the State may share responsibilities in these cases.

- •

Lack of leadership, unsuitable coordination of the institutions involved (the Ministries of Health and the Interior, Civil Protection, Defence, Justice…), when there is no clear lack of cooperation, which may sometimes arise due to political rivalries between different levels of the administration (local, regional, national…).

- •

Fragmentation and dispersion of information among the institutions involved (names, hospital registries, documentation, lists of transfers and transports, locations within cemeteries …), which restricts the possibility of communication or the transmission of complete, true and transparent data to family members and public opinion, generating a lack of trust in the management process.

- •

Deficient treatment of family members, if they are hindered from accessing information through the usual channels, aggravated by the limited mobility imposed by the authorities; prohibitions against the practice of funeral rites and a lack of psychosocial support networks.

All of the above considerations would therefore involve the violation of the rights of the dead and their families to be treated with dignity and respect, and of the right of family members to know the fate and final destination of their loved ones who have died26,27.

There is therefore a clear need to develop specific plans for action in situations of pandemic.

Responsibility for the response. Action planA chaotic response in cadaver management is often the result of a lack of specific contingency plans and a clear assignation of responsibilities. We often see that action is fragmented and uncoordinated.

A holistic response based on a single plan and under the leadership of a single coordinating institution should include the following general guidelines28:

- •

It has to include the different institutions that are involved and the procedures which they have to follow, ensuring the necessary cooperation and a sufficient flow of information to all operative levels, to maintain cadaver traceability at all times.

- •

Flexibility so that it can adapt to new needs as they arise.

- •

Appropriate training and information for the personnel who implement the adopted procedures to undertake the tasks they are assigned.

- •

A guarantee of the safety and well-being of working personnel, including biosecurity measures and the necessary psychological support.

- •

Provide the necessary consumables and ensure that they are available (PPE, body bags, coffins, temporary morgues, information systems …), establishing contact with the bodies and/or companies which supply them.

- •

Have sufficient personnel, which may require an increase in the number of workers or the restructuring of their shifts and/or functions (such as reassigning personnel who perform tasks which are not essential) for the duration of the crisis.

- •

Ensure that the dead and their families are treated considerately and with dignity, including the supply of information, emotional support and respect for their cultural traditions.

- •

Adopt the measures which are necessary to guarantee the identification of cadavers in the future when this has not been possible prior to their burial.

The main requisites of the procedure:

- 1.

Designation of a single institution (to be decided based on the context of working) which will coordinate all of the other parties involved, with full authority and responsibility for cadaver management.

- 2.

Establishment of a single operations centre, which centralises information and coordinated decision-making:

- o

Designation of the individuals in charge of each one of the stages in cadaver management. Each one of them will be in charge of generating a two-way chain of transmission to the operative workers in the procedures undertaken by each one of the institutions involved, and the incidents which may arise.

- o

Operative assignation of the personnel in the institutions to the different functions performed, in a dynamic way which depends on the availability of resources and the needs deriving from the evolution of the pandemic. Nevertheless, the responsibility for the management of each phase and coordination of the participating institutions will still be determined by the original design.

- o

- 3.

Implementation of a single system of labelling for cadavers and the means used to transport them (body bags, coffins …) which ensures correct traceability and the chain of custody throughout the process.

- 4.

Management of a centralised information system that is controlled by the institution in charge of coordination, which is used to share all of the information obtained by each one of the institutions involved in cadaver management from place of death to their final resting place, according to the above scheme. This element is considered fundamental for:

- o

Coordinated decision-making as processes evolve.

- o

Control of cadaver traceability.

- o

Information available in real time for transmission to the authorities, the families of the deceased and public opinion.

- o

- 5.

Installation of temporary morgues, depending on needs. Rather than mere storage centres, these must be understood to be places for the processing, collection and recording of the data corresponding to each one of the people who have died, completing the administrative steps and verifying their identity if necessary before they are finally laid to rest. Each one of these centres would have a manager (evaluate the institution in charge) with a general coordinator for all of the centres (located in the operations centre). The said centres must have cooling systems to preserve cadavers (such as refrigerated containers) while guaranteeing the security, privacy and dignified treatment of the deceased.

- 6.

Ensure an orderly process for transport from temporary morgues to cemeteries once the necessary steps have been completed. The frequency of departures should depend on the capacity of the cemeteries to place cadavers in their destinations, avoiding the dispatch of large numbers of bodies and guaranteeing a rigorous chain of custody and traceability.

- 7.

Do not cremate any cadavers that are not identified or not claimed.

- 8.

Establish a psychosocial support system:

- o

For family members:

- •

Develop a platform for the supply of information. This could be implemented using data transmission media and the social networks, etc., during the time in which the mobility of the population is restricted, and then face-to-face once such restrictions are lifted.

- •

Psychological and emotional support, preferentially by including local institutions and organisations (the local health service, NGOs and other agents working in the area of mental health), working in coordination under a shared action plan.

- o

For the personnel who are involved in cadaver management: through the above-mentioned channels.

- o

Medical centres are usually unable to respond to ensure the appropriate management of an excessively high number of deceased patients, and in certain contexts it is not rare for cadavers to be stored in different places without a due process of labelling or without the necessary security measures to prevent the possibility of manipulation and breakage of the bags and labels.

The actions of health services in the appropriate management of cadavers should be designed to:

- •

Prepare reliable procedures for the registration of hospitalised patients and the labelling of cadavers, thereby contributing to the necessary traceability of patients who have died in medical centres.

- •

Facilitate certification by the doctors involved in care of the individuals who die, in the cases where this is of no judicial interest (natural causes without signs of violence or any suspicion of criminality)29,30.

- •

Give forensic services access to the clinical histories of patients, when a cadaver enters the judicial circuit.

- •

Facilitate the practice of microbiological analyses for judicial cadavers. This helps to control risk in cases which will be subjected to a judicial autopsy, while also permitting the detection of positive cases which would otherwise not have been counted.

As well as the role which they usually play in cases of violent death or when there are suspicions of criminality (custody of the body and investigation of the facts), the security forces have the material and human resources which allow them to help in the response to the pandemic, especially through the transmission of information to the forensic services on the circumstances of death, together with any background or information supplied by family members in cases of deaths at home or unidentified cadavers.

UndertakersThese are in charge of transporting cadavers to temporary morgues and preparing them for the mourning ceremony (e.g., a wake) and final destination, according to the wishes of the family of the deceased, as well as to manage the transport and repatriation of cadavers.

Registry officesThe excess number of death certifications will require the adoption of measures such as the use of data transmission to receive and send documents (death certificates and burial licences) while also increasing opening hours.

CemeteriesPlanning for a high number of arrivals of cadavers because of a pandemic necessitates the adoption of contingency measures that make it possible to increase the frequency of burials and cremations.

This may require the urgent preparation or construction of additional areas for burials, including specific areas for unidentified cadavers.

In extreme cases when it is necessary to consider the option of trench burials (which are in principle not advisable), trench digging and the arrangement of the bodies should follow international recommendations7.

The capacity of crematoria may also be limited by the admission of a large number of bodies. Due to this and with the aim of responding to an increase in the number of cremations requested by family members, the possibility of transporting bodies should be considered (e.g., between provinces). This would require the corresponding biosecurity arrangements, taking into account the fact that bodies, once the bag has been disinfected and the coffin containing it has been sealed, does not represent any risk of transmission.

Social servicesThe authorities must take charge of adopting the necessary measures for appropriate psychosocial support for family members and the personnel involved in cadaver management. This should be adapted to their cultural needs, and preferentially supplied by local sources of support (university departments in the area of mental health and/or psychology, professional associations, NGOs …)31.

Forensic servicesForensic services have to perform the valuable work of collaborating with public health services when multiple deaths occur during a pandemic. Their advice and support for medical authorities may be essential for the preparation of action protocols for the management of large numbers of cadavers caused by the pandemic, obtaining a diagnosis in cases of judicial interest and suspicion of infection that would otherwise go undiagnosed.

As occurs under normal circumstances, cases of death reach the forensic circuit when they have no apparent cause or recent symptoms of infection by COVID-19, as well as violent deaths or those with the suspicion of criminality or unidentified bodies. Given that a large proportion of carriers are asymptomatic or only have mild symptoms, it is possible that their bodies will carry the virus. It is therefore important to take into account the recommendations issued by the scientific community32–36.

The problematic situation which arises when individuals with restricted freedom or unidentified individuals, especially migrants, die should be mentioned expressly.

Deaths under conditions of restricted freedom. The pandemic led to a large part of the worldwide population being locked-down or in quarantine. This was especially significant for those individuals who were already confined, as their rights were restricted and they are exposed to a higher health risk because of the prolonged confinement they experience.

Under these circumstances it is essential to prevent the entrance of the virus into prisons and other places of confinement, to prevent or minimise the appearance of infections and severe outbreaks.

It is therefore essential to prepare contingency plans to guarantee an appropriate medical response and to keep places of detention safe.

International Humanitarian Law and International Human Rights Law make it obligatory to investigate cases of death in individuals who are confined, even when the cause is apparently natural and did not arise in the place of confinement but rather, for example, in a hospital to which they had been taken. A proper investigation that includes a judicial autopsy is a guarantee for society that authority is being exercised correctly, and that no such death is the result of maltreatment, torture or a lack of correct care37.

A procedure for conjoint action by penitentiary, medical and forensic institutions should be designed to plan for a considerable increase in COVID-19 infections in centres of confinement, with the resulting deaths among the interned population, according to legal demands and the applicable international standards37–39.

Unidentified cadavers. A forensic identification procedure must be prepared for unidentified bodies. This identification procedure must be complete and multidisciplinary, with a single centralised registry to hold identifying information such as cadaveric fingerprints, photographs, X-rays and samples for DNA analysis (although without using invasive techniques), as well as all other data in connection with the cadaver and missing persons, generating a report agreed by the different specialists taking part and coordinated by an expert in identification.

Cremation of the cadaver should not be authorised in these cases, and nor should it be buried in a common grave. Measures must be implemented to ensure the correct traceability of the cadaver, so that it has to scrupulously follow the chain of custody until its final destination.

Hospitals should be instructed using specific training programmes on the procedure for managing and transporting unidentified cadavers to the forensic department, including aspects in connection with dignified and respectful treatment, information for the family, respect for cultural and religious traditions, traceability and the chain of custody for those who have died.

Data managementThe entire plan for action in a situation of catastrophe or public calamity requires a centralised data management system.

Due to the large number of people who die in a short period of time and in different places (cities, provinces…) and in different locations (hospitals, homes and outside), and as different institutions take part in managing this (medical, police, military, undertakers, cemeteries…), the resulting information is usually fragmented and dispersed throughout the process (names, hospital registries, chain of custody documentation, death certificates, lists of transfers and transports, photographs, locations within cemeteries), with a low level of exactitude and reliability, and with limitations in the traceability of cases.

Consolidating all of the information deriving from the actions involved in cadaver management within a single centralised physical file facilitates: a) coordinated decision-making based on the continuous evaluation of processes; b) control of cadaver traceability, and c) real time availability of information for transmission to the authorities, family members of those who have died and the media, thereby adding to credibility and strengthening citizens’ trust in the authorities.

Appropriate management of cadavers necessarily involves time limits that are widely surpassed because of the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic, which may give rise to delays of days or even weeks in the final arrangements for those who have died, as has been seen in severely affected countries.

Access to complete and accurate information allows the authorities to evaluate the efficacy of management, detecting errors and correct actions, so that they will be prepared to respond to the demands and uncertainties of society.

As opposed to policies of mass burial, with the risk of errors that they involve, fluid, true and transparent information supplied to citizens regarding the reasons for delays arising from the need to follow procedures which guarantee proper management of cadavers is essential to protect the rights of those who have died and their families. This will respond in a satisfactory way to the uncertainties of family members regarding the destination of their loved ones who have died.

Governments must therefore develop a public communication strategy.

Conclusions- •

The public disaster due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with thousands of deaths in a short period of time, is an extraordinary challenge within many fields for the proper management of the cadavers that has technical and humanitarian implications, making specific contingency plans necessary.

- •

The said plans must include the dignified and respectful treatment of those who have died and their families. They must also offer measures which facilitate cadaver management, including their recovery and transport, traceability and the chain of custody, effective information management and a system to care for family members and the personnel involved in the management of those who have died.

- •

Proper implementation of action plans requires the designation of a single institution to lead and coordinate decision-making, as well as the collaboration of all the institutions involved.

- •

COVID-19 disease should not lead to the suppression of autopsies in cases which give rise to judicial interest (violent death or the suspicion of criminality). The scope of each autopsy should be adapted to the circumstances of each case, and always with the adoption of the requisite biosecurity measures.

This study did not receive any specific grant from any agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Prieto Carrero JL, Fondebrider L, Salado Puerto M, Tidball Binz M. La gestión de las personas fallecidas a causa de la pandemia de COVID-19 y los retos organizativos desde la óptica de los servicios medicolegales. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2021;47:164–171.