Bipolar disorder is a relapsing-remitting condition affecting approximately 1–2% of the population. Even when the treatments available are effective, relapses are still very frequent. Therefore, the burden and cost associated to every new episode of the disorder have relevant implications in public health. The main objective of this study was to estimate the associated health resource consumption and direct costs of manic episodes in a real world clinical setting, taking into consideration clinical variables.

MethodsBipolar I disorder patients who recently presented an acute manic episode based on DSM-IV criteria were consecutively included. Sociodemographic variables were retrospectively collected and during the 6 following months clinical variables were prospectively assessed (YMRS,HDRS-17,FAST and CGI-BP-M). The health resource consumption and associate cost were estimated based on hospitalization days, pharmacological treatment, emergency department and outpatient consultations.

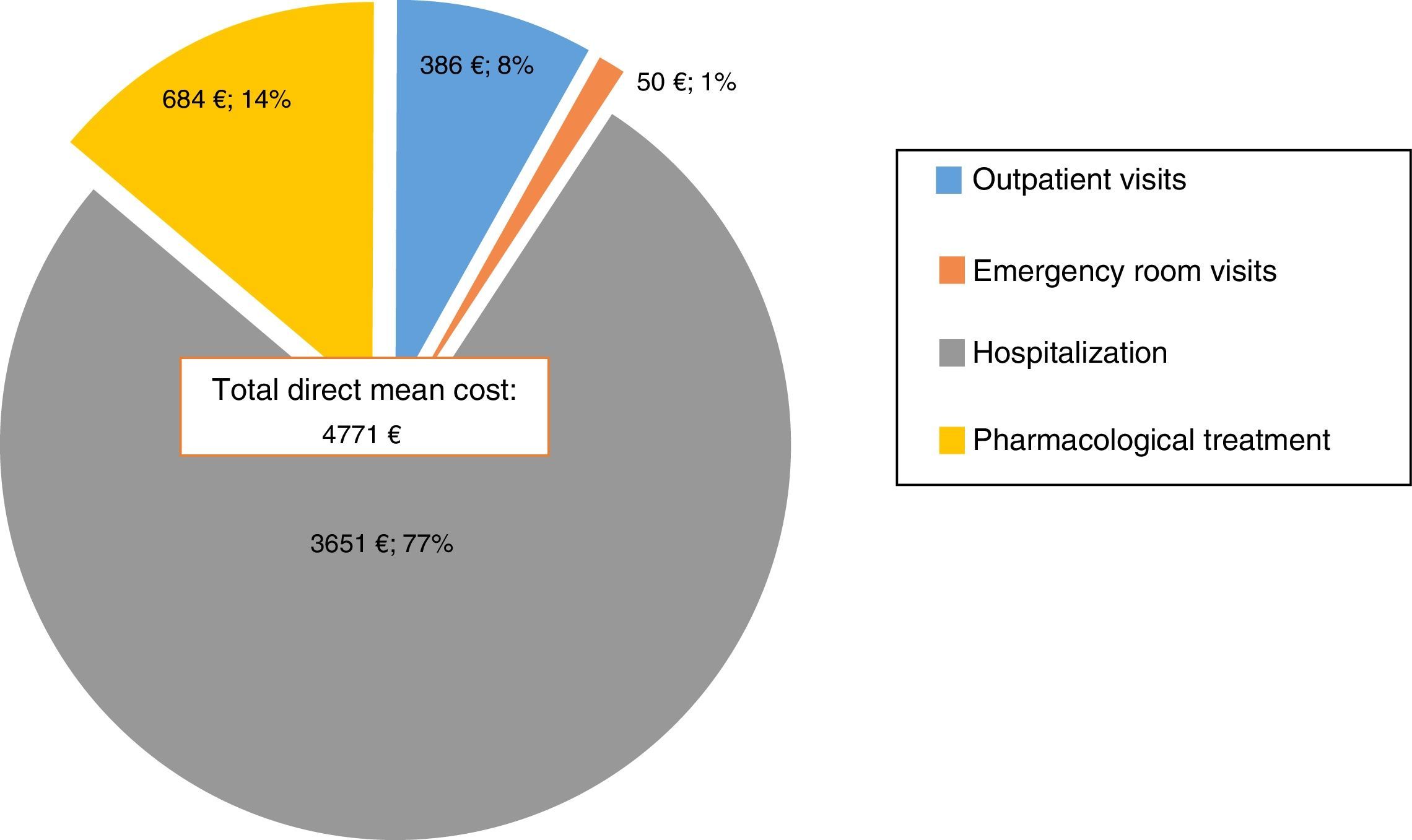

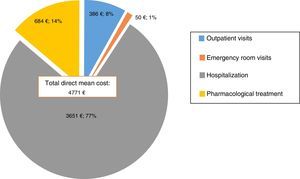

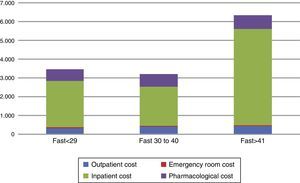

ResultsOne hundred and sixty-nine patients from 4 different university hospitals in Catalonia (Spain) were included. The mean direct cost of the manic episodes was €4771. 77% (€3651) was attributable to hospitalization costs while 14% (€684) was related to pharmacological treatment, 8% (€386) to outpatient visits and only 1% (€50) to emergency room visits. The hospitalization days were the main cost driver. An initial FAST score >41 significantly predicted a higher direct cost.

ConclusionsOur results show the high cost and burden associated with BD and the need to design more cost-efficient strategies in the prevention and management of manic relapses in order to avoid hospital admissions. Poor baseline functioning predicted high costs, indicating the importance of functional assessment in bipolar disorder.

El Trastorno Bipolar (TB) es una enfermedad con frecuentes recaídas y remisiones que afecta a aproximadamente el 1 al 2% de la población mundial. Aún con la eficacia de los tratamientos disponibles actualmente, las recaídas son frecuentes. Por tanto, el costo y consumo de recursos asociados a cada nuevo episodio tienen un impacto importante en el sistema sanitario. El principal objetivo de este estudio fue el de estimar los costos directos y recursos sanitarios empleados durante el tratamiento de episodios maníacos en la práctica clínica diaria, teniendo en cuenta además variables clínicas.

MétodosFueron incluidos de manera consecutiva pacientes quiénes hayan presentado recientemente un episodio maníaco agudo según los criterios del DSM-IV. Se recogieron de manera retrospectiva variables sociodemográficas y durante los siguientes 6 meses se realizaron evaluaciones clínicas sistemáticas que incluían YMRS,HDRS-17,FAST and CGI-BP-M. El consumo de recursos sanitarios y los costos asociados fueron estimados a partir de los días de hospitalización, el tratamiento farmacológico, las visitas a urgencias y ambulatorias.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 169 pacientes de 4 hospitales universitarios de Cataluña, España. El costo directo medio de cada episodio maníaco fue de €4771. De estos, 77% (€3651) correspondía a los costos de hospitalización, 14% (€684) al tratamiento farmacológico, 8% (€386) a las visitas ambulatorias y solo 1% (€50) a visitas en urgencias. Los días de hospitalización fueron el mayor componente del costo total. Un puntaje inicial de FAST >41 predijo de forma significativa un mayor costo directo.

ConclusionesNuestros resultados demuestran el elevado costo y consumo de recursos sanitarios asociados al TB y reflejan la necesidad de diseñar más y mejores estrategias costo-efectivas en el manejo y prevención de episodios maníacos a fin de evitar ingresos hospitalarios. Un peor estado funcional basal es predictivo de mayores costos, indicando la importancia de realizar una evaluación funcional en el TB de manera sistemática.

Bipolar disorder (BD) affects approximately 1–2% of the world population.1,2 It has a high impact on patient's functioning, quality of life and mortality.3,4 BD is the second cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) within mental health disorders and the eighth cause when considering all medical conditions, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).5 This chronic and lifelong disorder consists of recurrent episodes of mania, depression and the symptom overlap of the aforementioned, usually referred to as mixed states, as well as subsyndromal phases between episodes.6,7

Due to the need of more sustainable healthcare programs, there is increasing interest in the economic burden of mental disorders.8 In Europe, the total cost (direct, indirect and non-medical) of mental disorders has been estimated in €461 billion, one-third of which is related to direct health care costs.9 Regarding BD, the total annual cost estimation is €21.4 billion and €111 billion (151 billion USD) in Europe and the United States, respectively. Indirect costs, such as early retirement, unemployment, time off work and productivity lost account for 75–86% of the total cost.10,11 The difference of bipolar disorder associated costs between US and Europe might be more explained by the diverse methodologies utilized among the studies in each region12 rather than previously proposed different disease management patterns (i.e. hospitalization length of stay) and healthcare systems.13

Calculating BD burden from an economic perspective is a complex task, as there are many variables to take into account such as: clinical setting (outpatient vs inpatient), healthcare systems, cost estimate approach, among others, as reported in a recent review by Kleine Budde et al.12

The unique hallmark of BD is mania,14 which is associated with a significant disruption in the individual's social and occupational functioning. Manic recurrences are also associated with high morbi-mortality and healthcare resource consumption.15–18 However, studies addressing the costs associated with manic episodes are scarce, despite the fact that more than 50% of the admissions in BD are due to these kinds of episodes and that hospitalizations represent one of the most important cost drivers.19–23

Real-world clinical information on costs associated with mania will help in the design of cost-effective and tailored-designed treatment strategies for manic patients. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to estimate the health resource consumption and direct costs associated to manic episodes, in a real world clinical setting, taking into consideration clinical variables.

MethodsDesign and participantsThe present study combined prospective and retrospective data collection and analysis. Clinical data were captured prospectively as part of the systematic assessment of the Barcelona Bipolar Disorders Program24 and this model was also adopted by the other hospitals involved in the study.

The Barcelona Bipolar Disorders Program is a specialized multi-disciplinary care program whose main aims are focused on the diagnosis of bipolar disorders through standardized assessments as well as on tailored and evidence-based pharmacological and psychological treatments during a systematic follow-up. Hence, regardless of the unit where the patient is receiving assistance (inpatient or outpatient), a common battery of assessments are routinely carried out and the results are registered by trained specialists.

The naturalistic cohort study sample involved 169 consenting, systematically followed-up, adult patients from four different psychiatric hospitals and outpatient clinics from Catalonia, Spain. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the respective Hospital ethics committee. The selected patients were 18 years or older, with a BD type-I disorder according to DSM-IV-TR25 criteria and already included for at least 6 months in a systematic follow-up bipolar disorder program at their respective Hospitals. The main inclusion criterion was having a manic episode, defined as fulfilling DSM_IV-TR criteria for mania and having a Young Mania Rating Scale26 score of ≥15. This index episode could have been handled in an inpatient or outpatient setting depending on the patient's clinical severity and psychiatrist's criteria. The data were analyzed retrospectively to ensure no sponsor bias in medication choice. Patients were recruited between January 2012 and January 2013.

Procedure and data collectionAttending psychiatrists of inpatient and outpatient clinics were asked to identify and facilitate a list of patients who could meet inclusion criteria during this period of time. Taking these criteria into consideration, each possible case was carefully evaluated before inclusion by a psychiatrist in charge of the study in the involved centers. The explanation and participation in the study were offered after the remission of the acute symptoms to the selected patients. In the case they agreed to participate, an informed consent was requested to access their medical records and register their clinical information.

Socio-demographic information was extracted from the medical records, as well as medical and psychiatric history. Relevant information on the course of the BD was obtained: age, number and type of the first and following episodes, suicide attempts, previous hospitalizations and predominant polarity (defined as based on at least a two-fold excess of one polarity). Together with clinical information about the index episode, employment-functional status, clinical setting (outpatient vs inpatient) and the treatment received were collected. Individual treatments were determined clinically by each patient's psychiatrist, and included lithium, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, antidepressants, benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Further clinical assessments were carried out at one and six month follow-up.

Clinical assessmentsPatients were evaluated at baseline and follow-up through similar standardized clinical assessments, included in the bipolar disorders program protocol of each Hospital. Systematic follow-up consisted of periodic appointments with their psychiatrist and included: a clinical interview and assessment of manic symptoms through the Spanish version of the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS26,27) and depressive symptoms with the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-1728,29). The Spanish version of the CGI-BP (CGI-BP-M30,31) was routinely used to assess the patient's global clinical state. The Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST32) was the measure selected to evaluate psychosocial functionality. Neurocognitive performance of the patients was assessed through the SCIP-S scale,33 at some but not all the study sites, depending on the availability of a neuropsychologist. Treatment adherence was assessed with the Spanish version of the 4-item Morisky-Green test.34,35 To define specific outcomes of the index episode and to better characterize individual illness history, we used operational definitions of symptomatic response (50% improvement in mania symptom severity using YMRS), symptomatic remission (YMRS<8), recovery (remission sustained ≥8 weeks), relapse (new DSM-IV-TR episode of mania within 12 weeks of remission) and recurrence (new manic episode >12 weeks following remission) according to the recently published International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force recommendations.36

Even though the standardized follow-up requires at least one appointment every 3 months for stable patients and every 1 month after a hospital admission, the frequency and number of outpatient appointments as well as the treatments prescribed varied according to the clinical circumstances of each patient. In the same way, the patients were able to request additional outpatient appointments or go to the emergency room at any time they considered necessary.

Cost estimatesWe adopted a bottom-up approach to estimate the costs associated with the manic episodes from a payer perspective. Even though, the centers involved belonged to the Spanish public health care system, the individual services costs were not standardized but did not differ greatly. This is probably because they have a common regional regulatory agency. Therefore, health resource utilization was calculated considering a mean cost for each health service offered (i.e. days of hospitalization, outpatient and emergency department consultations) and the final prices listed at the centers involved. The listed prices included hospital inpatient costs per day, laboratory tests, professional consultations (psychiatrist, psychologist and social worker), but excluded the expenses associated with pharmacological treatment given during the admission. Pharmacological treatment costs were calculated taking into account the 2012 drug retail listed by the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency plus VAT per milligram and multiplying it for the average dose per day received by the patient during the admission and follow-up. Direct total cost was defined as health resource utilization plus pharmacological treatment cost. No inflation rate was added to the calculation, considering the short time between the conduction of the study and analysis of the data (maximum 12 months apart).

Data analysisOnly individuals with at least 2 follow-up assessments were included in the analysis. Statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18.0. A descriptive analysis of socio-demographic and clinical variables was conducted. BD history included age of onset, number and type of episodes and suicide attempts. Baseline score of the assessment scales used was compared to subsequent scores during follow-up with a dependent T-test. Pearson correlations were conducted to initially find possible relationships between resources consumption, direct cost and clinical variables. Subsequently, those variables which showed significant associations were included into the multiple regression analyses and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to explore the relationship between socio-demographic or clinical variables with resource utilization and costs. In order to compare the employment status between the index episode and after six months Chi-square analysis was performed. All the analyses were two-tailed with alpha set at p<0.05.

ResultsSample description169 bipolar I participants were recruited from the four participating centers as follows: 59 from Reus, 40 from Barcelona, 37 from Manresa and 33 from Lleida. Mean age was 42.5 years (SD=12.8), with 46.2% females. Since the vast majority were already followed-up by their respective specialized care programs, all the selected patients agreed to participate in the study and gave their informed consent. Fifteen subjects (8.8%) were lost to follow-up.

Regarding marital status, 70 (41.4%) were single, 63 (37.3%) married, 30 (17.8%) divorced/separated and 6 (3.6%) widowed. Nearly three-quarters of the participants were inpatients (No.=133, 78.7%) at the time of the inclusion while only 36 (21.3%) were outpatients.

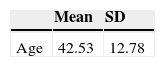

About one quarter of the participants were on permanent sick leave (n=43, 25.7%), 28 (16.8%) were on partial sick leave, 41 (24.6%) unemployed and 11 (6.6%) retired. Only 44 (26.3%) subjects were actively working at the time of inclusion. Other sociodemographic variables of the sample are given in Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample.

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.53 | 12.78 |

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 91 | 53.8 |

| Female | 78 | 46.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 70 | 41.4 |

| Married | 63 | 37.3 |

| Separated/divorced | 30 | 17.8 |

| Widowed | 6 | 3.6 |

| Educational level | ||

| Low | 93 | 55.4 |

| Medium | 31 | 18.4 |

| High | 44 | 26.2 |

| Employment status | ||

| Active | 44 | 26 |

| Unemployed | 41 | 24.6 |

| Partial sick leave | 28 | 16.8 |

| Disability | 43 | 25.7 |

| Retired | 11 | 6.6 |

| Living situation | ||

| With family | 74 | 43.8 |

| With parents | 51 | 30.2 |

| Alone | 29 | 17.2 |

| Others | 15 | 8.9 |

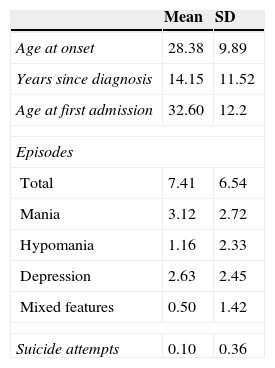

Concerning clinical characteristics, 58.9% of the sample had a family history of psychiatric disorders, with 22.5% BD. Mean years from diagnosis of BD were 14.2 (SD=11.5). Mean onset age was 28 years old (SD=9.8). Manic predominant polarity was more frequent (40.5%) than depressive predominant polarity (23.8%). In 35.5% of the sample, predominant polarity was unspecified. Almost 90% of the patients had at least one hospital admission related to their BD and half of the sample (51.5%) had a comorbid substance use disorder (SUD).

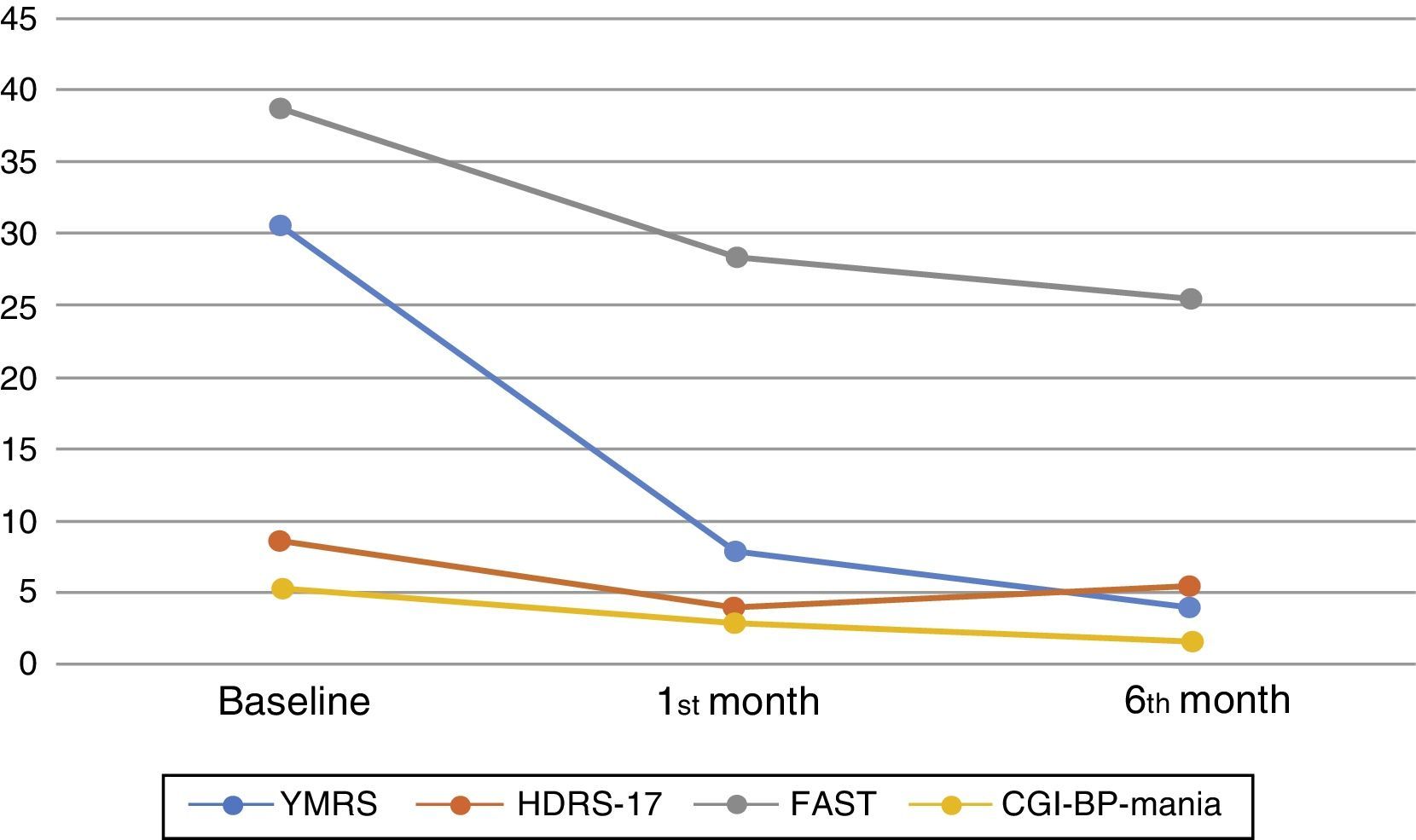

At baseline, the mean YMRS score was 30.6 (SD=9.2), whereas the HDRS-17 mean score was 8.45 (SD=4.7). CGI-BP-M had a mean score of 5 (SD=1.6). Other clinical characteristics are detailed in Table 2.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at onset | 28.38 | 9.89 |

| Years since diagnosis | 14.15 | 11.52 |

| Age at first admission | 32.60 | 12.2 |

| Episodes | ||

| Total | 7.41 | 6.54 |

| Mania | 3.12 | 2.72 |

| Hypomania | 1.16 | 2.33 |

| Depression | 2.63 | 2.45 |

| Mixed features | 0.50 | 1.42 |

| Suicide attempts | 0.10 | 0.36 |

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| SUD co morbidity | 87 | 51.5 |

| Other psychiatric co morbidities | 41 | 24.7 |

| Non-psychiatric comorbidities | 53 | 31.4 |

| Family past psychiatric history | 99 | 58.6 |

| Suicide attempt history | 39 | 23.2 |

| Rapid cycling history | 8 | 4.7 |

SUD: substance use disorder.

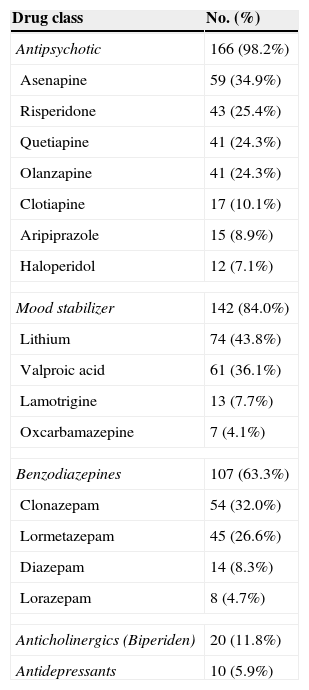

The vast majority of patients (98.2%) were treated initially with antipsychotics including aripiprazole (8.9%), asenapine (34.9%), olanzapine (24.3%), quetiapine (24.3%) and risperidone (25.4%). Most of them were used in combination with mood stabilizers. The most commonly prescribed drug was lithium (43.8%), followed by valproic acid (36.1%). In total, eighty-four percent of the patients received at least one mood stabilizer. Further details about pharmacological treatment are given in Table 3.

Percentage of the most frequent drugs used initially for the manic episode treatment.

| Drug class | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Antipsychotic | 166 (98.2%) |

| Asenapine | 59 (34.9%) |

| Risperidone | 43 (25.4%) |

| Quetiapine | 41 (24.3%) |

| Olanzapine | 41 (24.3%) |

| Clotiapine | 17 (10.1%) |

| Aripiprazole | 15 (8.9%) |

| Haloperidol | 12 (7.1%) |

| Mood stabilizer | 142 (84.0%) |

| Lithium | 74 (43.8%) |

| Valproic acid | 61 (36.1%) |

| Lamotrigine | 13 (7.7%) |

| Oxcarbamazepine | 7 (4.1%) |

| Benzodiazepines | 107 (63.3%) |

| Clonazepam | 54 (32.0%) |

| Lormetazepam | 45 (26.6%) |

| Diazepam | 14 (8.3%) |

| Lorazepam | 8 (4.7%) |

| Anticholinergics (Biperiden) | 20 (11.8%) |

| Antidepressants | 10 (5.9%) |

Three-quarters of the patients were hospitalized during the index episode. In all of them the main reason for admission was the current manic episode itself. Mean hospitalization was 19.8 days (SD=11.6). Only two variables predicted an increase in hospitalization days: having a higher initial YMRS (β=0.419, p<0.001) and having any kind of medical comorbid condition (β=0.166, p<0.05). An average of 3.5 (SD=1.2) drugs were used simultaneously during the index manic episode in both out and inpatients. Using multiple regression analysis with a stepwise method (F(2, 115)=215.307, p<.001, adj R2=0.786), the number of drugs used during follow-up were determined by a higher number of treatments initially prescribed (β=0.862, p<.001) and the presence of a comorbid medical condition (β=0.133, p=0.003). Other non-significant variables included in the model were age, psychotic features and the presence of other comorbid psychiatric conditions. Although patients presenting psychotic symptoms during the index manic episode spent twice as much time as inpatients than those who had no psychotic symptoms (27 vs 14 days respectively, p<0.001), this trend was not statistically significant (β=0.11, p=0.208) when age, psychiatric and medical comorbidities were controlled.

Outpatients needed an average of 1.83 (SD=2) appointments with their psychiatrists within the first month after the index episode and a mean of 4.20 (SD=3.4) appointments during the 5 following months (0.84 visits/month). After discharge, the inpatient group needed more outpatient appointments (7.7, SD=5.2) when compared to the former (T=3.8, p<0.001). Patients with a comorbid SUD needed 1.3 times more visits (T=−2.38, p=0.01). These results remained the same after controlling for potentially confounding variables such as age and other comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions.

Eighty percent of the sample (n=134) needed at least one hospital admission during the study and 9.4% (n=11) had to be readmitted at least once. During the six months following the index episode, the mean number of emergency rooms visits was 7.4 (SD=5.11). Thirteen percent of the sample needed at least one emergency room consultation, although there were no significant differences between groups and no clinical variables were found to be predictive of emergency rooms visits either.

Direct costsThe mean direct cost of the manic episodes was €4771 (SD=6402). 77% (€3651) was attributable to hospitalization costs, while only 14% (€684) was related to pharmacological treatment, 8% (€386) to outpatient visits and only 1%(€50) to emergency room visits (Fig. 1). In other terms, daily costs of treatment per inpatients were €43.47, of which almost €34.57 were attributable to hospitalization costs, whereas outpatients had a daily cost of €16.58 of which €6.85 corresponded to treatment associated costs.

The direct healthcare costs of the patients who required hospitalization during the manic episode were almost 2.5 higher when compared to the outpatient group (T=2.6, [95% CI 760–5510] p<0.01). Number of hospitalization days (β=0.891, t=25.75, p<0.001) was the best predictor of the total direct cost after controlling for the number of medications received (β=0.103, t=2.9, p=0.004) and Emergency room visits (β=0.100, t=2.9, p=0.005) with a multiple regression analysis using an stepwise model (F(3, 151)=228.8, p<.001, adj R2=0.819) which excluded the number of outpatient visits (β=−0.037, t=−1.05, p=0.294).

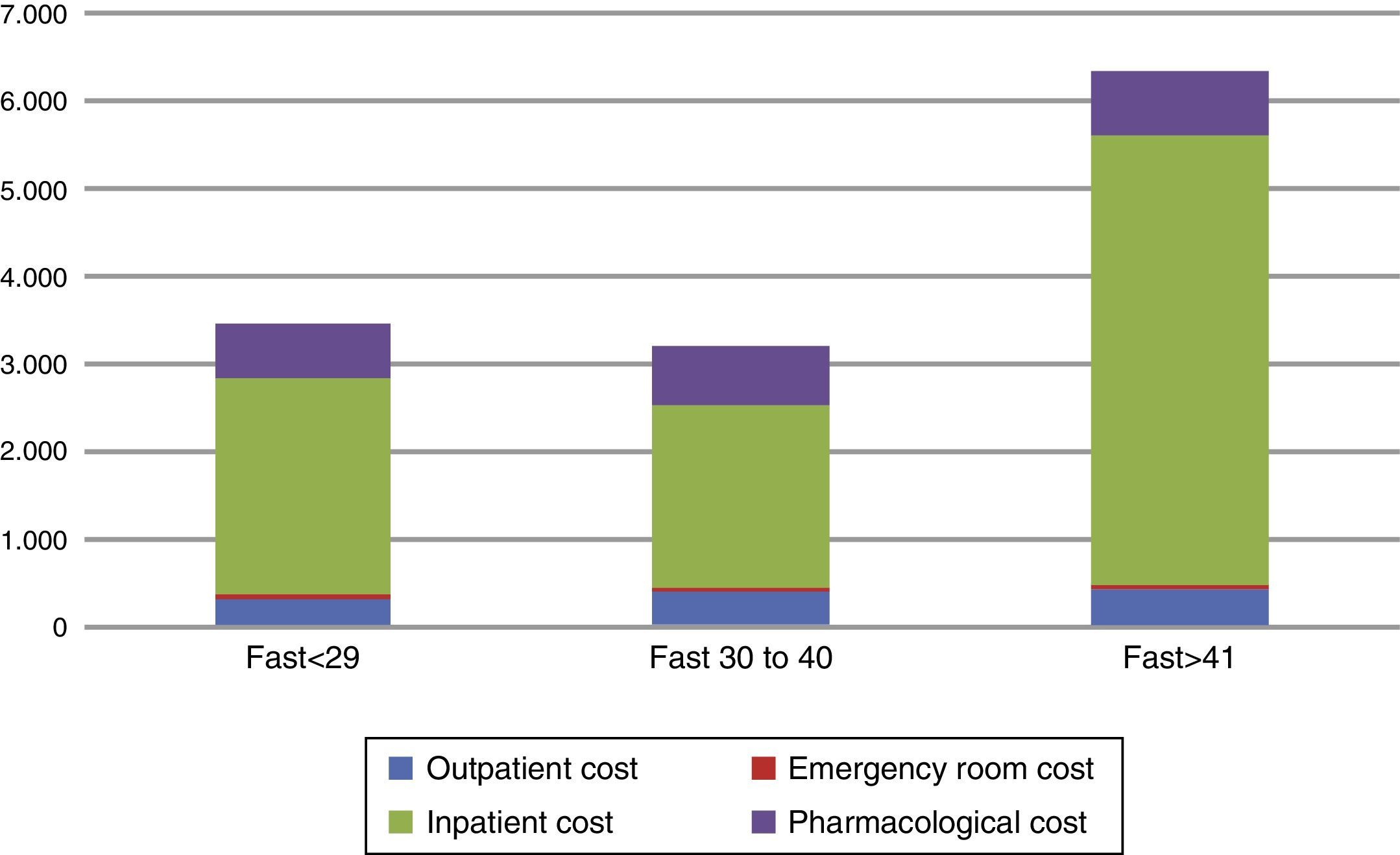

Since the hospitalization cost was clearly the main cost driver, we explored possible clinical variables that could predict the total cost within the subgroup of patients who had been hospitalized at least once during the study period. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) controlling for number of pharmacological treatments received, YMRS score and days of hospitalization showed that those with an initial FAST score >41 had a significant difference of more than €1000 when compared to those with a FAST score <29 (€6418 vs €5123, F(2, 110)=2.166, p<0.05). That is, patients with more functional impairment had a higher economical cost (Fig. 2).

Distribution and total direct healthcare costs between initial FAST score categories. *Cutoff score was based on FAST score percentiles among the total sample. The figure shows the distribution among the direct healthcare cost components associated to the different levels of the baseline FAST score.

FAST: Functional Assessment Short Test.

Adherence to pharmacological treatment prescribed was acceptable during follow-up according to the 4-item Morisky-Green test with almost 60% and 91% of the sample showing high and medium adherence respectively and only a small percentage of patients reported low medication adherence (9%) at the end of the follow-up.

Alcohol consumption was associated with more than a two-fold risk of having low adherence to treatment (OR=2.45 [95%CI=1.5–5.3], p=0.01) in a multivariate logistic regression. Other non-significant variables included in the model were psychotic symptoms, number of previous episodes and rapid cycling.

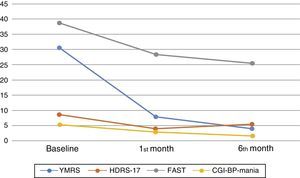

One month after the first assessment, the mean YMRS was reduced by 22.9 points, which is an improvement of almost 75% (T=30.95, p<0.001) whereas the mean HDRS-17 was reduced by 4.4 points (T=11.6, p<0.001). An improvement of more than 50% was observed in the CGI-BP-M, with a mean reduction of 2.6 points in the manic symptoms score (T=27.3, p<0.001). The FAST scale score improved by almost 25% (T=9.6, p<0.001), but only 28.4% (No.=48) had achieved functional remission (FAST≥11). On the other hand, global change in the neurocognitive domains was not significant when considering SCIP scores (T=1.18, p=0.243). These findings remained significant after controlling by potentially confounding variables: age, years since diagnosis and number of past episodes (Fig. 3).

The progression of cognition, psychiatric symptoms, and functionality at baseline and during follow-up. YMRS: Young mania rating scale, HDRS-17: 17 items Hamilton Depression rating scale, FAST: Functional Assessment Short Test, CGI-BP-Mania: Mania subscale of the Modified version of the Clinical Global Impression for Bipolar Disorder. The figure shows the mean results of the assessments carried out at baseline and during the follow-up taking into consideration the whole sample.

During follow-up, symptomatic improvement was maintained, with further score reduction of 3.9 points in the YMRS (T=7.7, p=0.002), 1.35 points in the CGI-BP-M (T=10.7, p<0.001), and a mean reduction of 2.5 points in the FAST (T=3.1, p=0.002). There was a slight increase of 1.13 points in the HDRS-17 (T=−3.23, p<0.001). Neurocognitive performance measured by the SCIP test remained unchanged.

Finally, regarding employment situation, there was a significant percentage of patients returning to active work at the end of the study, with 30% in partial sick leave during the index episode and 10.6% at six months (X2=17.13, p<0.001).

Specific pharmacological treatment approaches and detailed response results exceed the scope of this paper.

DiscussionConsistent to previous studies, this study highlights the high economic burden associated with mania in terms of direct cost and healthcare resource utilization in a naturalistic “real world” setting, the highest cost being related to hospitalization, followed by pharmacological treatment, outpatient visits and emergency room visits.

The estimated total direct healthcare cost of a manic episode is €4771, which is similar to a previously published study.37 Tafalla and colleagues estimated a cost of nearly €4500 using a similar bottom-up approach, of which 56% corresponded to hospitalization expenses, 10% outpatient specialized care, 14% antipsychotics, 15% from other psychoactive drugs and about 3.6% corresponded to primary care associated cost. Our estimations showed that almost 77% of the total amount corresponded to hospitalization-associated costs, while only 14% could be attributed to pharmacological treatment. The small differences between both studies could be explained by several factors, such as the fact that the former was conducted in a single center, with fewer patients and clinical variables were not considered. Another reason could be the health care policies and administrative differences between the regions where each study was conducted.

Despite the different approaches and results among other studies evaluating the direct costs associated with BD, there is consistent data and agreement in identifying hospitalization as one of the most important cost drivers. Hospitalization costs associated with manic episodes ranges from 50% to up to 80% of total direct expenses.19,20,22,23 Furthermore, in our study patients who had been hospitalized needed more outpatient appointments after discharge.

The biggest cohort, used in a study carried out by Gou et al. (2008), involving 67.862 BD patients, reported that 31% of the healthcare costs were due to inpatient expenses, with almost 20% of which were caused by medical or psychiatric comorbidities.38 This is in accordance with our findings, as we observed that both manic symptom severity and comorbid medical conditions were strong predictors of more hospitalization days and higher direct costs.

Another study somewhat similar to our approach was conducted in 2002 by Olié et al. in France.39 The evaluation consisted of the cost associated to manic hospitalized episodes with a follow-up of 3 months during which they found a percentage closer to our results (98%) regarding hospitalization costs, with only insignificant amounts pertained to medication and medical consultations. However, the total direct healthcare cost reported of €22,297 was much higher and different from our results even though their follow-up was 3 months shorter. Again, several differences between both studies can explain these diverse results although probably the best explanation may be that the French study only included hospitalized patients while we also considered outpatient care which had a much lower cost (€2322) compared to the inpatient care (€5457). An additional reason that should be considered when interpreting these findings is the difference between healthcare systems and the longer mean hospital stay (47 days) compared to our results (20 days).

Functionality has been proven to be an important prognostic variable40–42 and in our study only 28.4% achieved a functional remission at 6 months which is consistent with previous studies.42,43 An interesting finding is the potential predictive value of the initial FAST score on the total cost of mania. Even though it is premature to consider the FAST scale as a reliable tool to estimate costs in a manic episode, it is a promissory finding and further studies evaluating this matter are warranted. Having this kind of clinical tools could be of paramount importance to design more cost-effective intervention strategies.

This study has some limitations. One of the first is the fact that the four hospitals involved were reference centers for BD, which may imply a more severe or unstable sample as well as the high percentage of inpatients. This fact could also have contributed to higher costs compared to other general mental healthcare centers due to the more intensive healthcare for this specific group of patients. Secondly, being a multicenter study increases the chance of variations in the clinical management and treatment as well as their respective costs. Thirdly, the resources and services available in each center were diverse which limited the possibility of considering other healthcare associated costs uniformly (i.e. outpatient psychological groups and visits, social work sessions and day hospital admissions, non-psychotropic drugs, general practitioner visits). Part of the clinical data was collected retrospectively. Additionally the periodicity of the assessments and the follow-up time was short, taking into consideration a chronic relapsing disease as BD. These facts could limit the generalizability of the results to other settings.

Despite the previous limitations, there are some advantages of our study that are worth mentioning. The study was conducted in specialized settings with highly trained psychiatrists, and consequently diagnosis and assessments accuracy are almost guaranteed as well as a similar approach regarding treatment during a manic episode. The unit costs were not based on prevalence assumptions but individually. Furthermore, one of the main strengths was the possibility to control the cost components with clinical variables under “real world” naturalistic conditions, conversely to clinical trials in which, for instance, almost half of our sample would have to be excluded due to a comorbid substance-use disorder or medical condition. Finally, the assessment of functional outcomes, which is a critical piece of clinical assessment nowadays,44 is rarely performed in cost-effectiveness studies, and the MANACOR is the first to report a significant association between baseline psychosocial functioning and direct health care cost.

Mainly the diverse and heterogeneous methodologies between different studies about costs in BD comparisons are controversial, difficult and probably inaccurate, especially regarding the total costs. Consequently, the cost variance is substantial among the available ones and that is the main reason why international standardized methods of estimating cost are urgently needed.12 Future initiatives should concentrate their efforts to find these standardized methods in order to adequately generalize results across settings and evaluate cost-effective treatment strategies.45 Meanwhile direct cost calculations can give important information to determine the management of BD in the healthcare systems.

In conclusion, our results are consistent with what other studies had found regarding the high cost and burden associated with BD, yet they also emphasize the need to design more cost-efficient strategies in the prevention and management of relapses in order to avoid hospital admissions since it remains the main cost driver, and they support the use of specific strategies for relapse prevention, such as psychoeducation, and intensive outpatient care. Of particular relevance, and new to the field, the finding that a major predictor of health care cost is baseline functioning measured with the FAST indicates that a careful assessment of functioning and interventions such as functional remediation46 might be particularly helpful to reduce costs associated to mania in the context of BD.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingThis study was funded by Lundbeck supported by an Emili Letang Grant from Hospital Clínic of Barcelona (to H), by a Research Grant from Clínica Alemana, Universidad del Desarrollo de Santiago (to U), by a grant from Beatriu de Pinós, Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement, de la Generalitat de Catalunya i del programa COFUND de les Accions Marie Curie del 7è Programa marc de recerca i desenvolupament tecnològic de la Unió Europea (to R) and by the Instituto Carlos II trough the Centro para la Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM) as well as Grups Consolidats de recerca 2014 SGR 398 (to V).

Conflict of interestProf. V is a consultant or grant recipient with: Almirall, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Elan, Eli Lilly, Ferrer, Forest Research Institute, Gedeon Richter, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Janssen-Cilag, Jazz, Lundbeck, Merck, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Schering-Plough, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and United Biosource Corporations. Dr. U has been a speaker for Janssen-Cilag. Dr. H has received traveling grants from Lundbeck to attend conferences. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank Lorena Moreno, Psy, for her collaboration in this study.

Please cite this article as: Hidalgo-Mazzei D, Undurraga J, Reinares M, Bonnín CdM, Sáez C, Mur M, et al. Los costos y consumo de recursos sanitarios asociados a episodios maníacos en la práctica clínica diaria: el estudio MANACOR. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc).2015;8:55–64.