The aim of this study was to provide a descriptive overview of different psychological and pharmacological interventions used in the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder and substance abuse, in order to determine their efficacy. A review of the current literature was performed using the databases Medline and PsycINFO (2005–2015). A total of 30 experimental studies were grouped according to the type of therapeutic modality described (pharmacological 19; psychological 11). Quetiapine and valproate have demonstrated superiority on psychiatric symptoms and a reduction in alcohol consumption, respectively. Group psychological therapies with education, relapse prevention and family inclusion have also been shown to reduce the symptomatology and prevent alcohol consumption and dropouts. Although there seems to be some recommended interventions, the multicomponent base, the lack of information related to participants during treatment, experimental control or the number of dropouts of these studies suggest that it would be irresponsible to assume that there are well established treatments.

En este trabajo se analiza la utilidad de diferentes intervenciones psicológicas y farmacológicas empleadas en el abordaje de pacientes con trastorno bipolar y abuso de sustancias. Se realizó una búsqueda bibliográfica en las bases de datos Medline y PsycINFO (2005–2015). Un total de 30 estudios experimentales se describen agrupados según el tipo de modalidad terapéutica (farmacológica 19; psicológica 11). La quetiapina y el valproato han demostrado superioridad en la mejora de los síntomas psiquiátricos y en la reducción del consumo de alcohol, respectivamente. Las terapias psicológicas grupales con psicoeducación, prevención de recaídas e inclusión de la familia han resultado favorables para reducir la sintomatología y favorecer la abstinencia y la adherencia al tratamiento. La abundancia de terapias multicomponente, la falta de especificación de las características clínicas de los participantes durante la intervención, la elevada tasa de abandono o la falta de control experimental de algunos estudios comprometen la posibilidad de considerar las actuales pautas de intervención recomendadas como tratamientos bien establecidos.

Cases of bipolar disorder (BD) with substance use disorder (SUD) have hardly been studied during recent years, particularly in connection with their treatment. Nevertheless, the prevalence of this condition, the costs of care and social costs generated by this population, as well as personal suffering, underline the importance of an effective means of managing this disorder. In the case of SUD in patients with type I BD a prevalence in life of around 52.3–60.7% is calculated, and from 36.5% to 48.1% in the case of type II BD.1,2,3 This type of dual disorder is also associated with a larger presence of medical diseases, long-term hospitalisations and attempted suicides.4,5 It also leads to a high rate of comorbidity with anxiety disorders6 and symptoms such as psychomotor agitation,7 which in turn worsen the prognosis for BD and lead to an increase in the consumption of substances.

Substance consumption has been shown to worsen the psychiatric symptoms of BD by increasing, for example, the frequency of switching between one episode – manic, depressive or mixed – to another.8 Some studies show how the consumption of alcohol by these subjects is associated with increased cognitive deficits, especially in visual and verbal memory and executive functioning and reasoning skills,9,10 while the consumption of tobacco or cannabis seems to be associated with worsening of BD symptoms.11,12 On the other hand, several studies indicate that early abstinence from any consumption is a favourable predictor for the better evolution of an individual with BD.13 In any case, individuals with concomitant diagnoses of BD and SUD usually display greater criminal activity and poorer social functioning than those who are solely bipolar, and they may be comparable to individuals diagnosed as schizophrenic without SUD.14,15

A series of pharmacological treatments have been proposed for the management of this condition. These include lithium,16 Carbamazepine,17 Quetiapine18,19 or Lamotrigine.20 Psychological treatments have also been proposed, such as group, family and cognitive-behavioural therapies, as well as ones to prevent relapse, etc.21,22,23,24 Even so, there seems to be no treatment of proven efficacy for patients of this type. This, together with the typical dichotomy between care systems – for mental health disorders or for drug addiction–, as well as therapeutic approaches (pharmacological or psychological) indicates the need for in-depth analysis of the different interventions that are currently available for these situations. This study has the aim of describing the procedures that have proven to be useful in the treatment of BD with the comorbidity of substance consumption, thereby offering an overview of the current state of research in this field.

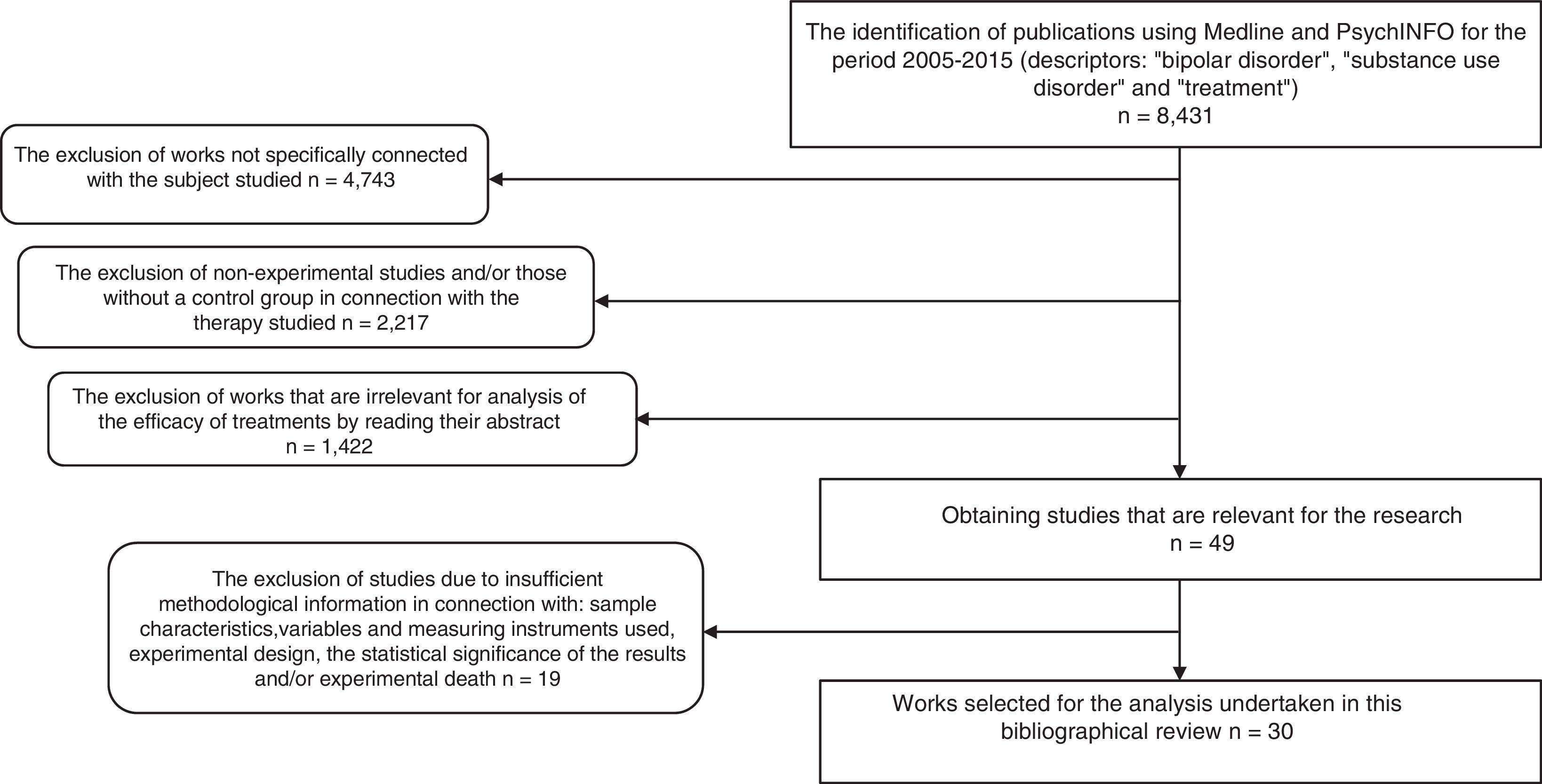

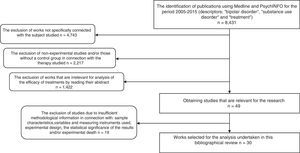

MethodsA general search was carried out (2005–2015) in the Medline and PsychNFO databases, using the following terms as descriptors: (“bipolar disorder” AND “substance use disorder” AND “treatment”). The search was restricted to the last 10 years as this was considered to be a suitable period of time to offer a current view of the subject covered by this work.

As a result, 8431 papers were found. These documents were then screened to select research using the following inclusion criteria: 1) works that aimed to evaluate a form of treatment for BD and SUD; 2) ones that, in connection with the type of therapy studied used the experimental and/or controlled method to determine therapeutic benefit; 3) ones containing clear information on the sample characteristics, variables and the instruments used to measure these, experimental design and the statistical significance of the findings, as well as experimental death; 4) publications in English, Spanish, Italian, French or German. Delimiting using these criteria a total of 30 experimental studies were found, and these are analysed here. Fig. 1 shows the selection process and how studies were excluded.

ResultsOf the 30 experimental studies that fulfilled the methodological criteria applied, 19 refer to pharmacological treatments and 11 refer to psychological treatments. They contain pre- and post-evaluation over a follow-up period of from 2 months to 5 years. The drug consumed the most frequently is alcohol, followed by cocaine, cannabis and methamphetamine. Nevertheless, the majority of the subjects in the samples analysed did not consume a single drug, but rather take several drugs.

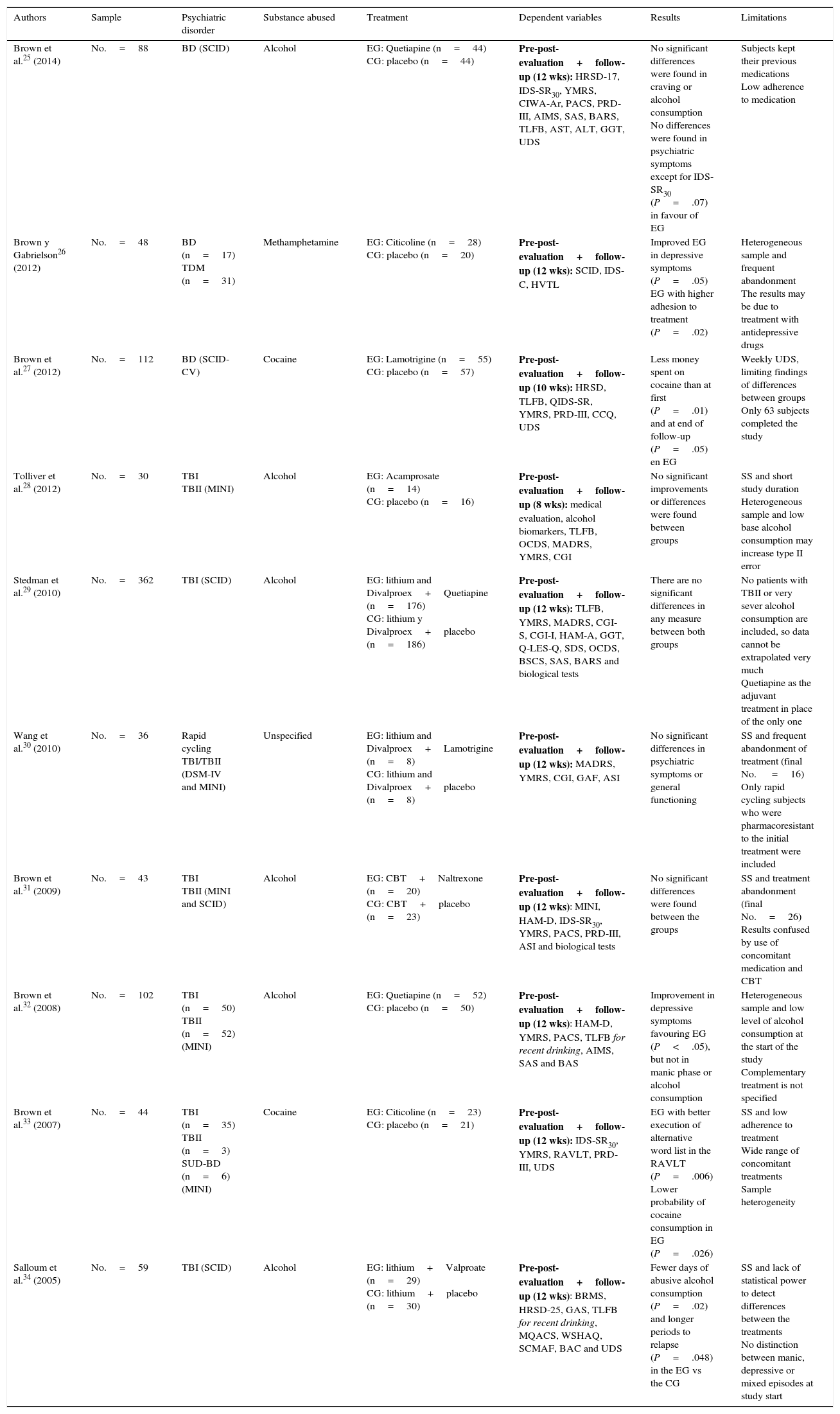

The drugs most frequently used in the pharmacological studies reviewed are Divalproex, Quetiapine and Lamotrigine. The problem of BD as a comorbidity of alcohol consumption is analysed in 6 studies, while 4 other works cover the consumption of other drugs. In all cases a double blind randomised design was used, with a placebo control group25–34 (Table 1).

Randomised experimental studies with a placebo control group and double blind design.

| Authors | Sample | Psychiatric disorder | Substance abused | Treatment | Dependent variables | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al.25 (2014) | No.=88 | BD (SCID) | Alcohol | EG: Quetiapine (n=44) CG: placebo (n=44) | Pre-post-evaluation+follow-up (12 wks): HRSD-17, IDS-SR30, YMRS, CIWA-Ar, PACS, PRD-III, AIMS, SAS, BARS, TLFB, AST, ALT, GGT, UDS | No significant differences were found in craving or alcohol consumption No differences were found in psychiatric symptoms except for IDS-SR30 (P=.07) in favour of EG | Subjects kept their previous medications Low adherence to medication |

| Brown y Gabrielson26 (2012) | No.=48 | BD (n=17) TDM (n=31) | Methamphetamine | EG: Citicoline (n=28) CG: placebo (n=20) | Pre-post-evaluation+follow-up (12 wks): SCID, IDS-C, HVTL | Improved EG in depressive symptoms (P=.05) EG with higher adhesion to treatment (P=.02) | Heterogeneous sample and frequent abandonment The results may be due to treatment with antidepressive drugs |

| Brown et al.27 (2012) | No.=112 | BD (SCID-CV) | Cocaine | EG: Lamotrigine (n=55) CG: placebo (n=57) | Pre-post-evaluation+follow-up (10 wks): HRSD, TLFB, QIDS-SR, YMRS, PRD-III, CCQ, UDS | Less money spent on cocaine than at first (P=.01) and at end of follow-up (P=.05) en EG | Weekly UDS, limiting findings of differences between groups Only 63 subjects completed the study |

| Tolliver et al.28 (2012) | No.=30 | TBI TBII (MINI) | Alcohol | EG: Acamprosate (n=14) CG: placebo (n=16) | Pre-post-evaluation+follow-up (8 wks): medical evaluation, alcohol biomarkers, TLFB, OCDS, MADRS, YMRS, CGI | No significant improvements or differences were found between groups | SS and short study duration Heterogeneous sample and low base alcohol consumption may increase type II error |

| Stedman et al.29 (2010) | No.=362 | TBI (SCID) | Alcohol | EG: lithium and Divalproex+Quetiapine (n=176) CG: lithium y Divalproex+placebo (n=186) | Pre-post-evaluation+follow-up (12 wks): TLFB, YMRS, MADRS, CGI-S, CGI-I, HAM-A, GGT, Q-LES-Q, SDS, OCDS, BSCS, SAS, BARS and biological tests | There are no significant differences in any measure between both groups | No patients with TBII or very sever alcohol consumption are included, so data cannot be extrapolated very much Quetiapine as the adjuvant treatment in place of the only one |

| Wang et al.30 (2010) | No.=36 | Rapid cycling TBI/TBII (DSM-IV and MINI) | Unspecified | EG: lithium and Divalproex+Lamotrigine (n=8) CG: lithium and Divalproex+placebo (n=8) | Pre-post-evaluation+follow-up (12 wks): MADRS, YMRS, CGI, GAF, ASI | No significant differences in psychiatric symptoms or general functioning | SS and frequent abandonment of treatment (final No. =16) Only rapid cycling subjects who were pharmacoresistant to the initial treatment were included |

| Brown et al.31 (2009) | No.=43 | TBI TBII (MINI and SCID) | Alcohol | EG: CBT+Naltrexone (n=20) CG: CBT+placebo (n=23) | Pre-post-evaluation+follow-up (12 wks): MINI, HAM-D, IDS-SR30, YMRS, PACS, PRD-III, ASI and biological tests | No significant differences were found between the groups | SS and treatment abandonment (final No.=26) Results confused by use of concomitant medication and CBT |

| Brown et al.32 (2008) | No.=102 | TBI (n=50) TBII (n=52) (MINI) | Alcohol | EG: Quetiapine (n=52) CG: placebo (n=50) | Pre-post-evaluation+follow-up (12 wks): HAM-D, YMRS, PACS, TLFB for recent drinking, AIMS, SAS and BAS | Improvement in depressive symptoms favouring EG (P<.05), but not in manic phase or alcohol consumption | Heterogeneous sample and low level of alcohol consumption at the start of the study Complementary treatment is not specified |

| Brown et al.33 (2007) | No.=44 | TBI (n=35) TBII (n=3) SUD-BD (n=6) (MINI) | Cocaine | EG: Citicoline (n=23) CG: placebo (n=21) | Pre-post-evaluation+follow-up (12 wks): IDS-SR30, YMRS, RAVLT, PRD-III, UDS | EG with better execution of alternative word list in the RAVLT (P=.006) Lower probability of cocaine consumption in EG (P=.026) | SS and low adherence to treatment Wide range of concomitant treatments Sample heterogeneity |

| Salloum et al.34 (2005) | No.=59 | TBI (SCID) | Alcohol | EG: lithium+Valproate (n=29) CG: lithium+placebo (n=30) | Pre-post-evaluation+follow-up (12 wks): BRMS, HRSD-25, GAS, TLFB for recent drinking, MQACS, WSHAQ, SCMAF, BAC and UDS | Fewer days of abusive alcohol consumption (P=.02) and longer periods to relapse (P=.048) in the EG vs the CG | SS and lack of statistical power to detect differences between the treatments No distinction between manic, depressive or mixed episodes at study start |

AIMS: Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale; ALT: alanine aminotranferase; ASI: Addiction Severity Index; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; BAC: breath alcohol concentration; BARS: Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale; BAS: Barnes Akathisia Scale; BSCS: Brief Substance Craving Scale; BRMS: Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale; CBT: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; CCQ: Cocaine Craving Questionnaire; CGI: Clinical Global Impression (Severity [CGI-S] and Improvement [CGI-I]); CIWA-Ar: Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol revised; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; GAS: Global Assessment Scale; CG: control group; EG: experimental group; GGT: gamma-glutamyltranferase; HAM-A: Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; HAM-D: Hamilton Scale for Depression; HRSD-17: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression-17; HRSD-25: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; HVTL: Hopkins Auditory Verbal Learning Test; IDS-C: Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Clinician-rated; IDS-SR30: Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self-Report 30-item version; MADRS: Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale-25; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MQACS: Modified Quantitative Alcohol Inventory/Craving Scales; OCDS: Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale; PACS: Penn Alcohol Craving Scale; PRD-III: Psychobiology of Recovery in Depression III-Somatic Symptom Scale; QIDS-SR: Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; Q-LES-Q: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire; RAVLT: Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test; SUD-BD: bipolar disorder + schizoaffective disorder; SAS: Simpson-Angus Scale; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview (DSM-IV); SCID-CV: Structured Clinical Interview-Clinical Version (DSM-IV); SCMAF: Symptoms Checklist and Medication Adherence Form; SDS: Sheehan Disability Scale; BD: bipolar disorder; TBI: type I bipolar disorder; TBII: type II bipolar disorder; SDD: severe depression disorder; TLFB: timeline follow-back; SS: sample size; UDS: Urine Drug Screens; WSHAQ: Modified Quantitative Alcohol Inventory/Craving Scales; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale.

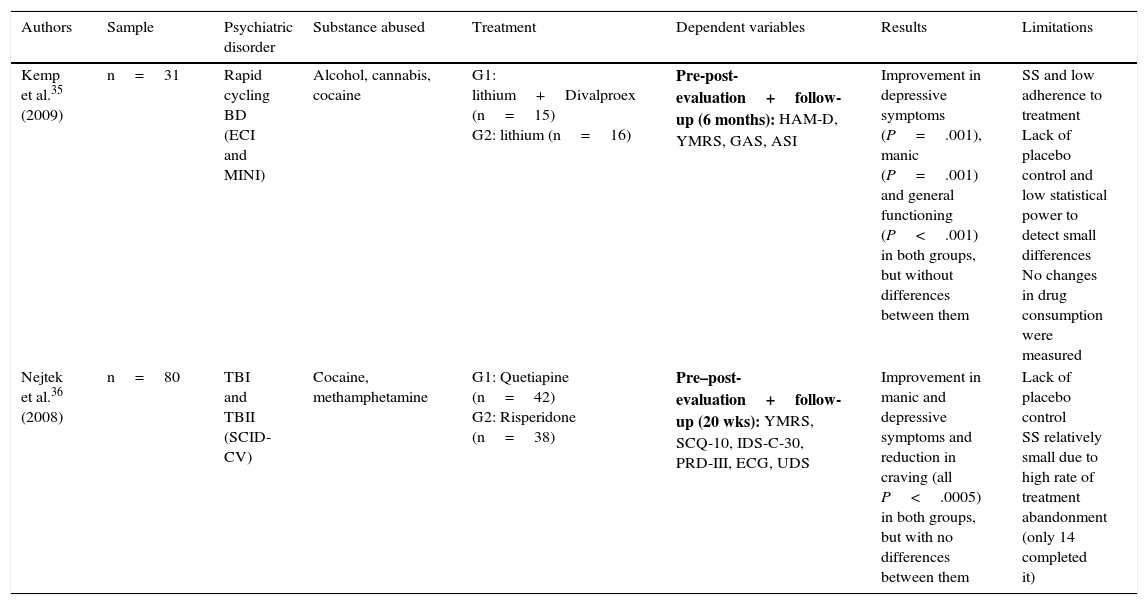

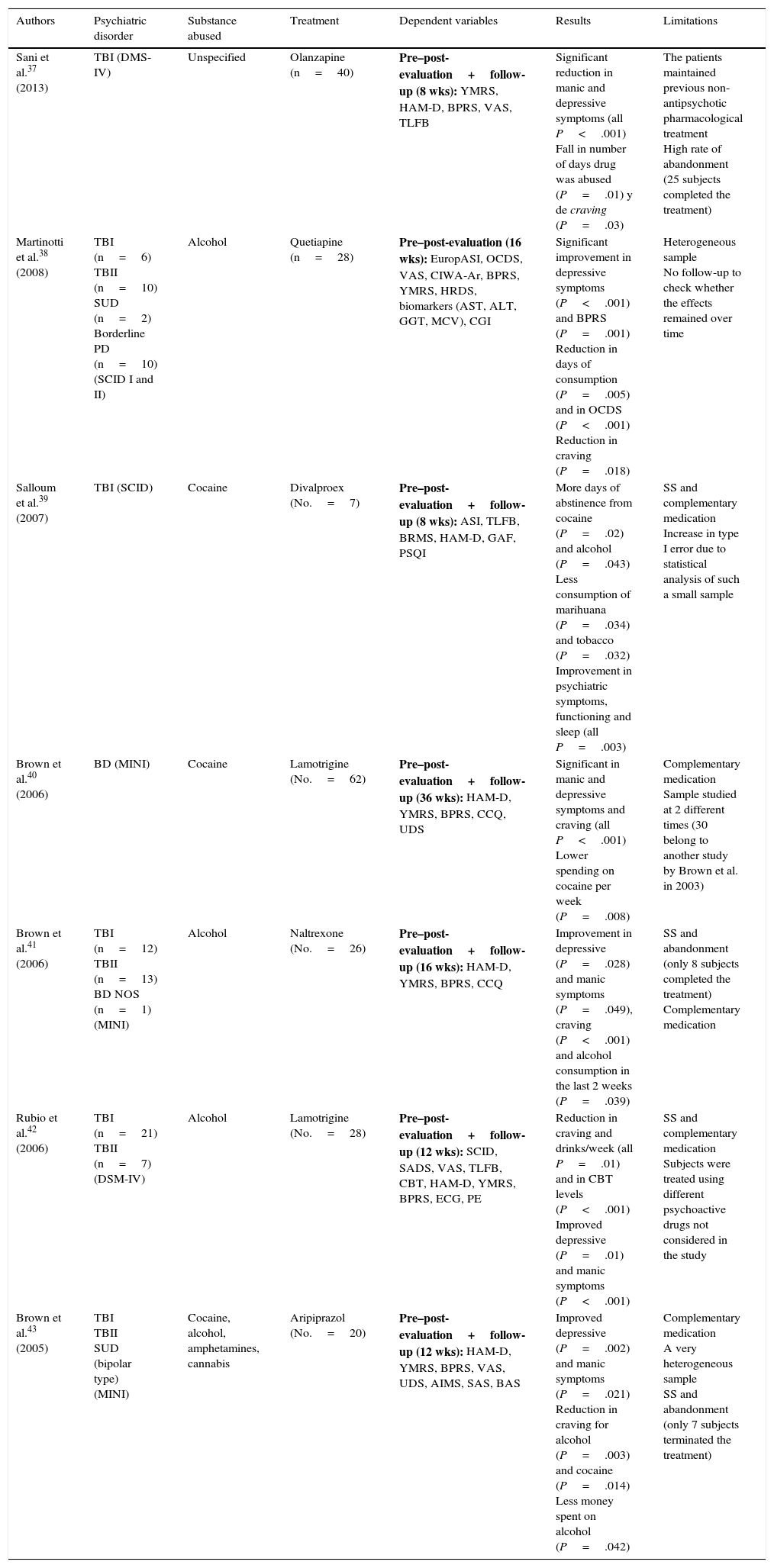

Only 2 experimental studies were found that compared groups with a randomised double blind design,35,36 and the results of these are shown in Table 2. Lastly, 7 quasi-experimental studies with no control group were found that offer better results in reducing psychiatric symptoms, drug consumption and craving. However, these studies have greater methodological limitations37–43 (Table 3).

Randomised experimental studies with parallel groups and double blind design.

| Authors | Sample | Psychiatric disorder | Substance abused | Treatment | Dependent variables | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kemp et al.35 (2009) | n=31 | Rapid cycling BD (ECI and MINI) | Alcohol, cannabis, cocaine | G1: lithium+Divalproex (n=15) G2: lithium (n=16) | Pre-post-evaluation+follow-up (6 months): HAM-D, YMRS, GAS, ASI | Improvement in depressive symptoms (P=.001), manic (P=.001) and general functioning (P<.001) in both groups, but without differences between them | SS and low adherence to treatment Lack of placebo control and low statistical power to detect small differences No changes in drug consumption were measured |

| Nejtek et al.36 (2008) | n=80 | TBI and TBII (SCID-CV) | Cocaine, methamphetamine | G1: Quetiapine (n=42) G2: Risperidone (n=38) | Pre–post-evaluation+follow-up (20 wks): YMRS, SCQ-10, IDS-C-30, PRD-III, ECG, UDS | Improvement in manic and depressive symptoms and reduction in craving (all P<.0005) in both groups, but with no differences between them | Lack of placebo control SS relatively small due to high rate of treatment abandonment (only 14 completed it) |

ASI: Addiction Severity Index; ECG: electrocardiogram; ECI: Extensive Clinical Interview; GAS: Global Assessment Scale; HAM-D: Hamilton Scale for Depression; IDS-C-30: 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician-rated; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; SCID-CV: Structured Clinical Interview-Clinical Version (DSM-IV); SCQ-10: 10-item self-reported Stimulant Craving Questionnaire; PRD-III: Psychobiology of Recovery in Depression III; BD: bipolar disorder; TBI: type I bipolar disorder; TBII: type II bipolar disorder; SS: sample size; UDS: Urine Drug Screens; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale.

Quasi-experimental pharmacological studies.

| Authors | Psychiatric disorder | Substance abused | Treatment | Dependent variables | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sani et al.37 (2013) | TBI (DMS-IV) | Unspecified | Olanzapine (n=40) | Pre–post-evaluation+follow-up (8 wks): YMRS, HAM-D, BPRS, VAS, TLFB | Significant reduction in manic and depressive symptoms (all P<.001) Fall in number of days drug was abused (P=.01) y de craving (P=.03) | The patients maintained previous non-antipsychotic pharmacological treatment High rate of abandonment (25 subjects completed the treatment) |

| Martinotti et al.38 (2008) | TBI (n=6) TBII (n=10) SUD (n=2) Borderline PD (n=10) (SCID I and II) | Alcohol | Quetiapine (n=28) | Pre–post-evaluation (16 wks): EuropASI, OCDS, VAS, CIWA-Ar, BPRS, YMRS, HRDS, biomarkers (AST, ALT, GGT, MCV), CGI | Significant improvement in depressive symptoms (P<.001) and BPRS (P=.001) Reduction in days of consumption (P=.005) and in OCDS (P<.001) Reduction in craving (P=.018) | Heterogeneous sample No follow-up to check whether the effects remained over time |

| Salloum et al.39 (2007) | TBI (SCID) | Cocaine | Divalproex (No.=7) | Pre–post-evaluation+follow-up (8 wks): ASI, TLFB, BRMS, HAM-D, GAF, PSQI | More days of abstinence from cocaine (P=.02) and alcohol (P=.043) Less consumption of marihuana (P=.034) and tobacco (P=.032) Improvement in psychiatric symptoms, functioning and sleep (all P=.003) | SS and complementary medication Increase in type I error due to statistical analysis of such a small sample |

| Brown et al.40 (2006) | BD (MINI) | Cocaine | Lamotrigine (No.=62) | Pre–post-evaluation+follow-up (36 wks): HAM-D, YMRS, BPRS, CCQ, UDS | Significant in manic and depressive symptoms and craving (all P<.001) Lower spending on cocaine per week (P=.008) | Complementary medication Sample studied at 2 different times (30 belong to another study by Brown et al. in 2003) |

| Brown et al.41 (2006) | TBI (n=12) TBII (n=13) BD NOS (n=1) (MINI) | Alcohol | Naltrexone (No.=26) | Pre–post-evaluation+follow-up (16 wks): HAM-D, YMRS, BPRS, CCQ | Improvement in depressive (P=.028) and manic symptoms (P=.049), craving (P<.001) and alcohol consumption in the last 2 weeks (P=.039) | SS and abandonment (only 8 subjects completed the treatment) Complementary medication |

| Rubio et al.42 (2006) | TBI (n=21) TBII (n=7) (DSM-IV) | Alcohol | Lamotrigine (No.=28) | Pre–post-evaluation+follow-up (12 wks): SCID, SADS, VAS, TLFB, CBT, HAM-D, YMRS, BPRS, ECG, PE | Reduction in craving and drinks/week (all P=.01) and in CBT levels (P<.001) Improved depressive (P=.01) and manic symptoms (P<.001) | SS and complementary medication Subjects were treated using different psychoactive drugs not considered in the study |

| Brown et al.43 (2005) | TBI TBII SUD (bipolar type) (MINI) | Cocaine, alcohol, amphetamines, cannabis | Aripiprazol (No.=20) | Pre–post-evaluation+follow-up (12 wks): HAM-D, YMRS, BPRS, VAS, UDS, AIMS, SAS, BAS | Improved depressive (P=.002) and manic symptoms (P=.021) Reduction in craving for alcohol (P=.003) and cocaine (P=.014) Less money spent on alcohol (P=.042) | Complementary medication A very heterogeneous sample SS and abandonment (only 7 subjects terminated the treatment) |

AIMS: Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale; ALT: alanine aminotranferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; BAS: Barnes Akathisia Scale; Borderline PD: borderline personality disorder; BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; BRMS: Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale; CBT: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; CCQ: Cocaine Craving Questionnaire; CGI: Clinical Global Impression (Severity [CGI-S] and Improvement [CGI-I]); CIWA-Ar: Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol revised; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; ECG: electrocardiogram; PE: physical evaluation; EuropASI: European Addiction Severity Index; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; GGT: gamma-glutamyltranferase; HAM-D: Hamilton Scale for Depression; MCV: mean cellular volume; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; OCDS: Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SUD: schizoaffective disorder; SADS: Severity of Alcohol Dependence Scale; SAS: Simpson-Angus Scale; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview (DSM-IV); SCID I: Structured Clinical Interview Axis I (DSM-IV); SCID II: Structured Clinical Interview Axis II (DSM-IV); BD: bipolar disorder; BD NOS: unspecified bipolar disorder; TBI: type I bipolar disorder; type II bipolar disorder; TLFB: timeline follow-back; SS: sample size; UDS: Urine Drug Screens; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale.

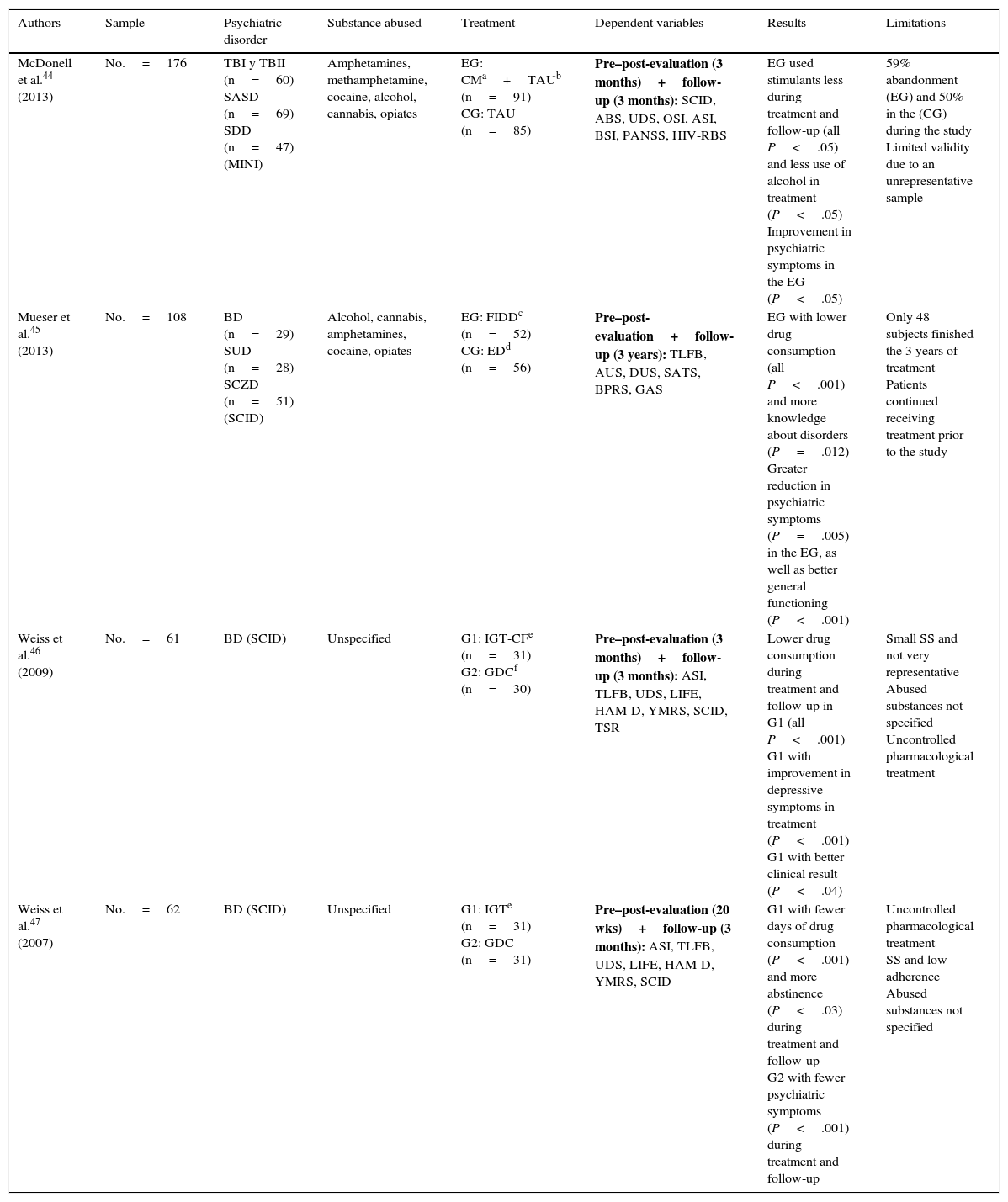

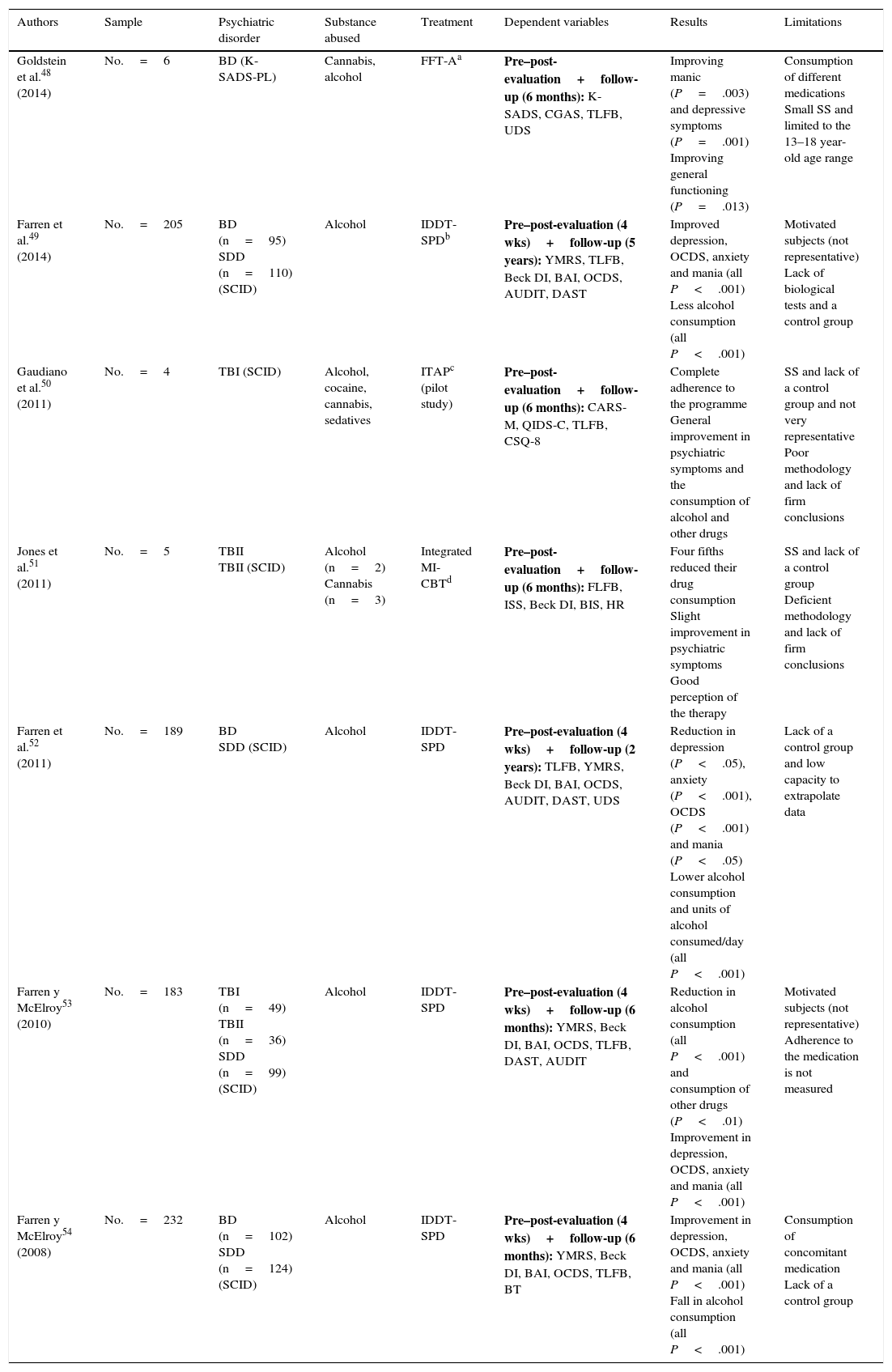

There seems to be no clear treatment pattern for psychological treatment. Table 4 shows 4 randomised experimental studies with parallel groups that examine the efficacy of different techniques,44–47 while Table 5 groups 7 studies that propose and evaluate specific interventions.48–54 However, these studies lack a control group and other methodological guarantees.

Randomised experimental studies with parallel groups.

| Authors | Sample | Psychiatric disorder | Substance abused | Treatment | Dependent variables | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McDonell et al.44 (2013) | No.=176 | TBI y TBII (n=60) SASD (n=69) SDD (n=47) (MINI) | Amphetamines, methamphetamine, cocaine, alcohol, cannabis, opiates | EG: CMa+TAUb (n=91) CG: TAU (n=85) | Pre–post-evaluation (3 months)+follow-up (3 months): SCID, ABS, UDS, OSI, ASI, BSI, PANSS, HIV-RBS | EG used stimulants less during treatment and follow-up (all P<.05) and less use of alcohol in treatment (P<.05) Improvement in psychiatric symptoms in the EG (P<.05) | 59% abandonment (EG) and 50% in the (CG) during the study Limited validity due to an unrepresentative sample |

| Mueser et al.45 (2013) | No.=108 | BD (n=29) SUD (n=28) SCZD (n=51) (SCID) | Alcohol, cannabis, amphetamines, cocaine, opiates | EG: FIDDc (n=52) CG: EDd (n=56) | Pre–post-evaluation+follow-up (3 years): TLFB, AUS, DUS, SATS, BPRS, GAS | EG with lower drug consumption (all P<.001) and more knowledge about disorders (P=.012) Greater reduction in psychiatric symptoms (P=.005) in the EG, as well as better general functioning (P<.001) | Only 48 subjects finished the 3 years of treatment Patients continued receiving treatment prior to the study |

| Weiss et al.46 (2009) | No.=61 | BD (SCID) | Unspecified | G1: IGT-CFe (n=31) G2: GDCf (n=30) | Pre–post-evaluation (3 months)+follow-up (3 months): ASI, TLFB, UDS, LIFE, HAM-D, YMRS, SCID, TSR | Lower drug consumption during treatment and follow-up in G1 (all P<.001) G1 with improvement in depressive symptoms in treatment (P<.001) G1 with better clinical result (P<.04) | Small SS and not very representative Abused substances not specified Uncontrolled pharmacological treatment |

| Weiss et al.47 (2007) | No.=62 | BD (SCID) | Unspecified | G1: IGTe (n=31) G2: GDC (n=31) | Pre–post-evaluation (20 wks)+follow-up (3 months): ASI, TLFB, UDS, LIFE, HAM-D, YMRS, SCID | G1 with fewer days of drug consumption (P<.001) and more abstinence (P<.03) during treatment and follow-up G2 with fewer psychiatric symptoms (P<.001) during treatment and follow-up | Uncontrolled pharmacological treatment SS and low adherence Abused substances not specified |

ABS: Alcohol Breath Samples; ASI: Addiction Severity Index; AUS: Alcohol Use Scale; BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory; CM: contingency management; DUS: Drug Use Scale; ED: Family Education Program; FIDD: Family Intervention for Dual Diagnosis; GAS: Global Assessment Scale; CG: control group; GDC: Group Drug Counselling; EG: experimental group; HAM-D: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; HIV-RBS: HIV Risk Behaviour Scale; IGT: integrated group therapy; IGT-CF: integrated group therapy community friendly; LIFE: longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation; MDD: severe depression disorder; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; OSI: on-site immunoassays; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SUD: schizoaffective disorder; SASD: schizoaffective-spectrum disorder; SATS: Substance Abuse Treatment Scale; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview (DSM-IV); SCZD: schizophrenia; TAU: treatment as usual; BD: bipolar disorder; TBI: type I bipolar disorder; TBII: type II bipolar disorder; SDD: severe depression disorder; TLFB: timeline follow-back; SS: sample size; TSR: treatment services review; UDS: Urine Drug Screens; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale.

Weekly care by the social and mental health services with psychiatric medication and group therapy (without specifying which drugs or therapies).

Composed of psycho-education, training in communications skills and problem solving, role-playing, motivational interviews and relapse prevention. Acting on both diagnoses.

Composed of extensive psycho-education (disorders, vulnerability-stress model, personal experiences, the educational presentation of information and discussions, etc.).

Quasi-experimental psychological studies.

| Authors | Sample | Psychiatric disorder | Substance abused | Treatment | Dependent variables | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goldstein et al.48 (2014) | No.=6 | BD (K-SADS-PL) | Cannabis, alcohol | FFT-Aa | Pre–post-evaluation+follow-up (6 months): K-SADS, CGAS, TLFB, UDS | Improving manic (P=.003) and depressive symptoms (P=.001) Improving general functioning (P=.013) | Consumption of different medications Small SS and limited to the 13–18 year-old age range |

| Farren et al.49 (2014) | No.=205 | BD (n=95) SDD (n=110) (SCID) | Alcohol | IDDT-SPDb | Pre–post-evaluation (4 wks)+follow-up (5 years): YMRS, TLFB, Beck DI, BAI, OCDS, AUDIT, DAST | Improved depression, OCDS, anxiety and mania (all P<.001) Less alcohol consumption (all P<.001) | Motivated subjects (not representative) Lack of biological tests and a control group |

| Gaudiano et al.50 (2011) | No.=4 | TBI (SCID) | Alcohol, cocaine, cannabis, sedatives | ITAPc (pilot study) | Pre–post-evaluation+follow-up (6 months): CARS-M, QIDS-C, TLFB, CSQ-8 | Complete adherence to the programme General improvement in psychiatric symptoms and the consumption of alcohol and other drugs | SS and lack of a control group and not very representative Poor methodology and lack of firm conclusions |

| Jones et al.51 (2011) | No.=5 | TBII TBII (SCID) | Alcohol (n=2) Cannabis (n=3) | Integrated MI-CBTd | Pre–post-evaluation+follow-up (6 months): FLFB, ISS, Beck DI, BIS, HR | Four fifths reduced their drug consumption Slight improvement in psychiatric symptoms Good perception of the therapy | SS and lack of a control group Deficient methodology and lack of firm conclusions |

| Farren et al.52 (2011) | No.=189 | BD SDD (SCID) | Alcohol | IDDT-SPD | Pre–post-evaluation (4 wks)+follow-up (2 years): TLFB, YMRS, Beck DI, BAI, OCDS, AUDIT, DAST, UDS | Reduction in depression (P<.05), anxiety (P<.001), OCDS (P<.001) and mania (P<.05) Lower alcohol consumption and units of alcohol consumed/day (all P<.001) | Lack of a control group and low capacity to extrapolate data |

| Farren y McElroy53 (2010) | No.=183 | TBI (n=49) TBII (n=36) SDD (n=99) (SCID) | Alcohol | IDDT-SPD | Pre–post-evaluation (4 wks)+follow-up (6 months): YMRS, Beck DI, BAI, OCDS, TLFB, DAST, AUDIT | Reduction in alcohol consumption (all P<.001) and consumption of other drugs (P<.01) Improvement in depression, OCDS, anxiety and mania (all P<.001) | Motivated subjects (not representative) Adherence to the medication is not measured |

| Farren y McElroy54 (2008) | No.=232 | BD (n=102) SDD (n=124) (SCID) | Alcohol | IDDT-SPD | Pre–post-evaluation (4 wks)+follow-up (6 months): YMRS, Beck DI, BAI, OCDS, TLFB, BT | Improvement in depression, OCDS, anxiety and mania (all P<.001) Fall in alcohol consumption (all P<.001) | Consumption of concomitant medication Lack of a control group |

AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; Beck DI: Beck Depression Inventory; BIS: Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; BT: Blood Test; CARS-M: Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania; CBT: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; CGAS: Children's Global Assessment Scale; CSQ-8: Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8; DAST: Drub Abuse Screening Test; FFT-A: Family-Focused Treatment for Adolescents; HR: Helpfulness Ratings; IDDT-SPD: Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (St. Patrick, Dublin); ISS: Internal States Scale; ITAP: Improving Treatment Adherence Program; K-SADS: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; K-SADS-PL: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime Version; MDD: severe depression disorder; MI-CBT: Motivational Interviewing-Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; OCDS: Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale; QIDS-C: Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician Version; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview (DSM-IV); BD: bipolar disorder; TBI: type I bipolar disorder; type II bipolar disorder; SDD: severe depression disorder; TLFB: timeline follow-back; SS: sample size; UDS: Urine Drug Screens; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale.

Training in psycho-education, communication, problem solving, relapse prevention, involving family members and close friends. Acting on both diagnoses, encouraging adherence to medication (9months).

Based on FIRESIDE. This is composed of a first phase of stabilisation and detoxification followed by another phase of psycho-education, individual, interpersonal and support therapy, with AA sessions and other discussion groups and the prevention of relapses (7–8 months).

The majority of the studies analysed centre their results on measurements of psychiatric symptoms and substance consumption. The tests used to quantify these variables largely agree on using the Young Mania Rating Scale,55 while a very wide range of instruments are used to measure drug consumption and depression, and little information is offered on the reliability of the tests used. Moreover, a number of questions are ignored, such as adhesion to treatment or participant perceived efficacy and their satisfaction with the intervention. These conditions are especially important given the high rate of treatment abandonment and the lack of subject involvement and motivation in interventions.

DiscussionThis review aims to show the current therapeutic panorama in the treatment of BD and SUD cases. The utility of pharmacological and psychological interventions is evaluated based on analysis of the methodological reliability of the experimental studies published during the past decade. It was therefore found that Valproate34 and Lamotrigine27 may be useful in reducing the consumption of alcohol and other drugs, respectively. Quetiapine is used as the sole or main drug to relieve psychiatric symptoms and craving,32,36,38 and Risperidone36 or Olanzapine37 have also given good results. Nevertheless, Citicoline has been shown to treat these symptoms while also favouring better adhesion to the treatment,26 although these results are not confirmed by other work groups.33 In studies of rapid cycling BD patients Lamotrigine was not found to be effective,27 and the classic treatment with lithium was shown to be effective in the treatment of psychiatric symptoms.33 These studies base their conclusions on the use of a control group and the use of similar tests or instruments to measure the dependent variables, although their samples are sometimes small and suffer high rates of abandonment.

In the light of these studies it could be said that Quetiapine is the drug most solidly associated with an improvement in the psychiatric symptoms of BD, while a combination of lithium and Valproate is the most effective in reducing the consumption of alcohol and relapses. Even so, many works are contradictory and use different ways of measuring variables as well as different samples and concomitant medication which may explain the said differences. The studies without a double blind design offer promising results for all f the drugs, and this may be due to reduced control of the experimental situation, leading to lower internal validity. It is therefore recommendable to verify these results using studies that are methodologically sounder before stating that treatments are effective.

Apart from the fact that there are fewer studies of psychological interventions than is the case for pharmacological ones, they are tested by smaller-scale studies with more methodological limitations. They often lack a control group and use small samples with major experimental death. When different interventions are compared, community friendly integrated group therapy was found to be more effective than advisory groups on drugs, helping to reduce substance consumption and psychiatric symptoms, while giving a better clinical result in general.46 Nevertheless, the drug advisory group and integrated group therapy were apparently effective in treating BD.47 The management of contingencies was also found suitable for reducing the consumption of alcohol and stimulants, and it also increased the improvement in manic and depressive symptoms.44 Likewise, intervention in the family for bipolar pathology was found to be more beneficial in terms of education about disorders, psychiatric symptoms and the severity of consumption than family education.45 Other studies without a control group also gave promising results, although as in the case of pharmacological treatment, methodologically more rigorous studies are needed to confirm efficacy.

Practically all of the psychological interventions use an integrated approach to cover both diagnoses. Several authors44,45 support these principles, as they understand it to be more correct to consider both diagnoses as interrelated, given that they often appear together.1,2,3 In the light of this apparently widespread premise, it is surprising that there are no studies which try to evaluate the efficacy of combined pharmacological and psychological treatments, comparing their results with those of a single isolated treatment. It would seem reasonable to think that, due to the complexity of the psychopathology and the presumed consensus on a comprehensive approach, a complementary intervention with broad action on all of the aspects of the problem may be the best choice.

It should also be underlined that all of these psychological treatments were part of what are known as “multicomponent” therapies. This means that all of them were composed of several active components which together were used to treat all possible aspects for intervention. However, this gives rise to an important restriction, as it is impossible to know which components caused the efficacy shown. This recurring problem has yet to be resolved in the study of some psychological interventions, and researchers are asked to isolate the said therapeutic ingredients and to examine how they influence the benefits of the final result.

Another major limitation in all of the studies reviewed that may explain differences in results to a certain extent is that they fail to consider the phase–depressive, manic or mixed–in which the subjects are at all times of the intervention (the start, duration and end, or the follow-up period). Some drugs are known to be more suitable than others depending on the phase the patient is in. Kosten and Kosten56 describe the key aspects of an ideal medication for these cases: low risk, infrequent doses, good tolerability and few side effects. They therefore suggest Valproate or Carbamazepine as suitable drugs for the manic phase, while they consider antidepressive drugs to be more suitable during the depressive phase. Nevertheless, the effect of these drugs has not been tested in comparison with psychological treatments, and nor has the improvement that may arise from combined treatment been sufficiently evaluated in comparison with one that only uses drugs or psychotherapy.

The lack of an experimental control group in many cases is also a major restriction that may distort their results, and some studies even fail to properly specify the variables measured or the significance of their data,57 or they fail to take the use of concomitant drugs into account when drawing conclusions. Nor do they take into account the differences between the doses administered to each subject depending on the severity of the disorder. It should be pointed out here that these studies often fail to specify the severity of patient symptoms, so that including all of the patients in a single study may affect the reliability of the resulting data. The same situation arises with the drugs patients take, as most of them are addicted to multiple drugs with different levels of abuse or dependency. The fact that all of the drugs they take are considered to be equivalent is forgotten, as they are not described separately in the analysis of results.

Another and perhaps the largest problem with the studies reviewed is their high rate of abandonment by subjects. All of the studies reviewed report this, and it has been widely described as an important drawback for bipolar disorder in general.58 Predictors of abandonment have even been described, such as a recent manic, depressive or mixed episode and a low educational level,59 as well as the presence of personality disorders, psychotic symptoms or lithium treatment.60 Designing a specific programme that trains and involves subjects in their treatment could be a qualitative improvement that would encourage their stability and adherence. The creation of a complementary intervention that rewards adhesion to the main treatment using such a programme could also be useful.50

It therefore seems to be of especial interest to develop new studies that examine in depth the efficacy of different approaches to the treatment of the psychiatric disorder and also encourage early abstinence and detoxification from the drugs consumed.13 It would therefore also be prudent to use early detection and prevention based on sociodemographic risk factors, such as male sex, youth, low educational level, previous diagnosis of a mood disorder or a parental history of SUD,61–63 together with other recently suggested risk factors such as a history of sexual or physical abuse.64

To conclude, we underline the need to increase the methodological rigour of research studies, specifying the variables and measuring instruments, using large samples with a control group, controlling distorting variables such as complementary treatments or poor delimitation of subject severity, rigorously measuring adhesion to treatment and the potential influence of some aspects of the intervention on abandonment, as well as unifying the criteria and methods used to quantify drug consumption or psychiatric symptoms. As treatments of choice, Quetiapine and Valproate have been shown to be superior in improving psychiatric symptoms and reducing alcohol consumption, respectively, while psychological group therapies with psycho-education, preventing relapses and including the family have also proven beneficial in reducing symptoms and aiding abstinence and adherence to the treatment. Although some studies state that these forms of intervention are to be preferred, the current literature shows that there is no single well-established treatment for this condition.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Secades-Álvarez A, Fernández-Rodríguez C. Revisión de la eficacia de los tratamientos para el trastorno bipolar en comorbilidad con el abuso de sustancias. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2017;10:113–124