Suicide is the primary cause of unnatural death in our country. All efforts aimed at better prediction and prevention of suicide attempts are an indirect way to lower the number of completed suicides.1 Despite the numerous efforts made to date, current psychiatry bases its diagnoses on observations and descriptions of behaviour,2 but it is to be hoped that future precision psychiatry will evolve to using risk algorithms and individualisation, offering all patients a personalised perspective.3 Recent studies have shown that various cognitive impairments might be related to suicidal vulnerability, these include: working memory deficits, verbal fluency, problem-solving, inhibition, cognitive flexibility, and emotional recognition.4 It is well known that the latter is a central component of non-verbal communication, and difficulties in this area are a crucial factor in social competence, interpersonal functioning and quality of life. This skill not only encompasses the interpretation of social emotions, but also the skill to deal with emotional consequences, which can be a key factor in suicidal behaviour.5 The interpretation of facial expressions seems to be congruent with mood, since it has been proven that in patients diagnosed with depression there is a tendency to value positive, ambiguous or neutral facial expressions in a more negative way.6 More specifically, patients with a personal history of suicide attempt tend to commit significantly more errors in emotional recognition compared to healthy controls,7 and specifically display particular difficulty in evaluating emotional expressions of anger.8

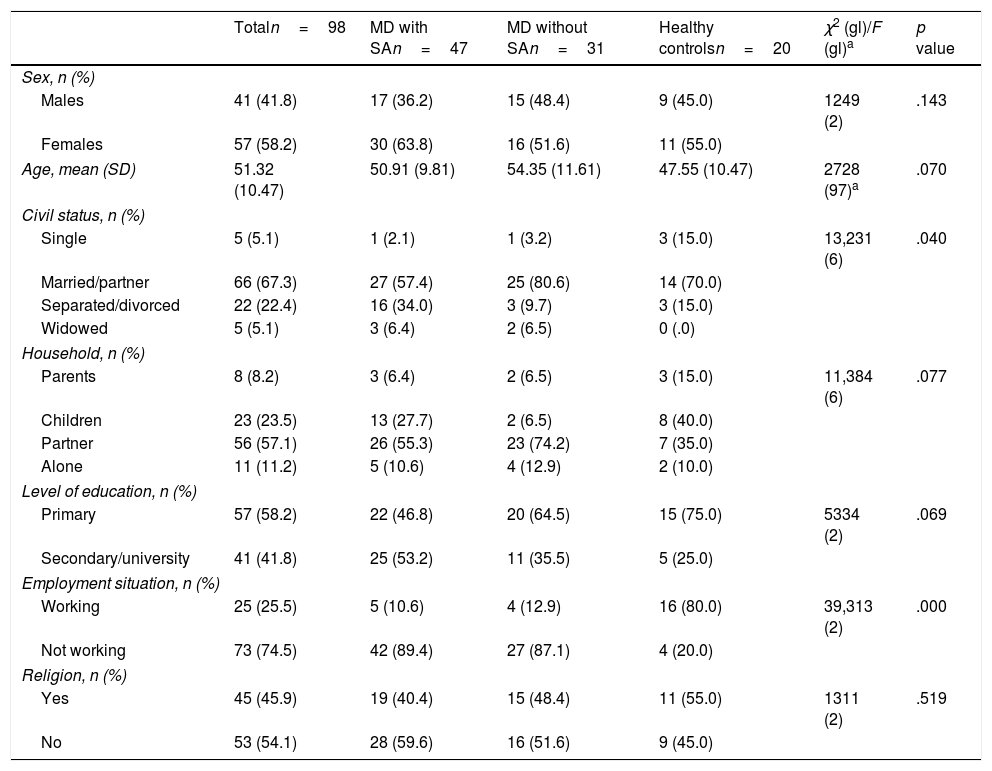

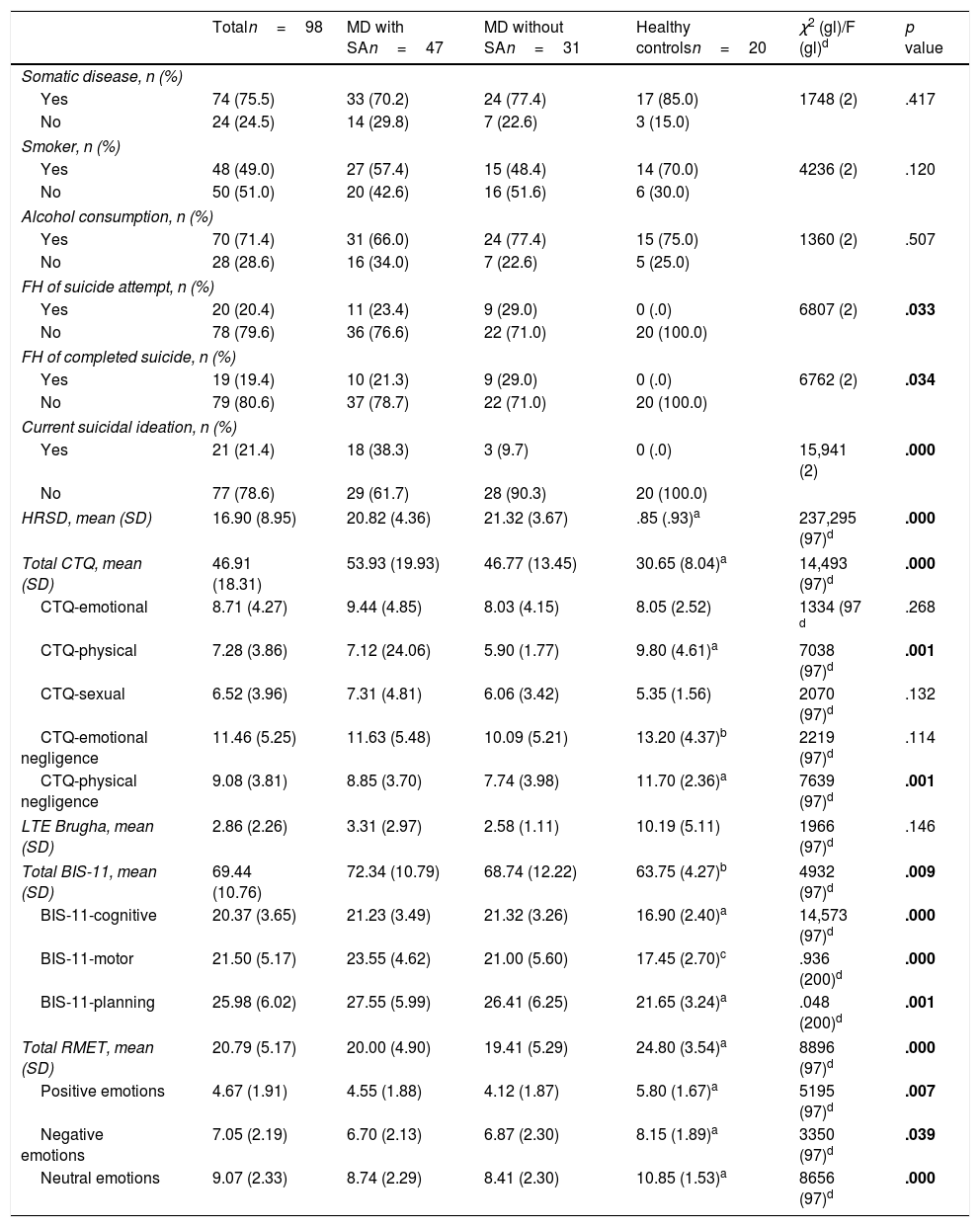

The main aim of this study was to determine whether there are impairments in emotional recognition that are specifically associated with suicidal behaviour. To that end, a sample of 98 people was studied, grouped as follows: patients with a DSM-5 diagnosis of major depression (MD), and a history of a previous suicide attempt (SA), n=47, group 1 (mean age [SD]=50.91 [9.81]; females: 63.8%), patients with MD with no previous SA, n=31, group 2 (mean age [SD]=54.35 [11.61]; females: 51.6%) and a healthy control group, n=19, group 3 (mean age [SD]=47.55 [10.47]; females: 55.0%). All the participants were assessed using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD),9 and the “reading the mind in the eyes” test (RMET).10 Both groups of patients diagnosed with depression were similar in terms of severity (HRSD group 1=20.82 [4.36] vs. HRSD group 2=21.32 [3.67], t=−.519, p=.605). Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. The results obtained using the RMET are shown in Table 2. As can be observed from Table 2, after the appropriate ANOVA test was carried out, the patients of groups 1 and 2 differed significantly from group 3 (healthy controls) in both total score and the recognition of positive, negative or neutral emotions. However, no statistically significant differences were found in any case between groups 1 and 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

| Totaln=98 | MD with SAn=47 | MD without SAn=31 | Healthy controlsn=20 | χ2 (gl)/F (gl)a | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Males | 41 (41.8) | 17 (36.2) | 15 (48.4) | 9 (45.0) | 1249 (2) | .143 |

| Females | 57 (58.2) | 30 (63.8) | 16 (51.6) | 11 (55.0) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 51.32 (10.47) | 50.91 (9.81) | 54.35 (11.61) | 47.55 (10.47) | 2728 (97)a | .070 |

| Civil status, n (%) | ||||||

| Single | 5 (5.1) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (15.0) | 13,231 (6) | .040 |

| Married/partner | 66 (67.3) | 27 (57.4) | 25 (80.6) | 14 (70.0) | ||

| Separated/divorced | 22 (22.4) | 16 (34.0) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| Widowed | 5 (5.1) | 3 (6.4) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (.0) | ||

| Household, n (%) | ||||||

| Parents | 8 (8.2) | 3 (6.4) | 2 (6.5) | 3 (15.0) | 11,384 (6) | .077 |

| Children | 23 (23.5) | 13 (27.7) | 2 (6.5) | 8 (40.0) | ||

| Partner | 56 (57.1) | 26 (55.3) | 23 (74.2) | 7 (35.0) | ||

| Alone | 11 (11.2) | 5 (10.6) | 4 (12.9) | 2 (10.0) | ||

| Level of education, n (%) | ||||||

| Primary | 57 (58.2) | 22 (46.8) | 20 (64.5) | 15 (75.0) | 5334 (2) | .069 |

| Secondary/university | 41 (41.8) | 25 (53.2) | 11 (35.5) | 5 (25.0) | ||

| Employment situation, n (%) | ||||||

| Working | 25 (25.5) | 5 (10.6) | 4 (12.9) | 16 (80.0) | 39,313 (2) | .000 |

| Not working | 73 (74.5) | 42 (89.4) | 27 (87.1) | 4 (20.0) | ||

| Religion, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 45 (45.9) | 19 (40.4) | 15 (48.4) | 11 (55.0) | 1311 (2) | .519 |

| No | 53 (54.1) | 28 (59.6) | 16 (51.6) | 9 (45.0) | ||

SD: standard deviation; MD: major depression; SA: suicide attempt.

Clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Totaln=98 | MD with SAn=47 | MD without SAn=31 | Healthy controlsn=20 | χ2 (gl)/F (gl)d | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic disease, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 74 (75.5) | 33 (70.2) | 24 (77.4) | 17 (85.0) | 1748 (2) | .417 |

| No | 24 (24.5) | 14 (29.8) | 7 (22.6) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| Smoker, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 48 (49.0) | 27 (57.4) | 15 (48.4) | 14 (70.0) | 4236 (2) | .120 |

| No | 50 (51.0) | 20 (42.6) | 16 (51.6) | 6 (30.0) | ||

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 70 (71.4) | 31 (66.0) | 24 (77.4) | 15 (75.0) | 1360 (2) | .507 |

| No | 28 (28.6) | 16 (34.0) | 7 (22.6) | 5 (25.0) | ||

| FH of suicide attempt, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 20 (20.4) | 11 (23.4) | 9 (29.0) | 0 (.0) | 6807 (2) | .033 |

| No | 78 (79.6) | 36 (76.6) | 22 (71.0) | 20 (100.0) | ||

| FH of completed suicide, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 19 (19.4) | 10 (21.3) | 9 (29.0) | 0 (.0) | 6762 (2) | .034 |

| No | 79 (80.6) | 37 (78.7) | 22 (71.0) | 20 (100.0) | ||

| Current suicidal ideation, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 21 (21.4) | 18 (38.3) | 3 (9.7) | 0 (.0) | 15,941 (2) | .000 |

| No | 77 (78.6) | 29 (61.7) | 28 (90.3) | 20 (100.0) | ||

| HRSD, mean (SD) | 16.90 (8.95) | 20.82 (4.36) | 21.32 (3.67) | .85 (.93)a | 237,295 (97)d | .000 |

| Total CTQ, mean (SD) | 46.91 (18.31) | 53.93 (19.93) | 46.77 (13.45) | 30.65 (8.04)a | 14,493 (97)d | .000 |

| CTQ-emotional | 8.71 (4.27) | 9.44 (4.85) | 8.03 (4.15) | 8.05 (2.52) | 1334 (97 d | .268 |

| CTQ-physical | 7.28 (3.86) | 7.12 (24.06) | 5.90 (1.77) | 9.80 (4.61)a | 7038 (97)d | .001 |

| CTQ-sexual | 6.52 (3.96) | 7.31 (4.81) | 6.06 (3.42) | 5.35 (1.56) | 2070 (97)d | .132 |

| CTQ-emotional negligence | 11.46 (5.25) | 11.63 (5.48) | 10.09 (5.21) | 13.20 (4.37)b | 2219 (97)d | .114 |

| CTQ-physical negligence | 9.08 (3.81) | 8.85 (3.70) | 7.74 (3.98) | 11.70 (2.36)a | 7639 (97)d | .001 |

| LTE Brugha, mean (SD) | 2.86 (2.26) | 3.31 (2.97) | 2.58 (1.11) | 10.19 (5.11) | 1966 (97)d | .146 |

| Total BIS-11, mean (SD) | 69.44 (10.76) | 72.34 (10.79) | 68.74 (12.22) | 63.75 (4.27)b | 4932 (97)d | .009 |

| BIS-11-cognitive | 20.37 (3.65) | 21.23 (3.49) | 21.32 (3.26) | 16.90 (2.40)a | 14,573 (97)d | .000 |

| BIS-11-motor | 21.50 (5.17) | 23.55 (4.62) | 21.00 (5.60) | 17.45 (2.70)c | .936 (200)d | .000 |

| BIS-11-planning | 25.98 (6.02) | 27.55 (5.99) | 26.41 (6.25) | 21.65 (3.24)a | .048 (200)d | .001 |

| Total RMET, mean (SD) | 20.79 (5.17) | 20.00 (4.90) | 19.41 (5.29) | 24.80 (3.54)a | 8896 (97)d | .000 |

| Positive emotions | 4.67 (1.91) | 4.55 (1.88) | 4.12 (1.87) | 5.80 (1.67)a | 5195 (97)d | .007 |

| Negative emotions | 7.05 (2.19) | 6.70 (2.13) | 6.87 (2.30) | 8.15 (1.89)a | 3350 (97)d | .039 |

| Neutral emotions | 9.07 (2.33) | 8.74 (2.29) | 8.41 (2.30) | 10.85 (1.53)a | 8656 (97)d | .000 |

FH: family history; BIS-11: Barratt impulsiveness scale; CTQ: childhood trauma questionnaire; SD: standard deviation; MD: major depression; HRSD: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; LTE: list of threatening experiences; RMET: Reading the mind in the eyes; SA: suicide attempt.

It is important to note that, in contrast to Richard-Devantoy et al.,11 the patients with a history of a previous SA did not perform less well in the emotional recognition of negative emotions (disgust) when compared to patients with similar clinical characteristics, but without a history of SA. However, our results are consistent with those that suggest that patients with a history of SA perform this task less well than the corresponding healthy controls.5,7

The present study adds to previous knowledge on the subject by demonstrating that emotional recognition impairments are not specifically associated with suicidal behaviour, at least in MD. Due to this study's sample size and the possibility of type II error, our results must be considered with appropriate caution.

FundingThis study was financed by the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness through the Carlos III Health Institute (FIS PI14/02029), the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), and, partially, by the Biomedical Research Centre in Mental Health Network.

Please cite this article as: Velasco Á, Rodríguez-Revuelta J, de la Fuente-Tomás L, Fernández-Peláez AD, Dal Santo F, Jiménez-Treviño L, et al. ¿Es la alteración en el reconocimiento emocional un factor de riesgo específico de tentativa suicida? Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2018.06.002