Candida albicans chorioretinitis is the most common cause of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Echinocandins are recommended as first-line therapy in the treatment of invasive candidiasis (IC), but in clinically stable patients with IC and endophthalmitis caused by Candida species susceptible to azole compounds these are the first-line treatment due to their better intraocular penetration.

Case reportA 42-year-old woman admitted to hospital for duodenal perforation after gastrointestinal surgery and treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics developed C. albicans candidemia. According to protocol, an antifungal treatment with anidulafungin was given. The patient presented no visual symptoms but on routinary ophthalmoscopic examination multiple bilateral chorioretinal lesions were observed. Systemic therapy was changed to fluconazole, with good systemic and ocular results.

ConclusionsAzole compounds are the first-line therapy for endophthalmitis associated with candidemia. However, clinical guidelines often propose echinocandins as the first option for IC. In some cases, C. albicans chorioretinitis will require a change in the systemic treatment to assure better intraocular penetration. According to the current evidence and our own experience, routine funduscopy is not necessary in all IC patients. However, we do recommend fundus examination in patients with visual symptoms or those unable to report them (paediatric patients and patients with an altered level of consciousness), and in those who are being treated with echinocandins in monotherapy.

La coriorretinitis por Candida albicans es la forma más frecuente de endoftalmitis endógena fúngica. En la enfermedad invasora por Candida (EIC), las equinocandinas son la primera opción de tratamiento, pero en pacientes con EIC clínicamente estables, con endoftalmitis y con un aislamiento de Candida sin resistencia a los azoles, son estos últimos los antifúngicos de elección por su mejor penetración intraocular.

Caso clínicoSe presenta el caso de una mujer de 42 años con perforación duodenal posquirúrgica, antibioterapia intravenosa de amplio espectro y candidemia por C. albicans bajo tratamiento con anidulafungina. Aunque no presenta alteraciones visuales, se realiza exploración rutinaria del fondo de ojo, donde se observan múltiples lesiones coriorretinianas bilaterales. Se cambia el tratamiento a fluconazol, con buena evolución sistémica y ocular.

ConclusionesLas guías clínicas indican un tratamiento empírico inicial con equinocandinas para tratar la EIC. En caso de presentar coriorretinitis por C. albicans multisensible es recomendable un cambio de tratamiento a azoles sistémico para asegurar una adecuada concentración antifúngica intraocular. Con la evidencia actual y en nuestra experiencia no es necesaria la exploración rutinaria del fondo de ojo en todos los pacientes con EIC. Esta puede reservarse a pacientes con síntomas visuales, a pacientes incapaces de referir de manera precoz cualquier síntoma (pacientes pediátricos o aquellos con el nivel de conciencia alterado), o a pacientes tratados exclusivamente con equinocandinas.

Endogenous endophthalmitis is an intraocular infection resulting from haematogenous spread of an infectious agent from a primary source. Candidemia is the most frequent cause of fungal endogenous endophthalmitis. The term “candidemia” describes the presence of Candida in the bloodstream, and is the cause of invasive candidiasis (IC).14Candida albicans is the most frequently isolated species causing intraocular infection, but Candida glabrata, Candidaparapsilosis, Candida tropicalis and Candida krusei have also been reported.2,6

Candida reaches the choroid firstly, where it settles and develops a choroiditis between the 3rd and 15th day of fungemia.14 It progresses affecting the retina (chorioretinitis) and causes mild vitreous inflammation afterwards. Without treatment, it progresses to the vitreous and produces an endophthalmitis. Chorioretinitis is generally asymptomatic, except when it affects the fovea. It has bilateral involvement in 67% of the cases, with multifocal lesions in 80%.2,14

A 42-year-old woman was admitted to hospital after presenting duodenal perforation secondary to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. A wide-spectrum antibiotic therapy was started. After two weeks, the patient developed fever and hypotension. Blood culture (samples from peripheral blood and central venous catheter) yielded a C. albicans isolate susceptible to all the antifungals tested. Following current clinical guidelines, intravenous anidulafungin was administered (200mg loading dose on day one, followed by 100mg daily).

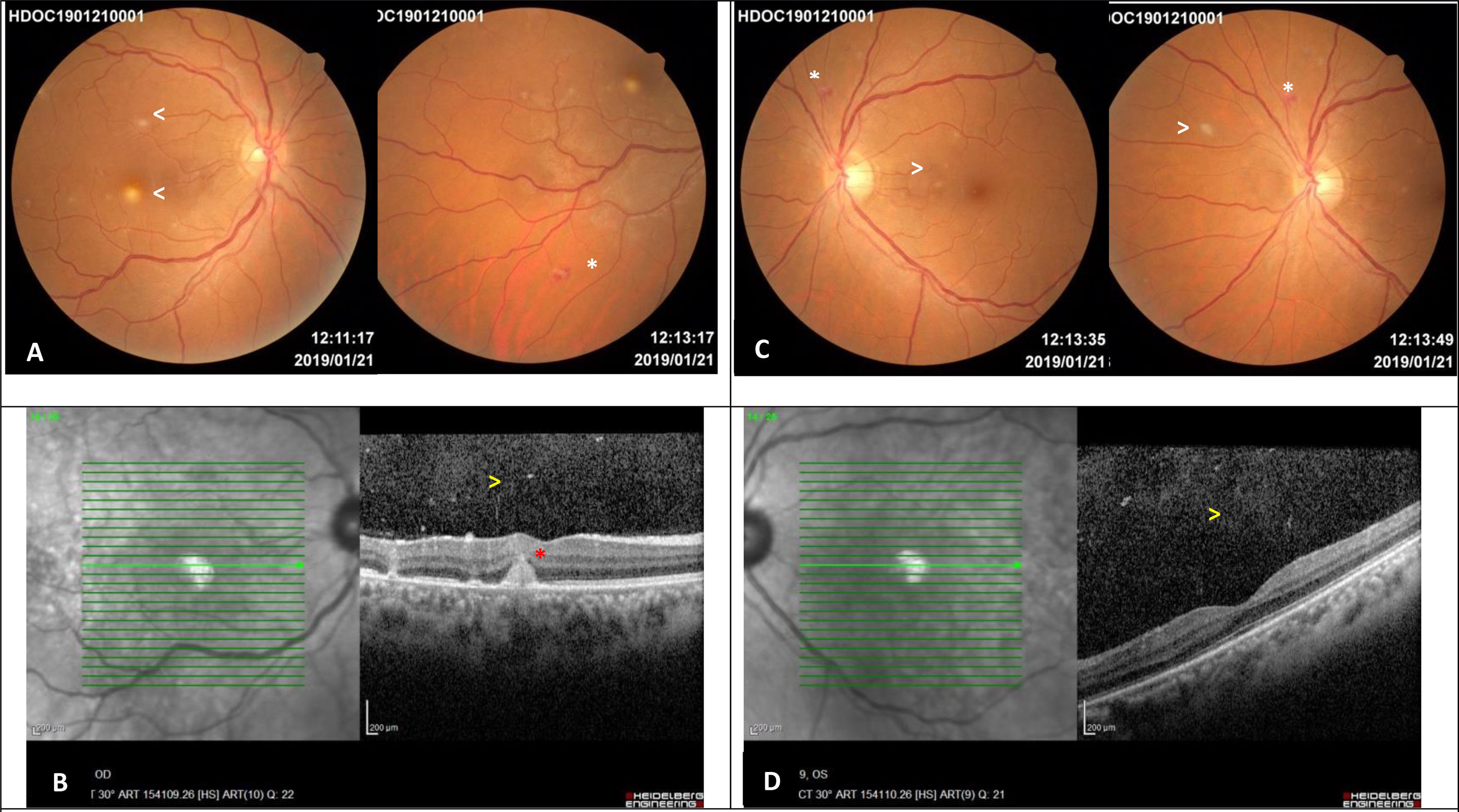

Despite being asymptomatic, a routine ophthalmoscopic examination was performed. We observed multiple, small, round, deep focal yellow-white infiltrative chorioretinal lesions in both eyes. In addition, other non-specific lesions, such as Roth spots, were found. Macular spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) of the right eye showed a parafoveal chorioretinal lesion which did not involved the outer retina (Fig. 1). In view of these findings, the diagnosis of Candida chorioretinitis was made. Due to its better intraocular penetration, the antifungal treatment was changed to oral fluconazol (800mg loading dose on day one, followed by 400mg daily for one month). The patient progressed favourably.

Images 5 days after diagnosing the ocular involvement in the woman with disseminated candidiasis. A – Right eye retinography: multiple, small, round, yellow-white lesions with indistinct borders limited to the posterior pole, one of them in the parafoveal region (arrows). Equatorial Roth spot (white asterisk). B – Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography of the right eye: mild vitritis (yellow arrow) and parafoveal chorioretinal lesion which does not affect the outer retina (red asterisk). C – Left eye retinography: multiple, small, round, yellow-white lesions with indistinct borders in the posterior pole and equatorial retina (arrows). Roth spot hemorrhage (white asterisk). D – Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography of the left eye: mild vitritis (yellow arrow) and preserved foveal profile.

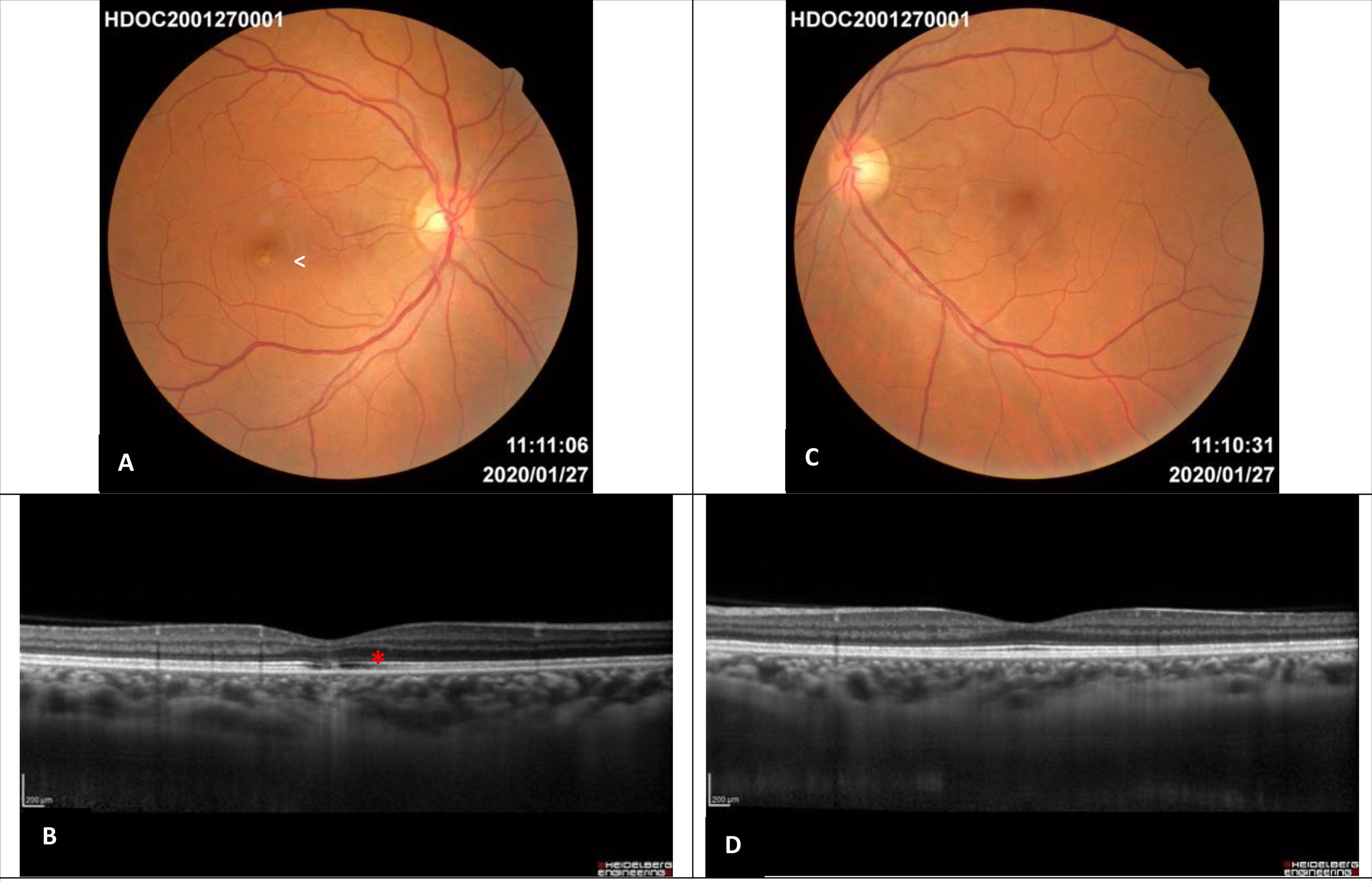

Two months after the diagnosis all lesions had resolved with the exception of a well delimitated focal white-yellow parafoveal lesion in the right eye. One year after the diagnosis the funduscopy showed no anomalies except for the persistence of a white focal parafoveal scar in the right eye. This lesion was visible in SD-OCT as a disruption in the outer retina layers (external limiting membrane, ellipsoid and interdigitation zone), without changing the retinal pigment epithelium integrity (Fig. 2).

Images one year after diagnosis. A – Right eye retinography: residual white focal parafoveal scar (white arrow), complete disappearance of the lesions. B –Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of the right eye: subfoveal disruption in the external limiting membrane, ellipsoid zone and interdigitation zone with retinal pigment epithelium integrity (red asterisk). C – Left eye retinography: normal. D – Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of the left eye: normal.

Ocular candidiasis (OC) occurs in patients with known risk factors: a history of diabetes mellitus, indwelling vascular catheters, broad spectrum antimicrobials, gastrointestinal surgery, intravenous drug addiction, haematologic malignancy and immunosuppression.2,3,5,6,8,14 Our patient had multiple risk factors for IC development: central venous catheter, prior gastrointestinal surgery and broad spectrum antibiotic therapy. Echinocandins (caspofungin, micafungin and anidulafungin) and azole compounds (fluconazole, voriconazole) are the antifungal drugs for treating candidemia rather than amphotericin B as they have less adverse effects.3 Echinocandins are the first-line empirical therapy both in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients with IC.10 However, in the case of patients who are clinically stable and suffer a Candida infection susceptible to fluconazole (C. glabrata and C. krusei), this antifungal agent can be the first-line treatment.4

Therapeutic guidelines4,6,10 recommend systemic antifungal therapy together with frequent ophthalmic examinations in endogenous Candida chorioretinitis with mild vitritis. Nevertheless, echinocandins are not the first-line therapy in cases with ocular involvement.7 The eye is a protected environment due to the blood-retinal barrier, which prevents the intraocular penetration of multiple drugs. Echinocandins (caspofungin, micafungin and anidulafungin), with a molecular weight over 1000Da, have difficulties breaking through the ocular barrier, unlike other antifungals like azole compounds (fluconazole and voriconazole), with a molecular weight under 400Da.

Pharmacokinetic experimental studies in neutropenic rabbits with OC secondary to IC have shown that penetration of the anidulafungin into the vitreous humor is dose-dependent and ranges from undetectable to 0.184g/ml. Therapeutic intravitreal concentrations can only be achieved with much higher systemic doses than those usually employed in clinical practice.7,9,11 On the other hand, regular azole compound doses used in IC do achieve therapeutic intraocular concentrations to inhibit the growth of C. albicans.1,12,15 For this reason, we decided to change the antifungal systemic therapy in our patient.

Current clinical guidelines of the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC), recommend a dilated fundus examination in all patients with positive fungal blood cultures, whether or not they have visual symptoms.4,10,16 However, recent studies show low endophthalmitis incidence rates (1,6%)3,10,13 and postulate that indiscriminate screening does not provide significant improvement in the follow up of these patients.3,5 In fact, early systemic antifungal therapy with drugs with a good vitreous penetration is thought to be enough to resolve the chorioretinitis in its initial phases, and to avoid progression to the symptomatic phase of Candida endophthalmitis.3,10,13

Based on current evidence and on our own experience, we believe that a routinary funduscopy under pharmacologic dilation of the pupil is not necessary in patients with candidemia without visual symptoms in which prompt antifungal treatment has been established. We do believe it should be performed in paediatric patients and those with an altered level of consciousness, (i.e. patients in an intensive care unit), who will be unable to report early visual symptoms, as well as patients who are being treated with echinocandins in monotherapy due to its low intraocular penetration.

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.