Sports-related sudden death is an unusual event. It causes a great social impact. The incidence has been heterogeneous, and coronary artery disease is the most frequent cause in subjects over 35 years-old. Cardiomyopathies and congenital coronary artery anomalies are more usual in younger people. The performing of a medicolegal autopsy is necessary in most cases. A detailed death scene investigation has to be performed, along with a full autopsy with toxicological and histopathological investigation. If the autopsy is negative, genetic studies are requested to rule out disease that may cause cardiac arrhythmias. Sudden deaths in custody, including those occurring in a restraint and containment context, have a special interest in Forensic Medicine, for the multifactorial causes as for the circumstances in which they occurred, as well the social media and medicolegal repercussions. This article presents a review, using a practical approach, for the forensic physician.

La muerte súbita del deportista es un acontecimiento infrecuente, pero causa un impacto tremendo en la comunidad. Su incidencia es muy variable, siendo la cardiopatía coronaria la causa más frecuente en sujetos mayores de 35 años. En los jóvenes las más habituales son las miocardiopatías y la anomalía congénita de las arterias coronarias. En muchos casos se realiza la autopsia judicial. Se practicará el levantamiento de cadáver y una autopsia detallada, solicitando análisis toxicológicos e histopatológicos. Si la autopsia es negativa, se solicitarán análisis genéticos para descartar enfermedades que pueden causar arritmias cardíacas. Las muertes súbitas en custodia, incluyendo las que ocurren en el contexto de la reducción y contención, tienen un especial interés en medicina forense tanto por la pluralidad de causas intervinientes como por las circunstancias en que se producen, así como la repercusión mediática y médico-legal que suponen. Este artículo realiza una revisión desde un enfoque pragmático para el médico forense.

In this paper, we are going to review two types of sudden death which we call sudden death in special circumstances. First, we will address sudden death in sport, which is a rare occurrence but is a situation that is normally tragic for the community, because it is difficult to understand how someone who is generally young, normally healthy and who practises sport can die in such an unexpected way, and in such a short space of time. Then we will deal with sudden deaths in custody, which are of great interest in forensic medicine due to their wide range of causes, as well as due to the circumstances in which they occur. Sudden deaths can also attract a great deal of media attention and, therefore, have important legal and medico-legal implications.

Sudden death in sportWe can define sudden death as a natural, unexpected death, which occurs within the first hour from the onset of symptoms in a subject who was previously healthy or who had a disease that was clinically controlled.1 Sports-related sudden death (SrSD) is an unexpected, tragic situation which has devastating effects on families, on sports teams, where applicable, and on the public in general because it occurs in subjects who are believed to be in a good state of health because they are active. Sudden death is considered to be related to sport when it occurs while doing sport or in the following hour.2 As is well known, doing moderate exercise is an established indication for the treatment and prevention of the development of cardiovascular diseases. Doing sport is therefore recommended for the general population.3 However, when exercise is carried out vigorously, it has been shown that this may increase the risk of sudden death during or a short time after exercise, especially in patients with pre-existing heart disease.4,5

In this study, we will carry out a review of the incidence, causes of death and conduct to follow in the event of sudden death in subjects who were taking part in a sporting activity.

IncidenceThe incidence of SrSD is low and, as occurs in the general population, its frequency varies notably as it depends on the definition used, the age of the athlete, the population studied and the possible loss of cases due to the fact that it is not compulsory to report them.2 In general, incidence increases with age and is more common in males and in black athletes.6 The sports in which sudden death is most likely to occur are basketball, football and cycling, although this varies according to the series and the country.2 Furthermore, in general no sport is more dangerous than any other. The risk is determined by the existence of a condition capable of causing SrSD and the intensity of the effort. Therefore, the frequency of SrSD is defined by the number of participants in each sporting activity.7

The incidence varies according to the series, but in general it ranges between 0.16 and 3.76 cases/100,000 population/year.8 Of the different papers published, we would like to highlight the study by Van Camp et al.9 on a national registry in the United States in which the authors estimated a prevalence of SrSD in child and youth athletes of 0.4/100,000 athletes/year. In a study on the prevalence of sudden death due to cardiovascular disease in young competitive athletes in Minnesota aged between 13 and 19 years, Maron et al. demonstrated a prevalence of 0.35/100,000 sports participations and of 0.46/100,000 sports participants/year.10 Another prospective study conducted in the Italian region of Veneto found an SrSD incidence of 2.3 (2.62 in males and 1.07 in females)/100,000 athletes/year, of all causes, and 2.1/100,000 athletes/year of cardiovascular cause.11

Causes of sudden death in sportMost young athletes who suffer a SrSD have an unsuspected structural heart disease, forming the substrate for presenting with a ventricular arrhythmia which may lead to a cardiac arrest.12 Cardiomyopathies are one of the most common causes of sudden death in young athletes, while coronary artery disease is particularly prevalent in individuals aged over 35 years.2,8,13 Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has been found to be the most common cause in more than one third of SrSDs in the USA.13 In cases recorded in the Italian region of Veneto, it was possible to prove arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia as the cause of SrSD in around one quarter of the cases.12,14 Other heart diseases reported as the cause of SrSD are congenital abnormalities of the coronary arteries, myocarditis, idiopathic left ventricular hypertrophy, dilated cardiomyopathy, mitral valve prolapse and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.6 No evidence of a structural heart disease is found in the autopsies of an assessable percentage of young subjects who die from SrSD, indicating that they may have suffered a channelopathy. This is a disease caused by abnormalities in some of the genes which encode for ion channels (sodium, potassium or calcium) or their associated proteins, such as long QT syndrome, short QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome or catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.15 In fact, it is accepted that in 2–42% of the cases studied, according to the SrSD series, a structural heart disease or other causes which justify the death are not found (especially in the youngest subjects).16,17 In these cases, we are dealing with sudden unexplained death,18 and performing post-mortem genetic testing, or the so-called molecular autopsy, is indicated.15,16,19

There are other causes of unexpected death which should always be taken into account in cases of SrSD, such as cardiothoracic injuries, heatstroke, deaths related to drugs or other non-cardiac causes of sudden death, such as aortic disease (e.g. Marfan syndrome), bronchial asthma, a pulmonary embolism or a subarachnoid haemorrhage due to a ruptured brain aneurysm, among other causes.12

Commotio cordis or cardiac concussion is the result of a non-penetrating closed trauma in the chest which causes ventricular fibrillation, and which is not associated with a structural lesion in the sternum, the ribs or the heart.6,20 The exact frequency of commotio cordis while doing sport is unknown, but it may not be a rare cause of SrSD, and more prevalent than some cardiovascular causes.6

Conduct to be followed by the medical examiner in these casesIn these situations, it is most likely that if an SrSD occurs, for example while running a marathon or during another sports competition, and if the death is instant and it has not been possible to resuscitate the person, normally because it is an unexpected death, no doctor signs the death certificate and the duty court has to intervene. In these cases, the visual inspection and removal of the body procedure is carried out by the judicial commission. It is important that the medical examiner carries out a careful review of the scene, determines through eyewitnesses the full details of the circumstances of the death, rules out any type of violence and inspects the body in situ. Subsequently, the cadaver should be transferred to the Forensic Pathology Department of the Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Science corresponding to the area where the body was found.

Given that sudden death, especially in subjects less than 35-years-old, is often the first and last manifestation of a disease, the autopsy is the only way to establish its cause.21 It should therefore always be performed, not only because it is often a legal requirement, as well as a right of the family and the community to know the cause and circumstances of the death, but also due to the possible medical implications for direct family members.21 Around 30–40% of sudden deaths in young subjects can be attributed to an inherited heart condition, many passed on by an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, and this means that first-degree relatives may be carriers or be susceptible to presenting with the disease.21,22

According to the Guidelines issued by the Association for European Cardiovascular Pathology, the role of the autopsy in cases of sudden death is to establish or to consider: 1. If the death is attributable to a heart disease or to other causes of sudden death. 2. The nature of the heart disease, and if the mechanism of death was arrhythmic or mechanical. 3. If the condition causing the sudden death may be inherited, therefore requiring both testing and counselling of the direct family members. 4. The possibility of toxic substances or drug abuse, trauma and other unnatural causes. 5. Ruling out the role of third parties in the death.23

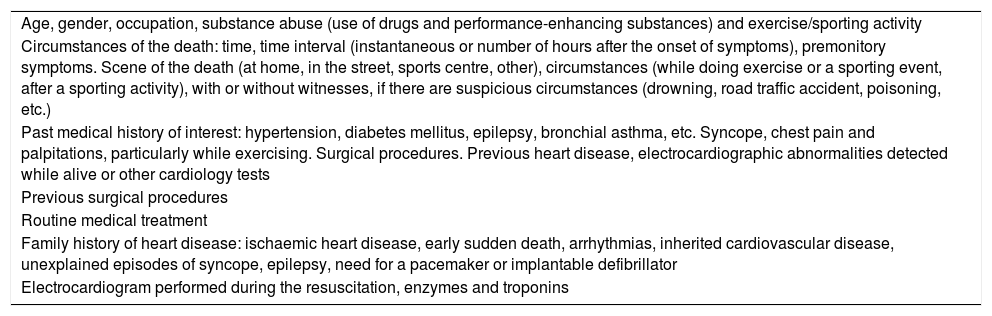

If possible, relevant clinical information should be obtained before the autopsy from the body removal procedure, or subsequently from family members, friends or the deceased's doctor. Table 1 shows the clinical information that should be obtained in these cases.

Relevant clinical information for the autopsy of a sudden death case.

| Age, gender, occupation, substance abuse (use of drugs and performance-enhancing substances) and exercise/sporting activity |

| Circumstances of the death: time, time interval (instantaneous or number of hours after the onset of symptoms), premonitory symptoms. Scene of the death (at home, in the street, sports centre, other), circumstances (while doing exercise or a sporting event, after a sporting activity), with or without witnesses, if there are suspicious circumstances (drowning, road traffic accident, poisoning, etc.) |

| Past medical history of interest: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, bronchial asthma, etc. Syncope, chest pain and palpitations, particularly while exercising. Surgical procedures. Previous heart disease, electrocardiographic abnormalities detected while alive or other cardiology tests |

| Previous surgical procedures |

| Routine medical treatment |

| Family history of heart disease: ischaemic heart disease, early sudden death, arrhythmias, inherited cardiovascular disease, unexplained episodes of syncope, epilepsy, need for a pacemaker or implantable defibrillator |

| Electrocardiogram performed during the resuscitation, enzymes and troponins |

All autopsies should first rule out any type of violent death and then the main extracardiac and cardiac causes of sudden death.21,23 The autopsy procedure should follow “Recommendation No. (99) 3 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on the harmonisation of medico-legal autopsy rules”.24

In the autopsy, a detailed external examination, a complete autopsy with a sequential approximation of the causes of sudden death and exclusion of the non-cardiac causes should be performed, before applying the standard procedure of the macroscopic and microscopic examination of the heart following the published guidelines.21,23,25,26 In some cases, fixing the entire heart in formalin and sending it to a specialised forensic pathology centre is recommended, especially in complex cases, congenital heart diseases and after heart surgery or percutaneous interventions.23 Subsequently, samples (blood and other fluids) should be sent to the forensic toxicology laboratory (requesting toxic drugs, medicinal products and new designer drugs), for clinical chemistry tests where applicable (to rule out deaths from metabolic or allergic disorders: diabetic or alcoholic ketoacidosis, electrolyte disorders or anaphylaxis), for microbiological testing in some cases (in the event of myocarditis, sepsis or endocarditis) and to the molecular genetics laboratory.19,21,23 Finally, a clinical-pathological summary, a formulation of the diagnosis and the conclusions of the autopsy should be drafted.23

Post-mortem genetic testing is clearly indicated in cases of SrSD with negative autopsy (sudden unexplained death) and may be very useful, especially for the diagnosis of inherited cardiovascular diseases: 1. Hypertrophic, dilated, arrhythmogenic, restrictive and non-compaction cardiomyopathy. 2. Channelopathies. 3. Diseases of the aorta: including Marfan syndrome and Loeys-Dietz syndrome.27

In these cases, forming a multidisciplinary team which includes a forensic pathologist, a cardiologist (hospital units for familial heart diseases), a sports medicine specialist and a clinical geneticist would be advised to assess and discuss the case comprehensively, to reach conclusions about the cause and circumstances of the death and to assess the need to recommend genetic screening to the family members of the victim.19,27–30

The creation of the Registro Español de Muerte Súbita del Deporte (Spanish Registry for Sports-related Sudden Death) to include cases of SrSD in young competitive and recreational athletes, and regardless of the outcome (recovered or not recovered from cardiac arrest), also represents an important breakthrough in SrSD.2,28 Finally, prevention through the clinical evaluation of athletes to detect undiagnosed heart diseases, the administration of treatment and the implementation of SrSD prevention strategies is vital.31

Sudden death in custodyThe concept of sudden death in custody, or in prison, includes all situations in which an unexpected death occurs while a subject is under the care and surveillance of an institution or body,32 and covers the following situations:

- a.

Death during restraint and police containment.

- b.

Death of the detained or imprisoned subject, or during escape attempts.

- c.

Deaths of individuals admitted involuntarily to young offender institutions, psychiatric hospitals, internment centres for foreigners or deaths in geriatric institutions due to mechanical restraint.

Due to their circumstances, all of these situations are suspicious deaths and, in accordance with Articles 340 and 343 of the Spanish Law on Criminal Prosecution, are subject to a judicial autopsy.

Once the data obtained from the visual inspection and removal of the body, the medico-legal autopsy and the complementary tests, and all the information available have been studied, the origin of the death will be classified as:

- -

Natural causes, whether they are sudden or unexpected deaths, due to their progression.

- -

Violent causes, whether of accidental, suicidal or homicidal medico-legal aetiology, or undetermined if it was not possible to integrate them into one of the first categories. Due to their social impact and for greater understanding, special relevance should be placed on possible episodes of torture, abuse and deaths derived from hunger strikes.33

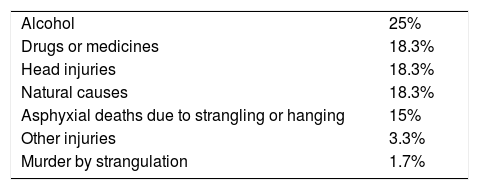

Although establishing comparable figures for this type of death between different countries is very complicated, an approximate ratio of 0.1/100,000 population is estimated34; other studies give disparate figures due to the heterogeneity of the criteria. By way of example, Germany has a ratio of 0.14, Finland of 2.02, Canada of 0.87 and Australia of 0.89/100,000 population.35Table 2 shows the causes of death due to this mechanism in Germany.35

Causes of death during restraint.

| Alcohol | 25% |

| Drugs or medicines | 18.3% |

| Head injuries | 18.3% |

| Natural causes | 18.3% |

| Asphyxial deaths due to strangling or hanging | 15% |

| Other injuries | 3.3% |

| Murder by strangulation | 1.7% |

Source: Heide.35

In Spain, there were 128 deaths in penal institutions in 2014.36 Of these, deaths related to natural causes not attributable to human immunodeficiency virus infection increased to 47.7%. Cardiovascular origin was the predominant cause (49.2%), and half of these were caused by ischaemic heart disease. 19.5% were caused by drugs, 18.8% were suicides, 3.1% were accidental deaths and 1.5% were murders. These figures do not include police restraint deaths or deaths in social-health centres. Regarding deaths in social-health centres, the report from the Spanish Bioethics Committee, dated 7 June 2016, specifies a figure of 40% from permanent mechanical restraints in residential care homes for the elderly. This figure is much higher than in other countries (15% in France, Italy and the USA or 10% in Switzerland, Denmark and Japan),37 with the consequent risk of possible deaths due to mechanical restraint complications.

Possible types of death and situationsNatural deathsDeaths in custody can be caused by previous diseases as well as outside the prison setting, and may be the cause of complaints due to possible negligence. However, the deaths that are of most interest in the forensic field are sudden deaths, particularly of cardiac, pulmonary and cerebral causes (including ischaemic heart disease, cardiomyopathies, pulmonary thromboembolism, worsening of asthma attacks or ruptured aneurysms) in a stressful context.

Regarding excited delirium, cases of death due to acute stress have been reported.38 This is a type of natural death in which the main influencing factor is not the previous condition, but, rather, extreme anxiety factors. In some cases, the only medical history is of a psychiatric nature, such as manic states or chronic stress, presenting a behavioural state similar to excited delirium without the involvement of any drugs, but with the same fatal mechanism. These situations can be accompanied by lesions characteristic of restraint, but without them being significant enough to be the cause of death.38

Violent deathsDrugs. This type of death can occur both during the restraint of the subject and in subsequent phases. The drugs involved are normally alcohol, cocaine, opiates, amphetamine derivatives, hallucinogens and psychotropic drugs, either taken individually or in combination. One of the mechanisms to rule out is the rupture of one of the devices in the so-called ‘body packer’ or drug courier.

Excited delirium. This is the cause of paradigmatic death in the following contexts. It occurs in subjects with extremely violent behaviour who put up extreme and irrational resistance to police restraint. These deaths are due to a combination of the physiological effects of stress and the action of drugs, mainly cocaine, amphetamines and, occasionally, hallucinogens. Once restrained, the subject calms down and, a short time later, dies either at the scene, during transportation or at the police station.39

In addition to the context explained, situations of hyperthermia, extraordinary force, resistance, hyperactivity, incoherence and lack of pain response are prevalent. It is estimated that approximately 10% of cases of excited delirium result in death.40,41

Although the exact mechanism is unknown, it is related to an intense release of catecholamines, both due to stress and stimulant drugs, with the consequent increase in heart and respiratory rate, hypertension, greater myocardial oxygen consumption, hyperkalaemia and increase in the number of muscle enzymes due to rhabdomyolysis which, along with inhibiting the reuptake of catecholamines produced by the drugs, contributes to coronary vasospasm. Once restrained, the subject suddenly reduces his/her physical activity, but the release of catecholamines persists for 1–3min, which, combined with subsequent hypokalaemia and coronary vasospasm, leaves the detainee very vulnerable to ischaemia and possible cardiac arrhythmias.39

The studies by Ruttenber point to the involvement of dopamine.40 Chronic consumers of cocaine have an adaptive response (tolerance) to facilitating the reuptake of dopamine in the neuronal synapses, through a reduction in the dopamine D1-like receptor subtypes, but maintaining levels of D2-like receptor subtypes. Subjects with excited delirium have a reduced number of D2-like receptors, mainly at hypothalamic sites. This vulnerability is possibly the cause of hyperthermia, autonomic dysregulation and psychotic behaviour or excited delirium.40

Restraint by spinal immobilisation. Choke hold. The subject is immobilised through pressure of the forearm on the front part of the neck, causing the airway to be compromised. The hold can also be performed using a rigid, long object such as a truncheon.39

Carotid sleeper hold. The subject is immobilised from behind with the elbow flexed on the tracheal region, exercising pressure bilaterally on the carotid arteries and jugular veins, which reduces the blood supply to the brain resulting in ischaemia and cerebral hypoxia.42

Shoulder pin restraint. Variation of the carotid sleeper hold with a lateral approach in which the subject's own shoulder is lodged, reducing abduction to 180 degrees, at which point the forearm is pressed on the cervical contralateral area.43

Stimulation of the carotid sinus or vagal inhibition. This mechanism has been proposed as a possible cause of death via a reflex discharge of the vagus nerve, with resulting bradycardia and death of the subject without sufficient mechanical pressure to obstruct circulation or the airway.43

Positional asphyxia. The subject is lying in the decubitus prone position with his/her hands tied behind his/her back and the lower extremities bent forcibly with the heels very close to the hands (Hogtie prone).44 A less restrictive variation in terms of ventilation, and therefore with less risk of death, occurs in the same position but with the legs bent only at 90 degrees (Hobble prone). Both can cause claudication of the ventilatory mechanisms.44

They are not common restraint practices of police forces, but occasionally immobilisation can occur on sloped ground with the upper part of the body receiving greater flow than the rest of the body for an excessive length of time.

In patients admitted to psychiatric facilities or residential care homes for the elderly, straitjackets or thoracoabdominal mechanical restraints may result in similar positions to those described above due to the subject's movements, or they may find themselves suspended by the restraint, which can cause the subject's death.45 All these situations of ventilatory restriction are exacerbated by previous respiratory diseases, alcohol intoxication or drugs which reduce the level of awareness.

Drowning. Boarding small boats for illegal immigration, or in the case of boats used to transport drugs.

Use of non-blunt weapons. Firearms: with normal bullets in which the aim will be injury from a typical firearm, or through the use of soft bullets, such as rubber or foam pellets, which may cause commotio cordis with subsequent arrhythmia due to direct impact in the precordial region or due to direct injury in other sensitive areas. This may cause death due to vagal inhibition in predisposed subjects, as well as other lesions.

Stun guns: these are instruments which cause an electric shock of considerable voltage (50,000–250,000V).32 Lesions associated with their use, such as superficial burns when the electric shock passes through the skin, musculoskeletal lesions due to intense muscle contraction, head lesions from induced falls and possible triggering of epileptic seizures, have been reported.46 Also, by causing an involuntary skeletal muscle contraction, depending on the intensity, the duration of the shock and the vulnerability of the subject to this shock, it may occasionally lead to death as a result of alterations in the ventilatory mechanism due to its effects on the thoracic muscles, the induction of status epilepticus or fatal arrhythmias.46

Different aerosols or sprays, such as pepper or other irritants: the spraying of irritant substances does not usually result in death. However, in some circumstances they may generate an acute asthma attack or glottic oedema in subjects sensitive or allergic to the irritant. At the same time, they may cause a spasmodic cough, temporary reduction in vision and cause death indirectly due to states of panic and uncontrolled flight with sudden falls, jumping from a height or being run over.

Injuries. Of a varied nature, whether they are of an accidental nature during the flight, such as falls, jumping from a height or being run over, or of a voluntary nature, self-inflicted, or inflicted by another person as a means to reducing the subject's resistance and facilitate the restraint. Defence weapons, such as truncheons or any blunt object, are also included. From the aforementioned lesions, those caused by a standard restraint action that are not significantly important in the triggering of the death must be differentiated.

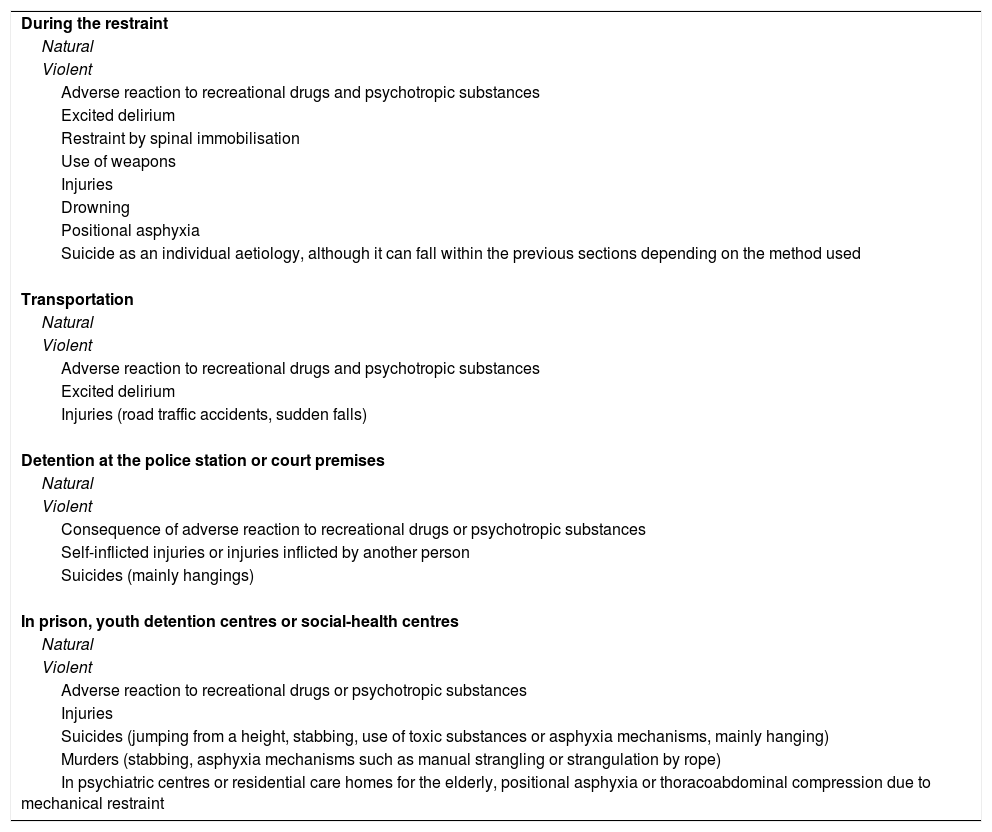

Suicide. In any of its multiple varieties, whether from stabbing, jumping from a height, hanging or any other mechanism; the prison population is considered potentially at risk, reaching figures of 18.8% in penal institutions.36Table 3 summarises the different types and causes of death in custody.

Possible types and causes of death during the different phases of restraint or custody.

| During the restraint |

| Natural |

| Violent |

| Adverse reaction to recreational drugs and psychotropic substances |

| Excited delirium |

| Restraint by spinal immobilisation |

| Use of weapons |

| Injuries |

| Drowning |

| Positional asphyxia |

| Suicide as an individual aetiology, although it can fall within the previous sections depending on the method used |

| Transportation |

| Natural |

| Violent |

| Adverse reaction to recreational drugs and psychotropic substances |

| Excited delirium |

| Injuries (road traffic accidents, sudden falls) |

| Detention at the police station or court premises |

| Natural |

| Violent |

| Consequence of adverse reaction to recreational drugs or psychotropic substances |

| Self-inflicted injuries or injuries inflicted by another person |

| Suicides (mainly hangings) |

| In prison, youth detention centres or social-health centres |

| Natural |

| Violent |

| Adverse reaction to recreational drugs or psychotropic substances |

| Injuries |

| Suicides (jumping from a height, stabbing, use of toxic substances or asphyxia mechanisms, mainly hanging) |

| Murders (stabbing, asphyxia mechanisms such as manual strangling or strangulation by rope) |

| In psychiatric centres or residential care homes for the elderly, positional asphyxia or thoracoabdominal compression due to mechanical restraint |

The primary aim of the medico-legal investigation is to find out whether a death was natural or violent and, in the latter case, its aetiology (accidental, suicide or murder), as well as all associated circumstances.

We will follow the different national and international regulations, such as the Minnesota Protocol,47 the Istanbul Protocol48 and Recommendation No. (99) 3 on the harmonisation of medico-legal autopsy rules,24 as well as the protocols of the different Legal Medicine and Forensic Science Institutes in accordance with the aforementioned legislation.49

Procedure for visual inspection and removal of the bodyA comprehensive on-site examination of the body will be performed, gathering all the possible evidence and data on the facts, the most accurate chronology possible, declarations from witnesses and involved parties, circumstances and relative positions, and whether resuscitation manoeuvres have been carried out. The type and mechanism of restraint, degree of resistance and aggressiveness, as well as the prior history of the deceased, including use of medicines and drugs, doses and routes of administration, will be reported.

Macroscopic autopsyIt is recommended that this autopsy be performed by two medical examiners, and that a thorough external examination is carried out, using ultraviolet light, to view any remains of powdered or biological material, or lesions which cannot be seen macroscopically.49

Electric burns, lesions from bruising or pressure, mainly on the cervical area, and erosions or small ecchymoses which provide evidence of the positions of the deceased during the restraint should be looked for.

The subcutaneous dissection of tissues, including those of the facial and cervical regions, should be carried out using techniques such as “peel-off”.49 All of this must be accompanied by visual evidence (photographs/videos) of the initial state of the cadaver and all phases of the autopsy, as the absence of lesions is just as important as finding them.

There should be a full internal examination, including the airways, hyoid bone, thyroid cartilage, carotid sinuses and spinal cord, as well as the testicular region.

Complementary tests49A full radiological study of the body is recommended before performing the autopsy. Samples of urine, blood, bile and vitreous humour should be collected, an eye, nose and mouth swab should be taken, and samples from the liver, kidney, brain and lung should be collected for the toxicology study, as well as from the stomach and its contents.

Samples of vitreous humour, blood and urine must be collected for biochemical analyses. Subungual samples should be collected for biological testing and a blood sample taken directly from the deceased for the possible carrying out of DNA tests. These should be compared with the other biological fluids from the scene or from alleged aggressors.

Regarding histopathological analyses, a study of the main organs, such as the brain, including the pituitary gland, hyoid bone and neck cartilage, lungs, heart, liver, spleen, pancreas, kidneys and adrenal glands, aorta and carotid arteries, and all appropriate tissues, in accordance with the autopsy findings, should be carried out.

Finally, we should mention that the sudden deaths of young males after being taken into police custody are often complex cases, which are difficult to assess and are sometimes multifactorial.50

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pujol-Robinat A, Salas-Guerrero M. Muerte súbita cardíaca en circunstancias especiales. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2018;44:38–45.