Night work has been discussed in occupational health because of the potential risk to the worker and its impact on accident rates.

While any worker can perform legal exceptions and preventive demands do exist, highlighting those derived from the health surveillance, mandatory in this case, and usually with annual periodicity.

References in night work in Spain are Directive 2003/88/EC, the Workers’ Statute, the Act on Prevention of Occupational Risks and the Royal Decree for Prevention Services.

In the scientific literature (Pubmed), studies relating night work to various health problems, including neoplasia, are found but without sufficient scientific evidence.

The legal debate (Westlaw Insignis) is focused on exceptional situations: minors, pregnant or breastfeeding women and particularly sensitive workers.

A greater understanding of this issue will facilitate the prevention of damages and prevent medicolegal problems.

El trabajo nocturno ha sido objeto de estudio en Salud Laboral por potencial riesgo para el trabajador y su repercusión en la accidentalidad.

Aunque a priori cualquier trabajador puede desempeñarlo, existen excepciones legales y exigencias preventivas, entre las que destacan las derivadas de la vigilancia de la salud, en este caso obligatoria y, habitualmente, con periodicidad anual.

Es normativa de referencia en trabajo nocturno la Directiva 2003/88/CE, el Estatuto de los Trabajadores, la Ley de Prevención de Riesgos Laborales y el Real Decreto de los Servicios de Prevención.

La revisión realizada de la bibliografía científica (Pubmed) relaciona el trabajo nocturno con diversos problemas de salud, incluidos procesos neoplásicos.

La revisión realizada de la jurisprudencia española (Westlaw Insignis) se centra en la conflictividad generada por trabajo nocturno en: menores, mujeres embarazadas o en período de lactancia, y trabajadores especialmente sensibles.

Un mayor conocimiento de este tema facilitará la prevención y disminuirá la conflictividad médico-legal.

Labour is a right of all citizens, set out in the Spanish Constitution (Article 35), and provides that the law must regulate a workers’ statute.

In terms of prevention, Article 2 of Act 31/1995 on Prevention of Occupational Risks (APOR) establishes the regulations for promoting the safety and health of workers through the application of measures and the development of activities necessary for the prevention of risks arising from work.1

In occupational health, night work is a specific preventive objective because of its impact on the health of workers, especially those who are more sensitive.

In Spain, the National Institute of Safety and Hygiene at Work has published different technical notes on prevention (TNP) on this subject: TNP 455, organisational aspects of shift work and night work2; TNP 260, medical and pathological effects of alternating shifts: shift work sleep disorder3; TNP 310, nutritional conditions for such workers4; and TNP 502, prevention of effects on workers’ physical and psychological health or social interaction.5

Planning the productive activity at a company involves organising working times based on the activity developed, needs and requirements of production and requirements of the market for which it is intended. This planning must comply with what is agreed in collective agreements or labour contracts, without exceeding 40h a week.6 Work in irregular shifts (rotating, night or prolonged) is increasing due to economic and production-related reasons, or social reasons, and it is of special interest in occupational health.

Types of working dayWorking time has a direct impact on daily life and the health and well-being of workers. One of the main causes of this effect is the difficulty in adjusting to changes in circadian and social rhythms and poor organisation of shifts.

It is important to know the different types of distribution of working times to take preventive action on the potential repercussions that, especially with night work and shift work, can affect workers’ health.

From a regulatory point of view, working time can be grouped into7:

- (1)

Continuous working day: work activity that continues uninterrupted, with periods of rest, following the preventive recommendations in this regard in Act 31/95 (APOR).

- (2)

Split working day: daily working time is divided into 2 parts, with a break for a meal. The minimum duration of this break is not specifically regulated, and it is assumed that it must be greater than the minimum ones for the continuous working day, to allow for one of the main meals of the day.

When the working day is changed at a company, this involves a substantial change in working conditions and it cannot be adopted unilaterally by the employer, according to the provisions of Article 41 of RD 1/1995, consolidated text of the Workers’ Statute8 (WS).

- (3)

Intensive working day: the daily working time is lower than usual, but runs continuously. This is regulated by collective bargaining (for the summer months or holiday periods).

- (4)

Fixed schedule: work is adjusted to predetermined and unchanging time modules. The workers remain at their post from the beginning of the day until the end, simultaneously.

- (5)

Flexible schedule: each worker may establish the start and end of his/her working day, within a time frame with the rest of the employees. There need not be complete simultaneity amongst the different workers of the company. This is only feasible in areas or sectors where the production system does not require the simultaneous presence of workers. It lacks a legal norm and is regulated through collective and company agreements.

- (6)

Shift work: the legal definition of shift work is found in Article 36(3) of the WS: “any form of organising teamwork according to which workers successively occupy the same posts, according to a specific rhythm, either continuous or discontinuous, meaning that workers need to render their services at different times over a given period of days or weeks”. This includes 3 types of shift work:

- (a)

Continuous shift work: activity maintained every day of the week and 24h a day, uninterrupted. This involves 3 shifts a day, including night work.

- (b)

Discontinuous shift work: work interrupted normally at night and at the weekend. This involves 2 shifts: morning and afternoon.

- (c)

Semi-continuous shift work: activity carried out 24h a day, interrupted by rest on Sundays and holidays. This involves 3 shifts on weekdays (morning, afternoon and night).

- (a)

Shift work involves the provision of services at different times over a given period of days and weeks, and involves rotating workers’ working times.

There are differences between the Spanish system and systems across the international community: shift work is “any employment system in which the schedule departs from the traditional hours of 9:00–17:00 (approx.), which includes evening and night schedules, rotating shifts, split shifts, on-call or occasional shifts, 24-h shifts, irregular schedules (e.g. flight personnel) and other non-daytime schedules”.

The legal provisions on shift work are focused on:

- (a)

Specific assumptions on the organisation of shift work.

- (b)

Specific daily and weekly rest periods.

- (c)

Safety and hygiene, in view of the greater hardship.

- (d)

Fixed and rotating shifts: when continuous productive processes are required 24h a day. In these cases the organisation of the work must take into account shift rotations and that no worker may work at night for more than 2 consecutive weeks, unless its a voluntary assignment (Art. 36(3)(2) of WS).

Spanish labour legislation establishes the concepts of night work and night workers.

Concept of night workNight work: takes place between ten at night and six in the morning (Art. 36(1) of WS). This period may be extended by agreement, but it must never be shortened. In specific groups, such as the merchant navy, night work is considered work that is done between ten at night and seven in the morning (RD 1561/1995, Additional Provision 4(a)).9

Directive 2003/88/EC10 lays down the minimum health and safety requirements for organising working time as regards: daily rest periods, breaks, weekly rest periods, maximum weekly working hours, annual leave and certain aspects of night work, shift work and working rhythms. This follows Directives 93/104/EC and 2000/34/EC. It also contains important regulations for health protection applicable to shift-work schedules, night shift work and dangerous activities.

The working day for night workers may not exceed 8h/day on average, in a 15-day reference period, able to be extended to a maximum of 4 months (up to 6 by collective agreement) for a higher hourly elasticity, but maintaining the maximum 8h/day on average, and these workers may not perform overtime (Art. 36(3) of WS).

There are exceptional situations in which night workers’ working hours may be extended (Art. 32 of RD 1561/1995):

- (a)

Assumptions of extensions of the working day provided for in chapter ii of RD 1561/1995:

- (1)

Security and maintenance workers, police and non-railway security guards.

- (2)

Agricultural work.

- (3)

Trade and hospitality.

- (4)

Transport and work at sea.

- (5)

Shift work.

- (6)

Starting and closing the works of others.

- (7)

Work in special conditions of isolation or distance.

- (8)

Work in activities with split working hours.

- (1)

- (b)

When necessary to prevent and repair casualties or other extraordinary and urgent damage.

- (c)

In shift work (which partly incorporates night work), in case of irregularities in shift relief due to causes not attributable to the company.

In specific professions, hours worked that exceed the maximum limits may be paid at a higher rate, through overtime pay or by extending the calculation period for the 15 basic days to ensure an adequate calculation. If overtime is worked within the exceptions, it may be compensated financially or through rest periods.

Night workers may only work overtime when they fall within the 3 exceptional cases mentioned above, and even in these cases the work schedule must be reduced in order not to exceed the reference average.

Concept of night workerNight worker: one who does at least 3h of his/her work within the established limits, or when according to the annual computation it is observed that at least one-third of the working day is spent between them (Art. 36(1)(3) of WS). What is important here is not the actual record at the end of the year of the number of hours worked at night by each worker, but rather the scheduling of work established by the company and whether in this scheduling at least one-third of the working day is expected to be carried out at night time.11

Not all workers who work at night are considered night workers, but whenever a company uses night work, it must inform the labour authority in its Autonomous Community (Labour and Social Security Inspectorate) (Art. 36(1) of WS), to monitor compliance with legal norms, verify the regularity of night work adjusted to frequency standards and periods, and take sanctioning prerogatives if non-compliance with the regulations is detected (Art. 6(5) of LISOS–Act on Infractions and Sanctions in the Social Order).12

Limitations on night workA priori, every worker may perform work at night, except for the exceptions regulated by law and must receive an economic compensation that establishes differences according to the severity of the schedule.

In general, the following are considered to be specially protected groups with regard to night work: people under 18 (Art. 6(2) of WS), pregnant women and especially sensitive workers.

When workplace hazards are detected that may affect the safety and health of a pregnant woman or which may have an impact on the pregnancy or breast-feeding, the employer must take the necessary measures to prevent exposure to the hazard(s) by adjusting the working conditions or times, and if this is not possible, the woman must not perform night work (Art. 26(1) of APOR).

If a worker is considered particularly sensitive (Art. 25 of APOR) because of the effects of the nighttime hours on his/her health, s/he must be protected by a protocol established by each company for these purposes.

Regulation of economic compensation for night workThis is established through collective bargaining for a specific remuneration, i.e. the night shift differential, such as a percentage over the base salary. It can also be a fixed amount, but subject to withholding and with contribution to social security.

There are situations in which an additional amount will not be paid for performing night work (Art. 36(2) of WS):

- (a)

When a night worker moves to a daytime schedule.

- (b)

When it has been agreed to compensate for night work through rest periods.

- (c)

Work qualified as night work by its nature. Activities that must be performed at night (bakery, surveillance, cleaning, etc.).13 The salary already establishes the compensation in regard to this type of night work, and it is integrated into the general concepts of workers’ salaries. It is usually indicated in a collective agreement. When a work is done in shifts of morning, afternoon and night, this indicates that it is not nighttime activity in nature.14

Spanish jurisprudence has been adjusting the concept of economic compensation for night work and requires that nighttime working hours be specifically remunerated, even if the person who works these hours qualifies as a day worker.15 The hours of night work (from 10 at night to 6 in the morning) must be paid at the night-shift differential that is established in the collective agreement, regardless of number or of the start or end times to the working day. A collective agreement may not introduce additional conditions in order to be entitled to receive the night-shift differential.16

Specific considerations in health monitoring of night workersArticle 36(4) of the WS establishes the obligation to provide a prior medical examination when assigning tasks in night work, and later at regular intervals, to workers who have a night job, under the terms established in the specific regulations in the matter. This would constitute one of the exceptions to voluntary health monitoring by workers. This is also established in Article 37(3)(b)(1) of the Regulation for Prevention Services.17

Mandatory health checks under the specific risk-protection rules are aimed at determining the health status of workers before they are assigned to a job, in order to determine whether their physical conditions are compatible with the tasks or whether the exposure to this hazard is contraindicated for said workers. This is the preventive principle that applies in the case of night workers.

If changes in the health of an employee linked to night work are detected, they must be transferred to a day shift for which they are professionally prepared, even if they do not belong to the same professional category, entering into the protection established for especially sensitive workers (Art. 25 of APOR).

Scientific publications on undesirable effects on the health of night workersThe scientific literature has dealt with this topic extensively, contributing a large number of publications, some of which incorporate preventive initiatives.

The publication by Ruggiero and Redeker18 in 2014 conducts a detailed review of the scientific literature from 13 relevant studies of small samples and varied designs on the improvements achieved by planned naps for night workers. Most researchers found that after these nap periods there were short periods of sleep inertia, but in most workers there was a decrease in drowsiness and better performance related to improved sleep. None of the studies examined the effects of napping on safety in the workplace, suggesting the need to probe deeper into this aspect.

Other authors have analysed in a more concrete way the health risks of night work in acute and chronic diseases that stem from such work. Some of these reviews form part of related studies that have been maintained over time, such as the one presented in 1977 at the Fourth International Symposium sponsored by the Permanent Commission and International Association on Occupational Health,19 with particular reference to the effect of altering chronobiology in specific diseases such as cancer; or the one published in 2014 by Sorokin and Frolova,20 in which the authors analysed the risk to health in both acute and chronic conditions in night shift workers, calculating the annual increases in average risk for various diseases and concluding on concrete specifications regarding the degree of risk involved in night work.

Multiple studies relate night work to specific diseases, such as sleep disorders, when shifts are not adjusted to workers’ individual chronotypes and ages21; diabetes, by promoting insulin resistance and changing cellular oxidative stress22; metabolic syndrome, with increased risk as a function of the work cycle23; and even with a greater number of processes of musculoskeletal disease or a longer duration of these processes.24

Currently, the largest number of studies focuses on the relationship between night work and cancer: colorectal cancer,25 especially in women26; breast cancer, being discussed at this time and involving multiple factors associated with the risk inherent in night work,27 although the scientific debate revolves around the role of melatonin as a breast cancer inhibitor28 and in ovarian cancer, although in this type of cancer it has not been possible to establish a significant relation that relates it to modifications in melatonin29; prostate cancer30; lung cancer, assuming in these cases that increased smoking is the main factor in these workers.31 The evidence of the various studies is still limited and raises the need for future studies that go deeper into this topic.32

One of the most recent studies is “Working Women and Breast Cancer: State of the Evidence”, published in August 2015 by the American NGO Breast Cancer Fund, which conducted an exhaustive review of the existing scientific literature on the relationship between breast cancer and workplace exposure and refers to occupations for which there is scientific consensus of an association with an increased risk of breast cancer (nurses, teachers, librarians, lawyers, radiological and laboratory technicians, industrial workers and workers exposed to chemical solvents).33

Although the studies are not conclusive as regards the effect on people's health and the alteration of their biological cycles due to changes in schedules or shifts of work,33 in specific groups, like nurses, the risk of their health being affected tends to increase with age,34 with a higher number of errors in their work.35 However, a higher number of accidents have been detected in younger, inexperienced night shift workers in this sector.36

The debate on this subject remains open, and some authors question whether there is a benefit in working days of 8 or 12h and argue in this regard that it may be more appropriate to conceptualise the organisation of working time in terms of an “ecosystem” that deal with risks in a global way, as opposed to a single dimension, as is currently the case.37

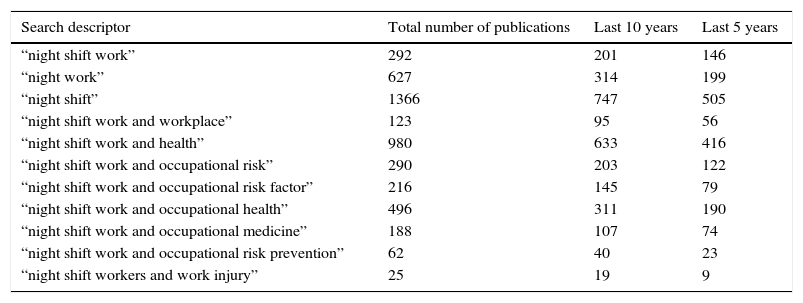

A brief search of Pubmed using the most common descriptors for this subject highlights the work done in the past 5 years, especially with the generic concept of night shift work and its effects on health and the concern in Occupational Health. However, publications on prevention, risk of work-related accidents or occupational risks, which are important in occupational health and occupational medicine (Table 1), are much less common.

Bibliographic review of night work and associated descriptors.

| Search descriptor | Total number of publications | Last 10 years | Last 5 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| “night shift work” | 292 | 201 | 146 |

| “night work” | 627 | 314 | 199 |

| “night shift” | 1366 | 747 | 505 |

| “night shift work and workplace” | 123 | 95 | 56 |

| “night shift work and health” | 980 | 633 | 416 |

| “night shift work and occupational risk” | 290 | 203 | 122 |

| “night shift work and occupational risk factor” | 216 | 145 | 79 |

| “night shift work and occupational health” | 496 | 311 | 190 |

| “night shift work and occupational medicine” | 188 | 107 | 74 |

| “night shift work and occupational risk prevention” | 62 | 40 | 23 |

| “night shift workers and work injury” | 25 | 19 | 9 |

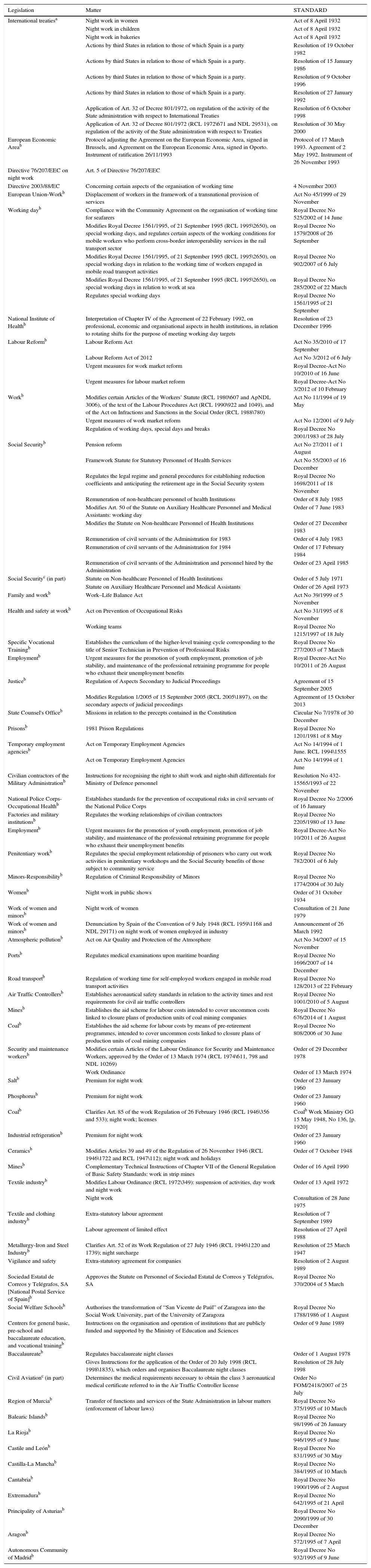

Reviewing the regional, national and international legislation on this issue shows an abundance of standards (116), and most of them are still fully or partially applicable (Table 2).

Spanish legislation on night work.

| Legislation | Matter | STANDARD |

|---|---|---|

| International treatiesa | Night work in women | Act of 8 April 1932 |

| Night work in children | Act of 8 April 1932 | |

| Night work in bakeries | Act of 8 April 1932 | |

| Actions by third States in relation to those of which Spain is a party | Resolution of 19 October 1982 | |

| Actions by third States in relation to those of which Spain is a party. | Resolution of 15 January 1986 | |

| Actions by third States in relation to those of which Spain is a party. | Resolution of 9 October 1996 | |

| Actions by third States in relation to those of which Spain is a party. | Resolution of 27 January 1992 | |

| Application of Art. 32 of Decree 801/1972, on regulation of the activity of the State administration with respect to International Treaties | Resolution of 6 October 1998 | |

| Application of Art. 32 of Decree 801/1972 (RCL 1972\671 and NDL 29531), on regulation of the activity of the State administration with respect to Treaties | Resolution of 30 May 2000 | |

| European Economic Areab | Protocol adjusting the Agreement on the European Economic Area, signed in Brussels, and Agreement on the European Economic Area, signed in Oporto. Instrument of ratification 26/11/1993 | Protocol of 17 March 1993. Agreement of 2 May 1992. Instrument of 26 November 1993 |

| Directive 76/207/EEC on night work | Art. 5 of Directive 76/207/EEC | |

| Directive 2003/88/EC | Concerning certain aspects of the organisation of working time | 4 November 2003 |

| European Union-Workb | Displacement of workers in the framework of a transnational provision of services | Act No 45/1999 of 29 November |

| Working dayb | Compliance with the Community Agreement on the organisation of working time for seafarers | Royal Decree No 525/2002 of 14 June |

| Modifies Royal Decree 1561/1995, of 21 September 1995 (RCL 1995\2650), on special working days, and regulates certain aspects of the working conditions for mobile workers who perform cross-border interoperability services in the rail transport sector | Royal Decree No 1579/2008 of 26 September | |

| Modifies Royal Decree 1561/1995, of 21 September 1995 (RCL 1995\2650), on special working days in relation to the working time of workers engaged in mobile road transport activities | Royal Decree No 902/2007 of 6 July | |

| Modifies Royal Decree 1561/1995, of 21 September 1995 (RCL 1995\2650), on special working days in relation to work at sea | Royal Decree No 285/2002 of 22 March | |

| Regulates special working days | Royal Decree No 1561/1995 of 21 September | |

| National Institute of Healthb | Interpretation of Chapter IV of the Agreement of 22 February 1992, on professional, economic and organisational aspects in health institutions, in relation to rotating shifts for the purpose of meeting working day targets | Resolution of 23 December 1996 |

| Labour Reformb | Labour Reform Act | Act No 35/2010 of 17 September |

| Labour Reform Act of 2012 | Act No 3/2012 of 6 July | |

| Urgent measures for work market reform | Royal Decree-Act No 10/2010 of 16 June | |

| Urgent measures for labour market reform | Royal Decree-Act No 3/2012 of 10 February | |

| Workb | Modifies certain Articles of the Workers’ Statute (RCL 1980\607 and ApNDL 3006), of the text of the Labour Procedures Act (RCL 1990\922 and 1049), and of the Act on Infractions and Sanctions in the Social Order (RCL 1988\780) | Act No 11/1994 of 19 May |

| Urgent measures of work market reform | Act No 12/2001 of 9 July | |

| Regulation of working days, special days and breaks | Royal Decree No 2001/1983 of 28 July | |

| Social Securityb | Pension reform | Act No 27/2011 of 1 August |

| Framework Statute for Statutory Personnel of Health Services | Act No 55/2003 of 16 December | |

| Regulates the legal regime and general procedures for establishing reduction coefficients and anticipating the retirement age in the Social Security system | Royal Decree No 1698/2011 of 18 November | |

| Remuneration of non-healthcare personnel of health Institutions | Order of 8 July 1985 | |

| Modifies Art. 50 of the Statute on Auxiliary Healthcare Personnel and Medical Assistants: working day | Order of 7 June 1983 | |

| Modifies the Statute on Non-healthcare Personnel of Health Institutions | Order of 27 December 1983 | |

| Remuneration of civil servants of the Administration for 1983 | Order of 4 July 1983 | |

| Remuneration of civil servants of the Administration for 1984 | Order of 17 February 1984 | |

| Remuneration of civil servants of the Administration and personnel hired by the Administration | Order of 23 April 1985 | |

| Social Securityc (in part) | Statute on Non-healthcare Personnel of Health Institutions | Order of 5 July 1971 |

| Statute on Auxiliary Healthcare Personnel and Medical Assistants | Order of 26 April 1973 | |

| Family and workb | Work–Life Balance Act | Act No 39/1999 of 5 November |

| Health and safety at workb | Act on Prevention of Occupational Risks | Act No 31/1995 of 8 November |

| Working teams | Royal Decree No 1215/1997 of 18 July | |

| Specific Vocational Trainingb | Establishes the curriculum of the higher-level training cycle corresponding to the title of Senior Technician in Prevention of Professional Risks | Royal Decree No 277/2003 of 7 March |

| Employmentb | Urgent measures for the promotion of youth employment, promotion of job stability, and maintenance of the professional retraining programme for people who exhaust their unemployment benefits | Royal Decree-Act No 10/2011 of 26 August |

| Justiceb | Regulation of Aspects Secondary to Judicial Proceedings | Agreement of 15 September 2005 |

| Modifies Regulation 1/2005 of 15 September 2005 (RCL 2005\1897), on the secondary aspects of judicial proceedings | Agreement of 15 October 2013 | |

| State Counsel's Officeb | Missions in relation to the precepts contained in the Constitution | Circular No 7/1978 of 30 December |

| Prisonsb | 1981 Prison Regulations | Royal Decree No 1201/1981 of 8 May |

| Temporary employment agenciesb | Act on Temporary Employment Agencies | Act No 14/1994 of 1 June. RCL 1994\1555 |

| Act on Temporary Employment Agencies | Act No 14/1994 of 1 June | |

| Civilian contractors of the Military Administrationb | Instructions for recognising the right to shift work and night-shift differentials for Ministry of Defence personnel | Resolution No 432-15565/1993 of 22 November |

| National Police Corps-Occupational Healthb | Establishes standards for the prevention of occupational risks in civil servants of the National Police Corps | Royal Decree No 2/2006 of 16 January |

| Factories and military institutionsb | Regulates the working relationships of civilian contractors | Royal Decree No 2205/1980 of 13 June |

| Employmentb | Urgent measures for the promotion of youth employment, promotion of job stability, and maintenance of the professional retraining programme for people who exhaust their unemployment benefits | Royal Decree-Act No 10/2011 of 26 August |

| Penitentiary workb | Regulates the special employment relationship of prisoners who carry out work activities in penitentiary workshops and the Social Security benefits of those subject to community service | Royal Decree No 782/2001 of 6 July |

| Minors-Responsibilityb | Regulation of Criminal Responsibility of Minors | Royal Decree No 1774/2004 of 30 July |

| Womenb | Night work in public shows | Order of 31 October 1934 |

| Work of women and minorsb | Night work of women | Consultation of 21 June 1979 |

| Work of women and minorsb | Denunciation by Spain of the Convention of 9 July 1948 (RCL 1959\1168 and NDL 29171) on night work of women employed in industry | Announcement of 26 March 1992 |

| Atmospheric pollutionb | Act on Air Quality and Protection of the Atmosphere | Act No 34/2007 of 15 November |

| Portsb | Regulates medical examinations upon maritime boarding | Royal Decree No 1696/2007 of 14 December |

| Road transportb | Regulation of working time for self-employed workers engaged in mobile road transport activities | Royal Decree No 128/2013 of 22 February |

| Air Traffic Controllersb | Establishes aeronautical safety standards in relation to the activity times and rest requirements for civil air traffic controllers | Royal Decree No 1001/2010 of 5 August |

| Minesb | Establishes the aid scheme for labour costs intended to cover uncommon costs linked to closure plans of production units of coal mining companies | Royal Decree No 676/2014 of 1 August |

| Coalb | Establishes the aid scheme for labour costs by means of pre-retirement programmes, intended to cover uncommon costs linked to closure plans of production units of coal mining companies | Royal Decree No 808/2006 of 30 June |

| Security and maintenance workersb | Modifies certain Articles of the Labour Ordinance for Security and Maintenance Workers, approved by the Order of 13 March 1974 (RCL 1974\611, 798 and NDL 10269) | Order of 29 December 1978 |

| Work Ordinance | Order of 13 March 1974 | |

| Saltb | Premium for night work | Order of 23 January 1960 |

| Phosphorusb | Premium for night work | Order of 23 January 1960 |

| Coalb | Clarifies Art. 85 of the work Regulation of 26 February 1946 (RCL 1946\356 and 533); night work; licenses | Coalb Work Ministry GG 15 May 1948, No 136, [p. 1920] |

| Industrial refrigerationb | Premium for night work | Order of 23 January 1960 |

| Ceramicsb | Modifies Articles 39 and 49 of the Regulation of 26 November 1946 (RCL 1946\1722 and RCL 1947\112); night work and holidays | Order of 7 October 1948 |

| Minesb | Complementary Technical Instructions of Chapter VII of the General Regulation of Basic Safety Standards: work in strip mines | Order of 16 April 1990 |

| Textile industryb | Modifies Labour Ordinance (RCL 1972\349): suspension of activities, day work and night work | Order of 13 April 1972 |

| Night work | Consultation of 28 June 1975 | |

| Textile and clothing industryb | Extra-statutory labour agreement | Resolution of 7 September 1989 |

| Labour agreement of limited effect | Resolution of 27 April 1988 | |

| Metallurgy-Iron and Steel Industryb | Clarifies Art. 52 of its Work Regulation of 27 July 1946 (RCL 1946\1220 and 1739); night surcharge | Resolution of 25 March 1947 |

| Vigilance and safety | Extra-statutory agreement for companies | Resolution of 2 August 1989 |

| Sociedad Estatal de Correos y Telégrafos, SA [National Postal Service of Spain]b | Approves the Statute on Personnel of Sociedad Estatal de Correos y Telégrafos, SA | Royal Decree No 370/2004 of 5 March |

| Social Welfare Schoolsb | Authorises the transformation of “San Vicente de Paúl” of Zaragoza into the Social Work University, part of the University of Zaragoza | Royal Decree No 1788/1986 of 1 August |

| Centrers for general basic, pre-school and baccalaureate education, and vocational trainingb | Instructions on the organisation and operation of institutions that are publicly funded and supported by the Ministry of Education and Sciences | Order of 9 June 1989 |

| Baccalaureateb | Regulates baccalaureate night classes | Order of 1 August 1978 |

| Gives Instructions for the application of the Order of 20 July 1998 (RCL 1998\1835), which orders and organises Baccalaureate night classes | Resolution of 28 July 1998 | |

| Civil Aviationc (in part) | Determines the medical requirements necessary to obtain the class 3 aeronautical medical certificate referred to in the Air Traffic Controller license | Order No FOM/2418/2007 of 25 July |

| Region of Murciab | Transfer of functions and services of the State Administration in labour matters (enforcement of labour laws) | Royal Decree No 375/1995 of 10 March |

| Balearic Islandsb | Royal Decree No 98/1996 of 26 January | |

| La Riojab | Royal Decree No 946/1995 of 9 June | |

| Castile and Leónb | Royal Decree No 831/1995 of 30 May | |

| Castilla-La Manchab | Royal Decree No 384/1995 of 10 March | |

| Cantabriab | Royal Decree No 1900/1996 of 2 August | |

| Extremadurab | Royal Decree No 642/1995 of 21 April | |

| Principality of Asturiasb | Royal Decree No 2090/1999 of 30 December | |

| Aragonb | Royal Decree No 572/1995 of 7 April | |

| Autonomous Community of Madridb | Royal Decree No 932/1995 of 9 June |

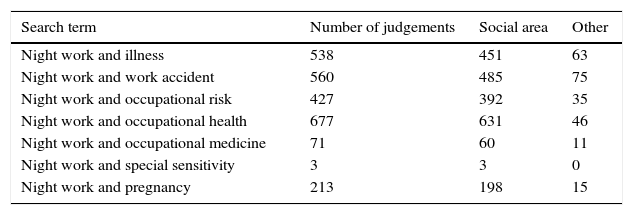

From a jurisprudential point of view, cases on this topic are mainly focused on the social area and on the involvement of occupational health. Cases related to the concepts of illness, work-related accidents and occupational risk that accompany night work are numerous. Also noteworthy are the cases relating night work and pregnancy (Table 3).

Jurisprudential review of night work and associated concepts.

| Search term | Number of judgements | Social area | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Night work and illness | 538 | 451 | 63 |

| Night work and work accident | 560 | 485 | 75 |

| Night work and occupational risk | 427 | 392 | 35 |

| Night work and occupational health | 677 | 631 | 46 |

| Night work and occupational medicine | 71 | 60 | 11 |

| Night work and special sensitivity | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Night work and pregnancy | 213 | 198 | 15 |

A review of Spanish jurisprudence in the Westlaw Insignis database, focusing on conflict generated by night work in sensitive groups: pregnant women, minors and sensitive workers.

One of the first cases relating to the risk of night work and pregnancy, under European directive 76/207/EEC, is the “Case of Gabriele Habermann-Beltermann v. Arbeiterwohlfahrt”38 which is still considered a reference today. In 1994, it proposed equal treatment for men and women in access to employment, training, professional advancement and working conditions, which in this case resulted in the annulment of an employment contract of a pregnant woman hired for night work. This contract specified that the woman concerned would be placed exclusively in the night service, which was the reason why the woman initiated a leave “due to illness” with the cause being pregnancy.

Against this, the Arbeiterwohlfahrt invoked Article 8(1) of the Mutterschutzgesetz (Maternity Protection Act) to terminate the contract of employment: Overtime, night work and Sunday work. Pregnant women and nursing mothers may not work or perform overtime at night, between the hours of 20:00 and 06:00, or on Sundays and public holidays. This prohibition does not apply to pregnant women or to nursing mothers employed in domestic work in a family.

The breaking of an employee's employment contract due to pregnancy, whether through a declaration of nullity or through a contestation, affects only women and therefore constitutes direct discrimination based on sex, as the Court of Justice held with regard to the refusal to employ a pregnant woman or to her dismissal.

This groundbreaking decision involved the submission of claims by the German, Italian and UK governments and the European Commission, which were overturned by the European Court of Justice on the questions posed by the Arbeitsgericht Regensburg-Kammer Landshut, through Resolution of 24 November 1992:

Article 2(1), in conjunction with Articles 3(1) and 5(1) of Council Directive 76/207/EEC of 9 February,39 on the implementation of the principle of equal treatment for men and women as regards access to employment, vocational training and promotion, and working conditions, precludes an employment contract of indefinite duration concerning night work and concluded between an employer and a pregnant worker, both of whom do not know about the pregnancy, on the one hand, being declared null and void on account of the legal prohibition of night work which applies, under national law, during pregnancy and breast-feeding, and, on the other hand, contested by the employer because of an error in the essential qualities of the worker at the time the contract was concluded.

The 2000 “Silke-Karin Mahlburg v. Land Mecklenburg-Vorpommern” case continues on the same lines with regard to the equal treatment of men and women in access to employment and working conditions (Directive 76/207/EEC). In this case, this was due to the employer's refusal to hire a pregnant woman, applying the principle of protection for the performance of certain jobs. The European Court ruled on the question posed by the Landesarbeitsgericht Mecklenburg-Vorpommern:

Article 2(1) and (3) of Council Directive 76/207/EEC of 9 February 1976, on the implementation of the principle of equal treatment for men and women as regards access to employment, vocational training and promotion, and working conditions, opposes the refusal to hire a pregnant woman for an indefinite post on the grounds that a legal prohibition of work linked to that status prevents her, during her pregnancy, from occupying the post in the first place.

At present, Spanish legislation protects pregnant women, minors and especially sensitive workers, under Art. 25 of Act 31/1995 and Art. 36(4) of the WS, in risk prevention, regulating the obligation of employers to evaluate such risk and implement the relevant protective and preventive measures. The “2001 decision of the High Court of Justice of the Canary Islands, Las Palmas (Social Affairs Division)” was a reference in this matter,40 later endorsed in 2008 by the “High Court of Justice of Navarra, 1st Social Affairs Division”,41 on the basis of the type of working day considered to constitute night work, under Directive 93/104, ensuring workers’ health and safety and adequate compensation for night work. Part of the thinking is that ordinary work must be done in the daytime and that night shifts or work should be described as particularly burdensome and difficult, because they seriously affect the health of the worker, and that the alteration of circadian rhythms implies variations in physiological functioning and disturbances in the sleep cycle, schedule and sequence of meals, and in the worker's family and social relationships.

The hardship involved with night work requires the employer to enhance measures of hygiene and safety for workers. Article 9(1) of that directive expressly states: (b) night workers suffering from health problems recognised as being connected to the fact that they perform night work must be transferred whenever possible to day work for which they are suited; this guideline serves as a model for Art. 36(4) of the WS, meaning that it is the company's owner who assumes the burden of monitoring the health and working conditions of night workers through mandatory periodic tests. The International Labour Organisation also has a number of conventions and recommendations which set criteria for night work and show a specific concern, such as Recommendation R 178 on night work, which is restricted to the assumption of an adequately justified need for production, under guaranteed conditions of hygiene and safety, and to specially skilled workers.

In the case involving this decision, the health problems in the worker coinciding with the night shifts caused the Court to accept the difficult and stressful nature of night work for the worker, which must be reserved for healthy and suitable workers, whereas in this case the plaintiff had objective circumstances enabling him/her to demand a change of shift under the preventive regulations.

ConclusionsThis review on night work can be concluded by stating that it forms part of business organisation and can be performed by all workers, provided they are not included in the exceptional situations described by the regulations, and in all cases is subject to compliance with the principles of protection and prevention established by current legislation.

In occupational health, the concern about effects on workers’ health, especially in those of “special sensitivity”, is highlighted. The most recent medical literature highlights cancer, although the results are subject to further, more conclusive studies.

Occupational physicians have a duty to support preventive work through specific health monitoring, which for these workers is mandatory.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Vicente-Herrero MT, Torres Alberich JI, Capdevila García L, Gómez JI, Ramírez Iñiguez de la Torre MV, Terradillos García MJ, et al. Trabajo nocturno y salud laboral. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2016;42:142–154.