A 39.5 % of violent deaths that occurred in Spanish prisons were drug-related deaths.

In this study, we assess the role of abused drugs and prescribed psychoactive drugs in a cohort of prison deaths cases along three years.

Materials and methodsA cohort of 40 cases were received during the period 2021–2023. Each of them was classified following several parameters: sex, age, pathologies, pharmacologycal treatment, reported cause of death and toxicologycal analysis (analysed samples and detected substances following analytical routine).

ResultsA 82.5 % of cases submitted (n = 33) were classified as violent deaths: suicide by hangling (39.4% n = 13) and drug-related deaths (60.6 % n = 20). The Victim's profile was a man with a mean age of 39.5 years old, who suffered from a mental disease and had been prescribed a medical treatment mainly with psychoactive drugs.

In cases of suicide by hangling, toxicologycal analysis revealed psychoactive drug consumption, such as benzodiazepines and gabaergic drugs. On the other hand, in drug-related death cases, polyconsumption involving abuse drugs and prescribed drugs was prevalent.

DiscussionThe whole of violent death cases showed a positive toxicologycal result. In regard to these results, we should highlight the absence of alcohol, and the polyconsumption of prescribed and not prescribed psychoactive drugs involving abuse drugs in those cases where polydrug intoxication was reported as a cause of death. Abuse drugs detected corresponded with consumption patterns in Spanish society.

Un 39,5 % de muertes violentas ocurridas en centros penitenciarios españoles, se relacionaron con reacciones adversas a drogas de abuso. En este estudio evaluamos el papel de drogas de abuso y psicofármacos en un conjunto de casos de muertes penitenciarias a lo largo de tres años.

Material y métodosUn total de 40 casos fueron recibidos durante el período 2021–2023. Cada uno de ellos fue estudiado siguiendo una serie de parámetros: sexo, edad, patologías previas y tratamiento médico, causa reportada de la muerte y análisis químico toxicológico (muestras analizadas y sustancias detectadas siguiendo la sistemática analítica de rutina).

ResultadosUn 82,5 % de casos (n = 33) se correspondieron con muertes violentas: ahorcadura (39,4 % n = 13) y muertes atribuidas a reacciones adversas a sustancias psicoactivas (RASUPSI) (60,6 % n = 20). El perfil del fallecido fue de un hombre, de edad media 39,5 años, con alguna patología psiquiátrica y en tratamiento con psicofármacos.

En los casos de ahorcadura el análisis químico-toxicológico reveló consumo de psicofármacos, fundamentalmente benzodiazepinas y gabaérgicos, mientras que en los casos de muerte RASUPSI, predominó el policonsumo de psicofármacos y drogas de abuso (85 % n = 17).

DiscusiónEn todos los casos de muerte violenta hubo un resultado toxicológico positivo, donde debemos destacar la ausencia de consumo de alcohol, el policonsumo de psicofármacos en mayor número de los incialmente prescritos, y su combinación con drogas de abuso fundamentalmente en aquellos casos donde la muerte se relacionó con el consumo de sustancias. Las drogas de abuso detectadas se correspondieron con aquellas mayoritariamente consumidas en la sociedad española.

Deaths in prison, and specifically those due to unnatural causes, are of particular interest from a medical-legal point of view, given that inmates are under the guardianship of the prison administration.

Violent deaths accounted for 41.5 % of the total deaths recorded in Spanish penitentiary centres in 2021, according to data collected by the General Secretariat of Penitentiary Institutions of the Ministry of the Interior,1 and referring to all penitentiary establishments in the national territory, except those located in the autonomous communities of Catalonia and the Basque Country.

Of this percentage, similar to that recorded in 2020 (43.6 %), the majority corresponded to suicides (47.3 %), followed by deaths related to adverse reactions to drugs of abuse (39.5 %). The rest of the violent deaths, consequences of accidents or assaults, accounted for 13.2 % of the cases.2

Various studies conducted in developed countries showed that violent deaths in penitentiary centres ranged between 48 % and 59 % of all deaths, with the majority of these deaths being due to suicide.3

In this regard, based on the requests for chemical-toxicological analyses addressed to the Madrid department of the National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences in cases of violent deaths occurring in penitentiary centres, we thought it appropriate to carry out a study of these cases in order to contribute to a greater understanding of the role of psychoactive substances in this type of death.

The main objective of this study was therefore to evaluate 40 cases of deaths in penitentiary centres received by the Drug Service of the National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences (Madrid department) in the period between 2021 and 2023.

The Madrid department of the National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences provides coverage to a territory where 24 penitentiary centres are located, distributed in the autonomous communities of Madrid, Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla y León, Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, La Rioja, the Basque Country and Murcia.

Based on the general objective expressed above, we established specific objectives, the first of which was the identification and classification of psychoactive substances (alcohol, drugs of abuse and psychotropic drugs) found in the samples from the autopsies. Other objectives were the determination of the prevalence of each group of substances, as well as the contribution of their consumption in the causes of death.

Material and methodsStudy descriptionA single-centre retrospective study was conducted using data obtained from two different sources: the toxicological analysis request forms submitted in each case by the forensic doctors to the National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences, as well as the results of the analyses performed on the biological samples sent.

For each case, a series of variables were established for study:

- •

Data corresponding to the inmate

- •

Sex

- •

Age

- •

Previous illnesses

- •

Medical treatment

- •

- •

Reported cause of death

- •

Chemical-toxicological analysis

- •

Biological samples analysed (blood, urine, vitreous humour)

- •

Substances detected

- •

Ethyl alcohol

- •

Drugs of abuse (cannabis, opiates, cocaine and amphetamines)

- •

Psychotropic drugs (methadone, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, antidepressants and antipsychotics).

- •

- •

Information about the inmate, as well as the cause of death, was provided in all cases by the forensic doctors. The biological samples, mainly blood, vitreous humour and urine, were subjected to the routine toxicological analysis of the drug service.

Blood and vitreous humour samplesFirst, an analysis of volatiles in blood was performed, with special attention to ethyl alcohol, using gas chromatography with a flame ionisation detector and headspace analyser (GC-FID-HS).

The analysis of cannabinoids was carried out in blood samples using gas chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (GC–MS/MS), and the rest of the organic toxins (drugs of abuse and psychotropic drugs) were analysed in blood and vitreous humour by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) in MRM (MultipleReactionMonitoring) mode.

Urine samplesUrine samples were first subjected to a presumptive analysis using the CEDIA (Cloned-Enzymed Donor Immunoassay) enzyme immunoassay to determine positivity for a group of substances (cocaine and metabolites, opiates, methadone, cannabinoids, amphetamines, benzodiazepines, barbiturates and antidepressants) and thus guide subsequent confirmatory analysis using chromatographic techniques. Positive results for any of the groups of substances tested were confirmed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) in the case of cannabinoids, or by UPLC-MS/MS for the rest of the substances.

ResultsA total of 40 cases of prison deaths were evaluated, 6 of which (15 %) were deaths of natural origin and one of which was a violent death of accidental aetiology due to mechanical asphyxia. The cases under study (82.5 %; n = 33) corresponded to violent deaths that we classified into 2 large groups: deaths due to mechanical asphyxia by hanging, of clearly suicidal aetiology (39.4 %; n = 13), and deaths attributed to acute reactions to psychoactive substances (ARPS), (60.6 %; n = 20). In this last classification, we have not been able to specify whether they are deaths of suicidal or accidental aetiology, given that ARPS deaths can encompass both cases.

The majority of the deceased were men (87.9 %; n = 29) with an average age of 39.5 years. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of the victims according to age ranges.

In 72.7 % of the cases (n = 24), previous illnesses were described, almost all of them (n = 23) being psychiatric illnesses, mainly those related to dependence on psychoactive substances.

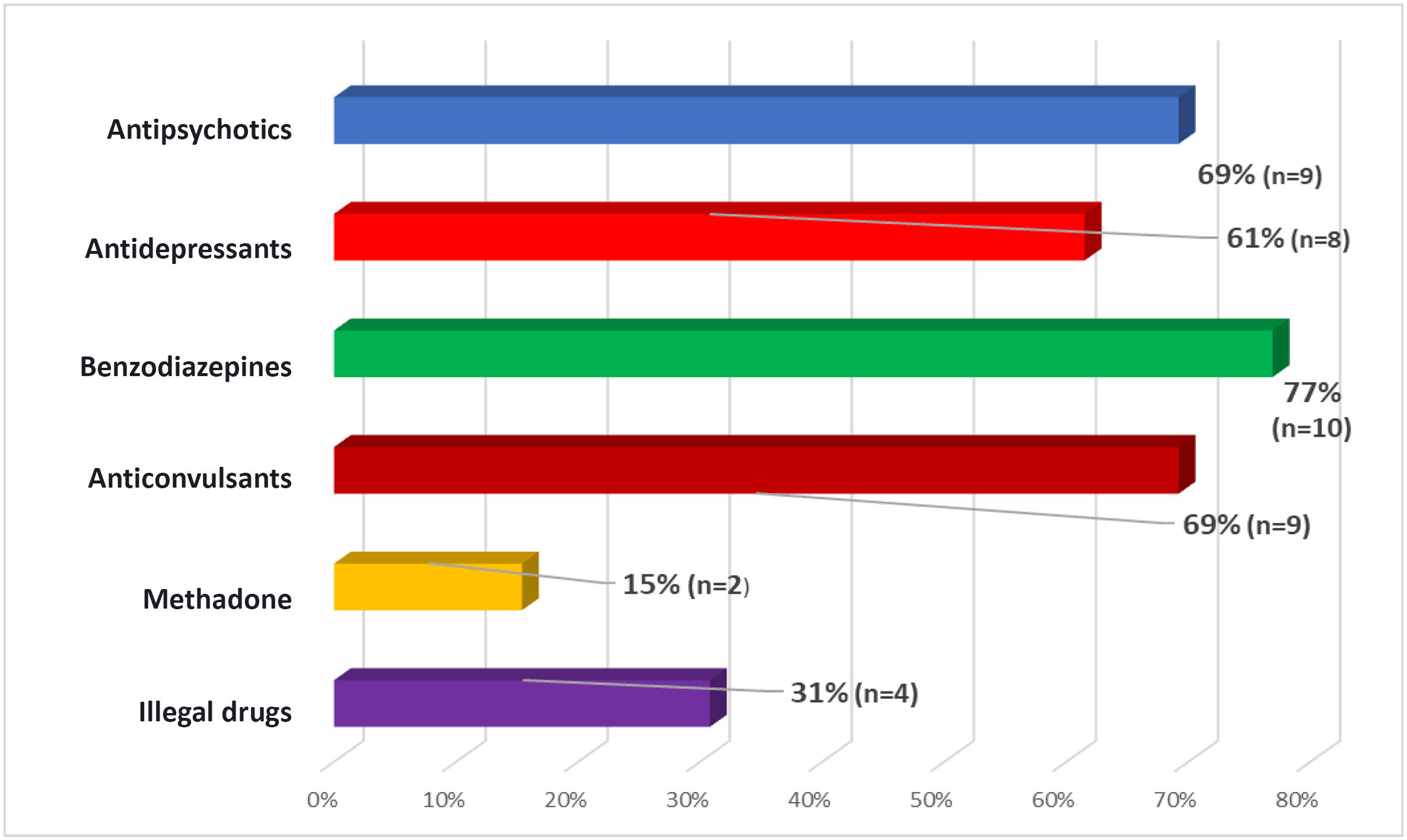

Regarding the therapeutic treatments prescribed, these were reported in 63.6 % of the cases (n = 21) and were all psychotropic drugs (benzodiazepines, antidepressants, etc.).

Regarding the chemical-toxicological analysis, blood samples were sent in all cases, while urine samples were only sent in 51.5 % of the cases (n = 17) and vitreous humour samples in 36.4 % of the cases (n = 12). These 3 samples were analysed in all those cases in which they were sent. Likewise, all the analyses performed recorded positive results for drugs of abuse and/or psychotropic drugs, but not for ethyl alcohol, the presence of which was not detected in any of the samples.

In the cases of suicides by hanging (n = 13), Fig. 2 shows that there was prior consumption of psychotropic drugs in all cases, and in 30.8 % of them (n = 4), they were detected in combination with drugs of abuse. Of the 11 cases of this type of death in which information on therapeutic treatments appears, only 2 of them (18.2 %) were prescribed psychotropic drugs exclusively detected, with a greater number of substances detected in the rest than would be expected based on the reported treatment. Fig. 3 shows the distribution of substances detected.

In cases of deaths attributed to substance use (ARPS; n = 20), Fig. 4 shows that the combination of drugs and psychotropic drugs was recorded in the majority of cases (85 %; n = 17). Fig. 5 shows that there was use of more than 3 psychoactive substances in 80 % of cases (n = 16).

Of the 17 cases where information on therapeutic treatment was available, in 94 % (n = 16), a greater number of psychotropic drugs than those prescribed were detected, alone or in combination with drugs of abuse.

Fig. 6, for its part, describes the distribution of the substances detected in ARPS deaths.

(Note: in the classification of anticonvulsants, we refer exclusively to gabapentin and pregabalin).

DiscussionAccording to inmate data, the majority profile of the violent death victim was that of a male between 34 and 45 years old, with some form of mental illness and undergoing psychiatric treatment. The prevalence of male victims is consistent with the fact that 9 out of 10 inmates in Spanish prisons are male.1 Regarding psychiatric illnesses, according to the statistics of the General Secretariat of Penitentiary Institutions, 48.5 % of admissions to the infirmaries of penitentiary centres were motivated by this type of illness.1

Substance-related disorders, whether alcohol, drugs of abuse or psychotropic drugs, constitute the most frequent psychiatric illnesses in the prison population, followed by affective disorders and disorders of psychotic origin.4

Related to the above, the Survey on Health and Drug Use in the Inmate Population in Penitentiary Institutions corresponding to 2022 revealed that 7 out of 10 inmates admitted to having used illicit drugs while at liberty (75.1 %), with 2 out of 10 admitting to having used them in prison over the last month (16.8 %).1

The relationship between mental disorders, substance use and deaths in prison has also been the subject of study in other countries. Vaughan et al. studied the link between deaths in custody and mental illness linked to substance use in Ontario (Canada) between 1996 and 2010. The researchers, after studying 478 cases of deaths in custody, concluded that 32.6 % of them were related to some mental illness linked to substance abuse.5

There are, however, a series of variables about the profile of the deceased that would have been interesting to include in this study, but this has not been possible due to the lack of information on these aspects: crimes committed, criminal procedural situation or recent prison permits.

With regard to the reported causes of violent deaths, the prevalence of this type of death varies with respect to those included in the Report of the General Secretariat of Penitentiary Institutions in 2022. Although in official statistics, deaths from suicidal aetiology predominated in 2021 47.3 %),1 in our study, the main cause of violent death was related to polydrug use, mainly: drugs of abuse and psychotropic drugs (60.6 %) without, sometimes, being able to elucidate an accidental or suicidal aetiology.

We therefore opted to use the suicide classification for all cases of death where the mechanism of death clearly corresponds to a suicidal intention on the part of the deceased, as is the case of mechanical asphyxiation by hanging. This mechanism turned out to be the only one recorded in these cases, as well as the prevalent mechanism in deaths by suicide in Spain.6 Likewise, suicide by hanging was also the main cause of death in the study that Voulgaris et al. carried out in Berlin prisons between 2012 and 2017.7

However, according to the results of our study, all the chemical-toxicological analyses carried out on suicide victims yielded a positive result for drugs of abuse and/or psychotropic drugs, with a prevalence of psychotropic drugs, as reflected in Fig. 2.

The presence of psychoactive substances, mostly non-prescribed psychotropic drugs, can be interpreted as a consequence of the prevalence of psychiatric illnesses among the deceased, together with a possible exchange of psychotropic drugs among the inmates themselves. It is also not unreasonable to think of possible “complex suicides”, where the individual combines different methods, such as hanging, together with the ingestion of substances, aimed at ensuring death.

The toxicological findings in victims of suicide by hanging were also collected by Iqtidar et al., in a retrospective study carried out over 5 years in Irish prisons, revealing that 66.7 % of this type of death yielded positive toxicological results.8

Although in the analyses carried out in cases of suicide psychotropic drugs predominate, in cases of ARPS deaths, the combination of drugs of abuse and psychotropic drugs is prevalent (Fig. 4). These were cases of polydrug use, which mostly involved more than 3 substances (Fig. 5).

As in the cases of suicide, in almost all cases of ARPS deaths, a greater number of psychotropic drugs were detected than those listed as prescribed, except that in these cases, they were presented in combination with drugs of abuse.

The prevalence of psychotropic drugs was similar in both categories of violent deaths, Benzodiazepines were the predominant group detected in all cases, followed by anticonvulsants, where we refer specifically to gabapentin and pregabalin. Regarding benzodiazepines, if we compare the results of our study with the data provided by the Survey on Alcohol and Drugs in Spain (EDADES) for 2022, we observe a coincidence in the prevalence of consumption of sedative-hypnotics such as benzodiazepines, which has shown an increasing trend in Spain since 2018. As a result, these psychotropic drugs were involved in 66.3 % of ARPS deaths in 2021.9

Regarding pregabalin and gabapentin, both GABAergic psychotropic drugs always appeared in combination, with the consequent potentiation of toxic effects due to the concurrent consumption of 2 psychotropic drugs with the same mechanism of action. Although they were initially prescribed for the treatment of pain and convulsions, their therapeutic use has been extended to cases of bipolar disorder, anxiety and insomnia.10 This extension of the therapeutic spectrum of both psychotropic drugs will undoubtedly be related to their prevalence in the cases analysed.

Antipsychotics, antidepressants and methadone complete the list of groups of psychotropic drugs detected. In this sense, methadone is the psychotropic drug with the lowest prevalence, which is undoubtedly related to the continued decline since 2001 in the number of inmates undergoing substitution therapy for withdrawal from this opioid.1

Regarding drugs of abuse, cannabis was the most widely consumed substance. This matches official data, according to which it is the most widely consumed drug in prison.1 Opioids (heroin) and cocaine were the other two groups of illicit substances detected in deaths from polydrug use.

It is worth highlighting here that there was an absence of drugs classified within the so-called group of New Psychoactive Substances or NPS. These include a group of substances that have recently appeared on the illicit market and that were not initially controlled by the United Nations in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961 or in the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 (derivatives of cathinones, piperazines or synthetic cannabinoids, among others). These compounds are gradually being subjected to control as the different positional isomers that appear in illicit preparations are characterised. As this characterisation is carried out by forensic laboratories, these new compounds are incorporated into the routine analyses of our laboratory. However, none of these substances were detected in the cases originating from penitentiary centres.

This is a significant difference with the studies on drugs of abuse in penitentiary centres carried out in other countries such as the United Kingdom, where seizures of NPS have increased since 2017, reaching 9114 in 2021.11 However, examining the seizures from penitentiary centres and received in the analysis section of substances in caches of our laboratory between the years 2021 and 2023 (493), we verified the absence of NPS, with the most commonly seized substances being cannabis, cocaine, heroin and psychotropic drugs, such as benzodiazepines and gabapentin.

The detection of cannabinoids as the most commonly involved drug of abuse is a fact that coincides with the prevalence of its consumption in Spanish society (EDADES 2022). However, the presence of opioids (heroin) in 45 % of deaths contrasts with its low consumption figures,9 although on the contrary, it matches its presence in 55.7 % of ARPS death cases in Spain in 2021. In this sense, Iqtidar et al. identified opioids and benzodiazepines as the substances most commonly involved in deaths related to substance use in prison.8

The absence, likewise, of amphetamine derivatives (amphetamine, methamphetamine or MDMA) is another characteristic that draws attention, despite the fact that in 2022, there was an increase in the consumption of these substances,9 known as ecstasy, speed, or crystal. The combination of ketamine and MDMA, which has gained popularity under the name “tusi” or “pink cocaine”, does not appear among the illicit substances consumed in prisons. It does not therefore represent a consumption pattern for inmates.

However, if we have to mention a difference between the consumption pattern of psychoactive substances in Spain and the findings of this study, we must point to the absence of alcohol, taking into account that it is the most consumed psychoactive substance in our society.9 Without a doubt, the controls and restrictions applied in prisons prevent the entry of alcoholic beverages, hence the absence of positive cases for alcohol. The same does not occur with drugs of abuse, which circulate in prisons despite the controls. The ease of hiding them, compared to alcohol, is undoubtedly the reason why security measures can be circumvented, allowing illicit substances to be introduced into the centres.

To conclude, we cannot speak of a group of psychoactive substances that are consumed mostly or exclusively in prisons, different from the pattern of substance consumption reflected in the statistics referring to the population as a whole. In other words, there is a permeability between society and the penitentiary environment in terms of the consumption of psychoactive substances, such as in the cases of benzodiazepines and drugs that we could classify as “classic” (cannabis, cocaine and heroin), with the notable exception of ethyl alcohol.

Likewise, the reinforcement of measures against drug trafficking within penitentiary centres, as well as the review of psychiatric treatments with psychotropic drugs from a toxicological perspective and greater control in the dispensing of these to avoid non-therapeutic consumption, are actions that, in light of the data obtained, we consider could contribute to tackling the problem of ARPS deaths in prison.

Finally, as limitations of this study, we should highlight that the Madrid department of the National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences does not receive reports of all the cases of deaths that occur in penitentiary centres located in its territorial area.

Please cite this article as: García Caballero C, Martínez González MA. Deaths in prison: Toxicological findings in cases analysed at the National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences (Madrid) during the period 2021–2023. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.remle.2025.100428.