To describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of a population of children under 12 years submitted to forensic sexual examination and the proportion of confirmed cases of sex abuse by material evidence.

Material and methodsA retrospective descriptive study was conducted by reviewing all examination reports of forensic sexology for suspicion of child sexual abuse carried out at the forensic institute of Salvador, Brazil, between 2005 and 2010.

ResultsDuring the study period, 2802 children under 12 years with suspicion of sexual abuse were submitted for forensic examination. The mean age was 6.6 years (SD 3.09), and 78.4% were female. In 84.9% of the cases, examination was required based on previous allegations of sexual abuse. The physical examination showed no alteration in 67.0% of the children investigated. The proportion of confirmed cases of sexual abuse by material evidence was 8.9% (248 cases).

ConclusionIn view of the consensus of the low proportion of false allegation of sexual abuse made by children found in the specialized literature, the data obtained in this study emphasize the low sensitivity of the forensic examination for the confirmation of sexual abuse by material evidence, as well as the need for the comprehension of this fact by all those to whom these examinations are intended.

Describir las características demográficas y clínicas de la población de menores de 12 años sometidos a pericia de sexología forense y la proporción de los casos confirmados de abuso sexual por prueba material.

Material y métodosEl diseño fue un estudio descriptivo retrospectivo. Se revisaron todos los informes de examen de sexología forense por sospecha de abuso sexual en menores de 12 años, que fueron realizados por el instituto médico-forense de Salvador, Brasil, en el periodo de 2005–2010.

ResultadosEn el periodo estudiado, 2.802 menores de 12 años fueron sometidos a examen de sexología forense por sospecha de abuso sexual. La edad media fue de 6,6 años (DT 3,09). Del total de menores examinados, 78,4% eran niñas. En cuanto al motivo de la pericia, en el 84,9% de los casos hubo en la historia clínica un relato de abuso sexual. En el 67,0% de los menores examinados no fue detectada ninguna alteración en el examen físico. La proporción de casos confirmados de abuso sexual por prueba material fue de 8,9% (248 casos).

ConclusionesAnte el consenso en la literatura de la pequeña proporción de falsos relatos de abuso sexual efectuados por menores, los datos encontrados en este estudio resaltan la baja sensibilidad del examen del cuerpo del delito para la confirmación de abuso sexual por prueba material y la necesidad de que esto sea comprendido por todos aquellos a quienes se destinan los informes de dichos exámenes.

Child sexual abuse can be understood as sexual experiences with or without contact between a minor and another person, at least 5 years older; or sexual experiences involving a minor resulting from coercion, regardless of the age of the aggressor.1

Studies from various countries2 show that child sexual abuse is a major global public health problem. A meta-analysis3 that includes data from 22 countries estimated that 7.9% of men and 19.7% of women were the victims of some kind of sexual abuse before reaching the age of 18 years. In another meta-analysis that includes 217 publications,4 the prevalence of child sexual abuse based on self-reporting was 18.0% for females and 7.6% for males.

For a global understanding of this problem, studies from different data sources are required, including population studies, and case studies in hospitals, medical-forensic institutes and agencies for the protection of minors.

Population-based research on child sexual abuse has been conducted through questionnaires completed by adolescents and adults several years after the events. In spite of having the advantage of providing incidence and prevalence data, many variables remain which cannot be evaluated and there are ethical questions involved which make its performance difficult in many contexts.5 Studies conducted in hospitals, medical-forensic institutes and agencies for the protection of minors, facilitate the study of recent cases and the collection of a differentiated set of variables, and are thus complementary to the population studies.

In the Brazilian Criminal Code,6 up to the year 2009, 2 types of sexual violence crime were provided for: rape and violent indecent assault. Rape was considered to be the act of “forcefully gaining carnal access to a female without consent, using violence or serious threat”. Violent indecent assault was defined as “forcing someone, through violence or serious threat, to practice or allow the practice with him of a libidinous act apart from consented carnal access”. With the sanction of Law No. 12,015, of August 7, 2009,7 the description of “violent indecent assault” was removed and the types of acts previously classified as such were now considered as rape. The criminal concept “rape of the vulnerable” was also created, defined as “having carnal relations or practicing other libidinous acts with children under the age of 14 years old”, replacing the description of “presumption of violence” which existed for children under the age of 14 years.

The Child and Adolescent Statute,8 in force in Brazil since 1990, stipulates that cases of suspected or confirmed abuse against children or adolescents are mandatorily reported to the Council of Guardianship of the respective locale, without prejudice to the other legal rulings. This law considers children as those under the age of 12 years and adolescents as those of 12 years or older and under 18. The Council of Guardianship is the permanent and autonomous organ, in charge of ensuring compliance with the rights of the child and the adolescent. According to the Child and Adolescent Statute, there is no hindrance to victims of sexual abuse being referred by the Council of Guardianship directly to the existing multidisciplinary care services without prior examination by a forensic doctor. Nevertheless, in practice, the majority of cases of suspected child sexual abuse that reach the competent authorities are referred to the medical-forensic institutes for forensic physical examination for the possible detection of forensic traces even in cases of a report of past abuse. In addition to the still current culture of treating child abuse cases with the model of adult cases, this practice is reinforced by the fact that victim multidisciplinary care network is still being consolidated in the country and is barely present in the large cities. Forensic physical examinations are stipulated by the Brazilian Procedural Penal Code,9 Law 003.689 of 1941, in its Article 158: “When the infraction leaves traces, the direct or indirect forensic physical examination shall be indispensable, and cannot be substituted by a confession from the accused”.

In Brazil, forensic medicine is associated with the judicial police force in the majority of the federation's states. The judicial police force's primary function is to resolve criminal acts and their perpetrators through police investigation supervised independently by the police commissioner, and directed to the Judicial Branch upon conclusion.

The World Health Organization has warned that the lack of data hinders the ability to respond effectively to the abuse of a minor and highlights the need to quantify and monitor the dimension of the problem on a global, regional and national level.5

There are few studies in Brazil on child sexual abuse, gathered from police sources,10–13 and there is still a lack of data regarding the characteristics of this population in our context.

The purpose of this work is to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of the population of children under 12 years of age subject to forensic physical examinations due to suspected sexual abuse, and to show the ratio of cases confirmed by the forensic doctor.

Material and methodsThe design was a descriptive, retrospective study.

SampleThe population studied included children under the age of 12 referred for forensic physical examination at the Instituto Médico Legal Nina Rodrigues [Nina Rodrigues Legal Medical Institute] (IMLNR). The sample included all consecutive reports of forensic physical examinations which met the eligibility criteria: (1) forensic sexology report for suspected sexual abuse; (2) under 12 years of age. This age group coincides with that adopted by the legal description a child in force in Brazil, established by the Child and Adolescent Statute.

IMLNR is the reference site for all corpus delicti examinations for the Metropolitan Region of Salvador, including those of forensic sexology. The Metropolitan Region of Salvador is made up of 13 municipalities and in the 201014 census, there were 3,574,804 inhabitants.

InstrumentsThe data collection instrument was a standardized sheet developed for this research. In the forensic reports, the following data was collected from the minors presumed to be victims or sexual abuse: date of the forensic assessment, place of birth, municipality of residence, reason for the forensic assessment, presence or absence of an account of sexual abuse in the history, companion who recounted the history, presence or absence of an interview with the victim, presence in the report of a description of the words used by the minor during the interview, sex of the minor, age, aggressor information (number, sex, type of connection with the minor), and forensic conclusion. The forensic conclusion variable was classified into 6 categories: 1 – cases with no changes upon physical examination; 2 – presence of findings in the physical examination classified as non-specific by the forensic doctor; 3 – cases of sexual abuse confirmed by the forensic doctor; 4 – cases of accounts of accidental anogenital trauma in which the forensic doctor did not find any indications of sexual abuse; 5 – cases of illness confused with sexual abuse; 6 – others.

ProceduresThe data was drawn from the forensic sexology exam reports for suspected sexual abuse in children under 12 conducted at the IMLNR, during the period from January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2010.

Sexology exams are conducted by duty forensic doctors at the Institution and consist of interviews with the victim and/or family members, physical examination and collection of laboratory tests (pregnancy tests to screen for chorionic gonadotropin hormone, screening for sperm with microscopic examination, and screening for specific prostatic antigens as an indicator of semen) in accordance with the forensic findings. Although the interviews are part of the forensic exam, the conclusions of forensic doctors adhere to the material findings encountered, given that the prevailing understanding in medical-forensic doctrine is that the objective of the forensic exam in the criminal sphere is to describe that which is observable based on the visum et repertum principle, and to draw conclusions15 from this.

For ethical reasons, identification data was not collected in order to maintain the privacy of the victims and prevent interference in the police investigation. The statistical analysis used the SPSS v. 14.0 for Windows16 programme and included the description of absolute and relative frequencies for categorized variables; frequencies, means or medians, typical deviation or interquartile range (IQR) 25–75%, for the numeric variables. This study was approved by the Escuela Bahiana de Medicina y Salud Pública [Bahiana School of Medicine and Public Health] Research Ethics Committee under protocol 068/10 and the collection of data was authorized by the IMLNR.

Results2802 minors under 12 years of age were examined for suspected sexual abuse at the IMLNR from January 2005 to December 2010. The average age was 6.5 years (SD 3.09) ranging in age from 19 days to 11 years old.

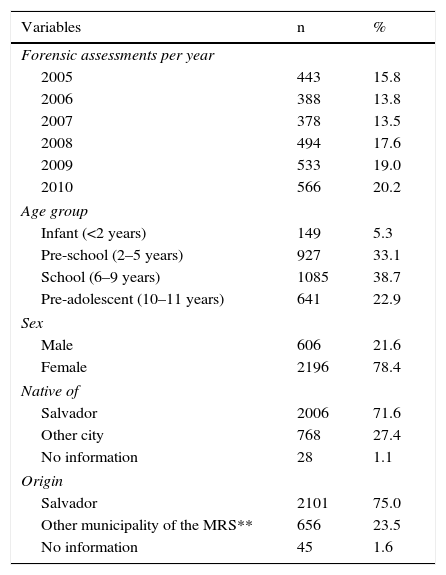

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the population studied. There was a predominance of girls (78.4%), and the majority were from the municipality of Salvador (75.0%).

Children under 12 years old examined at the IMLNR* due to suspected sexual abuse: demographic data. Metropolitan Region of Salvador, Brazil, 2005–2010 (n=2802).

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Forensic assessments per year | ||

| 2005 | 443 | 15.8 |

| 2006 | 388 | 13.8 |

| 2007 | 378 | 13.5 |

| 2008 | 494 | 17.6 |

| 2009 | 533 | 19.0 |

| 2010 | 566 | 20.2 |

| Age group | ||

| Infant (<2 years) | 149 | 5.3 |

| Pre-school (2–5 years) | 927 | 33.1 |

| School (6–9 years) | 1085 | 38.7 |

| Pre-adolescent (10–11 years) | 641 | 22.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 606 | 21.6 |

| Female | 2196 | 78.4 |

| Native of | ||

| Salvador | 2006 | 71.6 |

| Other city | 768 | 27.4 |

| No information | 28 | 1.1 |

| Origin | ||

| Salvador | 2101 | 75.0 |

| Other municipality of the MRS** | 656 | 23.5 |

| No information | 45 | 1.6 |

IMLNR, Instituto Médico Legal Nina Rodrigues; MRS, Metropolitan Region of Salvador.

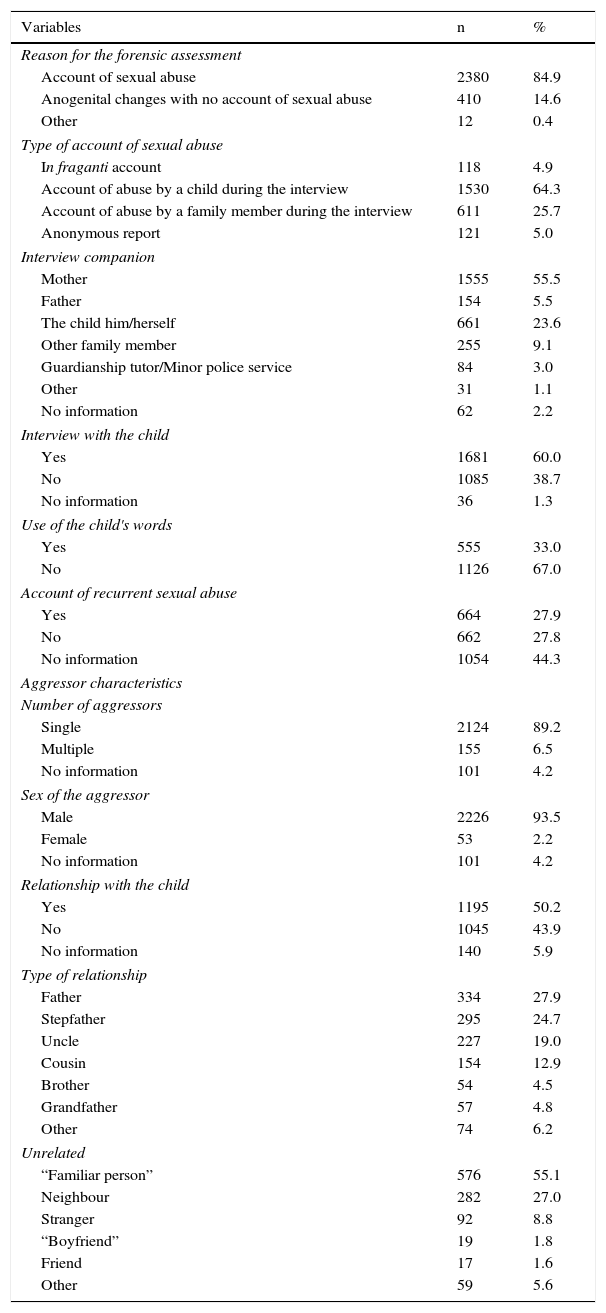

As for the reason for the forensic assessment (Table 2), in 2380 cases (84.9%) there was an account of sexual abuse. In 410 cases (14.6%), no account of sexual abuse appeared in the history, and the forensic exam was motivated by the presence of some change in the minor's anogenital region.

Forensic history information.

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Reason for the forensic assessment | ||

| Account of sexual abuse | 2380 | 84.9 |

| Anogenital changes with no account of sexual abuse | 410 | 14.6 |

| Other | 12 | 0.4 |

| Type of account of sexual abuse | ||

| In fraganti account | 118 | 4.9 |

| Account of abuse by a child during the interview | 1530 | 64.3 |

| Account of abuse by a family member during the interview | 611 | 25.7 |

| Anonymous report | 121 | 5.0 |

| Interview companion | ||

| Mother | 1555 | 55.5 |

| Father | 154 | 5.5 |

| The child him/herself | 661 | 23.6 |

| Other family member | 255 | 9.1 |

| Guardianship tutor/Minor police service | 84 | 3.0 |

| Other | 31 | 1.1 |

| No information | 62 | 2.2 |

| Interview with the child | ||

| Yes | 1681 | 60.0 |

| No | 1085 | 38.7 |

| No information | 36 | 1.3 |

| Use of the child's words | ||

| Yes | 555 | 33.0 |

| No | 1126 | 67.0 |

| Account of recurrent sexual abuse | ||

| Yes | 664 | 27.9 |

| No | 662 | 27.8 |

| No information | 1054 | 44.3 |

| Aggressor characteristics | ||

| Number of aggressors | ||

| Single | 2124 | 89.2 |

| Multiple | 155 | 6.5 |

| No information | 101 | 4.2 |

| Sex of the aggressor | ||

| Male | 2226 | 93.5 |

| Female | 53 | 2.2 |

| No information | 101 | 4.2 |

| Relationship with the child | ||

| Yes | 1195 | 50.2 |

| No | 1045 | 43.9 |

| No information | 140 | 5.9 |

| Type of relationship | ||

| Father | 334 | 27.9 |

| Stepfather | 295 | 24.7 |

| Uncle | 227 | 19.0 |

| Cousin | 154 | 12.9 |

| Brother | 54 | 4.5 |

| Grandfather | 57 | 4.8 |

| Other | 74 | 6.2 |

| Unrelated | ||

| “Familiar person” | 576 | 55.1 |

| Neighbour | 282 | 27.0 |

| Stranger | 92 | 8.8 |

| “Boyfriend” | 19 | 1.8 |

| Friend | 17 | 1.6 |

| Other | 59 | 5.6 |

In the group that presented accounts of sexual abuse during the interview, in 1530 cases (64.3%) the minor had already recounted the abuse suffered to someone and repeated it during the interview with the forensic doctor; in 611 cases (25.7%), it was the companion who informed the forensic doctor of the account of sexual abuse provided by the minor before the forensic assessment; in 118 cases (4.9%) there were accounts that the sexual abuse was discovered by somebody in fraganti; and in another 121 cases (5.0%), the reason for the forensic assessment was an anonymous report.

In the population studied, the minor was interviewed in 60.0% of cases (1681), and in 33.0% of those interviewed (555), the account was described in the forensic report using the words of the minor. The companion interviewed was the mother in 55.5% of the cases, the father in 5.5% and in 23.6% of the cases, there was no information on the companion, and only the account of the interview conducted with the minor was included.

As for the characteristics of the aggressor, 93.5% were male; 89.2% were alone; 50.2% had some relationship with the minor; and 8.8% were not known by the victim.

The median time period between the last sexual abuse episode reported and the forensic exam was 96h (RIQ 24–432) among cases with a positive account of sexual abuse.

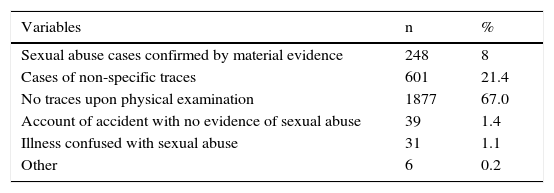

In relation to the conclusion of the forensic exam report (Table 3), there were 248 confirmed cases of sexual abuse with material evidence, corresponding to 8.9% of the population studied. In 1877 cases, 67.0% of the minors examined, no change was detected in the physical exam nor any other trace of sexual abuse. In 601 cases (21.4%), non-specific changes were identified in the genital or anal region, which were insufficient in terms of confirming sexual abuse. There were 31 cases (1.1%) in which the forensic medical expert identified in the conclusion of the forensic report an illness or anatomical variation as the cause of the anogenital alteration that motivated the forensic exam. These were cases with no account of sexual abuse in the history, which were referred for forensic exam based on the anogenital alteration found. There were 39 cases (1.4%) of minors with a history of accidents (injury due to straddle position and other accidents), which present no material traces of sexual abuse.

Conclusion of the forensic report.

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual abuse cases confirmed by material evidence | 248 | 8 |

| Cases of non-specific traces | 601 | 21.4 |

| No traces upon physical examination | 1877 | 67.0 |

| Account of accident with no evidence of sexual abuse | 39 | 1.4 |

| Illness confused with sexual abuse | 31 | 1.1 |

| Other | 6 | 0.2 |

In the population we studied, most of the minors presented an account of sexual abuse. The disclosure of sexual abuse may have devastating effects on the family unit and it has therefore been said that there is a type of “pact of silence” between victims and aggressors.17 There are several reasons that sustain this pact of silence and hinder the disclosure of sexual abuse by the victims. In addition to the threats that many victims suffer from their aggressors, the disclosure of abuse can be extremely stressful for a minor. Many cases of sexual abuse are committed by parents or step-parents and the disclosure can imply prison for a family member with whom the victim has strong affective ties and who may be the financial support of the family unit.17 Thus, the cases who gave accounts of sexual abuse in the study population represent those who broke this pact of silence and were able to receive assistance from the police authorities. It is estimated, based on the studies conducted with questionnaires applied in adults, that more than 80% of the victims of child sexual abuse never disclose it,18 and the data collected by the services for the protection of minors represent less than 10% of the total cases of child sexual abuse.19

The increase in the number of forensic exams due to suspected child sexual abuse during the study period may have resulted both from the increase in the population from 3,021,572 to 3,573,973 between 2000 and 2010 with an 18.3% increase,14 as well as from the impact of awareness-raising campaigns about child sexual abuse.

The mean age of the presumed sexual abuse victims was 6.5 years. Given that verbal skills are important requisites for the minor to be able to share with someone an account of sexual abuse, those in the pre-verbal phase may have been less represented in the study population.

The 78.4% ratio for females among the minors examined due to suspected sexual abuse is in line with the data in the literature,12,13 although it has also been reported that boys are less likely to disclose sexual abuse.17

There was a predominance of minors originating from the municipality of Salvador (75.0%) and this reflects the weight of this municipality, which in the IBGE census of 2010 included 74.8% of the population of the metropolitan region.14 The interview with the child was part of the exam in 60.0% of cases and, in most of the forensic exams, the minor's words were not transcribed in the forensic report. This may be related to the priority given, in the forensic exams in the criminal sphere, to objective data from the physical examination.15

Among those aggressors with no family relationship with the minor, the proportion of strangers was 8.8% (92) which reinforces data referred to in the literature that family members and friends of the family constitute the greatest source of child sexual abuse.12,17

The time period between the event and the forensic exam was, on average, 96h, among those who were able to report the date of the abuse, and barely 25.0% of cases were examined within 24h of the abuse. Unlike minors who were victims of accidental genital trauma, the majority of whom are examined within 24h of the occurrence, the victims of sexual abuse usually disclose it later, decreasing the likelihood of the finding any injuries and the collection of forensic traces that may have existed.20

A relevant finding in this study was the high proportion of cases with an account of sexual abuse that showed no alterations in the physical examination. There may be various reasons for the absence of findings in a child who gives an account of sexual abuse. In the first place, it is important to consider that sexual abuse against a child includes forms without penetration, such as caressing and touching erogenous zones, and other forms of abuse that do not include physical contact. It is understood that it is typical for the abuser to practice libidinous acts which do not involve trauma due to misgivings about losing access to the victim.21 Secondly, even for forms of abuse that include penetration, or types of touching with ejaculation, the possibility of detecting the abuser's biological material on the victim's body may become impossible due to the short period of time that these traces remain.22 Thirdly, in the presence of genital or anal lesions, the studies have shown that such lesions heal quickly and, in general, without leaving traces, or leaving non-specific traces.23,24 Thus, in addition to the types of abuse that leave no traces, there is also a possibility that no physical evidence may be found due to the delay in time between the forensic exam and the sexual abuse, as occurred for the majority of cases in this research. Lastly, consideration must be given to the possibility of false accounts of sexual abuse. Nevertheless, currently, there is a consensus that false allegations made by children are rare.25,26 The position of dependence that the minor has with respect to the aggressor makes him or her unlikely to make up a false report. When the aggressor is a family member, especially a parent, there is the fear of rejection or of explicit or veiled threats, or fear of the separation of the parents. This is a situation of conflict and ambivalence because the perpetrator is not only an abuser, but is also, in many instances, the financial provider, and provider of many other things, such as affection and attention. Including when strangers are involved, there are feelings of shame and guilt, not to mention possible threats, which tend to prevent the abuse from being disclosed.25

In an investigation conducted by the child protection services in Canada with 798 accounts of sexual abuse, 6% were considered as intentionally false.27 In this series, there were no cases of false accounts made by a minor. Of the 576 minors investigated for sexual abuse, Jones and McGraw28 found 6% of false allegations made by parents, classified as intentional, and 2% by minors. Oates et al.,29 in 551 cases of accounts of sexual abuse, found 2.5% of false reports or false interpretation of sexual abuse coming from the minor.

The proportion of confirmed cases of sexual abuse based on material proof found in our study was greater than that reported in other investigations. Modelli et al.13 found 3.5% of cases confirmed in girls and 9.6% in boys examined in the legal medical institute of Brasilia (Brazil) for suspected sexual abuse. Heger et al.30 found 4% of cases of confirmed sexual abuse in a population of 2300 minors referred to sexual abuse reference centres in Los Angeles (USA).

The results of this study highlight the low sensitivity of forensic physical examinations for detecting sexual abuse. The diagnosis of sexual abuse is very dependent on the data provided in the clinical history;31 however, the forensic physical examination is understood as an attempt to obtain material evidence of a crime. Thus, the cases of sexual abuse confirmed by the forensic doctor in the completed study were limited to those that provided material proof. Nevertheless, the approach to victims of child sexual abuse requires a multidisciplinary team, including appropriate coordination between professionals in the clinical and social spheres, which goes beyond the individual work of the forensic doctor.32 Bearing in mind that the forensic reports are referred to the police and judicial authorities, who may not know the limitations of those exams, it is important that forensic doctors explain these limits when drawing up their reports. Otherwise, the frequent lack of traces may be interpreted as proof that no abuse occurred and serve to disqualify the interview, which is the only relevant data in most cases. This is most important in countries like Brazil, where the multidisciplinary assistance network for minor victims of sexual abuse is not yet consolidated, and where the forensic physical examinations have a predominant important role in evaluation, including in cases that are not recent.

As limitations, the authors used data existing in the forensic reports of forensic sexology and the variables studied were confined to those available in the reports. The cases in this study were examined by different forensic doctors and the criteria used in the evaluation may have lacked uniformity.

In conclusion, in the population studied, there were accounts of sexual abuse in 84.9% of cases and the proportion of cases of sexual abuse confirmed by material evidence was 8.9%.

In light of the infrequent occurrence of false accounts of sexual abuse given by minors that is described in the literature, this data shows the limitations of forensic sexology expertise to confirm sexual abuse in this age group. Thus, it is important that the forensic doctor specify these limits in the forensic report, so that the absence of findings on the physical examination is not interpreted by the authorities to whom such exams are directed as proof that there was no abuse, and consequently lead to the disqualification of the minor's accounts.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: dos Santos Silva W, de Oliveira Barroso-Júnior U. Características de los menores de 12 años con examen médico forense por sospecha de abuso sexual en Salvador, Brasil. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2016;42:55–61.