Advance Directives have been legally binding in Spain since the publication of Act 41/2002, of 14th November, which regulates patients’ rights to autonomy and obligations concerning clinical information and recording clinical information. However, the situation in each country of the European Union remains heterogeneous and unknown to most health care professionals.

By collecting and studying the legislation on patients' rights in European Union countries we have made an updated comparison of the different features of Advance Directives in each country.

Only 15 of the 28 European Union Countries have developed specific rules on advance directives which makes them legally binding in 86% of cases if they are written. A formal Advance Directive signed before a notary, a civil officer or a witness, is required in only 7 countries. The designation of a patient’s attorney for health matters is regulated in 11 of the countries. There is an Advance Directives Register in 3 countries, whereas in the other countries it is only included in the medical record. Regular revision of an advance directive document, to maintain its validity, is required in five countries. All legislations provide for amendments and the revocation of advance directives, as they forbid unlawful actions. Rejection of routine supportive measures and treatment limitation are the main content of advance directives, although specific treatment applications are viewed as guidance.

There seem to be many differences between laws concerning advance directives among the European Union Countries. A more homogeneous legislation, publicized and applied within the wider social consensus, would be desirable.

La Ley 41/2002, de 14 de noviembre, básica reguladora de la autonomía del paciente da valor legal vinculante a las Voluntades Anticipadas (VA) en España. Sin embargo, la situación en cada país de la Unión europea (UE) es distinta y desconocida para la mayoría del personal sanitario.

Para conocer esas diferencias, se realizó una recogida y estudio de las distintas legislaciones en materia de derechos del paciente, y se estableció una comparativa actualizada de las características que cada país otorga a las VA.

De los 28 países de la UE, 15 han desarrollado legislación específica en materia de VA, y le otorgan carácter vinculante el 86 % si se utiliza la formulación escrita. Siete países exigen formalización del documento de voluntades anticipadas (DVA) ante notario, testigos o ante representantes de la Administración. La figura del representante se contempla en 11 países. En 3 países existe un registro de VA, mientras que en el resto el DVA solo se incluye en la historia clínica. En 5 países se exige la revisión periódica del Documento, que pierde validez pasado este periodo de vigencia. Todas la legislaciones prevén modificaciones y la revocación de las VA. El contenido de la VA suele referirse al rechazo de medidas de soporte y limitación de tratamiento, aunque las solicitudes de tratamiento específico se contemplan como orientativas.

La legislación sobre VA en la Unión Europea es muy diversa, con múltiples connotaciones específicas en cada país. Sería deseable una legislación más homogénea, divulgada y aplicada, de acuerdo con la sociedad actual.

The living will document (LWD) arises from the need to respond to conflictive situations in which the decision has to be taken whether to maintain or withdraw life support measures, or to commence with interventions or procedures in patients who are unable to express their wishes.

At the end of the 1960s the first draft of a LWD was prepared, and it was known as a living will. Louis Kutner, a lawyer and activist in an association that campaigned for the right to a dignified death, created a document that was similar to a conventional will in which the maker of the will could give written evidence of the instructions regarding the medical interventions and care they wished to receive in the last days of their life. This document had to be created while the patient was considered competent.

One of the triggers for the development of documents of this type may have been the debate which arose due to the orders for non-resuscitation in a London hospital. These orders applied to elderly patients with chronic pathologies that were not controlled, and this led to the idea that some type of guide was necessary for medical personnel in situations of this type.1,2 It also started to become clear in the same decade that cardiopulmonary resuscitation could trigger new problems, and that sometimes life may be prolonged under conditions that were completely incompatible with personal dignity.1,3

Different initiatives subsequently tried to ensure patient autonomy. Perhaps the most important of these initiatives in Europe was the one which emerged at the end of the 1990s, the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and the Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine.2 Article 5 of the said Oviedo Convention states that, to be able to execute an intervention in the field of health, the previous and explicit consent of the person involved is indispensable; and also, article 9 refers to the need to respect the desires which patients have expressed. Other agreements have gone further into this question, such as the European Union Charter of Fundamental Rights4 (EU) (Nice, 2000), which became binding for EU countries after the Treaty of Lisbon (2007). Article 3 of this Treaty establishes the principle of patient autonomy, although it says nothing about their desires. Patient autonomy was thereby enhanced, and article 5 of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights was reaffirmed, having been approved in 2005 by the UNESCO General Assembly.5

In Spain, Law 41/2002 governs patient autonomy and the rights and obligations in terms of information and clinical documentation. It covers aspects such as the right to information and to accept or reject different treatments and the limitation of therapeutic effort, etc. Moreover, the different regulations of the autonomous communities have made it possible to develop and implement this law in an attempt to improve the patient-doctor relationship and to clarify difficult situations, such as end-of-life care.6

In the U.S.A. the field of palliative treatments and end-of-life care has undergone great development over the past 20 years. Doctor training and their relationship with patients now emphasise that both parties should take part in decision-making, so that if a patient does not wish to receive a certain treatment to prolong their life, this decision must be respected.

However, in everyday practice few studies have shown that the application of living wills (LW) has been successful. Teno et al. reviewed almost 700 living wills and found that more than half did not include the clinical history of the patients, making them documents which would be of very little use if the doctor in question lacked this information.7

Legislation governing LW in different EU countries differs widely in form as well as in content. In fact, the existence of a shared legislative framework which is backed by the Council of Europe has not prevented each country from behaving differently in this field, due to cultural and religious factors among others.8

This variability gives rise to a heterogeneous situation that is both hard to describe and increasingly important due to the increasing professional mobility of doctors within the EU, so that they may face situations of this type in different legal circumstances. The aim of this study is therefore to establish an updated picture of the situation of LW and the existing legal framework for them within the EU.

ObjectivesOur main objective was to make a comparison current law in the 28 countries of the EU in connection with LW and LWD, so that the legislation in each country can be evaluated.

Our secondary objectives were to establish points for reflection on the actual situation of LW and LWD, as well as to establish possible points for improvement within the current legislative framework.

MethodologyFirstly the current laws in Spain were compiled. They are considered by legal and legal medicine experts to be among the most complete and exhaustive of the comparable laws in neighbouring countries (Law 41/2002, of 14 November, the basic law regulating patient autonomy and rights and obligations in terms of information and clinical documentation. There is also Royal Decree 124/2007, of 2 February, which governs the National Registry of Previous Instructions and the corresponding computer file containing personal data).

The main characteristics of these laws may be summarised by the following points:

- a

They are specifically about LWs (2002) and created the LW registry (2007).

- b

This law is binding, i.e., it has to be obeyed.

- c

To be legally valid, LWs must be expressed in writing, in the LWD.

- d

The formalisation of the LWD is specified: it must be drawn up before at least three witnesses, who have to sign the document. It may also be notarised. In up to 10 autonomous communities it may also be formalised before a representative of the Administration.

- e

A representative may be designated who solely has the power to take the health decisions which are best for the patient according to the guidelines of their LW.

- f

It considers the possibility of a centralised registry with the aim of facilitating access to an LWD by medical personnel from any part of the country, regardless of the autonomous community where it was issued.

- g

It stipulates who is able to access the document once patients are in a situation in which they are unable to take decisions for themselves.

- h

It neither demands that the document be regularly revised, and nor does it set any time lime after which the document becomes invalid.

- i

It allows documents to be modified at any time, on condition that the guidelines set out above are followed, that the modification is registered and that a new version is sent.

- j

It permits the maker to revoke the LW at any time.

- k

It restricts the guidelines which the document may express, nullifying those which go against current law and forbidding active euthanasia.

On the other hand, a search and collection was made of laws currently in force in this field of the Council of Europe (ETS No. 164. Convention for the protection of the Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine; Recommendation CM/Rec (2009)11 of the Committee of Ministers to members states on principles concerning continuing powers of attorney and advance directives for incapacity; Resolution 1859 (2012) and Recommendation 1993 (2012) of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe: Protecting human rights and dignity by taking into account previously expressed wishes of patients).

A search was also conducted for the laws of the European countries within the EU: Germany, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Denmark, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, the United Kingdom, the Czech Republic, Rumania and Sweden.

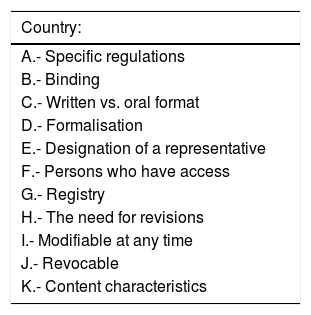

Once all of this information had been collected, and following the quality criteria for Spanish law, we drew up a comparative table to show the laws of the different European countries so that they could be analysed (Table 1).

Characteristics of Spanish law, which will serve as the basis for comparing different legal systems.

| Country: |

|---|

| A.- Specific regulations |

| B.- Binding |

| C.- Written vs. oral format |

| D.- Formalisation |

| E.- Designation of a representative |

| F.- Persons who have access |

| G.- Registry |

| H.- The need for revisions |

| I.- Modifiable at any time |

| J.- Revocable |

| K.- Content characteristics |

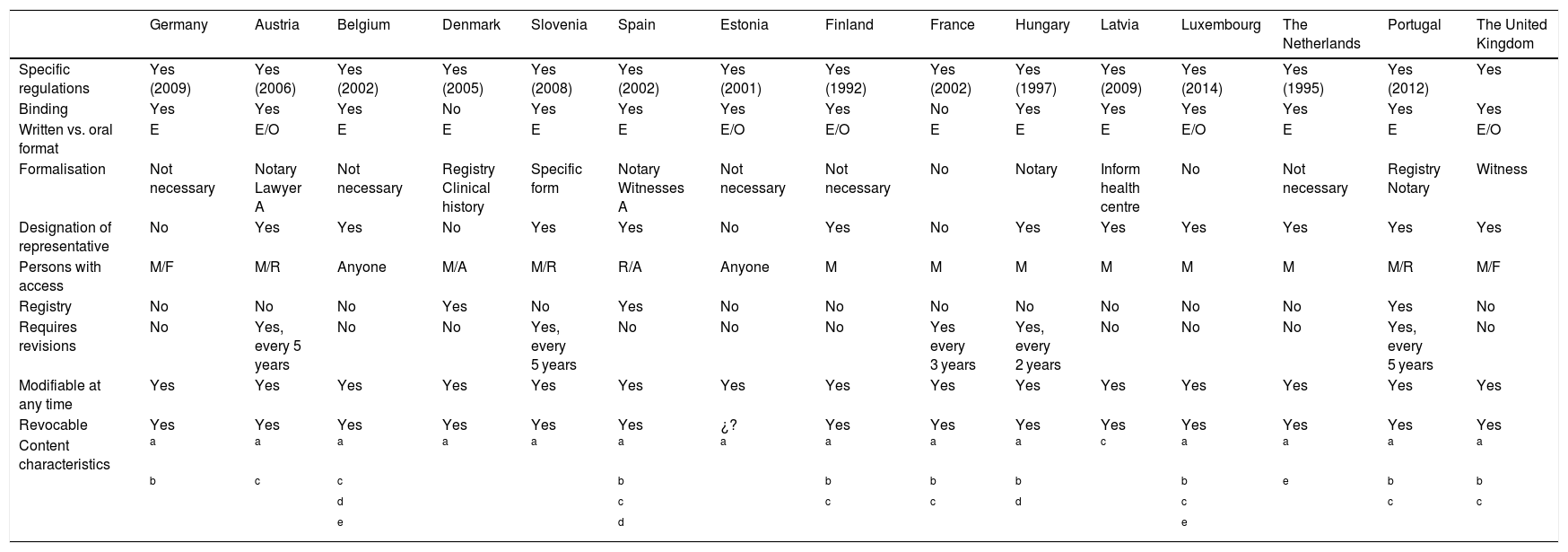

We express the results of the analysis by specifying each section of the comparative table described above (Table 2):

- A

The existence of a specific law on LWs.

Characteristics of European Union countries’ legal systems in the field of previously expressed wishes.

| Germany | Austria | Belgium | Denmark | Slovenia | Spain | Estonia | Finland | France | Hungary | Latvia | Luxembourg | The Netherlands | Portugal | The United Kingdom | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific regulations | Yes (2009) | Yes (2006) | Yes (2002) | Yes (2005) | Yes (2008) | Yes (2002) | Yes (2001) | Yes (1992) | Yes (2002) | Yes (1997) | Yes (2009) | Yes (2014) | Yes (1995) | Yes (2012) | Yes |

| Binding | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Written vs. oral format | E | E/O | E | E | E | E | E/O | E/O | E | E | E | E/O | E | E | E/O |

| Formalisation | Not necessary | Notary Lawyer A | Not necessary | Registry Clinical history | Specific form | Notary Witnesses A | Not necessary | Not necessary | No | Notary | Inform health centre | No | Not necessary | Registry Notary | Witness |

| Designation of representative | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Persons with access | M/F | M/R | Anyone | M/A | M/R | R/A | Anyone | M | M | M | M | M | M | M/R | M/F |

| Registry | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Requires revisions | No | Yes, every 5 years | No | No | Yes, every 5 years | No | No | No | Yes every 3 years | Yes, every 2 years | No | No | No | Yes, every 5 years | No |

| Modifiable at any time | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Revocable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ¿? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Content characteristics | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | c | a | a | a | a |

| b | c | c | b | b | b | b | b | e | b | b | |||||

| d | c | c | c | d | c | c | c | ||||||||

| e | d | e |

In Hungary the content expresses the wish NOT to donate organs.

A: administration personnel; E: written; F: family member; M: doctor in charge or medical personnel; O: oral; R: representative.

Of the 28 countries of the EU, only 15 have specific law covering LWs. Of these countries, the majority have ratified the Oviedo Convention. Only 5 countries have neither developed laws on LWs nor have ratified the Oviedo Convention (Ireland, Italy, Malta, Poland and Sweden).

- B

Binding legislation.

Almost all of the countries with specific laws make them legally binding, except for Denmark and France, in which the law is solely a guideline for decision-making.

- C

Expressed in writing.

In general written expression is selected as the valid form, except in Finland and Estonia, where an oral expression is also valid.

- D

Formalisation.

This differs depending on the country. It may take place before a notary, before several witnesses or before the Administration, or it may not have a specific form (the patient herself or her representative usually informs the doctor about a LW).

- E

Designation of a representative.

The designation of a representative in the field of health is considered in 11 countries, and this may be included in the LWD or not, or in another parallel document, depending on the country. Four countries (Germany, France, Denmark and Estonia) do not consider the designation of a representative.

- F

Access to the LWD.

Only 3 countries have a LWD registry (Denmark, Spain and Portugal). The LW is only shown in the patient’s clinical history in the other countries.

- G

LW registration.

This is one of the most ambiguous points in the different legal systems, as it is not explicitly said who can access this information. It is understood that the doctor in charge can, together with his legal representative in those cases where this figure exists.

- H

Regular revisions.

Regular revision of a LW is only recommended in 5 countries, although they do not set a specific time limit for this. It is understood in the other countries that LWs must be expressed as recently as possible, so that they fit the actual situation of the patient.

- I

LW modification.

All of the countries permit the possible modification of LWs at any time.

- J

Revocation of LWs.

It is possible to revoke a LW in all of the countries, either in writing or orally, although it is usually recommended that a written record of this be left.

- K

Content characteristics.

In general, the LWD contains the desire for treatment to be limited in specific health situations. In Denmark and Finland it is even possible to include lifestyle preferences and personal tastes in clothing, food and music … The wish for a certain drug to be administered when this is not considered to be indicated by the medical team is rejected. Only Belgium and Spain consider the possibility of specifying the destination of bodily organs and the body itself in the LWD; while in Hungary the LWD can be used to reject organ donation.

The subject of active euthanasia is more controversial, and it is only considered legal in 3 countries (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands). This subject occupies a separate and different space in law, and it is covered by a document other than LWs.

DiscussionAlthough the General Health Law emphasised the principle of autonomy, it did not cover LWs. Nevertheless, signing of the Oviedo Convention stimulated lawmakers’ interest in this subject in Europe and most particularly in Spain, which can be proud of its complete and ambitious law, even though it may also be criticised for many reasons.3,9 Even so, there are clear differences between the countries of the EU, due to cultural, religious and legislative factors.

Respecting the signing of the Oviedo Convention, it has to be underlined that not all EU countries have adopted it, even though it is one of the most important 5 documents in connection with human rights at world level. Not having ratified this convention does not mean that the countries in question have no laws governing this field. In fact, some are countries which are highly active in support of patient rights, such as Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, which have even legislated in favour of euthanasia.10–12 The important thing in any case is that Oviedo Convention guidelines must be applicable in any country which has ratified it. However, this is still not the case as there is no agreement among the different countries on how to understand and accept the scope of the document.13

The binding nature of the LWD means that it has legal validity and must therefore be respected. Nevertheless, the way in which it is considered to be binding differs and may be understood in different ways, depending on each country. In Denmark and Slovenia it is considered to be a guideline document that is only binding in the case of inevitable imminent death14; in France it has not been endorsed as binding15; in Germany and the Netherlands all of the conditions have to be met exactly if it is to be binding16,17; in Austria is has to be signed before a notary, while in the United Kingdom more emphasis is place on the criterion of the medical team if there is any evident and well-reasoned justification for this.18

As to whether the format of the LWD is written or oral, the majority of countries opt for a written format. Only Finland and Latvia accept an oral expression of wishes, although their laws are somewhat vague and leave doubts about the validity of this format. In any case it would seem prudent for there to be a document which expresses last wishes, above all in case of conflict, although we should not allow ourselves to be restricted to a rigid procedures, as we should know how to adapt to each case.

The formalisation of the LWD is usually a complex administrative procedure that also varies from one country to another. In Spain the signature of a notary or those of 3 witnesses with no family or contractual relationship is required. Some autonomous communities also accept the signature of a representative of the Administration (as is also the case in some European countries). In general these 3 possibilities are the most widespread in different European legal systems. Formalisation in Austria19 is usually complicated (as it requires the expert assessment of the person who issues the LWD, which then has to be presented before a notary, lawyer or representative of the administration, and fees also have to be paid). In Hungary20 the process is similar, as it requires assessment by a doctor, a specialist in the field and a psychiatrist. Other countries require no specific procedure, so that it is the patient and their family members or those close to them who give inform the doctor of the LW. Another interesting option would be to include the LWD as a part of the clinical history, as this would create the possibility of managing the process while seeking the best possible care for the patient, who would take the decisions on his future after receiving information, absorbing it and thinking about it.21

The designation of a representative is one of the key points, although their powers may vary between countries. We can find some legal systems which opt for the creation of the figure of the representative, with more or less opportunity for family members to offer informal representation, and of course with the possibility of granting the medical team the power to take certain decisions at certain times. In Spain, Portugal, Luxembourg and the Netherlands the representative functions as the interlocutor with the medical team to interpret the LW and ensure that it is taken into account in the decision-making process.22 This form of representation is restricted to the field of health and sickness, and it only functions when the patient is unable to express their wishes. No other document is usually necessary to formalise such representation, and the representative is usually designated in the LWD itself, thereby speeding up the procedure. In Denmark, Germany, Estonia and France the function of the representative is not restricted to the field of health, as they are able to facilitate decision-making in all aspects of life. This is so in part because of the activism of associations which support patients with degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s.23 In France the patient is able to designate a trusted individual (personne de confiance), who would be able to assist the patient in decision-making, receiving information from the medical team and informing them of the patient’s wishes. However, this individual has no legal power to take decisions.15 In the United Kingdom designating a representative involves a specific procedure18 and generates a new document. The Office of the Public Representative also has to be notified in a document which sets out the limits to the decisions that the representative is able to take. They also establish which considerations the representative must take into account when taking decisions, seeking the best interests of the represented individual and thereby supporting substituted judgement.24 Austria permits representation by family members or trusted individuals, on condition that they are inscribed in a specific registry.25 Belgium, Slovenia, Finland and Hungary require the formalisation of a parallel document for an individual to be a representative. Informal representation by family members is possible in the absence of such a document.26,27

Another important aspect is the creation of a LW Registry, to facilitate access by medical personnel to guarantee care for a person in any geographical location.28 As well as using this Registry, medical personnel may also receive a patient’s LW if anyone or the patient himself supplies a correctly completed and validated copy of the same. The existence of the Registry has another possible advantage associated with the privacy of the process, as some people prefer to perform this process more confidentially. This aspect is only possible in the EU in Spain, Portugal and Denmark, and only the first two of these countries have a working Registry. Access to this information is granted to the signer, their representative and the medical team.

A LWD may change over time, depending on the clinical circumstances of the patient. It is true that regular revision of a LWD would be ideal to ensure it expresses the will of the maker according to their situation. This would make the document less vague, which is the basis for one of the most important criticisms in all of the European laws.29 A time limit is usually set for the validity of the document (for example, Hungary and France demand that it be renewed every 2–3 years). However, these LWs should be taken into account as a guideline when decision-making, as they express the preferences of the patient with more or less validity, depending on how much time has passed since they had to be renewed.

With regard to modifications of the content of a LWD, all of the countries stipulate that this may occur at any time, generating a new document which replaces the previous one. A LWD may also be revoked at any time, without setting any formal requisites (a written format for this is only required in Slovenia and Luxembourg). The possibility of revocation would prevent the possibility that outdated and unwanted LW would not be applied when the patient has changed their mind. Nevertheless, there is a delicate situation which may arise when the family member of an unconscious patient suggests that the maker of a LW may have retracted it, which would invalidate it, thereby creating possible vulnerability of the maker’s rights.

The content of a LWD usually refers to the patient’s desire not to be subjected to examinations or treatments if they are in a circumstance caused by disease which they regard as unacceptable. However, as the document is open, other wishes may also be expressed. These may cover palliative treatments or general aspects of care (for example, in Finland it covers types of clothing and food, together with tastes in music …), or organ donation and the final destination of the body. Once again, Spanish law30 is the most ambitious in terms of its content.

As the document is drawn up freely, it may contain a request for active euthanasia or assisted suicide. This procedure is prohibited in the majority of countries in the EU and it is considered to be a criminal offence. Thus requests for treatments that are against the law would also be annulled. Only Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands10,12 admit the possibility of active euthanasia, although this is governed by different laws and is expressed in a different document.

Our review found that to date somewhat more than half of EU countries have developed specific law in this field, and that the heterogeneous nature of the law makes it hard to put into practice. This aspect is also true of the 13 countries which have yet to pass their own laws, as their situation too is not uniform. Some of these countries (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Slovakia, Greece, Lithuania, the Czech Republic and Rumania) have ratified the Oviedo Convention, so that its article 9 on patient desires expressed beforehand should be binding. Increasing numbers of groups in these countries (including medical professionals) support improving the healthcare system, including the protection of patients’ rights.31,32 On the other hand, there is also variation among the countries which have not ratified the Oviedo Convention. Although Italy and Ireland are in the process of passing a law on wishes expressed beforehand,33,34 this is a long procedure due to the lack of social agreement. In Poland the overlapping nature of concepts such as LW and passive and active euthanasia means that the law has to identify and treat each circumstance individually.35

ConclusionsAfter reviewing the laws on LW within the EU we found that unfortunately there is a low rate of LWD formalisation. Moreover, few data are available in each country, as there are usually no official Registries to record how far this practice has become widespread in society.

As there is a Registry in each autonomous community in Spain, together with a Central Registry that centralises their data, this facilitates data gathering here. In April 2015 the total number of inscribed documents amounted to 185,665, corresponding to a rate of 3.97°/00.

It is true that not all LWD are recorded in a Registry, and that determining the number of documents which have been issued at European level is especially difficult.

The characteristics of content and formalisation differ depending on the country in question, so that medical professionals who travel to another country should have accessible and clear sources of information so that they can clarify any doubts which may arise in their everyday clinical work. Another aspect that should be underlined is the lack of awareness and acceptance of LW within the world of medical professionals, where a high percentage of doctors state that they know nothing about the LWD.

Finally, although the LWD has clear advantages for the doctor-patient relationship, it has not been introduced uniformly due to social, religious and political considerations. A single European law would be desirable in this field, to facilitate doctors’ working and guarantee the principle of patient autonomy. We are still a long way from the ideal situation; but even so, we found increasing concern in our neighbouring countries for patient care while respecting their right to express their wishes.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Porcar Rodado E, Peral Sanchez D, Gisbert Grifo M. El documento de voluntades anticipadas. Comparativa de la legislación actual en el marco de la Unión Europea. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2021;47:66–73.