The aim of this clinical practice guideline is to provide a rationale for the implementation of the Zero Delirium Project (ZDP) - a series of recommendations for patients in special critical care units (SCCU). The recommendations were developed by a group of anaesthesiologists from around Spain, and were reviewed by the Scientific Committee of the Spanish Society of Anaesthesiology, Resuscitation and Pain Therapy. Delirium is an acute, fluctuating, multifactorial syndrome characterised by inattention, disorganised thinking, and an altered level of consciousness. It may affect up to 56% in patients during their stay in critical care, and is important because many SCCUs have not yet introduced routine delirium screening, treatment and prevention strategies. Staff that are able to recognise and diagnose delirium can prevent it, treat it and reduce its incidence, which in turn reduces morbidity, mortality and costs. The ZDP was created with this aim in mind.

El objetivo de la presente guía clínica es proporcionar una base racional de práctica clínica para implementar una serie de recomendaciones en pacientes en Unidades Especiales de Cuidados Criticos (UECC) mediante el Proyecto Delirium Zero (PDZ). El grupo elaborador de las recomendaciones estuvo formado por médicos especialistas en Anestesiología y Reanimación de diferentes áreas del territorio nacional, y fue revisada por el Comité Científico de la Sociedad Española de 2_eliminar las referencias bibliográficas Anestesiología Reanimación y Terapéutica del Dolor.

El delirium es un síndrome caracterizado por una alteración aguda y fluctuante del nivel de conciencia y de la capacidad cognitiva, de causa multifactorial, y que puede alcanzar una incidencia de hasta el 56% en los pacientes durante su estancia en UECC. La importancia de este síndrome radica en que gran parte del personal sanitario que atiende a pacientes en UECC todavía no ha incorporado medidas rutinarias para el diagnóstico, la prevención y el tratamiento del delirium. Conocerlo y diagnosticarlo ayuda a prevenirlo, a tratarlo y a disminuir su incidencia, con lo que a su vez descienden la morbilidad, la mortalidad y los costes. Con esta finalidad nace el Proyecto Delirum Zero.

Delirium is an acute, fluctuating, multifactorial syndrome characterised by inattention, disorganised thinking, and an altered level of consciousness. It may be accompanied by short-term memory dysfunction, attention deficit disorder, and disorientation.1,2 According to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-IV),3 the criteria for diagnosing delirium are as follows:

- A

Disturbance of consciousness (i.e., reduced clarity of awareness of the surroundings) with reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention.

- B

A change in cognition (such as memory deficit, disorientation, language disturbance) or the development of a perceptual disturbance that is not better accounted for by a pre-existing, established, or evolving dementia.

- C

The disturbance develops over a short period of time (usually hours to days) and tends to fluctuate over the course of the day.

- D

There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is caused by the direct physiological consequences of a general medical condition.

The fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-V) published in 20137 includes the criterion of disturbance in attention, and states that delirium is not a results of a pre-existing, established or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal such as coma. Delirium can be considered an acute brain failure and, like heart failure, is the common end result of multiple mechanisms.4 The cause is multifactorial, and includes serious pathologies, intoxication or withdrawal. The syndrome includes sepsis-induced encephalopathy, alcohol withdrawal syndrome, and hepatic encephalopathy.5

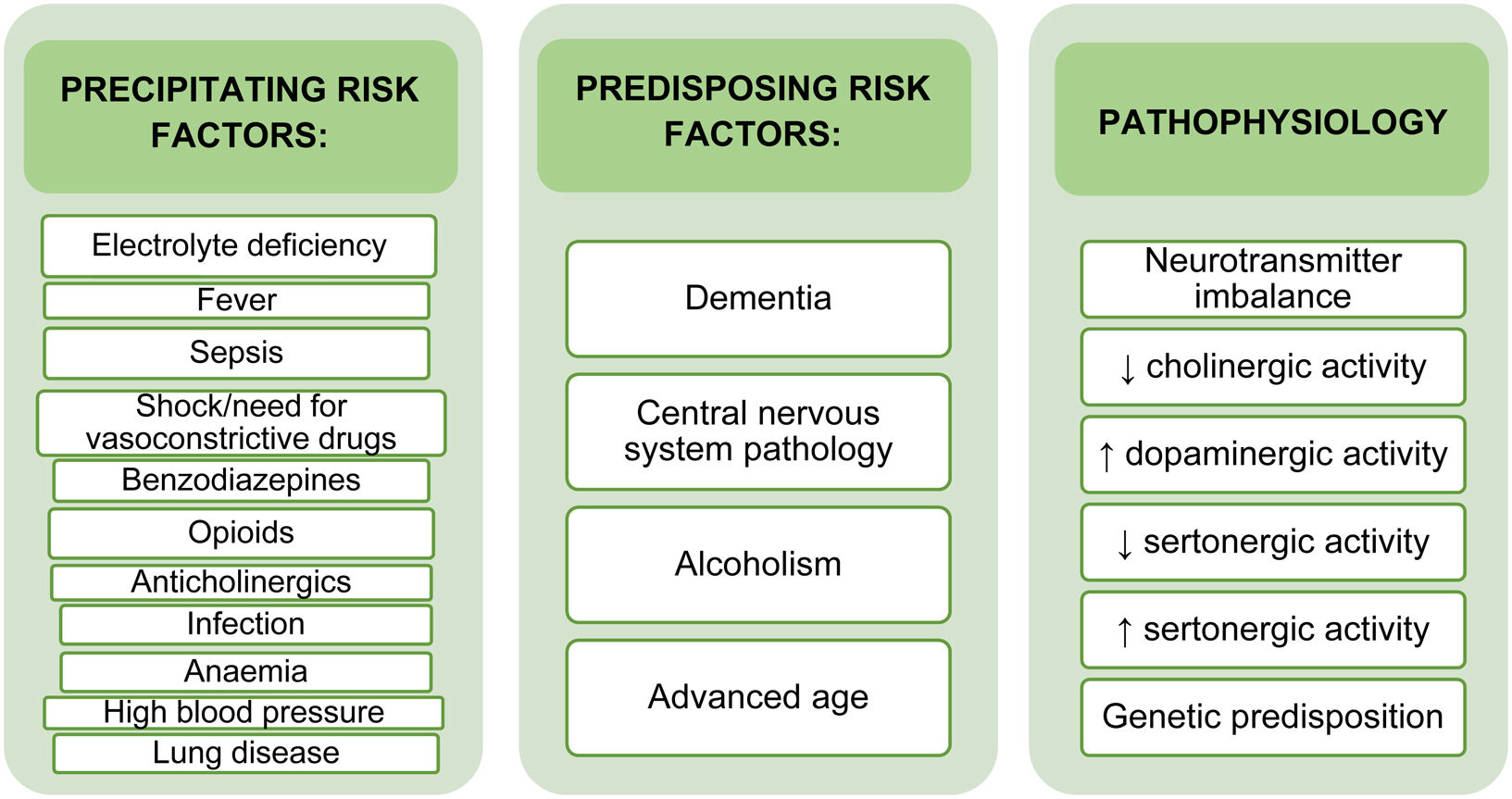

The cause of delirium is multifactorial. The prevailing hypotheses on the pathogenesis of delirium focus on the role of neurotransmitters, inflammation, and chronic stress, which converge in a cholinergic deficit coupled with elevated dopamine.6,7 The development of delirium is also influenced by predisposing and precipitating risk factors (Fig. 1). Predisposing factors include advanced age, previous cognitive impairment, and alcoholism. These factors are entirely patient-related and are rarely modifiable. Precipitating factors are potentially modifiable, and include treatment with benzodiazepines, prolonged stay and intubation in the ICU, immobilization, invasive monitoring catheters, noise and light levels that disrupt sleep patterns, etc. Early identification of modifiable factors can mitigate their impact on patient outcomes and prevent and reduce the incidence of delirium.8

The prevalence of delirium at hospital admission ranges from 14% to 24%, and can occur during hospitalization in as many as 56% of patients.9,10 The incidence of delirium in patients over 65 years of age who are admitted for surgery is between 15% and 25%. Postoperative delirium (POD) usually occurs within the first 3 postoperative days,11 and incidence varies depending on the type of surgery performed. Recent meta-analyses have shown that the incidence of delirium among patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery ranges from 15% to 35%,12 and from 5.8% to 45.8% in patients undergoing heart surgery13,14 The incidence of delirium in patients admitted to a critical care unit generally ranges from 11% to 87%.15

Delirium can be classified as hyperactive (agitation and motor activity predominate), hypoactive, or mixed, depending on the patient’s level of consciousness and psychomotor activity.16–19 Hypoactive delirium is characterized by attention deficit, altered thinking, and decreased level of consciousness without agitation. This type of delirium can be overlooked, and therefore has a worse prognosis.20,21 In ICUs, hyperactive delirium accounts for less than 2% of cases, hypoactive for 35%, and the most frequent type is mixed delirium, which occurs in 64% of patients.22

POD is associated with worse outcomes, a higher incidence of complications, prolonged mechanical ventilation, increased length of stay in the ICU and on the ward, increased readmission rates, and therefore higher healthcare costs. In the long term, it is also associated with impaired cognitive function, decreased physical capacity and quality of life, and increased mortality after discharge.11,14,23

Delirium is an important syndrome, because many special critical care units (SCCU) have not yet introduced routine delirium screening and strategies to treat and prevent this syndrome. Staff that are able to recognise and diagnose delirium can prevent it, treat it and reduce its incidence, which in turn reduces morbidity, mortality and costs. The Zero Delirium Project (ZDP) was created with this aim in mind.

Definition of the projectPopulation ageing is leading to a disproportionate number of frail, multimorbid patients requiring care in a public health system that is geared towards treating specific diseases. Two-thirds of hospital beds are occupied by patients aged over 65, and up to half of these patients have cognitive impairments such as dementia or delirium - circumstances that are particularly important in patients scheduled for surgical interventions, since they will often require care in Special Critical Care Units (SCCU) such as an intensive care unit (ICU) or a postoperative intensive care unit (PICU).

The neurocognitive impairment typical of delirium is associated with symptoms and communication difficulties that cause considerable stress to both the patient and their family. Delirium in SCCU patients is associated with increased morbidity and mortality1 and is sometimes under-diagnosed.2,3

Main objectiveThe aim of these clinical practice guidelines is to implement the Delirium Zero Project (DZP) - a series of recommendations for patients admitted to SCCUs.

Secondary objectivesThe aim of the DZP is to reduce both the incidence and complications of delirium by improving early diagnosis and prevention measures and guiding healthcare professionals in the treatment of delirium in adult patients in SCCUs.

MethodologyThe recommendations were developed by a panel of anaesthesiologists from around Spain and reviewed by the Scientific Committee of the Spanish Society of Anaesthesiology, Resuscitation and Pain Therapy.

The quality of the clinical practice guidelines was assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) document. PubMed, the Cochrane library, Scopus, the ISI Web of Knowledge, and Embase were searched to identify narrative and systematic reviews, editorials, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCT), cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies published up to 2023 that could be used to develop evidence-based recommendations on delirium (the flowcharts are available in the Supplementary Material).

Data from this systematic review were used to develop clinical recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of postoperative delirium for physicians involved in the perioperative care of adult patients. While the recommendations reflect current best practices, they are not intended to replace the physician's decision-making ability when presented with patient-specific clinical variables.

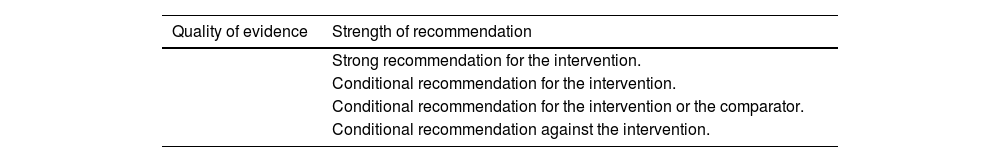

Each recommendation is classified according to its strength of recommendation and the certainty, or quality, of the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system. (Table 1) In the GRADE system, the quality of evidence reflects the extent to which an expert panel’s confidence in an estimate of the effect is adequate to support a particular recommendation. The strength of recommendations is based not only on the quality of the evidence, but also on a series of factors such as the risk/benefit balance, values and preferences of the patients and professionals, and the use of resources or costs. In all statements, strong recommendations are preceded by "we recommend" and conditional recommendations by "we suggest".

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system.

| Quality of evidence | Strength of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Strong recommendation for the intervention. | |

| Conditional recommendation for the intervention. | |

| Conditional recommendation for the intervention or the comparator. | |

| Conditional recommendation against the intervention. |

| Recommendation 1. We recommend using delirium screening tools in all patients on a daily basis or in the event of changes in cognitive status. We recommend administering scales validated for use in SCCUs: the CAM-ICU (and its variants: the 3D-CAM and the CAM-ICU-7), which is the gold standard, and the ICDSC in adults.2,27,34,35,37Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong 2. We recommend administering the DRS-R-98 or CTD scales to assess the severity of delirium symptoms.33,38Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Strong 3. We recommend administering the CDR or AD8 scales to promptly identify and diagnose delirium in patients with a history of dementia39Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Strong 4. We recommend that nursing staff administer the Delirium-O-meter, Nu-DESC or 4AT scales to screen patients prior to a medical diagnosis.29,40,41Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Strong 5. In adults with suspected delirium, we suggest performing platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and EEG wave analyses to identify delirium before administering validated scales to confirm the diagnosis.15,43Quality of evidence: Low Strength of recommendation: Conditional |

The detection of delirium in SCCUs is based on the administration of specific diagnostic scales. Failure to routinely administer these scales in clinical practice has led directly to the under-diagnosis of this syndrome,24 and training SCCU staff to administer validated scales will improve diagnosis of delirium and can reduce the number of cases by up to 60%.25

The gold standard diagnostic scale is the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU), followed by the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC). Up to 95% of delirium cases are diagnosed with one of these scales26:

- -

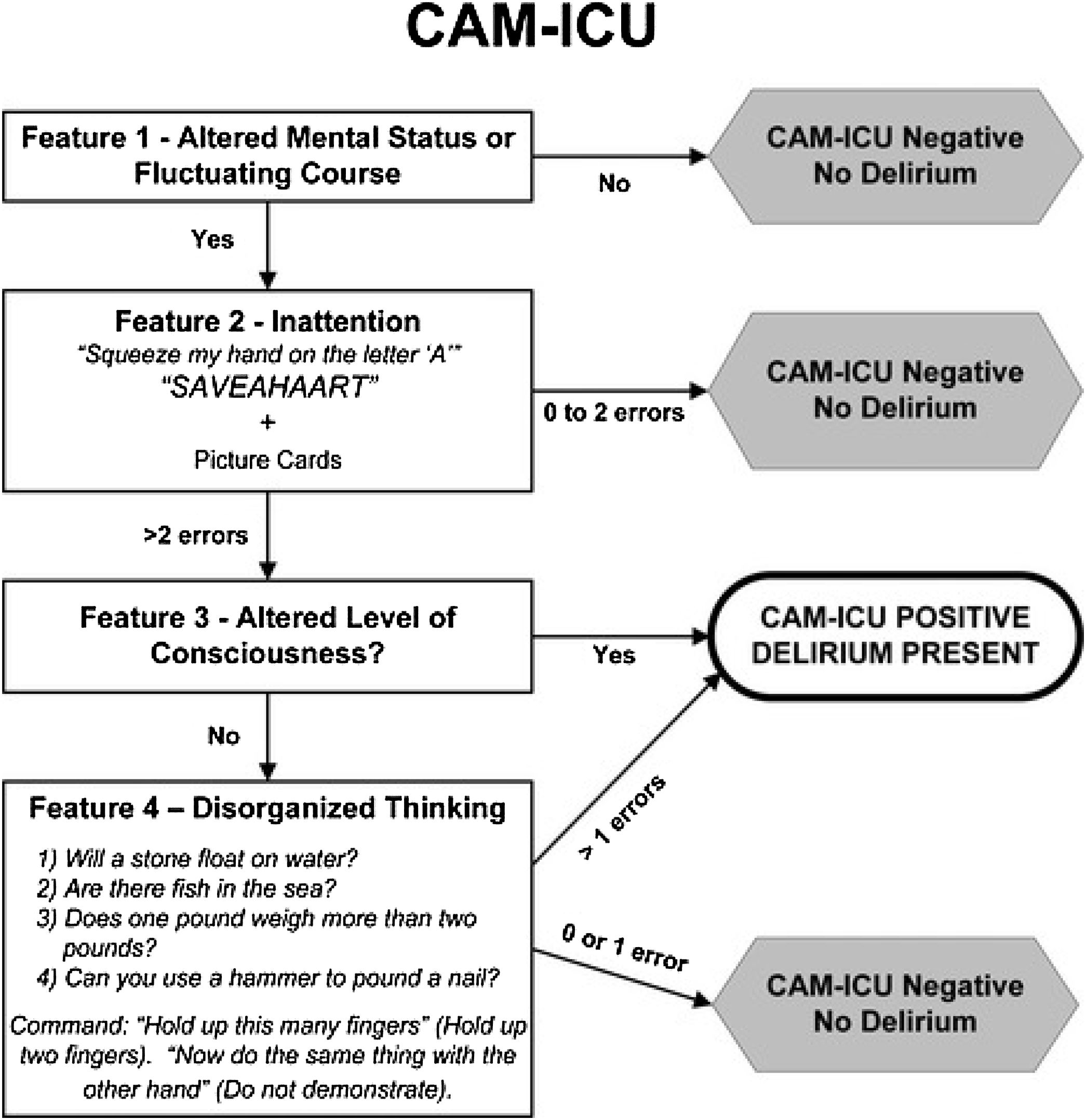

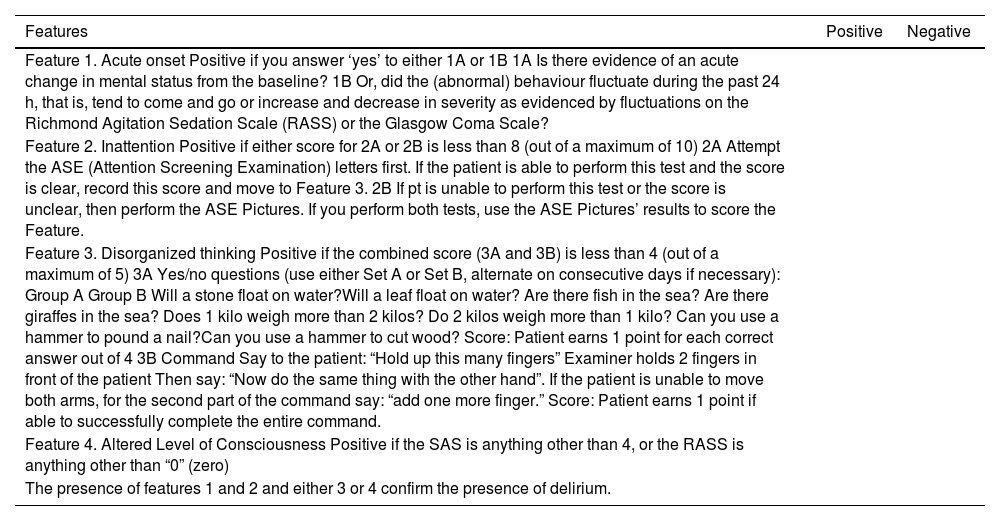

The CAM-ICU can be administered by nurses or doctors in 3−5 min to obtain a rapid diagnosis of delirium, and has also been validated for the diagnosis of delirium in critically ill and even mechanically ventilated patients who are momentarily unable to speak.27,28 It has a sensitivity of 97%, a specificity of 98%, and high inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.92−0.99).29 The CAM-ICU assesses 4 features of delirium: acute onset or fluctuating course, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness (Table 2, and Fig. 2). The test is positive if features 1 and 2 and either feature 3 or 4 is present. Before administering this scale in critically ill patients their level of state of sedation must be assessed using Riker’s Sedation Agitation Scale (SAS)30 (Table 3) or the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS)31 (Table 4). The aim of sedation scales is to differentiate hyperactive delirium (RASS score of +1 to +4) from hypoactive (RASS score of −3 to 0) or mixed (a positive, neutral or negative RASS result) delirium.32 The CAM-ICU scale cannot be administered in coma patients or in those under deep sedation (RASS score of −4 or −5).33

Table 2.CAM-ICU (this scale has been adapted and validated in Spanish).

Features Positive Negative Feature 1. Acute onset Positive if you answer ‘yes’ to either 1A or 1B 1A Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the baseline? 1B Or, did the (abnormal) behaviour fluctuate during the past 24 h, that is, tend to come and go or increase and decrease in severity as evidenced by fluctuations on the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) or the Glasgow Coma Scale? Feature 2. Inattention Positive if either score for 2A or 2B is less than 8 (out of a maximum of 10) 2A Attempt the ASE (Attention Screening Examination) letters first. If the patient is able to perform this test and the score is clear, record this score and move to Feature 3. 2B If pt is unable to perform this test or the score is unclear, then perform the ASE Pictures. If you perform both tests, use the ASE Pictures’ results to score the Feature. Feature 3. Disorganized thinking Positive if the combined score (3A and 3B) is less than 4 (out of a maximum of 5) 3A Yes/no questions (use either Set A or Set B, alternate on consecutive days if necessary): Group A Group B Will a stone float on water?Will a leaf float on water? Are there fish in the sea? Are there giraffes in the sea? Does 1 kilo weigh more than 2 kilos? Do 2 kilos weigh more than 1 kilo? Can you use a hammer to pound a nail?Can you use a hammer to cut wood? Score: Patient earns 1 point for each correct answer out of 4 3B Command Say to the patient: “Hold up this many fingers” Examiner holds 2 fingers in front of the patient Then say: “Now do the same thing with the other hand”. If the patient is unable to move both arms, for the second part of the command say: “add one more finger.” Score: Patient earns 1 point if able to successfully complete the entire command. Feature 4. Altered Level of Consciousness Positive if the SAS is anything other than 4, or the RASS is anything other than “0” (zero) The presence of features 1 and 2 and either 3 or 4 confirm the presence of delirium. Reference Tobar et al.151.

Table 3.Sedation-agitation scale.

Sedation-Agitation Scale (SAS) Unarousable Minimal or no response to noxious stimuli, does not communicate or follow commands. Very sedated Arouses to physical stimuli but does not communicate or follow commands, may move spontaneously. Sedated Difficult to arouse but awakens to verbal stimuli or gentle shaking, follows simple commands but drifts off again. Calm and cooperative Calm, easily arousable, follows commands. Agitated Anxious or physically agitated, calms to verbal instructions. Very agitated Requiring restraint and frequent verbal reminding of limits, biting ETT. Dangerous agitation Pulling at ET tube, trying to remove catheters, climbing over bedrail, striking at staff, thrashing side-to-side. Reference Riker et al.30

Table 4.Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS).

RASS SCALE Score Classification Description +4 Combative Combative, violent, danger to staff +3 Very agitated Pulls or removes tube(s) or catheters; aggressive +2 Agitated Frequent non-purposeful movement, fights ventilator +1 Restless Anxious, apprehensive, but not aggressive 0 Alert and calm −1 Drowsy Not fully alert, but has sustained wakening (more than 10 seconds) −2 Light sedation Briefly awakens to voice (eye opening/contact) <10 seconds −3 Moderate sedation Moderate sedation; movement or eye opening. No eye contact −4 Deep sedation No response to voice, but movement or eye opening to physical stimulation −5 Unarousable No response to voice or physical stimulation Reference Ely et al.31.

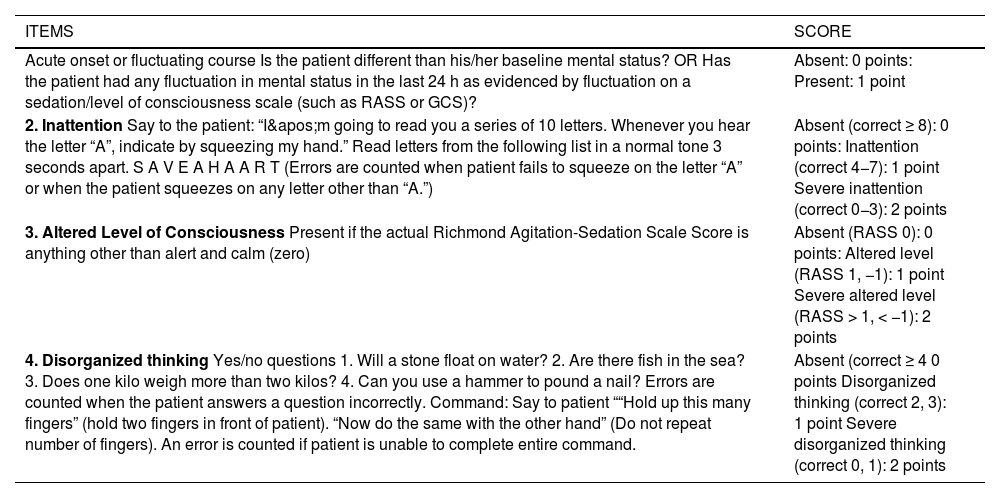

A number of variants of the original CAM-ICU have been developed, such as the 3-Minute Diagnostic Interview for CAM-Defined Delirium (3D-CAM) (Fig. 3), which is a short (3-minute) version of the CAM that has a sensitivity and specificity of >94%,34 and the CAM-ICU-7 (Table 5), a 7-item (0–7) scale derived from the CAM-ICU and the RASS scale.35

3-Minute Diagnostic Interview for CAM-defined Delirium (3D-CAM).

Reference: Palihnich et al.152

CAM-ICU-7.

| ITEMS | SCORE |

|---|---|

| Acute onset or fluctuating course Is the patient different than his/her baseline mental status? OR Has the patient had any fluctuation in mental status in the last 24 h as evidenced by fluctuation on a sedation/level of consciousness scale (such as RASS or GCS)? | Absent: 0 points: Present: 1 point |

| 2. Inattention Say to the patient: “I'm going to read you a series of 10 letters. Whenever you hear the letter “A”, indicate by squeezing my hand.” Read letters from the following list in a normal tone 3 seconds apart. S A V E A H A A R T (Errors are counted when patient fails to squeeze on the letter “A” or when the patient squeezes on any letter other than “A.”) | Absent (correct ≥ 8): 0 points: Inattention (correct 4−7): 1 point Severe inattention (correct 0−3): 2 points |

| 3. Altered Level of Consciousness Present if the actual Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale Score is anything other than alert and calm (zero) | Absent (RASS 0): 0 points: Altered level (RASS 1, −1): 1 point Severe altered level (RASS > 1, < −1): 2 points |

| 4. Disorganized thinking Yes/no questions 1. Will a stone float on water? 2. Are there fish in the sea? 3. Does one kilo weigh more than two kilos? 4. Can you use a hammer to pound a nail? Errors are counted when the patient answers a question incorrectly. Command: Say to patient ““Hold up this many fingers” (hold two fingers in front of patient). “Now do the same with the other hand” (Do not repeat number of fingers). An error is counted if patient is unable to complete entire command. | Absent (correct ≥ 4 0 points Disorganized thinking (correct 2, 3): 1 point Severe disorganized thinking (correct 0, 1): 2 points |

The final score of the CAM-ICU-7 ranges from 0 to 7, with 7 being the most severe. CAM-ICU-7 scores are further categorized into 0–2: no delirium, 3–5: mild to moderate delirium, and 6–7: severe delirium.

Reference: Khan et a al.154.

The CAM-ICU flowsheet is a simple algorithm that speeds up the diagnosis of delirium (Fig. 4). Studies have found excellent correlation (kappa 0.96) between the CAM-ICU flowsheet and the CAM-ICU for the diagnosis of delirium.36

CAM-ICU Flowsheet.

Reference: Miranda et al.153

The ICDSC37 checklist contains 8 items: altered level of consciousness, inattention, disorientation, hallucination-delusion-psychosis, psychomotor agitation or retardation, inappropriate speech or mood, sleep-wake cycle disturbance, and symptom fluctuation (Table 6). The presence of 4 or more of the above items indicates delirium/ The ICDSC is less popular than the CAM-ICU, except is some countries such as Japan, where it is more widely used than the CAM-ICU.26

ICDSC (Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist).

| FEATURES | NO | YES |

|---|---|---|

| Altered level of consciousness Deep sedation/coma: NOT EVALUABLE Exaggerated response: 1 point Normal wakefulness: 0 points Light sedation: 1 point (no recent sedatives)/ 0 points (recent sedatives) | 0 | 1 |

| Inattention Difficulty following simple commands or conversation | 0 | 1 |

| Disorientation The patient does not remember name, date, place, etc. | 0 | 1 |

| Hallucinations, delusion or psychosis Tries to pick up objects that are not there, or is afraid of the people around him. | 0 | 1 |

| Psychomotor agitation or retardation Hyperactivity: requires sedatives or restraint Hypoactivity: psychomotor retardation | 0 | 1 |

| Inappropriate mood or speech Inappropriate emotions, language, sexual interactions | 0 | 1 |

| Sleep-wake cycle disturbance Less than 4 h of sleep, sleeps all day, or wakes up frequently | 0 | 1 |

| Fluctuations Fluctuation of the above symptoms over a 24 h period | 0 | 1 |

| SCORE | CLASSIFICATION | |

| 0 points | Normal | |

| 1−3 points | Subclinical delirium | |

| 4−8 points | Delirium | |

Reference M Bergeron N et al.37

Two scales have been developed to assess the severity of delirium symptoms: the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 (DRS-R-98) and the Cognitive Test for Delirium (CTD). The DRS-R-98 (Table 7) is a 16-item scale (sleep-wake cycle disturbance, perceptual disturbances and hallucinations, delusions. lability of affect, language, thought process abnormalities, motor agitation, motor retardation, orientation, attention, short-term memory, long-term memory, visuospatial ability, temporal onset of symptoms, fluctuation of symptom severity, physical disorder). Thirteen of these items are indicative of severity and 3 are diagnostic. Each is scored from 0 to 3 to obtain a maximum of 46 points; the higher the score, the greater the severity of delirium. The scale has high sensitivity and specificity, and excellent inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation 0.97).38,39

Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 (DRS-R-98).

| Severity scale | Score |

|---|---|

| Sleep-wake cycle disturbance | 0. Not present 1. Mild sleep continuity disturbance at night or occasional drowsiness during the day 2. Moderate disorganization of sleep-wake cycle (e.g., falling asleep during conversations, napping during the day or several brief awakenings during the night with confusion/behavioural changes or very little night-time sleep) 3-Severe disruption of sleep-wake cycle (e.g., day-night reversal of sleep-wake cycle or severe circadian fragmentation with multiple periods of sleep and wakefulness or severe sleeplessness) |

| Perceptual disturbances and hallucinations | 0. Not present 1. Mild perceptual disturbances (e.g., feelings of derealization or depersonalization; or patient may not be able to discriminate dreams from reality) 2. Illusions present 3. Hallucinations present |

| Delusions. | 0. Not present 1. Mildly suspicious, hypervigilant, or preoccupied 2. Unusual or overvalued ideation that does not reach delusional proportions or could be plausible 3. Delusional |

| Lability of affect | 0. Not present 1. Affect somewhat altered or incongruent to situation; changes over the course of hours; emotions are mostly under self-control 2. Affect is often inappropriate to the situation and intermittently changes over the course of minutes; emotions are not consistently under self-control, though they respond to redirection by others 3. Severe and consistent disinhibition of emotions; affect changes rapidly, is inappropriate to context, and does not respond to redirection by others |

| Language | 0. Normal language 1. Mild impairment including word-finding difficulty or problems with naming or fluency 2. Moderate impairment including comprehension difficulties or deficits in meaningful communication (semantic content) 3. Severe impairment including nonsensical semantic content, word salad, muteness, or severely reduced comprehension |

| Thought process abnormalities | 0. Normal thought processes 1. Tangential or circumstantial 2. Associations loosely connected occasionally, but largely comprehensible 3. Associations loosely connected most of the time |

| Motor agitation | 0. No restlessness or agitation 1. Mild restlessness of gross motor movements or mild fidgetiness 2. Moderate motor agitation including dramatic movements of the extremities, pacing, fidgeting, removing intravenous lines, etc. 3. Severe motor agitation, such as combativeness or a need for restraints or seclusion |

| Motor retardation | 0. No slowness of voluntary movements 1. Mildly reduced frequency, spontaneity or speed of motor movements, to the degree that may interfere somewhat with the assessment 2. Moderately reduced frequency, spontaneity or speed of motor movements to the degree that it interferes with participation in activities or self-care 3. Severe motor retardation with few spontaneous movements |

| Orientation | 0. Oriented to person, place and time 1. Disoriented to time (e.g., by more than 2 days or wrong month or wrong year) or to place (e.g., name of building, city, state), but not both 2. Disoriented to time and place 3. Disoriented to person |

| Attention | 0. Alert and attentive. 1. Mildly distractible or mild difficulty sustaining attention, but able to refocus with cueing. On formal testing makes only minor errors and is not significantly slow in responses 2. Moderate inattention with difficulty focusing and sustaining attention. On formal testing, makes numerous errors and either requires prodding to focus or finish the task 3. Severe difficulty focusing and/or sustaining attention, with many incorrect or incomplete responses or inability to follow instructions. Distractible by other noises or events in the environment |

| Short-term memory | 0. Short-term memory intact. 1, Recalls 2/3 items; may be able to recall third item after category cueing 2. Recalls 1/3 items; may be able to recall other items after category cueing 3. Recalls 0/3 items |

| Long-term memory | 0. No significant long-term memory deficits 1. Recalls 2/3 items and/or has minor difficulty recalling details of other long-term information 2. Recalls 1/3 items and/or has moderate difficulty recalling other long-term information 3. Recalls 0/3 items and/or has severe difficulty recalling other long-term information |

| Visuospatial ability | 0. No impairment 1. Mild impairment such that overall design and most details or pieces are correct; and/or little difficulty navigating in his/her surroundings 2. Moderate impairment with distorted appreciation of overall design and/or several errors of details or pieces; and/or needing repeated redirection to keep from getting lost in a newer environment despite the presence of familiar objects 3. Severe impairment on formal testing; and/or repeated wandering or getting lost in environment |

| Optional diagnostic features | Score |

|---|---|

| Temporal onset of symptoms | 0. No significant change from usual or longstanding baseline behaviour 1. Gradual onset of symptoms, occurring over a period of several weeks to a month 2. Acute change in behaviour or personality occurring over days to a week 3. Abrupt change in behaviour occurring over a period of several hours to a day |

| Fluctuation of symptom severity | 0. No symptom fluctuation 1. Symptom intensity fluctuates in severity over hours 2. Symptom intensity fluctuates in severity over minutes |

| Physical disorder | 0. None present or active 1. Presence of any physical disorder that might affect mental state 2. Drug, infection, metabolic disorder, CNS lesion or other medical problem that specifically can be implicated in causing the altered behaviour or mental state |

Reference: Franco et al.155

The CTD scale assesses neurocognition without requiring a verbal response, and consists of 9 items grouped into 5 categories. The items contain descriptors, and each category is scored from 0 to 6 using a conversion table. Scores range from 0 to 30; the lower the score, the greater the severity of delirium. The diagnostic cut-off point for delirium is ≤18. The Delirium Motor Checklist (DMC) is used to assess the number of hyper- and hypoactive symptoms.33

A history of dementia is an important risk factor for developing delirium in the ICU. Identifying patients with previous cognitive impairment or at risk of developing such impairment could indicate which are more likely to develop delirium. The CDR scale (Table 8) is the gold standard for detecting the different stages of dementia: 0 - no dementia; 0.5 - questionable dementia, 1 - mild dementia, 2 - moderate dementia and 3 - severe dementia.39

Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale.

| None 0 | Questionable 0.5 | Mild 1 | Moderate 2 | Severe 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory | No memory loss or slight inconsistent forgetfulness | Mild consistent forgetfulness; partial re-collection of events; ‘benign’ forgetfulness | Moderate memory loss, more marked for recent events; defect interferes with everyday activities | Severe memory loss; only highly learned material retained; new material rapidly lost | Severe memory loss; only fragments remain |

| Orientation | Fully oriented | Fully oriented, but some difficulty with time relationships | Some difficulty with time relationships; oriented to place and person at examination but may have geographic disorientation | Severe difficulty with time relationships; Usually disoriented to time, often to place | Orientation to person only |

| Judgement and problem solving | Solves every day problems well and good control of business and finance; judgement good in relation to past performance | Mild impairment in solving problems, similarities, differences | Moderate difficulty in handling complex problems, similarities, differences; social judgement usually maintained | Severely impaired in handling problems, similarities, differences; social judgement usually impaired | Unable to make judgements or solve problems |

| Community affairs | Independent function at usual level in job, shopping, volunteer and social groups | Only doubtful or mild impairment, if any, in these activities | Unable to function independently at these activities though may still be engaged in some; may still appear normal to casual inspection | No pretence of independent function outside home Appears to be well enough to perform functions outside the home. | No pretence of independent function outside home Appears too ill to perform functions outside home |

| Home and hobbies | Life at home, hobbies, intellectual interests well maintained | Life at home, hobbies, intellectual interests well maintained or only slightly impaired | Mild but definite impairment of function at home; more difficult chores abandoned; more complicated hobbies and interests abandoned | Only simple chores preserved; very restricted interests, poorly sustained | No significant function at home |

| Personal care | Fully capable of self-care | Fully capable of self-care | Needs occasional prompting | Requires assistance in dressing, hygiene, keeping of personal effects | Requires much help with personal care; often incontinent |

Score only if impairment is due to cognitive loss, not limitations due to other factors. Dementia is considered severe when the CDR is 3.

Reference: Martin Sanchez et al.156

The AD8 test (Table 9) is derived from the CDR. Although it only consists of 8 yes/no questions, it has high sensitivity (97%) and a high negative predictive value (86%) for detecting mild, moderate or severe dementia (CDR greater than or equal to 1).39

AD8 test.

| ITEM | Remember: “"Yes, a change" indicates that you think there has been a change in the last several years cause by cognitive (thinking and memory) problems: | Yes, a change | No, no change | NA Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Problems with judgement (e.g. falls for scams, bad financial decisions, buys gifts inappropriate for recipients) | |||

| 2 | Decreased interest in activities and hobbies | |||

| 3 | Repeats questions, stories or statements | |||

| 4 | Trouble learning how to use a tool, appliance or gadget (e.g. VCR, computer, microwave, remote control, mobile phone) | |||

| 5 | Forgets correct month or year | |||

| 6 | Difficulty handling complicated financial affairs (e.g. balancing check book, income taxes, paying bills) | |||

| 7 | Difficulty remembering appointments | |||

| 8 | Consistent problems with thinking and/or memory |

AD8 TOTAL SCORE: One point is assigned for each “Yes, a change” response, so only the items in that column are counted toward the total score. >3-4 points indicates a high probability that the patient has cognitive impairment.

Reference: Carnero Pardo C, et al.157

Patients can be screened for delirium by trained nurses prior to undergoing a medical diagnosis. Nurse-administered scales include:

- -

The Delirium-O-meter (Table 10) - an observational delirium scale that requires minimal training. It consists of 12 observational behavioural items: sustained attention, shifting attention, orientation, consciousness, apathy, hypokinesia/psychomotor retardation, incoherence, fluctuations in functioning, restlessness, delusions, hallucinations, anxiety/fear. The total score ranges from 0 to 36, with 36 indicating the most severe delirium.40

Table 10.Delirium-O-meter.

0 1 2 3 Sustained attention Is able to concentrate for longer periods of time during activities/conversations. Absent-minded, questions need to be repeated sometimes Easily distracted, questions need to be repeated most of the time. Not able to maintain attention at all, reacts to all kinds of stimuli. Shifting attention Switches between conversation topics or activities without any problem. Occasionally continues talking about a previously discussed topic. Much difficulty shifting attention towards new activities/topics. Not at all able to raise attention or shift it towards new topics/activities. Orientation Says correct date, knows where he/she is and his/her way around, recognizes people No problems other than saying the correct date and day of the week. Disoriented to time and place, cannot find his/her own room, doesn't know where he/she is. Disoriented to time, place and person, recognises family members insufficiently Consciousness Appears wide awake and alert during the day. Distracted look, as if he/she has just woken up and is not fully awake. Clearly appears sleepy, eyes frequently closed, but does respond Hard to awaken, hardly responds when spoken to Apathy Starts conversation, shows interest, appears to be motivated to do something Shows interest only when others invite him/her, but does not appear “empty" Almost no initiative and shows little interest in others (appears “empty”) Does not do anything, appears to be emotionally "empty" Hypokinesia/psychomotor retardation Normal spontaneous pattern of movements. Often sits inactively but just a little encouragement leads to activity Little spontaneous movement, arms motionless or crossed No movement of arms or legs unless stimulated strongly Incoherence What the patient says is easy to understand even for someone who doesn't know him/her very well. What the patient says is not always easy to understand, sometimes jumps from one topic to another. Clearly difficult to follow, associative, sentences seem unrelated, sometimes stops in the middle Not able to express a coherent thought, unfinished sentences, loose words, yells, moans. Fluctuations in functioning No diurnal variation in functioning, normal sleep-wake cycle. Minimal fluctuations (during the day or during the sleep-wake cycle) Moderate fluctuations (during the day or during the sleep-wake cycle) Very marked diurnal variations or severely altered sleep-wake cycle. Restlessness Is able to sit down and relax, work on something or talk to someone without getting restless. A little bit jumpy, fidgety, restless, rocks chair. Agitated, paces up and down the room, slightly irritated, restless arm movements. Extremely restless, irritable, plucking, oppositional behaviour, pulls out catheter, restrictive measures used. Delusions Thoughts are "in sync" with reality, there are no unfounded or unrealistic beliefs, patient is not suspicious or distrustful. Somewhat suspicious, distrustful, sometimes feels like he left behind, often asks “why is this…” Clearly suspicious, has unrealistic, unfounded or strange ideas, for example, says he lives in the hospital Extremely suspicious or convinced of strange ideas, making it very difficult to redirect his or her thoughts Hallucinations Perception; what patient sees/hears/smells/touches/feels matches reality Occasional distorted perception of objects, e.g. curtains/wallpaper motifs seen as little animals Perceives people, objects, smells, tastes, sounds or animals that are not really there, but can be redirected. Constantly perceives things that are not there, cannot be redirected, interaction is difficult. Anxiety/fear Feels at ease, not anxious Somewhat apprehensive about what is going on or what will happen. Clearly anxious, fearful, needs some reassurance Extremely anxious, frightened, needs a lot of reassurance Reference: de Jonghe et al.158

- -

The Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (Nu-DESC) (Table 11) - a delirium screening tool for nurses that assesses 5 features: disorientation, inappropriate behaviour, inappropriate communication, illusions/hallucinations, and psychomotor delay. Each item is scored from 0 to 2, with 0 indicating no symptoms and 2 severe symptoms. A score greater than or equal to 2 indicates a positive screening for delirium29,41

Table 11.The Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (Nu-DESC).

Symptom 00: 00am/8: 00am 8: 00am/4: 00 pm 4: 00 pm/00: 00am 1. Disorientation Verbal or behavioural manifestation of not being oriented to time or place or misperceiving persons in the environment 2. Inappropriate behaviour Behaviour inappropriate to place and/or for the person 3. Inappropriate communication Communication inappropriate to place and/or for the person 4. Illusions/hallucinations Seeing or hearing things that are not there; distortions of visual objects 5. Psychomotor retardation Delayed responsiveness, few or no spontaneous actions/words Reference: Gaudreau et al.159

Each feature is rated from 0 to 2 for severity, where 0 = absent, 1 = mild, and 2 = severe. Positive Nu-DESC is a score ≥2, the maximum total score is 10.

- -

The 4A test (4AT) can be administered in less than 2 min by healthcare professionals without special training in screening for delirium. It consists of 4 items: the first measures the patient's level of alertness as observed by the operator (score 0 or 4); items 2 and 3 measure orientation and attention using the Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT) and Backward Months Test. Each item is scored from 0 to 2; and item 4 assesses acute change or fluctuating course (score 0–4). A score of 0 indicates unlikely delirium; a score of 1−3 indicates possible cognitive impairment, and a score ≥4 suggests delirium.40 (Table 12)

Table 12.4AT Test.

ALERTNESS This includes patients who may be markedly drowsy (e.g., difficult to rouse and/or obviously sleepy during assessment) or agitated/hyperactive. Observe the patient. If asleep, attempt to wake with speech or gentle touch on shoulder. Ask the patient to state his or her name and address to proceed with scoring. Normal (patient is fully alert (but not agitated) throughout assessment): 0 points Briefly sleepy for <10 seconds after waking, then normal: 0 points Clearly abnormally drowsy: 4 points AMT4 Age, date of birth, place (name of the hospital or building), current year. No mistakes: 0 points 1 mistake: 1 point 2 or more mistakes/untestable: 2 points Attention Ask the patient: "Please tell me the months of the year backwards, starting at December”. To assist initial understanding one prompt of "what is the month before December?" is permitted. Recites 7 months or more correctly: 0 points Starts but scores <7 months, or refuses to start: 1 point Untestable (cannot start because unwell, drowsy, inattentive): 2 points ACUTE CHANGE OR FLUCTUATING COURSE Evidence of significant change or fluctuation in: alertness, cognition, other mental function (e.g., paranoia, hallucinations) arising over the last 2 weeks and still evident in last 24 h. No: 0 points Yes: 4 points 4 or more points: possible delirium +/− cognitive impairment.

1−3 points: possible cognitive impairment.

0 points: Delirium or severe cognitive impairment unlikely but possible if information is incomplete.

Reference: Saller et al.160

According to the neuroinflammatory hypothesis of delirium, proinflammatory factors such as procalcitonin, IL-8, IL-6, and S100 beta play an important role in the development of the syndrome. These factors could cause neuronal apoptosis and synaptic dysfunction, promoting the development of delirium. New lines of research are attempting to determine how these proinflammatory molecules can be used as a diagnostic tool. The platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) is calculated on admission to the ICU by dividing the platelet count by the lymphocyte count. It is a simple, inexpensive procedure that could be used to predict delirium in critically ill patients. A high PLR (>100) on admission to the ICU has been associated with a higher incidence of delirium. PRL, however, is not a validated diagnostic method.15

Specific EEG patterns associated with postoperative delirium have been described.42 Comatose ICU patients who spend more time in burst suppression are more likely to develop delirium after recovery from coma.43

Further studies are needed to validate these approaches to diagnosing delirium.

Prevention of deliriumClinicians need to consider both widely applicable non-pharmacological and pharmacological strategies when treating delirium.

General approach and non-pharmacological strategies| Recommendations 1. Anticipate delirium (1). We recommend screening for baseline risk factors: previously diagnosed or undiagnosed brain disease (dementia, stroke, Parkinson's), advanced age, institutionalized patient (nursing home), chronic illness (diabetes mellitus, dependency, hypertension, HIV, etc.), visual and/or hearing deficits.98–107Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 2. Anticipate delirium (2). We recommend screening for precipitating risk factors: drugs, infection, dehydration, immobility or physical impairment, malnutrition, catheters, electrolyte disturbance, sleep deprivation.102–108,113Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 3. Anticipate delirium (3). We recommend administering predictive scales (DELIPRECAS, PRE-DELIRIC) to evaluate the likelihood of developing delirium 93,94,110–112Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 4. We suggest performing early tracheostomy. This reduces the need for sedation and improves the patient's ability to communicate5,116–119Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Conditional recommendation for the intervention. |

| 5. We recommend administering non-opioid analgesics such as paracetamol, dipyrone, ketorolac and dexketoprofen to reduce opioid requirements.5,104–106,108–111Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 6. We recommend early prevention and treatment of withdrawal syndrome related to substances consumed before admission to the SCCU (alcohol, nicotine, benzodiazepines, opiates) or during admission (gradual dose tapering after prolonged sedation-analgesia).5,109,111,129–131Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 7. Cognitive function. We recommend taking measures to stimulate the patient’s orientation and awareness of their surroundings, such as implementing long, flexible visiting hours, placing a clock within sight, and providing natural lighting (night and day). All staff that come into contact with the patient must wear a name badge, introduce themselves when addressing the patient, and talk as much as possible to them. Explain the patient’s illness to them and all the procedures and interventions they undergo. Organise therapeutic activities: discussion and conversation on current or interesting topics, structured recall, etc. Allow the patient to wear their dentures, if possible, to read newspapers and books, listen to music, the radio and television. Orientation: minimise the number of changes of room or cubicle.5,98–102,107,108Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 8. Sleep deprivation. We recommend avoiding pharmacological sedation and taking measures to promote sleep hygiene: darkness and silence at night, relaxing music, night-time drinks (a glass of milk or non-stimulating infusion), and programming medication rounds and vital assessments to respect sleep.5,98–102,107,108Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 9. Immobility. We recommend early mobilization, passive and active exercise sessions, and limiting bed rest time.5,98–102,107,108,110,113Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 10. Impaired eyesight and hearing. We recommend promoting the use of glasses and hearing aids, eye and ear hygiene, and adapting the surroundings to patients with impaired eyesight and hearing.5,98–102Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 11. Nutrition and hydration. We suggest making sure that patient drink fluids and accompanying them during meals to monitor their food and fluid intake.5,98–103Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 12. Voiding. We recommend avoiding urinary catheters as far as possible, and monitoring for signs of urinary retention, constipation and faecal impaction. Monitor the patient’s bowel movements and urine output.98–103Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 13. We suggest that patients are not left alone. Someone should be present in the room at all times to avoid self-harm or accidents.94,108,110,114,115Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Conditional |

| 14. We recommend introducing flexible visiting hours for relatives, although it is advisable to avoid overcrowding in the patient’s room and to limit the duration of visits. A caregiver must be in the room at all times.5,94,110,114,115Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 15. Physical restraints. We recommend avoiding mechanical restraints as they cause fear and agitation. They should only be used in exceptional circumstances and should be removed as soon as symptomatic treatment is effective.5,99–102,107,108,110,113Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 16. Comfortable surroundings. We suggest avoiding noisy surroundings, excessive movement around the patient, frequent staff and room changes, and moving the objects in the patient’s room.5,109–111,114Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Conditional |

As delirium is a potentially preventable syndrome, implementing protocols in high-risk patients will improve quality of care, and reduce both the length of SCCU stay and in-hospital mortality. This is one of the objectives of the ZDP. In a recent meta-analysis evaluating randomized clinical trials analysing pharmacological or nonpharmacological treatment for the prevention of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients that included a total of 16,087 patients, the authors found no clear evidence of benefit for pharmacological therapy (cholesterase inhibitors, antipsychotics or melatonin).44 However, this and other recent studies in a broad range of patients and settings (acute hospitalization and perioperative care) have shown that interventions on different risk factors are effective in reducing the incidence of delirium.45–47 Specifically, a meta-analysis of 7 studies found that non-pharmacological interventions significantly reduced the incidence of delirium compared with usual care, with a relative risk (RR) of 0.73 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.63 to 0.85.46 Therefore, risk factor management, not pharmacological treatment, is the fundamental pillar for preventing delirium and its incidence in elderly hospitalized patients.

One of the first interventional programs developed to reduce the incidence of delirium was published 18 years ago, and showed that addressing 6 risk factors (cognitive impairment, sleep deprivation, immobility, visual impairment, hearing impairment, and dehydration) reduced the incidence of delirium by 40%–15.0% in the non-intervention group and 9.9% in the intervention group (OR 0.60 [0.39 to 0.92]).48 These results have been reproduced in other studies, and confirm that interventional programs can reduce the incidence of delirium by 40% in elderly patients without a terminal illness who are hospitalized or admitted to a nursing home.49 These prevention programs are cost-effective50 and require a multidisciplinary group of professionals with specific training backed by the healthcare system.51 General measures start with prompt, appropriate treatment of the underlying medical disease. Elderly patients can now benefit from a number of programs based on protocols that can be applied by family members and trained volunteers to address different features, such as orientation and mobility, sensory impairment, sleep and eating.52 The main role of healthcare personnel in these protocols is to maximise hydration, avoid unnecessary catheterization, ensure the patients receive natural lighting during the day and avoid artificial light at night, provide patients with glasses and hearing aids if they required these prior to hospitalisation, encouraging family support, orientation, entertainment, communication, facilitating sleep using earplugs and eye masks, and avoiding sensory deprivation. Other measures include early mobilization, physical and occupational therapy, removing physical restraints and promoting room sharing.53,54

A comprehensive delirium prevention strategy must also take into consideration patients that are scheduled for surgery and subsequent admission to an SCCU.55 The ABCDEF bundle has been developed for these cases56:

- •

Assess, prevent, and manage pain. Critically ill patients experience pain at rest and during routine procedures. This can cause delirium if inadequately treated.2,56,57

- •

Both spontaneous awakening (SAT) and spontaneous breathing (SBT) trials. SAT involves temporary withdrawal of sedation; SBT involves periods of minimal respiratory assistance.56,57

- •

Choice of analgesia and sedation. Several validated scales for assessing the level of sedation ICU are available, for example, the Richmond Sedation-Agitation Scale (RASS) or the Riker Sedation-Agitation Scale.52,56,57

- •

Delirium - assess, prevent, and manage. A key component of delirium management is early identification and modification of risk factors.56,57 Two very useful tools for identifying the individual risk of delirium are the PRE-DELIRIC and the DELIPRECAS models. The PRE-DELIRIC model is a validated scale that evaluates 10 risk factors to predict the risk of delirium in critically ill patients: age, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score, neurological involvement, type of patient (surgical, medical, or trauma), infection, metabolic acidosis, use of sedatives and morphine, kidney failure, and urgent admission. This model identifies high-risk patients so that clinicians can promptly initiate targeted preventive measures.58,59 The model is shown in Table 13. The DELIPRECAS (DELIrium PREvention CArdiac Surgery) model consists of 4 well-defined clinical risk factors: age over 65 years, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 25–26 points (possible impairment of cognitive function) or <25 (impairment of cognitive function), insomnia needing medical treatment, and low physical activity (walk less than 30 min a day). When administered in the preoperative period, this tool can predict the risk of developing postoperative delirium in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.60 The model is shown in Table 14. An online risk calculator is also available: www.biocritic.es/deliprecas.

Table 13.PRE-DELERIC scale.

The risk of delirium is calculated using the formula risk of delirium = 1/(1 + exp− [−6.31]) +0.04 × age +0.06 × APACHE II 0 for no coma +0.55 for drug-induced coma +2.70 for miscellaneous coma +2.82 for combination coma 0 surgical patients +0.31 for medical patients +1.13 for trauma patients +1.38 for neurology/neurosurgical patients +1.05 for Infection +0.29 for metabolic acidosis 0 for no morphine use +0.41 for 0.01 to 0.71 mg/24 h morphine use +0.13 for 0.72 to 18.6 mg/24 h morphine use +0.51 for >18.6/24 h morphine use +1.39 for use of sedatives +0.03×urea concentration (mmol/L) +0.40 urgent admission Reference: Adapted from van den Boogaard et al.58

Table 14.DELIPRECAS Scale (DELIrium PREvention CAdiac Surgery).

The risk of delirium is calculated using the formula risk of delirium = 1/(1 + exp- (−4.092 + 1.648 for cognitive impairment + 2.294 for possible cognitive impairment + 1.108 for over 65 years + 1.010 for low physical activity + 1.107 for insomnia requiring medical treatment) Automatic calculator in www.biocritic.es/deliprecas

The intercept is −4.092; the other numbers represent the reduced regression coefficients (weights) of each risk factor.

Adapted from de la Varga-Martínez O et al.60

- •

Early mobilisation and exercise.56 Early mobilisation consists of a variety of activities ranging from passive range of motion to assisted ambulation. It is both safe and practical in critically ill patients and reduces the duration of delirium, time on mechanical ventilation, length of ICU stay, and total length of hospital stay.61

- •

Family engagement and empowerment.56 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that a series of protocolized family support interventions reduced ICU length of stay without affecting mortality.62 Another approach that has shown promising results is to introduce flexible visiting hours for family members.63

These measures are summarized in Table 15.

General strategies to prevent and treat delirium in the SCCU.

| Avoid | Promote |

|---|---|

| Artificial light at night | Natural daylight |

| Noise | Respect sleep |

| Immobility | Early mobilization |

| Unjustified sedation | Light sedation |

| Dehydration | Use of glasses and/or hearing aids during the day |

| Pain | Use of earplugs and eye masks at night |

| Restricted family visits | Family engagement |

| Physical restraints | Communication |

| Unnecessary procedures (e.g. catheterizations) | Appropriate ambient temperature |

| Clocks, calendars, radio, music and/or TV | |

| Physical and occupational therapy | |

| Room sharing |

One of the strategies used to prevent delirium in SCCUs is early tracheotomy in patients on prolonged mechanical ventilation.56 This has been associated with a decrease in the duration of mechanical ventilation, reduced sedation requirements, better patient communication, and shorter SCCU stay.64–66 In their 2021 retrospective study, Gazda AJ et al. found that early tracheostomy was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of delirium in all subgroups of medical and nonsurgical patients.67

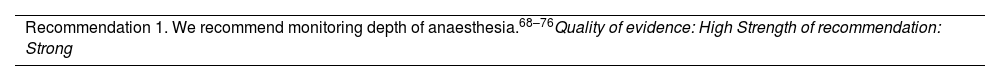

Importance of neuromonitoring during anaesthesia and in the ICU| Recommendation 1. We recommend monitoring depth of anaesthesia.68–76Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

There is a widespread belief that the effects of general anaesthesia are temporary; however, recent studies suggest that it may have long-term effects on memory and perception. Several authors have found evidence of an increased risk of post-anaesthesia cognitive disorders and memory impairment in elderly patients.68

The main hypothesis is that excessively deep anaesthesia (together with surgical and patient risk factors) may increase the risk of postoperative delirium. For this reason, recent research has focussed on the association between monitoring the depth of anaesthesia (using processed EEG) and postoperative delirium. Pivotal studies on the incidence of delirium and its association with depth of anaesthesia have been published by Radtke69 in Germany, Chan70 In Hong Kong (the CODA [Cognitive Dysfunction after Anesthesia] study, Wildes71 in the US, who led the important ENGAGES (Electroencephalography Guidance of Anaesthesia to Alleviate Geriatric Syndromes) study, and Evered72 in 2021. Three important meta-analyses (Miao,73 Jansen74 and Shan75) have also reported interesting results. While Evered, Chan, and Radtke showed that BIS-guided depth of anaesthesia monitoring led to a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of delirium, the meta-analyses published by Miao and Jannsen found no statistically significant association. Wildes et al., in their study of 1213 patients, reported a 3% higher incidence of delirium in the neuromonitoring group.

A single-centre, prospective, double-blind, observational study conducted at the Miguel Servet University Hospital and published in 2022 divided patients aged over 65 years of age undergoing surgery under general anaesthesia into 2 groups: with and without BIS neuromonitoring. Investigators observed a higher incidence of postoperative delirium and a longer hospital stay in the no BIS group vs less time in deep anaesthesia planes (BIS < 40), shorter hospital stay, and a lower incidence of mortality in the BIS monitoring group.76

This suggests that neuromonitoring to prevent episodes of deep anaesthesia while under general anaesthesia may reduce the incidence of postoperative delirium; however, further studies are needed to clarify this benefit.

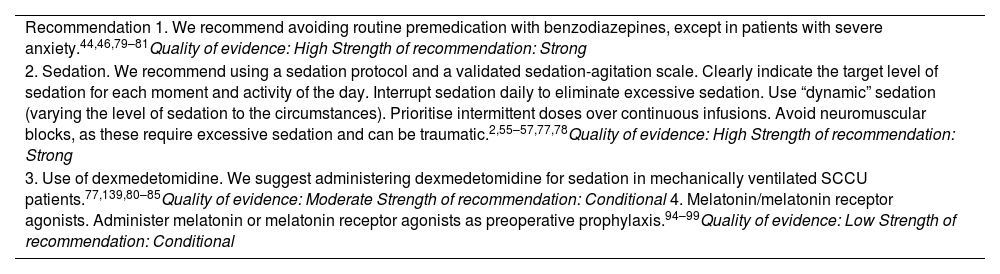

Pharmacological prevention of delirium| Recommendation 1. We recommend avoiding routine premedication with benzodiazepines, except in patients with severe anxiety.44,46,79–81Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 2. Sedation. We recommend using a sedation protocol and a validated sedation-agitation scale. Clearly indicate the target level of sedation for each moment and activity of the day. Interrupt sedation daily to eliminate excessive sedation. Use “dynamic” sedation (varying the level of sedation to the circumstances). Prioritise intermittent doses over continuous infusions. Avoid neuromuscular blocks, as these require excessive sedation and can be traumatic.2,55–57,77,78Quality of evidence: High Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 3. Use of dexmedetomidine. We suggest administering dexmedetomidine for sedation in mechanically ventilated SCCU patients.77,139,80–85Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Conditional 4. Melatonin/melatonin receptor agonists. Administer melatonin or melatonin receptor agonists as preoperative prophylaxis.94–99Quality of evidence: Low Strength of recommendation: Conditional |

Several classes of drugs may increase the likelihood of delirium, and this should be taken into consideration when prescribing high-risk drugs.

The first delirium prevention strategy is to avoid the use of unjustified, particularly deep, sedation. All SCCU patients receiving sedation should be monitored, and “dynamic sedation” and “sequential sedation” protocols should be used whenever possible.77,78 Benzodiazepines should also be avoided, provided the patient does not present alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome.79

Dexmedetomidine, an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, is indicated for light, cooperative sedation. Dexmedetomidine in ventilated patients reduces the risk of delirium and the duration of mechanical ventilation compared with both lorazepam80 and midazolam,81 although it increases the risk of bradycardia, and only dexmedetomidine compared with placebo is likely to reduce the incidence of delirium.82 The results of a randomized clinical trial in 30 critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation (20 treated with dexmedetomidine and 10 with placebo) showed that total sleep time and sleep efficiency were higher in the group receiving dexmedetomidine.83 A randomized controlled trial published in 2021 comparing dexmedetomidine and propofol in mechanically ventilated patients with sepsis found no significant differences in the incidence of delirium.84 Another randomized controlled trial (currently ongoing) is comparing the incidence of delirium in elderly cardiac surgery patients with or without a single postoperative dose of dexmedetomidine to induce sleep.85

Haloperidol, a first-generation antipsychotic neuroleptic, has been assessed as a delirium prophylaxis. One study showed that the drug reduced the incidence and severity of delirium in patients over 65 years of age undergoing non-cardiac surgery.86 Despite this finding, there is insufficient evidence to recommend haloperidol for pharmacological prophylaxis against delirium. Atypical antipsychotics have also been evaluated in this regard, although there is no evidence that they prevent delirium.87

Some authors have recently suggested that statins may protect against delirium in patients in SCCUs. According to this hypothesis, these 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl–coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors protect against delirium by mitigating 2 inflammatory responses: central nervous system inflammation (thereby preserving the blood-brain barrier) and systemic inflammation, both of which are involved in the pathogenesis of delirium.88–90 However, a sub-study of a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing rosuvastatin and placebo in acute respiratory distress syndrome found no effect on the incidence of delirium or on overall long-term cognitive decline.91

Another drug that has recently come under consideration for the prevention of delirium is ketamine, an intravenous N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist with anaesthetic, analgesic, antidepressant and anti-inflammatory properties. Intraoperative administration of ketamine significantly reduces postoperative interleukin-6 concentrations.92 However, a randomized controlled trial comparing a single intraoperative subanaesthetic dose of ketamine vs placebo found no difference in the incidence of postoperative delirium. The incidence of hallucinations and nightmares, however, was higher in the ketamine groups.93

There is growing interest in the use of melatonin for the prevention of delirium in hospitalized patients. Melatonin, a natural hormone produced by the pituitary gland, is responsible for regulating the sleep-wake cycle. Its use has been studied for insomnia, jet lag, circadian rhythm disturbances in the blind, shift work changes, and, more recently, for the prevention of delirium.94,95 Recent studies suggest that preoperative melatonin levels in cerebrospinal fluid may correlate with the risk of developing delirium after hip fracture surgery.96 The effect of ramelteon, a selective MT1/MT2 receptor agonist, on the incidence of delirium in both hospitalized and SCCU patients has also been explored. Although the optimal doses remain unclear, there is increasing evidence of the beneficial effect of both melatonin and melatonin receptor agonists, and they have been recommended as a preoperative prophylaxis for delirium,97 but more studies are needed before this recommendation can be generalized.98 A recent meta-analysis of 58 randomized clinical trials published in 2019 defends the combination of ramelteon with haloperidol and lorazepam in both the prevention and treatment of delirium.99

Another molecule involved in regulating the sleep-wake cycle is the neuropeptide orexin, which binds to OX1 and OX2 receptors to promote wakefulness. Several studies have shown that the dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORA) suvorexant and lemborexant are useful in sleep disorders.100,101 The recent novel, promising results obtained with these drugs suggest that they may prevent delirium, although this will have to be confirmed in futures randomised clinical trials.102,103

In conclusion, no pharmacological agent has so far shown effectiveness in preventing delirium, and given the heterogeneous nature of the disorder, optimal treatment will likely depend on each patient’s risk factors, neurological and systemic comorbidities, and metabolic and physiological profile.

Treatment of deliriumThe acute, potentially life-threatening causes of delirium must be taken into account when treating this disorder. These include hypoxaemia, hypotension, hypoglycaemia, electrolyte disturbances, and drug intoxication or withdrawal, in addition to pain, medication, etc. Prevailing circumstances, such as the patient’s surroundings (reducing noise) and sleep hygiene, must also be optimized. Up to 50% of delirium episodes in patients admitted to palliative care units can be reversed, particularly when delirium has been triggered by medications, infections or electrolyte disturbances.104,105 Drugs are one of the most common causes of delirium.106

The standard therapeutic approach to delirium includes cognitive training programs, reorientation measures, administration of neuroleptics, and adequate pain treatment.107,108 The first step in treating delirium should be to investigate the underlying medical triggers and optimise non-pharmacological interventions.109–111 In patients that are severely distressed by their symptoms, pose a safety risk to themselves or others, or impede essential care procedures, it is acceptable to treat the symptoms of delirium with drugs.112

Non-pharmacological treatment| Recommendation 1. We recommend effective communication and orientation (telling the patient where they are, who the healthcare professional is and what they do, placing clocks and calendars in plain sight, and reducing sensory deprivation by making it easier for patients to use glasses and hearing aids). Promote sleep, and avoid disrupting the patient’s sleep-wake cycle by adjusting lighting and noise110,111,116,134,141Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 2. We recommend encouraging family engagement118,115,111,116,117Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Strong |

| 3. We recommend avoiding or reducing as far as possible the use of urinary catheters, vascular catheters, and physical restraints, preventing malnutrition and constipation, and promoting early mobilization.111,117,141,134,120Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Strong |

The first pillar in the treatment of delirium currently consists of implementing and emphasizing the importance of the general, non-pharmacological approach to preventing delirium: improving sleep, providing family support, re-orientation, verbal consolation or comforting, etc. This, however, can be difficult to implement in SCCU patients, particular if they are sedated.113

Hyperactive delirium, which presents with psychomotor agitation, is often managed with physical restraints and ligatures. This is a highly controversial approach that has medico-legal connotations and should be avoided as far as possible. Physical restraints, which staff often use to reduce the risk of self-harm, can actually increase the risk of injury, and should therefore be minimized. In SCCUs, physical restraints may be needed to prevent the removal of endotracheal tubes, intra-arterial devices, and central venous catheters. Their use, if unavoidable, should be carefully monitored to avoid the risk of injury, and they should be removed as soon as they are no longer indicated.111

Bowel and bladder emptying should be monitored, urinary catheters should be avoided as far as possible, malnutrition and constipation should be prevented, and early ambulation should be encouraged.111

Nonpharmacological strategies also include effective communication and reorientation (e.g. telling the patient where they are, who the healthcare professional is and what they do, placing clocks and calendars in sight, and reducing sensory deprivation by making allowing patients to use glasses and hearing aids),114 and controlling the room lighting to ensure that it is bright during the day and dark and quiet at night.

Patients with delirium should be reassured; family, friends and caregivers should be brought in to help with this, and an appropriate care environment should be created.115–117 There is evidence that involving family members in the patient’s care is a fairly simple strategy that can shorten the hospital stay and reduce the family’s anxiety.111,118 One recent study provides preliminary support for the use of pre-recorded family video messages to reduce agitation in certain delirious hospitalised patients, although further studies are needed to determine the benefit of this strategy within a multi-component intervention.119,120

Introducing individualized physical exercise programs in hospitalized geriatric patients, particularly those with hypoactive delirium, during periods when they are able to cooperate would have both functional and cognitive benefits.121

Pharmacological treatmentHyperactive delirium| Recommendation 1. We recommend administering low-dose haloperidol or atypical neuroleptics. Nevertheless, comorbidities should be assessed on a case-by-case basis, and the immediate reduction of symptoms should be weighed up against the risks of antipsychotic-induced sedation and complications115,127–137Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Strong 2. We recommend avoiding benzodiazepines in elderly patients and in those with lung disease.132,115,122,140Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Strong 3. We recommend benzodiazepines or clomethiazole as the treatment of choice in patients with alcohol withdrawal63,107,115,140,134Quality of evidence: Moderate Strength of recommendation: Strong 4. We suggest considering the use of melatonin in patients with insomnia and/or poor response to other treatments141,142Quality of evidence: Low Strength of recommendation: Conditional |

Most reviews focus on hyperactive delirium, which usually requires a more proactive approach due to the potential safety risk for the patient and their surroundings. It is essential to know the patient's history and background medication and plan the pharmacological treatment accordingly, as this will reduce potential side effects.

A number of drugs are suitable for symptom-oriented management. Their use will depend on the clinical picture.

- •

Sedative-hypnotics

Sedatives are widely used to manage anxiety and agitation in critically ill patients. Although they are fully justified, several factors must be taken into consideration:

- •

Excessive or unjustified use of these drugs produces oversedation and increases morbidity (delirium, time on mechanical ventilation, acquired weakness, avoidable tracheostomies, etc.), care costs, and mortality.

- •

The type of sedative used may increase the incidence of delirium and withdrawal. There is scientific evidence that benzodiazepines are associated with delirium and cognitive dysfunction.80,122

- •

Hyperactive delirium manifests with psychomotor agitation. Treating agitation with sedatives alone will mask the symptoms and complicate management in the short, medium, and long term.

After the publication of recommendations to avoid benzodiazepines in the management of hyperactive delirium, practically the only remaining alternatives for controlling agitation in these patients were propofol and neuroleptics. Clonidine is available as an adjuvant in some ICUs, but its use is far from widespread or universally accepted.

Dexmedetomidine, an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist that acts in the locus coeruleus of the brain stem to produce sedation, is now gaining ground in the management of agitation and hyperactive delirium in critically ill patients.

A recent study showed that dexmedetomidine was superior to haloperidol in intubated, mechanically ventilated patients with hyperactive delirium, and reduced ICU stay by 5 days.123 The same study showed that continuous infusion shortened the duration of mechanical ventilation and time to extubation, reduced the need for other sedatives, opiates and antipsychotics, and led to earlier resolution of delirium compared to placebo.123 According to some studies, dexmedetomidine increases the incidence of bradycardia but decreases the incidence of mortality,124 while in others it has proven useful as a rescue drug for the treatment of delirium-induced agitation in non-intubated patients that do not respond to haloperidol, and appears to be more effective, safe, and less expensive than haloperidol.125 Similarly, some studies have shown that dexmedetomidine is effective in treating delirium associated with cancer pain, post-surgical pain, and alcohol withdrawal.115

- •

Neuroleptics

It is commonly accepted that antipsychotics, if required, should be administered at the lowest dose for the shortest time possible, giving preference to antipsychotics with few anticholinergic effects such as haloperidol. Haloperidol is still recommended as the first-line antipsychotic and is therefore widely used to treat hyperactive delirium,126 although the recommendation is based on weak evidence. Several studies have concluded that using antipsychotic agents to treat delirium does not reduce the duration or severity of the episode, the length of stay in the ICU or on the ward, or the incidence of mortality116,127–137; therefore, the decision whether to use such agents must consider the trade-off between an immediate reduction of agitation, hallucinations, and delusions versus the risks of sedation and antipsychotic-induced complications.111

Low doses of haloperidol or atypical neuroleptics are recommended in patients with productive psychotic symptoms, regardless of whether the delirium is hyperactive or hypoactive.111 High-dose haloperidol is associated with an increased likelihood of delirium the following day.110 Furthermore, intravenous haloperidol administration needs to be titrated under cardiac monitoring, since the use of haloperidol can cause QT interval prolongation as well as torsade de pointes tachycardia.

Atypical neuroleptics (risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine) are valid alternatives to haloperidol. Their efficacy is comparable, they are faster-acting, and produce fewer extrapyramidal symptoms.113,115,138 Blood count and liver parameters must be closely monitored in patients taking these drugs.

Specifically, quetiapine has shown earlier resolution of delirium compared to placebo in patients treated with haloperidol.88,107 Although it is gaining ground on haloperidol, it has not yet displaced it as first-line treatment because, among other reasons, it cannot be administered parenterally.

- •

Analgesic treatment

Many critically ill patients experience pain, not only due to the pathology that led to SCCU admission, but also to the procedures they undergo, such as tracheal intubation, surgical interventions, and mechanical ventilation. Pain is a predisposing factor for delirium; therefore, adequate pain management is crucial for the prevention and treatment of delirium. This includes:

- •

Correct assessment of pain using verbal or analogue scales in cooperative patients and behavioural scales in uncooperative patients.

- •

The use of non-pharmacological measures, such as early mobilization, position changes, massages, relaxation techniques, mindfulness, etc.

The potency of the analgesic drug used must be proportional to the level of pain, and it is important to develop and follow postoperative pain and sedation protocols based on multimodal, systemic and regional analgesia in order to minimize the use of opioids.

- •

Benzodiazepines

Long-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam) are not indicated for agitation and can promote delirium. They can also cause confusion and drowsiness, particularly in the elderly.115

These drugs should be reserved for specific indications,14 such as delirium related to alcohol or withdrawal from sedatives or other substances, in which cases prophylactic use may also be indicated.107,111,115,134

- •

Other drugs

Several studies have documented the efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of postoperative delirium that does not respond to conventional treatment with antipsychotics or benzodiazepines, and in patients with insomnia.141,142

Some studies have also investigated the use of thiamine as an adjuvant in the prevention and treatment of delirium in critically ill patients. Because of its low cost, availability, and minimal side effects, thiamine supplementation is a promising strategy, but further studies are required.143

Cholinesterase inhibitors such as rivastigmine, donepezil and galantamine have occasionally been used, but evidence regarding their efficacy is inconclusive.164

In patients with epilepsy, antiepileptic drugs may be an option.144

Some studies support the effectiveness of low-dose trazodone in contrasting aggressiveness and behavioural disorders in patients with depression, insomnia, and dementia suffering from agitation.144

Table 16 lists the doses, precautions, and observations regarding the aforementioned drugs.

Pharmacological treatment of delirium.

| Drug | Dose | Observations | Precautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haloperidol | 0.5−5 mg/8–12 h | Oral, IM, IV Standard first-line antipsychotic | Caution in heart failure, arrhythmia, kidney or liver failure, electrolyte disturbances, Parkinson’s. May cause QT interval prolongation and NMS. |

| Dexmedetomidine | 0.2−0.7 mcg/kg/min | IV Haloperidol-resistant delirium related to cancer pain or alcohol withdrawal. | Bradycardia and hypotension. |

| Risperidone | 0.25−1 mg/12 h | Oral, IM Atypical antipsychotic. Not available in iv presentation. | Caution in liver and kidney failure (dose adjustment), dementia, heart failure. May cause NMS and tardive dyskinesia (less frequently than haloperidol). |