Due to its association with systemic diseases and treatment, uveitis requires a multidisciplinary approach; however, there are few studies in uveitis units in Latin America.

ObjectiveTo describe the clinical and therapeutic features of patients treated in the Uveitis Unit of the Hospital de Clínicas Dr. Manuel Quintela in Montevideo, Uruguay.

Materiales y métodosObservational, descriptive, cross-sectional study in patients aged ≥15 years, attended from October 2018 to January 2020 with an uveitis diagnosis.

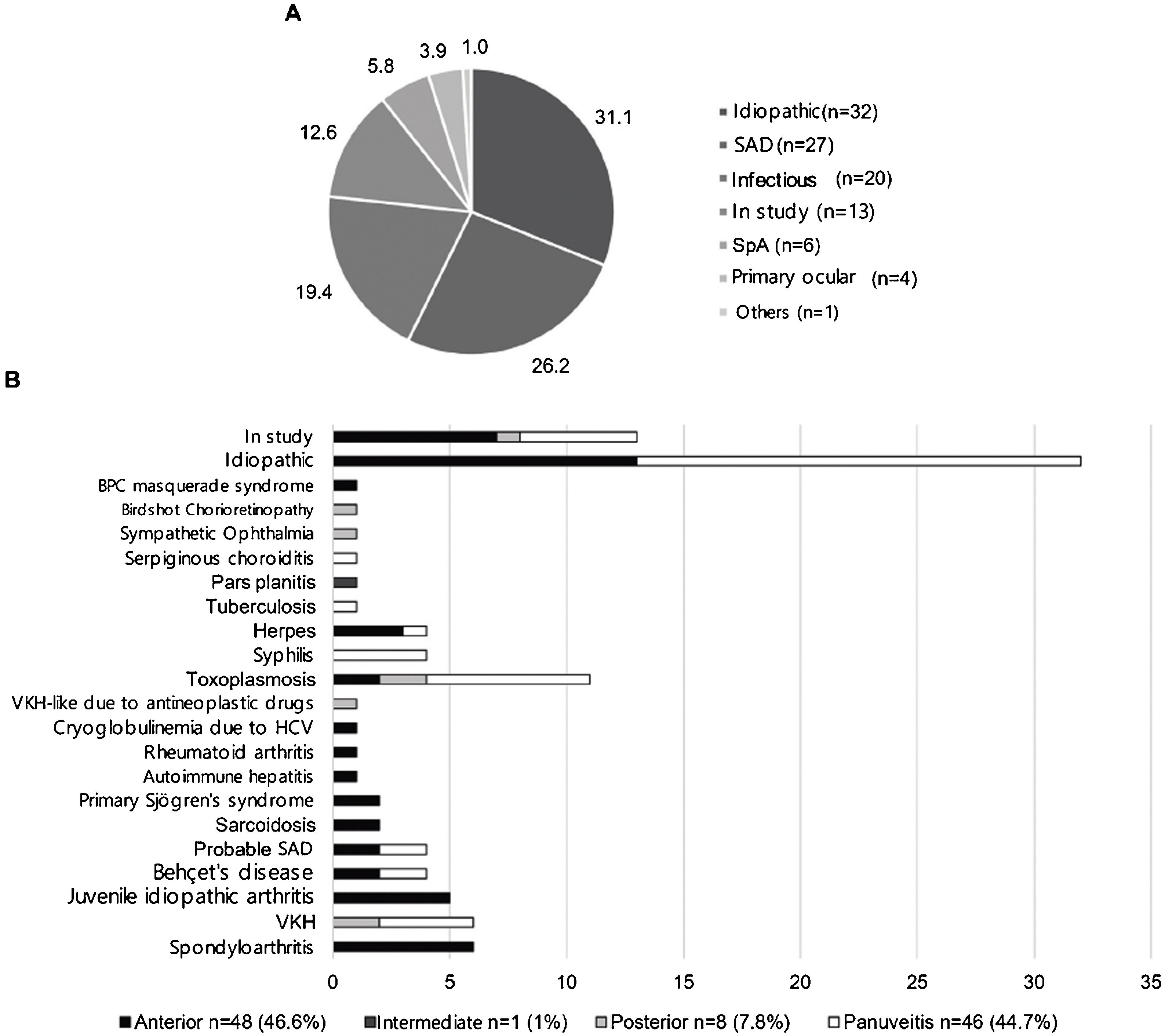

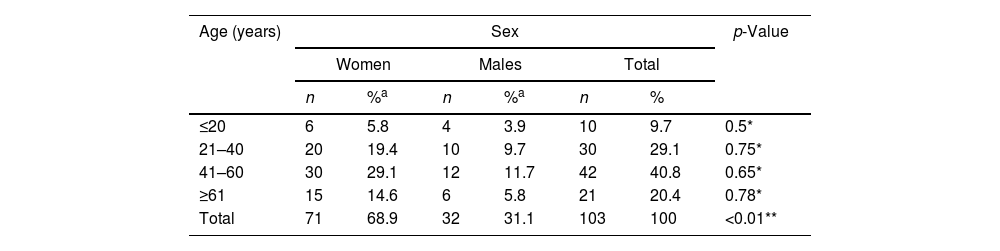

ResultsOne hundred and three patients were included, with a median age of 47 years, and 71 (68.9%; p < 0.01) were women. The anatomical classification was anterior uveitis 46.6%, intermediate 1%, posterior 7.8%, and panuveitis 44.7%. The etiology was identified in 58 (56.3%) patients, 32 (31.1%) were idiopathic and 13 (12.6%) were still under aetiological study. Systemic autoimmune diseases occurred in 26.2%, with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease being the most frequent (5.8%). Spondyloarthritis accounted for 5.8% of the cases. Infectious etiology was observed in 19.4%, with ocular toxoplasmosis predominant in 10.7%. Seventy-one percent of non-infectious uveitis required systemic immunosuppressive treatment, with methotrexate being the most used in anterior (46.4%) and intermediate (100%) uveitis and azathioprine in posterior (100%) and panuveitis (42.9%). Eight patients (13.6%) required the combination of ≥2 drugs; of them, 37.5% had anterior uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and 37.5% had idiopathic panuveitis.

ConclusionsThe etiology was established in more than half the patients with uveitis. The most frequent were ocular toxoplasmosis, VKH disease, and associated SpA disease. A high percentage of non-infectious uveitis required systemic immunosuppressive treatment, with methotrexate and azathioprine being the most used.

Por su asociación con enfermedades y tratamiento sistémicos, la uveítis requiere un abordaje multidisciplinario; no obstante, existen pocos estudios en unidades de uveítis en Latinoamérica.

ObjetivoDescribir las características clínicas y terapéuticas en pacientes con uveítis asistidos en la Unidad de Uveítis del Hospital de Clínicas Dr. Manuel Quintela de Montevideo, Uruguay.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional, descriptivo, transversal en pacientes ≥15 años, atendidos de octubre del 2018 a enero del 2020 con diagnóstico de uveítis.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 103 pacientes, con una mediana de edad de 47 años, y 71 (68,9%; p < 0,01) fueron mujeres. La clasificación anatómica fue: uveítis anterior 46,6%, intermedia 1%, posterior 7,8% y panuveítis 44,7%. La etiología se identificó en 58 (56,3%) pacientes, 32 (31,1%) fueron idiopáticas y 13 (12,6%) continuaban en estudio etiológico. Las enfermedades autoinmunes sistémicas se presentaron en el 26,2%, siendo más frecuente la enfermedad de Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (5,8%). Las espondiloartritis fueron el 5,8% de los casos. La etiología infecciosa se observó en el 19,4%, en tanto que la toxoplasmosis ocular predominó en el 10,7%. El 71,1% de las uveítis no infecciosas requirieron tratamiento inmunosupresor sistémico, siendo el metotrexate el más usado en uveítis anterior (46,4%) e intermedia (100%), y la azatioprina en uveítis posterior (100%) y panuveítis (42,9%). Ocho pacientes (13,6%) requirieron la combinación de ≥2 fármacos; de ellos, el 37,5% tuvo uveítis anterior asociada con artritis idiopática juvenil y el 37,5% presentó panuveítis idiopática.

ConclusionesSe logró establecer la etiología en más de la mitad de los pacientes con uveítis, siendo más frecuentes la toxoplasmosis ocular, la enfermedad de VKH y la asociada con SpA. Un alto porcentaje de las uveítis no infecciosas requirieron tratamiento inmunosupresor sistémico, siendo el metotrexate y la azatioprina los más utilizados.

Uveitis is the inflammation of the eyeball’s vascular layer, comprising the iris, ciliary body, and choroid, which may spread to adjacent structures. It has been estimated that an incidence of between 17 and 52 cases per 100,000 inhabitants/year and a prevalence of 38–714 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Its relevance lies in the fact that it can partially or totally compromise vision in up to 35% of patients, in addition to being the cause of between 10 and 25% of cases of legal blindness.1,2

Since, in about 50% of cases, it is possible to identify a systemic cause of uveitis, it is important to have a multidisciplinary approach.3 For this purpose, the Uveitis Unit of the Hospital de Clínicas Dr. Manuel Quintela, in Montevideo, Uruguay, was established, in which patients with uveitis are evaluated by a multidisciplinary team, composed of specialists in ophthalmology, internal medicine, and rheumatology, who work together in the same consultation. There are few studies of patients assisted in multidisciplinary units in Latin America, so the present work aims to describe the demographic, anatomical, and etiological characteristics and the systemic immunosuppressive treatment used in the unit.

MethodsAn observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study of patients assisted in the Uveitis Unit of the Hospital de Clínicas Dr. Manuel Quintela was conducted from October 1, 2018, to January 31, 2020. Patients aged 15 years or older with a diagnosis of uveitis confirmed by the unit’s ophthalmologists were included in the unit database, excluding cases in which one or more variables were not recorded, as well as patients with an isolated diagnosis of episcleritis, scleritis, or keratitis. The hospital’s research ethics committee authorized the study.

The initial ophthalmologic evaluation included ocular motility, best-corrected visual acuity, applanation tonometry, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, and fundoscopic exam. It was supplemented with optical coherence tomography, fluorescein angiography, campimetry, and ocular ultrasonography when necessary.

The anatomical classification, course, and degree of inflammation were carried out according to the recommendations of the International Uveitis Study Group (IUSG) of 1987 and the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group (SUN) of 2005.

All patients were asked for complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, blood glucose level, liver function panel, plasma urea level, serum creatinine test, urinalysis, serology for human immunodeficiency virus and Toxoplasma gondii, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory Test (VDRL), and chest X-ray.

Upon suspicion of disease associated with human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), their specific markers (HLA-B27, HLA-B51, and HLA-A29) were requested. A Mantoux test was ordered in cases of granulomatous uveitis and risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission. A polymerase chain reaction was solicited for the suspected microorganism and aqueous humor cultures upon suspicion of intraocular infection. In case of suspicion of ocular neoplasia, flow cytometry of the aqueous humor was performed.

Together with ophthalmologists, the patients were evaluated by internists and rheumatologists through anamnesis and physical examination, expanding the complementary assessments before suspicion of a systemic disease causing uveitis. Diagnoses of systemic autoimmune disease (SAD) were carried out considering the classification criteria established for each entity by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). Internationally validated criteria4 was used in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (VKH). The term “probable systemic autoimmune disease” was applied to patients with clinical and/or paraclinical features of autoimmune disease without meeting classification criteria for a specific entity. Uveitis of undetermined etiology, despite thorough evaluation, was considered idiopathic.

The information recorded in the database was analyzed by SPSS® software version 15. The results are presented in absolute, percentage, median, and range values, given the non-normal distribution of the sample, as measured by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The proportions were compared by Chi-squared and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

ResultsClinical Characteristics and Etiology of UveitisOf 103 patients included, 71 (68.9%; p < 0.01) were women, with a median age of 47 years (years: minimum 15, maximum 85, range: 70, interquartile range: 27) for both sexes, with no statistically significant differences by age groups (Table 1). 50.5% had bilateral uveitis, and 9 patients (8.7%) had unilateral amaurosis. Regarding the etiology, the cause was identified in 58 patients (56.3%).

Uveitis was acute in 39 (37.9%) patients, recurrent in 54 (52.4%), and chronic in 10 (9.7%), with a median progression from the first episode of uveitis to the date of inclusion in the 32-month study, with a minimum of 9 months, maximum of 477, range of 468 and interquartile range 63 (out of a total of 88 patients; lost values from 15 patients were not included in the statistical calculation). The time it took patients to be referred to the uveitis unit had a median of 2 months, minimum 0, maximum 276, range 276, and interquartile range 35 (out of a total of 87 patients; lost values from 16 patients were not included in the statistical calculation).

Fig. 1 details the distribution of patients according to topography and etiology. In descending order of frequency, the anatomical classification observed anterior uveitis in 48 (46.6%) patients, panuveitis in 46 (44.7%) patients, posterior uveitis in 8 (7.8%) patients, and intermediate uveitis in one (1.0%) patient. Anterior uveitis was mainly idiopathic (n = 13; 27.1% of anterior uveitis), followed by (at that time) continuing etiologic study (n = 7; 14.6% of anterior uveitis), spondyloarthritis (SpA) (n = 6; 12.5% of anterior uveitis), and juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) (n = 5; 10.9% of anterior uveitis). Panuveitis was also mostly idiopathic (n = 19; 41.3% of panuveitis), followed by ocular toxoplasmosis (n = 7; 15.2% of panuveitis). In the 6 SpA patients (5.8% of the total uveitis), 100% had anterior uveitis, and 83.3% showed HLA-B27 positive.

In the SAD group, the majority presented with anterior uveitis (JIA, sarcoidosis, primary Sjögren’s syndrome, autoimmune hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and hepatitis C virus-cryoglobulinemia). Patients with VKH disease had mostly panuveitis (n = 4; 66.7% VKH), followed by posterior uveitis (n = 2; 33.3% VKH). Patients with Behçet’s disease presented in equal proportion with panuveitis and anterior uveitis (n = 2; 50% Behçet’s disease, respectively).

In the case of infectious uveitis, most patients presented with panuveitis, except for herpetic uveitis, which mostly corresponded to anterior uveitis (n = 3; 75% of herpetic uveitis).

Uveitis and Systemic Immunosuppressive TreatmentAll patients were initially prescribed treatment with topical and/or oral glucocorticoid, cycloplegic mydriatics, and, if necessary, antimicrobials.

Of 83 patients with non-infectious uveitis, 71.1% were receiving systemic immunosuppressive therapy at the time of the study; methotrexate was the most commonly used in anterior (46.4%) and intermediate (100%) uveitis, while azathioprine predominated in posterior (100%) uveitis and panuveitis (42.9%). According to the etiology of uveitis, the most commonly used systemic immunosuppressants were anti-TNF drugs (60%) in SpA and azathioprine in SAD and idiopathic uveitis (40% and 33.3%, respectively). Cases requiring anti-TNF drugs for refractory uveitis were JIA (4 cases; adalimumab 50%, infliximab 50%), SpA (3 cases; 33.3% infliximab, 66.7% golimumab), and idiopathic bilateral panuveitis (one case; 100% adalimumab). The detail of the systemic immunosuppressants used at the time of the study, according to the topography and etiology of uveitis, is presented in Table 2.

Current systemic immunosuppressive treatment.

| Methotrexate | Azathioprine | Mycophenolate | Cyclosporine | Anti-TNF | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 19 | n = 20 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 8 | n = 59 | |

| According to the topography of uveitis | ||||||

| Anterior n (%) | 13 (46.4) | 6 (21.4) | 0 | 2 (7.1) | 7 (25.0) | 28 |

| Intermediate n (%) | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Posterior n (%) | 0 | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Panuveitis n (%) | 5 (17.9) | 12 (42.9) | 6 (21.4) | 4 (14.3) | 1 (3.6) | 28 |

| According to the etiology of uveitis | ||||||

| SpA n (%) | 2 (40.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (60.0) | 5 |

| SAD n (%) | 8 (32.0) | 10 (40.0) | 0 | 3 (12.0) | 4 (16.0) | 25 |

| Idiopathic n (%) | 8 (29.6) | 9 (33.3) | 6 (22.2) | 3 (11.1) | 1 (3.7) | 27 |

| Primary ocular n (%) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

The 59 patients included in this table received systemic immunosuppressive treatment at the time of the study.

Anti-TNF: anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody; SAD: systemic autoimmune disease; SpA: spondyloarthritis.

Of the 59 patients on systemic immunosuppressive therapy, 8 (13.6%) required the combination of 2 or more drugs (Table 3); of these, 3 of 8 (37.5%) had anterior uveitis associated with JIA, and another 3 of 8 (37.5%) had idiopathic panuveitis.

Patients requiring a combination of systemic immunosuppressants, according to topography, evolution, and etiology of uveitis.

| MTX | AZA | MMF | CyA | ADA | IFX | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Recurrent bilateral anterior uveitis due to JIA | ||||||

| 2 | Recurrent unilateral anterior uveitis due to JIA | ||||||

| 3 | Recurrent bilateral anterior uveitis due to JIA | ||||||

| 4 | Recurrent idiopathic bilateral anterior uveitis | ||||||

| 5 | Recurrent bilateral panuveitis due to Behçet’s disease | ||||||

| 6 | Recurrent idiopathic bilateral panuveitis | ||||||

| 7 | Chronic idiopathic bilateral panuveitis | ||||||

| 8 | Recurrent idiopathic bilateral panuveitis |

The boxes marked correspond to the combinations of immunosuppressants used. Abbreviations: MTX: methotrexate; AZA: azathioprine; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; CyA: cyclosporine; ADA: adalimumab; IFX: infliximab.

In the presented series, the majority were women in the middle ages of life, and the etiology was determined in more than half of the patients, similar to other studies carried out in Latin America and the world.5–12 Although the frequency of idiopathic uveitis was 31.1%, the 13 patients (12.6%) who were in the study stage at the time of being included until the completion of the present research work did not show a clear etiology, which would place them more likely within the group of idiopathic uveitis. Despite this, the frequency was similar to other studies, between 30 and 60% of idiopathic cases.12 The time taken for patients to be referred to the uveitis unit was much shorter than in other studies, which indicates an average of 2.1 years.13 These differences could be due to the small sample size, as well as the fluid communication between the staff of the uveitis unit and other specialist doctors, which makes it possible to shorten the reference times of patients.

As for the patterns of uveitis, recurrent ones predominated, followed by acute and chronic ones, similar to the Jódar-Márquez study (recurrent 50.5%, acute 33.9%, chronic 15.6%).14 The most frequent anatomical location was anterior uveitis (46.6%), followed very closely by panuveitis (44.7%), as reported in other tertiary care centers (anterior uveitis 25%–63%, panuveitis 9%–38%). Only one case (1%) of intermediate uveitis was observed, similar to other case series that indicate it as the least common form of uveitis (0%–19.3%).14 However, the frequency of posterior uveitis (7.8%) was observed well below that reported in other tertiary care centers in Latin America (Brazil 40.1%, Colombia 35.9%), where it becomes the first or second most frequent location8,9; differences that are due to the more significant number of cases of ocular toxoplasmosis reported by other countries.

In patients with identified etiology, SAD predominated (26.2%), including VKH (5.8%), followed by infectious causes (19.4%), with a predominance of ocular toxoplasmosis (10.7%). These findings coincide with other studies, in which the first cause of uveitis is due to ocular toxoplasmosis and the second to VKH, although in variable percentages. In Mexico, Tenorio observed 14.1% of patients with ocular toxoplasmosis and 7.9% with VKH, similar to the case series presented.11 Other studies report a much higher proportion of ocular toxoplasmosis (between 24 and 39.8%) than VKH (between 1.2 and 7.5%).8,10 This pattern is reversed in Amerindian populations in Chile, in which VKH disease predominates in 17.2% of cases, followed by ocular toxoplasmosis in 6.4%.7 These different percentages are due to the few cases of toxoplasmosis referred to this unit of uveitis but also show the importance of considering ethnic origin when raising the diagnosis of VKH disease, as well as the country of origin when endemic toxoplasmosis exists.

Regarding etiology and topography, some studies indicate that anterior and intermediate uveitis is mostly idiopathic,7,15 which differs partially from the presented case series, in which idiopathic uveitis debuted mostly as panuveitis or anterior uveitis. This difference can be partly explained by the low number of cases included, with one case of idiopathic intermediate uveitis (pars planitis).

SpAs with anterior uveitis and HLA-B27 positive were similar to the study in a multi-ethnic population in Spain, in which 6.7% of the total uveitis was associated with SpA, and of these, 91.7% presented anterior uveitis.16 However, another study with a smaller foreign population reported more cases of SpA (12.6%),15 approximately double the case series presented. Similarly, in the study by Juanola et al., patients with recurrent acute anterior uveitis associated with HLA-B27 had a higher frequency of axial SpA (71.2 vs. 19.5%; p < 0.0001) and peripheral SpA (21.9 vs. 11.1%; p < 0.0001) than HLA-B27 negative patients17; these differences could be partly explained by the heterogeneous prevalence of HLA-B27.

In SAD, anterior uveitis and panuveitis predominated, in agreement with other studies that indicate that the probability of finding a systemic disease is higher in these topographies.12

Ocular toxoplasmosis presented mostly (63.6%) as panuveitis. According to the findings presented, although ocular toxoplasmosis usually presents as retinochoroiditis, in Latin Americans, greater inflammatory activity has been reported, including the anterior chamber and the vitreous, so it is usually presented aspanuveitis.18

Systemic Immunosuppressive Treatment in UveitisThe requirement for immunosuppressants (71.1%) was higher than in other case series (49.9%).19 Having excluded infectious uveitis, these differences could be due to the complexity of the patients referred to this unit of uveitis and the early use of corticosteroid-sparing agents.

Methotrexate was most commonly used in anterior and intermediate uveitis, while azathioprine was most commonly used in posterior uveitis and panuveitis. Consistent with the results found, according to several subanalyses of the SITE study, effectiveness as a corticosteroid-sparing agent was most frequently achieved in anterior uveitis with methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil in intermediate uveitis with methotrexate and azathioprine, and in posterior uveitis/panuveitis with mycophenolatemofetil.20 Similarly, although it has shown particular effectiveness in intermediate uveitis, azathioprine is also effective in posterior uveitis and panuveitis, especially associated with Behçet’s disease or VKH.21 However, the choice of systemic immunosuppressive treatment depends not only on the topography of inflammation and effectiveness but also on safety and accessibility (a critical limitation in the hospital of the present study), among other factors.

The etiologies that required anti-TNF drugs for refractory uveitis were comparable with other studies, indicating their efficacy in uveitis associated with JIA, SpA, HLA-B27, and Behçet’s disease.22 Most studies support the use of adalimumab and infliximab, while golimumab has been studied mostly in refractory anterior uveitis associated with SpA.22–24

Patients who required two or more immunosuppressants had anterior uveitis or panuveitis, unlike that reported by Millán-Longo et al., in whose study 62%–65% of patients with intermediate, posterior uveitis or panuveitis required more than one immunosuppressant and only 46% with anterior uveitis required it.19 The most frequent combinations were an anti-TNF plus methotrexate in anterior uveitis associated with JIA and mycophenolate plus cyclosporine in idiopathic panuveitis. In this regard, the SYCAMORE study reported that in anterior uveitis associated with JIA, adalimumab plus methotrexate controlled inflammation with a lower failure rate than methotrexate alone.25 Regarding the use of infliximab in uveitis, some studies have shown improvement in long-term inflammation in monotherapy, while others showed more significant remission by associating cyclosporine or mycophenolate and preventing the formation of neutralizing antibodies, particularly with methotrexate.26 Similarly, according to Espinosa et al.'s treatment recommendations, there is no evidence to indicate an immunomodulator of choice in idiopathic panuveitis. However, methotrexate, mycophenolate, azathioprine, cyclosporine, sirolimus, and tacrolimus have shown potential efficacy, which can be changed, added, or scaled up to biological therapy.27

Strengths and LimitationsSeveral authors have highlighted the relevance of the joint care of patients with uveitis in multidisciplinary units, in which the ophthalmologist and the internist/rheumatologist with specific training in the area are central pieces, which is very useful to agree on diagnostic-therapeutic criteria, provide close collaboration with a reciprocal pedagogical nuance and achieve efficient, comprehensive care.3,28,29 However, there are few studies of patients with uveitis assisted in multidisciplinary units in Latin America, which stands out as a strength of the work presented, being the first experience of a multidisciplinary unit of uveitis in Uruguay and the first record of this pathology in the Uruguayan population.

The limitations of this study include the low number of patients included. In addition, being a tertiary care center for adult patients, the referred patients present greater diagnostic and/or therapeutic complexity, which is reflected in the low number of cases of anterior toxoplasmosis and uveitis and the high percentage of non-infectious uveitis that required systemic immunosuppressants, since they are generally cured by the ophthalmologist and only the ones with complex or systemic symptoms reach the uveitis unit. Similarly, it was not recorded the duration of episodes of uveitis, the use of topical and systemic corticosteroids, nor visual acuity are relevant given the visual complications due to association with glaucoma and optic nerve damage or cataracts, either due to treatment or due to the disease. Patient progress data may be evaluated in a subsequent study.

ConclusionsSimilar to other case series, anterior uveitis and panuveitis predominated, while, in contrast, cases of posterior uveitis were lower. The etiology was established in more than half of the patients with uveitis, the most frequent being ocular toxoplasmosis, VKH disease, and that associated with SpA. A high percentage of non-infectious uveitis required systemic immunosuppressive treatment, with methotrexate being the most commonly used in anterior and intermediate uveitis and azathioprine in posterior uveitis and panuveitis.

FinancingThe authors declare that they have not received funding to prepare this article.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest in preparing this article.