Breast milk is considered as a living ecosystem. Maternal, environmental and neonatal factors affect milk bacterial composition. The aim of present study was to assess the phyla from breast milk of mothers with vaginal delivery compared to the cesarean section. In this single-center case–control study, sixty women were participated. Half of them had vaginal delivery and others experienced cesarean section. The breast milk samples were collected three months after delivery for the DNA extraction to measure Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria using quantitative real time chain polymerase reaction. Daily intake of calories, protein, fat, carbohydrate and fiber did not differ significantly between the two groups. The proportion of Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria were significantly higher in milk of mothers with a cesarean section than the vaginal delivery (p=0.03, p=0.02 and p=0.042). Similarly, the Firmicutes to Bacteroides ratio was significantly increased (p=0.02). The Actinobacteria population was significantly higher in milk of vaginally-delivered mothers who had male infant than females (p=0.015). Breast milk of mothers with cesarean section showed alterations in the main bacterial phyla population compared to the vaginal delivery. Moreover, our results suggest that the sex of infant is an effective factor on some phyla quantity.

La leche materna se considera un ecosistema vivo. Factores maternos, ambientales y neonatales influyen en la composición bacteriana de la leche. El objetivo del presente estudio fue evaluar los filos presentes en la leche materna de madres con parto vaginal, en comparación con las que tuvieron parto por cesárea. En este estudio de casos y controles, realizado en un solo centro, participaron sesenta mujeres. La mitad tuvo parto vaginal y el resto, cesárea. Las muestras de leche materna se recolectaron tres meses después del parto para la extracción de ADN y la determinación de Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria y Proteobacteria mediante reacción en cadena de la polimerasa (PCR) cuantitativa en tiempo real. La ingesta diaria de calorías, proteínas, grasas, carbohidratos y fibra no difirió significativamente entre los dos grupos. La proporción de Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes y Proteobacteria fue significativamente mayor en la leche de madres con cesárea que en la de madres con parto vaginal (p=0,03; p=0,02 y p=0,042). De igual manera, la proporción de Firmicutes a Bacteroides aumentó significativamente (p=0,02). La población de Actinobacteria fue significativamente mayor en la leche de madres con parto vaginal que tuvieron hijos varones que en la de madres que tuvieron mujeres (p=0,015). La leche materna de madres con cesárea mostró alteraciones en la población de los principales filos bacterianos en comparación con las madres con parto vaginal. Además, nuestros resultados sugieren que el sexo del lactante influye en la cantidad de algunos filos.

Based on the recommendations from American Academy of Pediatrics and the World Health Organization, continued breastfeeding along with introducing appropriate complementary foods for up to 2 years or longer is suggested15. Human milk is a rich source of nutrients and bioactive compounds, including the antimicrobial proteins, lactoferrin, lysozyme, and some oligosaccharides4,7. It has now been proven that breast milk contains approximately 106 bacteria per ml, which plays an important role in colonizing the newborn's gut after the birth22,27. The composition of gut microbiota determines the maturity of infant's immune system. The innate immune system is the first and fastest defense against pathogens. The adaptive immune system begins to develop after birth. Interactions between maternal immune cells, antibodies and dietary antigens, as well as metabolites derived from the maternal microbiome, are key players in future defense10,20. Studies have been shown that the main microorganisms in breast milk are belonging to the Proteobacteria (Serratia, Pseudomonas, Ralstonia, Sphingomonas, Bradyrhizobium), Firmicutes (Streptococcus and Staphylococcus), and Actinobacteria (Propionibacterium, Corynebacterium) phyla. The microbial balance in breast milk during the first 100 days after birth plays a crucial role in health status at the adulthood1. Only a few cross-sectional studies have examined the effects of maternal body mass index (BMI) and mode of delivery on the composition of breast milk microbiota, which sampling were performed in different times of lactation from 1 week to 6 months postpartum13,29. Results of these few studies are also contradictory due to differences in sample collection and ethnicity of the studied population. A recent study reported that there is no significant association between the mode of delivery and maternal pre-pregnancy BMI with microbiota diversity in the breast milk25 however, another study showed a significant association12,17. Recently, it is reported that babies born by cesarean section have lower levels of Bacteroides, Escherichia, and Lactobacillus in the gut compared to babies born vaginally32. However, there is no study on the population of breast milk phyla, up to date. Considering the bacterial stabilization three months after delivery, the present study was designed to evaluate the population of four dominant phyla including Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria in the breast milk of mothers with cesarean section compared to the vaginal delivery. Diet and the type of food were also considered as the main influential factors.

Materials and methodsStudy participants and sample collectionIn the present case–control study, all methods were performed in accordance with the Helsinki guidelines and regulations. Eighty mother–infant pairs were enrolled. Half of them had cesarean section and others vaginally delivered. Mothers aged 18–40 years, exclusively breastfeeding, who had single birth were followed to three months of lactation. Sample representativeness was performed by the cluster sampling method, which collected samples from all area of the city to assimilate economic, social and cultural properties in the selected participants. All of labors were performed in the educational-therapeutic hospital, Ayatollah Mousavi Center, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran. Participants, who were not smoker, addict, or alcohol/drugs consumers were included. Participants were grouped based on the mode of delivery. Participants were included in study after obtaining oral, written informed consent and based on the inclusion criteria. Participants who consumed probiotic, prebiotic, symbiotic or antibiotics during the past two months were excluded. Participants with any type of chronic diseases including type 1 or 2 diabetes, renal, kidney, heart, immune, psychiatrics and thyroid disorders not included in the study. Participants with any type of gastro-intestinal disorder including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, celiac or mal-absorptive and inflammatory situation were excluded. Women who had preterm labor did not include. Lactating women with a history of gestational diabetes (GDM) or pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) not included. Mothers with small and large newborns for gestational age were excluded. After three months, only sixty participants cooperated to sampling. The breast milk samples were collected in morning at the health center after washing and sterilizing the hands, cleaning the nipples and the surrounding areas with chlorhexidine 2% solution prior to collecting. All samples were collected from both breasts, manually in a sterile falcon. Before the DNA extraction, all samples were centrifuged at 5000rpm for 20min for fat separation and were stored at −75°C for three months to final analysis. The study diagram has been summarized in Figure 1.

Demographic, dietary and anthropometric assessmentMaternal age, education, infant's anthropometric indices including the weight, height, head circumference, and gender were recorded. Anthropometric measures were recorded using a calibrated Seca scale, which is done by a trained nutritionist using a standard method. A 169-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was completed for all participants, validated by a three-day food record (two regular days and one holiday). A calibrated Seca baby scale (Harlow Healthcare, London, UK) and a standard Harpenden infantometer (Harlow Health Care, London, UK) were used to the last 0.1kg and 0.5cm to measure weight and height of infants6. Head circumference was measured by a flexible metal tape measure from the most prominent part of the forehead (1–2 fingers above the eyebrow) around to the widest part of the back of the head2.

DNA extraction and polymerase chain reactionDNA was extracted by a kit (Qiagen Co., Germany) based on the manufacturer's instructions. To sample preparation, 200-μl milk sample, 200-μl binding buffer and 40-μl proteinase K were added to a 1.5ml micro centrifuge tube, mixed immediately at 70°C for 10min. Then, 100-μl isopropanol was added and mixed well. Samples were centrifuged at 8000rpm for 1min, after purification through filter inserted to collection tubes. Filter tubes were combined in a new collection tube and 500-μl inhibitor removal buffers was added to the upper reservoir and centrifuged at 8000rpm for 1min. The last step was repeated twice by adding 500-μl washing buffer. After discarding the flow through, the entire high pure assembly was centrifuged for 10s at full speed. To exclude the DNA, filter tube was inserted to a sterile 1.5ml micro centrifuge tube; 200-μl pre-warmed elution buffer was added and centrifuged at 8000rpm for 1min. The DNA quality was examined by running a small amount on the agarose gel and concentration of the extracted DNA was determined by a Nano drop spectrophotometer. The extracted DNA was kept in −20°C refrigerator to final analysis.

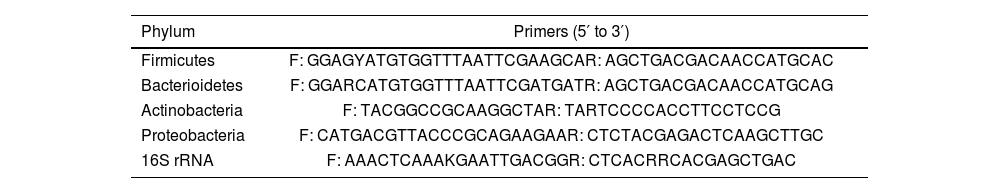

DNA amplification of 16S rRNA gene was done by qPCR method using universal bacterial primers that is presented in Table 1.

Primer sequence of each phylum.

| Phylum | Primers (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| Firmicutes | F: GGAGYATGTGGTTTAATTCGAAGCAR: AGCTGACGACAACCATGCAC |

| Bacterioidetes | F: GGARCATGTGGTTTAATTCGATGATR: AGCTGACGACAACCATGCAG |

| Actinobacteria | F: TACGGCCGCAAGGCTAR: TARTCCCCACCTTCCTCCG |

| Proteobacteria | F: CATGACGTTACCCGCAGAAGAAR: CTCTACGAGACTCAAGCTTGC |

| 16S rRNA | F: AAACTCAAAKGAATTGACGGR: CTCACRRCACGAGCTGAC |

Primers were verified in the primer-BLAST database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). ABI Step-One sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, California, USA) was used for the real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Micro tubes (20μl) were used, with 10-μl of SYBR Green Master Mix (Amplicon, Denmark), 4μl of DNA template, and 1μl of each forward and reverse primer. The free DNA and RNA purified water (4.5-μl) was added. 16SrRNA was used as the positive control in each run and a blank (purified water free of DNA and RNA) was added for each bacterial phylum. The cycle threshold (CT) values were normalized against 16SrRNA as a negative control. The initial denaturation included one cycle: 95°C for 10min. The amplification profile included 40 three-step cycles, including denaturation, annealing, and extension steps: 95°C for 30s, 60°C for 30s and 72°C for 30s. The final extension was provided in one cycle: 72°C for 30s. The results were generated and analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Sample size and statistical analysisTo determine bacterial phyla variation between mothers with cesarean section compared to vaginal delivery, considering the power of 80% and type 1 error, based on the previous study5, thirty participants were determined in each group. Dietary information was inserted into the N4 software (Nutritionist 4, USA). All dietary intakes converted to grams per day and data transferred to SPSS software, version 18. The Kolmogorov–Smirnoff test was used to assess the distribution form of data. In the normal distributed data, an independent sample t-test was used to determine differences between the two groups. However, non-parametric tests were used for the non-normal distributed data. Qualitative variables were compared by the chi2 square test. A linear mixed model was used to determine the effect of each assessed parameter on the bacterial population.

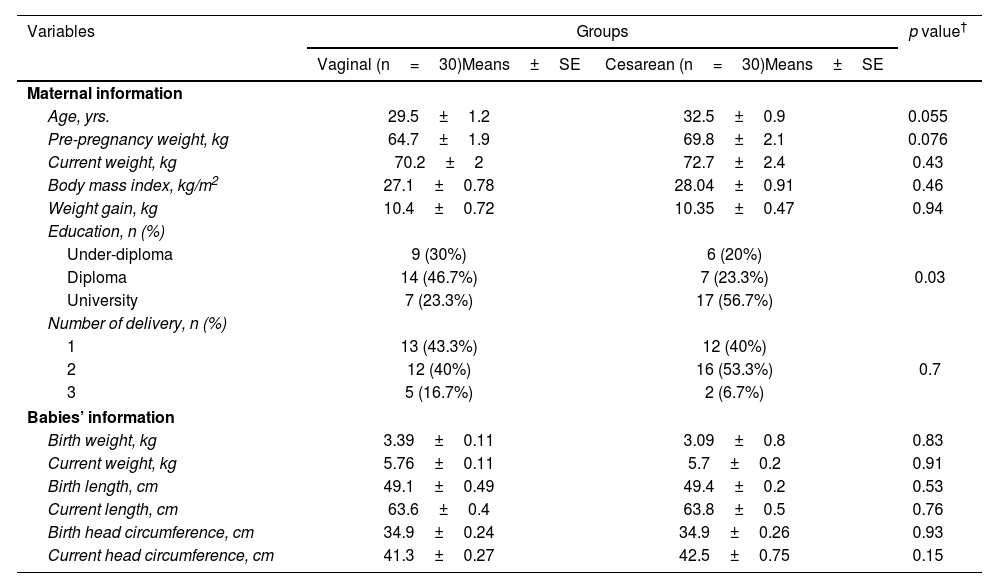

ResultsThirty women with cesarean section and thirty-one women with vaginal delivery were included in the present study. The baseline information of the participants has been shown in Table 2. The mean age of participants had no significant difference between the two groups. Other baseline information including pre-pregnancy weight, the current weight, and weight gain during pregnancy and growth indices of the newborns also did not show a statistically significant difference. A statistically significant difference was observed in educational level that more than 50% of participants in the cesarean section group had a university education, while in the vaginal delivery group, nearly half of the participants had a high school diploma (p=0.03). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of the number of deliveries and the sex of infants.

Demographic information of mothers and infants of the studied groups.

| Variables | Groups | p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal (n=30)Means±SE | Cesarean (n=30)Means±SE | ||

| Maternal information | |||

| Age, yrs. | 29.5±1.2 | 32.5±0.9 | 0.055 |

| Pre-pregnancy weight, kg | 64.7±1.9 | 69.8±2.1 | 0.076 |

| Current weight, kg | 70.2±2 | 72.7±2.4 | 0.43 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.1±0.78 | 28.04±0.91 | 0.46 |

| Weight gain, kg | 10.4±0.72 | 10.35±0.47 | 0.94 |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| Under-diploma | 9 (30%) | 6 (20%) | 0.03 |

| Diploma | 14 (46.7%) | 7 (23.3%) | |

| University | 7 (23.3%) | 17 (56.7%) | |

| Number of delivery, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 13 (43.3%) | 12 (40%) | 0.7 |

| 2 | 12 (40%) | 16 (53.3%) | |

| 3 | 5 (16.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Babies’ information | |||

| Birth weight, kg | 3.39±0.11 | 3.09±0.8 | 0.83 |

| Current weight, kg | 5.76±0.11 | 5.7±0.2 | 0.91 |

| Birth length, cm | 49.1±0.49 | 49.4±0.2 | 0.53 |

| Current length, cm | 63.6±0.4 | 63.8±0.5 | 0.76 |

| Birth head circumference, cm | 34.9±0.24 | 34.9±0.26 | 0.93 |

| Current head circumference, cm | 41.3±0.27 | 42.5±0.75 | 0.15 |

Dietary intake of participants from delivery to sampling showed no significant difference between the two groups (Table 3).

Dietary intake of participants per day.

| Variables | Groups | p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal (n=30)Means±SE | Cesarean (n=30)Means±SE | ||

| Energy, kcal/d | 2702.2±117.9 | 2650.1±139.5 | 0.77 |

| Protein, g/d | 102.1±6.7 | 96.6±3.8 | 0.47 |

| Carbohydrates, g/d | 327.3±20.4 | 346.8±14.4 | 0.43 |

| Total fat, g/d | 109.1±7.1 | 119.8±13.2 | 0.47 |

| Fiber, g/day | 51.8±3.1 | 49.7±4.3 | 0.69 |

The relative abundance of each phylum has been shown in Table 4. As seen, women who delivered by cesarean section had higher Bacteroidetes in their milk compared to women who delivered vaginally (p=0.03). Moreover, the Firmicutes population was significantly higher in milk of mothers with cesarean section than the vaginally delivered (p=0.01). The Proteobacteria abundance significantly increased in milk of mothers with cesarean section (p=0.04). The level of Actinobacteria did not show a significant difference between the two groups. The Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio was significantly higher in milk of mothers with cesarean section than the vaginal delivery (p=0.02).

Level of the assessed phylum (log CFU/ml milk) in the vaginal vs. cesarean section. Results are reported as mean±standard deviation.

| Variables | Groups | p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal (n=30) | Cesarean (n=30) | ||

| Bacteroidetes | 1.5±0.45 | 2.9±0.45 | 0.03 |

| Firmicutes | 1.5±0.49 | 4.3±1.2 | 0.01 |

| Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio | 1±1.08 | 1.5±2.7 | 0.02 |

| Actinobacteria | 1.84±0.33 | 3.5±0.97 | 0.2 |

| Proteobacteria | 1.32±0.34 | 2.93±0.71 | 0.04 |

Bold values shows significant difference between the two groups.

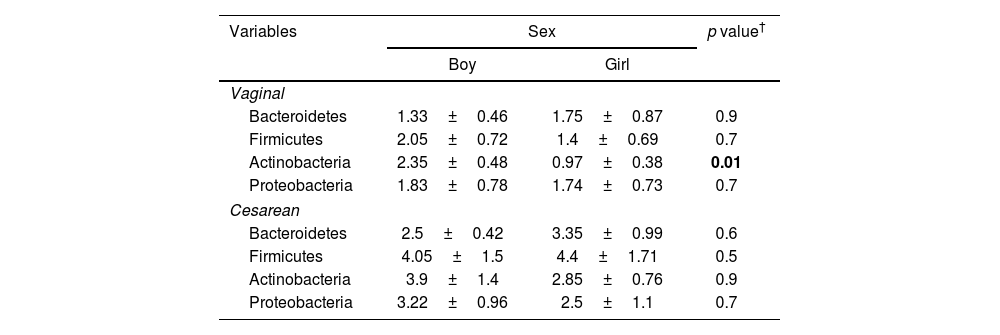

The relative abundance of the assessed phylum analyzed in milk of mothers with cesarean section and vaginal delivery by sex. In the cesarean section, no significant difference was observed in any assessed phylum between girls and boys. However, in the vaginally delivered mothers Actinobacteria population was significantly higher in milk of mothers with boy baby than the girl (p=0.01) (Table 5).

Level of the assessed phylum (log CFU/ml milk) in the vaginal and cesarean section, separated by sex. Results are reported as mean±standard deviation.

| Variables | Sex | p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boy | Girl | ||

| Vaginal | |||

| Bacteroidetes | 1.33±0.46 | 1.75±0.87 | 0.9 |

| Firmicutes | 2.05±0.72 | 1.4±0.69 | 0.7 |

| Actinobacteria | 2.35±0.48 | 0.97±0.38 | 0.01 |

| Proteobacteria | 1.83±0.78 | 1.74±0.73 | 0.7 |

| Cesarean | |||

| Bacteroidetes | 2.5±0.42 | 3.35±0.99 | 0.6 |

| Firmicutes | 4.05±1.5 | 4.4±1.71 | 0.5 |

| Actinobacteria | 3.9±1.4 | 2.85±0.76 | 0.9 |

| Proteobacteria | 3.22±0.96 | 2.5±1.1 | 0.7 |

Bold values shows significant difference between the two groups.

There are many concerns about bleeding, infection, sepsis, venous thrombosis, and endotoxemic shock, and increased length of hospital stay after cesarean section in mothers3,19,23,26. However, studies on the molecular alterations occurred after cesarean section is scarce. The present study was conducted on the predominant phylum found in the breast milk of mothers who delivered vaginally compared to mothers with cesarean section. Age, maternal BMI, maternal weight gain during pregnancy, and daily dietary intake had no significant difference between the two groups. Only educational level of mothers showed a significant difference. Analysis of milk phylum showed that mothers who delivered by cesarean section had higher population of Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria in their milk compared to mothers who delivered vaginally. The Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio is a mark of gut dysbiosis that is increased in milk of mothers with cesarean section. Moreover, we observed that the milk bacterial population depends on the infant's sex in vaginally delivered mothers. The Actinobacteria population was significantly higher in milk of mothers with boys. Our results are in agree with a previous report about differences between male and female infants in terms of contribution to the human milk microbiome based on the retrograde inoculation hypothesis24. Some animal studies demonstrated a functional role of sex in gastrointestinal transit time, visceral sensitivity, and hormone-dependent effects on gut physiology which propose a probable effect sex-related hormones on microbiota composition already at very early stage of life14,18. Results of a study which was analyzed the stool samples of neonates during the first month of life, showed that males had a lower alpha-diversity compared to females. Moreover, higher abundance of Clostridiales (Firmicutes), and lower abundance of Enterobacteriales (Proteobacteria) was observed9. Both intrinsic influence the intestinal phylum and extrinsic factors, including host physiology and genetics, health and disease status, antibiotic use, and diet29. Since diets vary geographically, the populations of Bacteroidetes also vary between various areas. In Asia, populations of these bacteria are lower due to higher carbohydrate intake compared to fat and protein8. However, the different genera of Bacteroidetes also vary between populations. The populations of Bacteroidetes spp. were higher in the gut of Japanese compared to the Indians because the Japanese consumed more meat-based foods, while Indians consumed more plant-based foods in their diets31. The Bacteroidetes is a phylum in the gut and milk, comprising the families Sphingobacteriaceae, Bacteroides, Proteobacteriaceae, and Tenerellacea. These bacteria have many health benefits when present in the intestine, but their transfer to other tissues can lead to their pathogenicity16. Transfer could be made by immune system disorders, leaky gut (loss of intestinal integrity), surgical trauma, and excessive use of antibiotics11. Results of a previous study showed that cesarean section leads to dysbiosis in the milk phylum. The sample size and the evaluated month of breastfeeding were different from those of our study. Moreover, food intake was not assessed in the mentioned study21. In our study, the population of Bacteroidetes in the milk of mothers with cesarean section increased, with may be one of the reasons for why these bacteria become pathogenic if they migrate into the breast milk. An increase in the population of Bacteroidetes in the intestine is beneficial for health, and their entry into other places that are sterile can have an adverse effect on health and turn them into pathogenic bacteria. Due to the thin mucosal layer of the small intestine, this destruction leads to the entry of some pathogens into other tissues. In addition, Bacteroidetes spp. impart resistance genes to other bacteria, which leads to resistance of these pathogens in extraintestinal sites21. At the beginning of the migration of these bacteria to extraintestinal sites, aerobic bacteria grow and damage the tissue. Then, redox reactions that require oxygen decrease and anaerobic bacteria such as Bacteroidetes begin to grow and lead to inflammation, diarrhea, and intra-abdominal abscess formation30. Therefore, accumulation of Bacteroidetes in sites other than the intestine can lead to bacteremia and abscess formation in other organs and even in the central nervous system28. However, controversial results have been reported in previous studies21. Some studies showed the beneficial effects of this phylum on health status but others showed negative impacts22,28. One of the most important reasons for these controversies is the different samples. Studies to date have examined stool samples, not breast milk. Changes in the breast milk phylum have different health outcomes than the fecal alterations. In a prospective study, the gut microbiome of babies born through cesarean section was compared to vaginal. Fecal samples were collected on days 5, 8, 11, and at weeks 2, 4, 6, 7 and at months 2 and 3 after delivery. Results showed that the proportion of Bacteroidetes and Parabacteroids in the feces of cesarean section decreased, while the population of Enterococcus, Klebsiella, Clostridium sensu, Villonella and Clostridium increased. Interestingly, in this study, the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes in the feces of infants born by cesarean section increased. The method of delivery affects the composition of the infant's gut microbiome, making them susceptible to a variety of chronic diseases, including type 1 diabetes, obesity, asthma, allergies, and various nervous system disorders30. The growing rate of cesarean delivery could be reduced by providing scientific educational information to doctors and patients. Based on the literature review, no study has fundamentally evaluated the composition of the phylum in milk of mothers with cesarean section compared to vaginal delivery in Iran. The results from the present study show that cesarean section seems to increase the population of opportunistic or deleterious phyla in breast milk compared with samples from vaginal deliveries. Similar to all other studies, the present study has advantages and limitations. One of the most important advantages of the present study is that all participants lived in the same city and their dietary intake did not differ significantly. Carbohydrates and fiber are among the most important macronutrients affecting the milk and intestinal phylum population that were similar between the two groups. The mothers’ BMI before pregnancy and weight gain during pregnancy were similar. All mothers breast-fed their babies. None of the mothers had metabolic events and disorders during pregnancy, including hypertension, blood sugar disorders, preeclampsia, etc. Therefore, the present study has eliminated confounding factors that could affect the milk phylum. However, one of the limitations of the present study is that only the bacterial phylum was examined, and due to lack of funding, it was not possible to examine the family and genus of bacteria. It is recommended that future studies with larger sample sizes assess the genera of the investigated phyla.

ConclusionsPopulation of Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria were significantly higher in breast milk of mothers with cesarean section, three months after delivery. Moreover, in the vaginally delivered mothers, Actinobacteria population was significantly higher in milk, of mothers with boy than girls. Actinobacteria includes some beneficial genera such as Bifidobacterium, recognized for their probiotic properties. Our results suggested that the population of this beneficial microbiota depends on sex of infants. More studies with larger sample size in different month of lactation around the world are needed to reach concise results.

Ethical approvalThe present study was ethically approved by the ethical committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences under the code of IR.ZUMS.REC.1402.139.

FundingNo funding was received. The present study was extracted from a M.D. thesis of a student in Zanjan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of interestNo conflict of interest to declare.

AcknowledgmentAuthors are very thankful from all participants.

Data availabilityData will be available based on a request to the corresponding author by e-mail.