The pathogenesis of non-organic anorexia in children is not clear. This study intends to analyze intestinal bacteria to provide a relevant theoretical basis for the clinical rational selection of microecological agents. In the present study, children with non-organic anorexia were included in the anorexia group and normal healthy children in the control group. Stool samples were collected for the bioinformatics analysis after PCR and high-throughput sequencing. The results showed that the Ace, Chao, and Shannon indexes in the anorexia group were higher than those in the control group, while the Simpson index in the control group was lower than in the anorexia group. There were 14 taxa in the anorexia group and 11 taxa in the healthy control group at the phylum level, and 193 taxa in the anorexia group and 180 in the control group at the genus level. The dominant bacteria at the phylum level of the two groups were the same, while there were 16 dominant bacteria taxa in the anorexia group and 17 in the control group at the genus level. The ratio of percentage abundance of Bacteroidetes to that of Firmicutes (the B/F index) in the anorexia group was higher than in the control group. The abundance of Bacteroidetes in the anorexia group was higher than that in the control group, and the abundance of Actinomycetes in the control group was higher than that in the anorexia group. There were significant differences in 14 dominant genera between the two groups at the genus classification level. The LEfSe multilevel species difference analysis showed that at the phylum level, the significant influential bacterial taxa in the anorexia group were Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria in the control group. At the genus level, the significant influential bacterial taxa in the anorexia group were Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium, and Subdoligranulum, and Bifidobacterium, Blautia, Streptococcus, Lachnoclostridium, and Erysipelatoclostridium in the control group. We conclude that the increase in Bacteroides abundance or in the B/F index and the reduction in Bifidobacterium abundance were related to the pathogenesis of anorexia.

La patogénesis de la anorexia no orgánica en los niños no está clara. El propósito de esta investigación fue estudiar las bacterias intestinales, y proporcionar una base teórica para la selección racional de probióticos en la clínica. Se analizaron muestras fecales de un grupo de niños con anorexia no orgánica (grupo de anorexia), y de un grupo de niños sanos normales (grupo de control). Se realizó PCR y secuenciación de alto rendimiento, seguido del análisis bioinformático. En el grupo de anorexia, los índices Ace, Chao y Shannon fueron más altos que en el grupo control, mientras que el índice Simpson fue menor. Se detectaron 14 taxones en el grupo de anorexia y 11 taxones en el grupo control a nivel de phylum. A nivel de género, hubo 193 taxones en el grupo de anorexia y 180 taxones en el grupo control. A nivel de phylum, las bacterias dominantes fueron las mismas en ambos grupos, mientras que, a nivel de género, hubo 16 taxones bacterianos dominantes en el grupo de anorexia y 17 taxones bacterianos dominantes en el grupo control. La relación entre el porcentaje de abundancia de Bacteroidetes y el porcentaje de abundancia de Firmicutes en el grupo de anorexia (índice B/F) fue mayor que en el grupo control. El número de Bacteroidetes en el grupo de anorexia fue mayor que en el grupo control, mientras que el número de actinomicetos fue mayor en el grupo control. Hubo diferencias significativas entre los dos grupos en 14 géneros dominantes. El análisis de la diferencia de especies multinivel (LEfSe) mostró que a nivel de phylum, Bacteroidetes fue el taxón bacteriano significativamente afectado en el grupo de anorexia, en tanto que en el grupo control lo fue Actinobacteria. A nivel de género, los taxones bacterianos que tuvieron un efecto significativo en el grupo de anorexia fueron Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium y Subdoligranulum, mientras que en el grupo control fueron Bifidobacterium, Blautia, Streptococcus, Lachnoclostridium y Erysipelatoclostridium. Nuestra conclusión es que el aumento de la abundancia de Bacteroides o del índice B/F y la reducción de la abundancia de Bifidobacterium se asocian con la patogénesis de la anorexia.

Non-organic anorexia (referred to as anorexia), mostly studied in China but not in many other countries, is a nutritional disorder that differs from anorexia nervosa, the former being more common in children younger than 10 years old, and the latter often occurring in children older than 10 years old with neurological and/or psychological abnormalities5,6. Anorexia can cause conditions and diseases such as malnutrition, anemia, rickets, hypoimmunity, and recurrent respiratory tract infections. It not only causes delays in growth and development, including mental development, and affects the nutritional status of children but also profoundly and adversely influences the physical health of adults15, thereby causing a heavy psychological and financial burden on the family, nation, and society. Therefore, it is particularly important to understand the pathogenesis of anorexia to be able to apply practical and effective treatments.

Previous studies have shown a dysregulation of the gut microbiota in children with anorexia, and the effective rate of treatment with microecological agents can reach 87.5%. However, most studies used culture methods to identify bacteria, while 99% of the bacteria present in nature cannot be cultured. A few studies used the specific PCR method. Nevertheless, these results could not comprehensively reflect the composition of the gut microbiota in children with anorexia. At the same time, previous studies have shown that probiotics alone or in combination with conventional therapies can be ineffective in the treatment of anorexia in children in 5.0–22.5% of cases, indicating that changes in the gut microbiota in children with anorexia may not be the only contributing factor, and precise treatment should be applied after understanding specific changes11,19,30.

Therefore, this study used a molecular biology method to select gene fragments in the conserved V3 region of bacterial 16SrDNA genes to design primers and investigate the gut microbiota in children with anorexia using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and high-throughput sequencing to test and conduct a comprehensive analysis of the intestinal microbiota of anorexic children, to then provide a theoretical basis for the selection of clinically feasible probiotics and perform subsequent drug intervention experiments28.

Materials and methodsStudy subjectsChildren with non-organic anorexia, who were treated in our Pediatric Health Care Center from May to October 2016, were included in the anorexia group (A), while healthy children were included in the control group (C). Observation charts were designed and used to record clinical data, including the name, sex, age, height, weight, dietary habits, and medical history of the subjects.

The diagnostic criteria of anorexia were as follows: (1) a long-term loss of appetite, indifference toward food, inappropriate feeding, an improper diet, or a history of disorders after an illness, such as an eating time ≥39min, food intake reduced by more than 1/3–1/2 compared to that before the disease onset, and a disease course over 1 month; (2) slow or no weight gain; and (3) non-organic diseases, genetic metabolic diseases, anorexia nervosa, and infection20.

The inclusion criteria for the anorexia group required: (1) meeting the diagnostic criteria for anorexia. (2) No history of infection within the past week. (3) No antibiotics or gastric motility drugs used within one week before enrollment. (4) No functional or organic diseases. (5) Diseases not involving any mental or drug-related effects. (6) Age ranges from 1 to 6 years old. The inclusion criteria for the control group required meeting the conditions mentioned in sections 2–6 above.

Sample collectionThe external genital area of each examined child was cleaned using an aseptic method before collecting a stool sample (5–10g). Each sample was placed into a presterilized collection tube. Each tube was labeled with the name of the child and the sample number before being stored at −20°C for later use22.

Extraction of bacterial DNA from stool samplesBacterial DNA was extracted from the stool samples (500mg each) using the QIAamp stool mini kit (Qiagen, Germany), in accordance with the instruction manual22.

Amplification of the V3–V4 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA geneThe sequence of the forward primer 338F was 5′-ACTCCTRCGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′, and that of the reverse primer 806R was 5′-GGACTACCVGGGTATCTAAT-3′. Sequencing adapters A (5′-GCCTCCCTcGCGCCATCAG-3′) and B (5′-GCCTTGCCAGCCCGCT CAG-3′) and barcodes were added to both ends of the primers. The amplification procedure was as follows: predenaturation at 94°C for 3min; 25 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30s, annealing at 55°C for 30s, and extension at 72°C for 30s, followed by incubation at 16°C for 10min. Each sample was amplified in triplicate. The length of each amplification product was approximately 400bp. After the amplification products were confirmed by l% agarose gel electrophoresis, the triplicate samples of the amplification products were mixed and subjected to 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The PCR products were recovered from the gel as per the instruction manual for the agarose gel DNA purification kit Ver. 2.0 (TaKaRa, China), then quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 microvolume UV spectrophotometer, and thoroughly mixed for later use17,22.

Emulsion PCR (emPCR) amplification and high-throughput sequencing (454 pyrosequencing)After the well-mixed PCR fragments were denatured and purified, each single-stranded DNA fragment with a unique-sequence was ligated to magnetic beads. The DNA fragment was then emulsified and amplified using the GS FLX titanium emPCR kit (Roche, USA). As a result, each magnetic bead contained millions of unique-sequence DNA clusters. After the emulsion was broken, the double-stranded DNA was denatured, and each magnetic bead contained unique-sequence, single-stranded DNA clusters. Magnetic beads and sequencing reagents were placed on a Pico titer plate containing 3.5 million wells made of optical fibers for detection. The sequence information was read based on the optical signals released upon oxidation of luciferin by pyrophosphate during base pairing17,22.

Bioinformatics analysis17,22High-quality optimized sequences were filtered from the original sequences, obtained by sequencing, using barcodes and primers and were truncated to an even length (150bp). Then, the SILVA tool was used for comparison, and sequences were clustered to generate operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with similarities greater than 97%.

The bacterial sequences were compared to the 16S rRNA sequence data available in GenBank and the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) to obtain the taxonomic information. Afterwards, all the sequences in each OTU were compared to find the closest taxa for a particular OTU.

Based on the data table in the tax_summary_a folder, the R language tools were used to plot the taxa composition and community composition. Hierarchical clustering was performed based on the distance matrix between samples.

Statistical analysisWeight/height index was used for the evaluation of the children's physical growth and the fifth division method was adopted35. When weight/height is below P3, it is considered low-grade malnutrition; when the value is between P3 and P25, it is considered middle and lower class. When the value is between P25 and P75, it is considered middle class; when the value is between P75 and P97, it is considered middle and higher class, and when the value is higher than P97, it indicates high-grade obesity.

Data with a normal distribution were expressed as x¯±s. Comparisons between the two groups were performed using the unpaired samples t-test. The rank-sum test was used when the variance was heterogeneous after calibration. Data without a normal distribution were expressed as P50 (P25−P75) and analyzed using the rank-sum test, a non-parametric test method.

a=0.05, p<0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference.

ResultsClinical dataA total of 24 pediatric patients and 25 healthy children were included in the study. The clinical data are shown in Table 1. There were no differences in age and gender between the anorexia group and the control group. The children were not obese. The weight/height level of the anorexia group was medium to low, and that of the control group was medium. After the statistical analysis, it was found that the weight/height level of the anorexia group was lower than that of the normal group.

α-Diversity analysisFigure 1 shows that the Ace, Chao, and Shannon indexes in the anorexia group were higher than those in the control group, while the Simpson index was lower in the control group than in the anorexia group.

β-Diversity analysisTaxa composition analysisThe bacterial composition number of the anorexia group at the phylum, class, order, family, and genus levels was 14, 24, 36, 66, 193, and in the control group was 11, 21, 30, 59, 180. The number of the same bacterial compositions in the two groups was 11, 20, 28, 55, 169.

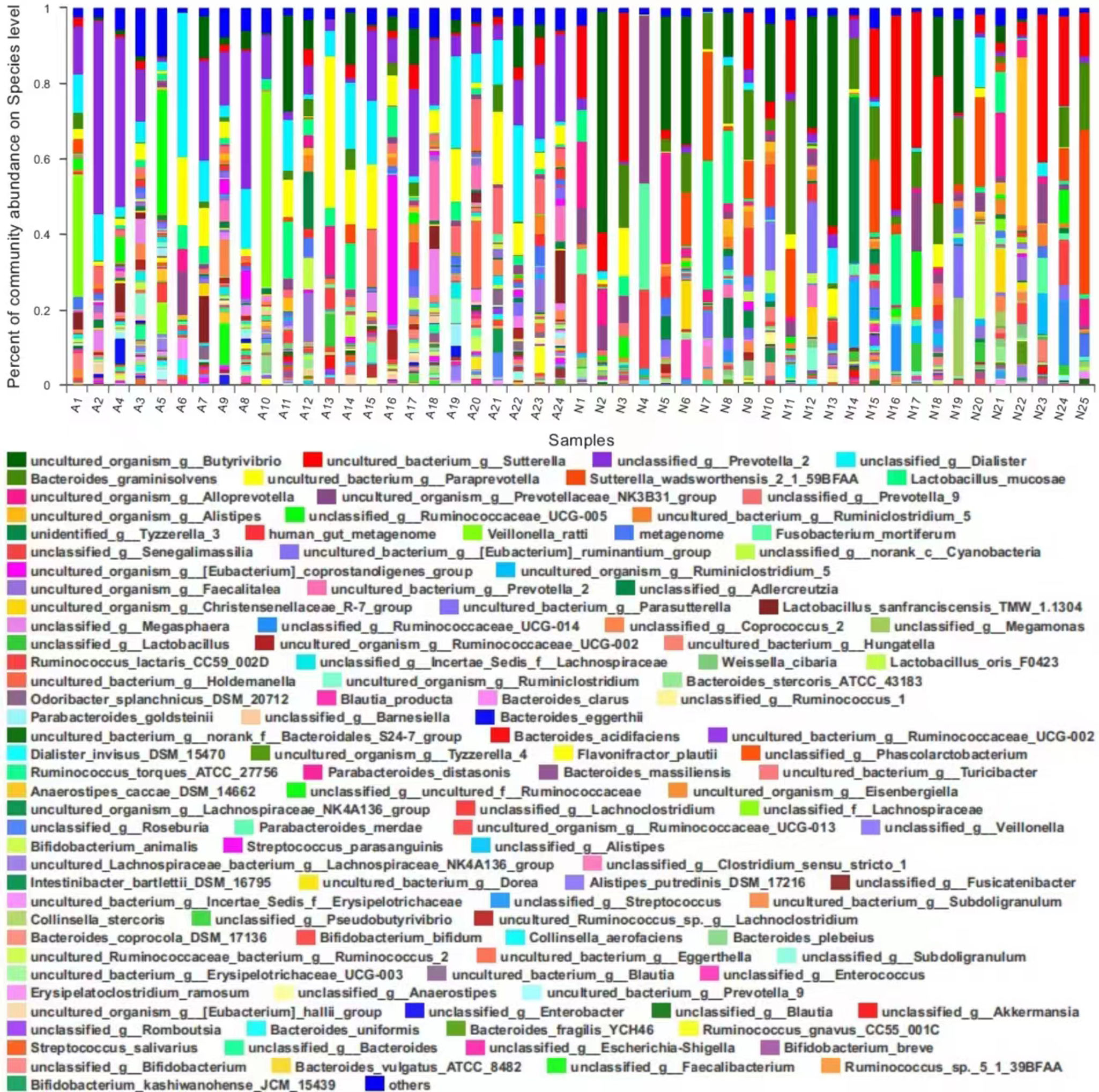

Analysis of community compositionThe bacterial taxa (i.e., community composition) and their abundance in each sample at the species level are shown in Figure 2.

Differential analysis of dominant bacteriaDifferences in the bacteria with abundance greater than 1% at different levels were analyzed between the two groups. Figure 3a shows that the abundance of Bacteroidetes in the anorexia group was higher than that in the control group, and the abundance of Actinobacteria in the control group was higher than that in the anorexia group at phylum level. Figure 3b shows the abundance of Bacteroidetes, Faecalibacterium, Subdoligranulum, Alistipes, Ruminococcus, Pseudobutyrivibrio, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, Parabacteroides in the anorexia group was higher than that in the control group, and the abundance of Bifidobacterium, Blautia, Lachnoclostridium, Streptococcus, Erysipelatoclostridium, Eggerthella in the control group was higher than that in the anorexia group at the genus level.

B/F index analysisThe ratios of the percentage abundance of Bacteroidetes to that of Firmicutes (the B/F index) in the two groups are depicted in Table 2, which shows that the B/F index in the anorexia group was higher than that in the normal group.

LEfSe multilevel species difference analysisIn this study, bacterial taxa with a default LDA score greater than 4.0 served as significant different bacterial taxa (biomarkers) between the two groups. At the phylum level, the significant influential bacterial taxa in the anorexia group were Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria (Fig. 4a) in the control group. At the genus level, Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium, and Subdoligranulum (Fig. 4a) were the significant influential bacterial taxa in the anorexia group and Bacteroides had the most influential effect (Fig. 4b), whereas in the control group Bifidobacterium, Blautia, Streptococcus, Lachnoclostridium, and Erysipelatoclostridium (Fig. 4a) were the significant influential taxa, and Bifidobacterium had the most influential effect (Fig. 4b).

DiscussionThe results of the α-diversity analysis indicate that the abundance and diversity of intestinal bacteria in the anorexia group were greater than those in the control group, that is, the α-diversity of the control group was lower than that in the anorexia group. Most studies have shown that increased diversity of the intestinal microbiota is beneficial to human health, whereas decreased diversity of the intestinal microbiota is mostly related to disease states, such as obesity, diabetes, allergic diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, and autism, as well as the use of antibiotics2,10,13,34. In general, greater richness of the microbiota corresponds to a better ecotype of the colony and a stronger ability to resist the invasion of foreign bacteria or other microorganisms. Therefore, the results of this study contradict traditional research conclusions. While Duan8 and Zhou40 found no difference in the α-diversity of the intestinal microbiota between infants with breast milk jaundice and infants without jaundice, Normann25 found that the α-diversity indexes of the intestinal microbiota did not differ between the necrotizing enterocolitis group and the control group. Furthermore, a 10-year follow-up study24 showed that in a high-risk female population, higher vaginal bacterial diversity was associated with an increased risk of HIV infection. These findings indicate that higher bacterial diversity is not necessarily better and that a change in intestinal bacterial α-diversity may not have significant positive correlations with the occurrence, development, and severity of disease. Furthermore, in this article, there were five significant bacterial species in the control group, while three significant bacterial species in the anorexia group at the genus level by the LEfSe multilevel species difference analysis in Figure 4. That is the control group has more dominant microbial communities than the anorexia group, which may suggest that the β-diversity analysis is more meaningful for bacterial communities with significant effects than for all the bacteria present in the gut which showed by α-diversity analysis.

The results of the analysis of taxa composition and the analysis of community composition indicate that the gut microbiota in the two groups included a variety of bacteria and were characterized by community diversity. High-throughput sequencing can be used to understand the gut microbiota composition comprehensively33.

The dominant bacterial phyla in the two groups were identical and included Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia, which is consistent with data in previous reports showing that 98% of the gut microbiota belong to four phyla, namely, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria7,21,39.

Turnbaugh and Ley16,32 confirmed that a decrease in Bacteroides or a decrease in the B/F index may promote obesity, and Lim18 found that the B/F index in the intestines of overweight patients was decreased. By contrast, Turnbaugh31 found that the genus Bacteroides, which is rich in genes encoding carbohydrate-metabolizing enzymes, was the main constituent of the intestinal microbiota in emaciated subjects. Research has shown3,23,29 that Firmicutes can help the human body absorb heat from food more effectively, then gradually convert food into fat and can regulate the expression of energy storage-related genes, while Bacteroidetes can effectively break down carbohydrates. Therefore, individuals with a high abundance of Bacteroides in their gut microbiota are less prone to gaining weight. The children included in the study were not obese and the abundance of Bacteroidetes in the anorexia group was higher than that in the control group, and the B/F index in the anorexia group was higher than that in the control group. These results may indicate that an increase in Bacteroides or in the B/F index can promote decreases in body weight.

Studies have shown that an early depletion of intestinal Bifidobacteria is associated with severe acute malnutrition. Kalliomaki's study showed that the proportion of intestinal Bifidobacteria in overweight children were lower than in normal-weight children of the same age. Bifidobacterium, a typical probiotic, can promote colon health by producing organic acids such as acetate and lactate and can inhibit pathogens. Anaerobes, especially Bifidobacteria, are the major protective organisms in the maturation of a healthy gut microbiota. Thus, an increase in Bacteroides abundance and a reduction in Bifidobacterium abundance may be related to the occurrence of anorexia. The effective rate of Bifidobacteria in the treatment of infantile anorexia is reported to be 77.5–93.2%. Therefore, for pediatric patients with anorexia, Bifidobacteria may be selected for treatment prior to the analysis of the intestinal microbiota9,12,14,36.

Furthermore, as the LEfSe multilevel species difference analysis showed in this study, the significant influential bacterial taxa in the anorexia group was Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria in the control group at the phylum level. Moreover, at the genus level, Bacteroides had the most influential effect in the anorexia group and Bifidobacteria in the control group. These findings support the fact that Bacteroidetes are involved in the onset of anorexia, and Bifidobacterium plays a major role in maintaining a normal intestinal microbiota17,22.

However, each individual has a unique gut microbiota1,38. In the control group, although the overall percentage of Bifidobacterium abundance (29.75%) was the highest, Bifidobacterium spp. were not necessarily the dominant bacteria that ranked first in every sample. For example, the most dominant bacterial genera were Lachnoclostridium in N4, Streptococcus in N21, and Blautia in N23. In addition, interactions occur among various dominant genera; in particular, when the abundance levels are similar [for example, the percentage of Bifidobacterium abundance (20.83%) was the same as that of Blautia abundance (20.83%) in N10, synergistic and restrictive interactions will be stronger, with the dominant genera jointly participating in the onset of disease or jointly maintaining the normal structure and function of the gut microbiota4,27. These interactions may explain why the conditions of some children with anorexia are not improved after treatment with Bifidobacteria as the most dominant bacteria may not be Bifidobacteria (or not solely Bifidobacteria) in these children but rather Bifidobacteria and other bacteria that together constitute the normal gut microbiota26,31,37. Therefore, supplementation with Bifidobacteria alone is not sufficient, and different probiotics must be selected based on the intestinal characteristics of each individual.

ConclusionThe increase in Bacteroides abundance or in the B/F index and the reduction in Bifidobacterium abundance were related to the pathogenesis of anorexia.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and they all declared that they have no competing interests.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the relevant ethics committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical College (2015 No. 01). Furthermore, prior to the study, a signed informed consent was obtained from the children's guardians.

FundingFund of Science and Technology Department of Guizhou Province (Basic of Qkh-ZK [2024] General 312), Joint Fund of Zunyi Science and Technology Bureau (ZSKHHZZ (2022) No. 363), Joint Fund of Zunyi Science and Technology Bureau (ZSKHHZZ (2020) No. 244), Joint Fund of Science and Technology Department of Guizhou Province (Qkhlhz [2015] No. 7518), Doctor Scientific Research Launch Fund of Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical College (Hospital (2014) No. 01).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.