Small-bowel atresias are among the most common causes of intestinal obstruction in newborns, and they often require urgent surgical treatment. Imaging techniques play a very important role in their diagnosis, which is often suspected on prenatal obstetric ultrasound and confirmed on postnatal plain-film X-rays. Abdominal ultrasound's lack of ionizing radiation, wide availability, low cost, and high resolution is making this technique increasingly important in confirming atresias and in detecting possible complications in newborns. This review analyzes a series of cases seen at our center. It summarizes the different types of small-bowel atresias, focusing on the clinical presentation, imaging findings on different modalities, presence of associated disease, management, clinical course, and outcomes.

Las atresias de intestino delgado son una de las causas más frecuentes de obstrucción intestinal en el neonato y habitualmente requieren tratamiento quirúrgico urgente. Las técnicas de imagen conforman una parte muy importante del diagnóstico, aportando la ecografía obstétrica prenatal la sospecha inicial y siendo la radiografía simple de abdomen la prueba que confirma el diagnóstico tras el nacimiento. La ecografía abdominal en el recién nacido está cobrando cada vez mayor importancia, debido a su inocuidad, disponibilidad, bajo coste y alta capacidad de resolución, tanto para la confirmación del diagnóstico como para la detección de las posibles complicaciones asociadas. En este artículo analizamos una serie de casos vistos en nuestro centro y elaboramos un resumen de los diferentes tipos de atresias de intestino delgado, haciendo hincapié en la clínica, los hallazgos radiológicos obtenidos en las diferentes modalidades de imagen, la existencia de patología asociada, su manejo y su evolución.

There are numerous birth defects that can affect the gastrointestinal tract, from the oesophagus or stomach to the small and large intestines. Assessment may require different imaging tests, both for diagnosis and for surgical planning. Radiologists therefore need to be familiar with the clinical presentation of these disorders so they can contribute by providing a precise and accurate diagnosis that helps determine the best possible surgical procedure.

Intestinal atresias are one of the most common causes of intestinal obstruction in newborns. The most common location is the jejunum, followed by the duodenum and the colon. In this review, we analyse the different types of small bowel atresia and the associated imaging findings. We also assess the utility of the different imaging modalities routinely used in the diagnosis of atresia, with plain X-rays and ultrasound being the most common in the paediatric population.

Pyloric atresiaPyloric atresia is a rare condition that affects one in 100,000 births and accounts for 1% of all gastrointestinal atresias.1 It is thought to be due to an error between weeks 5 and 12 of embryonic development, with a lack of recanalisation of the duodenum, and not to an ischaemic event.2

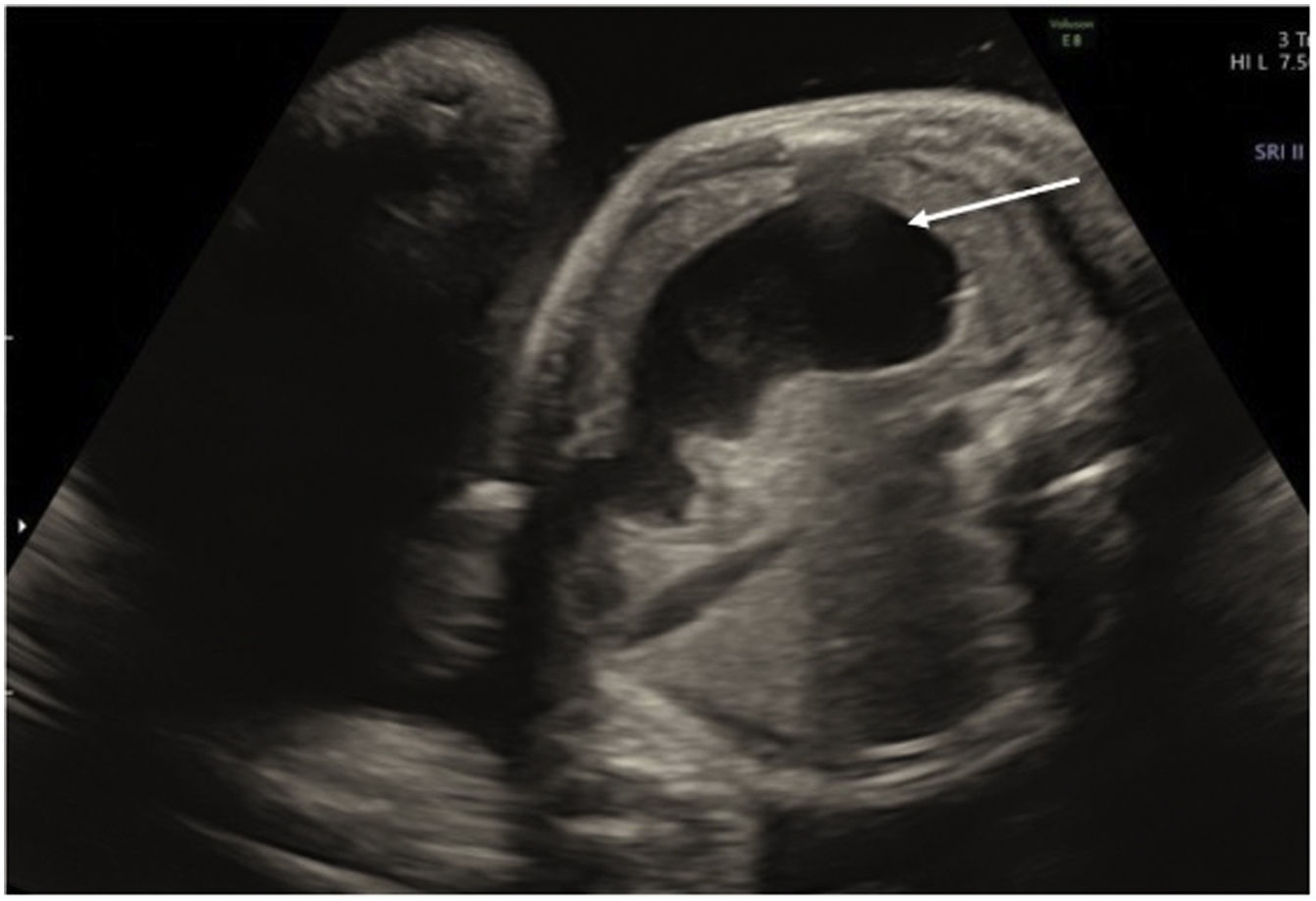

The case we present is of a newborn girl delivered at 38 weeks after a well-controlled pregnancy. Prenatal ultrasound revealed polyhydramnios and gastric chamber distension with fluid (Fig. 1), with little distal content. With these findings, gastric or duodenal atresia was suspected.

An emergency caesarian section was performed due to loss of foetal well-being, with immediate placement of a nasogastric tube.

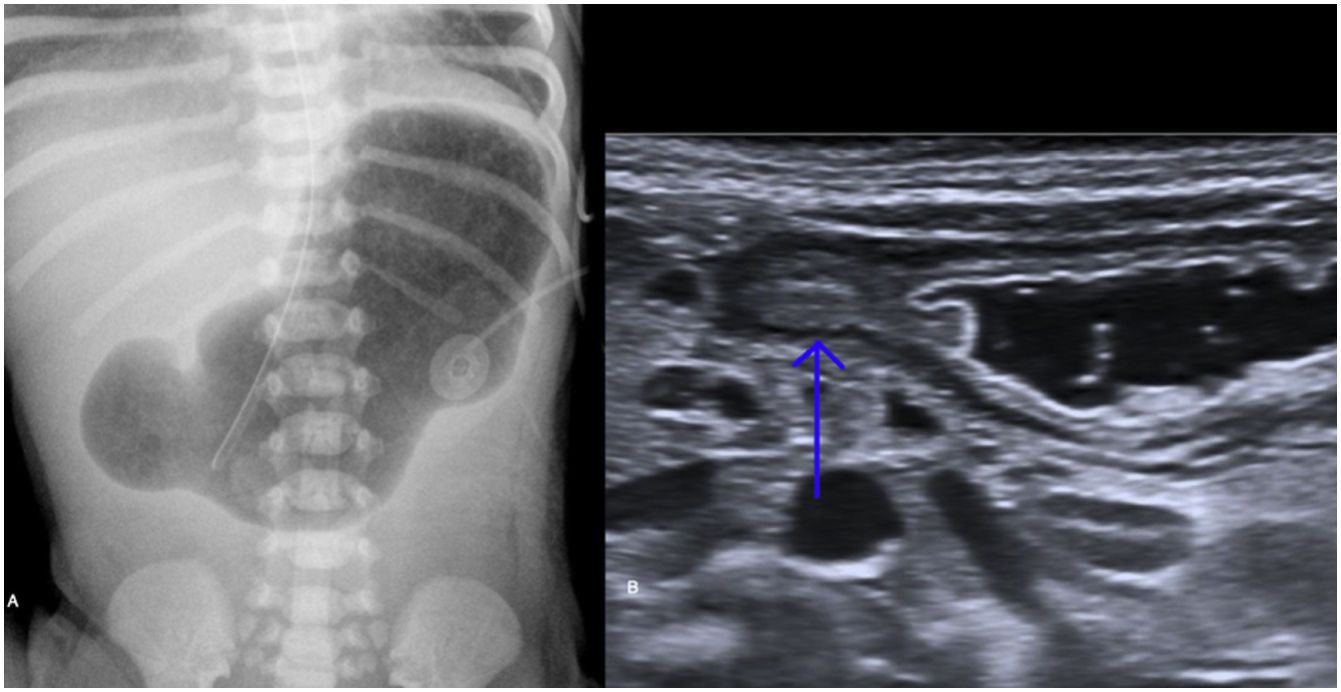

Plain abdominal X-ray (Fig. 2A) showed the distension of the gastric chamber and the absence of distal gas, known as the "single bubble sign". The presence of this sign made a diagnosis of gastric or pyloric atresia highly likely.3 An abdominal ultrasound was performed to identify any other concomitant abnormalities (Fig. 2B). The only relevant ultrasound finding was an enlarged pylorus with parietal thickening and absence of distal transit.

The most commonly used imaging technique for diagnosing this malformation has traditionally been plain X-ray, but ultrasound is becoming more important because it does not emit radiation and is also useful for identifying other possible abnormalities, with a sensitivity and specificity close to 100%.4

Three types of pyloric atresia have been described5:

Type A: caused by a diaphragm or pyloric membrane; as confirmed by pathology examination in our case (estimated frequency of 57%).

Type B: a fibrous tissue or cord that obstructs the pyloric lumen (33%).

Type C: where there is a space between the stomach and the duodenum (9%).

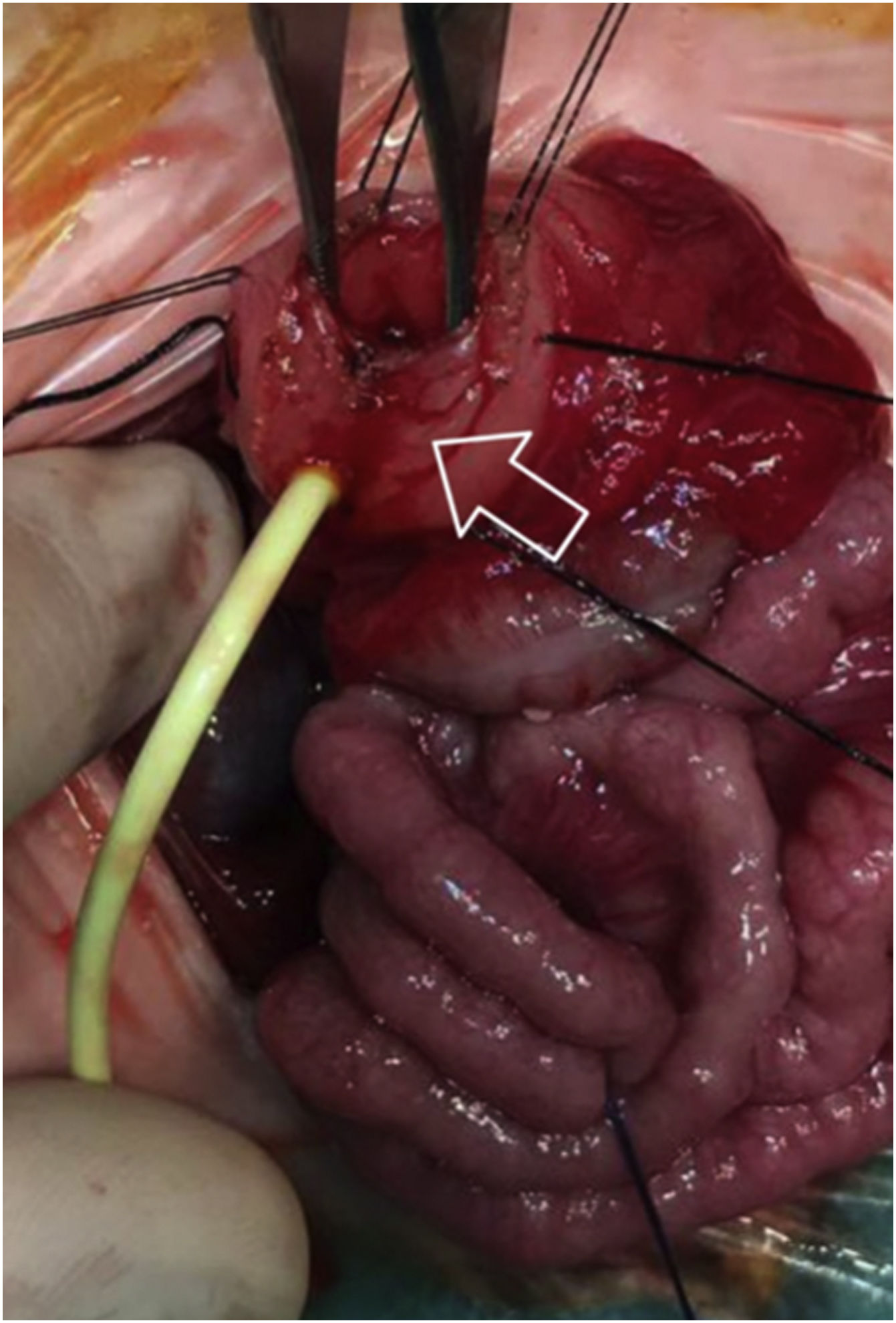

Twelve hours after delivery, an exploratory laparotomy confirmed type A pyloric atresia. The surgical repair technique used was a pyloroplasty with placement of a transpyloric tube (Fig. 3).

The patient made a good recovery, without any postoperative incidents and with progressive enteral feeding. Transfontanellar ultrasound and follow-up abdominal X-ray were normal and the patient was discharged at 17 days of life.

Although this malformation can occur in isolation, it is often accompanied by other cardiac, genitourinary or intestinal abnormalities.5 There is a known association with epidermolysis bullosa letalis ("Carmi syndrome"), a serious disorder with high morbidity and mortality rates.2

The classic sign is of a newborn with non-bilious vomiting, especially after feeding. During the pregnancy, it is common to find maternal polyhydramnios, caused by the inability of the foetus to digest the amniotic fluid. On prenatal ultrasound, there is distension of the gastric chamber with no signs of material in the distal intestine.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of gastric obstruction in the newborn, such as hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, pyloric duplication, gastric volvulus, ectopic pancreatic tissue, double pylorus and gastroduodenal intussusception.6 With the difficulty in discerning between the different causes of pyloric obstruction on plain X-rays, ultrasound studies are taking on an increasingly important role, as the passage of content through the pylorus can be visualised in real time and extrinsic causes of compression identified. Ultrasound can also help detect associated abnormalities in different cases of atresia.7 In contrast, barium studies are contraindicated due to the risk of gastroesophageal reflux or bronchial aspiration pneumonia. Computed tomography (CT) is also contraindicated because of the high dose of radiation, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not often performed due to limited availability and the need to sedate the patient.

Early surgical treatment is the "gold standard" and, in the absence of other associated malformations, it has a good prognosis and few complications.1,2

Duodenal atresiaDuodenal atresia is the most common cause of upper intestinal obstruction in newborns8 and affects one in every 6,000-10,000 births, with no predisposition related to either gender or ethnicity.9 It is normally caused by an error in the recanalisation of the duodenum between weeks 8 and 10 of embryonic development.9

In our second case, our patient was a newborn male delivered by caesarean section after 36+6 weeks of a well-controlled twin pregnancy. In the prenatal ultrasound at 24 weeks, polyhydramnios and dilation of the gastric and duodenal chambers were identified in one of the foetuses. These findings strongly suggested the existence of duodenal atresia. In both foetuses, echocardiogram and genetic analysis were normal.

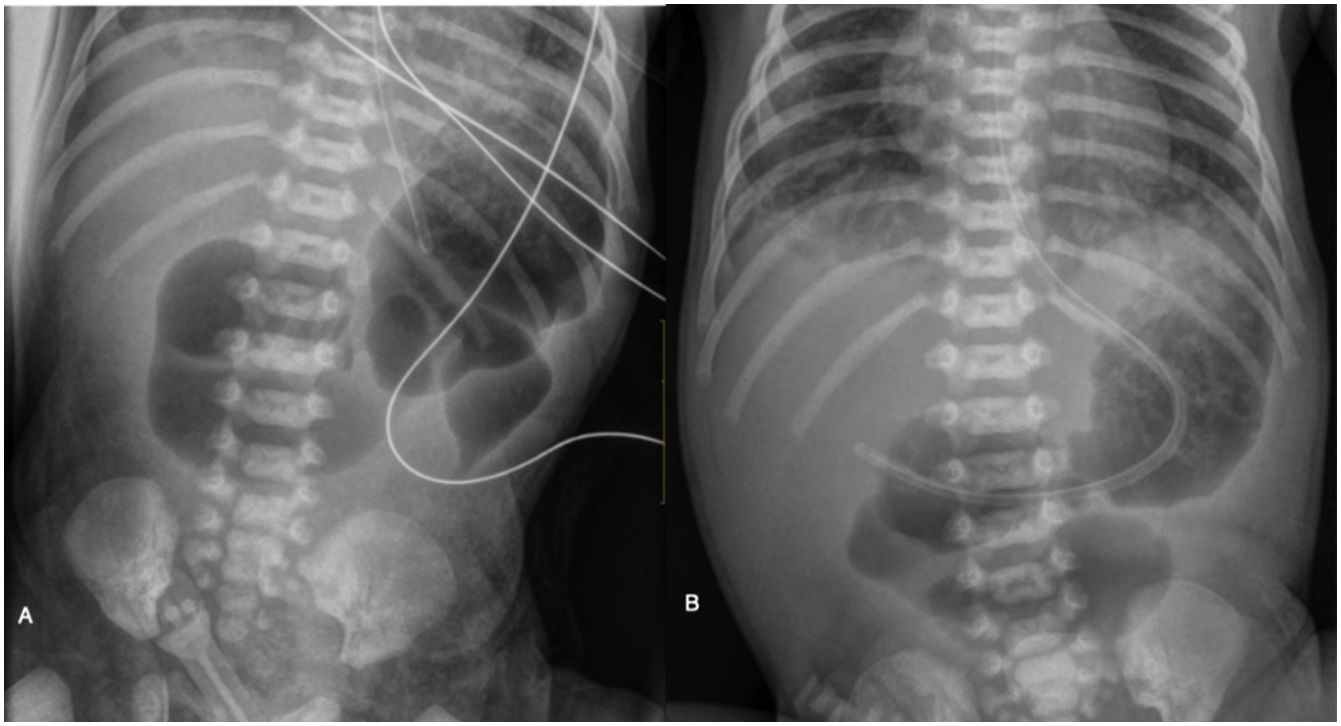

Immediately after delivery, X-ray of the chest and abdomen (Fig. 4A) detected air in the gastric chamber and in the duodenum, but not more distally; this finding is known as the "double bubble sign".8,10 An abdominal ultrasound was also performed (Fig. 4B), showing the same abnormalities.

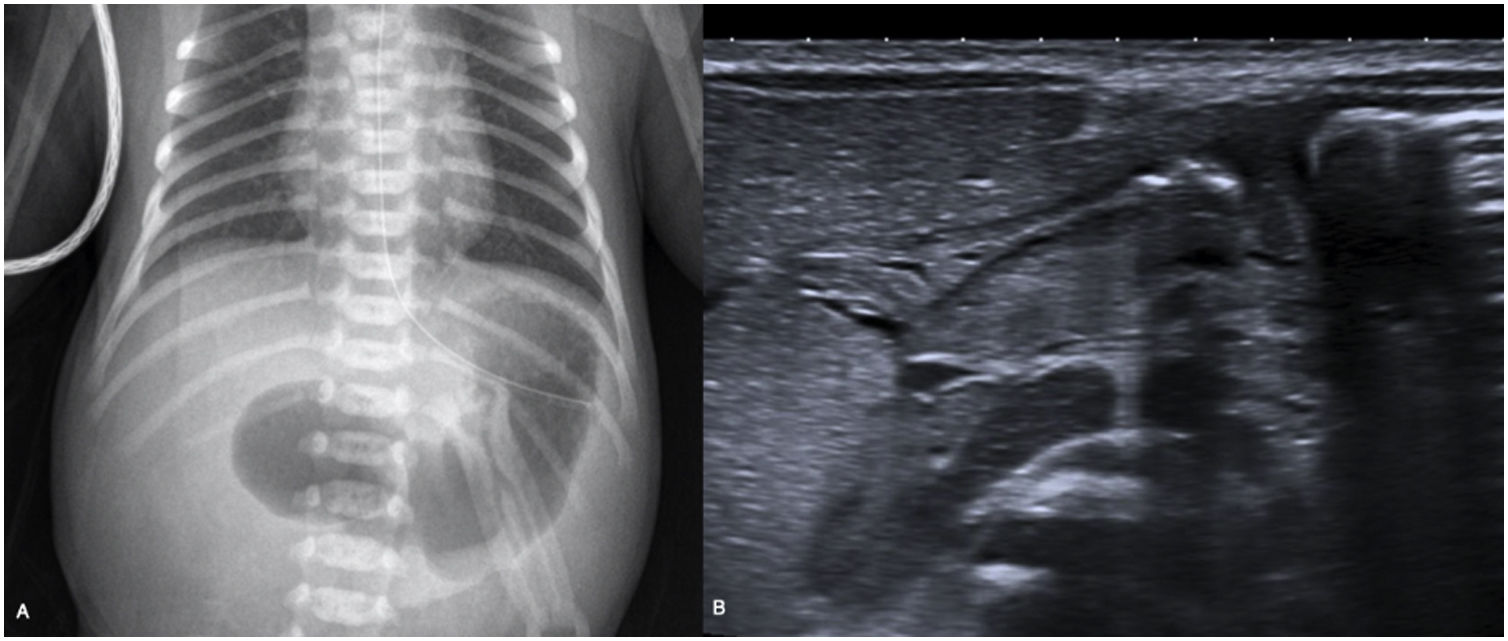

A few hours after birth, an urgent duodeno-duodenostomy was performed, confirming complete occlusion of the duodenum accompanied by annular pancreas and intestinal malrotation. After surgery, repeat X-ray of the chest and abdomen showed an adequate intestinal air luminogram (Fig. 5). The patient made good progress with gradually increasing enteral nutrition and was discharged at 13 days old.

Although the diagnosis of duodenal atresia can be established by plain X-ray, ultrasound has the advantage of distinguishing between atresia and stenosis by showing the passage of content through the duodenum, as well as identifying potential causes of extrinsic compression. If incomplete duodenal obstruction is suspected, a gastrointestinal transit study is indicated.

As we found in the surgical intervention on our patient, annular pancreas is a congenital malformation caused by the incomplete migration of the ventral region of the pancreas, which ends up surrounding the second part of the duodenum9 and can coincide with duodenal stenosis or atresia.11 This is the congenital malformation most commonly linked to duodenal atresia.9

Two types of annular pancreas have been described9,10:

- 1

Extramural: in which the ventral pancreatic duct surrounds the duodenum to join the main pancreatic duct, causing a mechanical intestinal obstruction.

- 2

Intramural: in this category, the pancreatic glandular tissue intermingles with the muscle fibres of the duodenal wall, causing duodenal ulceration.

The extramural variant can be associated with Down's syndrome (20-30%), intestinal malrotation (20%), oesophageal atresia (10-20%) and congenital heart malformations (10-15%).8 This disorder can cause obstructive symptoms in the newborn of varying severity depending on the degree of obstruction caused by the annular pancreas itself and whether or not there is duodenal stenosis or atresia.11

Although the diagnosis of duodenal obstruction is simple with prenatal ultrasound, annular pancreas is more complex to detect and it may not be identified until surgery.11 The diagnosis in older children and adults can be obtained with barium studies, CT or MRI.

The treatment of duodenal atresia with annular pancreas is surgical correction through a duodeno-duodenostomy above the pancreas, placing two tubes, one transanastomotic for feeding and the other gastric for bile reabsorption.9 If there are no other malformations, essentially cardiac or Down's syndrome, this disorder has a very good prognosis.9 The main late surgical complications are blind loop syndrome, dysmotility, megaduodenum, gastritis, oesophagitis, gastroesophageal reflux, peptic ulcer, pancreatitis and cholecystitis.9

Jejunal atresiaJejunal or jejunoileal atresias differ from those located proximally in their aetiology, associated abnormalities, treatment and even prognosis.12 They are more common than duodenal atresias and are caused by an ischaemic event during pregnancy, which can be caused by intussusception, perforation, volvulus, hernia or thromboembolism. The estimated incidence is 1-3 per 10,000 births. There is no gender predisposition and it is uncommon for it to be accompanied by other malformations.12 We present two cases as examples of this condition.

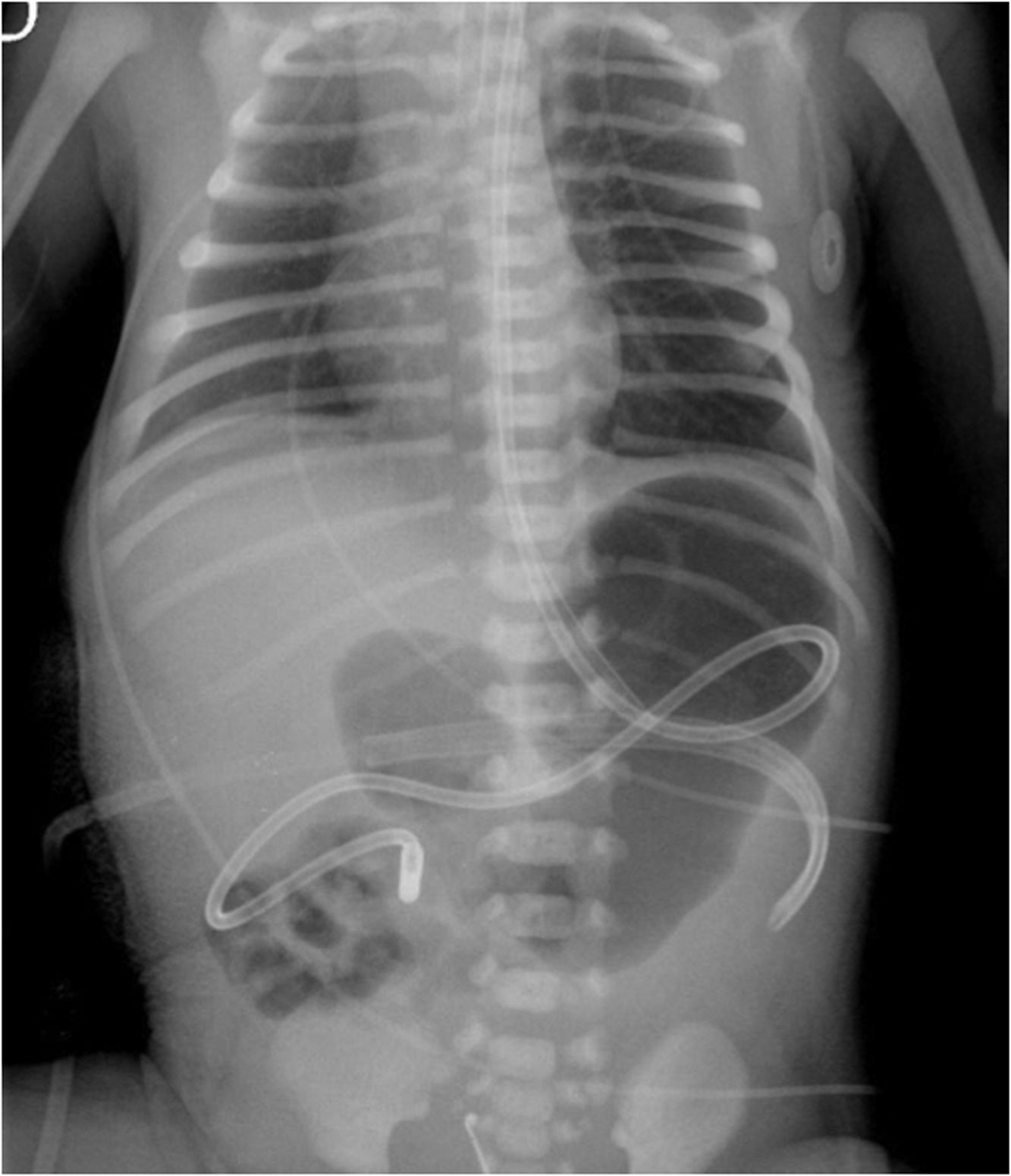

The first case is that of a newborn male delivered by emergency caesarean section due to loss of foetal well-being. In the prenatal studies, there was a slight dilation of the small intestine, as well as polyhydramnios. Abdominal X-ray was performed just after birth (Fig. 6), in which a "stop" was found in the midgut.

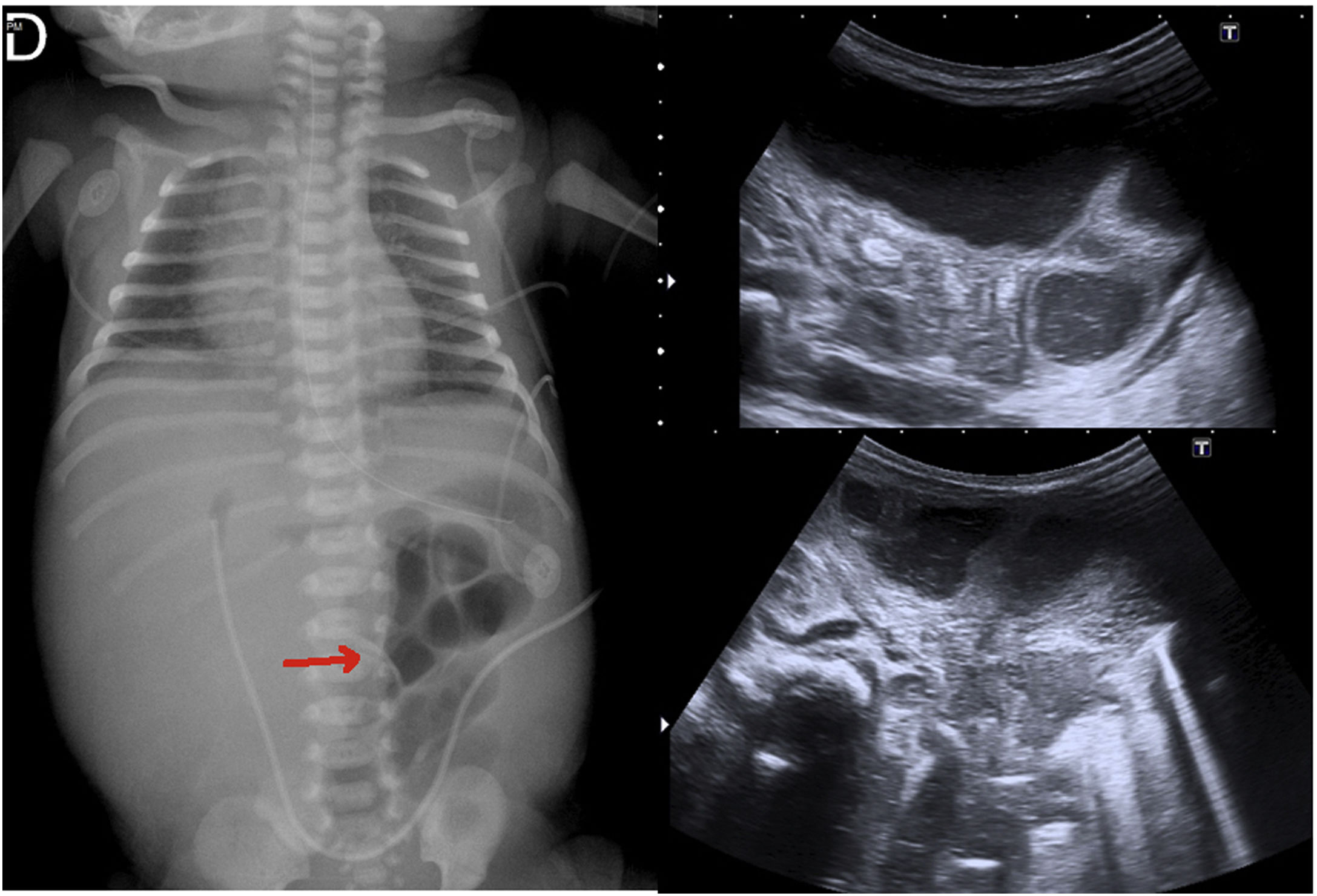

The second case was a newborn delivered by caesarean section at week 36 + 3 after a well-controlled and tolerated pregnancy. Dilation of the intestinal loops had been identified in the obstetric ultrasound at week 33, consistent with meconium ileus or ileal atresia. Our patient had bilious vomiting after birth. The X-ray taken just after delivery (Fig. 7A) showed absence of distal gas with distended segments on the left flank. An abdominal ultrasound was also performed, which showed a small amount of free fluid surrounding the bowel loops (Fig. 7B and 7C).

Both intestinal atresia and meconium ileus are characterised by dilation of numerous small bowel loops with no distal gas. However, they differ in that air-fluid levels are common in atresia, while in ileus a characteristic finding is a relative lack of air-fluid levels, as the loops are full of meconium.13

The main advantage of ultrasound is that, in addition to identifying the dilation of the intestinal lumen, it also allows us to assess the thickness and vascularisation of the wall and any free intra-abdominal fluid. When the diagnosis requires distinguishing between ileal atresia and meconium ileus, the presence of echogenic contents, with or without gas, is highly suggestive of meconium ileus.14 One disadvantage of ultrasound compared to plain X-ray studies is the greater difficulty in determining the exact site of the obstruction.15 The two techniques can be combined for a better preoperative assessment. In this second patient, all the findings taken together, both radiographic and ultrasound, pointed us in the direction of ileal atresia.

As in our cases, when intestinal atresia or ileus is suspected, it is essential to identify patterns that suggest the presence of meconium peritonitis due to intrauterine intestinal perforation, as this can alter the prognosis and treatment.16 The classic findings on plain X-ray are calcifications outlining the intra-abdominal structures and partially calcified masses. In these cases, ultrasound plays an important role in identifying intra-abdominal cystic lesions, with or without calcifications and ascites.17

Additionally, in the case of jejunal atresia, with distension of the proximal intestine on plain X-ray and absence of distal gas, a gastrointestinal transit test may be justified; as the cause is ischaemic, the coexistence of multiple atretic segments is not uncommon. However, if there are multiple distended loops with gas, the obstruction is presumed to be distal, ileal or colonic, so the test indicated is a barium enema.18 In these cases, in addition to indicating the exact point of obstruction, in the case of meconium ileus the enema would be both diagnostic, identifying filling defects, and therapeutic.19

In the first patient, with abdominal X-ray as the only imaging test, we opted straight away to perform an exploratory laparotomy, where type 1 jejunal atresia was diagnosed.

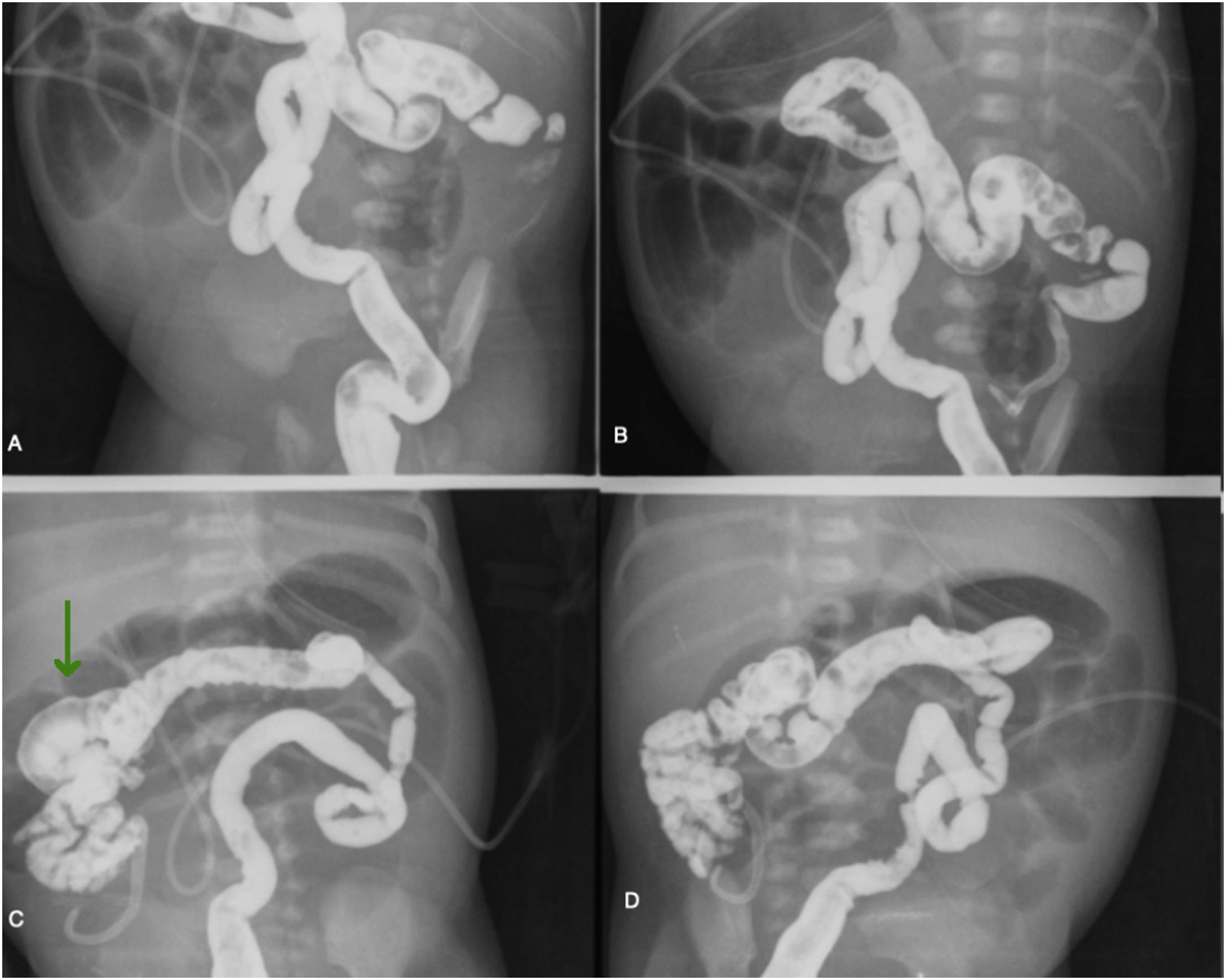

In the second case, as ileal atresia was suspected, in order to help with surgical planning a barium enema was performed to assess both the exact point of the atresia and the distal segment, where there might have been further stenosis.4

In this patient, we used 50 ml of nonionic iso-osmolar contrast [Iohexol (INN), OMNIPAQUE® 300] diluted in 25 ml of normal saline, to minimise any complications from the use of hyperosmolar contrast (dehydration, perforation, etc.)19 and due to the small likelihood of it being meconium ileus (Fig. 8). The images show a colon with decreased lumen, probably resulting from lack of use. The contrast seems to reach the distal ileum, with no evidence of connection to the proximal small intestine.

Both the surgery (Fig. 9) and the pathology report confirmed jejunal atresia, probably caused by an intrauterine ischaemic insult.20

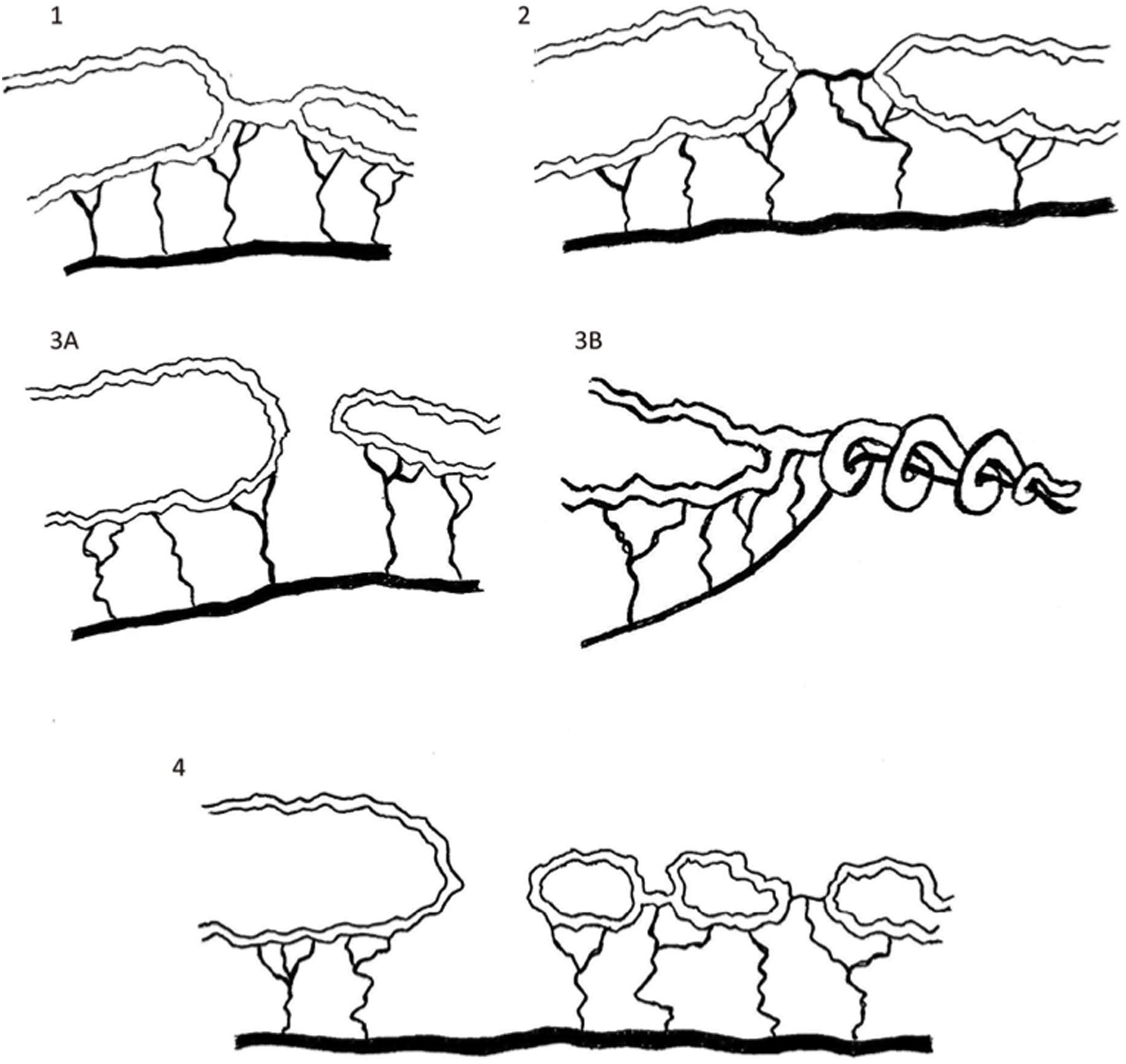

There is a classification system for the different types of jejunal atresia according to their characteristics and which part of the jejunum they are located in (Fig. 10):

Diagrams of the types of jejunal atresia inspired by "Intestinal atresia". Source: Coppola et al.12

Type I: occlusion of the lumen with the bowel wall and mesentery intact.

Type II: the two atretic ends are connected by fibrous tissue without mesentery involvement.

Type IIIA: the atretic ends are blind, separated by a V-shaped discontinuity of the mesentery.

Type IIIB: the atresia is located near the ligament of Treitz with a short proximal bowel and a discontinuity of the mesentery ending in a cul-de-sac. The distal small intestine rolls over the mesentery, causing a "Christmas tree" or "apple peel" deformity.

Type IV: there are multiple atresias at different levels.

According to the literature references consulted, the prognosis of jejunal atresia is excellent, with survival as high as 90%, although it deteriorates in patients who require resection of bowel segments.

In both of our cases, the babies remained asymptomatic after surgery, with no postoperative complications, and neither of them have required any further admissions to hospital since then.

ConclusionThe diagnosis of an abnormality in the gastrointestinal tract in newborns depends predominantly on clinical findings, although the role of imaging tests, particularly ultrasound, is gaining importance. In addition to the initial diagnosis, radiology helps determine as exactly as possible the nature of the abnormality and so contributes to surgical planning. This aim of this review was to provide different clinical examples to demonstrate how the different imaging modalities can help in the diagnosis of intestinal atresia in the newborn.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for the integrity of the study: AMD and MCM.

- 2

Study conception: FCC.

- 3

Study design: AMD and MCM.

- 4

Data collection:

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation:

- 6

Statistical processing:

- 7

Literature search: MCM.

- 8

Drafting of the article: AMD and MCM.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: AMD, MCM and FCC.

- 10

Approval of the final version: AMD, MCM and FCC.

None. This study received no specific grants from public agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Our thanks to Dr Nuria Valiño Casal, gynaecologist and expert in prenatal ultrasound, for allowing us access to her images, and to Dr Isabel Casal Beloy, paediatric surgeon in charge of the patients. We would also like to thank the patients' parents, who gave their oral consent for the writing of this article.

Please cite this article as: Maestro Durán MA, Costas Mora M, Camino Caballero F. Atresias de intestino delgado. Revisión de la patología y hallazgos radiológicos asociados a distintos casos. Radiología. 2022;64:156–163.