Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in Peruvian women. Due to limitations in national breast cancer screening programs, especially in rural areas, more than 50% of cases of breast cancer in Peru are diagnosed in advanced stages. In collaboration with a local clinic registered as a nongovernmental organization (CerviCusco), RAD-AID International aims to create a sustainable diagnostic structure to improve breast cancer screening in Cuzco. With the support of local, national, and international partners that have collaborated in analyzing radiological resources, raising awareness in the population, acquiring equipment, training clinical staff, and building referral networks, our teams of radiologists, included in the RAD-AID team, have participated in training CerviCusco staff in breast ultrasound, thus enabling additional training for radiology residents through a regulated international collaboration.

El cáncer de mama es el segundo cáncer más frecuente en las mujeres peruanas. Las limitaciones de los programas nacionales de detección precoz, sobre todo en las regiones rurales, propician que más del 50% de los nuevos casos de cáncer de mama en Perú se diagnostiquen en estadios avanzados. RAD-AID Internacional, en colaboración con una clínica local registrada como organización no gubernamental (CerviCusco), pretende crear una estructura diagnóstica sostenible que mejore el cribado del cáncer de mama en Cuzco. Para ello se ha contado con socios locales, nacionales e internacionales que han colaborado en el análisis de recursos radiológicos, la concienciación de la población, la adquisición de equipamiento, el entrenamiento clínico y las redes de referencia. Nuestros equipos de radiólogos, incluidos en el equipo RAD-AID, han participado en la capacitación ecográfica del personal de CerviCusco, permitiendo una formación adicional a los residentes de radiología gracias a una colaboración internacional reglada.

Of the 31 million inhabitants of Peru, 1.2 million live in the Cuzco region,1 of which 20% live below the poverty line,2 a figure that probably reaches 50% in rural areas.3,4 The country’s development has improved basic health indicators, but the incidence of diseases such as cancer has also increased.4–6 Cancer has a high mortality rate, as in other countries with a similar level of development, primarily due to late diagnosis.7,8

Breast cancer is the second most frequent cancer in Peruvians (16%), only behind cervical cancer (24%), and is the second cause of hospital admission for cancer.9,10 But the figures may be even higher due to the lack of diagnostic resources in some regions,4,11 and the prevalence is expected to grow and cause more premature deaths if the limitations of the early detection programmes persist.9,12,13 Despite this, Peru is one of the few Latin American countries with a national plan for cancer care (Plan Nacional para la Atención Integral del Cáncer, formerly known as the Plan Esperanza [Hope Plan]), launched in 2012 by the Ministry of Health (MINSA).14–16 The plan offers patients with few resources universal coverage to detect and treat breast cancer through the Seguro Integral de Salud (SIS) [Comprehensive Health Insurance system]17 In addition, the Seguro Social de Salud (EsSalud) [Social Health Insurance] is another public network with its own facilities that covers the diagnosis and treatment of cancer for workers. Unfortunately, access to care is especially difficult in rural areas,5 more than 50% of new cases of breast cancer continue to be diagnosed in stages III and IV,18,19 and it is necessary to dedicate more efforts, especially in the most disadvantaged areas.

The Radiology Service of the Hospital General Universitario Morales Meseguer [Morales Meseguer General University Hospital] (SERAMME) recently participated with RAD-AID International in a programme to improve early detection of breast cancer in the Cuzco area.20 At the beginning of 2020, only two mammography units, dependent on EsSalud and the Regional Hospital, were operating in Cuzco, which means that, in order to comply with the national recommendation to carry out a screening study in women aged 50–69 years every three years, each unit should serve 60,000 women.9 For this reason, as in the rest of the country, access to screening outside the main cities continues to depend on private centres,9,21,22 where the cost of screening is prohibitive for the population covered by the SIS.22,29 According to some Peruvian studies, less than 20% of women over 40 years of age have a mammogram throughout their lives, when the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that, to have an impact, at least 70% of the target population should be screened.23,24

In the autumn of 2019, a new public centre opened in Cuzco, the Centro Oncológico Regional (COR) [Regional Oncology Centre], which has prevented patients from the region from necessarily having to travel to Lima to be treated, and makes it even more important to have infrastructure and training in breast imaging. But the lack of mammography units and trained personnel makes it necessary to look for alternatives to offer quick care while this rural area of Peru lacks these facilities. One of them is the clinical examination and guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB).9,12,21,25,26 It is known that clinical examination allows the disease to be detected earlier,24 which was demonstrated by a collaborative programme in northern Peru, which reduced FNABs by more than half, focusing on promoting breast health, clinical examination and ultrasound triage.18,25,27,28 Therefore, although ultrasound cannot replace mammography, integrating it into the breast cancer screening algorithm in this way can help in settings such as Cuzco.19

The RAD-AID International project aims to create a sustainable diagnostic structure that will make it possible to reduce the stage of breast cancer at the time of diagnosis in Cuzco and facilitate early treatment. The primary objective of this article is to explain the characteristics of the programme, the preliminary steps based on the analysis of needs and partners, the work on the ground, and the first results and future plans. The secondary objective is to highlight the volunteer experience based on a radiology service, beyond the individual initiatives of its members.

Preliminary steps: needs and partners1. Local scope. CerviCusco is a local clinic registered in Peru as a non-governmental organisation, committed to improving the health of economically disadvantaged Peruvian women or those with poor health access. It began its activity in 2008 thanks to an American initiative and covers an estimated population of one million people. It provides training and clinical health services focused on the primary and secondary prevention of cervical cancer, including prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment of precancerous lesions.30–32 In addition, it carries out mobile campaigns throughout the region to train and screen women who cannot travel to the clinic. It has a cytopathology laboratory with remote diagnosis from the USA by telemedicine, and refers cases with more advanced disease to regional and national cancer centres.20 But CerviCusco also perceived the need to care for patients with breast cancer, and given the coverage limitations of the national cancer screening programmes, it partnered with RAD-AID to set up a breast cancer detection programme based on clinical examination, ultrasound and biopsy while mammography screening was not available.

In accordance with the RAD-AID strategy, infrastructures and resources were first assessed8,13,20,33 and then strategic partners inside and outside Peru were identified to guarantee a sustainable programme.16,20,25,34–38 Combining cervical and breast cancer screening in rural Latin American communities has been successful in overcoming health barriers and has been well received by the population.20,38,39 In Cuzco, although CerviCusco did not have radiologists or a programme for detecting breast cancer, it was well placed to serve and educate the population, coordinate, acquire initial training from which to grow, and be able to offer referral services.

RAD-AID identified in CerviCusco a need for training (in clinical examination and ultrasound), equipment (ultrasound with linear transducer, cloud storage, mammography) and referral services. In addition, RAD-AID strengthened its alliance with the COR to take charge of the biopsies, surgical interventions and chemotherapy of patients referred from CerviCusco.

2. National scope RAD-AID made contact with essential partners in Peru, especially the Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplásicas (INEN) [National Institute of Neoplastic Diseases]. The institute is in charge of surveillance, planning and support, as well as the treatment of cases that cannot be handled at the COR. At the meeting, the INEN wanted to provide telemedicine support and training to local partners interested in doing ultrasound-guided breast biopsies. To support CerviCusco in accessing the local population, the Club de la Mama [Breast Club], a non-profit organisation affiliated to the INEN, assists with awareness campaigns focused on the circulation of patients, training, survival and advice. As the RAD-AID programme in Peru progresses, the partnership with the INEN will probably be more important to increase cancer detection, treatment and research in Peru.

3. International scope Its mission lies in the provision of human and material resources. SonoSite (Fujifilm) agreed to pay for a SonoSite Edge II portable ultrasound machine for RAD-AID; CerviCusco, with probes for breast, obstetric-gynaecological and abdominal studies,40 and Bard Medical donated biopsy material.

In addition, the programme needed to develop an information technology infrastructure. Ambra Health, an imaging and medical data management software company, and Google Cloud support the RAD-AID Friendship Cloud, a cloud-based picture archiving and communication system (PACS).41,42 Koios Medical donated decision support software to help interpret breast ultrasound using artificial intelligence.43 In addition, the Fred Hutchinson Center for Cancer Research (Seattle, WA, USA) helped create secure web tools for research electronic data capture (REDCap).44

Finally, SERAMME pledged to send two teams of radiologists annually, including right at the start of the programme, to provide training and technical and clinical support. The advantage of the shared language gives more relevance to the role of SERAMME in the relations of the CerviCusco staff with the RAD-AID project.

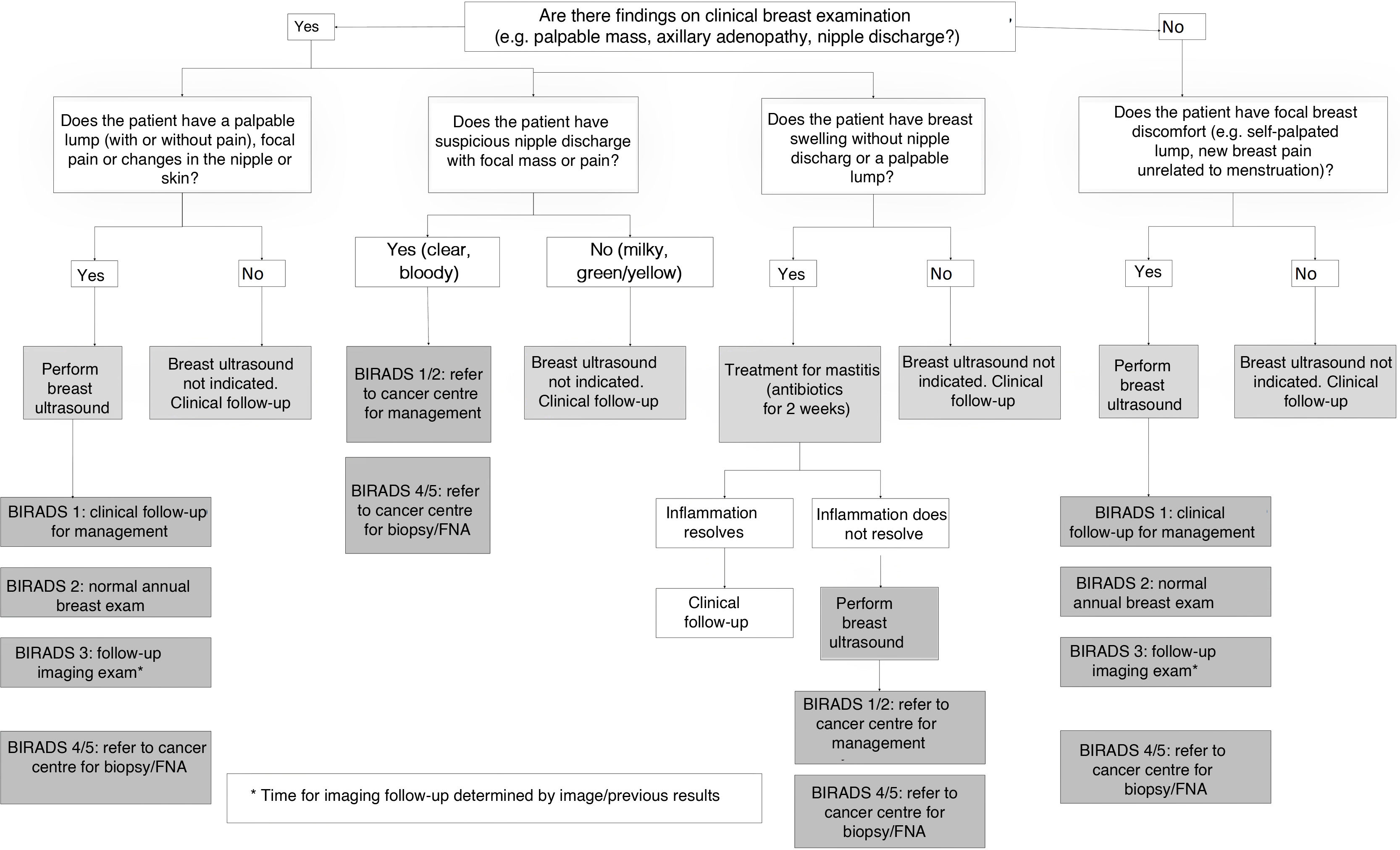

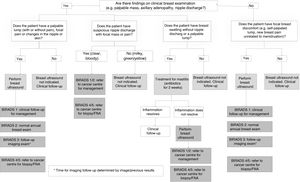

RAD-AID’s mission in Peru: start-upBreast cancer detection strategy in the Cuzco regionThe National Plan launched a breast cancer detection programme for 2017–2021,4,9,12,29 but it has not yet been effective, with less than 1% of cases diagnosed thanks to a screening or early detection programme.10,19 Although there are no randomised clinical trials that have evaluated the efficacy of clinical examination in the early diagnosis of breast cancer, combining it with ultrasound to detect it in earlier stages is a cost-effective strategy in settings with limited resources.37,45–48 RAD-AID and its local partners prioritised the effective detection and management of palpable cancer with exploration and ultrasound before investing in mammographic screening.20,21,28 This strategy follows the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) resource-stratified guidelines, which recommend using breast ultrasound in low-resource settings.12,13,24,26,49–51 According to them, the Cuzco region has “basic resources” (ultrasound and core needle biopsy (CNB) without screening or diagnostic mammography).50 The guidelines focus on clinical examination and medical advice to reduce risk, studying symptomatic cases with BI-RADS ultrasound. Applying them in low-income countries implies having: a) dissemination and implementation strategies (e.g. analysis of the radiological situation — Radiology Readiness Assessment), b) public training and information programmes, and c) technological possibility to detect, diagnose and treat the disease effectively.12,50 In accordance with this, RAD-AID Peru developed an algorithm to manage patients with a positive examination and ultrasound, with the collaboration of local, regional and national partners20,37 (Fig. 1). According to the objective of the project, the priority was to reduce the time between the onset of the disease and the diagnosis, and to detect and treat cancer in lower stages through clinical screening and ultrasound triage.

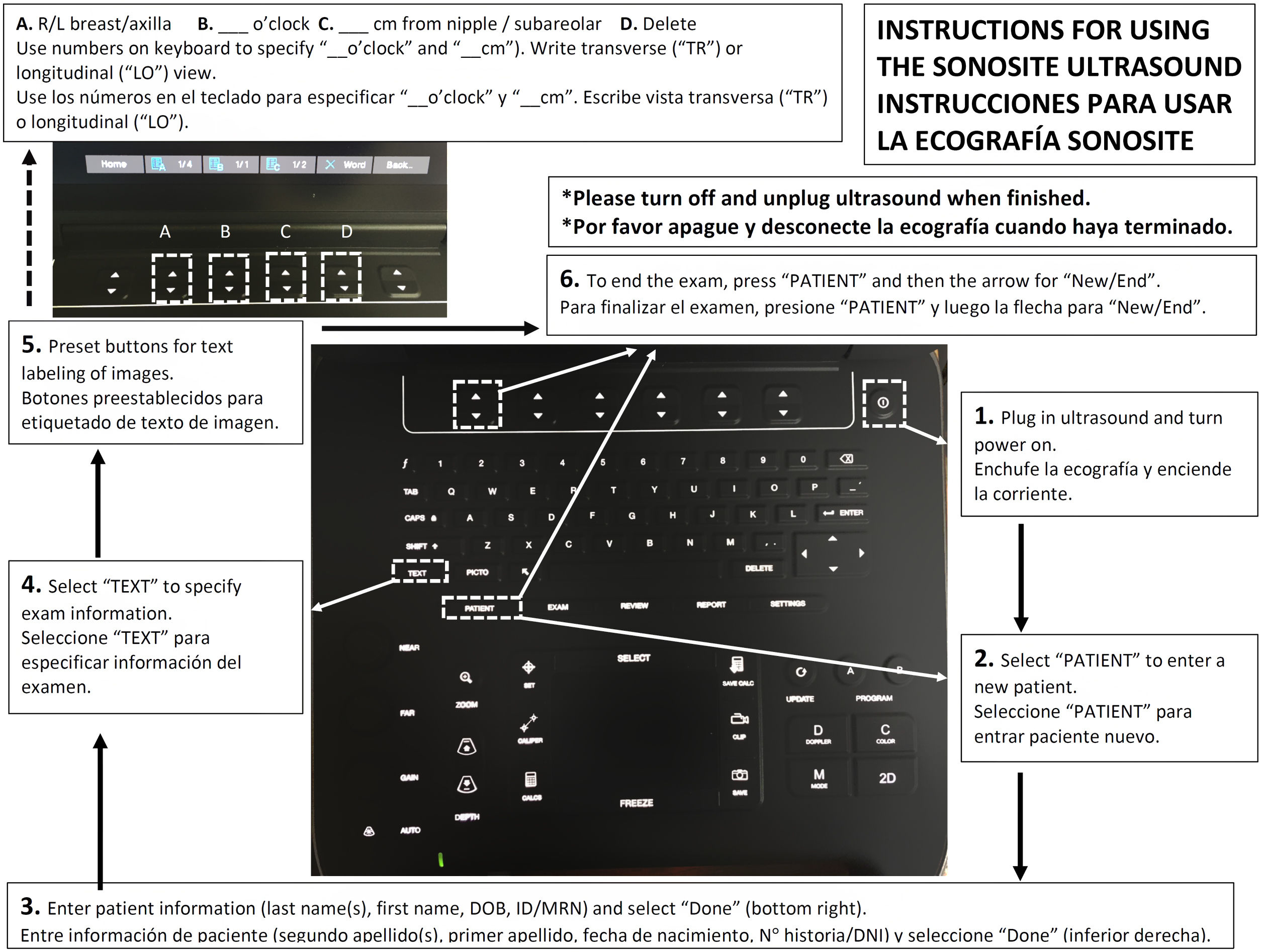

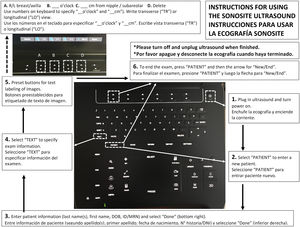

Launch of the programmeAfter the initial visit to Cuzco, RAD-AID Peru secured a portable ultrasound machine with a linear transducer and cloud storage software to install in a specific room in CerviCusco. Launching the pilot of the programme required coordination between RAD-AID, CerviCusco and the volunteers to start with face-to-face training of seven weeks supervised by certified radiologists. The volunteers, who were recruited through personal contacts or a RAD-AID announcement, were interviewed. The first team, made up of the director of the RAD-AID Peru programme, the coordinator of the RAD-AID promotion programme and a fourth-year medical student, assembled the equipment, began the training programme for local professionals and developed the protocols for the patient files, the use of the ultrasound system (Fig. 2) and referrals to referral centres.

Example of the support material for using the ultrasound system that RAD-AID developed and that served both CerviCusco staff and volunteer collaborators. The instructions illustrate how to enter the data for each patient prior to the study. Similar schemes existed for the basic functions of the ultrasound system (focus, depth, image capture, measurements, etc.).

The existing networks in CerviCusco were used to recruit patients through educational campaigns, both in Cuzco and in the nearby Andes, which focused on increasing the perception of breast health, highlighting annual screenings with clinical examination, and providing material adapted to local cultural characteristics.12,13,19,29,45,52 This campaign started two weeks before the launch of the programme and continued during the launch phase. To help achieve the goal of educating patients and screening, eight hours of talks from the Bettercare series Breast Care were translated into Spanish, and the Club de la Mama and National Plan initiatives were included.18,53–55 A local clinical curriculum previously validated in northern Peru and Uganda was collaboratively developed.28,48 For example, training in the use and interpretation of breast ultrasound and ultrasound-guided biopsy was provided to non-radiologist professionals.45,56 A standardised BI-RADS based on the previous success of international collaborations in other low-resource regions56–58 was used for ultrasound interpretation and management.

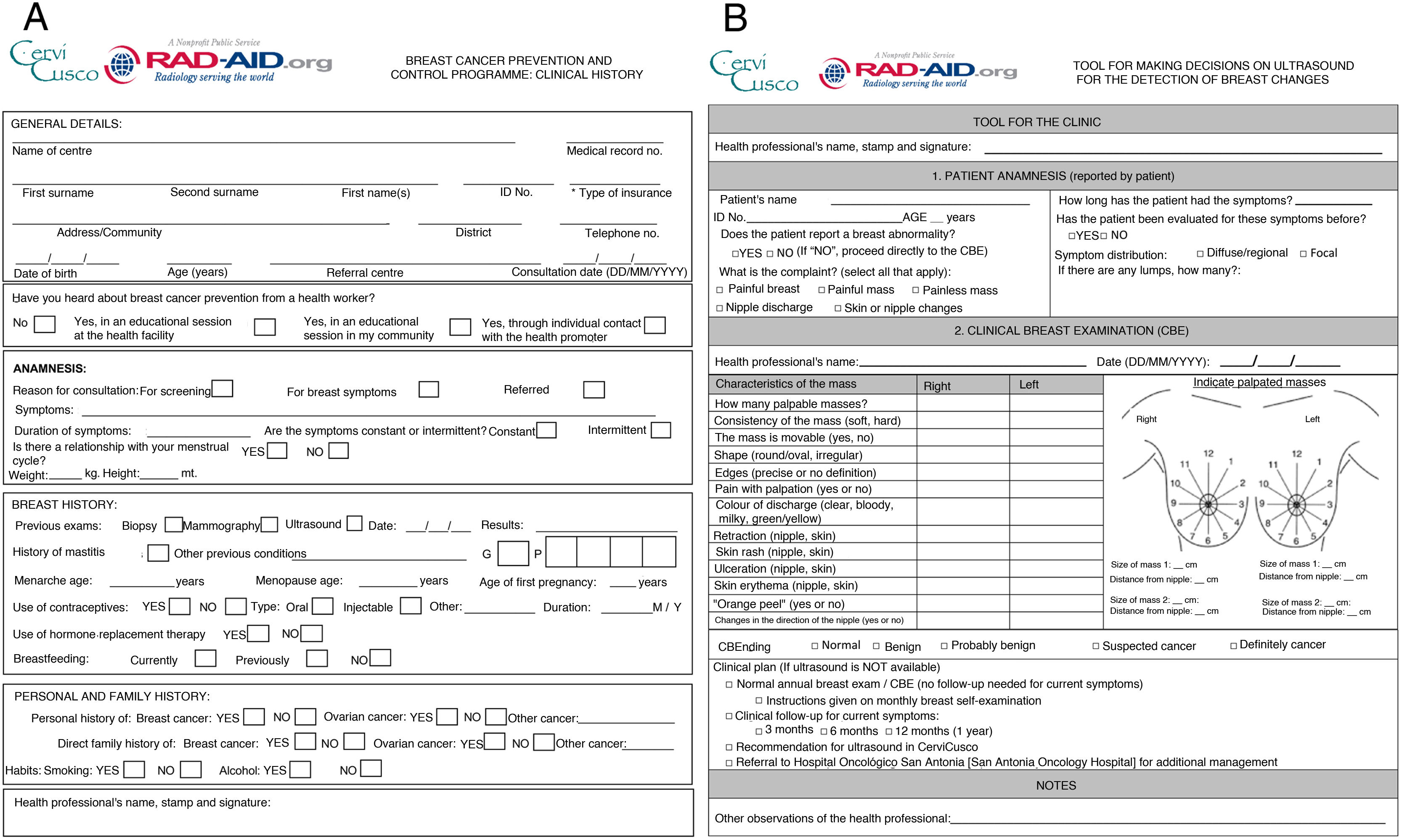

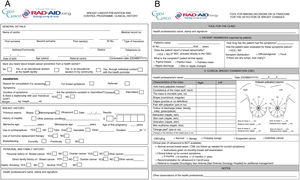

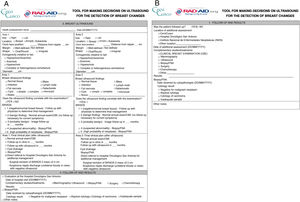

The clinical evaluation forms, including the patient’s history, the documentation of the clinical examination, and the ultrasound findings were optimised in the pilot phase12,13 (Figs. 3 and 4). These documents helped organise and systematise the information from the physical examination and ultrasound. The team that started the programme was in charge of the instructions for using the ultrasound system and the documentation, which was reinforced with the training of local professionals. Lastly, REDCap tools were developed to store medical history documents, along with a decision-making tool based on ultrasound to facilitate the monitoring of basic metrics and quality assurance Ensuring proper transitions from one volunteer team to the next was critical to ensuring that the standard of records was maintained, that efforts were not duplicated, and that patients continued to receive high-quality care. Face-to-face transition was prioritised, but as it could not always be guaranteed, the material was distributed to all volunteers electronically.

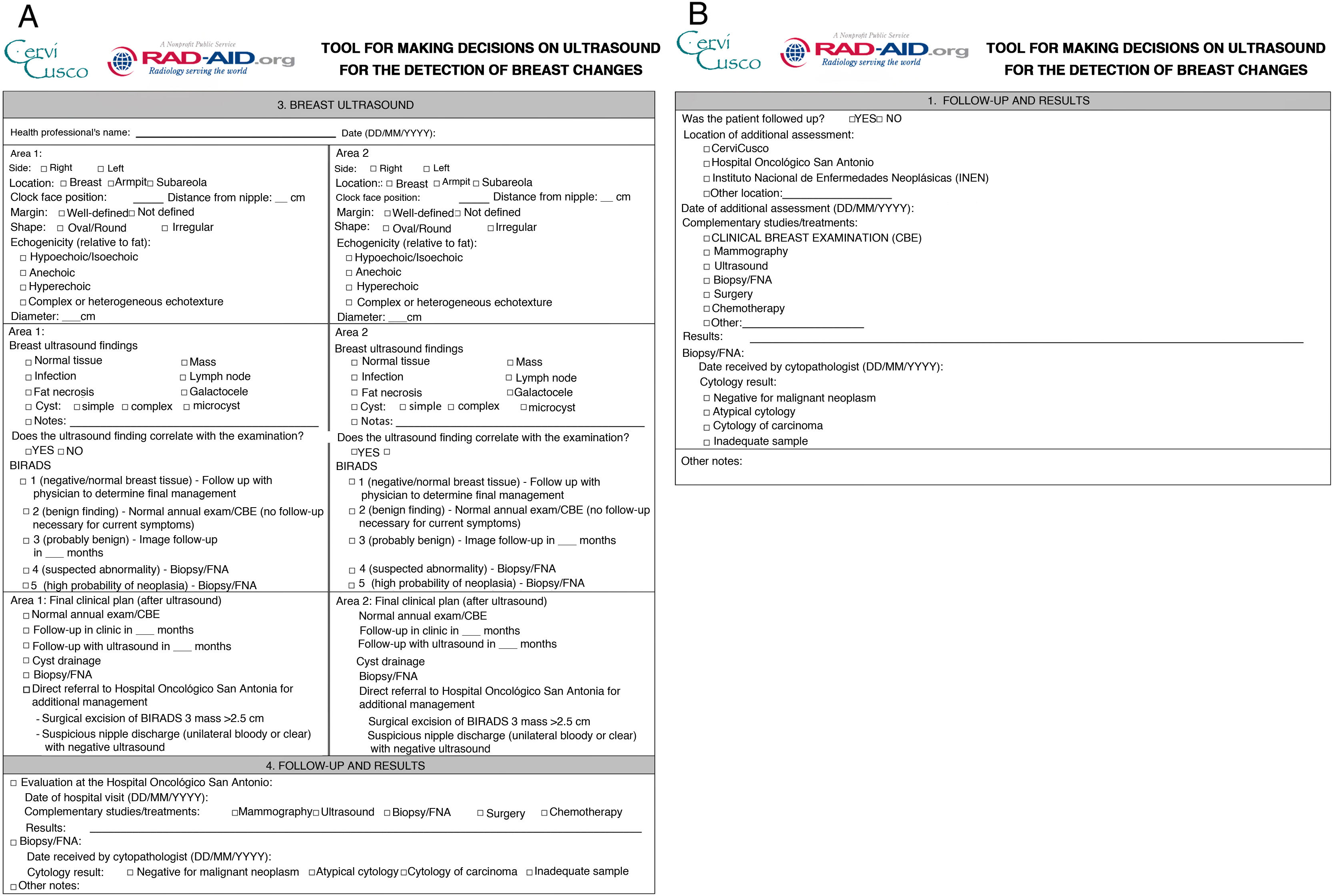

(A and B) Form for collecting breast ultrasound results (A) and management according to the findings (B). The relevance of these forms lies in their importance, on the one hand, as a therapeutic attitude tool, and, on the other, as a registry of cases. The forms are temporarily stored in the CerviCusco clinic, although it is planned that in the future they will be stored in the “cloud”.

The launch of the programme included five weeks of clinical care and staff training and two weeks dedicated to connecting with the community (seven in total). During this period, RAD-AID volunteers gave 26 h of class (14.4 teaching hours and 11.5 h of practice on phantoms) to the CerviCusco staff, and 225 patients were seen, of which 18 ended up being referred to the COR for biopsy or therapeutic decisions. The global results have been previously published.20 SERAMME provided two teams during the launch phase, which, like the rest of the teams, offered their services, one week each, during the months of January and February 2020. Each team consisted of a breast radiologist and a resident with a completed rotation and evaluated in that area. The residents’ travel was financed by the Teaching Unit of the hospital, which considered the rotation to be of teaching interest. The radiologists were financed from the funds of the Radiology Service. Their activity focused on three fundamental tasks: instructing and supervising ultrasounds carried out by the centre’s staff; holding teaching sessions on ultrasound technique and breast semiology; and collaborating in the development of the breast pathology management protocols proposed by RAD-AID. The patients attended with a time interval of approximately 30 min, for approximately eight hours. First, they underwent a full breast history and examination performed by an obstetrician, physician or volunteer. This healthcare provider filled out the RAD-AID structured form with the information collected, including locator data of the breast finding (Fig. 3). Next, our teams performed a bilateral breast and axillary ultrasound in the presence of the centre’s staff, or it was the staff who performed it under the supervision of the SERAMME team (Fig. 5). Finally, in the same form, the part for ultrasound results was completed with specific clinical management instructions, based on the BI-RADS classification (Fig. 4). The consultation was concluded with the results being communicated to the patient. The theoretical seminars focused on the ultrasound semiology of breast nodules and BI-RADS classification (Figs. 5 and 6). At the request of the Cervicusco health services, the second group held practical seminars on the ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy technique (Fig. 5).

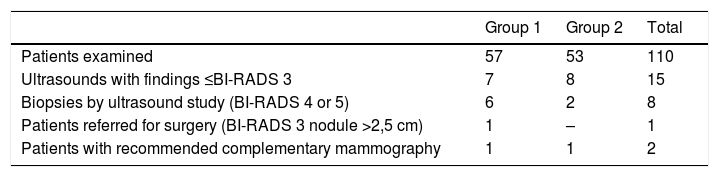

As had been assumed, a large proportion of the women who initially attended were predisposed patients, that is, women less than 40 years old who wanted to be able to undergo screening. Although these women are generally at low risk of cancer, their positive experiences in this early phase are expected to increase public awareness. For example, it is perceived in Peruvian and Latin American women that family, community and personal experiences are important in their behaviour towards health, while negative interaction between the patient and the health provider creates a barrier to receiving cancer care.29,53,59 The processes that the SERAMME teams attended during those two weeks were not mainly neoplastic. Although the pre-established algorithms were very much aimed at detecting palpable nodules, the dominant symptom among the patients seen was uni- or bilateral mastodynia, and the ultrasound examinations were mostly normal (Table 1). This was due to several factors: the US group that opened the programme performed most of the ultrasound scans of patients with palpable nodules detected in the campaigns carried out by CerviCusco in complex geographic areas; patients with suspected nodules had to go to the clinic for the ultrasound study, with the consequent lack of adherence and participation; a large part of the patients seen were not over 40–45 years of age; and lastly, the low awareness of the importance of early diagnosis of breast cancer in the older population. Therefore, as long as the programme only provides ultrasound assistance, and given that we have a portable ultrasound machine, the possibility for the trained personnel to travel during the campaign would facilitate the completion of the study at the time of detection, significantly simplifying logistics and access for patients.

Results of the SERAMME mobile groups.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients examined | 57 | 53 | 110 |

| Ultrasounds with findings ≤BI-RADS 3 | 7 | 8 | 15 |

| Biopsies by ultrasound study (BI-RADS 4 or 5) | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| Patients referred for surgery (BI-RADS 3 nodule >2,5 cm) | 1 | – | 1 |

| Patients with recommended complementary mammography | 1 | 1 | 2 |

SERAMME: Hospital Morales Meseguer Radiology Service.

The high prevalence of acute inflammatory pathologies, especially of granulomatous origin, led to the modification of some of the clinical management protocols, pre-established by RAD-AID. This behaviour was not caused by the ultrasound findings, but by the doubts and uncertainties of the CerviCusco health personnel. For this reason, our opinion is that, in the absence of mammography and without direct access to the biopsy, this different reality forces us to work with a paradigm of containment when facing pathologies with a low-degree of suspicion, that is, to minimise possible false positives.

Future plansRAD-AID intends to evaluate the programme one year after launch, to analyse the results and determine other needs related to technical support, referral systems and training. Reviewing phases I and II will help establish and anticipate the needs. Phase III will focus on scalability, including expanding community engagement, especially with women who will not otherwise have access to cancer screening. Scalability will also depend on an efficient workflow between administrations, nurses, technicians, doctors and other support personnel. It will also be necessary to work in a patient circuit to ensure adequate follow-up and referrals.12,28,38,60

Identifying a local partner that was an established and reputable organisation, such as CerviCusco, was key to this project. But more training is needed for nurses, physicians and community engagement promoters to achieve sustainability, in the hope of retaining those who have already been successfully trained.60 RAD-AID will continue to collaborate with CerviCusco, the COR and the INEN to monitor quality and identify areas for improvement related to teleradiology, pathological anatomy or technical training. The programme and the partners will do an annual review and medical audit of the experiences of patients and personnel, as well as of the results. RAD-AID plans to work with its partners to make the results public, both locally and nationally, and expand it in the medical field through publications, scientific meetings and conferences.

Data collection and monitoring are ongoing to ensure that patient data and follow-up are safe and that referrals can be made effectively.60 It is important to note that, under current conditions, patients who need additional studies will have to wait for the current quarantine conditions to change due to the COVID-19 pandemic.20 With the data transferred to it, REDCap can follow programme activities and monitor quality and results. A cloud-based system that stores and transfers ultrasound images is being established, and artificial intelligence tools (Koios) will be incorporated into the workflow. These measures can help evaluate population data and outcomes, especially in low/middle income countries where, as in Peru, more research is needed on clinical services, outcomes and quality.8,61

The immediate goal of RAD-AID Peru is to do biopsies (FNAB or CNB), which will need personnel to do it, technicians to process the samples and other doctors to interpret the results. In addition, a reliable material supplier will be required, including biopsy needles, and a CerviCusco technician specialised in pathological anatomy will need additional training to process samples in the field.26 It will also be necessary to have a reference person for the interpretation and pathological report, by telepathology or at the COR, to ensure quality and adequate follow-up. Until then, patients will continue to be referred to the COR to collect samples. The long-term goal is mammographic screening. The age groups and frequency will be determined by the results of the project and the possibility of covering a significant part of the population.12,45 CerviCusco will need a lead-lined room to house the mammogram, a trained technician responsible for quality control, and a maintenance contract. The clinic will also need to implement a PACS. Finally, the clinic’s staff is very interested and willing to participate and it is necessary to promote organised continuous training, with structured syllabi in each of the rotations, to avoid repetition of concepts. After returning, the SERAMME group has maintained professional contact to resolve doubts with the CerviCusco staff, pending the resumption of the programme.

ConclusionRAD-AID Peru wants to establish an early detection programme for breast cancer in Cuzco, where access to screening and diagnosis is limited. The participation of local, national and international partners has been critical in the launch phase of the programme, including analysis of radiological resources, public awareness, acquisition of equipment, clinical training and setting up referral networks. This collaboration will continue to be important for the sustainability and scalability of the programme. The regulated participation of a radiology service such as SERAMME makes it possible to offer additional training for its residents in addition to guaranteeing resources for sustained collaboration. For our residents, solving problems with fewer technological resources, attending clinical discussions with CerviCusco staff, and observing their way of working were the highlights of this experience. They also reported that the impression they had was of having learned more than they contributed and it was, above all, a great humbling experience.

The results, quality and achievement of future goals will depend on an objective evaluation of the programme and feedback from stakeholders, in the hope of increasing access to early detection and treatment of breast cancer in the most vulnerable population.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: JS, JMGS.

- 2.

Study concept: JS, JMGS.

- 3.

Study design: JS, JMGS.

- 4.

Data collection: JMGS, JS, MMM, IMGM, JTF, MMG, MHM.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: not applicable.

- 6.

Statistical processing: not applicable.

- 7.

Literature search: MMM, JS, JMGS.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: MMM, JS, IMGM, JTF, JMGS.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: all the authors.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: all the authors.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: González Moreno IM, Trejo-Falcón J, Matsumoto MM, Huertas Moreno M, Martínez Gálvez M, Farfán Quispe GR, et al. Voluntariado radiológico para apoyar un programa de detección precoz del cáncer de mama en Perú: descripción del proyecto, presentación de los primeros resultados e impresiones. Radiología. 2022;64:256–265.