Acute pancreatitis is common and requires multidisciplinary management. The revised Atlanta classification, published in 2012, defines the terminology necessary to enable specialists from different backgrounds to discuss the morphological and clinical types of acute pancreatitis. Radiologists’ role depends fundamentally on computed tomography (CT), which makes it possible to classify the morphology of this disease and to predict its clinical severity by applying imaging severity indices. Furthermore, CT- or ultrasound-guided drainage is, together with endoscopy, the current technique of choice in the initial approach to collections that appear as a complication. This paper aims to disseminate the concepts coined in the revised Atlanta classification and to describe the current role of radiologists in the diagnosis and treatment of acute pancreatitis.

La pancreatitis aguda es una patología frecuente que requiere un manejo multidisciplinar. La revisión de 2012 de la clasificación de Atlanta proporciona la terminología más aceptada en este momento para hablar de sus tipos morfológicos y clínicos entre los distintos especialistas expertos. El papel de la radiología viene dado fundamentalmente por la tomografía computarizada (TC), que permite hacer una clasificación morfológica de esta patología y predecir su gravedad clínica con la aplicación de índices de gravedad por imagen. Además, el drenaje radiológico guiado por TC o ecografía es, junto con el endoscópico, la técnica de elección actual en el abordaje inicial de las colecciones que aparecen como complicación. El objetivo de este trabajo es difundir los conceptos acuñados en la revisión de la clasificación de Atlanta y describir el papel actual del radiólogo en el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la pancreatitis aguda.

Acute pancreatitis is one of the most common causes of hospital admission for gastrointestinal disease and requires multidisciplinary management, especially in its most severe presentations.1 When discussing the different clinical and morphological types, shared terminology is needed for adequate communication between specialists, better classification of patients to offer them the most appropriate treatment, and greater consistency and reproducibility of data in research. The 2012 revision of the Atlanta classification (AC),2 the consensus document—that arose from a working draft available online since 20083 that already included most of the changes to clinical and radiological nomenclature relating to acute pancreatitis (AP) published in 2012—coined the definitions that are currently most internationally accepted in relation to AP and has resulted in a great advance in the standardisation of the nomenclature.

Computed tomography (CT) is still the imaging technique on which AP assessment is based,2 although other techniques such as ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) play complementary roles, especially in the assessment of complications.4,5 For several years, the trend in AP management has been towards minimally invasive procedures, both in the diagnosis of the infection and in the treatment of complications, with radiological techniques playing a significant role.

This work will look at recent publications, reviewing the terminology proposed by the revised AC for the morphological and clinical types of AP (emphasising certain areas of improvement) and the utility of radiology in assessing its complications, and discussing current trends and future perspectives for its treatment.

Morphological classification of acute pancreatitis according to the revised Atlanta classificationThe AC establishes two morphological types of AP2,6,7:

- •

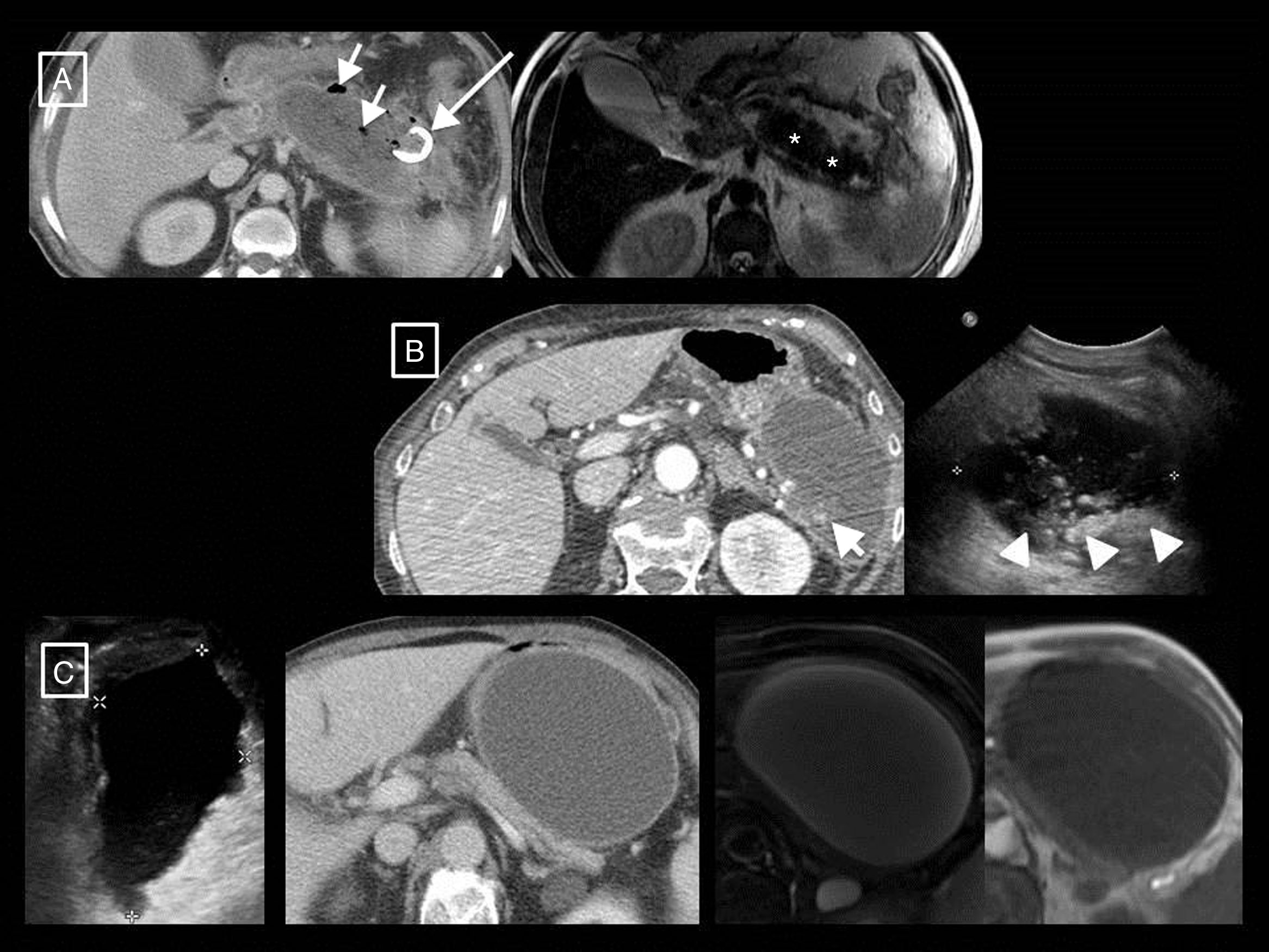

Interstitial oedematous pancreatitis (Fig. 1): the most common, causing non-necrotising inflammation of the pancreas. In contrast CT, the gland often displays focal or diffuse enlargement and enhancement that is generally homogeneous but can sometimes be heterogeneous due to oedema. Peripancreatic fat may appear striated and small quantities of peripancreatic fluid may be seen (see section on pancreatic and peripancreatic collections). Symptoms tend to resolve in the first week.

Figure 1.Examples of interstitial oedematous pancreatitis. (A) Increased size and poorly defined borders of the head of the pancreas (asterisk). (B) Another case with greater striation of the peripancreatic fat (short arrows) and minimally heterogeneous pancreatic enhancement caused by interstitial oedema. (C) Diffuse increase in size and homogeneous enhancement of the pancreas, a small acute peripancreatic fluid collection around the tail (long arrow).

(0.25MB). - •

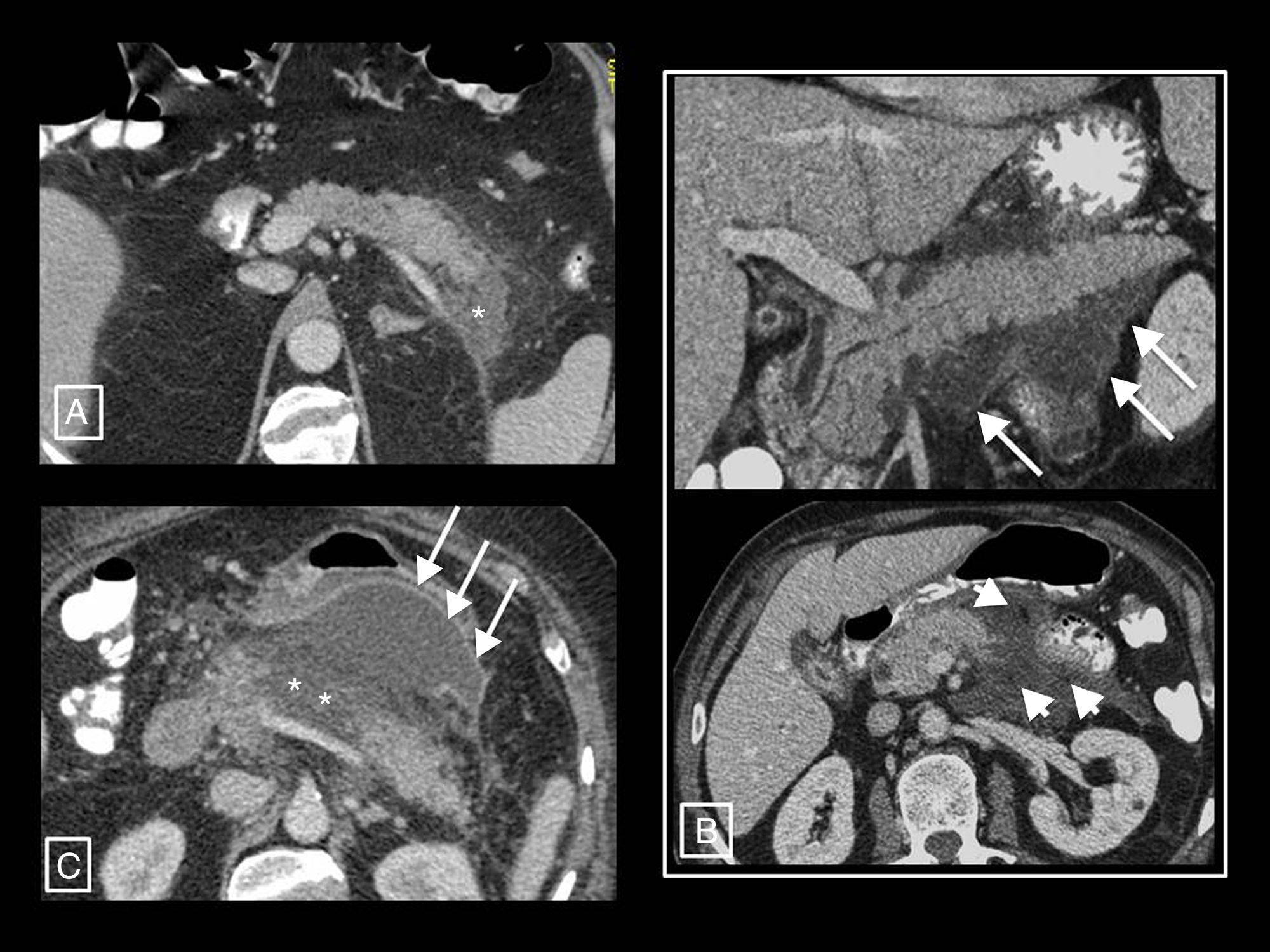

Necrotising pancreatitis (Fig. 2): accounts for 5% to 10% of AP and can be pancreatic (5%), peripancreatic (20%) or both (75%). In contrast CT, pancreatic necrosis manifests as one or more areas of hypodensity in the parenchyma, while in peripancreatic necrosis the pancreas enhances normally but the peripancreatic tissues develop necrosis (see section on pancreatic and peripancreatic collections). Patients with isolated peripancreatic necrosis have higher morbidity and mortality rates than those with interstitial oedematous pancreatitis, but lower than those with glandular necrosis. The natural course of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrosis is variable, as it may remain solid or become fluid, may remain sterile or become infected, and may persist or disappear with time.

Figure 2.Necrotising pancreatitis. (A) Pancreatic necrosis: hypodensity of the tail of the pancreas with respect to the rest of the gland (asterisk) compatible with necrosis. (B) Peripancreatic necrosis: the pancreas presents full and homogeneous enhancement, but is surrounded by a partially encapsulated (long arrows) collection with heterogeneous content due to hypodense solid elements in fluid (short arrows) indicative of necrosis. (C) Pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis: glandular necrosis (asterisks) and necrosis of the peripancreatic tissues forming a collection anterior to the pancreas (arrows).

(0.34MB).

The AC differentiates between collections that can appear as a complication of AP based on their content and time of evolution (taking the appearance of the first symptoms as a starting point)2,6,7 (Table 1, Fig. 3):

- •

Acute peripancreatic fluid collection. This is a collection that appears in interstitial oedematous pancreatitis during the first 4 weeks of evolution. It is always found adjacent to the pancreas and is characterised in that it only contains fluid (by definition it lacks the solid components that would indicate necrosis), its density is homogeneous, it has no defined wall and it conforms to the fascial planes of the retroperitoneum (peripancreatic sheath, anterior pararenal spaces, etc.).

- •

Pseudocyst. This refers to a collection that appears in interstitial oedematous pancreatitis that persists for more than 4 weeks from the start of symptoms. It is thought that it appears due to disruption of the main pancreatic duct or its branches. In CT, it appears as a round or oval-shaped collection, in this case with a well-defined wall, containing only homogeneously hypodense fluid without solid inclusions. The development of pseudocysts in AP (unlike what happens in chronic pancreatitis) is very rare (most persistent peripancreatic collections in AP contain necrotic material), so it is thought that this term may fall into disuse in the context of AP.

- •

Acute necrotic collection. This is a collection that appears in interstitial oedematous pancreatitis during the first 4 weeks of evolution. The necrosis may affect the pancreatic parenchyma and/or the peripancreatic tissues and is due to the release of pancreatic enzymes that cause digestion, saponification of fat and its necrosis. In CT, it appears as intra- and/or extrapancreatic collections that may be several in number, often with a loculated or septated morphology, none completely delimited by a defined wall, and with a characteristically heterogeneous density due to containing both fluid and solid material indicative of necrosis.

- •

Walled-off necrosis. This is a collection that persists beyond 4 weeks in necrotising pancreatitis and consists of necrotic tissues contained inside a capsule of reactive inflammatory tissue with increased uptake. It appears as completely walled-off intra- and/or extrapancreatic collections with heterogeneous density due to the presence of both fluid and solid content.

Types of collections in acute pancreatitis.

| Time of evolution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤4 weeks | >4 weeks | |||

| Solid or semisolid content (indicative of necrosis) | No | Acute peripancreatic fluid collection | Pseudocyst | Interstitial oedematous pancreatitis |

| Yes | Acutenecrotic collection | Walled-off necrosis | Necrotising pancreatitis | |

Types of collections in acute pancreatitis. (A) Acute peripancreatic fluid collection (APFC) is a homogeneous fluid collection that conforms to the spaces and fascial planes (long arrows). (B) Pseudocyst is the result of an APFC persisting over time, giving rise to a collection that remains homogeneously fluid but is completely surrounded by a capsule of granulation tissue (short arrows). (C) Acute necrotic collection (ANC) is characterised by its heterogeneous content, made up of fluid mixed with solid or semisolid elements (short arrow). It may be partially walled-off (long arrows). (D) When an ANC persists for more than 4 weeks and becomes fully walled-off (long arrows), it is called walled-off necrosis. Hypo- and hyperdense solid elements can be seen within it (short arrows) mixed with fluid.

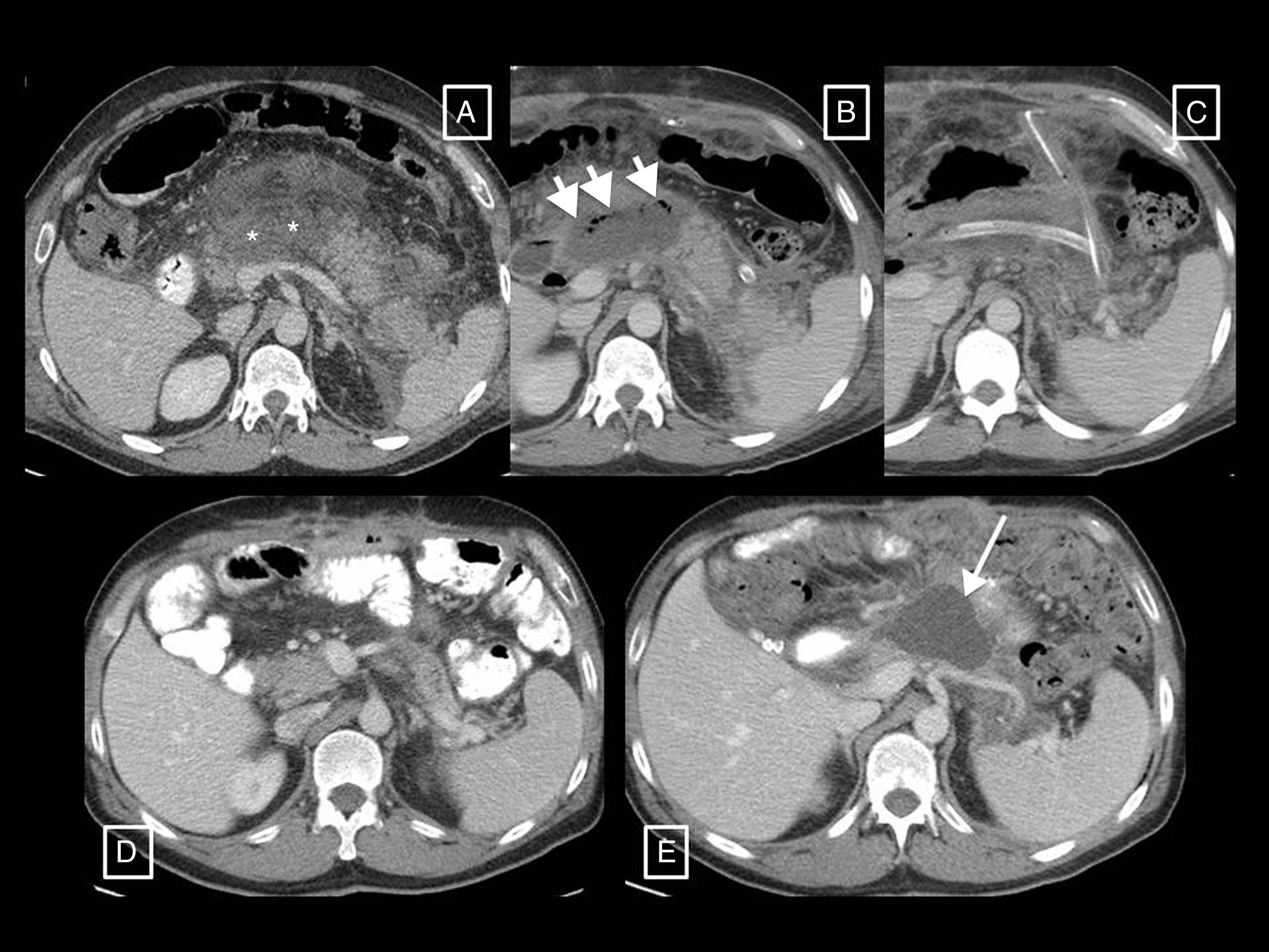

The AC also coins the term post-debridement pseudocyst2,6,7 to refer to a collection that can appear in the debridement bed after removing walled-off necrosis content. The cavity refills with pancreatic juices that leak from the remaining secretory tail that communicates with the bed in what is known as disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome (Fig. 4). It often forms months or even years after the onset of AP, and is the only case in which pseudocysts are associated with necrotising pancreatitis.

Post-debridement pseudocyst. Patient with necrotising pancreatitis who in the initial computed tomography (CT) (A) presented central necrosis of the pancreas (asterisks), later developing walled-off necrosis that was then superinfected (B, short arrows). The post-debridement CT (C) shows Martín Palanca catheters in the bed. Follow-ups over the following months (D) show resolution of the collection. However, 4 months after the debridement (E), the collection reoccurred (long arrow), filled with homogeneous fluid corresponding to pancreatic juices secreted by the viable tail due to disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome. This recurring collection is a post-debridement pseudocyst.

Other terms previously used, such as pancreatic abscess, necroma or pancreatic sequestration, are now obsolete.

Clinical classification of acute pancreatitis according to the revised Atlanta classificationThe AC differentiates between two phases in the evolution of this disease2,6,7:

- •

Early phase: This generally comprises the first week of the process, in which AP manifests as a systemic inflammatory response. The severity of the pancreatitis and its treatment will therefore essentially depend on clinical parameters, specifically whether organ failure occurs and its duration. Although local complications can occur in this phase, it has been found that the extent of the morphological changes in AP at this point does not necessarily correlate with its clinical severity.

- •

Late phase: From the second week, although it may last weeks or months. By definition, it occurs only in patients with moderate or severe AP and is characterised by the persistence of systemic inflammatory findings or the presence of local or systemic complications, so treatment at this point will be based on both clinical and radiological criteria. Thus, although the main determiner of severity will continue to be persistent organ failure, it will be important to distinguish between the different types of local complications in imaging due to the implications doing this will have in patient management.

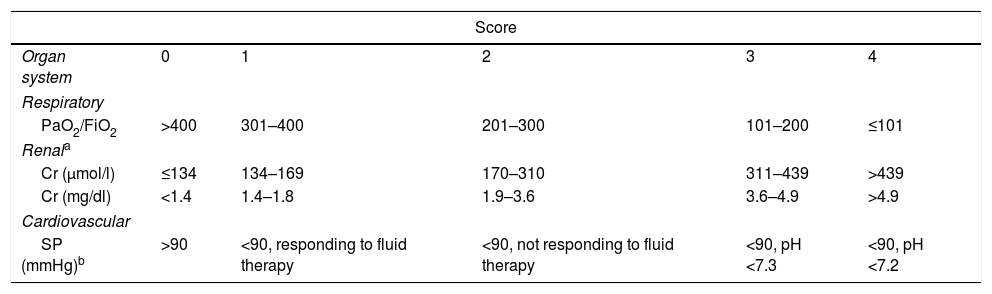

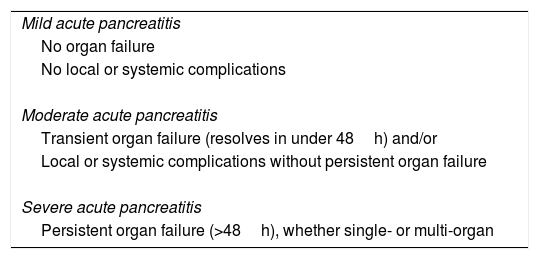

The AC defines local and systemic complications.2 The former include peripancreatic complications (acute peripancreatic fluid collection, pseudocyst, acute necrotic collection or walled-off necrosis), functional alteration in gastric emptying, splenic or portal vein thrombosis and colonic necrosis. The exacerbation of pre-existing comorbidities (coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) triggered by AP is considered a systemic complication. On the other hand, following the modified Marshall scoring system8 (Table 2), the AC distinguishes between transient (resolving in the first 48h), persistent (persisting beyond 48h) and multiple (affecting more than one organ or system) organ failure. The types of complications and organ failure are taken into account when determining severity based on the following categories (Table 3):

- •

Mild. AP does not involve organ failure or local or systemic complications. These patients can often be discharged during the early phase, do not usually require imaging tests and associated mortality is very rare.

- •

Moderate. AP involves transient single or multiple organ failure or local or systemic complications. It may resolve without intervention (e.g. if there is transient organ failure or an acute peripancreatic fluid collection) or require prolonged specialist care (as in the case of extensive sterile necrosis), and its mortality, although higher than for mild AP, is much lower than for severe AP.

- •

Severe. AP involves persistent single or multiple organ failure. Patients who develop it often have one or more associated local complications, and those that do so in the first few days have an increased risk of mortality of up to 36–50%. The development of infected necrosis in these patients is associated with extremely high mortality.

Modified Marshall scoring system for the definition of organ failure.

| Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ system | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Respiratory | |||||

| PaO2/FiO2 | >400 | 301–400 | 201–300 | 101–200 | ≤101 |

| Renala | |||||

| Cr (μmol/l) | ≤134 | 134–169 | 170–310 | 311–439 | >439 |

| Cr (mg/dl) | <1.4 | 1.4–1.8 | 1.9–3.6 | 3.6–4.9 | >4.9 |

| Cardiovascular | |||||

| SP (mmHg)b | >90 | <90, responding to fluid therapy | <90, not responding to fluid therapy | <90, pH <7.3 | <90, pH <7.2 |

| For unventilated patients, FiO2 can be estimated as follows: | |

|---|---|

| Supplemental oxygen (l/min) | FiO2 (%) |

| Ambient air | 21 |

| 2 | 25 |

| 4 | 30 |

| 6–8 | 40 |

| 9–10 | 50 |

Note: A score of 2 or more for any system defines the presence of organ failure.

Severity of acute pancreatitis according to the revised Atlanta classification.

| Mild acute pancreatitis |

| No organ failure |

| No local or systemic complications |

| Moderate acute pancreatitis |

| Transient organ failure (resolves in under 48h) and/or |

| Local or systemic complications without persistent organ failure |

| Severe acute pancreatitis |

| Persistent organ failure (>48h), whether single- or multi-organ |

This clinical classification has also resulted in an advance in the standardisation of the nomenclature; however, some factors with a considerable impact on patient evolution, such as thrombosis-type arterial vascular complication or pseudoaneurisms, have suffered from a lack of detailed consideration.9 The AC does mention, after classifying the degrees of severity of AP, that fistulisation to the gastrointestinal tract or the different natures of the various types of peripancreatic collection will be extremely important as they require different management,2 but these differences do not influence the severity classification of patients despite being aspects with a different prognosis (e.g. an acute peripancreatic fluid collection and an acute necrotic collection do not have the same evolution or consequences) that probably should be included in the severity determination in future revisions.9 The same occurs with necrosis infection, as the AC states that it is a marker for increase risk of death and that this risk is different in patients with and without persistent organ failure,2 but its presence or absence likewise does not alter the severity classification. In this regard, in 2012, the Determinant-based Classification (DBC),10 another international, multidisciplinary AP classification, defined glandular or peripancreatic necrosis and organ failure as local and systemic severity determinants, respectively, and classified AP as mild, moderate, severe or critical; the last involves concurrent infected necrosis and persistent organ failure. Nevertheless, some work has been published that did not find significant differences in patient outcomes based on whether the AC or DBC was used.11

Radiology's role in assessing the severity of acute pancreatitisAP diagnosis requires two of the following three criteria2,12: (a) clinical (suggestive pain), (b) analytical (serum amylase or lipase levels three times higher than the upper limit of normal) and/or (c) radiological (AP criteria in CT—see section on morphological types of acute pancreatitis—MRI or ultrasound). CT continues to be the main imaging technique for assessing AP, being performed in the initial assessment only in cases of uncertain diagnosis of acute abdomen (when the clinical and analytical criteria are not met, as if they are met and there are no clinical severity criteria imaging tests will not be needed), when there are clinical predictors of severe AP or if the initial response to conservative treatment fails or there is clinical deterioration.12 The optimum time to do it is at least 72h after the onset of symptoms,12 as necrosis can take this long to become established and visible on imaging13; a CT performed too early may underestimate it (Fig. 5). In follow-up, CT will be performed if the patient does not improve or worsens, or if invasive treatment is planned.12

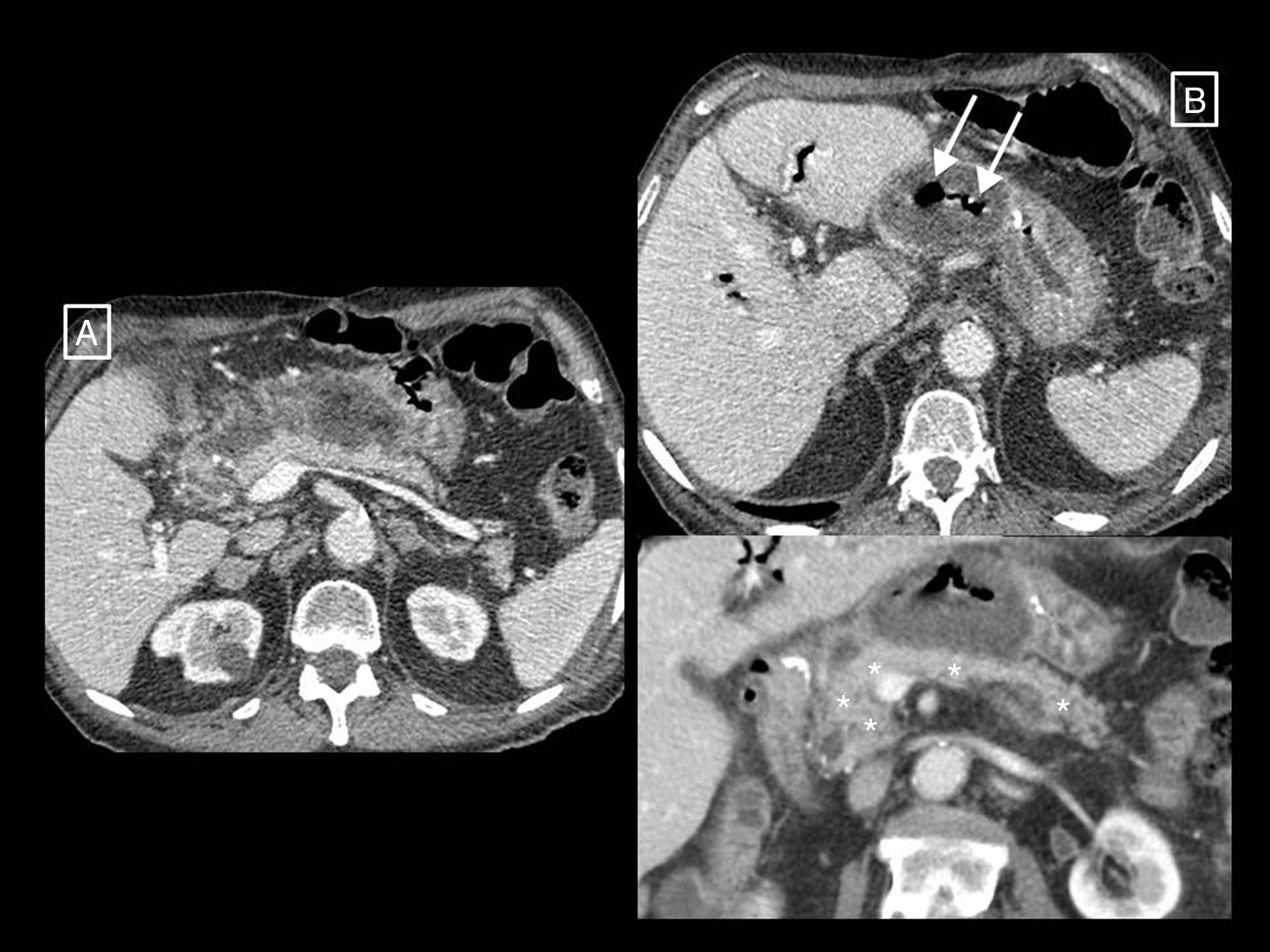

Example of how computed tomography (CT) performed too early can underestimate necrosis in acute pancreatitis. This CT study (image column A), performed on the day of onset of abdominal pain, showed a pancreas increased in size without areas suggestive of necrosis and with acute peripancreatic fluid collections (long arrows). The control performed 10 days later (image column B) clearly shows an area of glandular necrosis (asterisk) and increased collections, which are partially walled-off (long arrows) and contain fatty solid elements (short arrows) making them compatible with acute necrotic collections.

There is a good deal of variability in the scientific literature regarding the technical protocol to use, but in general thin slices (≤5mm), with 100–150ml of non-ionic intravenous contrast administered at 3ml/s, to obtain a pancreatic (35–40s delay) and/or portal phase (50–70s delay) are recommended.12 For follow-up, the portal phase may suffice, and multi-phase studies are only performed if haemorrhage, arterial pseudoaneurysm or mesenteric ischaemia are suspected.12

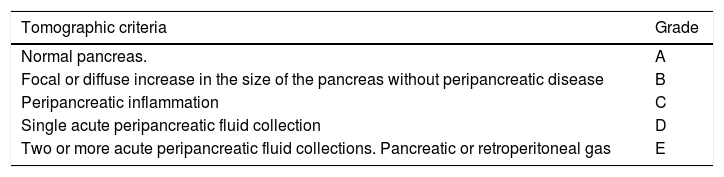

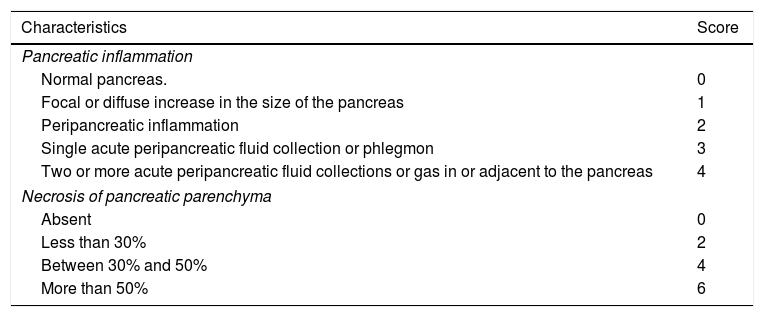

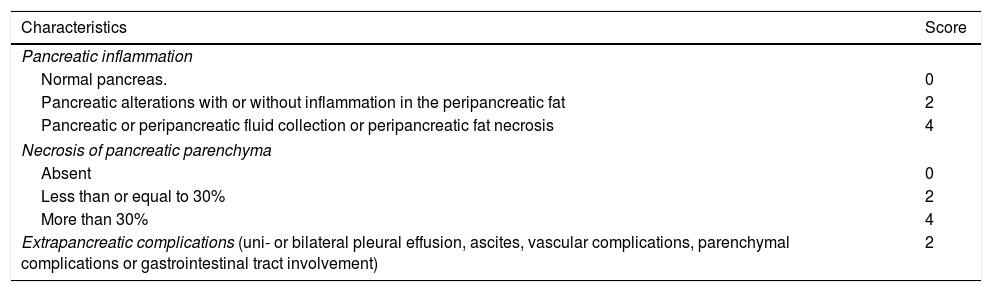

The fundamental role of CT in assessing the severity of AP will be to determine the presence of local complications, the extent of necrosis and superinfection. Radiological scoring systems have been used for some years to predict the clinical severity of AP13 and thus be able to take earlier and more radical measures in the case of severe AP on imaging. The most widespread have been the Balthazar score, published in 198514 (Table 4), based on pancreatic/peripancreatic inflammation data and the presence of collections, and the CT severity index (CTSI), also described by Balthazar et al. in 199015 (Table 5) which also takes into account the extent of any pancreatic necrosis. Although the latter is the most popular of all, some authors claim16 that it has only demonstrated moderate interobserver concordance, without a clinically significant correlation with the development of organ failure. Other authors17 have suggested a significant correlation between severe AP and the presence and extent of extrapancreatic collections, and cases of severe AP with Balthazar grades of D or E without pancreatic necrosis have been found.18 This all highlights the prognostic importance of necrosis of the extrapancreatic tissues.19 In this vein, in 2004 Mortele et al. published the modified CTSI16 (Table 6), which in addition to the CTSI parameters, scores peripancreatic fat necrosis and considers extrapancreatic complications (pleural effusion, ascites, vascular complications, gastrointestinal tract involvement), demonstrating greater correlation than the CTSI with length of hospital stay and development of organ failure.16 Both the CTSI and the modified CTSI have been found to have good concordance with the clinical severity classification according to the AC.20 Nevertheless, when using the standardised nomenclature coined by the AC, the modified CTSI calculation (which scores terms similar to those established by the AC such as “pancreatic or peripancreatic fluid collection” of “peripancreatic fat necrosis”, see Table 6) appears to be simpler and more reproducible than that of the CTSI (which used other more ambiguous and unstandardised terms such as “one or more poorly defined fluid collections” or obsolete terms such as “phlegmon”, see Table 5). Studies such as that by Heiss et al.,21 which find significantly higher mortality in the presence of remote collections (in the paracolic gutters and posterior pararenal spaces, especially the left) than in the absence of these, and other more recent works such as that by Meyrignac et al.,22 based on the quantitative assessment of extrapancreatic necrosis, continue to seek severity predictors in imaging, most recently using the updated AC terminology. This terminology has certainly demonstrated good interobserver concordance, reaching very good among expert radiologists.23

Balthazar grades.

| Tomographic criteria | Grade |

|---|---|

| Normal pancreas. | A |

| Focal or diffuse increase in the size of the pancreas without peripancreatic disease | B |

| Peripancreatic inflammation | C |

| Single acute peripancreatic fluid collection | D |

| Two or more acute peripancreatic fluid collections. Pancreatic or retroperitoneal gas | E |

Computed tomography severity index.

| Characteristics | Score |

|---|---|

| Pancreatic inflammation | |

| Normal pancreas. | 0 |

| Focal or diffuse increase in the size of the pancreas | 1 |

| Peripancreatic inflammation | 2 |

| Single acute peripancreatic fluid collection or phlegmon | 3 |

| Two or more acute peripancreatic fluid collections or gas in or adjacent to the pancreas | 4 |

| Necrosis of pancreatic parenchyma | |

| Absent | 0 |

| Less than 30% | 2 |

| Between 30% and 50% | 4 |

| More than 50% | 6 |

Note: Using this scoring system, the severity of pancreatitis for each patient is classified as mild (0–3 points), moderate (4–6 points) or severe (7–10 points).

Modified computed tomography severity index.

| Characteristics | Score |

|---|---|

| Pancreatic inflammation | |

| Normal pancreas. | 0 |

| Pancreatic alterations with or without inflammation in the peripancreatic fat | 2 |

| Pancreatic or peripancreatic fluid collection or peripancreatic fat necrosis | 4 |

| Necrosis of pancreatic parenchyma | |

| Absent | 0 |

| Less than or equal to 30% | 2 |

| More than 30% | 4 |

| Extrapancreatic complications (uni- or bilateral pleural effusion, ascites, vascular complications, parenchymal complications or gastrointestinal tract involvement) | 2 |

Note: Using this scoring system, the severity of pancreatitis for each patient is classified as mild (0–2 points), moderate (4–6 points) or severe (8–10 points).

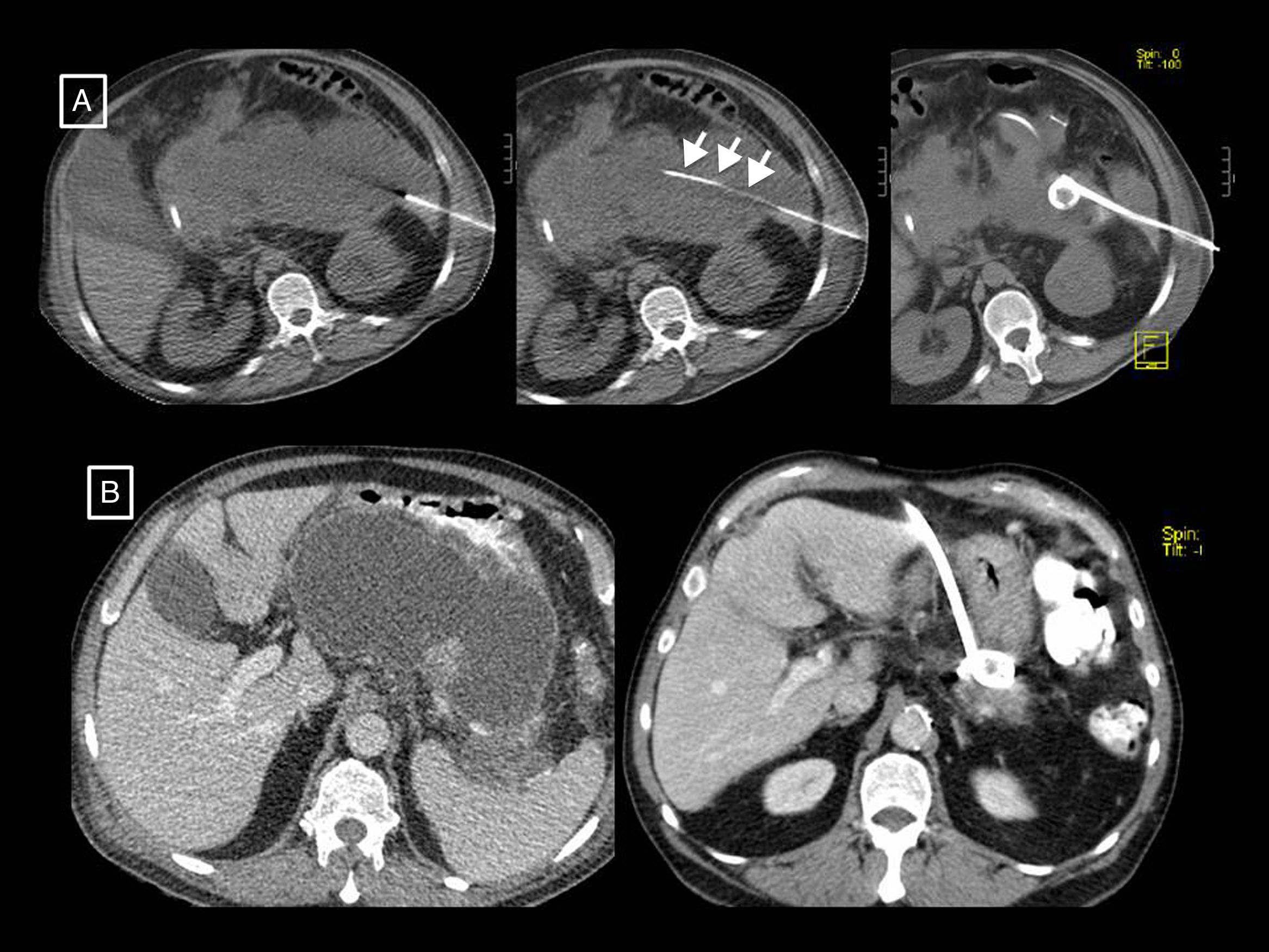

Another extremely useful, although less readily available, imaging technique in AP assessment is MRI. T1- and T2-weighted sequences without and with fat saturation (the latter has the advantage of allowing better differentiation between collections and retroperitoneal fat) and 3D T1-weighted gradient-echo before and after administering intravenous contrast12 will provide the same information as a CT in terms of severity, but with higher tissue resolution when differentiating the content of collections. In fact, both T2-weighted MRI and B-mode ultrasound will be indicated when it is clinically relevant to differentiate between a pseudocyst and necrotic collection and CT cannot distinguish them12 (Fig. 6). In addition, adding MR cholangiography sequences will enable the existence of duct obstruction, dilation, anatomical variants or complications such as disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome to be assessed.24 Ultrasound continues to be the initial technique for diagnosing lithiasic aetiology, and contrast ultrasound has been described as an alternative to CT for detecting pancreatic necrosis and predicting the clinical course of the disease4, although this technique is not included in most guidelines.

Examples of the greater tissue resolution of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound in differentiating solid and fluid content of collections in acute pancreatitis. (A and B) Walled-off necrosis in two patients. In the first, the T2-weighted MRI shows better than the computed tomography (CT) that most of the collection is formed by the necrosed tail of the pancreas (asterisks). However, the greater sensitivity and specificity of CT with respect to MRI can be seen with regard to the small gas bubbles (short arrows), in this case secondary to a radiological catheter (long arrow). In the second, although the CT shows some dense solid foci in the interior (short arrow), the ultrasound shows them more clearly and in greater number (arrow heads). In this other patient (C; same as Fig. 3B) we can see from left to right the homogeneous appearance of a growing pseudocyst in the ultrasound, CT and T1- and T2-weighted MRI. In ultrasound, pseudocysts may show fine echos in their interior, but never clearly solid elements such as those in example (B(.

With regard to infection, this occurs in up to 30% of necrotising pancreatitis cases, and its detection is important due to the need for antibiotic treatment and the potential invasive treatment it may require.2 In day-to-day practice, its diagnosis is based on clinical (fever, elevated serum inflammatory markers, new-onset organ failure) or radiological (presence of pancreatic or peripancreatic extraluminal gas in CT) criteria (Fig. 7) or a positive culture or Grams stain result after a fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB).2,25 In the past, suspected infection had to be confirmed by FNAB and an elective debridement performed if necessary.26,27 However, FNAB's utility is currently disputed. van Baal et al.25 or the guidelines of the Acute Pancreatitis Working Group of the International Association of Pancreatology and the American Pancreatic Association12 argue that, in most cases, clinical and radiological signs are sufficiently precise to diagnose superinfection. Others, such as Freeman et al.28 or the guideline of the American College of Gastroenterology29 argue that under current trends early intervention is avoided, and if it is done, it is with minimally invasive endoscopy or percutaneous drainage techniques that can be used to obtain samples for culture without first needing a diagnostic biopsy. In addition, necrosis with suspected superinfection can be treated with empirical antibiotics alone (without needing FNAB) if there are no signs of sepsis.28,29 Rates of false negatives as high as 25% have also been described, as has the risk of the biopsy itself introducing infection.25 To conclude, the indications for FNAB have been narrowed to those patients without clear clinical or radiological signs of infection who do not improve after several weeks,12,25 or suspected fungal superinfection in patients in whom antibiotic therapy does not improve fever or leukocytosis.28,29

Infected peripancreatic necrosis. In the first study (A), signs of only peripancreatic necrotising pancreatitis can be seen in the form of a poorly defined heterogeneous collection anterior to the head and body of the pancreas compatible with an acute necrotic collection. In a follow-up performed due to fever after more than 4 weeks from the onset of symptoms (B), the collection is seen to be completely walled-off (walled-off necrosis) and gas bubbles (long arrows) compatible with superinfection have appeared. In the inferior coronal reconstruction, the normally enhanced pancreas can be seen (asterisks).

Other recently studied non-invasive methods to detect infection in AP are diffusion-weighted MRI5,30 and positron-emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) with 18F-FDG-labelled leukocytes,31 with good preliminary results.

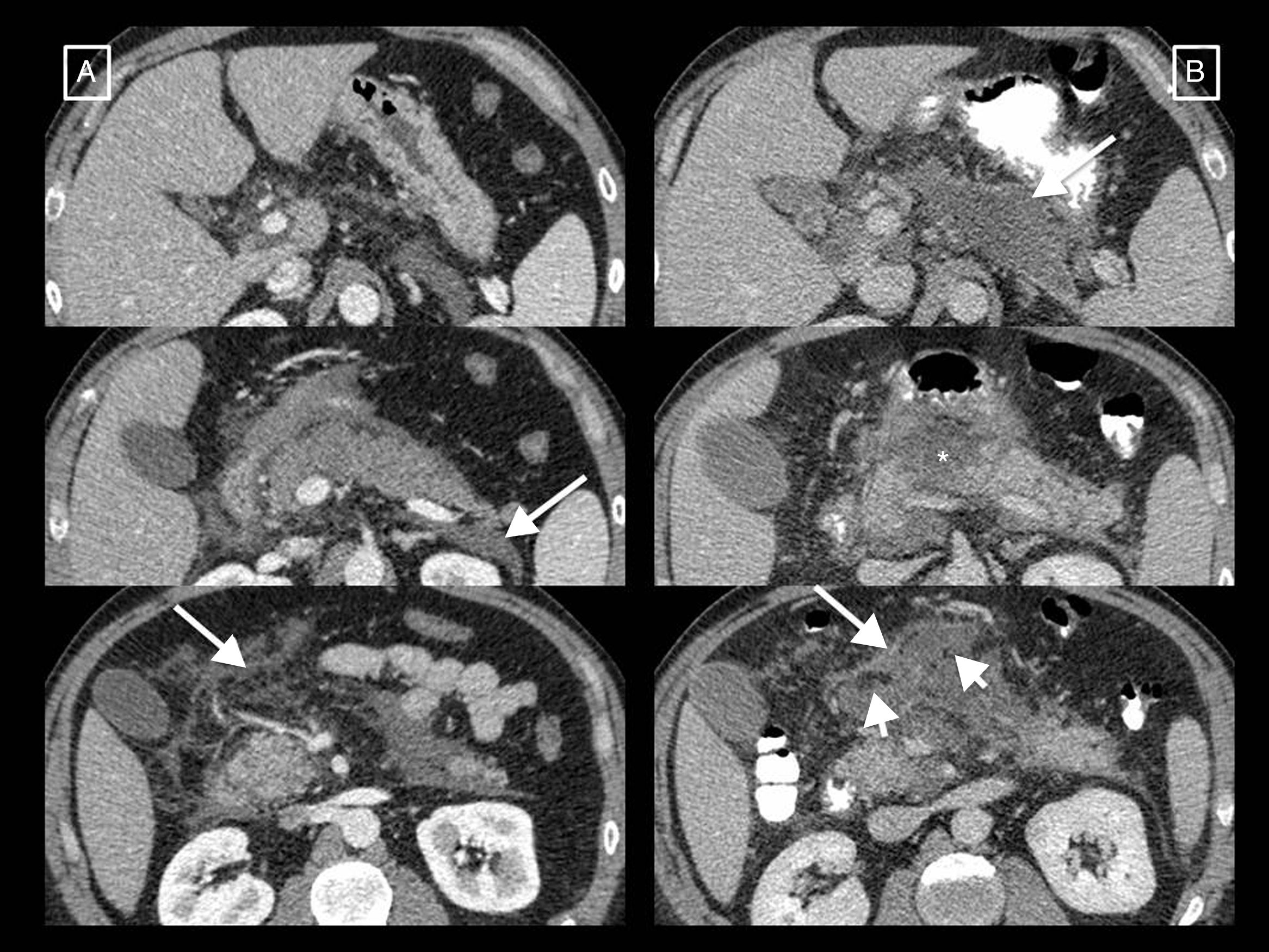

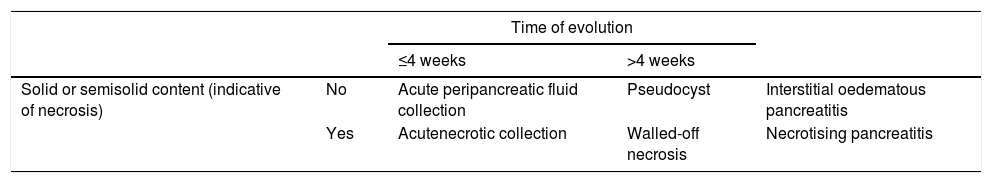

Radiology's role in the treatment of complicationsThe role of radiological techniques in the treatment of complications of AP is to monitor treatment and serve as guidance for draining collections. Over the years, there has been a change in the management of complicated AP in terms of indications, timeline and approach.32 Historically, many cases of sterile necrosis underwent intervention, whereas the main indication nowadays in infection. We have moved from early debridement to deferred intervention, after at least 4 weeks, giving collections a chance to wall off, which has been found to have lower morbidity and mortality. The current trend is towards minimally invasive treatment as opposed to the classic open surgical debridement that has been relegated to last-place therapeutic option. The turning point for this change of paradigm was in 2010, with the publication of the results of the PANTER randomised clinical trial.33 This study demonstrated that, compared to open debridement, a minimally invasive phased approach based on percutaneous drainage as the first-line intervention, followed or not by video assisted retroperitoneal debridement (known as percutaneous/surgical “step-up approach”), reduced the rate of major complications and death in patients with infected necrotising pancreatitis, and that more than one third were successfully treated with drainage and did not require major surgery. Several studies were later published that also demonstrate that most patients with necrotising pancreatitis can be managed conservatively,32,34,35 and that a considerable number of the rest (up to 55.7%) can be treated with radiology-guided drainage without the need for debridement34 (Fig. 8). If necessary, drainage would allow sepsis to be controlled and surgery delayed, allowing the necrotic tissue to become better delimited and thus minimising resection of viable tissue, decreasing postoperative adverse effects and improving long-term pancreatic endocrine and exocrine function.28 Subsequently, in 2012, the PENGUIN study36 compared transgastric endoscopic debridement with video assisted retroperitoneal surgical debridement, finding that with endoscopy the proinflammatory response was reduced and the rates of death and major complications, including organ failure, were lower. Since then, the endoscopic step-up approach has been gaining popularity in parallel with the percutaneous/surgical step-up approach discussed above. In 2018, the TENSION trial37 concluded that both approaches are equally valid, but that the lower rate of pancreatic fistulas and shorter length of stay associated with the endoscopic approach probably make this the approach to start with in places where both options are available. At our centre, where endoscopic debridement is not available, percutaneous drainage is the technique of choice for the treatment of complications. Radiology-guided drainage of collections is technically feasible in 95% of cases,12 and its indications are12 necrotising pancreatitis with suspected infection and clinical deterioration (main indication) or with organ failure than persists for several weeks even in the absence of signs of infection, and exceptionally, sterile necrotising pancreatitis when there is an obstruction to gastric emptying or an intestinal or biliary obstruction caused by the necrotic mass, persistent pain or malaise, or in case of persistently symptomatic disconnected pancreatic duct. The procedure can be performed with CT or ultrasound guidance and the Seldinger or direct puncture technique, if possible using a retroperitoneal approach via the left anterior pararenal space (Fig. 8A), although a transperitoneal or transgastric trajectory may be chosen if considered more accessible and/or safe for the patient (Figs. 8B and 9). In our experience, large-gauge (12–16F) self-retaining catheters are used to maximise drainage, although it is true that there are no studies indicating what calibres to use first or confirming that larger calibres result in better outcomes37; placing several drains can even help to create a flushing system for the drained cavity. Regular care of the mechanism by nursing staff, including flushing and aspiration each shift (10cc of normal saline solution every 8h), as well as by the radiologist every 24–48h, is very important to avoid obstruction. If this should occur, the tube should be changed and only if the patient does not then improve, which happens in rare cases, should surgical debridement be considered. To date, it has been the norm to wait 4 weeks from the onset of symptoms to drain collections, but the right time to drain is disputed, especially when radiology-guided drainage is used as the first-line treatment strategy.38 The ongoing POINTER trial39 seeks to clarify whether it is also necessary to wait 4 weeks to drain or if doing so earlier could reduce complications and length of hospital stay. Its results are expected in 2019.

Two examples of necrotising pancreatitis that resolved with radiology-guided drainage alone. (A) In the first patient, from left to right, we can see a drainage tube inserted using the Seldinger technique with a classic approach via the left anterior pararenal space, first inserting the initial puncture needle inside the collection, passing a guidewire through it (short arrows) and, following the respective dilators (not shown), leaving in place a 12F catheter. (B) In the second patient we can see how a large walled-off necrosis was resolved thanks to radiology-guided drainage, in this case using a right anterior subcostal approach and a 14F tube.

Two further examples of necrotising pancreatitis that resolved with radiology-guided drainage alone. (A) In the first patient, a large necrotic collection can be seen, anteriorly surrounding the pancreas and extending into the left anterior pararenal space. A first more anterior and medial catheter was inserted in this (short arrow) but did not resolve the collection alone. Another posterior lateral catheter (long arrow) was therefore inserted later. The introduction of contrast through these catheters (image on right, axial oblique MRI reconstruction) showed that they were effectively draining interconnected areas, thereby creating a flushing system for the cavity, with one tube for the entry of saline and the other for drainage of the necrosis, which was eventually resolved. (B) Patient with clinical and analytical signs of infection and several walled-off necroses, one retrogastric (short arrows) on which it was decided to perform transgastric drainage. We can see the access to the collection via the stomach—lumen indicated with asterisks—and, in the later follow-up sagittal MRI reconstruction (in this case the gastric lumen is opacified with oral contrast), how the collection around the end of the tube has resolved (short arrow).

The 2012 review of the AC proposes terminology that is currently more widely accepted to refer to AP. The parameters that predict its severity are the development and duration of organ failure and the appearance of complications. CT is the technique of choice for assessing local complication, and various radiological indices have been described as additional predictors of severity, although the current consensus does not grant them the central role allotted to clinical data. For some years, the trend in the AP management has been towards less and less invasive procedures, meaning that cases where FNAB or surgical intervention are performed are now the exception. Infection is assumed where there are suggestive clinical and/or radiological signs, and radiology-guided drainage, together with endoscopic drainage, is now the technique of choice in the approach to collections. The benefits of performing this before 4 weeks of evolution are currently being investigated.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: CMOM.

- 2.

Study conception: CMOM.

- 3.

Study design: CMOM.

- 4.

Data collection: CMOM, ELGB, JROM, EPDA, JALC.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: CMOM, ELGB, JROM, EPDA, JALC.

- 6.

Statistical processing: N/A

- 7.

Literature search: CMOM, JROM.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: CMOM, ELGB, JROM.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: ELGB, JROM.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: CMOM, ELGB, JROM, EPDA, JALC.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Our thanks go to those who, together with the authors, contributed to the completion of this work, especially to Dr José María García Santos for participating in the critical review of the manuscript and encouraging us, now and always, to publish.

Please cite this article as: Ortiz Morales CM, Girela Baena EL, Olalla Muñoz JR, Parlorio de Andrés E, López Corbalán JA. Radiología de la pancreatitis aguda hoy: clasificación de Atlanta y papel actual de la imagen en su diagnóstico y tratamiento. Radiología. 2019;61:453–466.