Supplement "Advances in Musculoskeletal Radiology"

More infoMyxoid liposarcoma is classified in the group of sarcomas with adipose differentiation, which is the second most common group of sarcomas. However, myxoid liposarcoma is not a homogeneous entity, because the behavior and clinical course of these tumours can vary widely. This study aimed to describe the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features of myxoid liposarcomas and to determine whether the MRI features are associated with the histologic grade and can differentiate between low-grade and high-grade tumours and thus help in clinical decision making.

Material and methodsWe studied 36 patients with myxoid liposarcomas treated at our centre between 2010 and 2018. We analysed clinical variables (age, sex, and tumour site) and MRI features (size, depth, borders, fatty component, myxoid component, non-fatty/non-myxoid component, apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), and type of enhancement after the administration of intravenous contrast material). We correlated the MRI features with the histologic grade and the percentage of round cells.

ResultsIn our series, patients with myxoid liposarcomas were mainly young adults (median age, 43 years). There were no differences between sexes; 97.2% were located in the lower limbs, 86.1% were deep, and 77.8% had well-defined borders. Of the 23 myxoid liposarcomas that contained no fat, 16 (69.6%) were high grade (p = 0.01). All the tumors with a myxoid component of less than 25% were high grade (p = 0.01); 83.3% of those with a non-fatty/non-myxoid component greater than 50% were high grade (p = 0.03) and 61.5% had more than 5% round cells (p = 0.01). Diffusion sequences were obtained in 14 of the 36 patients; ADC values were high (median, 2 × 10−3 mm2/s), although there were no significant associations between low-grade and high-grade tumours. Contrast-enhanced images were available for 30 (83.3%) patients; 83.3% of the tumours with heterogeneous enhancement were high grade (p = 0.01).

ConclusionsMRI can be useful for differentiating between high- and low-grade myxoid liposarcomas and can help in clinical decision making.

El liposarcoma mixoide se encuadra dentro del grupo de sarcomas con diferenciación adiposa, constituyendo el segundo grupo en frecuencia de todos los tipos de liposarcomas, si bien no es una entidad homogénea, ya que dentro de los liposarcomas mixoides nos encontramos con tumores de comportamiento y evolución clínica muy diferentes. Los objetivos del estudio son describir las características por RM de los liposarcomas mixoides y determinar si existe asociación entre los datos analizados por RM con el grado histológico que permita diferenciar los tumores de bajo y alto grado ayudando en la toma de decisiones.

Material y métodosSe incluyeron 36 pacientes tratados en nuestro centro de liposarcoma mixoide entre los años 2010 y 2018. Por un lado, se analizaron variables clínicas: edad, sexo y localización, y por otro se valoraron características por RM: tamaño, profundidad, contornos, componente graso, componente mixoide, componente no graso-no mixoide, valor del coeficiente de difusión aparente y tipo de realce tras la administración de contraste intravenoso. Las variables analizadas por RM se correlacionaron con el grado histológico y el porcentaje de células redondas.

ResultadosEn nuestra serie, los liposarcomas mixoides afectan principalmente a adultos jóvenes (mediana de edad 43 años), sin diferencias significativas según el sexo, el 97,2% ubicados en miembros inferiores, el 86,1% de localización profunda y el 77,8% con contornos bien delimitados. El 69,6% (16 de 23) de los liposarcomas mixoides que no contenían grasa fueron de alto grado (p = 0,01). Todos los tumores con componente mixoide inferior al 25% fueron lesiones de alto grado (p = 0,01). El 83,3% de los tumores con componente no graso-no mixoide superior al 50% fueron de alto grado (p = 0,03). Igualmente, el 61,5% de los tumores con un componente no graso-no mixoide superior al 50% presentaron un porcentaje de células redondas de más del 5% (p = 0,01). Disponíamos secuencias de difusión en 14 de los 36 pacientes, obteniendo valores de coeficiente de difusión aparente altos (mediana de 2 × 10-3 mm2/s), aunque no hubo asociación estadísticamente significativa entre los tumores de bajo-alto grado. Treinta de los 36 pacientes incluidos en el estudio disponían de series con contraste intravenoso, de los cuales el 83,3% de los que presentaron realce heterogéneo fueron de alto grado (p = 0,01).

ConclusionesLa RM puede ser una herramienta diagnóstica útil para diferenciar entre liposarcomas mixoides de alto-bajo grado y ayudar en la toma de decisiones clínicas.

One in every 20,000 people in Spain are affected by soft tissue sarcoma. This means there are approximately 2300 cases a year. Although this group of cancers only represents 1% of the total, they cause 2% of all cancer-related deaths. In the 2013 edition of the World Health Organisation (WHO) classification of soft tissue tumours, liposarcomas come under the group known as mesenchymal tumours with adipose differentiation.1,2 Liposarcomas are one of the most common sarcomas in adults and several subtypes have been described: atypical/well-differentiated; dedifferentiated; myxoid; and pleomorphic. Myxoid liposarcomas (MLS) make up 30% of all liposarcomas, are the second most common after the atypical/well-differentiated subtype and account for approximately 5–10% of all soft tissue sarcomas in adults,3–5 which translates as a rough average of 162 cases per year in Spain.

Epidemiologically, MLS affect young adults, with a peak incidence between the ages of 30 and 50, and although rare, it is the most common variant of liposarcoma in children and adolescents. The incidence is similar in males and females. MLS most commonly develop in the depth of the soft tissues in the limbs, with over two thirds found in the thigh, while it is rarer in the retroperitoneum or subcutaneous cellular tissue. Clinically, they present as a large painless mass deep in a limb. A third of patients develop metastasis. Unlike other liposarcomas, MLS tend to metastasise to uncommon soft tissue sites (retroperitoneum, opposite limb, axilla) or bone (mainly the spine) even before it spreads to the lung.6

From a genetic point of view, MLS are characterised by the presence of the translocation t (12;16) (q3; p11), which leads to the fusion gene FUS-DDIT3, found in more than 95% of cases. In the other 5% of cases, the t (12;22) (q13; q12) variant is present, which fuses DDIT3 (also known as CHOP) with EWSR1, a gene closely related with FUS.2

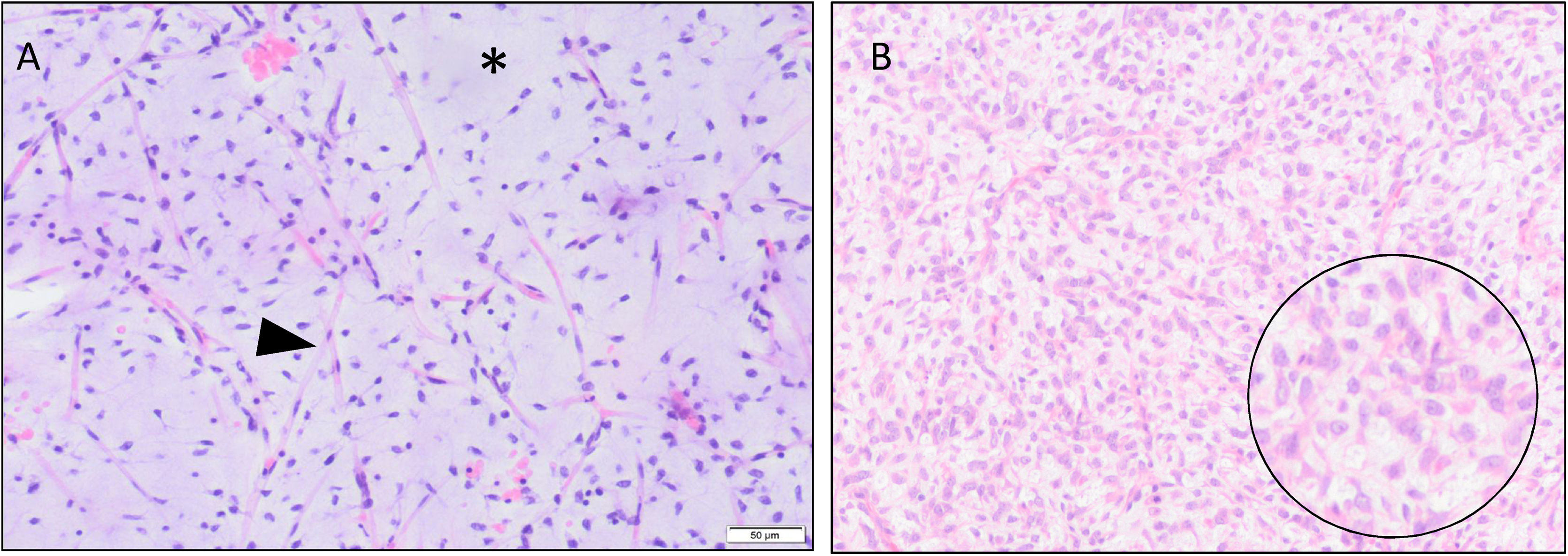

Histologically, they consist of a continuous spectrum of lesions that range from low-grade forms (predominantly myxoid) to other high-grade forms, which are poorly differentiated and have a round cell component greater than 5% (Fig. 1). This 5% is very important from a prognostic point of view. While the purely myxoid MLS are slow-growing tumours with a low risk of developing metastasis and a high survival rate (close to 70%), MLS with over 5% of round cells are considered high-grade, with a higher risk of recurrence and developing metastases, and a survival rate that can be as low as 20%.4,7,8

Histological sections (H&E) are shown that include the pathological spectrum of this type of tumour. A shows a low-grade myxoid liposarcoma (MLS), made up of spindle cells with a marked plexiform capillary network (arrowhead) and abundant myxoid stroma (*). In B, a high-grade MLS, made up of round and ovoid cells (enlargement in circle) with a considerable underlying plexiform capillary network.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging technique of choice in the investigation of MLS. Although the appearance on MRI can be highly variable, MLS do show certain features according to their histology. Purely myxoid liposarcomas tend to have a high water content and therefore low signal intensity in T1-weighted sequences and marked hyperintensity in T2-weighted sequences, to the point that they can be confused with cystic lesions. They may have some foci of adipose tissue within the tumour, although generally less than 10% of the total, and show variable enhancement after gadolinium administration. Other features described are polylobulated borders, increased perilesion T2 signal and the existence of internal septa.7 MLS with high round cell content have a more heterogeneous, non-specific appearance, indistinguishable from other high-grade soft tissue sarcomas.

The treatment of choice for MLS is surgical resection with or without prior neoadjuvant therapy (radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy). Neoadjuvant therapy is usually reserved for patients with high-risk MLS; in other words, those with a high histological grade, deep location and larger than 5 cm in size.9–11

The aim of this study was to describe the characteristics of the MLS diagnosed at our centre and try to identify any association between the data analysed by MRI and histological grade.

Material and methodsIn this retrospective descriptive research study, we carried out an analysis of all cases of MLS treated at our centre from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2018, taking as a database the information provided by the pathology department registry. This review was approved by the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research at our hospital. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Patients ≥18 years old | Patients <18 years old |

| MLS diagnosed and treated at our centre | MLS diagnosed and/or treated at other centres |

| Histological confirmation performed at our centre | MLS without histological confirmation |

| Have an initial MRI prior to any treatment | Initial MRI prior to any treatment not available, poor quality or lacking sequences for analysis |

MLS: myxoid liposarcoma.

The patients’ demographic variables were obtained from their digital medical records. In total, 49 patients diagnosed with MLS were initially included. After applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 13 cases were ruled out to leave a final sample of 36 patients.

Histological studyWe recorded the histological characteristics from the reports of the initial biopsy and/or surgical specimen, which had not been subject to neoadjuvant therapy, performed by the sarcoma specialist pathologists at our hospital. These reports are kept in the digital medical records and follow the FNCLCC (Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre Le Cancer) histological grading system,12 quantifying the presence of round cells (expressed as a percentage). Grade 1 MLS were considered low-grade and grades 2–3 high-grade. In all except one patient, who had an excisional biopsy, a percutaneous core needle biopsy (CNB) was performed prior to any treatment. Only two of the CNBs were performed by radiologists, with the majority (91.7%; 33 out of 36) performed by traumatologists.

Analysis of the MRIThe MRI images were obtained from our hospital's medical image storage system (PACS) and analysed by a radiologist with 10 years of experience in musculoskeletal pathology who had no knowledge of the histopathological grade or the percentage of round cells in the MLS cases selected for this study.

The MRI protocols were highly variable as they were from different centres and different equipment. Some 25% of the studies were performed at our centre, with 1.5 T or 3 T scanners (Philips Healthcare, The Netherlands). The baseline protocol we use for the study of soft tissue space-occupying lesions includes: axial T1-weighted TSE with and without fat suppression and T2-weighted TSE; T2-weighted TSE sequence with fat suppression parallel to the long axis of the lesion (sagittal or coronal); and single-shot echo-planar (SS-EPI) diffusion sequence in the axial plane (with three values b0, 400 and 1000 s/mm2). After administration of contrast (gadoterate meglumine 0.1 mmol/kg, Dotarem® Guerbet, France), we perform a fat-suppressed T1-weighted 3D dynamic gradient-recalled echo (GRE) sequence lasting approximately 3 min. That is followed by axial contrast-enhanced sequences and T1-weighted TSE sequences on the long-axis of the lesion with and without fat suppression. The acquisition parameters have been adapted based on the location of the lesion, size, type of antenna used and software updates over the years. The remaining 75% of the MRI scans came from other centres unconnected to our hospital. Nonetheless, all the protocols, regardless of where they were from, had T1-weighted sequences, fluid-sensitive (T2-weighted) sequences and fat-suppressed sequences. Out of all the MRI scans, we had diffusion-weighted sequences with apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps in 14 of the 36 cases. Contrast was administered in all except six patients (all six from outside centres). If several MRI studies were available, we collected the information from the MRI closest to the start of treatment, whether surgical or neoadjuvant.

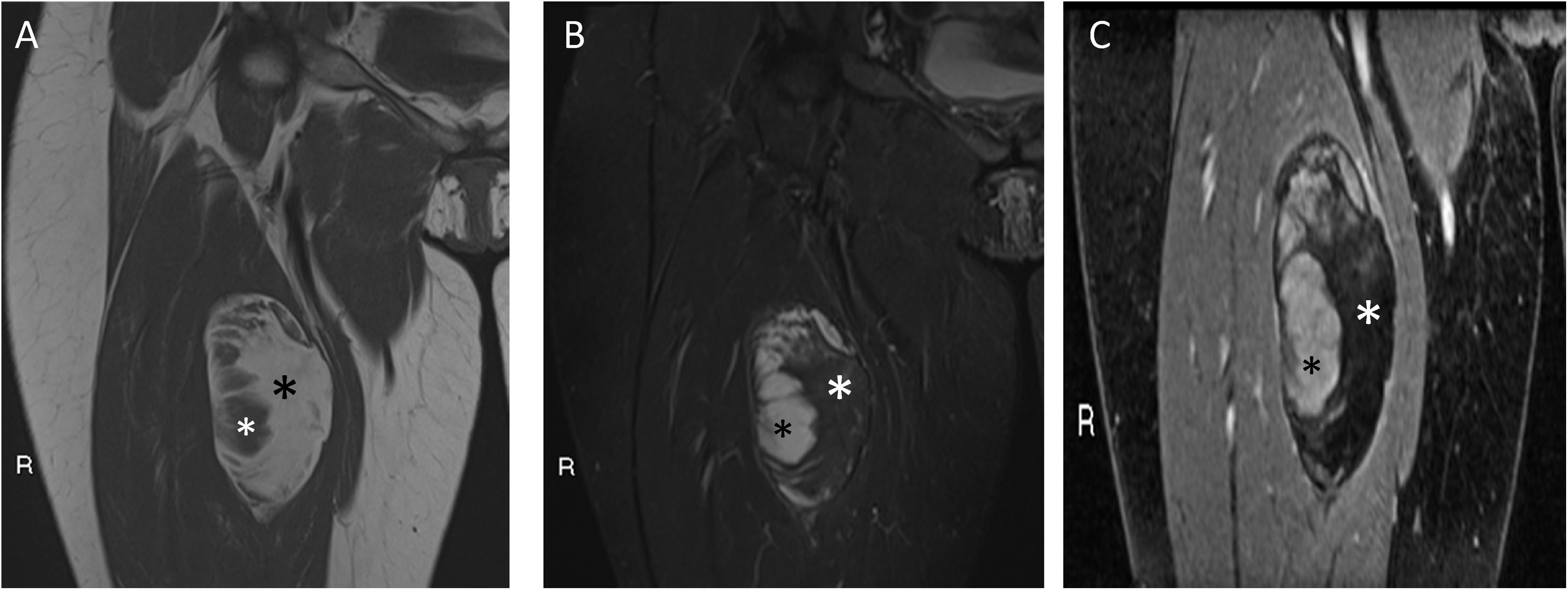

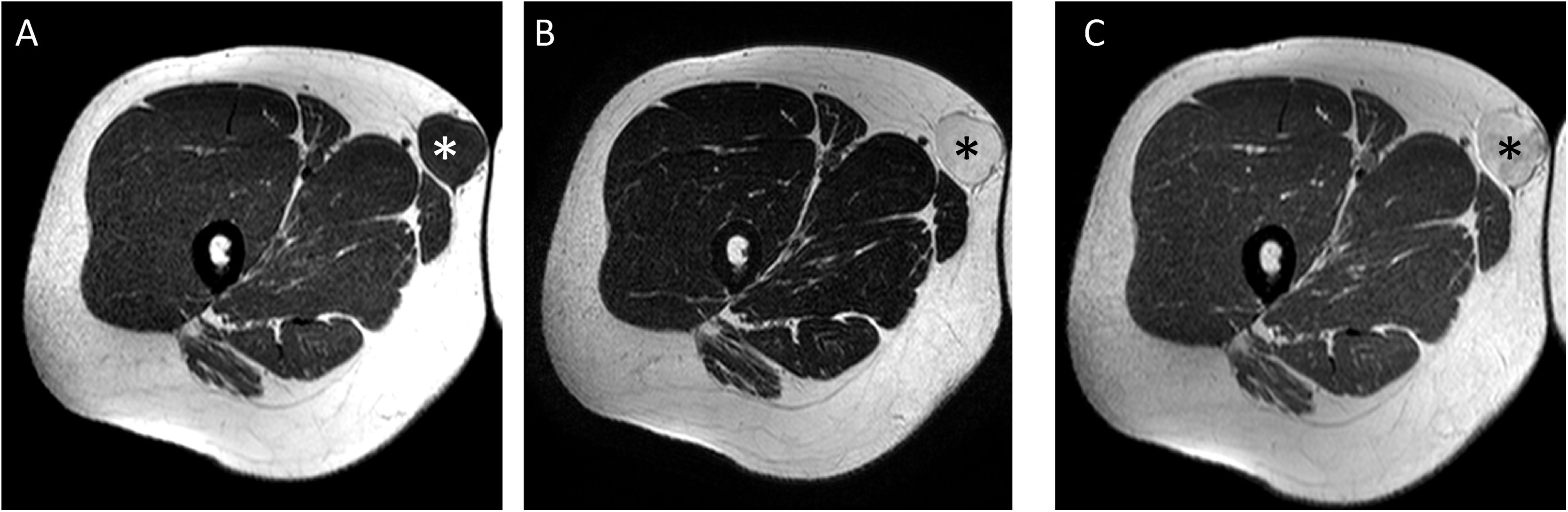

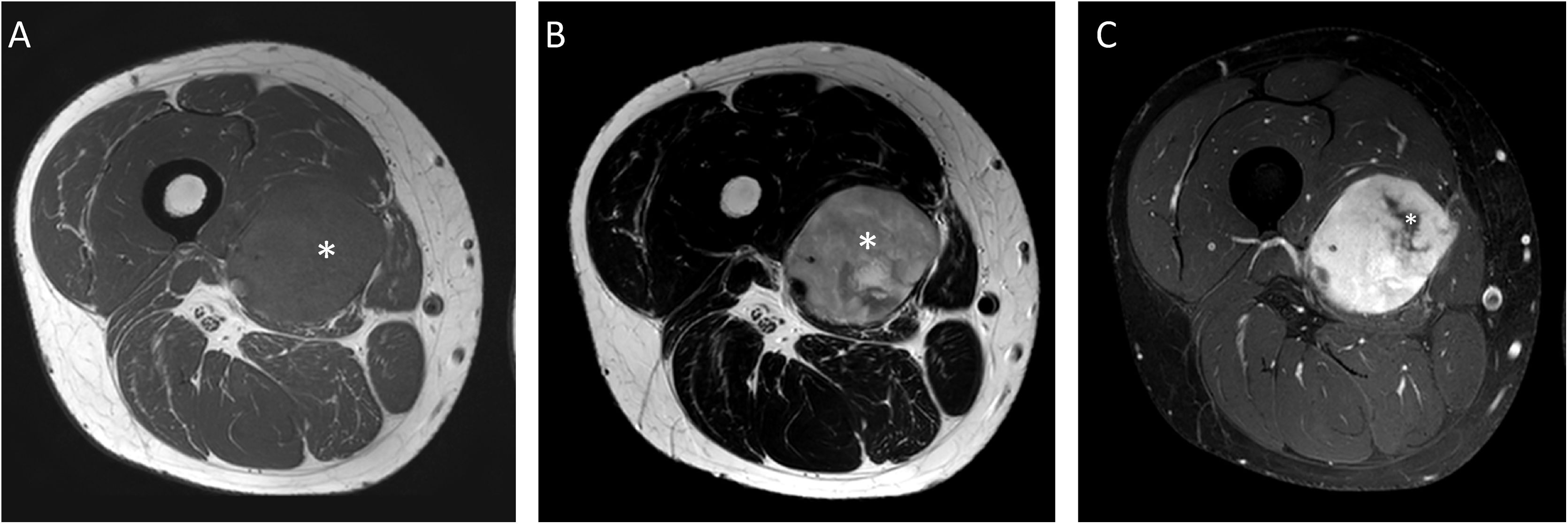

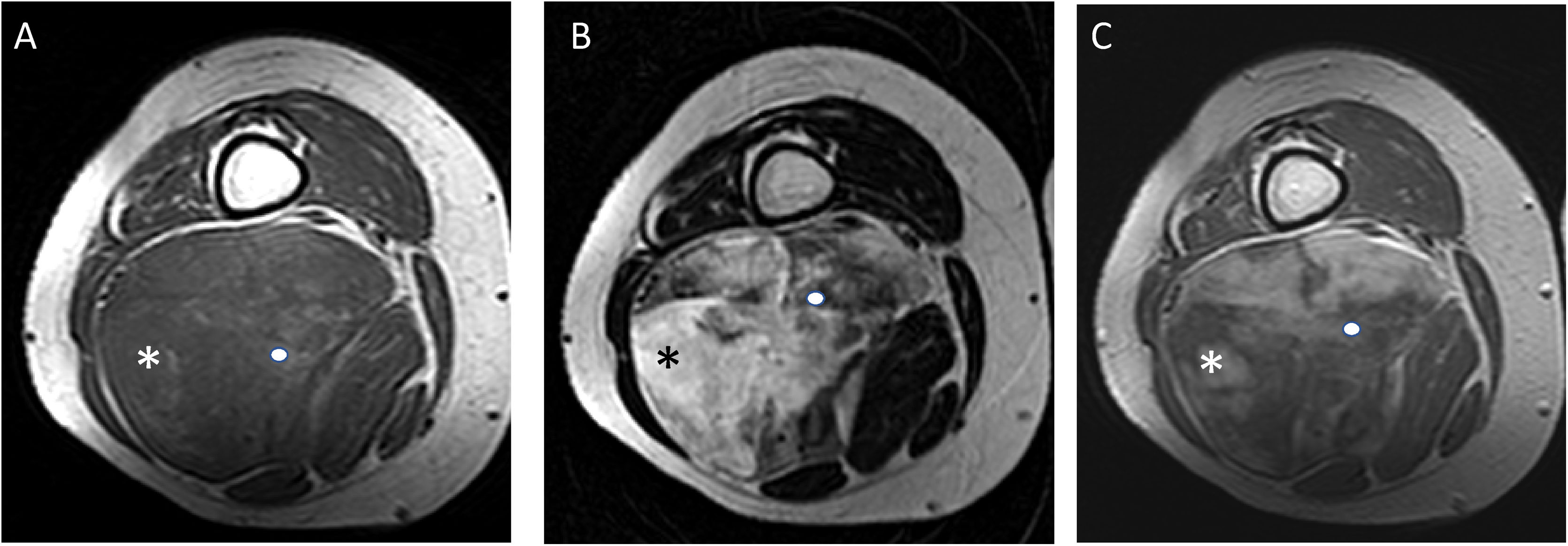

We studied the following variables: size (maximum diameter measured in millimetres, obtained in any of the planes of the MRI); location of the lesion (upper limb, lower limb or trunk); tumour depth (superficial or deep to the muscle fascia); margins (well defined/encapsulated, intermediate definition/not encapsulated, poorly defined). Based on visual estimation, a qualitative assessment was made of the signal characteristics of the tumour overall, divided into five groups (0%, <25%, 25−50%, 50−75%, >75%) of the fat component (defined as hyperintense tissue on T1-weighted sequences, which is suppressed on sequences with fat suppression and does not show enhancement after contrast administration) (Fig. 2); myxoid component (defined as hypointense tissue on T1 and very hyperintense on T2 [similar to fluid] with different degrees of enhancement after contrast administration) (Fig. 3); non-fat/non-myxoid component (defined as hypointense tissue on T1, high/intermediate signal intensity on T2 [less than fluid] and different degree of enhancement) (Fig. 4). In the studies that had diffusion sequences (14 out of 36), the ADC value was analysed (using the mean value encompassing the entire tumour in the area of interest) (Fig. 5). The studies which had contrast (30 out of 36) were classified according to the type of enhancement as: uniform (more than 75% of the tumour enhances homogeneously); and heterogeneous (the enhancement is incomplete, making up less than 75% of the total).

A 30-year-old female patient with myxoid liposarcoma (MLS) in the anterior compartment of the right thigh. Coronal T1 (A), T2 fat-suppressed (B), and T1 fat-suppressed gadolinium-enhanced (C) sequences are shown. A tumour can be seen with well-defined borders, with a fat component (black asterisk in A and white in B and C) of 50% to 75% (hyperintense in T1, with loss of signal in sequences with fat suppression and without enhancement after gadolinium administration). At the external margin of the tumour, a myxoid component can be seen (white asterisk in A and black in B and C) of 25% to 50%, with signal intensity similar to fluid in sequences without contrast and enhancement after administration of gadolinium. Low-grade 0% round-cell MLS.

A 28-year-old male patient with superficial myxoid liposarcoma (MLS) in subcutaneous cellular tissue on medial aspect of the root of the right thigh. Axial T1 (A), T2 (B) and T1 sequences after gadolinium administration (C) are shown. A tumour with well-defined borders can be seen (white asterisk in A and black in B and C) with a myxoid component greater than 75% (signal intensity similar to fluid in non-contrast sequences, hypointense in T1, markedly hyperintense in T2 and with uniform enhancement after contrast administration). MLS with high myxoid content can mimic a cystic lesion. For any lesion with an “apparently cystic” appearance in sequences without contrast with an unusual location for a synovial/ganglion cyst, the administration of contrast is necessary or, failing that, ultrasound study. In our case, the lesion showed intense uniform enhancement after gadolinium administration, confirming its solid nature.

A 30-year-old male patient with myxoid liposarcoma (MLS) in the medial compartment of the right thigh. Axial T1 (A), T2 (B) and T1 fat-suppressed sequences after gadolinium administration (C) are shown. A non-fat-non-myxoid component greater than 75% can be seen (white asterisk in A and B) [hypointense in T1, intermediate intensity in T2 sequences and heterogeneous enhancement with foci with no uptake in the medial margin of the lesion (white asterisk in C)]. High-grade MLS with 90% round-cells.

A 44-year-old male patient with myxoid liposarcoma (MLS) in the anterior compartment of the right leg (black asterisk in A, B and D, white in C). Magnetic resonance imaging from an outside centre with axial T2 sequences (A), diffusion study with three values of b 0, 400, 1000, of which we show the value b = 1000 (B), ADC map (C) and T1 with fat suppression after gadolinium administration (D). A lesion with a non-fat-non-myxoid component greater than 75% (intermediate intensity in T2-weighted sequences) can be seen, with a mean ADC value of 1.1 × 10−3 mm2/s (ROI marked in white) and heterogeneous enhancement with necrotic central area (black asterisk); these findings suggest high cellularity for this type of myxoid tumour. High-grade MLS with 100% round-cells.

All qualitative and quantitative variables were analysed. Student's t-test was used for independent samples to study the relationship between size and ADC value with histological grade (FNCLCC high/low grade) and percentage of round cells. The χ2 test and non-asymptotic methods were used to assess the association between tumour margins and tissue characteristics (fat component, myxoid component, non-fat/non-myxoid component and enhancement) with histological grade (FNCLCC high/low grade) and percentage of round cells. The analysis was performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics software for Windows, v. 25.0. Associations were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

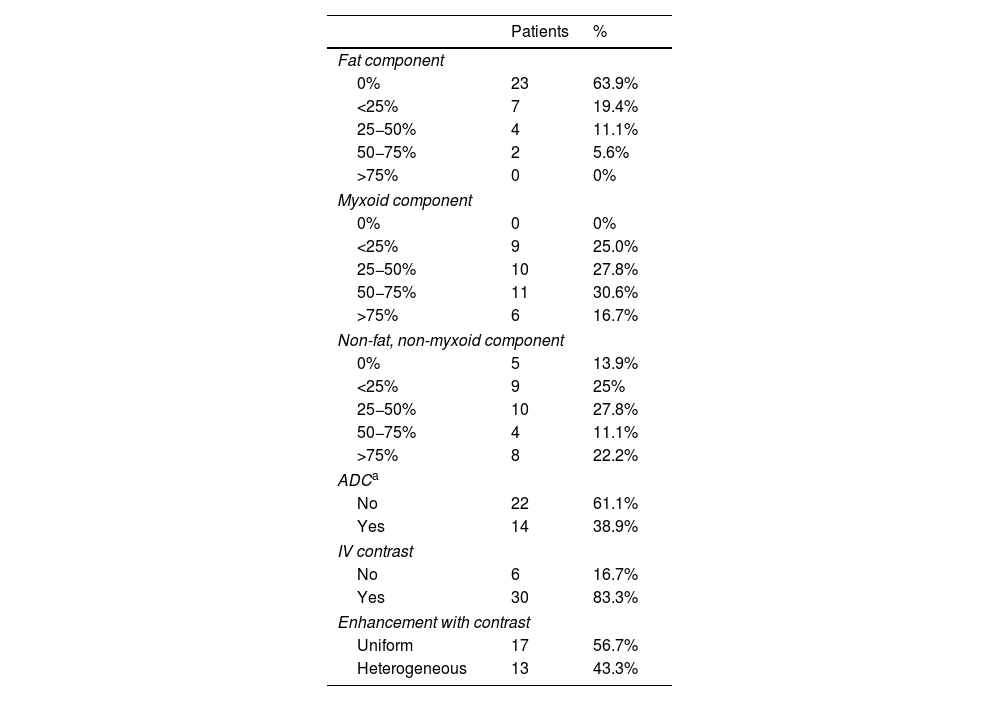

ResultsDescriptive analysisA total of 36 patients were studied, 20 male and 16 female, 19 of whom had neoadjuvant therapy prior to surgery; in 78.9% (n = 15) a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy; in 10.5% (n = 2) chemotherapy only; and in 10.5% (n = 2) radiotherapy only. Two patients refused, but all the other patients had surgery. The median age was 43 years; the youngest patient was 24 and the oldest 82. In 97.2% (n = 35) the tumour was in a lower limb; only one patient had a tumour in an upper limb. The median size of the tumour was 107 mm; the smallest was 34 mm and the largest 250 mm. In 86.1% (n = 31) the tumour was located deep to the fascia and in 13.9% (n = 5) superficial to the fascia. In total, 77.8% (n = 28) had well defined borders, 16.7% (n = 6) intermediate definition and in 5.6% (n̴1 = 2) the borders were poorly defined. The tissue characteristics revealed by MRI are shown in Table 2.

Tissue variables analysed by magnetic resonance imaging.

| Patients | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Fat component | ||

| 0% | 23 | 63.9% |

| <25% | 7 | 19.4% |

| 25−50% | 4 | 11.1% |

| 50−75% | 2 | 5.6% |

| >75% | 0 | 0% |

| Myxoid component | ||

| 0% | 0 | 0% |

| <25% | 9 | 25.0% |

| 25−50% | 10 | 27.8% |

| 50−75% | 11 | 30.6% |

| >75% | 6 | 16.7% |

| Non-fat, non-myxoid component | ||

| 0% | 5 | 13.9% |

| <25% | 9 | 25% |

| 25−50% | 10 | 27.8% |

| 50−75% | 4 | 11.1% |

| >75% | 8 | 22.2% |

| ADCa | ||

| No | 22 | 61.1% |

| Yes | 14 | 38.9% |

| IV contrast | ||

| No | 6 | 16.7% |

| Yes | 30 | 83.3% |

| Enhancement with contrast | ||

| Uniform | 17 | 56.7% |

| Heterogeneous | 13 | 43.3% |

The noteworthy data were: 63.9% (n = 23) of the tumours showed no fat signal and none of the cases had a fat component greater than 75%; 75% (n = 27) of the tumours had a myxoid component of 25% or greater (Fig. 6); and 33.3% (n = 12) had a non-fat/non-myxoid component greater than 50%. We only had diffusion sequences in 14 of the 36 patients, obtaining ADC values that ranged from 1.1 to 2.5 × 10−3 s/mm2, with a median of 2 × 10−3 s/mm2.

A 54-year-old male patient with myxoid liposarcoma (MLS) in the posterior compartment of the left thigh. Axial T2-weighted (A), fat-suppressed T1-weighted (B) and fat-suppressed T1-weighted sequences after gadolinium administration (C) are shown. A main non-fat-non-myxoid component (asterisk) can be seen with intermediate intensity on T2-weighted sequences and a myxoid component at the inner margin of the lesion with high signal similar to fluid on T2-weighted images (arrowhead). After gadolinium administration, heterogeneous enhancement is seen. High-grade MLS with 25% round-cells.

All the tumours studied with contrast (30 of the 36) showed uptake to a variable degree, with uniform enhancement in 56.7% (>75% tumour uptake).

In total, 55.6% (n = 20) of the tumours were diagnosed as high-grade MLS, while 44.4% (n = 16) were low-grade MLS. Histology analysis showed round cells in 44.4% (n = 16), with values ranging from 2% to 100%. Of the initial biopsies performed, 22.2% (n = 8) did not provide full information on histological grade or the percentage of round cells. All these patients had surgery as first-line without prior neoadjuvant therapy. Five of these eight patients were finally diagnosed from the surgical specimen as having high-grade tumours.

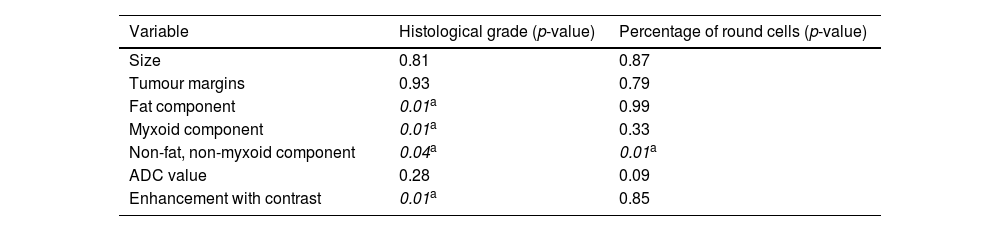

Inferential analysisThe degree of statistical significance of the association between the variables analysed by MRI and the histological variables is shown in Table 3.

Degree of statistical significance of the variables analysed.

| Variable | Histological grade (p-value) | Percentage of round cells (p-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Size | 0.81 | 0.87 |

| Tumour margins | 0.93 | 0.79 |

| Fat component | 0.01a | 0.99 |

| Myxoid component | 0.01a | 0.33 |

| Non-fat, non-myxoid component | 0.04a | 0.01a |

| ADC value | 0.28 | 0.09 |

| Enhancement with contrast | 0.01a | 0.85 |

ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient.

We found no significant differences between tumour size and margins and high- and low-grade tumours (p = 0.81 and p = 0.93, respectively).

We did find statistical significance (p = 0.01) between the fat component and the histological grade; 69.6% (n = 16) of the tumours with no fat on MRI were high-grade. In contrast, the presence of fat on MRI is suggestive of a low-grade lesion; the greater the presence of fat detected on MRI, the greater the likelihood of a low-grade tumour (none of the tumours with a fat fraction greater than 50% was high-grade).

Patients who had a myxoid tissue fraction less than 25% (n = 9) had high-grade lesions, with statistical significance found between the myxoid component and histological grade (p = 0.01).

Patients with a non-myxoid/non-fat component greater than 75% (n = 8) had high-grade lesions, with a statistically significant association between the non-myxoid/non-fat component and histological grade (p = 0.04). With the available data, a statistically significant association was also found between the non-fat/non-myxoid component and the percentage of round cells (p = 0.01). In other words, the presence of a non-fat/non-myxoid component greater than 50% entails a seven-fold greater risk of it being a high-grade tumour and a four-fold greater risk of the round cell content being above 5%. However, the 95% confidence intervals for these statistics are too wide due to the small sample size in these subgroups.

In our sample, we found no statistically significant association between ADC values and histological grade.

However, 83.3% of tumours with heterogeneous enhancement were high-grade, while 64.7% of tumours with uniform enhancement were low-grade, with a statistically significant association between the type of enhancement and histological grade (p = 0.01).

DiscussionThis study demonstrates the utility of MRI as a diagnostic technique enabling us to differentiate between high- and low-grade MLS, to complement the information obtained in the biopsy. This is particularly important as biopsies can underestimate the cancer grade by not including the zone of highest grade in the sample. With the added information from the MRI, performing a further biopsy or modifying some aspect of the neoadjuvant therapy may be considered.12,13

In terms of the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of MLS, our results are consistent with those reported in the scientific literature.2,6 It is a disease that affects young adults, located deep, with well-defined margins, mainly in the lower limbs, and there are no significant differences between the genders.

Although an association between tumour size and histological grade has already been published, we did not find statistically significant differences in our series.7,14

Although MLS are included in the group of sarcomas with adipose differentiation, they do not usually show visible fat on imaging tests. In our series, similar to that reported in the literature,14 63.9% did not show fat signal intensity. When it does appear, it is usually in the form of faint linear or amorphous foci.15 In our series, none of the cases had a fat component greater than 75% and only two cases had over 50%. While the presence of fat detectable by MRI can occur in low- and high-grade tumours, the detection of fat tends to indicate a low-grade lesion;7,14 in our series; the two cases with a fat component greater than 50% were low-grade, and 69.6% of the MLS of patients with no evidence of fat were high-grade (p = 0.01).

The myxoid component is another characteristic element of the MLS tumour matrix; the lower the purely myxoid content, the higher the likelihood of it being a high-grade MLS. In our series, all the patients with a myxoid component of less than 25% had high-grade tumours (p = 0.01), as also reported by Löwenthal et al.14

There is also a third component described in MLS comprising tissue without fat signal or purely myxoid characteristics, which is usually associated with the round cell component and therefore with high-grade tumours.14 In our study, all the patients with a non-fat/non-myxoid component greater than 75% were high-grade (p = 0.04).

As Carrascoso Arranz et al. reported,16 being tumours with myxoid matrix and high mucin and water content, they have high ADC values (median of 2 × 10−3 mm2/s), although we did not find a statistically significant association between the ADC values and histological grade.

MLS with high myxoid content can mimic "cystic" lesions on fluid-sensitive sequences. Therefore, in order to avoid under-diagnosis, it is essential to perform series after gadolinium administration. There is still a lack of consensus when it comes to classifying the different MLS uptake patterns. A retrospective study by Tateishi et al13, which included 36 patients with MLS, describes enhancement based on its extension (absent, weak or intense) and pattern (globular-nodular and diffuse). The Gimber et al. study7 of 31 patients with MLS refers to the percentage of tumour enhancement (none, <25%, 25–75% and >75%). Mi-Sook et al. describe three patterns in their article15: homogeneous (total enhancement); heterogeneous (partial enhancement); and no enhancement. In the Tateishi et al. study, intense enhancement was the most significant adverse prognostic factor and correlated with the round-cell content in the histological samples. In our series, 83.3% of patients with heterogeneous enhancement were high-grade (p = 0.01), and 64.7% of patients with uniform enhancement were low-grade. One possible explanation for this finding in our series could be that heterogeneous enhancement corresponds to a greater component of necrosis, more characteristic of high-grade lesions according to the FNCLCC grading system, while tumours with uniform and homogeneous enhancement lack necrosis, which is more typical of low-grade MLS.

The management of patients diagnosed with MLS requires a multidisciplinary approach. Although surgery is the treatment of choice in patients with localised disease, in certain circumstances they may benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy.4 However, before starting treatment, it is necessary to consider a series of factors, such as the patient's comorbidity, location, size and relationship of the tumour to adjacent structures, and of particular importance, histological grade and percentage of round cells. As already mentioned, MLS is far from being a homogeneous entity and CNB samples do not always provide all the necessary information on the histological grade and the percentage of round cells.17 In this situation, the information provided by MRI can help with decision making. In our study, 22.2% (n = 8) of the initial biopsies did not provide full information on the histological grade or the percentage of round cells. All these patients had surgery as first-line without prior neoadjuvant therapy. Five of these eight patients were diagnosed from the surgical specimen as having high-grade tumours. Reviewing the MRI images of these five patients, none had a significant fat component, two had a non-fat/non-myxoid component greater than 50% and four had heterogeneous enhancement (in one case there was no study with contrast available). In other words, these tumours showed imaging signs which, according to our results, are associated with high-grade tumours. Therefore, if the information provided by the MRI had been taken into account, neoadjuvant therapy could have been considered or the initial biopsy repeated before surgery (Fig. 7).

A 49-year-old female patient with a rapidly growing swelling on the posterior aspect of the right thigh who consulted Accident and Emergency with initially suspected haematoma in the context of muscle strain. Axial T1 (A), T2 (B) and T1 sequences without fat suppression after gadolinium administration (C) are shown. A lesion with a non-fat-non-myxoid component of more than 50% can be seen [hypointense on T1, intermediate intensity on T2 sequences and heterogeneous enhancement after gadolinium administration (asterisk)]. In this case, the mass also shows a haemorrhagic component (circle). Following the imaging findings, a core-needle biopsy (CNB) was performed with a diagnosis of round cell MLS, but without being able to specify the percentage of round cells or the histological grade. Surgical resection was performed without prior neoadjuvant therapy, with a final diagnosis of high-grade MLS in the surgical specimen. The information provided by the MRI suggested a high grade, so the option of neoadjuvant therapy or repeat CNB could have been considered for a more precise diagnosis. Six years later, the patient developed a bone metastasis of her MLS in the distal diaphyseal region of her contralateral femur (hyperintense intramedullary lesion), confirmed by bone biopsy.

Any lesion that has an extracellular matrix with a high content of mucopolysaccharides, hyaline cartilage and necrosis can simulate a cystic lesion.15 There are many soft tissue tumours with myxoid content, so the differential diagnosis tends to consider both benign entities, such as intramuscular myxoma (difficult to differentiate from MLS, although myxomas usually have a more homogeneous enhancement and no fat content) and ganglia (tend to be in characteristic locations in relation to tendon sheaths and not intramuscular, with no enhancement or slight capsular enhancement), and malignancies, such as extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (usually a heterogeneous lobular enhancement pattern in arches-rings that reflect their cartilaginous origin).

Our study has a number of limitations. First is its retrospective nature. Secondly, like previous studies, we had a small sample size, reflecting the low incidence of this type of tumour. Associations with a borderline level of statistical significance could probably have been demonstrated with a larger sample size. Thirdly, our study only included adult patients aged 18 or over, which could lead to bias. Fourthly, the MRI studies were obtained in various centres, with non-standardised and non-homogeneous protocols and over a period of nine years, which at times complicated the process of obtaining the values analysed as it was difficult to distinguish the different tissue components. Last of all, interobserver reproducibility was not verified.

In conclusion, MRI is a useful diagnostic tool that enables us to differentiate between high- and low-grade MLS and help in clinical decision-making. The MRI features that pointed to a high-grade MLS in our sample were the absence of fat, low myxoid content, high content of non-fat/non-myxoid tissue and heterogeneous enhancement. A high fat content and uniform enhancement would suggest a low-grade MLS. Nevertheless, we think it would be of interest to carry out a prospective study using standardised MRI protocols and with a larger sample size, for which, given the low incidence of this type of tumour, the collaboration of several centres would be necessary.

Authorship- 1

Person responsible for the integrity of the study: VET.

- 2

Study conception: VET, CAG, DVP, MCM, JIR, ACR and JMP.

- 3

Study design: VET, CAG, DVP, MCM, JIR, ACR and JMP.

- 4

Data collection: VET.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: VET, CAG, DVP, MCM, JIR, ACR and JMP.

- 6

Statistical processing: VET and CAG.

- 7

Literature search: VET.

- 8

Drafting of the article: VET, CAG, DVP, MCM, JIR, ACR and JMP.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: VET, CAG, DVP, MCM, JIR, ACR and JMP.

- 10

Approval of the final version: VET, CAG, DVP, MCM, JIR, ACR and JMP.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

![A 30-year-old male patient with myxoid liposarcoma (MLS) in the medial compartment of the right thigh. Axial T1 (A), T2 (B) and T1 fat-suppressed sequences after gadolinium administration (C) are shown. A non-fat-non-myxoid component greater than 75% can be seen (white asterisk in A and B) [hypointense in T1, intermediate intensity in T2 sequences and heterogeneous enhancement with foci with no uptake in the medial margin of the lesion (white asterisk in C)]. High-grade MLS with 90% round-cells. A 30-year-old male patient with myxoid liposarcoma (MLS) in the medial compartment of the right thigh. Axial T1 (A), T2 (B) and T1 fat-suppressed sequences after gadolinium administration (C) are shown. A non-fat-non-myxoid component greater than 75% can be seen (white asterisk in A and B) [hypointense in T1, intermediate intensity in T2 sequences and heterogeneous enhancement with foci with no uptake in the medial margin of the lesion (white asterisk in C)]. High-grade MLS with 90% round-cells.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/21735107/00000065000000S2/v1_202310180534/S2173510722000349/v1_202310180534/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr4.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![A 49-year-old female patient with a rapidly growing swelling on the posterior aspect of the right thigh who consulted Accident and Emergency with initially suspected haematoma in the context of muscle strain. Axial T1 (A), T2 (B) and T1 sequences without fat suppression after gadolinium administration (C) are shown. A lesion with a non-fat-non-myxoid component of more than 50% can be seen [hypointense on T1, intermediate intensity on T2 sequences and heterogeneous enhancement after gadolinium administration (asterisk)]. In this case, the mass also shows a haemorrhagic component (circle). Following the imaging findings, a core-needle biopsy (CNB) was performed with a diagnosis of round cell MLS, but without being able to specify the percentage of round cells or the histological grade. Surgical resection was performed without prior neoadjuvant therapy, with a final diagnosis of high-grade MLS in the surgical specimen. The information provided by the MRI suggested a high grade, so the option of neoadjuvant therapy or repeat CNB could have been considered for a more precise diagnosis. Six years later, the patient developed a bone metastasis of her MLS in the distal diaphyseal region of her contralateral femur (hyperintense intramedullary lesion), confirmed by bone biopsy. A 49-year-old female patient with a rapidly growing swelling on the posterior aspect of the right thigh who consulted Accident and Emergency with initially suspected haematoma in the context of muscle strain. Axial T1 (A), T2 (B) and T1 sequences without fat suppression after gadolinium administration (C) are shown. A lesion with a non-fat-non-myxoid component of more than 50% can be seen [hypointense on T1, intermediate intensity on T2 sequences and heterogeneous enhancement after gadolinium administration (asterisk)]. In this case, the mass also shows a haemorrhagic component (circle). Following the imaging findings, a core-needle biopsy (CNB) was performed with a diagnosis of round cell MLS, but without being able to specify the percentage of round cells or the histological grade. Surgical resection was performed without prior neoadjuvant therapy, with a final diagnosis of high-grade MLS in the surgical specimen. The information provided by the MRI suggested a high grade, so the option of neoadjuvant therapy or repeat CNB could have been considered for a more precise diagnosis. Six years later, the patient developed a bone metastasis of her MLS in the distal diaphyseal region of her contralateral femur (hyperintense intramedullary lesion), confirmed by bone biopsy.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/21735107/00000065000000S2/v1_202310180534/S2173510722000349/v1_202310180534/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr7.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)