Suplement “Update and good practice in the contrast media uses”

More infoExtracellular gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCA) are commonly used in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) because they increase the detection of alterations, improve tissue characterisation and enable a more precise differential diagnosis. GBCAs are considered to be safe but they are not risk-free. When using GBCAs, it is important to be aware of the risks and to know how to react in different situations (pregnancy, breastfeeding, kidney failure) including if complications occur (extravasations, adverse, allergic or anaphylactic reactions). The article describes the characteristics of the gadolinium molecule, the differences in the biochemical structure of these GBCA, their biodistribution and the effect on the MRI signal. It also reviews safety aspects and the most common clinical applications.

Los contrastes de gadolinio (CGd) de distribución extracelular se utilizan frecuente-mente en resonancia magnética (RM) porque aumentan la detección de alteraciones, mejoran la caracterización tisular y permiten un diagnóstico diferencial más preciso.

Los CGd se consideran seguros, pero no están exentos de riesgo. Conocer los ries-gos, saber qué actitud adoptar en diferentes situaciones (embarazo, lactancia, insufi-ciencia renal) y cómo reaccionar si se producen complicaciones (extravasaciones, re-acciones adversas, alérgicas y anafilácticas) es imprescindible para el uso adecuado de los CGd.

Se presentan las características de la molécula de gadolinio, las diferencias en la es-tructura bioquímica, su biodistribución y el efecto sobre la señal de RM. Se revisan los aspectos de seguridad y las aplicaciones clínicas más frecuentes.

Extracellular gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) are useful because they increase sensitivity and specificity in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).1

In its basic form, gadolinium (Gd) is toxic, but when bound to organic ligands it forms stable complexes that serve as safe, effective contrast agents. The chemical complexes formed between Gd ions and organic molecules are called Gd chelates.2

The chemical structure of Gd chelates determines their physicochemical properties, safety profiles and frequency of adverse reactions.3,4

Although GBCAs have an excellent safety profile, they can cause acute adverse reactions.2 Safe administration of GBCAs requires an understanding of specific protocols, including fasting requirements, guidelines for use during pregnancy and lactation, and dosing considerations for patients with impaired renal function. Radiologists must understand the safety profiles of specific GBCAs to prevent potential complications and manage any adverse events that arise.5

This paper reviews the physicochemical properties, pharmacokinetics, dosages and the clinical administration of extracellular GBCAs. It also reviews their safety profiles and summarises their primary diagnostic applications.

Physicochemical characteristicsCharacteristics of gadoliniumGd is a silvery-white, malleable and ductile metal in the lanthanoid group. Its atomic number is 64 and it has strong magnetic properties.

Its magnetic properties arise from the number and arrangement of unpaired electrons in its outer shells. In its ionic form, Gd3+ is the stable ion with the most electrons in its outer shell and this determines its high level of paramagnetism.

The paramagnetic properties of Gd3+ alter the magnetic field around the molecule, enhancing the relaxation rates of the hydrogen nuclei (H1). The paramagnetic effect of Gd3+ is so strong that a single Gd3+ atom causes a shortening of the longitudinal and transverse relaxation times of many H1.

Contrast agent characteristicsIn its free form, Gd3+ is toxic, but when bound to large organic molecules it becomes an inert, non-toxic material that is suitable for use as a contrast medium. GBCAs can be linear or macrocyclic depending on their structure. They can have an ionic or non-ionic charge (Table 1).4

Extracellular gadolinium-based contrasts: biostructure, ionic charge and relaxivity in plasma at 37 °C.

| Generic name | Commercial name | Biostructure | Ionic charge | Relaxivity r11.5T (mmol−1 s−1) | Relaxivity r13T (mmol−1 s−1) | Distributed in Spain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gadodiamide | Omniscan®GE Healthcare | Linear | Non-ionic | 4.0–4.6 | 3.8–4.2 | No |

| Gadopentetate dimeglumine | Magnevist®Schering-Bayer | Linear | Ionic | 3.9–4.3 | 3.5–3.9 | No |

| Gadoversetamine | Optimark®Guerbet | Linear | Non-ionic | 4.4–5.0 | 4.2–4.8 | No |

| Gadobenic acidGadobenate dimeglumine | MultiHance®Bracco Diagnostics | Linear | Ionic | 6.0–6.6 | 5.2–5.8 | Yes |

| Gadobutrol | Gadovist®Bayer HealthCare | Macrocyclic | Non-ionic | 4.9–5.5 | 4.7–5.3 | Yes |

| Pixooscan®GE Healthcare | Macrocyclic | Non-ionic | 4.9–5.5 | 4.7–5.3 | Yes | |

| Gadobenic acid Gadoterate meglumine | Dotarem®Guerbet | Macrocyclic | Ionic | 3.4–3.8 | 3.3–3.7 | Yes |

| Clariscan®GE Healthcare | Macrocyclic | Ionic | 3.4–3.8 | 3.3–3.7 | Yes | |

| Gadoteridol | Prohance®Bracco Diagnostics | Macrocyclic | Non-ionic | 3.9–4.3 | 3.5–3.9 | Yes |

| Gadopiclenol | Vueway®Bracco Diagnostics | Macrocyclic | Non-ionic | 12.8 | 11.6 | No |

| Elucirem®Guerbet | Macrocyclic | Non-ionic | 12.8 | 11.6 | No |

Macrocyclic ionic complexes have been shown to be more stable than linear complexes and less likely to release Gd3+, which can be deposited in various tissues.

Following the indications of the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency (AEMPS) and the recommendations of the European Committee for Risk Assessment in Pharmacovigilance, linear GBCAs (Magnevist®, Optimark® and Omniscan®) have been withdrawn from the market.6,7 There is some disagreement over the recommendation to suspend all use of these linear GBCAs without taking into account the individual characteristics of each product.3

The effect of gadolinium-based contrast agents on magnetic resonance signalThe Gd3+ ion causes a shortening of the longitudinal relaxation time (T1) and the transverse relaxation time (T2).

The T1 shortening of protons adjacent to the Gd3+ molecule is what causes the increased signal in T1-weighted sequences. Thus, the visible hyperintensity is not the Gd3+, but rather its effect on the adjacent H1.

T2 shortening causes decreased intensity in T2-weighted sequences.

The predominant effect of Gd3+ on longitudinal or transverse relaxation is related to its concentration. Thus, at low concentrations, T1 shortening predominates and causes hyperintensity in T1-weighted sequences; while at high concentrations, T2 shortening predominates, causing low signal intensity in T2-weighted sequences.

Relaxitivity is a key property of GBCAs, indicating their ‘enhancement power’ as contrast agents. This physical constant is influenced by the molecular structure of the agent, which determines the number of water molecules it interacts with, as well as the kinetics of the compound. It reflects the contrast agent’s ability to modify the relaxation times of nearby H1. The units of measurement for relaxivity are r1 and r2, and they are expressed in mmol−1 s−1 (Table 1).3,8–10

Recent studies have revealed physical, chemical, and pharmacokinetic properties of gadopiclenol, a new macrocyclic molecule10 which boasts high relaxivity. This agent has been accepted by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and it received approval from the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) during their meeting in October 2023.11

Pharmacokinetics/biodistributionExtracellular GBCAs are hydrophilic and do not bind to proteins or receptors. They are usually administered intravenously. Initially, they are distributed in the intravascular space and, because of their low molecular weight, they quickly pass into the interstitial space through the capillaries. They do not cross the blood-brain barrier or intact cell membranes and are eliminated unmetabolised via the urinary tract by glomerular filtration.1

The half-life of a GBCA describes the time it takes for the concentration of a contrast to be reduced by half. This takes around 90 min in healthy patients, with more than 95% of the GBCA usually having been eliminated in under 24 h.4 In patients with moderately impaired renal function, the half-life is prolonged to around six hours, while it is prolonged to around nine hours in patients with severe impairment, and up to 30 h for patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of <5 ml/min or those on dialysis.4 The rapid elimination phase is followed by a slower clearance of residual nanomolar traces that are unevenly distributed in the tissues. It is well established that GBCAs are not completely excreted in urine; residual gadolinium has been detected primarily in the bone, liver, and brain, suggesting the presence of an extracellular interstitial compartment where gadolinium can be retained for extended periods.3

SafetyFastingFasting is not required prior to GBCA administration.

The need for fasting prior to the intravenous (IV) administration of contrast agents was common when hyperosmolar iodinated contrast agents were used and many patients vomited; therefore, fasting was advised to avoid possible aspiration.2,12 However, GBCAs and hypo- and isomolar non-ionic iodinated contrasts pose very low risks of nausea, vomiting or aspiration, and fasting prior to administration provides no benefits.2,12,13

ExtravasationContrast extravasation is one of the most common complications of IV injections, and is mostly limited to soft tissues adjacent to the vein, skin or subcutaneous tissue.14,15

GBCA extravasation occurs less frequently than with iodinated contrasts, probably due to the reduced volumes of GBCA administered, the slower rate of administration and the more commonly used mode of manual administration.16

Risk factors for extravasation are related to technique and patient conditions. To minimise these risks, the following recommendations are made: 1) Use angiocatheters rather than butterfly needles, 2) perform meticulous IV catheter insertion technique, 3) carefully secure an inserted catheter.2

Pregnancy and gadolinium-based contrastsSome GBCAs have been shown to cross the placental barrier in non-human primates;17 they reach the fetal circulation system and are excreted into the amniotic fluid via urine. Subsequently, a small amount of the GBCA might be swallowed and absorbed into the fetal gut and then excreted back into the amniotic fluid.

No adverse effects on fetuses have been demonstrated following the administration of GBCAs at standard clinical doses. While a retrospective study reported an increased risk of fetal or neonatal death, as well as a higher incidence of rheumatological, inflammatory and infiltrative diseases, along with skin issues in children,18 it is important to note that the study’s methodology has been challenged and remains unconfirmed. Consequently, the current recommendation is to avoid GBCAs, reserving them for situations in which they are clearly indicated in MRI and where the benefits outweigh the potential, albeit unknown, risks associated with fetal exposure.2,12,19 The European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) recommends administering macrocyclic GBCAs at the lowest possible dose only.12

Breastfeeding and gadolinium-based contrastsIt is considered safe to continue breastfeeding normally after the administration of a macrocyclic GBCA.12 However, some suggest that breastfeeding patients should be informed so they can decide whether to temporarily stop breastfeeding for a period of 12–24 h,2 given that the administration of a GBCA may change the taste of the milk and the infant may refuse to feed.

These conclusions are based on the observation that less than 0.04% of the contrast administered to the mother is excreted in breast milk in the first 24 h, with most of the Gd likely existing in a stable, chelated form.20 Less than 1% of the ingested contrast is absorbed through the infant’s gastrointestinal tract, equating to less than 0.0004% of the administered dose, which is significantly lower than the dose permitted for IV use in neonates.

Adverse reactionsGBCAs are very well tolerated. Adverse reactions may occur in 0.07–2.4% of cases, most of which are mild and physiological, such as a cold, warm or painful sensation at the injection site, headaches, paraesthesia, dizziness or nausea with or without vomiting. Allergic-type adverse reactions can occur in between 0.004 and 0.7% of cases and their manifestations are similar to those of an allergy-type reaction to an iodinated contrast medium.

Severe, life-threatening anaphylactic reactions are rare, with a reported frequency of between 0.001 and 0.01%.2 While fatal reactions are very uncommon, some cases have been reported.21

The risk of adverse reaction increases up to eight times if there has been a prior reaction to a GBCA. If the patient has had a moderate or severe allergy-type prior reaction, and an MRI with GBCA administration is considered necessary, a different contrast agent should be used to the one that caused the previous reaction. Furthermore, corticosteroid prophylaxis is advised in these cases, even though there are no studies to demonstrate that it is effective in reducing the likelihood of a new reaction.

Renal function—nephrotoxicityGBCAs are not nephrotoxic at doses approved for clinical use. The low viscosity of GBCAs and the small volumes administered minimise their potential nephrotoxicity. The risk of acute renal failure following GBCA administration is virtually non-existent in patients with normal renal function. Additionally, there is no evidence to suggest a risk of nephrotoxicity in patients with mild to moderate renal impairment.4

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosisIn 2000, the term ‘Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis’ (NSF) was introduced to describe a condition affecting patients with end-stage chronic kidney disease, particularly those undergoing dialysis. Initial symptoms typically include skin thickening and/or itching, which may progress to joint contractures and immobility over time. It mainly affects the skin and subcutaneous tissues, but can also affect the lungs, oesophagus, heart or skeletal muscles.2 The association between NSF and GBCA administration in patients with advanced kidney disease was first observed in 2006. Symptom onset following GBCA administration varies from days to months and, exceptionally, to years after the last dose.

The mechanism behind the development of NSF remains unclear, but it is thought to be associated with the release of Gd from the chelates.

After the association between GBCAs and NSF was demonstrated, guidelines were established for the appropriate use of GBCAs in patients with renal failure. Since the implementation of these guidelines, no new cases of NSF have been reported.2,12

Tables 212 and 32 classify GBCAs according to the likelihood of NSF development and set out recommendations for the use of GBCAs.

ESUR classification and recommendations on the use of GBCAs in cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.12

| Group | Generic name | Commercial name | Biostructure | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher risk | Gadodiamide | Omniscan® | Linear | The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has suspended the IV use of high-risk contrasts (Omniscan®, Magnevist®) and Optimark® has been withdrawn from the European market. |

| Gadopentetate dimeglumine | Magnevist® | Linear | ||

| Gadoversetamine | Optimark® | Linear | ||

| ||||

| Moderate risk | Gadobenic acid | MultiHance® | Linear with benzene group | The EMA approves the use of moderate-risk GBCAs (Multihance®, Primovist®) for hepatobiliary studies only. |

| Gadoxetic acid | Eovist®Primovist® | Linear with benzene group | ||

| Low risk | Gadobutrol | Gadovist® | Macrocyclic |

|

| Gadoteric acid | Dotarem® | Macrocyclic | ||

| Gadoteric acid | Clariscan® | Macrocyclic | ||

| Gadoteridol | ProHance® | Macrocyclic |

GBCA: gadolinium-based contrast agent; ESUR: European Society of Urogenital Radiology; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

ACR classification and recommendations on the use of GBCAs in cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.2

| Group | Generic name | Commercial name | Biostructure | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group IContrasts associated with the highest number of NSF cases | Gadodiamide | Omniscan® | Linear | Risk of developing NSF if: |

| Gadopentetate dimeglumine | Magnevist® | Linear | ||

| ||||

| Gadoversetamine | Optimark® | Linear | ||

| Group IIContrasts associated with few, if any, clear-cut NSF cases | Gadobenic acid | MultiHance® | Linear with benzene group | The risk of NSF with standard or lower doses of a GBCA is sufficiently low and possibly even non-existent. Therefore, assessment of renal function with a questionnaire or laboratory tests prior to the intravenous administration of a GBCA is optional. |

| Gadobutrol | Gadovist® | Macrocyclic | ||

| Gadoteric acid | Dotarem® | Macrocyclic | ||

| Gadoteric acid | Clariscan® | Macrocyclic | ||

| Gadoteridol | ProHance® | Macrocyclic | ||

| Gadopiclenol | Elucirem® | Macrocyclic | ||

| Gadopiclenol | Vueway® | Macrocyclic | ||

| Group IContrasts with limited data on NSF risk. But few, if any, cases of NSF have been reported with no ambiguous factors. | Gadoxetic acid | Eovist®Primovist® | Linear with benzene group | There are insufficient data to determine the risk of NSF following the administration of Group III GBCAs.It is important to identify patients at risk of developing NSF: |

|

ACR: American College of Radiology®; GBCA: gadolinium-based contrast agent; NSF: nephrogenic systemic fibrosis; IV: intravenous.

In 2014, areas of hypersignal were detected on T1-weighted sequences in the dentate nuclei, globus pallidus and multiple other brain locations in patients with normal renal function. There was no clinical evidence of renal or liver disease in these patients and they had been administered multiple routine doses of a GBCA. Subsequent investigations revealed that these hypersignals on T1-weighted sequences correspond to Gd deposits in their original chelate form, newly formed chelates with endogenous macromolecules, or insoluble forms of Gd. These Gd deposits have been confirmed in biopsies and necropsies of patients exposed to various GBCAs.3 Deposits occur even in the absence of clinically evident disease and in the context of an intact blood-brain barrier.2 Gd deposition has also been demonstrated in bone, kidney and liver. In bone, Gd deposition is even higher than in the nervous system and it is thought that bone may constitute a reservoir of Gd following its transmethylation with calcium. In the kidneys and liver, Gd is mainly found heterogeneously distributed in the vascular endothelium and tissue interstitium.3

In July 2015, a safety alert was issued indicating that the risk and clinical significance of these Gd deposits was under investigation.2 To date, no reports have been published to confirm that these deposits are associated with histological changes and no adverse clinical consequences are known. However, further research is warranted to clarify the mechanisms of deposition, the chelation status of these deposits, the relationship to the stability and binding affinity of the GBCAs, and their theoretical toxic potential, which may be different for different GBCAs. Until the mechanisms involved and their clinical consequences are fully understood, the safety and tissue deposition potential of GBCAs should be carefully evaluated.2

Doses and mode of administrationExtracellular GBCAs are most commonly administered intravenously, but there are other possible routes of administration such as intra-articular and, occasionally, intrathecal.

Intravenous route: the dose is generally 0.1 mmol/kg.22 It can be administered by manual embolisation if dynamic studies are not required, or by injector, which ensures the homogeneity of the embolisation when a dynamic study and analysis of contrast kinetics with enhancement curves are required. The method of administering the GBCA varies according to the pathology, the MRI equipment and the sequences used. Table 4 summarises some of the main indications.23–25

Typical administration routes, doses and flow rates of extracellular GBCAs in specific clinical indications.

| Area | Administration route | Indication | Dose | Flow rate | Saline solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS | Intravenous | Pre- and post-contrast static studies | 0.1 mmol/kg | 2 ml/s | 20 ml |

| Intravenous | T1 or T2* perfusion | 0.1–0.2 mmol/kg | 5 ml/s | 20 ml | |

| Intravenous | Contrast-enhanced MRI angiography:Malformations etc. | 0.1 mmol/kg | 2 ml/s | 20 ml | |

| Intrathecal | Intrathecal by direct (lumbar) punctureCerebrospinal fluid complex abnormalities | Less than 1.0 mmol | – | – | |

| Breast | Intravenous | DynamicBreast cancer and screening | 0.1 mmol/kg | 2 ml/s | 20 ml |

| Cardiovascular | Intravenous | First-pass perfusion | 0.05–0.1 mmol/kg | 3–7 ml/s | 30 ml |

| Intravenous | Delayed enhancement | 0.1–0.2 mmol/kg | 2–3 ml/s | 20 ml | |

| MRI Angiography | Intravenous | Aorta, pulmonary arteries and veins, renal arteries | 0.1–0.2 mmol/kg | 3–5 ml/s | 20 ml |

| Abdomen - pelvis | Intravenous | Liver, pancreas, gallbladder and bile ducts, MRI enterography, peritoneum, pelvis, prostate, scrotum | 0.1 mmol/kg | 2 ml/s | 20 ml |

| Musculoskeletal | Intravenous | Basic pre- and post-contrast.Dynamic characterisation studies | 0.1 mmol/kg | 2 ml/s | 20 ml |

| Intra-articular | Direct MRI-arthrography | Diluted GBC: 0.1 ml of GBC (0.5 mmol/ml) in 20 ml of saline solution | – | – |

CNS: Central Nervous System; GBCA: Gadolinium-based contrast agent; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

New high-relaxation contrasts (not yet commercialised) enable the dose of Gd to be reduced without lowering its efficacy.11,26 Gadopiclenol at 0.05 mmol/kg has been reported to have a safety profile and lesion detection capacity comparable to 0.1 mmol/kg of a GBCA like Gadovist®.27 Its pharmacokinetics and safety profile are the same in paediatric patients aged 2 to 17 years, as in adults.28

Intra-articular route: MRI arthrography with intra-articular GBCA administration is the reference technique for the assessment of joint structures. This is performed by administering a diluted GBCA through a joint puncture (Table 4). Proper dilution is critical because increased concentration causes decreased signal in T1- and T2-weighted sequences and possible diagnostic errors.29 The amount to inject depends on the joint, with the following being generally accepted: glenohumeral 8–15 ml, elbow 3–6 ml, radiocarpal 3–4 ml, hip 10–12 ml, knee 30–40 ml, ankle 4–8 ml, metatarsophalangeal 1–2 ml.30

Intrathecal route: This is used to detect complex cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities. Intrathecal GBCA administrations are safe at low doses, but neurotoxic manifestations have occurred in cases of accidental overdose. A recent meta-analysis found that 10 patients (out of 1036 analysed) had experienced severe neurotoxic manifestations after intrathecal GBCA administration. The analysis concluded that there is relative clinical safety with low intrathecal doses (up to 1.0 mmol) but that randomised controlled trials or prospective studies are needed to confidently define indications and doses of GBCAs.31

Clinical applications of extracellular gadolinium-based contrast agentsThe administration of GBCAs is indicated for the examination of various pathologies across different fields of radiology. Below are some key recommendations and guidelines for their use. A comprehensive analysis of all pathologies and the various sequences used with GBCAs is beyond the scope of this paper.

Central nervous systemGd-enhanced MRI is indicated for many pathologies of the central nervous system (CNS), head and neck. The most common indications include differential diagnosis and the spread of tumours (Fig. 1), metastases, infections, demyelinating diseases and suspected vascular lesions (arteriovenous malformations, aneurysms, dural fistulas).32–35 Depending on the clinical suspicion, Gd-enhanced MRI might be indicated for diagnosis, post-treatment monitoring and follow-up.34 In other cases, such as multiple sclerosis, GBCAs are initially indicated in the diagnosis and prognosis of the disease, but are now generally not considered necessary and should not be routinely used during follow-up.34

Seventeen-year-old male with an indurated and adherent lesion on the ventral side of the tongue. Post-contrast fat-suppressed T1-GRE MRI shows a nodule in the left anterior third of the tongue with heterogeneous enhancement (arrows). The pathological diagnosis was synovial sarcoma.

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; GRE: fast gradient echo.

Studies are preferably performed with fast spin echo (FSE), fast gradient echo (GRE), 3D sequences or ‘black blood’ sequences, depending on the clinical suspicion, MRI equipment and sequence availability. Static pre- and post-contrast T1-weighted images or dynamic perfusion sequences during GBCA administration are obtained in accordance with indications for the pathology under study. T1-weighted perfusion sequences are performed for tissue characterisation and analysis of contrast kinetics while T2*-weighted perfusion sequences (dynamic susceptibility contrast [DSC]) are used to obtain information on capillary tissue perfusion and blood volume. The most commonly used doses and flows in the CNS are summarised in Table 4.

BreastMRI is highly sensitive in detecting breast cancer because tumour neoangiogenesis is more permeable and causes early GBCA extravasation36 (Fig. 2). The study is performed with a dynamic T1-GRE sequence, with or without fat suppression, preferably in the transverse plane. A pre-contrast series is acquired and a post-contrast series is obtained after the administration of a GBCA (Table 4). Post-GBCA acquisitions should be performed as early as possible, whether for cancer staging (Fig. 3), post-neoadjuvant response assessment or screening studies.36–38 A well-structured radiological report can be produced by following the protocol for image acquisition and post-processing.39

Fifty-nine-year-old woman with a palpable nodule in the left breast. Ultrasound-guided biopsy and pathological findings of invasive ductal carcinoma. Pre-adjuvant MRI in T1-GRE sequence with post-contrast fat suppression shows a single nodule with intense enhancement in the arterial phase (arrows).

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; GRE: fast gradient echo.

Forty-two-year-old woman diagnosed with high breast density. Nodule in the left breast biopsied in an ultrasound check-up with pathological findings of invasive ductal carcinoma. Pre-adjuvant MRI in T1-GRE sequence with post-contrast fat suppression shows the biopsied nodule and several disperse nodules with intense enhancement in the arterial phase (arrows).

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; GRE: fast gradient echo.

GBCAs are indicated in the study of multiple cardiovascular pathologies, including coronary artery disease. They can help to establish the prognosis and follow-up of ischaemic heart disease (Fig. 4),40 chronic coronary syndrome, cardiomyopathies, congenital heart disease, and cardiac masses, etc.25,41

Thirty-nine-year-old male. Cardiac MRI in late enhancement post-contrast sequence, in two-chamber plane. Demonstrates myocardial hypersignal in the lower basal and middle segments (arrows) due to retained contrast in the pathological myocardium due to infarction in the right coronary territory.

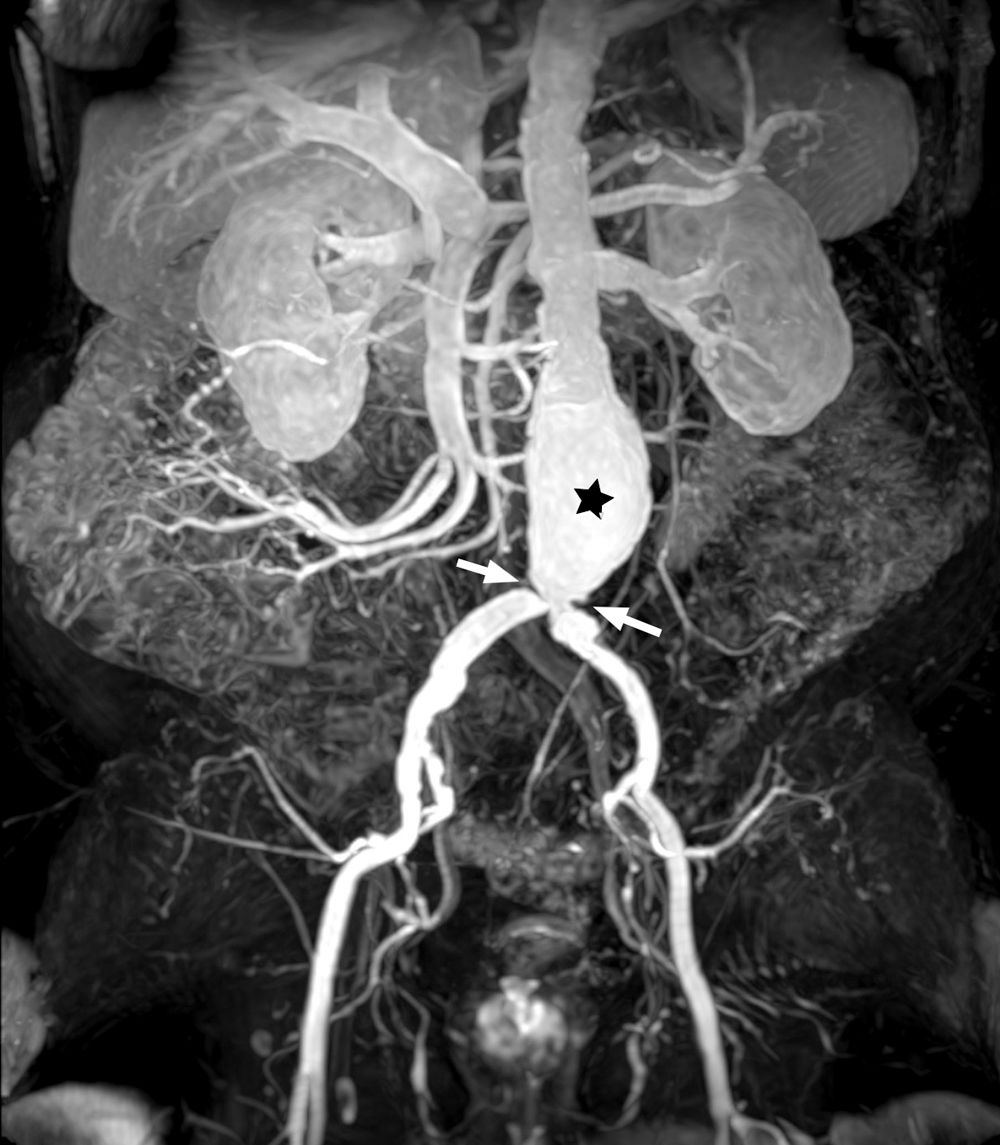

The dose, volume and rate of administration of GBCAs vary depending on whether first-pass perfusion, delayed enhancement or MR angiography studies are required (Fig. 5), but expert agreements have produced some standardised indications, which are listed in Table 4.23,42,43

Liver, pancreas, gall bladder and bile ductsExtracellular GBCAs are a fundamental part of multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) of the liver, pancreas, gallbladder and bile ducts, using a dynamic T1-GRE study with fat suppression and imaging acquired pre-contrast, during contrast administration (Table 4) and post-contrast of at least three phases: arterial, portal venous and interstitial or equilibrium.44 (Fig. 6).

Twenty-five-year-old woman diagnosed with jaundice and cholestasis. Liver MRI, T1-GRE sequence with fat suppression without contrast (a), and post-contrast in arterial (b), portal (c), and equilibrium (d) phases. Images show a 36 mm mass in segment VIII (arrows), well-defined, with intense and heterogeneous enhancement, and a hypointense centre in the arterial phase, which in the portal and equilibrium phases becomes mostly isointense with some central areas that remain hyperintense, in relation to focal nodular hyperplasia.

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; GRE: fast gradient echo.

GBCAs are indicated in MR enterography to identify the presence and severity of inflammatory activity and to detect complications. Generally, post-contrast T1-GRE images with fat suppression are obtained in the coronal plane in the portal phase (60 s) (Fig. 7), although some authors refer to the acquisition of four phases: non-contrast, arterial (20–25 s), portal (60 s) and equilibrium (120 s). After the coronal plane, T1-GRE sequences are performed with fat suppression in the transverse and sagittal planes.45,46

Twenty-year-old female. GBCA-enhanced MRI of the bowel demonstrates wall enhancement of a 7 cm segment of the terminal ileum (arrows), an 8 cm segment of the cecum and ascending colon (arrowhead), and wall enhancement of the descending colon (arrowheads), due to Crohn's disease, with inflammatory activity.

GBCA: gadolinium-based contrast agent; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

MRI is the preferred technique for identifying and characterising complex fistulae in order to determine the most effective treatment approach.47 3D T1-GRE sequences with fat suppression, oriented both in the transverse plane and coronal to the axis of the anal canal, both without and after the administration of a GBCA (Table 4), enhance the visualisation of fistulous tracts, granulation tissue, and the detection of abscesses.48,49

RectumGBCAs are not indicated in the initial assessment because they do not improve diagnostic confidence regarding the degree of local spread.50,51 They are not routinely used in post-neoadjuvant reassessments but in some cases they may be useful to detect tumour persistence through areas of heterogeneous enhancement51 and possible complications such as fistulisation or pelvic abscesses.52 GBCAs are indicated in cases of suspected local recurrence after treatment.

PeritoneumMRI of the peritoneum can provide information for the diagnosis and surgical planning of primary or metastatic peritoneal tumours.53 A dynamic 3D T1-GRE sequence in the transverse, coronal and sagittal planes of the abdomen, acquired five minutes after the administration of a GBCA, enables the assessment of abnormal areas of peritoneal enhancement, essential for the evaluation of tumour spread.54

Female pelvisMRI studies of the female pelvis are performed with different protocols depending on the type of pathology being studied.55 Given the diversity of the protocols, the most relevant aspects of the main pathologies are detailed below.

Cervical cancerMRI is indicated for baseline local staging, tumour response to chemoradiotherapy, and assessment of local recurrences. GBCAs are not indicated in the initial assessment or response to neoadjuvant therapy but they can be useful in ambiguous cases, particularly in the assessment of infiltration of adjacent structures. They are also indicated in cases of suspected relapse after treatment.55,56

Endometrial carcinomaGd-enhanced MRI is indicated to assess tumour size and depth of myometrial invasion. The T1-GRE sequence at two minutes and 30 s provides the best contrast between the tumour and the myometrium.55 The study can be performed with pre- and post-contrast sequence acquisitions or by obtaining a dynamic 3D T1-GRE sequence with fat suppression55,57 (Fig. 8).

60-year-old woman with intermenstrual bleeding. Endometrial growth in the body of the uterus (asterisks) extending to the internal orifice of the cervix. GBCA enables us to define the invasion of more than 50% of the myometrium and to exclude the invasion of the cervical stroma on the basis of the normal enhancement of the cervical mucosa (arrows).

GBCA: gadolinium-based contrast agent.

Dynamic T1-GRE sequences with fat suppression and Gd enhancement in the arterial, portal and equilibrium phases are useful for characterising and defining the extent of masses.58

Adnexal massesmpMRI is indicated to characterise adnexal masses when ultrasound is indeterminate. Gd-enhanced MRI, using a dynamic T1-GRE sequence or a pre- and post-contrast T1-weighted sequence, preferably in a transverse plane (parallel to the uterine body), is critical for detecting the enhancement of nodules, solid mural areas or areas of necrosis.55

EndometriosismpMRI is complementary to ultrasound if the latter is inconclusive or if more information is required for surgical planning.

There is no clear recommendation on GBCAs and they are optional in the initial diagnosis of indeterminate adnexal endometriosis and in the differential diagnosis with other pelvic pathologies.59

ProstateProstate cancer clinical guidelines recommend the use of mpMRI to diagnose prostate cancer in patients with elevated prostate specific antigen (PSA) prior to biopsy.60 The Prostate Imaging Reporting & Data System (PI-RADS®) 2.1 guidelines indicate a dynamic post-GBCA sequence to complement the assessment of the peripheral zone of the gland (Table 4).61

The most recent suggestion is to eliminate the dynamic post-contrast sequence and instead perform biparametric MRI using T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted sequences.62 However, abandoning post-contrast imaging would result in an increase in indeterminate lesions and an inferior detection of clinically significant prostate cancer, especially if interpretation is performed by less experienced professionals.63 There have been recent calls for further prospective studies so that evidence-based recommendations can be made on non-contrast MRI in the initial diagnosis of prostate cancer.64

A dynamic sequence with a GBCA should be included in the assessment of local recurrence after a prostatectomy or radiotherapy and in patients under active surveillance.65

Scrotum—testicleScrotal MRI is complementary to ultrasound66 because it provides useful information when ultrasound findings are inconclusive or inconsistent with clinical examination. It allows for: 1) differentiation between intratesticular and paratesticular lesions; 2) characterisation of intratesticular and paratesticular lesions; 3) differential diagnosis between germ cell tumours and testicular sex cord-stromal tumours; 4) local staging of testicular malignant neoplasms (in patients scheduled for testicular-sparing surgery); 5) differentiation between seminomas and non-seminomatous tumours (when immediate chemotherapy is planned and orchiectomy is delayed); 6) evaluation of acute scrotal pain and scrotal trauma; and 7) detection and localisation of undescended testis.67 MRI provides 100% sensitivity and 88% specificity in evaluating and characterising intratesticular masses, and in differentiating between those that are benign and those that are malignant.68 Scrotal mpMRI includes a coronal 3D T1-GRE sequence that acquires five to seven imaging sets both pre- and post-contrast administration.69

MusculoskeletalThe IV administration of a GBCA improves the diagnosis and assessment of the extent of musculoskeletal infections. It also helps to characterise and differentiate between focal cellulitis, abscesses, myositis, fasciitis, necrotising soft tissue infections, septic arthritis and bone infections.70 In the study of soft tissue masses, GBCAs are critical in the characterisation and assessment of the extent of the mass71 (Fig. 9).

65-year-old male with a mass in the left shoulder. T1-GRE MRI without contrast (a) and post-contrast in the arterial phase (b) demonstrates a 3 × 2 cm irregularly shaped mass (asterisk) in subcutaneous cellular tissue infiltrating the fascia and muscle compartment. The pathological diagnosis was lymphoma.

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; GRE: fast gradient echo.

Recently, the Society of Skeletal Radiology (SSR) has proposed a bone data and reporting system (Bone-RADS) and algorithms for the diagnosis of bone lesions. It specifies that in many circumstances GBCAs help diagnose bone lesions.72

Joint studies: Direct MRI arthrography is considered the most accurate imaging modality for the evaluation of intra-articular structures. The SSR has recently published a consensus document with recommendations on the use of MRI arthrography and its typical clinical applications.72 Direct MRI arthrography continues to be a key diagnostic procedure today and is especially useful when conventional MRI is inconclusive or the results are inconsistent with the clinical assessment.30

ConclusionsExtracellular GBCAs are the most widely used contrast agents in clinical practice. They are considered safe, enhance diagnostic capabilities, and are integral to standard protocols for assessing a variety of pathologies. The MRI diagnostic process can be enhanced across all areas of radiology by gaining a deeper understanding of their formulation, biodistribution, potential complications, and clinical indications.

Author contributions- 1

Research coordinators: RSF.

- 2

Study concept: RSF.

- 3

Study design: RSF.

- 4

Data collection: N/A.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: N/A.

- 6

Statistical processing: N/A.

- 7

Literature search: RSF, CMD, ERG.

- 8

Drafting of article: RSF.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: RSF, CMD, ERG.

- 10

Approval of the final version: RSF, CMD, ERG.

No grants or financial support have been received from any public or private institution.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.