To review and describe the most characteristic radiological findings of the most frequent esophageal tumor lesions, with emphasis on the esophago-gastric distention technique pneumo-computed tomography performed in our institution. To know the main advantage of this distension technique.

ConclusionMalignant tumor lesions (predominantly squamous cell carcinoma in the mid esophagus and adenocarcinoma in the distal esophagus) present as asymmetric wall thickening, mucosal irregularity, or mass extending into adjacent organs with lymph node involvement. Benign tumors (mainly leiomyoma being the most frequent and others such as lipoma) present as endoluminal growth, with defined borders and homogeneous attenuation. Post-contrast enhancement is scarce or moderate. The technique of computed tomography pneumotomography technique achieves an additional distension of the esophageal lumen in all cases. It allows delimiting the superior and inferior borders of the lesions, helping the surgeon to define the therapeutic strategy.

Revisar y describir los hallazgos radiológicos característicos de las lesiones tumorales esofágicas más frecuentes estudiadas mediante la técnica de Neumo-TC realizada en nuestra institución. Conocer la ventaja principal de esta técnica de distensión.

ConclusiónLas lesiones tumorales malignas (predominantemente el carcinoma de células escamosas en esófago medio y el adenocarcinoma en esófago distal) se presentan como un engrosamiento asimétrico de la pared, irregularidad de la mucosa, o masa que se extiende hacia órganos adyacentes con compromiso ganglionar. Los tumores benignos (principalmente el leiomioma, tumor del estroma gastrointestinal y lipoma) se presentan en forma de crecimiento endoluminal, con bordes definidos y atenuación homogénea. El realce post-contraste es escaso o moderado. La técnica de Neumo-TC logra una distensión del lumen esofágico adicional en todos los casos. Esto permite delimitar los bordes superior e inferior de las lesiones ayudando al cirujano a definir la estrategia terapéutica.

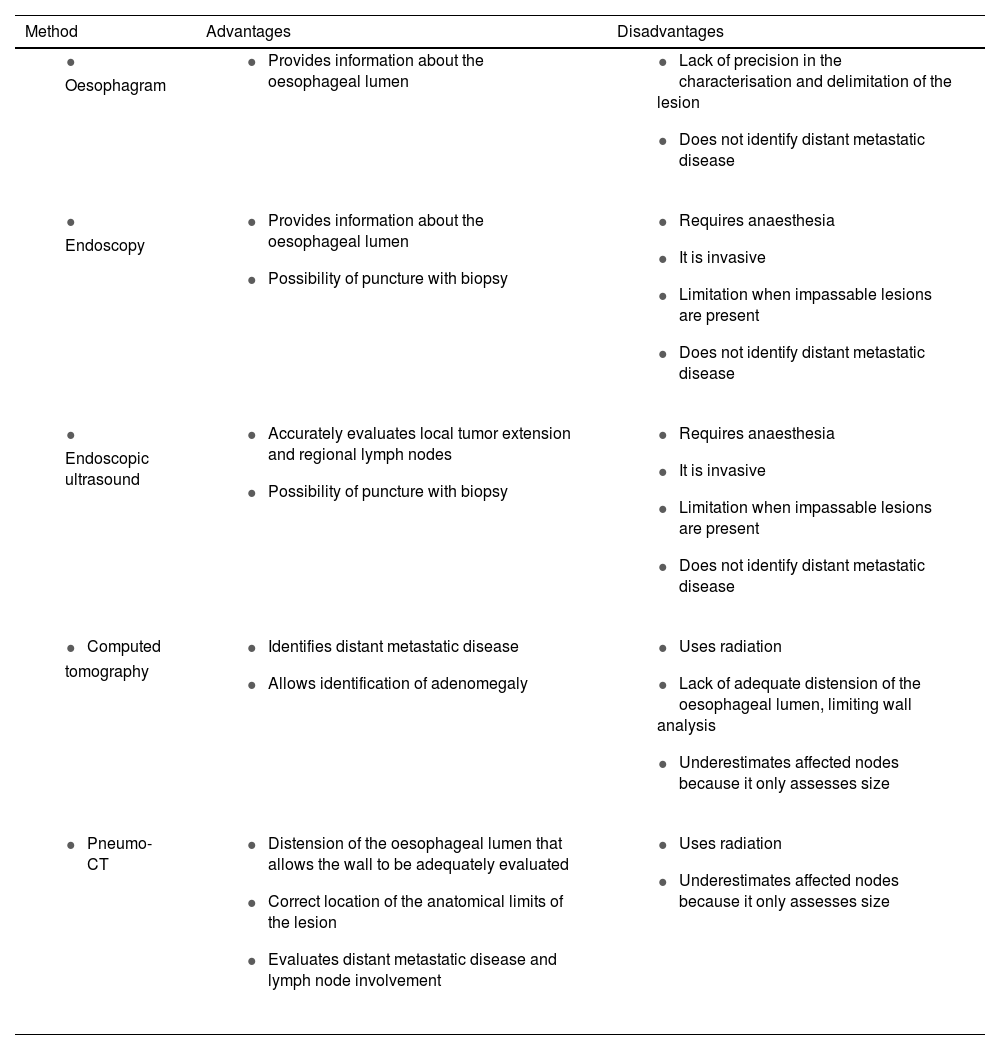

The oesophagus can be affected by a wide variety of benign and malignant tumors, with several types of presentation such as nodules, plaques, ulceration, stenosis or diffuse narrowing.1 There are several diagnostic methods for their evaluation, each offering different advantages and disadvantages (Table 1).

Summary of the advantages and disadvantages of the different methods of evaluating the oesophagus.

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Radiological studies have the advantage of dynamically assessing the passage of contrast through the oesophageal lumen, but a drawback is that they only indirectly show the imprint generated by mural or extrinsic lesions.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGE) is one of the best methods for direct evaluation of the lesion and has the advantage that a biopsy can be taken during the same procedure, although it is limited in tumor staging.

Endoscopic ultrasound is useful for tumor evaluation, its local extension and the presence of regional lymphadenopathy, although it is not able to evaluate possible distant metastases.2,3 Both methods are limited in the presence of an impassable stenosis.

The Pneumo-CT technique overcomes this disadvantage by distending the oesophageal lumen through constant and sustained insufflation of carbon dioxide. This allows a better characterisation of wall lesions as well as a global evaluation.4–7

To perform Pneumo-CT, the patient is required to fast for eight hours and intramuscular hyoscine is administered to achieve an antispasmodic effect. A Foley catheter is inserted transorally or transnasally until it reaches the inferior plane of the cricopharyngeal muscle. Carbon dioxide is insufflated through the catheter at a continuous and regulated pressure of between 15 and 25mmHg with an injection pump until maximum luminal distension is achieved. Tomographic acquisition of the neck, thorax, abdomen and pelvis is then performed. Subsequently, multiplanar, three-dimensional and virtual endoscopy reconstructions are performed for better visualisation of the shape and location of the lesion, as well as the size and parietal thickening.4

Consequently, this non-invasive technique is useful in terms of helping the surgeon to design the surgical approach by having iconographic information on the extent of the lesion, in addition to the possibility of detecting lymph node involvement of neighbouring and distant organs in a single study. Furthermore, it is indicated when it is impossible to perform general anaesthesia or in the presence of an oesophageal stenosis that cannot be passed with the endoscope.4

The objective of this article is to review and describe the characteristic radiological findings of the most common oesophageal tumor lesions studied using Pneumo-CT.

LeiomyomaIt is the most common benign intramural tumor of the oesophagus, although it is still relatively rare.8 It is usually solitary, and the presentation of multiple or diffuse lesions is very rare.9 It is more common in men than in women, with an average age of 44 years.10 It is located mainly in the middle and distal thirds of the oesophagus, where there is the greatest proportion of smooth muscle. The most commonly associated condition is the hiatus hernia, between 4.5–23%, although it is also related to other oesophageal conditions such as achalasia, motility disorders, oesophageal diverticula and gastroesophageal reflux.8 The most common symptom is dysphagia, followed by retrosternal pain, pyrosis or discomfort. Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, reflux, breathing problems, bleeding, or it may be asymptomatic.9

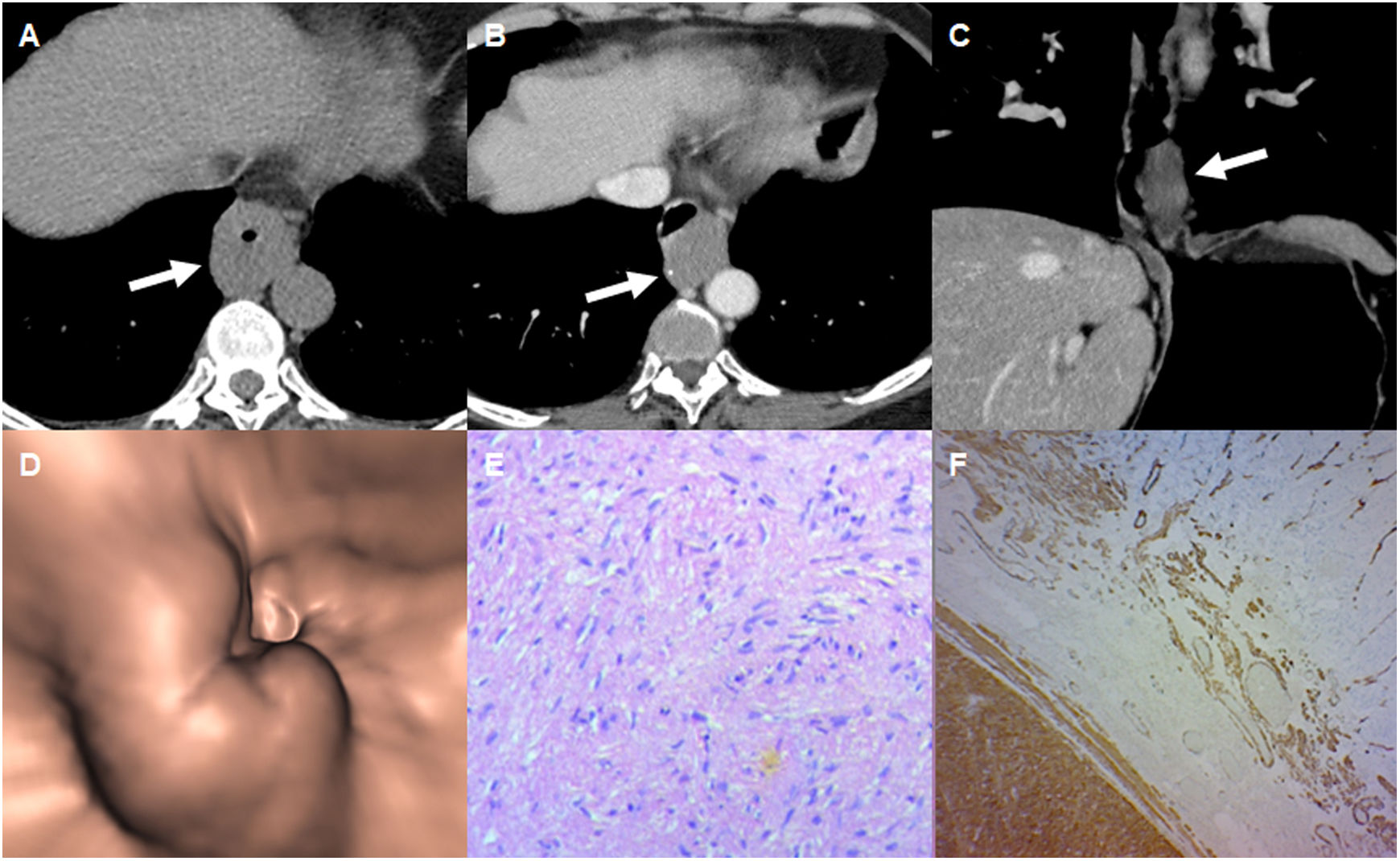

On Pneumo-CT it is visualised as a smooth or slightly lobulated mass, occasionally with calcifications. Very rarely it presents cystic degeneration, necrosis or ulceration (Fig. 1). It has homogeneous attenuation with a scant or moderate enhancement pattern with intravenous contrast and endoluminal growth.10,11 It should be remembered that while gross appearance and histology can help differentiate leiomyoma, it is difficult to distinguish it from a GIST unless immunohistochemistry testing is used. Histologically, leiomyomas show spindle-shaped cells with elongated nuclei and eosinophilic, fibrillar cytoplasm, often grouped, sometimes with calcifications and mild or no mitotic activity. They tend to be positive for desmin and smooth muscle, and negative for CD34 and KIT and c-kit.12 The difference should be borne in mind because leiomyomas do not metastasise and GISTs are associated with malignant transformation and metastasis. Therefore, surgical resection of leiomyomas is unnecessary unless they cause symptoms.11

64-year-old woman with endoscopy where an oesophageal lesion was observed. A) Axial reconstruction of chest CT without contrast and without distension. Apparent diffuse thickening of the distal oesophagus (arrow). B and C) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, in axial (B) and coronal (C) reconstruction. It shows the lesion to be semicircumferential, with defined contours with eccentric calcification (B) and little enhancement with intravenous contrast. D) Virtual endoscopy showing extrinsic compression of the oesophageal lumen by the tumor lesion. E and F) Histology demonstrating spindle cells without atypia arranged in interlaced bundles (E), with positive immunohistochemistry for smooth muscle actin (F), confirming the diagnosis of leiomyoma.

It is the second most common oesophageal mesenchymal tumor, after leiomyoma. Most occur when a person is in their 40s, 50s or 60s. They are mainly located in the distal third of the oesophagus and the gastro-oesophageal junction, commonly associated with dysphagia. In other cases, mucosal ulceration can lead to gastrointestinal bleeding, including haematemesis, melaena, and iron deficiency anaemia.

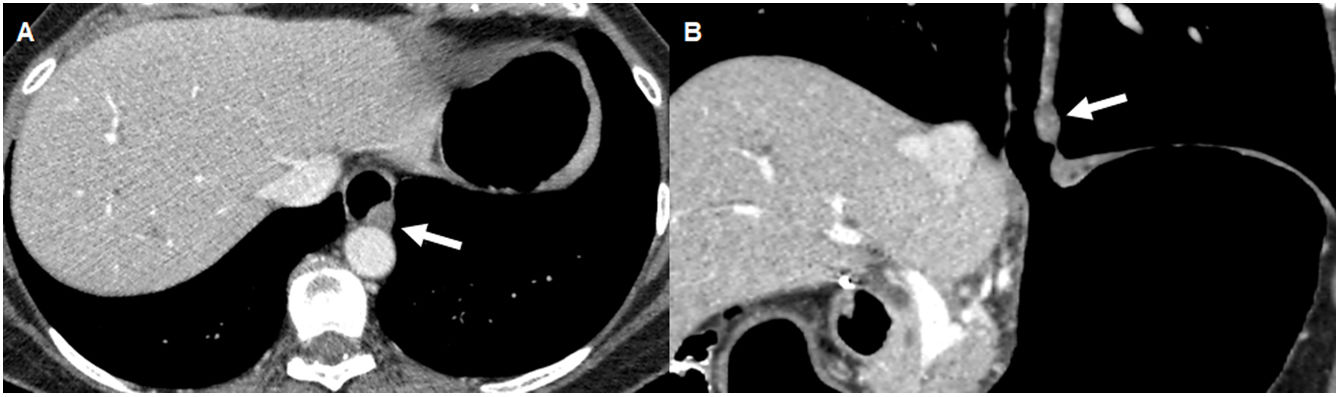

On CT they show predominantly exophytic growth, with or without the presence of ulceration. They behave variably with intravenous contrast since they can present both homogeneous and heterogeneous enhancement due to necrosis, haemorrhage or cystic degeneration, with or without ulceration (Fig. 2).12 They often have vessels inside them and, rarely, calcifications.

61-year-old woman being studied for a defect in oesophageal filling in the oesophagram, in a context of cough and heartburn. Axial (A) and coronal (B) reconstructions of Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast. Nodular lesion in the left lateral wall of the distal oesophagus, with exophytic and endoluminal growth (arrow). The biopsy was positive for CD117, being compatible with a GIST.

Metastases are more frequent through the haematogenous route than the lymphatic route, with the most common locations being the liver and peritoneum, followed by the soft tissues, the lung and the pleura.13

Immunohistochemistry is essential for diagnosis, as GISTs are positive for CD117 and often for CD34.

LipomaOesophageal lipoma represents 0.4% of benign tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Eighty-five percent are asymptomatic and incidental findings, while the symptomatic ones can manifest with dysphagia, epigastralgia or regurgitation depending on the size; in a lower percentage of cases they are associated with symptoms of bronchial aspiration and respiratory tract infection.

Lipomas are composed of adipose tissue surrounded by a fibrous capsule. It should be remembered that on CT they appear as a well-defined mass of low attenuation between −70 to −120 HU. Resection is only indicated in symptomatic cases (Fig. 3).14

65-year-old woman being studied for swallowing disorders, hypersalivation and cough, with a lipoma that could not be resected by endoscopy. Axial (A) and sagittal (B) reconstructions in the mediastinal window of a Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast. Lesion with fatty density and defined contours that occupies almost the entire oesophageal lumen (arrow). The lesion is pedunculated and originates from the anterior wall of the upper oesophagus (black arrow).

Eighty percent of oesophageal neoplasms are malignant and, of these, 90% are squamous carcinomas and adenocarcinomas.

Squamous cell carcinoma primarily involves the middle third of the oesophagus, followed by the lower third and then the upper third. They may have various macroscopic morphological patterns appearing as polypoid, flat or ulcerated lesions. Superficial ones affect the mucosa or submucosa and are usually flat, plaque-like or slightly elevated. The advanced ones are infiltrative, although they can also be polypoid, fungal or ulcerative.15

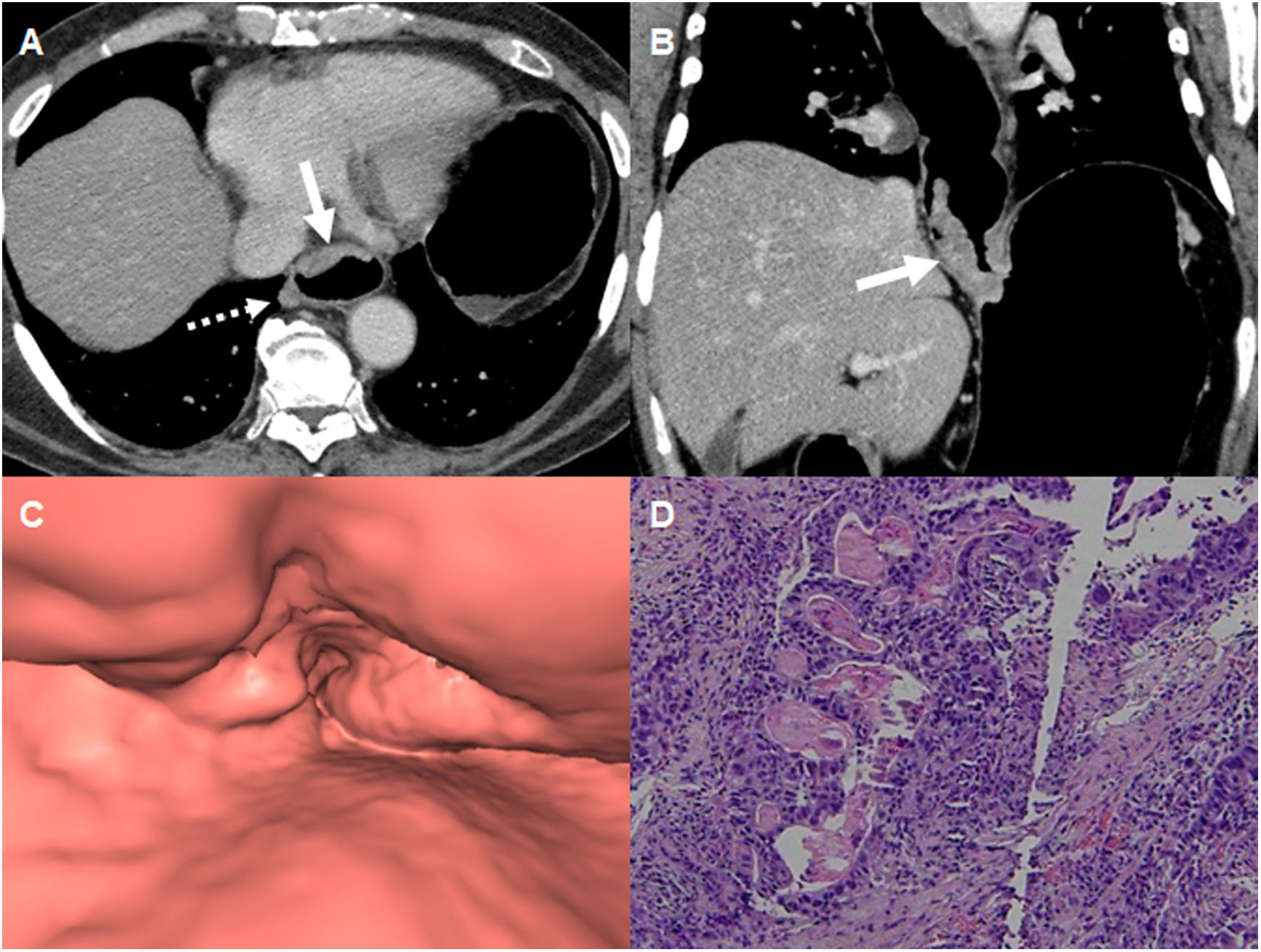

Adenocarcinoma affects patients over 50 years of age. The most important risk factor is the presence of Barrett's oesophagus, a pre-malignant condition where the normal squamous epithelium of the lower part of the oesophagus is replaced by intestinal columnar epithelium.16,17 The most common location is the lower third of the oesophagus and it tends to invade the cardia and fundus by direct extension through the gastro-oesophageal junction. The most common symptoms include progressive dysphagia, odynophagia and weight loss; in the case of mediastinal invasion, there may be chest pain unrelated to swallowing.15 On Pneumo-CT, it usually presents as a diffuse thickening of the oesophageal wall, as a polypoid lesion with scalloped edges and irregularity of the mucosa, or as a mass that projects into the lumen of the oesophagus (Fig. 4).15

71-year-old man undergoing study for dysphagia, with a diagnosis of infiltrating lesion in the distal oesophagus by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Axial (A) and coronal (B) reconstructions of a Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, showing asymmetric mural thickening on the anterior wall of the distal oesophagus (arrow) and adjacent adenopathy (dotted arrow). C) Virtual endoscopy shows irregular reduction of the oesophageal lumen. D) Histology with haematoxylin and eosin staining (×100) showing atypical gland-forming epithelial proliferation consistent with adenocarcinoma.

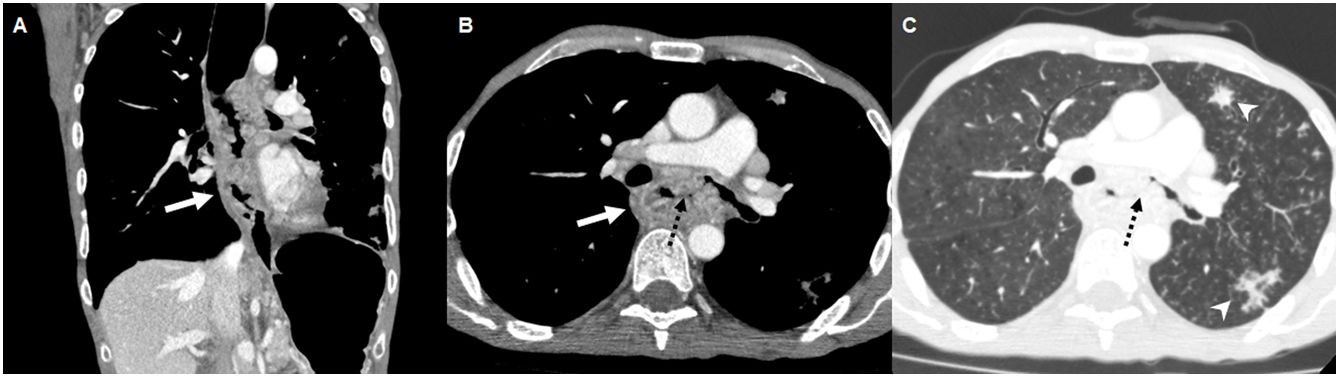

It must be remembered that both histological types are difficult to differentiate in imaging tests, although the role of Pneumo-CT is local and distant staging.18 To evaluate local invasion, infiltration of the fatty planes adjacent to the tumor and direct invasion of the aorta, trachea or bronchus must be considered, including the presence of fistulas (Fig. 5).19 The most affected distant organs are the liver, lungs, bones and adrenal glands. The presence of any of these findings forces us to consider the possibility of an unresectable tumor.20

A 55-year-old man referred from another centre due to a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus, a Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast was requested for staging. Coronal (A) and axial (B) reconstructions in mediastinal window show a circumferential mural thickening with a raised and ulcerated appearance in the middle oesophagus (arrow), which generates a severe stenosis of the lumen and invades neighbouring structures with a fistula between the oesophageal lesion and the left main bronchus (dotted arrow). C) Axial reconstruction in lung window shows the oesophagobronchial fistula (dotted arrow) and secondary pulmonary nodular lesions (arrowheads).

Oesophageal involvement by lymphoma is usually secondary to local invasion from the stomach or mediastinum, and represents less than 1% of all gastrointestinal lymphomas, with primary oesophageal lymphoma being extremely rare.21 The most common histological type in the oesophagus is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.15

It may present with dysphagia, but many patients are asymptomatic, and its most common location is the distal third of the oesophagus. It must be remembered that on CT it can present in various forms: as a polyp, an ulcerative lesion, a concentric and asymmetric mural thickening, multifocal nodules, thickening of folds, or less frequently as aneurysmal dilations of the oesophagus. Although these findings are similar to other entities, the presence of mediastinal lymphadenopathy or an intact fatty plane between the tumor mass and neighbouring structures is suggestive of lymphoma (Fig. 6).22

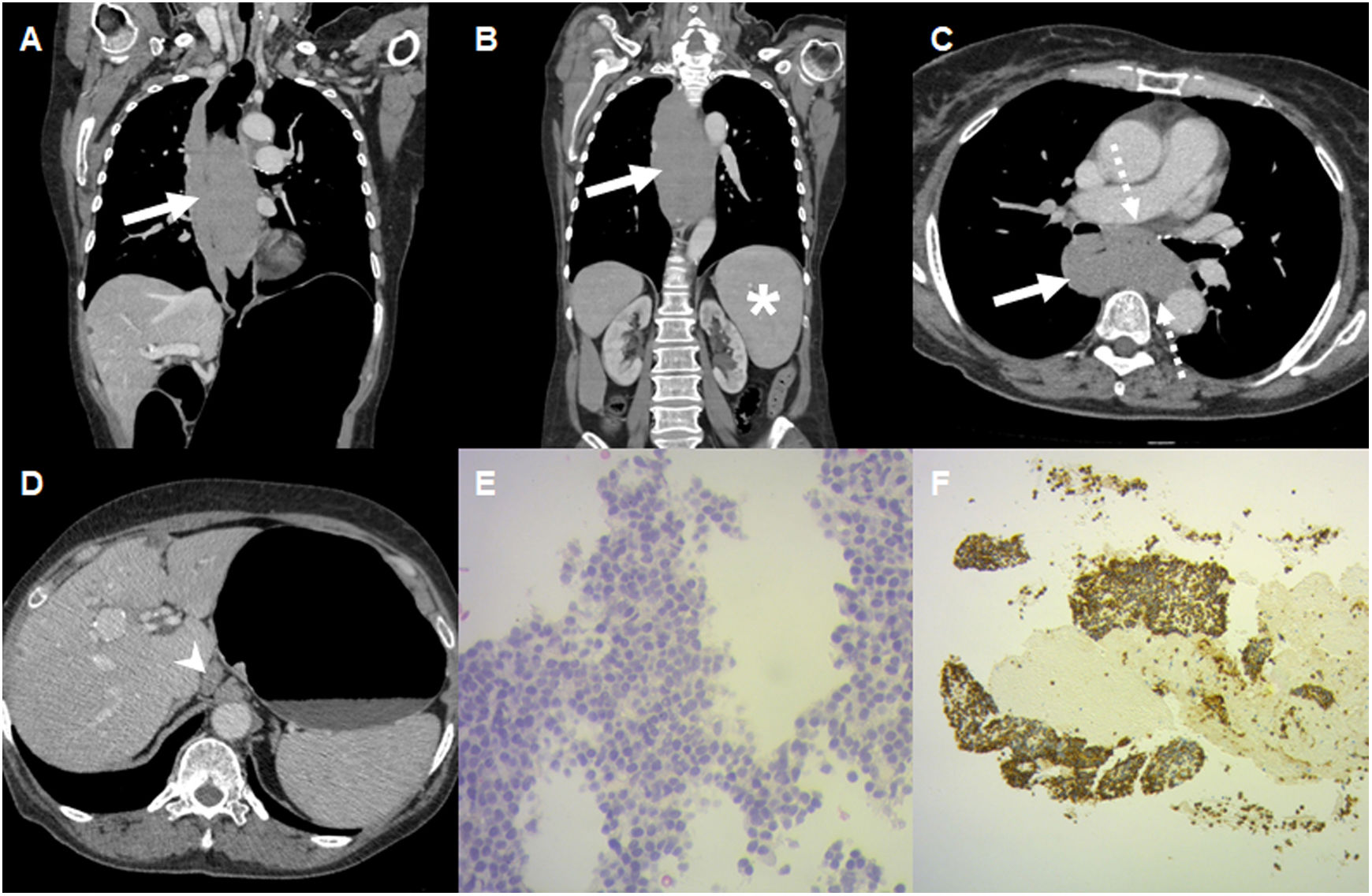

65-year-old woman undergoing study for an oesophageal lesion with biopsy with insufficient material from another centre. Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast. Coronal (A and B) and axial (C and D) reconstructions in mediastinal window, showing extensive concentric and asymmetric mural thickening of the entire oesophagus (arrows) with little enhancement with intravenous contrast, and in intimate contact with the neighbouring structures, but without apparent invasion (dotted arrows). Note the splenomegaly (*) and adenomegaly in the gastrohepatic ligament (arrowhead). E and F) Endoscopy with biopsy was repeated, which reported diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Photomicrography (×40, H&E stain) shows numerous large and pleomorphic lymphoid cells with prominent nucleoli (E), with an immunophenotype with predominance of CD20 (F).

This is a very aggressive tumor, presenting with dysphagia, in patients with an average age of 60 years. The lesions usually present as non-obstructive polyps. It should be remembered that primary melanoma is 10 times more common than metastatic melanoma, with primary melanoma representing 0.1−0.2% of oesophageal neoplasms.23 The oesophagus lacks melanoblasts, the precursors of melanocytes, so it is postulated that there may be an aberrant migration of melanocytes to the oesophagus during embryogenesis.23 On CT it appears as a lesion with soft tissue density, homogeneous or heterogeneous, and it may show enhancement in the arterial phase (Fig. 7). In endoscopy they can be observed as pigmented lesions, although they do not always present this way since there is a group of pigmented lesions that must be confirmed by immunohistochemistry due to the positivity of S-100, MELAN-A and HBM-45 proteins.24

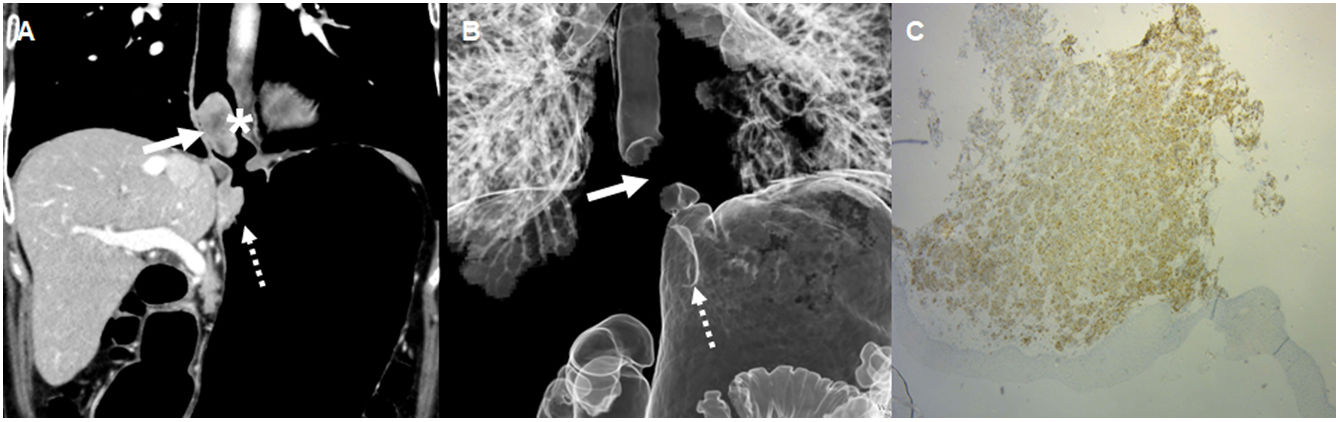

80-year-old woman being studied for dysphagia and weight loss, with upper gastrointestinal endoscopy that showed hyperpigmented lesions. A) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, coronal reconstruction, showing in the distal third of the oesophagus a nodular lesion with soft tissue density and heterogeneous enhancement with intravenous contrast that protrudes into the oesophageal lumen and reduces its calibre (*). A lesion with similar characteristics is observed below in the gastric subcardia (dotted arrow). B) Three-dimensional reconstruction with lung window showing the absence of lumen in the distal third of the oesophagus caused by the lesion (arrow) and the imprint of the gastric lesion on the subcardia (dotted arrow). C) Positive immunohistochemistry for MELAN-A, being compatible with melanoma.

These are not neoplasms, but malformations of the oesophagus that can cause symptoms similar to the lesions previously described. These lesions include congenital developmental cysts, duplications, inclusion cysts and neuroenteric cysts. They are less common in the oesophagus than in other locations of the digestive tract. They are generally asymptomatic, although they can cause dysphagia due to oesophageal compression.

On CT they are seen as a cystic image with liquid content, although previous infections can alter this attenuation (Fig. 8).25 Additionally, the wall may be slightly thicker than that of a bronchogenic cyst.26

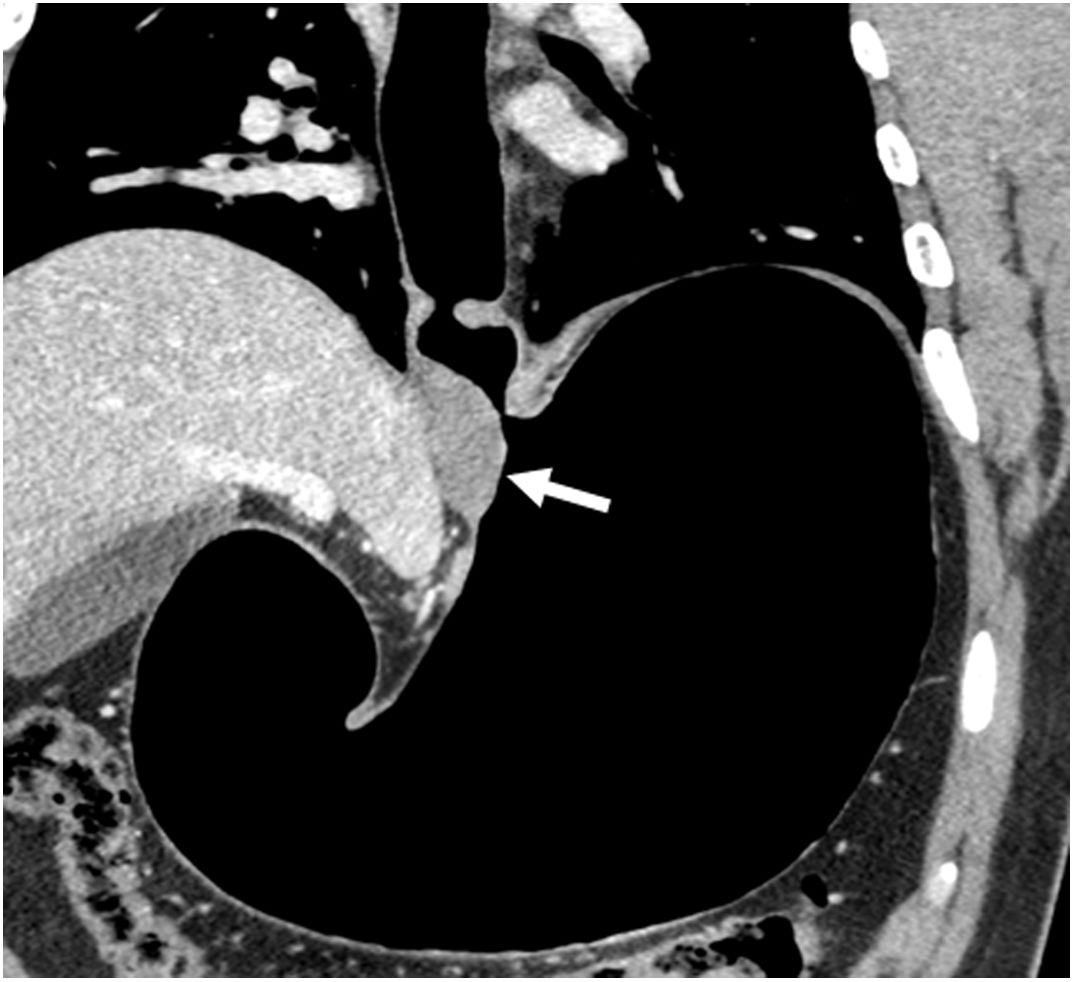

30-year-old man with incidental finding of an oesophageal lesion on an abdominal CT without distension performed for abdominal pain. Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, coronal reconstruction, showing in the wall of the gastro-oesophageal junction a hypodense image with defined edges, without enhancement with intravenous contrast (arrow), which was interpreted as a duplication cyst. Endoscopy confirmed the diagnosis.

Complications include carcinoma arising within the cyst or peptic ulceration if they involve the gastric mucosa.27

Oesophageal varicesOesophageal varices are dilated submucosal veins of the oesophagus and an important portosystemic collateral pathway associated with portal hypertension. It is important that they be detected due to the risk of haemorrhage, manifested by haematemesis, melaena, syncope or even hypovolaemic shock.

They are easily recognisable on CT as tortuous, dilated and enhancing tubular structures which can protrude into the oesophageal lumen.28 In addition, the oesophageal wall is usually thickened (Fig. 9).

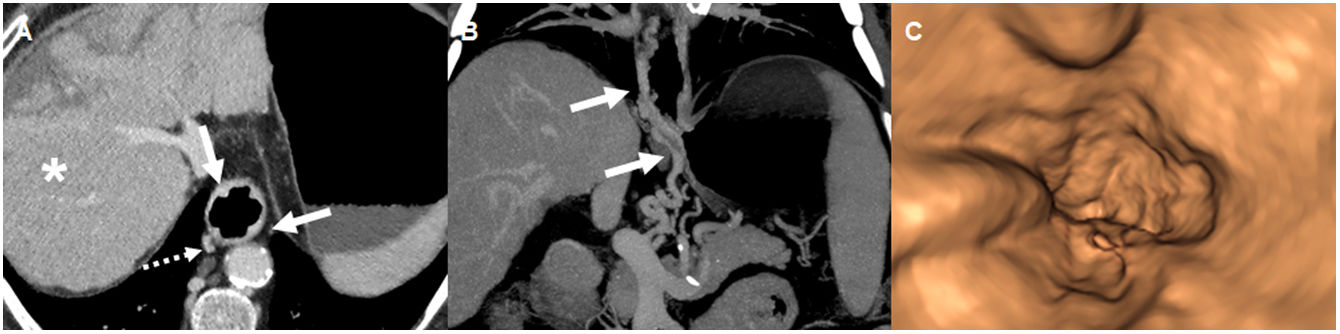

68-year-old man with T1 oesophageal cancer diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound and a history of alcoholic cirrhosis, in staging plan. Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast. Axial reconstruction (A), showing thickening and irregularity of the distal third of the oesophageal wall due to oesophageal varices (arrows). Note the para-oesophageal varices (dotted arrow) and liver cirrhosis (*). B) Coronal reconstruction with maximum intensity projection that highlights the oesophageal varices (arrows). C) Virtual endoscopy shows the imprint of the varices on the oesophageal lumen.

Malignant tumor lesions (predominantly squamous cell carcinoma in the middle oesophagus and adenocarcinoma in the distal oesophagus) present as an asymmetrical thickening of the wall, an irregularity of the mucosa, or a mass that extends into adjacent organs with lymph node involvement. Benign tumors (mainly leiomyoma, GIST and lipoma) present in the form of endoluminal growth, with defined borders and homogeneous attenuation. Post-contrast enhancement is poor or moderate. The Pneumo-CT technique achieves additional distension of the oesophageal lumen in all cases. It allows the thickening of the oesophageal wall to be identified and the upper and lower borders of the lesions to be delimited, helping the surgeon to define the therapeutic strategy. It helps evaluate local tumor extension and regional lymph node involvement, in addition to extra-oesophageal and distant disease in a single examination.

FundingThis study received no specific grants from public agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

AuthorshipResponsible for the integrity of the study: FC, NR and RLG.

Study conception: RLG and LS.

Study design: RLG and MU.

Data acquisition: FC, NR and JPS.

Data analysis and interpretation: FC, NR, RLG and LS.

Statistical processing: N/A.

Literature search: FC, NR, RLG and JPS.

Drafting: FC, NR, RLG, LS, JPS and MU.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: LS, JPS y MU.

Approval of the final version: Fiorella Conca, Nicolás Rosso, Roy López Grove, Lorena Savluk, Juan Pablo Santino and Marina Ulla.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.