In the multidisciplinary treatment of pediatric oncologic patients, multiple imaging tests, biopsies, and resections are required for diagnosis, initial staging, and posterior restaging. In these patients, pulmonary nodules are not always metastases, so the correct diagnosis of these lesions affects their treatment and the patient’s survival. Percutaneous localization of pulmonary nodules is key for two reasons: it enables the surgeon to resect the smallest amount of lung tissue possible and it guarantees that the nodule will be included in the resected specimen. Without percutaneous localization, it can be impossible to accomplish these two objectives in patients with very small nodules that are separated from the pleural surface and therefore impossible to see by thoracoscopy. This article reviews the technique for hook-wire localization of pulmonary nodules and the keys to ensuring the best results.

En el tratamiento multidisciplinar del paciente oncológico pediátrico se va a requerir de múltiples pruebas de imagen, tomas de biopsias y resecciones tanto para el diagnóstico como para la estadificación inicial y reestadificación posterior. La existencia de nódulos pulmonares en estos pacientes no siempre es sinónimo de metástasis, por lo que un correcto diagnóstico influirá en su tratamiento y supervivencia. La localización percutánea de los nódulos pulmonares es clave en dos aspectos: por un lado, permite al cirujano resecar la menor cantidad de tejido pulmonar posible, y por el otro garantiza la inclusión del nódulo en la pieza de resección, ya que sin nuestra ayuda esta labor puede ser imposible (nódulos de muy pequeño tamaño, separados de la superficie pleural y por tanto no visibles con el toracoscopio). Presentamos una revisión de la técnica de localización de nódulos pulmonares con arpón para resección toracoscópica con claves para mejorar la misma.

The appearance of a solitary pulmonary nodule as an incidental finding in a paediatric non-oncology patient may raise a problem of follow-up, but rarely represents a malignant nodule; hence, acquisition of histology samples usually does not figure in these patients’ diagnostic algorithm.1–3 However, cases of such patients with a history of cancer often require a histological diagnosis for staging and treatment planning.

The lungs are the organs to which most paediatric solid neoplasms most often metastasise. Osteosarcoma, Wilms tumour (nephroblastoma), tumours from the Ewing sarcoma family of tumours, rhabdomyosarcoma and hepatoblastoma are the primary cancers in children that most often initially present lung metastases or develop them over the course of the disease.4 However, 30%–60% of nodules correspond to benign conditions: granulomas, post-radiotherapy scarring, intrapulmonary lymph nodes, changes caused by chemotherapy, partial atelectasis or even lipid deposits.5,6

The management of pulmonary nodules—whether they appear at the onset or over the course of a disease—depends on numerous variables: on the one hand, the radiological characteristics of the nodule and, on the other, essentially, the primary tumour type, the patient’s initial stage and the patient’s baseline condition.7

The two techniques most commonly used to resect these pulmonary nodules are open thoracotomy and thoracoscopy.

In a short period of time, thoracoscopy has become standard practice for resection of pulmonary nodules.8 For small nodules not in contact with the pleural surface, and therefore neither palpated nor visualised, several procedures that precede thoracoscopic surgery have been developed: marking using a localization guide (microcoil or hookwire), marking using staining (methylene blue is most commonly used), marking using radiosurgery (radioguided occult lesion localization [ROLL]), marking with electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy and even combination techniques.9–13 The majority of cases require interventionist techniques in which computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound guides marker placement. Each technique has its own advantages and disadvantages yet there are few articles11,13,14 comparing techniques in terms of efficacy, safety and complications.

Open thoracotomy is usually reserved for patients who have undergone multiple prior thoracotomies and cases in which lesion location precludes a proper approach in thoracoscopy.

Selection of nodules to be biopsiedThe objectives of thoracoscopic resection are:

- •

In the majority of solid neoplasms, histological confirmation of the presence of metastasis.

- •

In osteosarcoma, histological diagnosis and resection of all or most nodules to decrease the stage of the tumour and redesign the patient’s oncology treatment. To achieve this objective in as few operations as possible, an attempt is made to simultaneously place multiple hookwires in one or even both lungs in a single procedure, which complicates the technique and lengthens the procedure.

Planning of hookwire marking is carefully agreed upon between oncologists, thoracic surgeons and radiologists. Given that, except in rare cases (perifissural nodule, calcified nodule in patients without osteosarcoma), no specific radiological characteristics enable definitive determination of which nodule has the most marked appearance of metastasis,1–3,5,15 the criteria that guide the selection of the nodule to be examined are:

Accessibility: the location of some nodules poses an obstacle to their proper CT-guided marking; examples include central nodules (nodules close to the hilum of the lung) and nodules at the height of the scapula or at the apex of the lungs.

Size: selection tends to favour larger nodules, which allow for acquisition of a larger histological sample, or ones that have grown since prior examinations.

Location: nodules found in the peripheral two thirds of the lung are preferable to those located centrally. Small nodules in contact with the pleura are associated with higher rates of pneumothorax and accidental dislodging.

Indications for percutaneous localization of pulmonary nodules in paediatric oncology patientsAt the onset of the disease:

- •

For tumours belonging to the Ewing sarcoma family of tumours, if there is questionable evidence of metastasis (i.e. one nodule measuring 5−10 mm or multiple modules measuring 3−5 mm) and it is recommended in the presence of one or more isolated nodules not meeting these criteria (one or more nodules <3 mm).7

- •

It is not recommended in all other paediatric solid neoplasms. Based on their size and number, some nodules are considered definitive metastases, while small nodules represent questionable evidence of metastasis requiring follow-up.7

- •

In Wilms tumour, pulmonary nodules smaller than 3 mm are not considered metastases according to the 2016 UMBRELLA protocol.16

- •

Sample acquisition is not recommended in pulmonary metastases of thyroid cancer: thyroid cancer metastases have a characteristic miliary pattern that does not require histological identification.

- •

It is recommended that a tissue sample be taken in all of the most common solid neoplasms in children. In these cases, one or two nodules can be selected for resection.

- •

It is recommended to perform atypical resection of all nodules or as many nodules as possible in osteosarcoma for disease monitoring and restaging.14

Information and consent: family members or legal guardians are informed of the technique and its complications by the oncologist and paediatric surgeon, and informed consent for the joint procedure is obtained. On the day of the procedure, the radiologist ensures that the steps of the procedure have been properly understood and provides more detailed information on the body position the patient will adopt, the number of hookwires to be inserted and the estimated duration of the procedure. The radiologist also informs them that they will be able to accompany the patient during transfer to the operating theatre, although this is done with the patient under general anaesthesia.

Anaesthesia: all procedures are performed under general anaesthesia. Both image acquisition and needle advancement are always performed in apnoea, since lung volume at the end of expiration is more reproducible than inspired volumes.

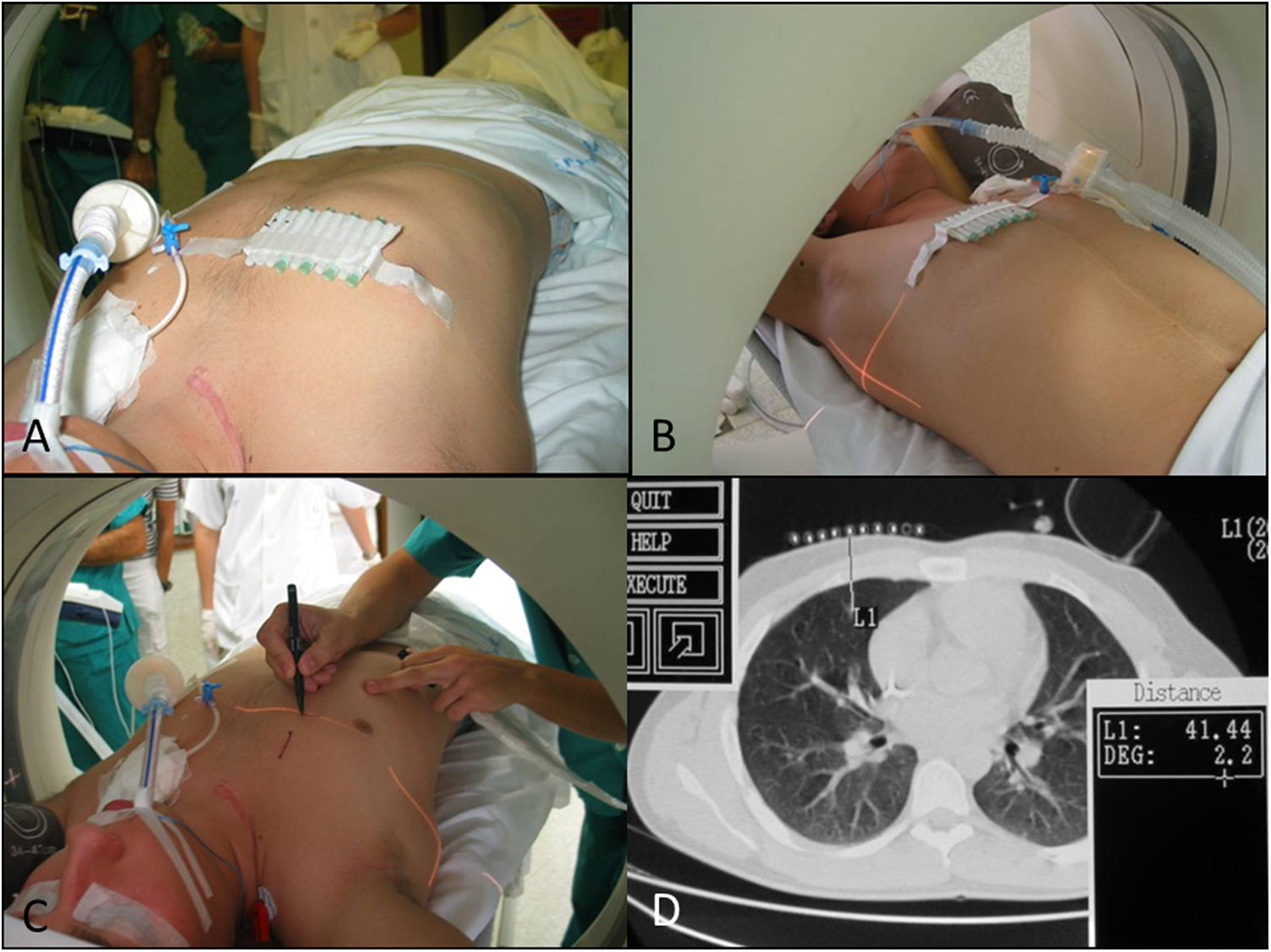

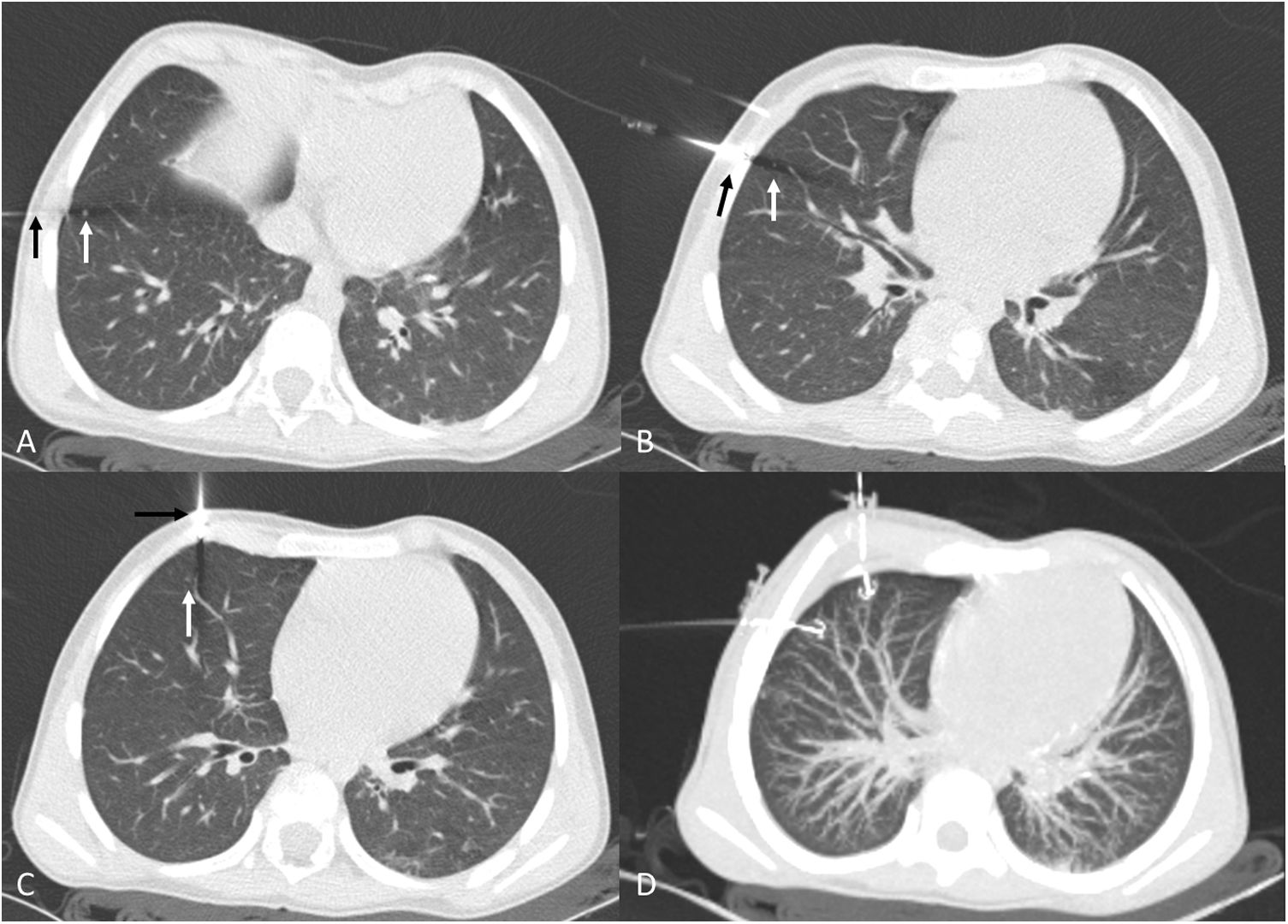

Patient position and radiological technique: the approach and therefore the position of the patient, which will be maintained throughout transfer to the operating theatre, are decided upon by mutual agreement between radiologists, thoracic surgeons and anaesthetists (Fig. 1).

Patient with a history of Ewing sarcoma in the right clavicle. Planning of the localization of a nodule in middle lobe segment 5. A) Placement of skin markers. B and C) Level selection by computed tomography (CT) laser light. D) Correspondence with CT imaging at the height selected. Distance from the skin of 4 cm.

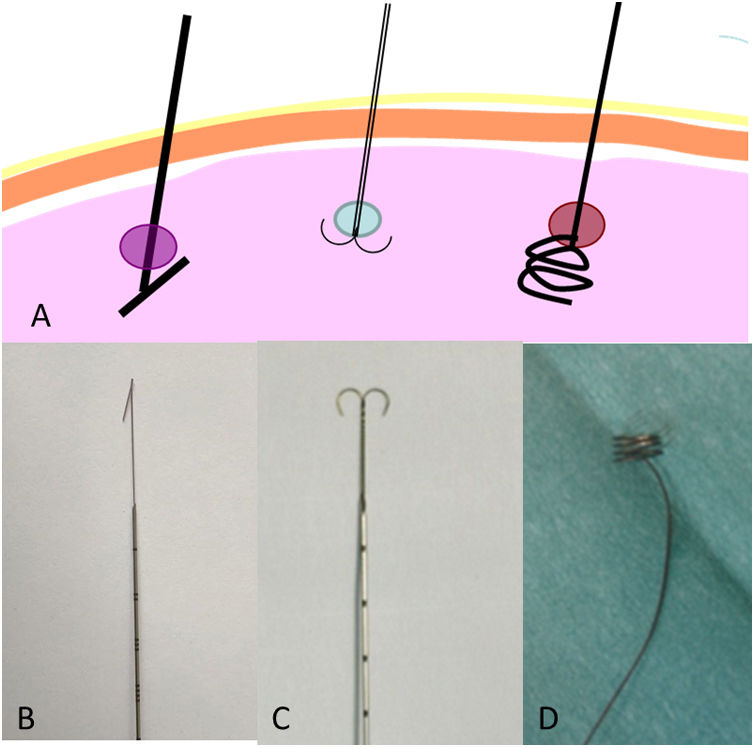

There are multiple types of hookwire (Hawkins, spiral and dual) (Fig. 2). The choice will depend on the preferences of the team of radiologists/surgeons. There are no studies comparing the efficacy and safety of each type. In our experience, the classic Kopans hookwire cuts the tissue, since lung tissue is more lax than breast tissue. It has a stronger tendency to move (advance or go backwards) and dislodge during surgery. The spiral hookwire,17,18 specifically designed for the lungs, also has a tendency to dislodge, since its spirals unwind with traction. However, it does have an advantage: the option to advance or go backwards by simple rotation.

Our centre uses the “anchor” (dual) hookwire, as our thoracic surgeons find that it is more stable and less prone to advancing or dislodging during surgery.

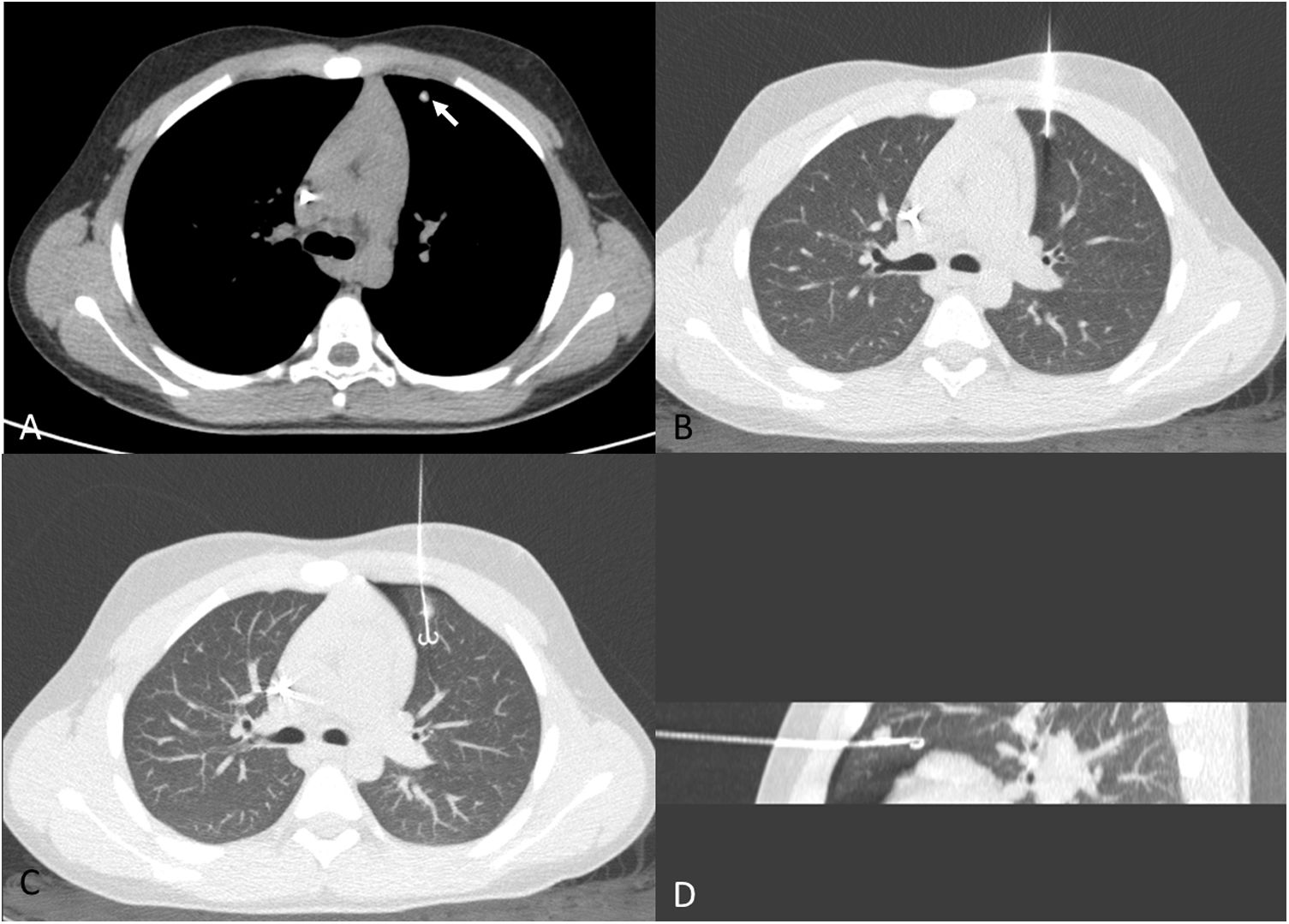

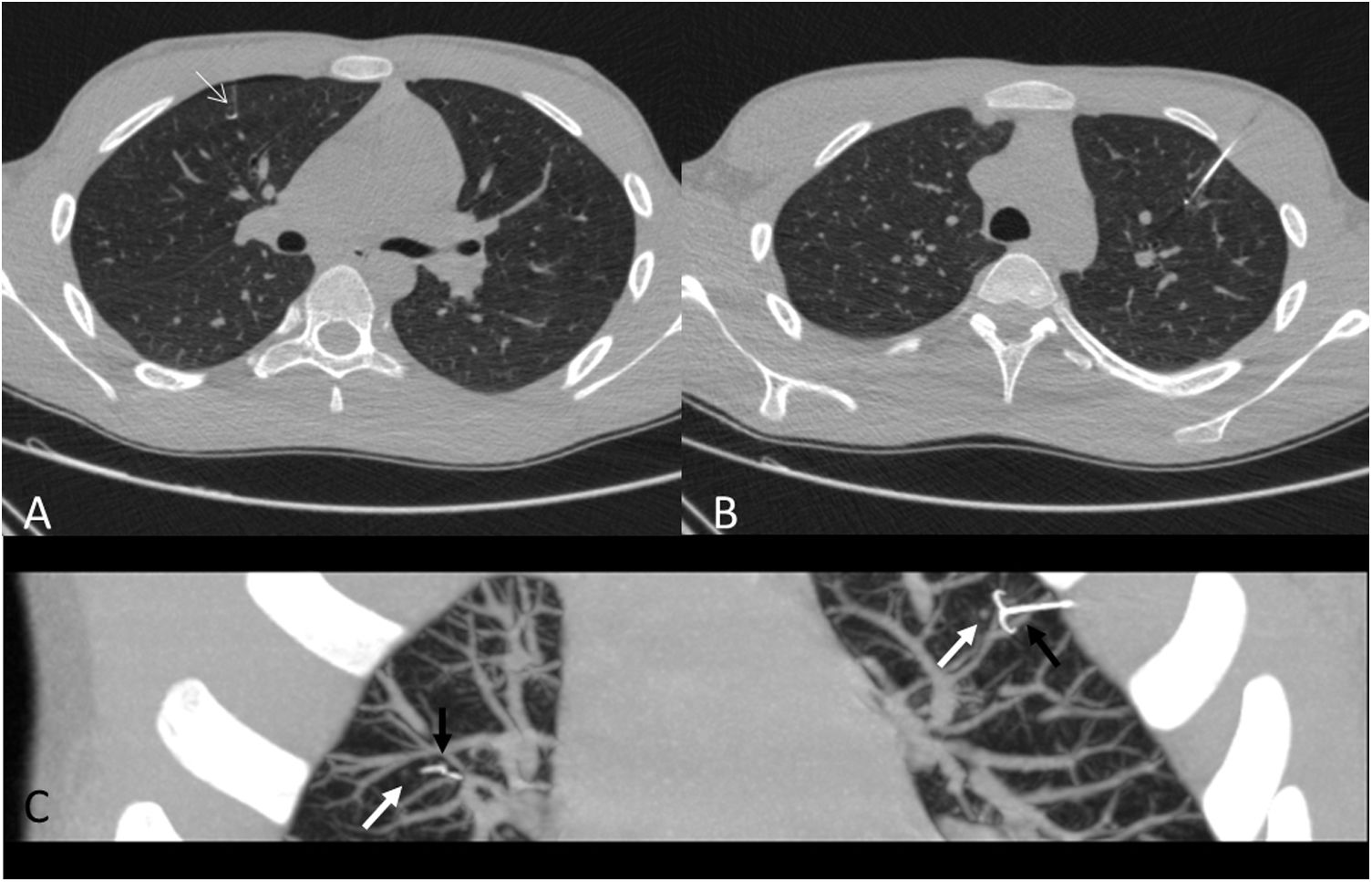

Insertion techniquePerpendicular entry: access to the nodule will be gained via the shortest path, with entry perpendicular to the pleural surface (Fig. 3). On the one hand, this approach facilitates wedge resection of a smaller amount of tissue and is associated with a lower rate of complications. Higher rates of dislodgement have been reported when the hookwire enters at an acute angle relative to the pleural surface.13 However, a fissure must not be crossed to reach the nodule: the hookwire must enter the lobe in which the nodule is located. For this reason, entry at an acute angle relative to the pleural surface is sometimes necessary (Fig. 4).

A 12-year-old boy with a history of osteosarcoma of the distal femur. A) Calcified nodule of recent onset in the left upper lobe (white arrow). B) Approach perpendicular to the pleural surface. As image B was acquired in apnoea, lung volumes are smaller than in image A, which was acquired in sustained inspiration. C) Hookwire release. Minimal anterior pneumothorax, with no clinical repercussions. D) Sagittal maximum intensity projection (MIP) reconstruction of the release of the hookwire and its position in relation to the nodule. Pathology results positive for osteosarcoma.

Release of the hookwire adjacent to the nodule: with no need to cross it to prevent the uncommon event of tumour spread along the trajectory. It is also not advisable to release the hookwire far beyond the nodule, since this results in unnecessary resection of a larger amount of non-pathological lung tissue.

Marking a single nodule:

- •

The height and level of the pulmonary nodule is marked using skin markers and CT laser guidance, the sterile field is prepared, and the preloaded needle is advanced.

- •

A check is performed in the middle of the procedure when the needle has been inserted in the chest wall but has not yet reached the pleural surface.

- •

If the direction of the preloaded needle is correct, it is advanced with the hookwire up to the depth measured on source imaging from the skin to the height of the nodule or slightly beyond it. The position is confirmed and the hookwire is released.

Marking multiple nodules:

- •

If the patient has multiple nodules that require resection, it will be possible to mark one lung per procedure (Fig. 5) or all anterior nodules (Fig. 6) in one procedure and all posterior nodules in another. The technique used is similar to that with a single nodule, with some specific considerations.

Figure 5.Simultaneous placement of three lung hookwires in an eight-year-old patient with a history of nephroblastoma and pulmonary nodules for preoperative treatment. Despite their small size (3 mm), a committee decision was made to determine whether viable tumour remained in these nodules in order to determine the duration of treatment with actinomycin/vincristine/doxorubicin (AVD). A) Presentation of localization (black arrow) of nodule (white arrow) in right lower lobe. B) Presentation of localization (black arrow) of nodule (white arrow) in the lateral segment of the middle lobe (ML). A) Presentation of localization (black arrow) of nodule (white arrow) in the medial segment of the ML. D) Axial MIP reconstruction of hookwires released in ML. The pathology results were negative for malignancy.

Figure 6.Placement of a hookwire in each lung for marking two nodules in an anterior location in a 14-year-old patient with a history of epithelioid sarcoma, which were negative for malignancy. A) Localization of nodule (white arrow) in right upper lobe. B) Localization of nodule in left upper lobe. C) Oblique MIP reconstruction showing the simultaneous release of both hookwires (black arrows) adjacent to the millimetric nodules (white arrows).

- •

The needles are advanced through the chest wall until they are close to the pleural surface, similar to when marking a single nodule. Any needles that have not arrived at their respective nodule without coming into contact with the pleural surface are repositioned.

- •

All the hookwires are advanced at the same time until each has reached or gone just beyond their corresponding nodules. It is important to complete this step simultaneously rather than consecutively, because the onset of pneumothorax changes the localization of the rest of the nodules. This would require the needles to be repositioned, which would increase the duration of the procedure and the dose given to the patient.

The lungs are organs in constant motion, which promotes hookwire movement and dislodgement. The rate of dislodgement in children is higher than in adults, since a child’s chest wall is very thin and the hookwire is advanced only a few centimetres into his or her lung.12 Some authors have proposed avoiding the subscapular musculature, given that inadvertent contractions thereof can more easily dislodge the hookwire.9

Fixation of the hookwire to the skin has been reported to increase the dislodgement rate.13,17 However, other authors have found that proper fixation of the hookwire to the skin is essential for preventing its accidental dislodgement during transfer to the bed and transfer of the patient to the operating theatre.18

Implementation of the techniqueHybrid operating theatres with CT significantly improve all aspects of the technique:

- •

Patient safety, since transfer to a bed, transfer to the operating theatre (with the patient anaesthetised) and subsequent transfer of the patient to the operating table are not necessary.

- •

This decreases the rate of accidental dislodgement of the hookwire, because it decreases the time between marking and surgery.

- •

For marking with staining, it decreases the risk of the stain used spreading to the rest of the lung.

- •

It decreases the likelihood of formation of clinically significant pneumothorax.

- •

It decreases surgery duration and anaesthesia time.

Combination techniques have been reported in which the nodule is marked with methylene blue or autologous blood12 and with a hookwire (dual technique); in this case, if hookwire dislodgement occurs, the lung area remains marked with the staining. Methylene blue as a sole marking method diffuses easily13 through the lung tissue, causing resection to tend to be more extensive than is actually required. It is also possible to use two hookwires with different routes of entry to mark a single nodule.

Puncture with an advanced navigation system decreases planning time, procedure duration and the dose administered to the patient, and increases the rate of success, which makes it highly advisable.17

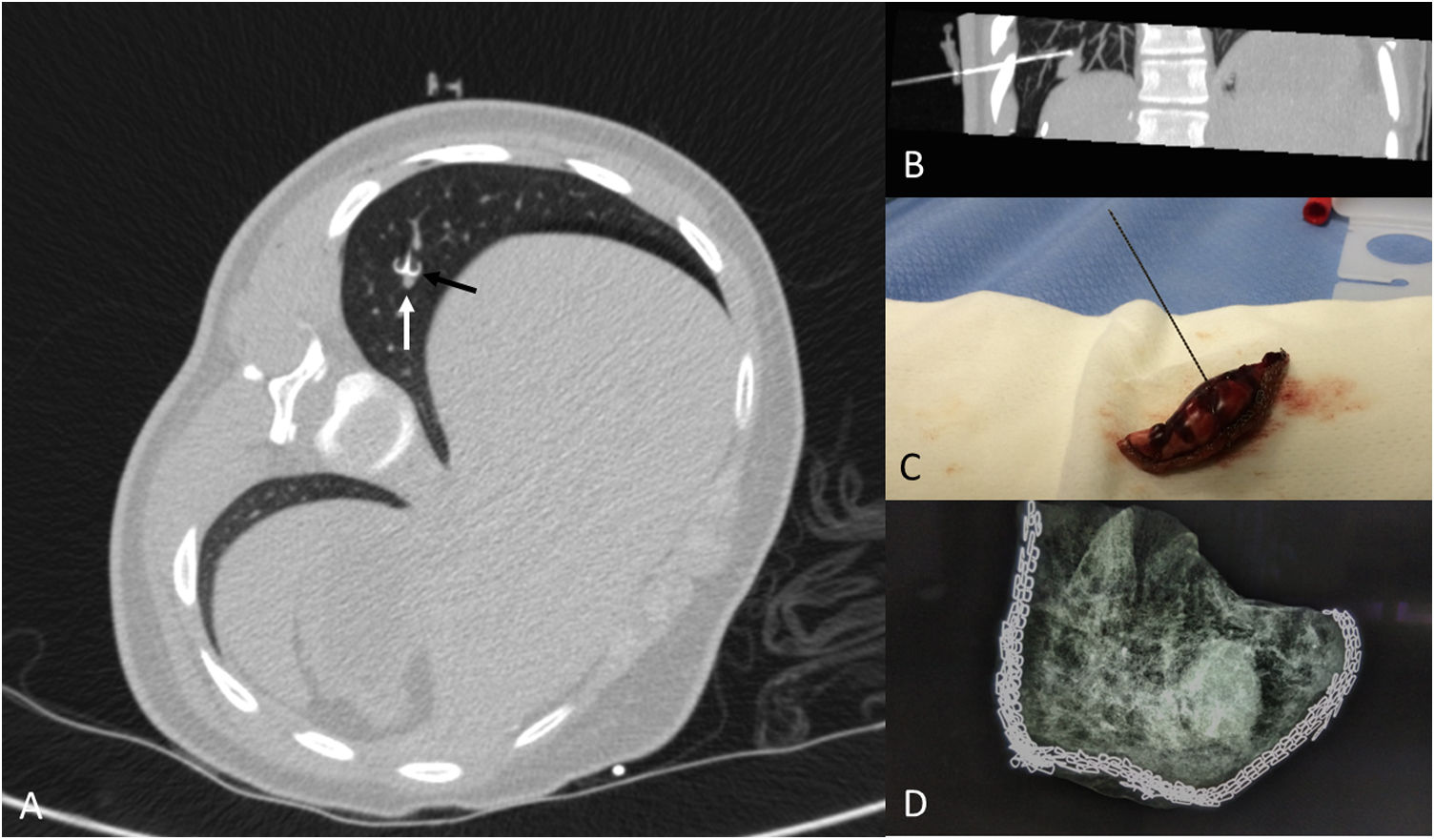

X-ray of the specimen: if there is any doubt as to whether the entire nodule has been resected, the specimen can be X-rayed using a mammography technique. Ultrasound does not tend to be an effective way to detect the pulmonary nodule in the specimen, since in many cases the nodule remains in the centre of the resected specimen, surrounded by air, and therefore is not visible on ultrasound (Fig. 7).

A 15-year-old patient with a history of undifferentiated liver sarcoma. Appearance of a pulmonary nodule at the base of the right lung during treatment, which was positive for undifferentiated sarcoma. A) Localization with hookwire (black arrow) of the nodule (white arrow). B) Oblique parasagittal MIP reconstruction showing the location of the marker in relation to the nodule. C) Atypical segmentectomy specimen. D) X-ray of the specimen using a mammography technique showing the inclusion of the entire nodule.

In the operating theatre, the sterile drapes in which the hookwire comes wrapped are removed and the sterile field will be prepared again.

In all cases, one-lung ventilation will be required:

- •

In patients over six to eight years of age, a double-lumen (26-French or larger) endotracheal tube (ETT) is used.

- •

In younger patients in whom a 26-French ETT does not fit, the following will be considered:

- -

Selective insertion of the ETT in the contralateral lung, with or without prior bronchoscopy.18

- -

Insertion of a balloon catheter (Fogarty catheter) or bronchial blocker in the ipsilateral lung.

- -

- •

In cases in which lung collapse is not desirable, air is insufflated into the hemithorax at an insufflation pressure of 4−6 mmHg.

Positioning of the patient and staff: Gravity is leveraged to improve visualisation, such that the lung segment “hangs” from the hookwire. In addition, it is important to establish an ergonomic workflow that keeps the surgeon, patient and monitor “in line” in that order: in pulmonary nodules, the starting position will be lateral decubitus, with greater posterior inclination (if the nodule is anterior) or anterior inclination (if the nodule is posterior).

Positioning of the surgeon: In general, the surgeon should stand facing the patient’s back if the lesion is more anterior, or facing the patient’s front if the lesion is more posterior.18

In some cases, bilateral thoracoscopy is possible; this technique is reserved for patients who can undergo surgery in the supine position. If it is necessary to mark both hemithoraces but not possible in this position, two procedures are preferable.

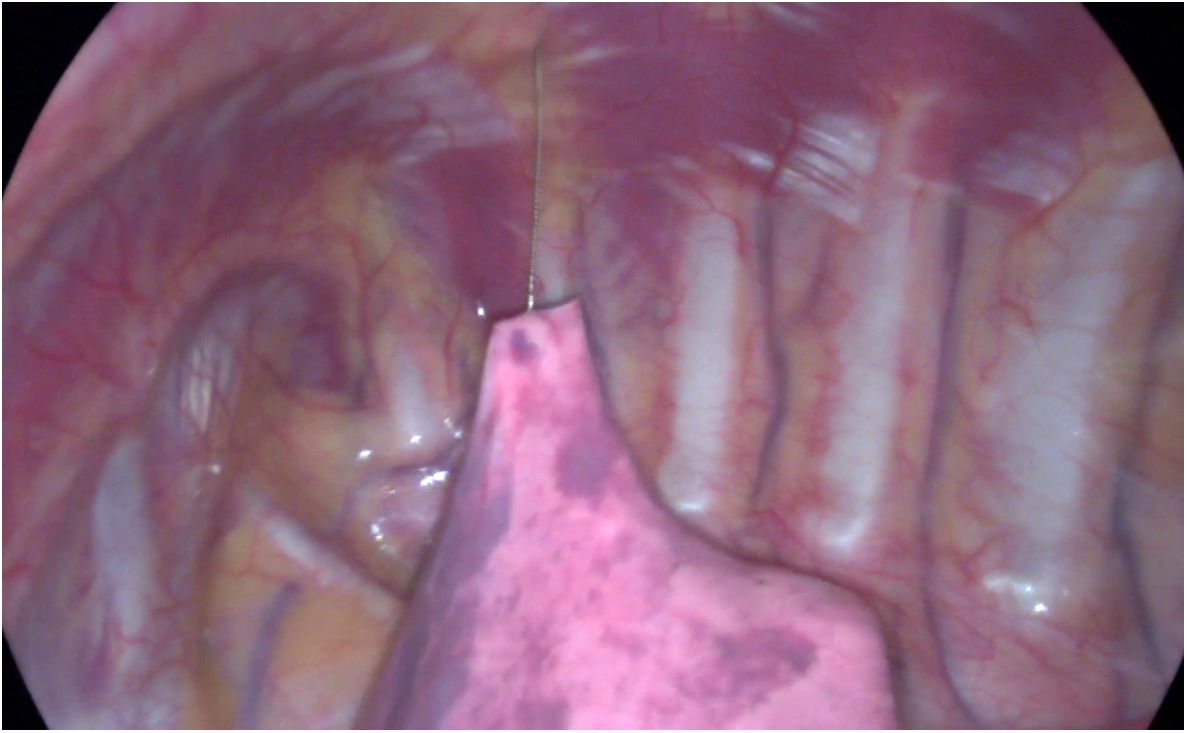

Procedure: Two or three working ports can be used: if the hookwire is well anchored, then the hookwire itself is used to hold the lung and the support trocar is not needed (Fig. 8 and video in Appendix B additional material):

- 1

The first 5-mm trocar for a 30-degree lens is placed on the midaxillary line, in the fifth intercostal space. Through this, CO is insufflated into the pleural cavity at low flow rates (1 lpm) and pressures (4 mmHg) to help slowly collapse the lung and prevent the hookwire from dislodging. It is useful to place the camera trocar as far as possible from the lesion so that it is not in the way of the working trocars.

- 2

The second working port can be a minimal incision, sometimes even without using a trocar, through which a resection instrument (stapler or endoloop) with a diameter of 3 mm is inserted directly in the thoracic cavity. This offers two advantages:

- a)

Greater mobility with an instrument placed directly through the intercostal space, since the trocar between the ribs may impede certain degrees of angulation.

- b)

Economy in using as few cannulae as possible.

- a)

For atypical segmental resection, endoloops or staplers measuring 5 mm are used in patients under 10 kg, and staplers are used in those over 10 kg. Because of its size, the endostapler requires a certain amount of space to be opened; therefore, it is important to place the second port far from the lesion to allow sufficient space to open it. The development of angled staplers has improved the technique to ligate and divide the lung parenchyma in wedge resection.

- 3

The third working port may not be needed if the hookwire is well anchored to the lung parenchyma, or may consist of a support trocar to hold the lung.

Once the segment has been resected, the wire is cut flush with the skin and the specimen is retrieved in an endobag to prevent recurrences at the port site. In general, morcellation of tumour samples is not recommended. For most biopsies, a 10-cm bag is sufficient and can be inserted through the port in which the stapler is also inserted. It is vitally important not to remove an overly large sample through a small port, since there is the concerning possibility of the bag breaking and the sample spilling, which could lead to implantation around the parietal surface of the thoracic cavity or at the port. Therefore, in uncertain cases, the opening through which the specimen is removed must be enlarged.

The biopsy is placed in formaldehyde and sent to radiology to determine whether the nodule has been completely resected in the event of uncertainty or accidental dislodgement, or directly to pathology for histological study (Fig. 7).

Postoperative careA chest tube is left in place, in general through the site of the lowest trocar. Its suction is adjusted to 15−20 cm of water pressure. The other entry sites are closed with absorbable sutures.

The endotracheal tube is reinserted in the trachea or the blocker is removed and the lung is reinsufflated. If there is no evidence of an air leak, the chest tube can be removed and an occlusive bandage applied before the patient is extubated in the operating theatre. If there is a small air leak, the chest tube can be left in place until it has resolved.

Pain is usually suitably managed with intravenous analgesia during the first 12−24 h. The patient begins tolerance on the day of surgery and is discharged as soon as he or she feels comfortable with oral analgesics and tolerates adequate oral intake (48−72 h after surgery).

ComplicationsOf percutaneous localizationThe most common is asymptomatic pneumothorax, which has been reported in 4.3%–50% of procedures.9,13 The onset of symptomatic pneumothorax requiring drainage is very rare.

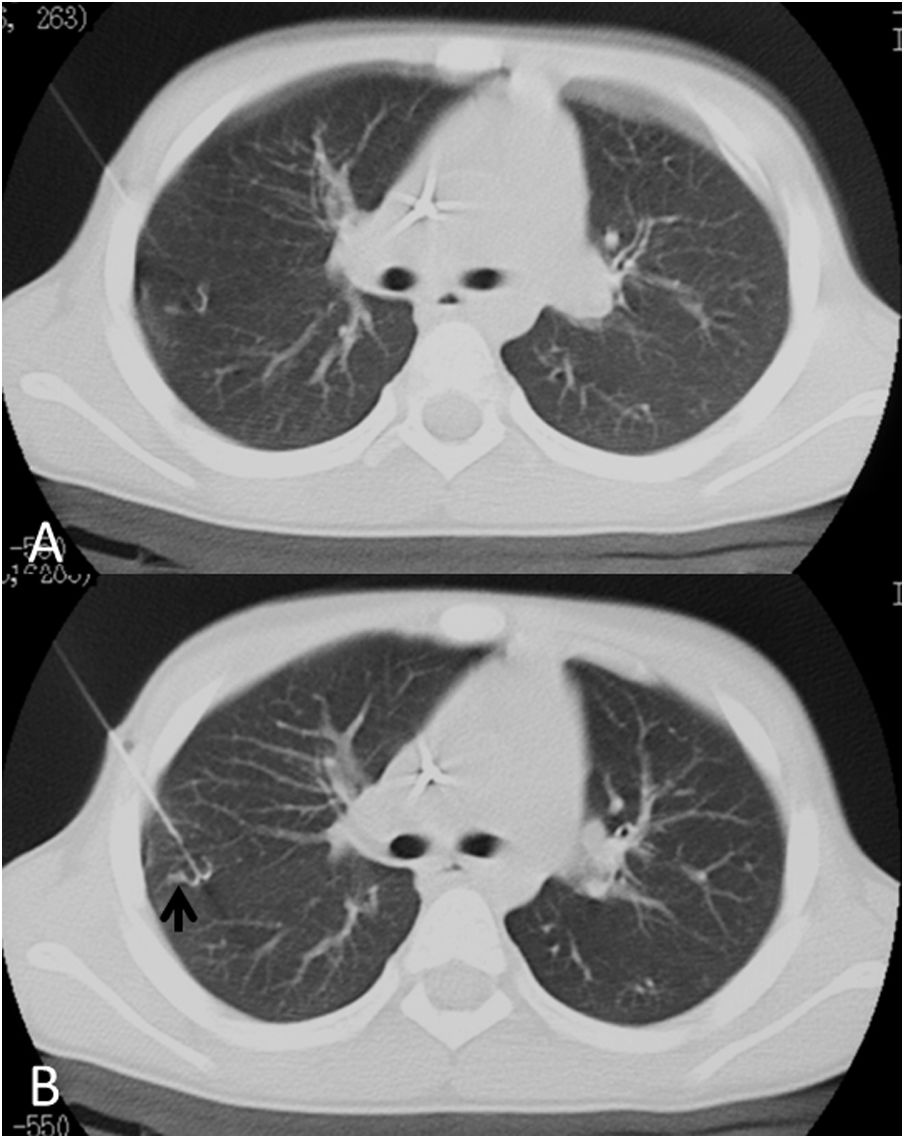

An increase in density can be observed along the trajectory of the hookwire in relation to bleeding, which is also very common; symptomatic bleeding causing significant haemoptysis or pleural haematomas is rare (Fig. 9).

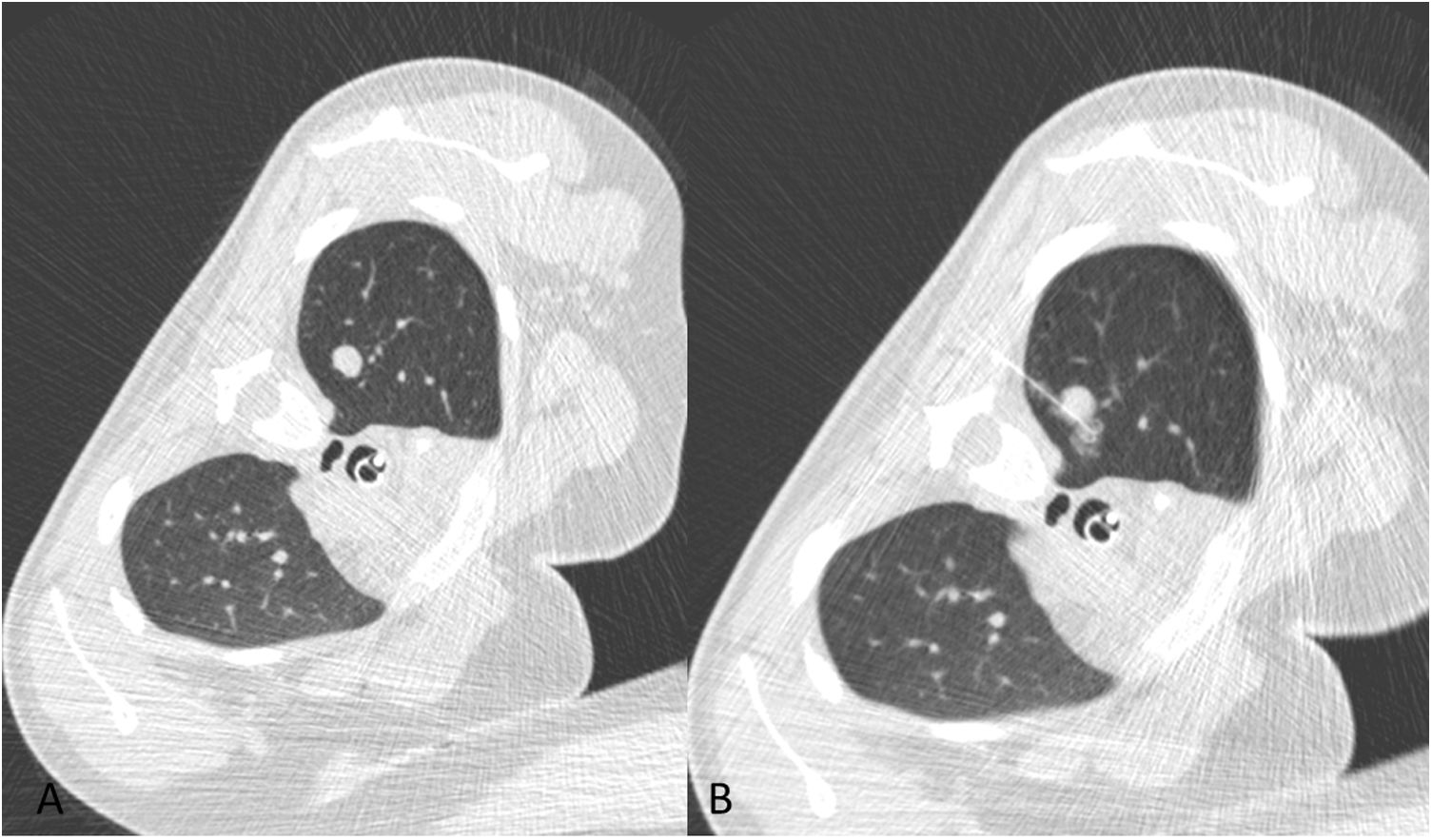

A 16-year-old patient with ischial osteosarcoma and multiple pulmonary nodules, with a result of partially calcified nodules with no evidence of viable disease. A) Non-calcified nodule in left upper lobe. B) Localization with hookwire and appearance of an area of ground-glass opacity in the region of release consistent with slight bleeding.

A failure in hookwire localization may occur due to hookwire dislodgement before or during surgery, with higher rates in children (around 20%) than adults,12 due to the hookwire being advanced more than 4 cm beyond the nodule.

Of thoracoscopyOf surgery: intraoperative bleeding secondary to lung manipulation; injury of intrathoracic structures (rare), including oesophageal perforation, injuries of nerves or major vessels; residual pneumothorax; surgical wound infection; intolerance to the suture material (secondary granuloma); or postoperative chest pain.

In the postoperative period: detachment of staples resulting in a bronchopleural fistula, infection or blood dyscrasia.19

ConclusionThis article describes the pulmonary nodules localization technique and subsequent thoracoscopic resection in paediatric oncology patients and their indications, and it offers some practical considerations to improve the technique.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: CGH.

- 2

Study conception: CGH, MLD, DCR, MRP.

- 3

Study design: CGH, DCR, MRP.

- 4

Data collection: CGH, MLD, DCR, MRP, MCCC.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: CGH, MLD, DCR, MRP, MCC.

- 6

Statistical processing: N/A.

- 7

Literature search: CGH, MCC.

- 8

Drafting of the article: CGH, MLD.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: MLD, DCR, MRP, MCC.

- 10

Approval of the final version: CGH, MLD, DCR, MRP, MCC.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Gallego-Herrero C, López-Díaz M, Coca-Robinot D, Cruz-Conde MC, Rasero-Ponferrada M. Localización de nódulos pulmonares con arpón guiado con TC para resección atípica por toracoscopia en pacientes pediátricos: aspectos prácticos. Radiología. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rx.2021.06.002