Artificial Intelligence has the potential to disrupt the way clinical radiology is practiced globally. However, there are barriers that radiologists should be aware of prior to implementing Artificial Intelligence in daily practice. Barriers include regulatory compliance, ethical issues, data privacy, cybersecurity, AI training bias, and safe integration of AI into routine practice. In this article, we summarize the issues and the impact on clinical radiology.

La inteligencia artificial (IA) ofrece la posibilidad de alterar la práctica de la radiología clínica en todo el mundo. Sin embargo, existen barreras que los radiólogos deben conocer antes de aplicar la inteligencia artificial en la práctica diaria. Las barreras incluyen cuestiones de cumplimiento de la reglamentación, cuestiones éticas, aspectos relacionados con la privacidad de los datos y la ciberseguridad, el sesgo de aprendizaje automático y la integración segura de la IA en la práctica habitual. En este artículo, resumimos estas cuestiones y su repercusión en la radiología clínica.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a fast-growing field in computing and informatics with growing relevance to sub-specialty radiology. There is growing interest to use AI applications in everyday clinical radiology to improve image acquisition, detection, and reporting. AI tools perform more tasks and analyze data better than humans1 and, have the potential to improve patient care by stratifying patient characteristics and disease process to efficiently and non-invasively improve clinical outcomes. AI tools when integrated into daily practice, can free radiologists of repetitive and time-consuming tasks, improving satisfaction and productivity in the workplace.

AI in clinical radiology should be examined from multiple facets including the technical, scientific, professional, economic, and ethical perspectives. There are multiple stakeholders and organizations contributing to the development and integration of AI in practice. Despite the explosion of research related to these techniques, significant hurdles to effective development and safe implementation persist. It is imperative for radiologists to prepare now for active implementation of AI and develop the best solutions to overcome barriers. In this article, we present the current understanding of AI methods and the most significant barriers.

AI in radiologyThe growing interest for integrating AI in radiology practice is primarily driven by the need for greater accuracy and efficiency in delivering patient care. Implementation of AI methods in radiology can enhance the performance of, (a) routine clinical imaging workflow (pre-processing, image acquisition, reporting) and/or (b) image-based tasks (disease detection, characterization, classification, disease response monitoring and integrated diagnostics).2 Computer aided diagnosis (CAD) which encompasses application of computer aided detection (CADe) and computer aided diagnosis (CADx) were among the earliest forms of AI, and have been in clinical radiology practice for many years.3,4 Some examples include applications for breast cancer detection in mammography and lung nodule detection in computed tomography of the thorax.5

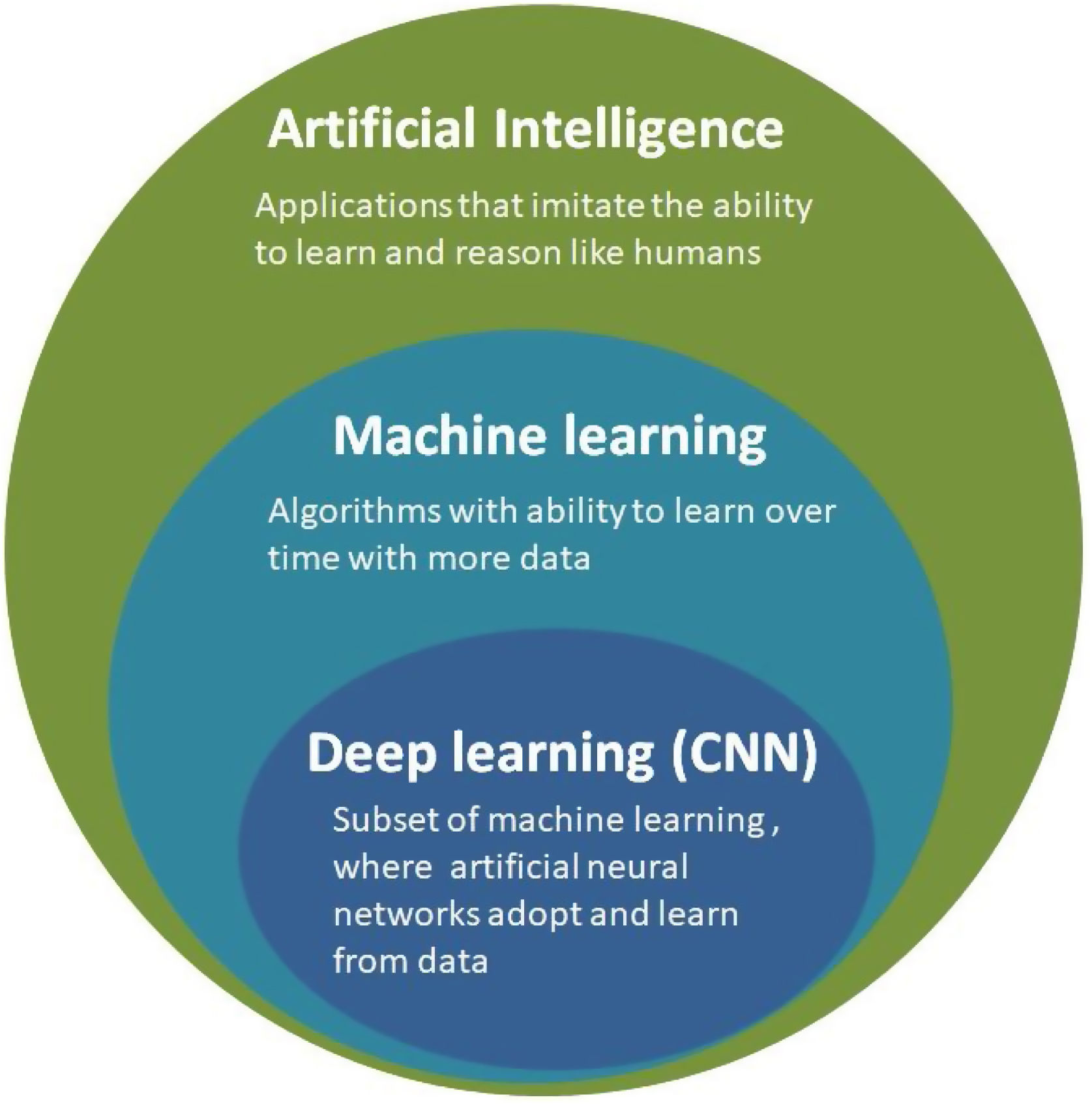

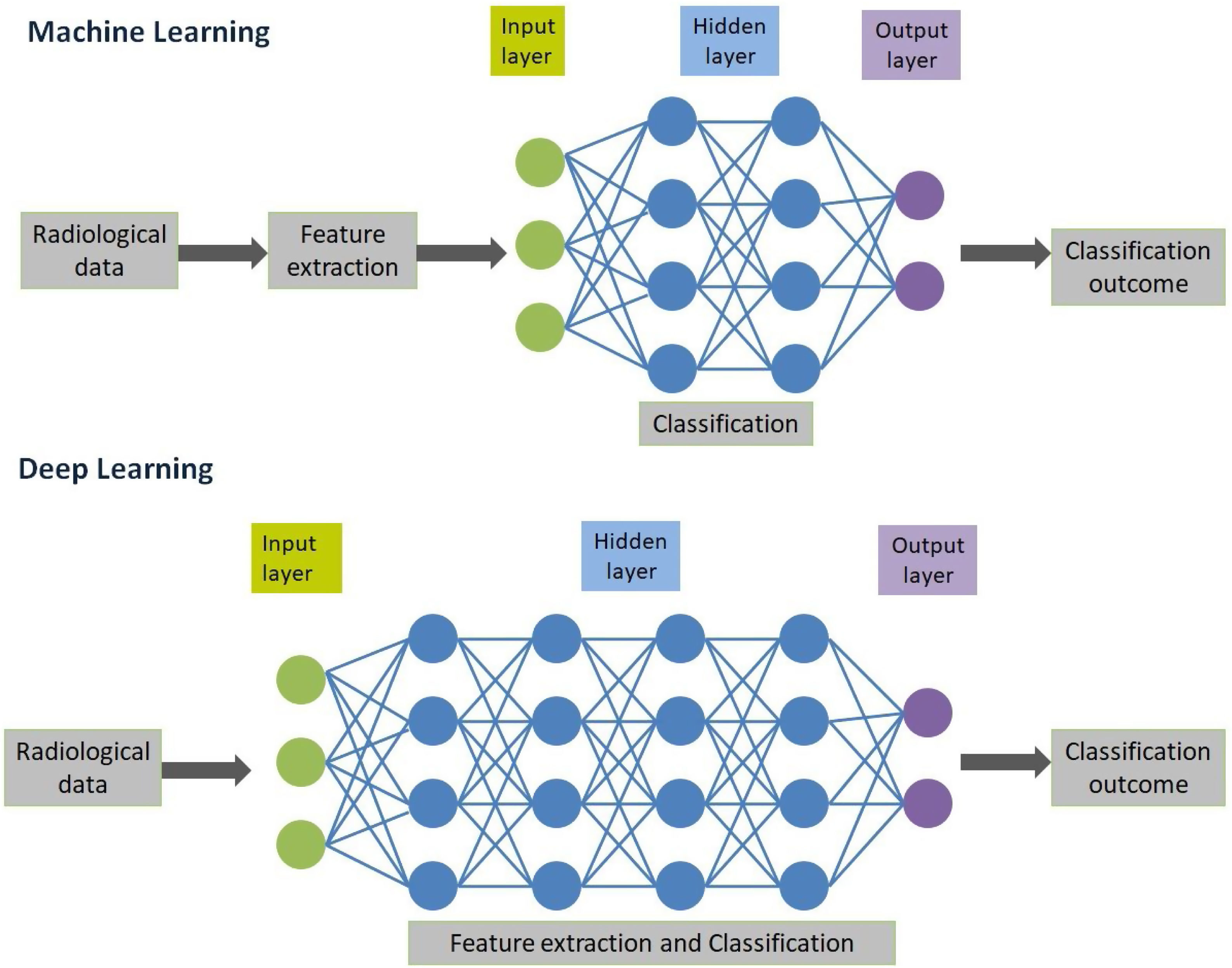

AI in radiology is an umbrella term that encompasses traditional machine learning (ML) and human brain-inspired deep learning algorithms (DL)6 (Fig. 1). Traditional ML involves application of an algorithm to a set of data with some knowledge about these types of pre-trained data, so that this algorithm can be applied to make a prediction. For instance, quantification of radiological characteristics like three dimensional characteristics of tumor, tumoral texture and histogram distribution analysis.7 These models are trained to be used as imaging-based biomarkers in the classification of the patient disease. Recent advances in AI based research have led to the development of DL algorithms that do not rely on explicit pre-defined feature definitions or selection by human experts.8–10 These algorithms are end-to-end defined with a capacity to independently navigate the available dataspace and produce a high value output. Although various DL architecture has been explored to perform different complex tasks, convolutional neural networks (CNN) has been the most prevalent in radiology use today.11 CNN consists of hidden layers that perform series of convolution and pooling operations that extract feature maps and perform feature aggregation, respectively. This is then followed by connected layers that provides high value output before an output layer that can predict the outcome12 (Fig. 2). CNN algorithms have translated more successfully into clinical use compared to traditional ML largely because CNN uses datasets and related meta-data, while traditional ML depends on domain expertise.

Artificial Intelligence is a broader term that encompasses both machine learning and deep learning techniques. Machine learning techniques has been applied since 1980s, while deep learning as a subset of machine learning has been in existence since 2010s due to advancement of artificial neural networks. CNN-Convolutional Neural Network.

The creation of a reliable AI algorithm depends on the robust preparation of data used for training, validation and testing. There are various key steps involved in the process of developing or evaluation of AI solution, which includes, (1) data acquisition at clinical institutions, (2) data de-identification to protect privacy and confidentiality, (3) data curation, involves setting standards and guidelines in the entire process of data preparation pipeline so as to improve the quality of the data. This step is mostly performed by data scientists who have extensive understanding of fundamentals of AI model development, for instance data coding, statistics etc.,13 and are seldom performed by radiologists themselves, (4) data storage and management, (5) data annotation that involves accurate delineation/annotation of images that are needed to train algorithms and finally, (6) model development and clinical integration.

Governance and accountability with the use of AI in healthcareEthical issues and legal liabilityThe ethical issues of AI in healthcare need to be examined through the paradigm of fairness, accountability, and transparency. End-users should be aware of the strengths and weaknesses of AI-based analysis14 and recognize that the kind of data that was used to train the models can have profound implications during clinical application. “Automation bias” is of particular concern and occurs when the radiologist over relies on the AI for clinical decision making, and discounts their own critical judgment.15 The AI may highlight subtle or novel features augmenting a radiologist’s innate ability to detect pathology16; For example, texture-based analysis generates manifold quantitative features that would be imperceptible to even by a very experienced radiologist. Radiologists will need to learn how to integrate this data and recalibrate their own diagnostic thresholds in balance with the added information. It is unclear ethically and legally how the duty of care would be shared between the AI and the radiologist particularly if much of the decision making was automated and invisible to the radiologist. From a legal perspective this could have complications for the radiologist or the AI provider if the fault for substandard care occurred from faulty data or reasoning attributed to the radiologist, AI, or the communication between the two.

Regulatory complianceThe regulatory compliance required for the implementation of AI in practice is complex and varies by country. Although, not all the tasks performed by the AI software comes within the preview of medical device, the USA and EU have their own criteria for identifying healthcare and medical devices.17

In the United States of America (USA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates AI in healthcare under the federal food, drug, and cosmetic act.16 AI-based methods are classified under class 2 medical devices that require 510 (k) notice clearance (Table 1). Although the FDA does not allow for a continuous testing process for an AI algorithm to learn, and therefore the algorithm is frozen once cleared for clinical use.18 There have been proposals from the FDA to implement a regulatory framework for continuously learning AI and machine learning software.19,20

United States Food and Drug Administration regulations related to Artificial Intelligence based devices in radiology.

| Type of AI based device | Clinical application of AI | Regulations |

|---|---|---|

| Computed Aided Diagnosis (CADx) | Aid in diagnosis or classification of disease process | 510 (k) under 21 CFR 892.2060 |

| Computer Aided Detection (CADe) | Direct physician attention to aid identification of potential disease | 510 (k) under 21 CFR 892.2070 |

| Computer Aided Triage and Notification (CADt) | Notification of potential time sensitive findings | 510 (k) under 21 CFR 892.2080 |

| Medical image management and processing system | Applications that provide advanced or complex image processing function | 510 (k) under 21 CFR 892.2050 |

AI, Artificial Intelligence; CFR, Code of federal regulations.

In the European Union (EU), there is no specific binding regulation for the use of AI in healthcare. AI falls within the context of a medical device, with the manufacturer liable to meet all requirements set out for marketing and use of a medical device.21–23 The EU is progressively reformulating legislation with regards to AI in healthcare (General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Cybersecurity directive, and medical device regulation).23

Data ownership, privacy, and intellectual property rightsData in radiology primarily consists of medical diagnostic images of patients, acquired using different imaging modalities. Regulations with respect to data ownership, privacy protection, consent and data-use standards vary by country and sub-sovereign states. In the USA, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) elaborates on the use of sensitive data related to healthcare.24 The HIPAA does not counter the regulations of individual states that have additional protection of patient rights and data use. In the EU, under the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), patients must give explicit consent for the use of their own sensitive or identifiable data.25 In this context, it’s important to note that data ownership and data privacy are not the same, as data ownership does not necessarily indicate that the privacy would be respected by default.26 Depending on the regulations and institutional policies, the rights for accessing data may reside with the institution performing the imaging or the patient may be required to sign informed consent to release data access. These restrictions on data ownership and privacy depend on the part of the world a radiologist is employed, and can inhibit AI-research, limiting and potentially biasing the training, testing and validation of algorithms. Moreover, when the basis of AI software development is for generating profits, consideration should be given to intellectual property rights, and conflict of interest.27

Cybersecurity and data protectionHealthcare is one of the most targeted industries for cyber-attacks and lags behind other leading industries in securing vital data.28,29 With regards to AI, the chances of malware or cyberattack can happen during, (a) data transfer: when large curated datasets are transferred between institutions and companies by either physical or virtual via a network connection, for testing and training purposes, these data contain sensitive information of a large volume of patients and healthcare providers; (b) data storage: researchers have demonstrated that it was possible to use malware to alter Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) data30; (c) data annotation, could become compromised during a cyberattack and the AI algorithm subsequently trained on this data would generate inaccurate results.30 For instance, incorrect marking of boundaries of a tumor would result in inaccurate output, (d) data training: AI algorithms are usually built using open source platforms, and it’s difficult to undertake rectification of these libraries when a vulnerability is detected. Furthermore, CNN has been shown to be susceptible to malicious attacks and, (e) data deidentification: Although, the data for AI training is anonymized to preserve privacy and confidentiality, it’s been shown that metadata from DICOM or facial recognition software27 can be used to re-identify a patient.

Thus, the process of developing and implementing AI systems should include regular audit, strong security controls (such as encryption), multifactor authentication, network security, firewall etc.30 Recently, the process of development operations/development security operations that involves the process of integration of cybersecurity earlier in software development phase resulting in an in-built software security has shown greater resilience in thwarting cyberattack.31 Another innovative technique is the development of federated learning,32 where AI models can be trained locally in hospitals or institutions, instead of collecting data from different institutions and storing them centrally thereby avoiding the implications arising out of data transfer between the institutions.

Conflicts of interestRadiologists working on AI research and development may have financial affiliations with software developers which place them in a conflict of interest. Most conspicuously, this occurs when an institution decides on the purchase of AI software from the developer, and the radiologist owing to their affiliation may be more inclined towards purchasing AI software from the same company. Such conflicts should be prevented or minimized through transparent public disclosure, conflict of interest disclosure policies, and abstaining from commercial decisions where a real or perceived conflict of interest may arise.33,34

Training for AI development and training with AIData variability and unbiased training dataThe performance of AI depends on the datasets that are used for training and testing. The data is usually acquired and trained from a single institution, with the expectation that the outcome of these trained data is generalizable to other institutions around the globe. The generalization of datasets can only happen with a large unbiased sample size that is representative of diverse populations and diversity of human diseases. Acquisition of such a large sample size of de-identified, curated, stored and annotated datasets requires wide collaborations among academic institutions, commercial entities, and radiological societies.35,36 There has been progress in these lines with the initiatives from various radiology advocacy groups and public repositories like the Radiological Society of North America’s Radiology Informatics Committee,37 the European Society of radiology AI blog,38 the American College of Roentgenology Center for Data Sciences,39 and The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA).40

AI methods are yet to see widespread clinical adoption of due to concerns arising due to limited generalization performance. These are contributed in part due to diverse range of imaging devices, techniques, protocols and patient population. Data harmonization is a new paradigm which ensures that the confounding variations in datasets are “harmonized” to a common reference domain.41 This would enable the widespread adoption and standardization of DL methods with good generalization properties.

Impact of AI on inherent disease detection skillsThe accuracy of disease detection and characterization in radiological images depends on pattern recognition skills acquired through years of clinical reporting experience. AI provides qualitative and quantitative data depending on ML or DL algorithm that may be undetected with human eyes.38 When a learner (radiologist in training) uses the AI for disease detection and characterization, interpretation time and the intensity of perceptive and integrative skill to the tasks may be reduced. Depriving the learner of the opportunity to develop and improve core diagnostic skills.

AI in curriculumThe practicing radiologist will need to have a basic understanding of the validation and performance of the algorithms. It will be necessary to have the resources for training, user-adaptation, practice deployment and potential co-creation.42 These will require enhancements in the current curriculum for radiologists-in-training. Development of this type of training enhancement is already being developed in the USA by the National Imaging Informatics Curriculum and Course.43 While in Europe, the European training curriculum,44 in level 1 and 2 includes understanding functioning and application of AI tools, also the knowledge related to ethics of AI, performance assessment and critical appraisal. Furthermore, European society of Medical Imaging Informatics (EuSoMII),45 an institutional member of ESR, conducts training activities on AI.

AI workflow integration into radiology practiceRadiomics and un-seen inferences on clinical decision makingRadiomic analysis involves automated extraction of clinically relevant information from radiologic images and to probe its relevance as novel biomarkers in routine clinical practice.46,47 Radiomic biomarkers is entirely data driven, while the traditional biomarkers are developed in the context of a biological hypothesis. Thus, the radiomic signatures would need more stringent validation, including comparison to existing reference standards for it to be adopted for reporting guidelines and evaluation standards.

The degree of subjectivity and variability among the radiologist readers can be reduced with the use of AI quantitative imaging methods, where quantitative voxel imaging features are associated with clinical disease classifications and outcomes. However, the rate-limiting factor in such a scenario would be that not all radiomic features would be relevant and rational. This would require the expertise of the radiologist to make a conclusion that combines both the clinical picture and radiomic analysis to determine the disease management. Traditional pre-defined ML based algorithms identify conspicuous objects within the images, and these clinical images are then curated and segmented to generate optimal outputs. These outputs are then assessed by radiologists to decide if they merit further attention, making the radiology workflow more labor intensive.

Accuracy of pre-defined traditional ML and DL algorithmsErrors that occur during training get propagated and potentially magnified when performing image-based tasks in daily radiology practice. Some pre-determined disease detection tasks will fail to generalize across different images. For instance, CADx systems that are designed with pre-defined criterion for detecting solid lung nodules are unable to flag rare presentation of suspicious nodules such as ground glass nodules or cavitary nodules.48 On the other hand, CNN based CADx systems can learn from the diversity of disease processes and diverse patient populations, to overcome the limitations posed by pre-defined machine learning algorithms.

Integration of AI into practice systemsAI tools that have the regulatory clearance to be implemented in daily practice, will need to be integrated with hospital information system (HIS), picture archiving and communication system (PACS) to give a seamless user experience. To fundamentally add value for radiologists in daily practice, these AI tools should demonstrate reliability, speed, and accuracy to improve patient outcomes.

Imaging of cancer includes multiple modalities used independently or in-combination, including radiography, ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) or positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging (PET-MRI). Irrespective of the modality used there should be shared representation of AI features between the modalities for assessment of tumor characteristics using ML or DL based algorithms. ML and DL software’s must undergo a thorough quality control check, to detect their response related to misregistration, motion artifact, multimodality adaptability to signal-to-noise characteristics and other potential bias, as these errors can compromise image analysis and propagate through the radiology workflow with an adverse impact on the clinical outcome.

Transformation of radiology workIt is undeniable that machines and software have made some traditional jobs particularly redundant49 and radiologists’ workflow is bound to change in this era of AI. AI-radiologist collaborations are proving to have a better performance than either one alone in clinical practice.50,51 The notion of AI replacing radiologist is illusory, and the most likely possibility is that radiologist who embraces and adapts AI into radiology practice will replace radiologists who don’t.52

Resource inequality across the continentsDue to resource and financial constraints to acquire AI resources, some parts of the society may be denied the potential benefits of patient care offered by AI-based radiology. In the future, if there is inclusion of AI into reporting schemes to improve the clinical decision process and patient management, this may create a clear demarcation in the expected lines of patient care.53,54 To address this resource inequality, there must be incentives and philanthropic measures to aid software purchases in low-income countries where the national healthcare budget is grossly under-funded.

Future perspectives and conclusionAI methods are increasingly stepping out of research and training domains towards active integration within daily clinical radiology practice. AI methods have become more sophisticated, and algorithms have evolved over time, from pre-trained or end-to-end trained to unsupervised learning tasks that are able to perform complex analysis with the potential to efficiently deal with diversity in datasets. Research continues to show an undisputed need for active integration of AI in radiology practice to improve clinical decision processes and patient outcomes.

Machine-based learning software and AI in radiology has an enormous potential to benefit patient care, despite the barriers that have been examined in this article. AI software are often commercially driven and may promise more, while underplaying its inherent weaknesses. By collaborating with researchers and evaluating the AI solutions before deployment, radiologists can ensure a safe and meaningful integration of AI solutions into clinical practice. Contrary to the forecast of being replaced by an AI, most radiologists who embrace this technology, ensure its effectiveness and integration into training of the next generation of radiologists will see benefits to patients and their profession. The scope, accuracy and efficiency of practicing radiologists is expected to expand, not contract when enabled by powerful AI tools. The authors believe that it is the responsibility of all radiologists to be aware of the potential benefits of AI, to see and diminish barriers to safe and proven-effective AI technology. The benefits of patients, and society, balancing costs, and access equity must be part of the conversation to ensure these powerful new technologies reach their potential.

- 1

Radiologists should be aware of the inherent strengths and bias in creating, deploying, and using AI tools in their daily clinical practice.

- 2

Clinical deployment of AI tools requires correct navigation of regulatory and data protection policies.

- 3

Educational resources for practicing radiologists and trainees are needed to facilitate the safe and effective use of AI tools in clinical radiology.

Authors have not received any funding for this article

Research involving human participants and/or animals: This article is not a research on animals and no human participants were enrolled.

Informed consent: Informed consent was waived by IRB (Institutional Review Board) for this review article.

AuthorshipGuarantors of integrity of the article, article concept, design, manuscript drafting A.N.

Revision for important intellectual content all authors.

Manuscript editing A.J.,P.S., S.R., B.M., A.N.

Literature re-search, P.S., S.R., B.M., A.N.

Final version of manuscript is approved by all authors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Please cite this article as: Nair AV, Ramanathan S, Sathiadoss P, Jajodia A, Blair Macdonald D, Dificultades en la implantación de la inteligencia artificial en la práctica radiológica: lo que el radiólogo necesita saber, Radiología. 2022;64:324–332.