Aortic dissection (AD) is the most common acute condition of the aorta and has a high mortality. Therefore, it is a radiological emergency of vital importance. Currently, five subtypes are distinguished, among which AD class 3 – also known as limited or subtle AD- is the less recognised. This type of dissection is infrequent and needs to be acknowledged radiologically in order not to go unnoticed. Regarding its imaging features, this entity is characterized by a small focal bulging of the aortic wall outline and/or a limited round dilation at the region affected by the intimal tear. Recently, the low familiarity of the radiologist with this condition has been emphasized. With the aim of illustrating the main imaging findings of this entity and reviewing its most relevant aspects, we present four cases of AD class 3 diagnosed in our hospital.

La disección aórtica es la patología aguda más frecuente de la aorta y presenta una elevada mortalidad, por lo que constituye una urgencia radiológica de vital importancia. Actualmente se diferencian cinco subtipos, siendo la clase 3, también conocida como disección aórtica limitada o sutil, la variante más desconocida. Este tipo de disección es infrecuente y exige un conocimiento claro de su semiología radiológica para que no pase desapercibida. Desde el punto de vista de la imagen, esta entidad se caracteriza por un pequeño abultamiento focal del contorno aórtico y/o dilatación circunferencial localizada del segmento aórtico afectado por el desgarro intimal. Recientemente se ha destacado la baja familiaridad del radiólogo con esta patología. Con la finalidad de ilustrar los principales hallazgos de imagen y revisar los aspectos más relevantes de esta entidad, presentamos cuatro casos de disección aórtica de clase 3 diagnosticados en nuestro hospital.

Aortic dissection is the most common acute pathology of the aorta that often has a fatal outcome,1 and is therefore a vitally important radiological emergency. The guidelines of the European and American cardiology societies currently include five subtypes2,3: classical dissection with intimal flap (class 1); dissection with intramural haematoma (class 2); limited intimal tear (class 3); penetrating aortic ulcer (class 4); and iatrogenic or traumatic dissection (class 5). Class 3 aortic dissection, the rarest form, is also known as incomplete tear, or limited, subtle or discrete dissection.2–8 Despite being a recognised entity, recent evidence has shown the extent to which radiologists and other clinicians are unfamiliar with this aortic pathology, largely because it is so difficult to diagnose.7

According to the largest series published to date,7 this type of aortic dissection is uncommon (4.8 %) and can easily be overlooked unless the radiologist is fully acquainted with its imaging features. In order to illustrate the main imaging findings and review the most relevant aspects of this pathology, we present four cases of class 3 aortic dissection diagnosed in our hospital.

Description of the casesPatient 1: A 52-year-old man, obese, smoker, with hypertension, presented at the emergency department with central lancing thoracic pain irradiated to the back, associated with vagal reaction that does not respond to administration of vasodilators. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) on arrival was 200 mmHg. An electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed that showed atrial fibrillation at 70–80 bpm, with no other disturbances of note. The blood test was normal.

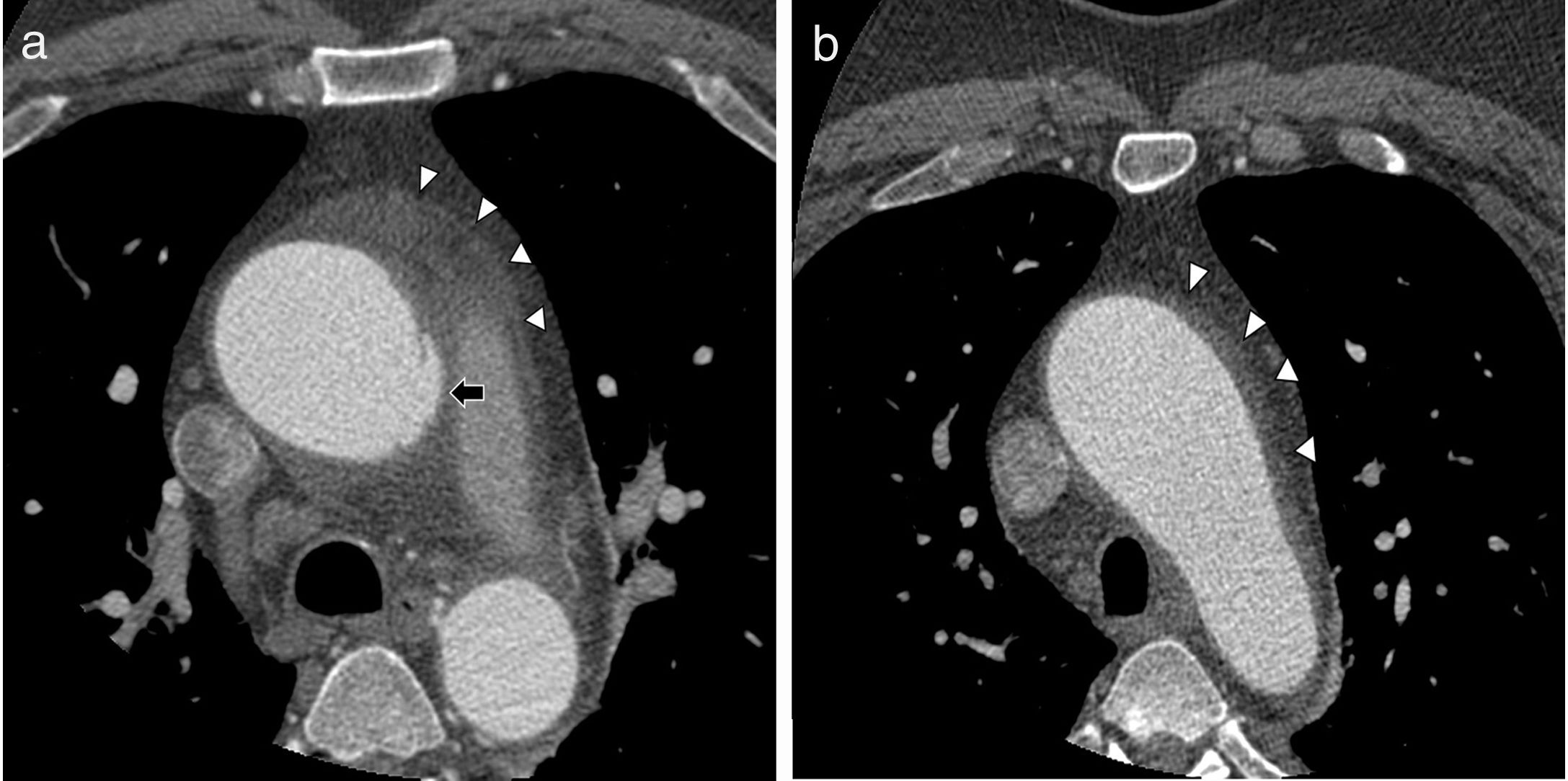

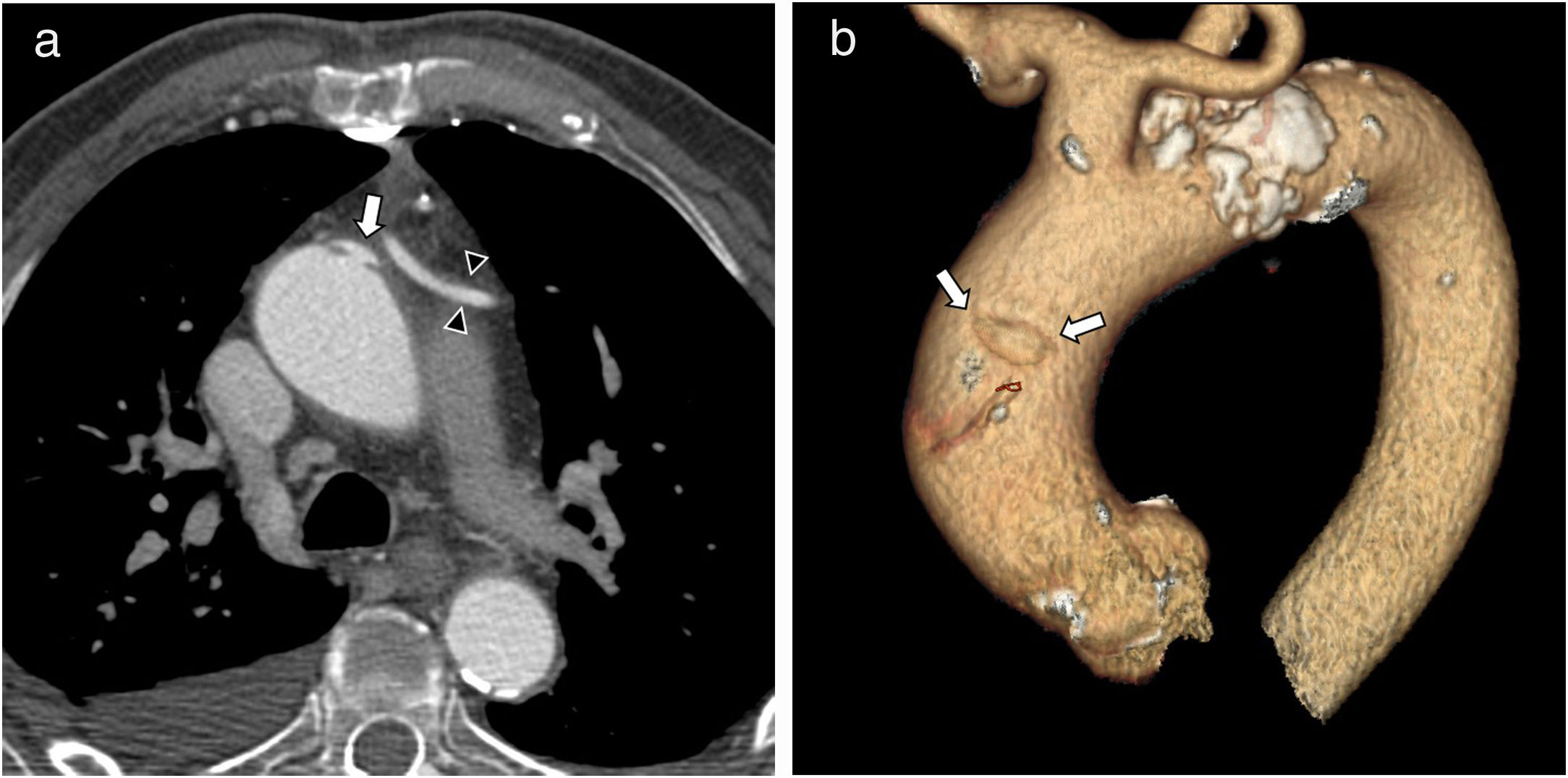

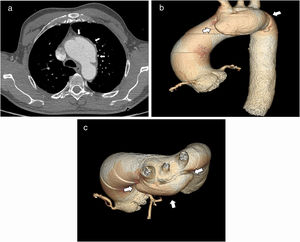

Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the aorta was performed, which showed dilation of the proximal ascending aorta or aortic arch, with questionable irregularity of the vessel wall, which was initially interpreted as “possible artefact”. The patient was admitted to the Cardiology Department, where his symptoms improved. A new CT angiography was performed 24 h later, this time ECG-synchronised, which more clearly showed a bulge in the left lateral wall of the ascending aorta with a “mushroom cap” sign and fluid infiltration of adjacent mediastinal fat (Fig. 1A and B). These findings were interpreted as a small fissure. In view of the patient’s improved status, he was discharged home.

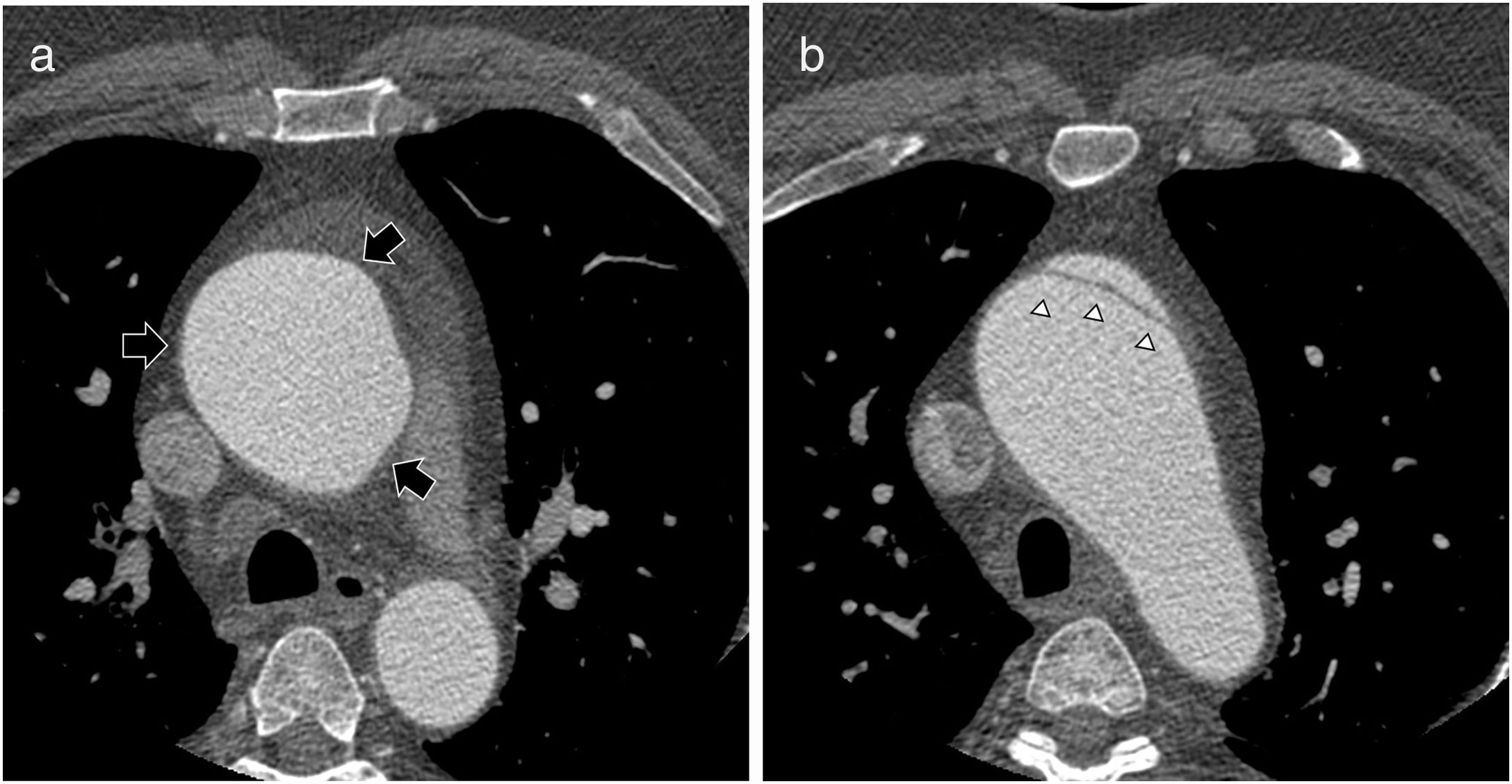

One month later, a follow-up CT angiography scan was performed which showed considerably increased dilation of the ascending aorta and a clear Stanford type A aortic dissection (Fig. 2A and B). Given these findings, we decided to perform emergency surgery, consisting of implantation of a valved conduit and replacement of the aortic arch and brachiocephalic trunk. The patient made good progress after surgery, and follow-up studies have so far been normal.

Thoracic aortic ECG-synchronised CT angiography. A) Axial image at the same level as in Fig. 1A. Segmental circumferential dilation of the ascending aorta at the level of the bulge described in Fig. 1A (arrow). B) Axial image at the same level as in Fig. 1B. Classic Stanford type A dissection with intimal flap (arrowheads).

After performing a literature review, we subsequently concluded that the case corresponded to a class 3 aortic dissection.

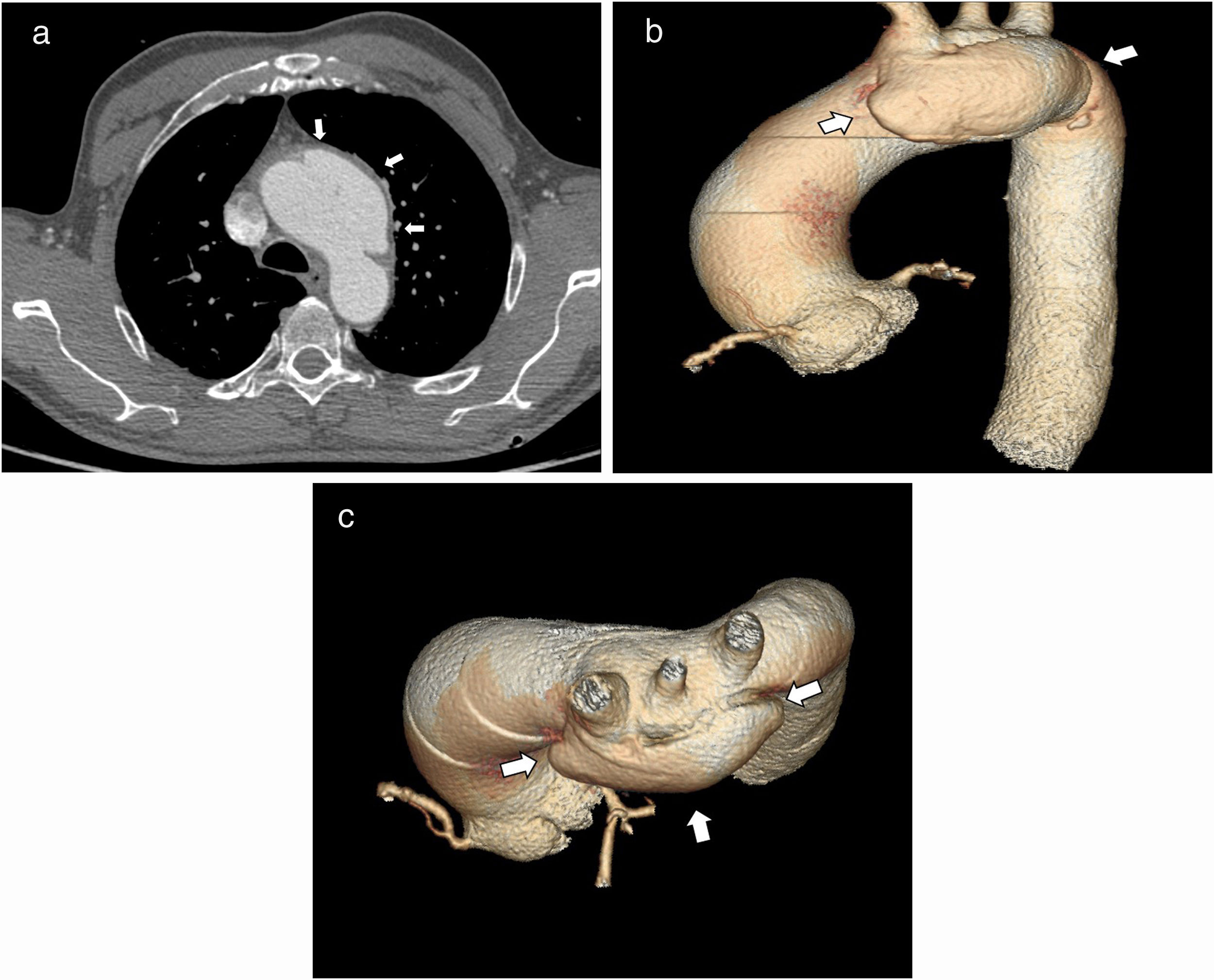

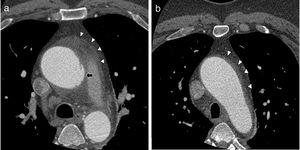

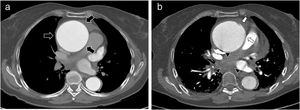

Patient 2: A 63-year-old man with various cardiovascular risk factors and symptomatic sinus bradycardia, who was referred to the Cardiology Department by his primary care physician for a three-month history of weight loss, dizziness and syncope, intermittent headache and episodes of haemoptysis. An echocardiogram was performed, which showed an increase in the diameter of the aortic arch and ascending aorta, with “possible intramural haematoma, with no clear evidence of dissection”. The patient was referred to the hospital emergency department to rule out dissection. A CT angiography was performed, which showed a large saccular aneurysm arising from the left anterolateral wall of the aortic arch, with “mushroom cap” morphology. In conclusion, the diagnosis was probably “intimal tear or limited dissection (class 3) Stanford type A, with secondary saccular aortic dilation” (Fig. 3A–C).

Thoracic aortic CT angiography without ECG synchronisation. A) Large saccular bulge arising from the left anterolateral wall of the aortic arch, with a “mushroom cap” appearance (arrows), and fluid infiltration of mediastinal fat. 3D volume rendering, oblique lateral (B) and cranial (C) view. The “mushroom cap” morphology of class 3 dissection (arrows) can be seen more clearly.

The patient was referred to cardiovascular surgery, where the dissection was repaired by resection of the ascending aorta and reconstruction using a hybrid prosthesis. The initial postoperative period was favourable, but on the 6th postoperative day he developed a mesenteric arterial embolism, so an emergency laparotomy was performed with intestinal resection of the necrotic segments. Since then, he has made good progress, and is currently asymptomatic.

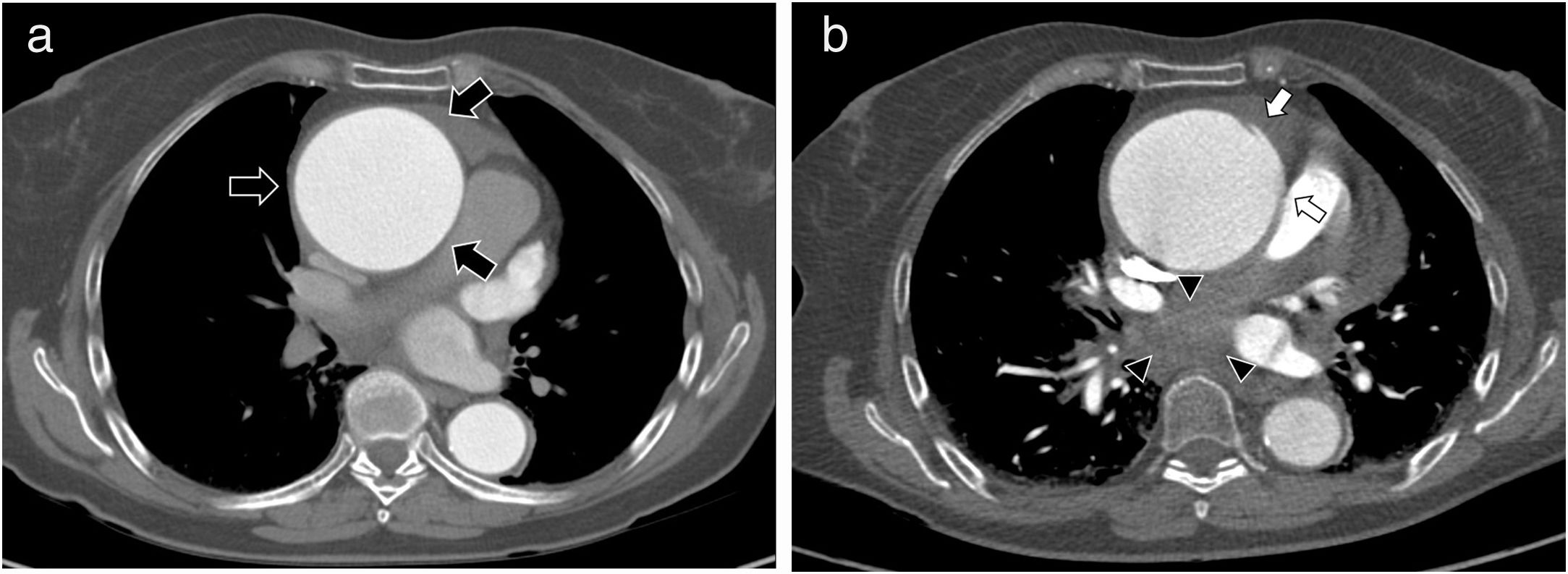

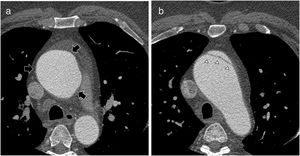

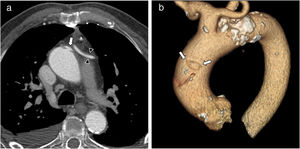

Patient 3: A 71-year-old woman with a cardiac ultrasound diagnosis of ascending aortic aneurysm, which in the latest computed tomography (CT) follow-up had reached 7 cm maximum diameter (Fig. 4A). One month after this CT scan, the patient presented with oppressive centrothoracic pain of increasing intensity irradiating to the jaw and back, with SBP of 200 mmHg, so she was referred to the emergency department by her primary care physician. Acute aortic syndrome was suspected, so a CT angiography scan of the aorta was performed, which showed limited dissection in the anterolateral wall of the ascending aorta that was not present in the previous CT (Fig. 4B). A small associated intramural haematoma and an acute mediastinal haematoma were also noted.

Thoracic aortic CT angiography without ECG synchronisation. A) Ascending aortic aneurysm measuring approximately 7 cm in diameter (arrows). B) Thoracic aortic CT angiography without ECG synchronisation performed one month later. Small bulge, not previously seen, arising from the left lateral wall of the aortic aneurysm (arrows). Acute mediastinal haematoma causing compression of the pulmonary artery (arrowheads).

Emerging supracoronary tube graft was performed to replace the ascending aorta. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient made good progress. Postoperative follow-up tests and echocardiogram confirmed the absence of complications, so she was discharged home. She is currently asymptomatic.

Patient 4: An 81-year-old man diagnosed with severe three-vessel disease and left main coronary artery stenosis who underwent scheduled myocardial revascularisation in the Vascular Surgery Department. The procedure was uneventful, and given the patient’s good postoperative progress, once the complementary tests showed that he was clinically and haemodynamically stable, he was discharged home.

One month later, the patient presented at the Emergency Department with a two-day history of centrothoracic pain and dyspnoea on minimal effort. Given the suspicion of postoperative complications, he was admitted for examination. Cardiac catheterisation performed during admission showed a saccular defect in the ascending aorta, suggestive of a penetrating ulcer, although this diagnosis was not confirmed on complementary CT angiography. However, given the persistence of the symptoms and the mismatch between the imaging tests, we decided to transfer the patient to our hospital’s Cardiovascular Surgery Department, where another CT angiography was performed. This examination confirmed the lesion observed on cardiac ultrasound, although it was classified as a class 3 dissection (Fig. 5A–C).

Thoracic aortic CT angiography without ECG synchronisation. A) Small bulge arising from the left anterolateral wall of the ascending aortic arch-aorta with “mushroom cap” appearance (arrow). Note the aortocoronary bypass graft (arrowheads). B) 3D volume rendering, oblique lateral view. The bulge typical of class 3 dissection (arrows) is clearly seen.

Given the impossibility of percutaneous treatment and the high surgical risk of the patient, a conservative approach and medical treatment were decided. The patient remained stable and event-free during his stay, so he was eventually discharged home.

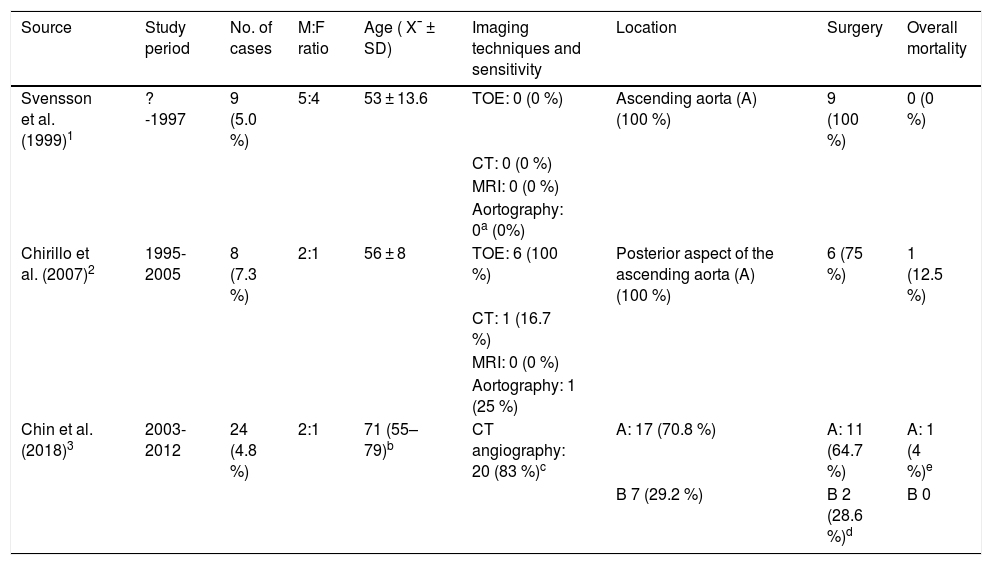

DiscussionIn 1999, Svensson et al. described nine cases of aortic dissection that went unnoticed in various imaging tests.5 In retrospect, the authors observed an eccentric ascending aortic bulge on the images, which they decided to classify as a “class 3” dissection, to differentiate it from the classic intimal flap and intramural haematoma-type dissections. Since then, with the exception of a few isolated cases (e.g. those reported by Elefteriades et al.9), only three series of cases reporting this pathology have been published (Table 1).

Characteristics of the series published on class 3 aortic dissection.

| Source | Study period | No. of cases | M:F ratio | Age ( X¯ ± SD) | Imaging techniques and sensitivity | Location | Surgery | Overall mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Svensson et al. (1999)1 | ?-1997 | 9 (5.0 %) | 5:4 | 53 ± 13.6 | TOE: 0 (0 %) | Ascending aorta (A) (100 %) | 9 (100 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| CT: 0 (0 %) | ||||||||

| MRI: 0 (0 %) | ||||||||

| Aortography: 0a (0%) | ||||||||

| Chirillo et al. (2007)2 | 1995-2005 | 8 (7.3 %) | 2:1 | 56 ± 8 | TOE: 6 (100 %) | Posterior aspect of the ascending aorta (A) (100 %) | 6 (75 %) | 1 (12.5 %) |

| CT: 1 (16.7 %) | ||||||||

| MRI: 0 (0 %) | ||||||||

| Aortography: 1 (25 %) | ||||||||

| Chin et al. (2018)3 | 2003-2012 | 24 (4.8 %) | 2:1 | 71 (55–79)b | CT angiography: 20 (83 %)c | A: 17 (70.8 %) | A: 11 (64.7 %) | A: 1 (4 %)e |

| B 7 (29.2 %) | B 2 (28.6 %)d | B 0 |

CT angiography: computed tomography angiography; CT: computed tomography; F: female; M: male; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; SD: standard deviation; TOE: transoesophageal echocardiography.

From an anatomical point of view, class 3 dissection consists of a partial stellate or linear tear through the intima and underlying superficial media that results in exposure of the middle layer and/or adventitia to the vessel lumen. However, unlike classic dissection, there is no significant separation of the tunica media, nor any false lumen. In summary, it is an intimal tear without flap that produces a focal bulge in the aorta.4–7 In other cases, a longitudinal intimal tear can cause localised dilation of the affected aortic segment. Although the pathophysiology of this entity remains unclear, a number of case reports have corroborated the hypothesis proposed by Svensson,5 i.e. that the (initially) limited dissection can evolve to a complete dissection4,6 (see case 1 of our series). This observation supports the existence of a common pathophysiological mechanism that involves a focal weakness of the aortic wall which allows for progressive disruption. In this sense, the anatomopathological study of surgical pieces has basically shown two patterns: degeneration/cystic necrosis of the media (loss and destruction of tunica media elastin with loss of smooth muscle tissue) and atherosclerosis (intimal hyperplasia, fatty deposits and calcifications),6 with the former being more common.7

In terms of anatomical location, all the dissections in our series occurred in the left anterolateral wall of the ascending aorta and, therefore, correspond to type A dissections according to the Stanford classification. In two of the other three series published, all dissections were also type A, although Chin et al. reported a frequency of just 70.8 % (Table 1).

On CT, class A dissection typically presents as a small focal bulge of the aorta and/or localised circumferential dilation of the aortic segment affected by the intimal tear. Three of the four cases in our series showed a small focal bulge. However, in case 2, the bulge was large. Class 3 dissection may occasionally be associated with intramural haematoma,5–7 a finding present in case 3. In case 1, the CT scan performed one month after the first study showed that the small intimal tear had progressed to dissection. Previously unseen dilation of the aortic circumference at the level of the tear was also observed. This is the other typical sign of class 3 dissection.

These dissections, because of their morphology, are usually described as “mushroom cap” lesions, or stretch marks.10 In our series, all cases showed the “mushroom cap” sign.

Although this type of tear can also be diagnosed using transoesophageal echocardiography, aortography and magnetic resonance imaging, ECG-synchronised CT angiography, which eliminates aortic pulsation artefacts, is currently the study of choice.11 This technique can have a sensitivity of over 95 %, although this will depend on the radiologist’s familiarity with the entity and the use of ECG-synchronisation. In most cases, however, diagnosis can be made without the latter, and postprocessing with 3D volume rendering7 is particularly useful. In our series, diagnosis was made without the use of ECG synchronisation in cases 2, 3 and 4. The main limiting factor in the detection of class 3 dissection is not the CT technique itself, but the radiologist’s familiarity with this entity.7,10 In fact, surgical treatment was delayed one month in case 1 of our series because both the radiologists and cardiovascular surgeons in our hospital were unfamiliar with class 3 aortic dissection.

Although this type of dissection is rare, when dealing with patients with chest pain, radiologists should bear it in mind and carry out a detailed examination of the images to detect subtle defects.11 In class 3 dissection, the only layer covering the aortic lumen is extremely thin, and thus is prone to rupture, allowing fluid to seep through it to the pericardium.5 For this reason, we, like other authors,7,10 consider that patients with this type of dissection should receive the same treatment usually given for classical dissection or intramural haematoma.

ConclusionsClass 3 aortic dissection is an uncommon, potentially fatal, entity. CT angiography has high sensitivity for the detection of this entity, particularly when performed with ECG synchronisation. The findings, though subtle, are quite specific, and consist primarily of a limited focal or circumferential bulge of the aortic lumen, with no intimal flap. The main diagnostic limitation is the radiologist’s familiarity with this condition. Although more evidence is needed, most authors recommend treating this variant in the same way as a classical dissection, depending on the affected area and the patient’s risk stratification.

FundingNo funding was received for the conduct of this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz Carazo E, Láinez Ramos-Bossini AJ, Pérez García C, López Milena G. Disección aórtica de clase 3: una entidad poco conocida. Presentación de 4 casos. Radiología. 2020;62:78–84.