Retinoblastoma (RB) is the most common pediatric ocular malignancy and causes high mortality if left untreated. An accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment are of utmost importance, leading to optimal clinical outcomes. RB treatment has evolved over the years with a paradigm shift from life-saving enucleation to globe- and vision-sparing strategies. Intra-arterial chemotherapy (IAC) has become an essential and effective pillar in the management of RB. It has gained popularity as it is a targeted chemotherapeutic agent infusion technique achieved via superselective ophthalmic artery (OA) catheterisation. This improves tumour treatment and reduces recurrence and systemic side effects. In addition, it is often performed as an outpatient procedure, reducing the need for prolonged hospital stays and improving the overall patient experience. In this review, we discuss the history of IAC as well as its technical evolution, outcomes, potential complications and limitations.

El retinoblastoma (RB) es la neoplasia ocular pediátrica más frecuente y causa una elevada mortalidad si no se trata. Tanto un diagnóstico preciso como un tratamiento rápido son de suma importancia para obtener resultados clínicos óptimos. El tratamiento del RB ha evolucionado a lo largo de los años con un cambio de paradigma: de la enucleación para salvar vidas a estrategias que preservan el globo ocular y la visión. La quimioterapia intraarterial (QIA) se ha convertido en un pilar esencial y eficaz en el manejo del RB. Ha ganado popularidad por tratarse de una técnica de infusión dirigida de agentes quimioterapéuticos mediante un cateterismo superselectivo de la arteria oftálmica (AO). Esto mejora el tratamiento del tumor y reduce la recurrencia y los efectos secundarios sistémicos. Además, a menudo se realiza como procedimiento ambulatorio, lo que reduce la necesidad de estancias hospitalarias prolongadas y mejora la experiencia general del paciente. En esta revisión, analizamos la historia de la QIA, así como su evolución técnica, resultados, complicaciones potenciales y limitaciones.

Retinoblastoma (RB) is the most common pediatric ocular malignancy affecting 1 in 15,000–20,000 live births.1 Almost two-third of all cases are diagnosed before the age of two years and 95% before five years of life.1 It occurs due to a biallelic inactivation of the RB1 retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene. RB may be sporadic, but about 50% are affected by a germline mutation. Approximately 10–15% of unilateral cases may carry a germline mutation.1

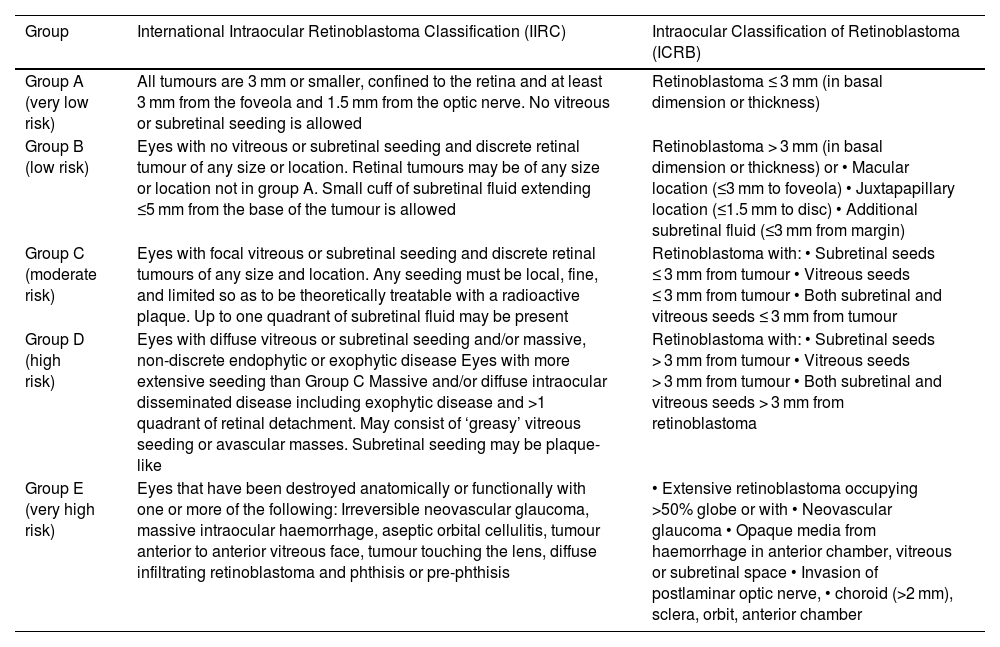

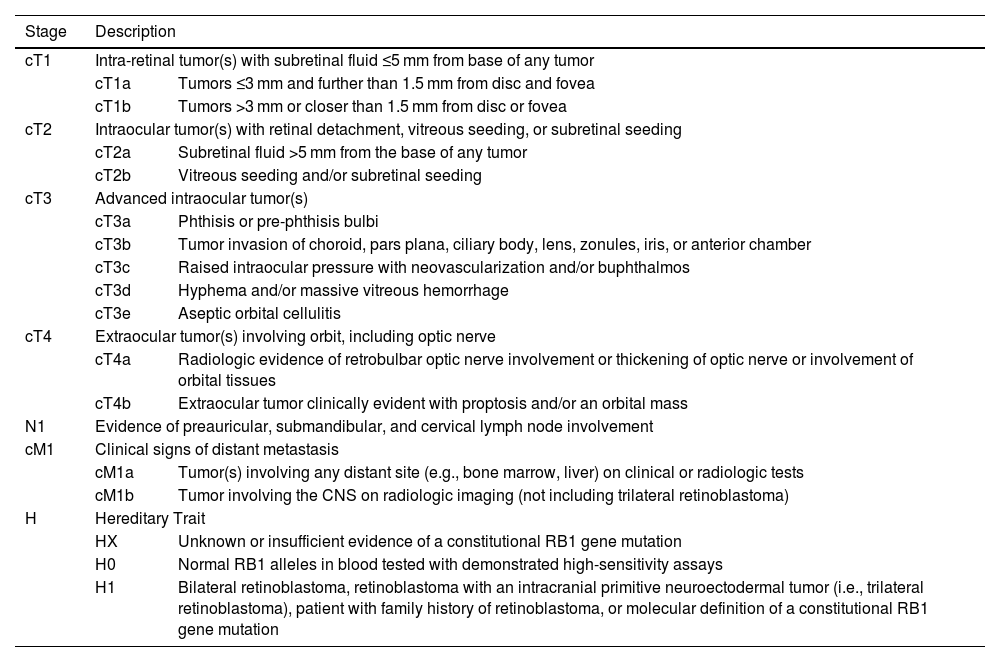

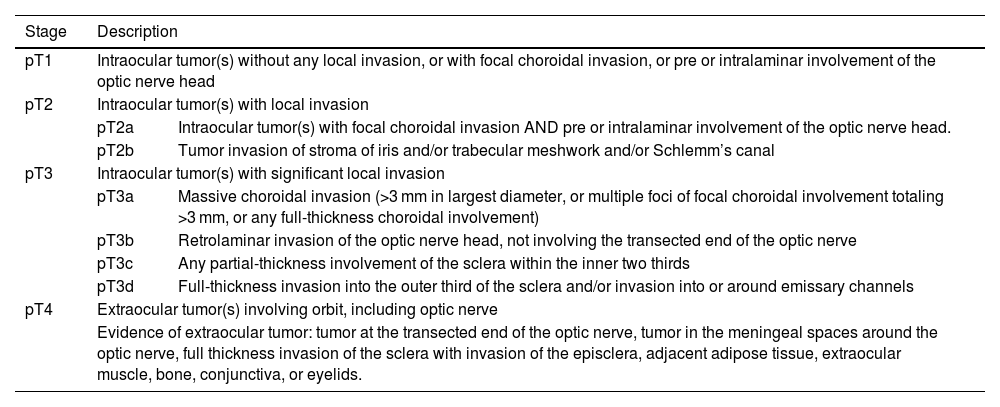

The degree of tumor involvement within the eye is defined by its group. Grouping was historically done with the Reese-Ellsworth System (R-E), introduced in the 1960s.2 Following the inclusion of chemotherapy and focal consolidation in RB treatment, two classification systems were proposed, viz. International Intraocular Retinoblastoma Classification (IIRC) and International Classification for Retinoblastoma (ICRB).2 These systems used similar group names (A–E), but with different definitions (Table 1).2 Subsequently, the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) was proposed defining anatomic involvement and tumor size (T) with nodal (N) and systemic metastasis (M) as well as heritability (H) (Table 2).3 It also includes pathological staging of RB following enucleation (Table 3).3

International Intraocular Retinoblastoma Classification (IIRC) and Intraocular Classification of Retinoblastoma (ICRB) staging of RB.

| Group | International Intraocular Retinoblastoma Classification (IIRC) | Intraocular Classification of Retinoblastoma (ICRB) |

|---|---|---|

| Group A (very low risk) | All tumours are 3 mm or smaller, confined to the retina and at least 3 mm from the foveola and 1.5 mm from the optic nerve. No vitreous or subretinal seeding is allowed | Retinoblastoma ≤ 3 mm (in basal dimension or thickness) |

| Group B (low risk) | Eyes with no vitreous or subretinal seeding and discrete retinal tumour of any size or location. Retinal tumours may be of any size or location not in group A. Small cuff of subretinal fluid extending ≤5 mm from the base of the tumour is allowed | Retinoblastoma > 3 mm (in basal dimension or thickness) or • Macular location (≤3 mm to foveola) • Juxtapapillary location (≤1.5 mm to disc) • Additional subretinal fluid (≤3 mm from margin) |

| Group C (moderate risk) | Eyes with focal vitreous or subretinal seeding and discrete retinal tumours of any size and location. Any seeding must be local, fine, and limited so as to be theoretically treatable with a radioactive plaque. Up to one quadrant of subretinal fluid may be present | Retinoblastoma with: • Subretinal seeds ≤ 3 mm from tumour • Vitreous seeds ≤ 3 mm from tumour • Both subretinal and vitreous seeds ≤ 3 mm from tumour |

| Group D (high risk) | Eyes with diffuse vitreous or subretinal seeding and/or massive, non-discrete endophytic or exophytic disease Eyes with more extensive seeding than Group C Massive and/or diffuse intraocular disseminated disease including exophytic disease and >1 quadrant of retinal detachment. May consist of ‘greasy’ vitreous seeding or avascular masses. Subretinal seeding may be plaque-like | Retinoblastoma with: • Subretinal seeds > 3 mm from tumour • Vitreous seeds > 3 mm from tumour • Both subretinal and vitreous seeds > 3 mm from retinoblastoma |

| Group E (very high risk) | Eyes that have been destroyed anatomically or functionally with one or more of the following: Irreversible neovascular glaucoma, massive intraocular haemorrhage, aseptic orbital cellulitis, tumour anterior to anterior vitreous face, tumour touching the lens, diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma and phthisis or pre-phthisis | • Extensive retinoblastoma occupying >50% globe or with • Neovascular glaucoma • Opaque media from haemorrhage in anterior chamber, vitreous or subretinal space • Invasion of postlaminar optic nerve, • choroid (>2 mm), sclera, orbit, anterior chamber |

AJCC cTNMH retinoblastoma staging.

| Stage | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| cT1 | Intra-retinal tumor(s) with subretinal fluid ≤5 mm from base of any tumor | |

| cT1a | Tumors ≤3 mm and further than 1.5 mm from disc and fovea | |

| cT1b | Tumors >3 mm or closer than 1.5 mm from disc or fovea | |

| cT2 | Intraocular tumor(s) with retinal detachment, vitreous seeding, or subretinal seeding | |

| cT2a | Subretinal fluid >5 mm from the base of any tumor | |

| cT2b | Vitreous seeding and/or subretinal seeding | |

| cT3 | Advanced intraocular tumor(s) | |

| cT3a | Phthisis or pre-phthisis bulbi | |

| cT3b | Tumor invasion of choroid, pars plana, ciliary body, lens, zonules, iris, or anterior chamber | |

| cT3c | Raised intraocular pressure with neovascularization and/or buphthalmos | |

| cT3d | Hyphema and/or massive vitreous hemorrhage | |

| cT3e | Aseptic orbital cellulitis | |

| cT4 | Extraocular tumor(s) involving orbit, including optic nerve | |

| cT4a | Radiologic evidence of retrobulbar optic nerve involvement or thickening of optic nerve or involvement of orbital tissues | |

| cT4b | Extraocular tumor clinically evident with proptosis and/or an orbital mass | |

| N1 | Evidence of preauricular, submandibular, and cervical lymph node involvement | |

| cM1 | Clinical signs of distant metastasis | |

| cM1a | Tumor(s) involving any distant site (e.g., bone marrow, liver) on clinical or radiologic tests | |

| cM1b | Tumor involving the CNS on radiologic imaging (not including trilateral retinoblastoma) | |

| H | Hereditary Trait | |

| HX | Unknown or insufficient evidence of a constitutional RB1 gene mutation | |

| H0 | Normal RB1 alleles in blood tested with demonstrated high-sensitivity assays | |

| H1 | Bilateral retinoblastoma, retinoblastoma with an intracranial primitive neuroectodermal tumor (i.e., trilateral retinoblastoma), patient with family history of retinoblastoma, or molecular definition of a constitutional RB1 gene mutation | |

AJCC pathological staging (pTNM).

| Stage | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| pT1 | Intraocular tumor(s) without any local invasion, or with focal choroidal invasion, or pre or intralaminar involvement of the optic nerve head | |

| pT2 | Intraocular tumor(s) with local invasion | |

| pT2a | Intraocular tumor(s) with focal choroidal invasion AND pre or intralaminar involvement of the optic nerve head. | |

| pT2b | Tumor invasion of stroma of iris and/or trabecular meshwork and/or Schlemm’s canal | |

| pT3 | Intraocular tumor(s) with significant local invasion | |

| pT3a | Massive choroidal invasion (>3 mm in largest diameter, or multiple foci of focal choroidal involvement totaling >3 mm, or any full-thickness choroidal involvement) | |

| pT3b | Retrolaminar invasion of the optic nerve head, not involving the transected end of the optic nerve | |

| pT3c | Any partial-thickness involvement of the sclera within the inner two thirds | |

| pT3d | Full-thickness invasion into the outer third of the sclera and/or invasion into or around emissary channels | |

| pT4 | Extraocular tumor(s) involving orbit, including optic nerve | |

| Evidence of extraocular tumor: tumor at the transected end of the optic nerve, tumor in the meningeal spaces around the optic nerve, full thickness invasion of the sclera with invasion of the episclera, adjacent adipose tissue, extraocular muscle, bone, conjunctiva, or eyelids. | ||

Historically, the goal of RB treatment was preservation of life by performing enucleation.4 With the introduction of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), treatment outcomes and ocular preservation rates improved.5 However, it caused abnormal growth of orbital bones and soft tissues as well as increased risk of a second malignancy in patients with germline disease.4 When intravenous chemotherapy with adjuvant focal laser or cryotherapy were introduced, ocular salvage rates increased up to 100% cases of ICRB group A and B lesions, but not in group D and E lesions.5 Additionally, side effects (ototoxicity, neurotoxicity, and secondary leukemia) were observed.5 RB treatment continued to evolve, with two objectives: reduction of systemic adverse effects and improved ocular salvage.4 This prompted the era of targeted chemotherapy delivery into the ophthalmic artery (OA), termed as Intra-arterial infusion of Chemotherapy (IAC).4

IAC for RB dates back to 1958, when Reese injected Triethylene melamine into the ipsilateral internal carotid artery (ICA) of 31 patients.6 Kiribuchi injected 5-fluorouracil into external carotid artery (ECA) with some promising results.7,8 Kaneko and Inomata studied sensitivity of RB to 12 chemotherapeutic drugs in vitro and found melphalan was most effective.9,10 Kaneko et al. treated 6 patients of relapsed intraocular RBs with intracarotid injection of melphalan (40 mg) and ocular hyperthermia (45 °C for 1 h).9 They reported complete cure in two patients with preserved vision.9 Yamane et al. performed micro-balloon occlusion of the ICA, distal to the OA ostium, followed by OA drug infusion using a guide catheter in 187 patients (610 eyes). Their technical success rate was 97.51%.11 These studies formed the basis of modern-day technical advancements in IAC, with consequent improvement in tumor control and ocular salvage.12

In this review, we aim to provide a detailed evaluation of the evolution of both endovascular and medical treatments, clinical outcomes and therapeutic responses, as well as potential side-effects and complications.

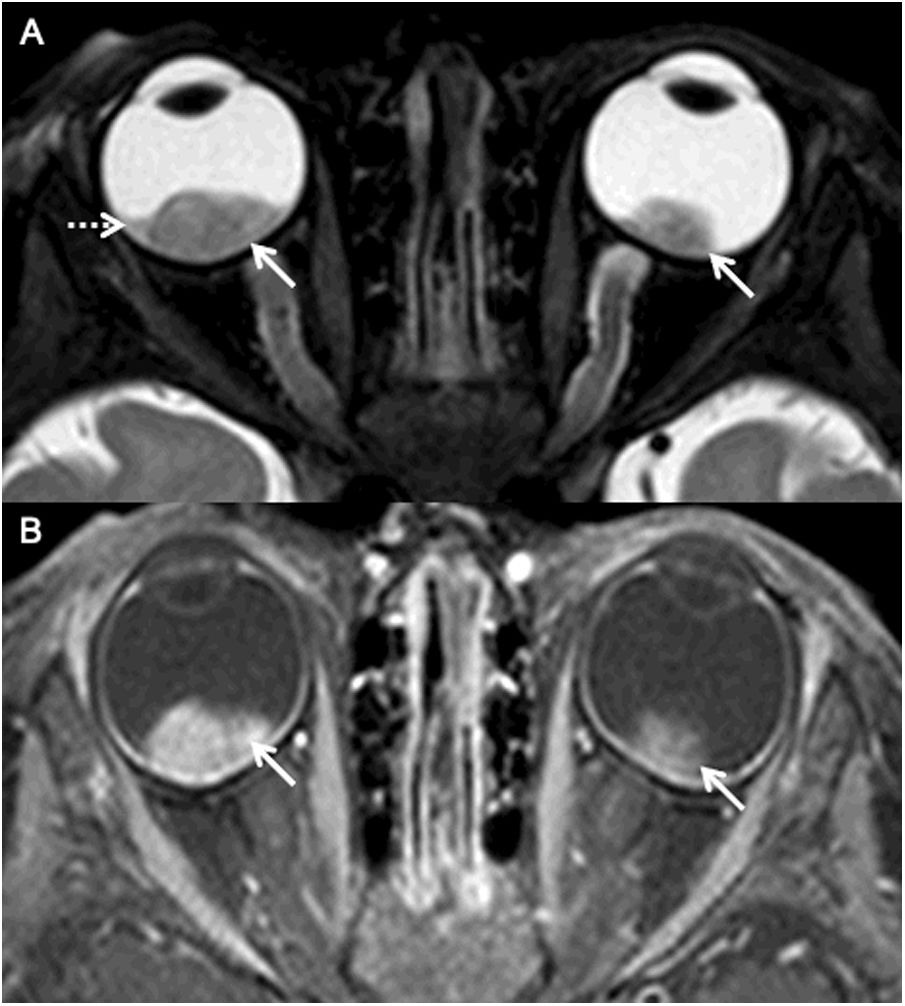

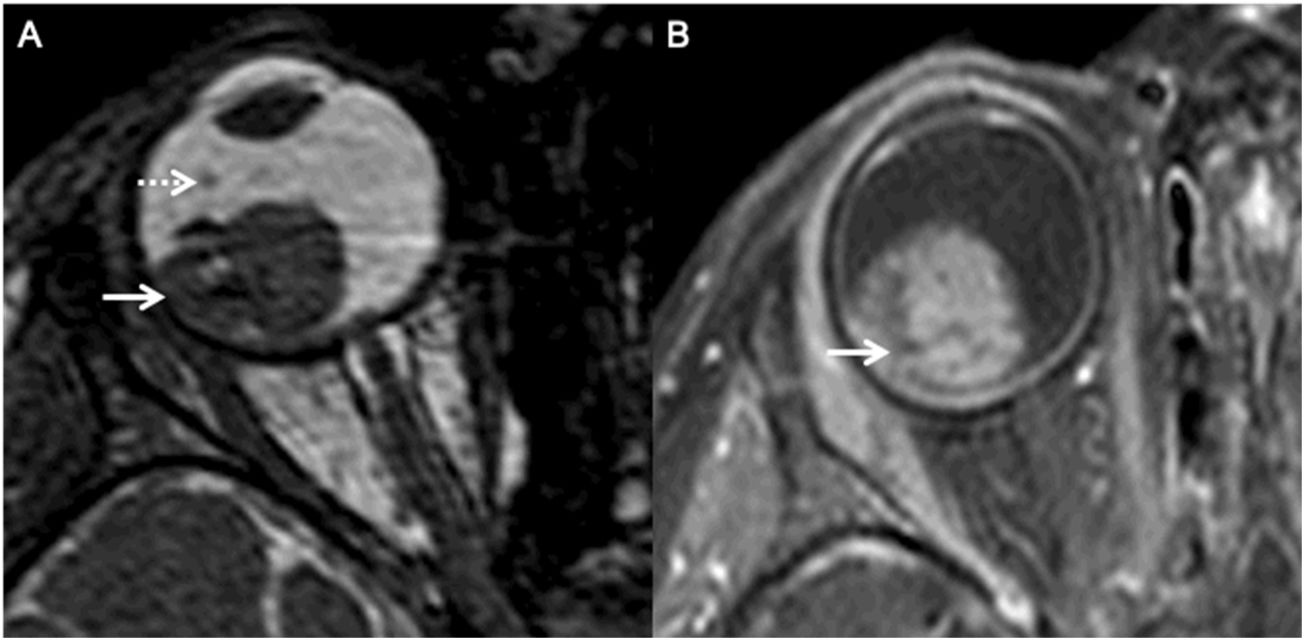

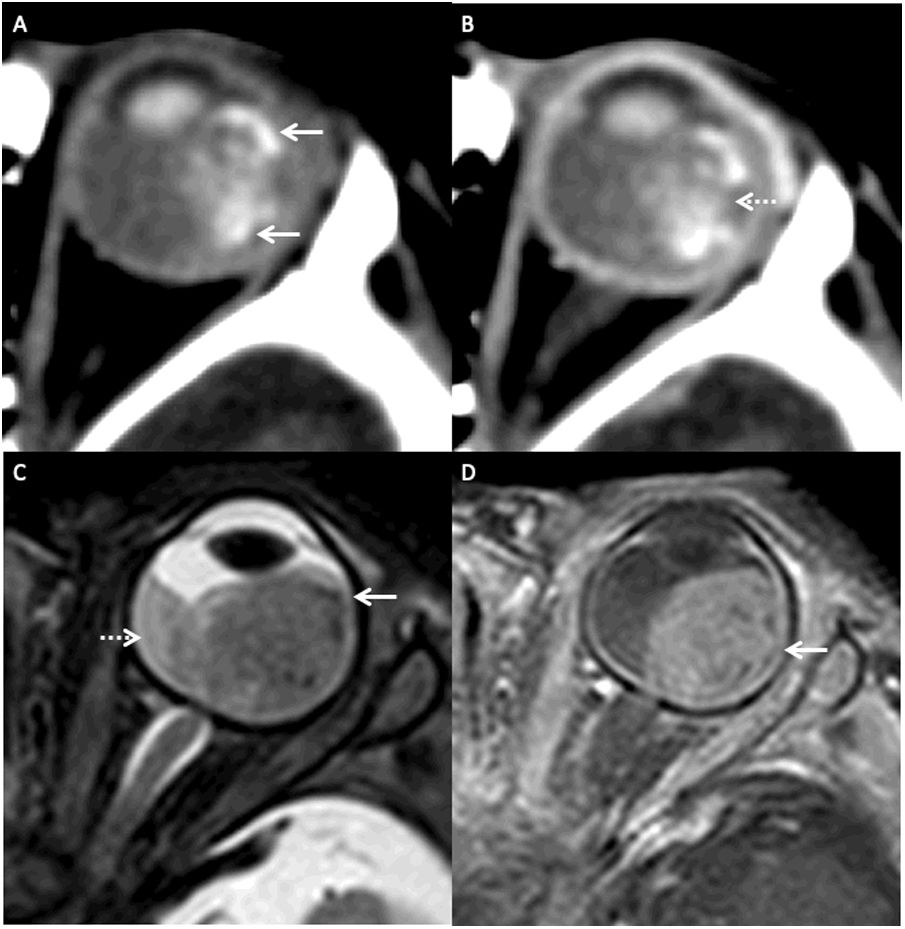

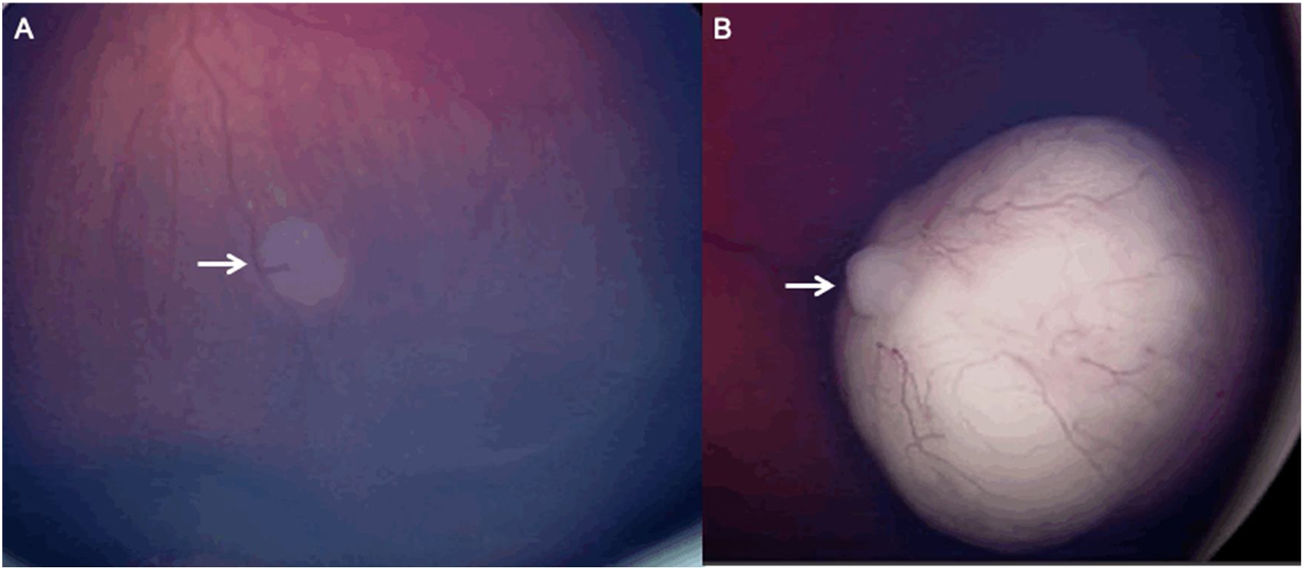

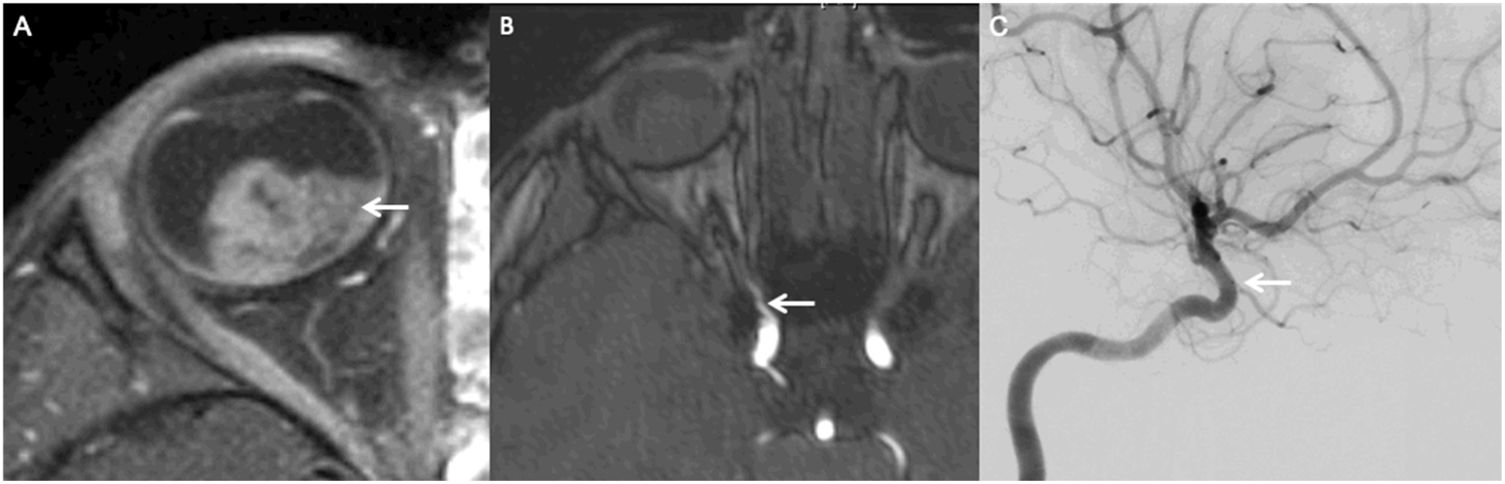

Current practicePatient diagnosis and selectionHigh-resolution contrast-enhanced MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) with MR Angiography plays a crucial role in accurate diagnosis and staging of RB given its excellent spatial resolution and lack of radiation. In the pre-treatment evaluation of RB, MRI facilitates (1) optimal visualization of the tumor and its relation to ocular structures (Figs. 1 and 2); (2) assessment of high-risk features for systemic metastasis (e.g., invasion of the choroid, retrolaminar optic nerve, anterior segment and scleral/extra-scleral invasion)3; (3) intracranial assessment for concomitant midline intracranial midline embryonal tumors (trilateral retinoblastoma) and/or metastasis; (4) evaluation of the anatomy of the ophthalmic artery. Other ophthalmological investigations include ultrasonography, color fundus photography, fluorescein angiography, optical coherence tomography which are key in determining the extent of the disease as well as for guiding treatment decisions (Figs. 3–5).

MRI of a patient with bilateral retinoblastoma (AJCC stage cH1) with a known family history of retinoblastoma. Axial fat saturated T2 image (A) of the orbits shows well defined, hypointense mass lesions (arrows; AJCC cT2a on the right and AJCC cT1b on the left) in both the globes. Note the background subretinal hemorrhage on the right (dotted arrow). Axial fat saturated contrast enhanced T1 image (B) demonstrates avid homogeneous enhancement within both the lesions (arrows).

MRI of a patient with a right sided retinoblastoma (AJCC stage cT2b). Axial constructive interference steady state (CISS) image reveals a well defined lesion along the temporal aspect of the right globe (arrow). Note the punctate, non-contiguous hypointense nodule within the vitreous, representing a vitreous seed (dotted arrow). Axial fat saturated contrast enhanced T1 image (B) demonstrates avid homogeneous enhancement within the retinoblastoma (arrow); however, there is no overt enhancement within the seed.

MRI of a patient with a left sided retinoblastoma (AJCC stage cT2a) presenting with leukocoria. Axial fat saturated T2 image (A) of the left orbit shows a large, well defined, hypointense retinoblastoma (arrow). Note the background subretinal hemorrhage demonstrating a haematocrit level (dotted arrow). Axial fat saturated contrast enhanced T1 image (B) demonstrates avid homogeneous enhancement within the retinoblastoma (arrow).

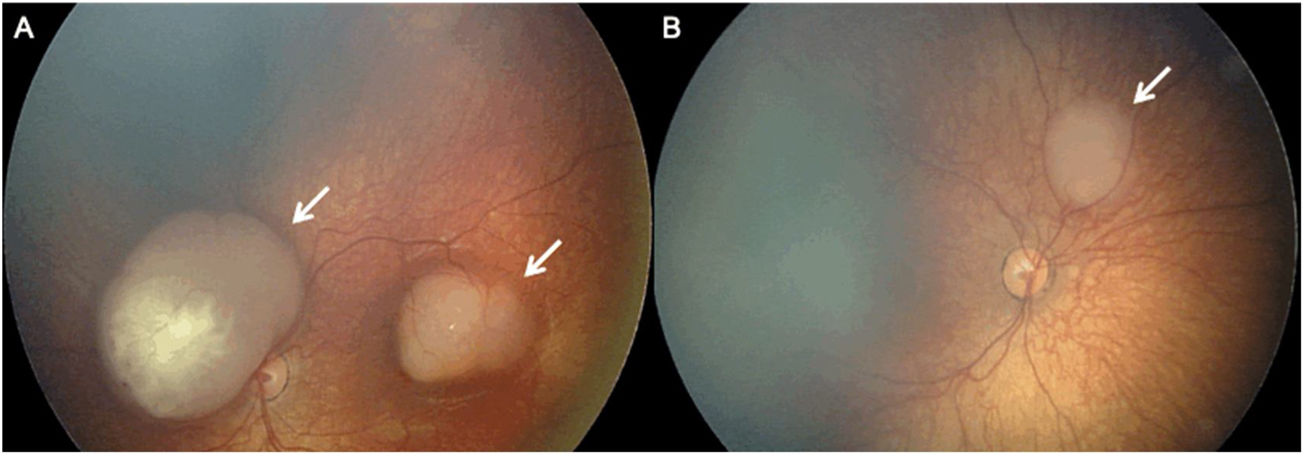

Color Fundus Photography (RetCam) image of a patient with a left sided retinoblastoma (A) reveals a small retinoblastoma along the inferior retinal periphery (arrow). RetCam image of a patient with a right sided retinoblastoma (B) shows a retinoblastoma along the retinal periphery (arrow).

Candidacy for IAC requires a multidisciplinary discussion. In the hands of a skilled operator, IAC can be performed in children <3 mo of age and/or <10 kg, with minor technical modifications.13,14 IAC is used as first-line treatment for unilateral ICRB group B, C, and D (AJCC cT1b, cT2) and bilateral ICRB group D and E (cT2).12 IAC may be used as a second-line treatment for recurrent or persistent tumors with or without subretinal seeding.12

Contraindications include optic nerve invasion and exo-ocular extension as well as presence of trilateral lesions or metastasis, as IAC offers no systemic control.12 Tumors amenable to other treatment modalities (transpupillary thermotherapy, cryotherapy, and intravitreal chemotherapy) and concomitant complications (neovascular glaucoma, vitreous hemorrhage, aseptic cellulitis) are also contraindications.12

TechniqueGobin et al. published their experience in 78 patients (95 eyes) with intraocular RB in 2011. They performed IAC under general anesthesia and used 0.05% nasal oxymetazoline hydrochloride to reduce nasal mucosal blush. A femoral artery access was then obtained and 70 IU/kg of heparin was administered. The OA ostium was catheterized using mostly a straight microcatheter, e.g., Marathon (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) or Magic 1.5 (Balt, Montmorency, France).15 The same group also used the Excelsior SL-10 microcatheter (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts, United States).16 The chemotherapeutic agent (melphalan, topotecan, carboplatin, or methotrexate sodium) was diluted in saline and 20–30 cc was injected in small pulsatile boluses (1 cc/min).15 Jabbour et al. described IAC performed via a trans-femoral approach using a 4-Fr pediatric arterial sheath. They selectively catheterized the ophthalmic artery with the help of a Synchro-10 microguidewire (Stryker Neurovascular, Salt Lake City, Utah, United States) and a Prowler-10 microcatheter (Cordis, Hialeah, Florida, United States). Saline-diluted chemotherapeutic drugs were then pulsed over 30 min to ensure homogeneous drug delivery.17 In a meta-analysis, Ravindran et al. found that the most commonly used technique was a transfemoral approach using a 4 F guide catheter with superselective catheterization of the OA proximal to the ostium with a microcatheter. It is accepted practice that the microcatheter is not entered distal to the OA ostium in order to avoid wedging of blood flow and intimal injury (Fig. 6).18

Intra-arterial chemotherapy for a patient with let eye retinoblastoma. (A) Diagnostic catheter angiography (lateral view) with injection from the ophthalmic artery using a 0.013 “x165 cm Marathon microcatheter navigated over a 0.007” x220 cm Hybrid-007 microguidewire to the ophthalmic ostium. It shows choroidal blush (dotted arrow). (B) General fluoroscopic lateral view of the 4 French x65 cm Berenstein tip diagnostic catheter at the left internal carotid artery (dotted arrow) and the Marathon microcatheter at the ophthalmic ostium (arrow). The intra-arterial infusions were performed under fluoroscopic landmarking.

Narrow calibre, kinking/angulation, or vasospasm of the OA may limit the efficacy IAC (Fig. 7).15,16 In these scenarios, catheterization via the ECA (orbital branch of ipsilateral middle meningeal artery [MMA]) has been advocated.12,15,16 Klufas et al. used this alternate technique and reported tumor control in 17/18 eyes without significant side effects.19 Jia et al. found no statistical difference in clinical outcomes between IAC performed via ECA or ICA-OA routes. No association was found between ocular survival and route of chemotherapy delivery (p = 0.69). ECA catheterization did not predict (hazard ratio [HR] 1.58) or increase chances (HR: 1.64) of enucleation.20

MRI of a patient with a left sided retinoblastoma (AJCC stage cT1b). Axial fat saturated contrast enhanced T1 image (A) demonstrates avid homogeneous enhancement within the retinoblastoma (arrow). Axial source image of a time-of-flight MR Angiography study of the circle of Willis shows a focal kink/stenosis along the proximal course of the right ophthalmic artery, precluding catheterization (arrow). Lateral view of catheter angiography with selective injection of the left internal carotid artery (C) confirms the severe stenosis at the origin of the ophthalmic artery.

Generally, 3 cycles of IAC are administered at q3-4-week intervals.12,21 Currently 3 chemotherapeutic drugs are used:

- 1

Melphalan, a derivative of nitrogen mustard, disrupts DNA replication and transcription.22 Its desired dose is diluted in 30 ml of normal saline and pulsed over 30 min.23,24 Melphalan needs strict dose titration as it can cause local and systemic side effects, including neutropenia (>0.5 mg/kg).12 Filtration through a 2 μm filter before injection is also important as melphalan can crystalize and embolize ocular arteries causing loss of vision.25

- 2

Topotecan inhibits topoisomerase I thus impeding DNA replication.26 Pharmacologically active vitreous concentration is attained until 16 h post-infusion, compared to the rapid decay of melphalan.27 In vivo, melphalan and topotecan have synergistic pharmacokinetics.27,28 Taich et al. first reported its efficacy in vitro without increased hematologic toxicity compared to melphalan monotherapy.29 Currently topotecan is used as part of combined therapy in advanced disease with vitreous or subretinal seeding (ICRB group D or AJCC cT2), or in refractory tumors.30 The recommended dosage is 0.5–2 mg.12

- 3

Carboplatin is a platinum-based agent which interferes with DNA repair.31–33 In a study of 57 carboplatin infusions, with and without topotecan, Francis et al. found that there was no significant effect on electroretinogram responses.34 The overall ocular survival at 2 years was 89.9% (95% CI 82.1–97.9%); only 2 patients developed severe neutropenia.34 However, its use as a first line agent has been discontinued due to ophthalmic toxicity.30 Currently carboplatin is used in combined therapy for ICRB stages D, E tumors, tandem therapy of the contralateral eye, and when the cumulative melphalan dose has surpassed 0.4 mg/kg.30 Recommended dosage is 15–30 mg.12

IAC allows targeted drug delivery at high local concentrations, thereby enhancing its therapeutic effects. This improves tumor control as well as reduces recurrence and systemic side effects.35 Same day discharge is another advantage, reducing hospitalization costs.35

Ocular salvage and enucleation ratesIn a meta-analysis evaluating the success rate of IAC and intravenous chemotherapy (IVC), Chen et al. found the success rate for all ICRB graded lesions was higher with IAC (75.7% [95% CI 65.7%–83.6%] than IVC (69.5% [95% CI 51.9%–82.8%], P < 0.001). For Reese-Ellsworth system graded tumors, the success rate was also higher in IAC (87.1% [95% CI: 78.1%–92.7%] than IVC 77.3% [95% CI: 68.1%–84.4%], P = 0.033).36 Yousef et al. found ocular salvage rate 66% (502/757 eyes).6 Individually, the salvage rate was 74% (124 eyes), 67% (172 eyes), and 61% (461 eyes) after primary, secondary and unspecified IAC, respectively. Ocular salvage rate was 86% in group A–C and 57% group D–E disease.5

Ravindran et al. found an enucleation rate of 32% (174/543 eyes) and overall enucleation effect size of 0.29 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.39).18 Ocular salvage rates were 63.3% in group A–C and 35% in group D–E disease. Overall ocular salvage effect size of advanced disease was 0.66 (95% CI 0.54 to 0.78).18 They found a considerable difference in salvage rates among group E lesions (30–100%).18 The utility of salvage in advanced disease remains questionable, especially in the presence of a high-risk features for metastasis. In such cases, enucleation could be a prudent approach.18

Tumor recurrencePost-treatment imaging for RB includes tumor surveillance to monitor for tumor recurrence or the development of new tumors. MRI is considered the neuroimaging technique of choice for assessing tumor recurrence in RB. The ability to provide comprehensive and detailed images of the eye with excellent soft tissue contrast, multiplanar imaging, assessment of optic nerve and orbital involvement, bilateral eye evaluation, and lack of radiation make the MRI particularly suitable for this purpose.

Following a single cycle, tumor base circumference reduction and tumor thickness reduction by 33% and 46%, respectively, have been reported.37 Rate of retinal recurrence after primary IAC (i.e., first line management) ranges between 0–23%.38 After IAC in 17 cases, Shields et al. reported complete response in 88% cases. Ten of these cases showed no recurrence after a year. Out of 11 eyes with subretinal seeds, 9/11 (82%) showed complete response, 1/11 (9%) showed partial response, and 1/11 (9%) showed recurrence. Among 9 eyes with vitreous seeds, 6/9 (67%), 2/9 (22%), and 1/9 (11%) had complete response, partial response and recurrence, respectively.39 Comparing the outcomes of primary IAC vs secondary IAC (i.e., second line management, after failure of other treatment strategies) (mean follow-up 19 mo), Shields et al. found that primary IAC provided tumor control in 34/36 eyes (94%), subretinal seeds control in 24/24 eyes (100%), vitreous seeds control in 18/21 eyes (86%), and subretinal fluid control in 21/26 eyes (81%). Among the 34 eyes treated with secondary IAC, initial response was seen in all and long-term control in 21/34 eyes (62%).40

Tuncer et al. found main tumor control in 23 out of 24 eyes following two to five IAC cycles. Three cases of tumor recurrence were identified after 6–15 mo of follow up. Complete regression of subretinal seeds was seen in all of 17/24 eyes with recurrence in two eyes. In 12 cases with vitreous seeds, complete and partial initial resolution was seen in 9 and 3 eyes, respectively. Three of the nine showed recurrence on follow up.41 Among 116 eyes with unilateral group D and E unilateral RB, three-year recurrence-free survival was 68.8% (95% CI, 59.2–76.6%) and ocular survival was 88.5% (95% CI, 80.9–93.2%).42

Abramson et al. followed 116 eyes with a genetic RB for 3–48 mo (mean 22.3 mo). They found a tumor focus in 1 eye (out of 41) treated with primary IAC and new tumors in 6 eyes (out of 75) treated with secondary IAC.43 Among 29 eyes treated with primary IAC and 13 eyes treated with secondary IAC, Chen et al. found a 2-year recurrence-free survival rate of 71.9% (95% CI, 49.4–85.7) and 75% (95% CI, 40.8–91.2), respectively.44

Different strategies have also been implemented to achieve a favorable outcome. Shield et al. performed rescue IAC in 12 patients, i.e., after failure of primary and secondary IAC. Their protocol included melphalan (5–7.5 mg) with or without topotecan (1 mg). After a median of 3 cycles (range 2–4 cycles) and a mean follow-up of 20 mo (range 7–36 mo), tumor control was found in 9 eyes (75%) and ocular salvage in 8 eyes (67%).45 In another study on rescue IAC with a median follow up of 7 mo (range 3–31 mo), tumor control was seen in 10/12 eyes (83%) and globe salvage in 9/12 eyes (75%).46 Francis et al. found a one-year ocular survival, progression-free ocular survival and recurrence-free ocular survival of 96% (95% CI 93–99%), 88% (95% CI 88–94%) and 74% (95% CI 67–81%), respectively, using IAC. However, with the combination of intravitreal chemotherapy, an improvement in these parameters was observed, i.e., 96% (95% CI 94–99%), 93% (95% CI 89–96%) and 78% (95% CI 72–83%), respectively.34

Visual outcomeSuzuki et al. reported that in cases with foveolar involvement treated with IAC, only 58% (54/95 eyes) had a visual acuity score greater than 0.01. In those without initial foveolar involvement, 51% (55/107 eyes) and 36% had a visual acuity of >0.5 and >1.0 (almost normal), respectively.47 Munier et al. reported good visual acuity (0.05–0.63) in 6 patients and poor acuity (0.01–0.2) in 4 patients (out of 13) following IAC.48 Reddy et al. reported no deterioration of vision in 8 patients after IAC. Best-corrected visual acuity was ≥20/40 in 71% (5/7 eyes) before IAC as compared to 77% (7/9 eyes) after IAC. Seven patients recorded normal retinal electroretinograms post IAC.49

Metastasis and deathAbsence of metastasis 5 years post-therapy is an indicator of cure.51 Selection of appropriate treatment modality is crucial in ensuring a favorable outcome; 17% of group D and 24% of group E eyes harbor high-risk pathology, and IAC, without systemic chemotherapy, would offer no protection from metastasis.50

Yousef et al. found 20 out of 613 patients eventually developed of metastasis.6 They also found 14 reports of death among 655 patients (2.1%; 11 caused by RB and 3 by second malignant neoplasms).5 Ravindran et al. found 6 out of 20 studies reporting a combined 8 cases of metastatic disease out of 513 patients (1.6%).18 Abramson et al. reviewed data over 10 years across centres in New York City, Philadelphia, Sao Paulo, Siena, Lausanne, and Buenos Aires. They found 3 metastatic deaths out of 1139 patients.51 However, they did not discuss the rate of metastases and only focussed on the single outcome of metastatic deaths. Furthermore, they did not provide any time-to-event analysis or a median follow-up time among other data.52

Studies have also evaluated survival following primary and/or secondary IAC with different follow up periods. At a mean follow up of 32 mo (range, 3–95 mo), a survival rate of 96% (25/26) was reported by Rojanaporn et al.53 Ong et al. report 3 out of 17 cases of CNS metastasis (2 group E and 1 group B). These patients underwent enucleation, but 2 patients died.54 Manjandavida et al. reported no metastasis or death in 12 years.12

ComplicationsTechnical difficultiesInstability of the catheter at the OA ostium and vasospasm are common.12 Yousef et al. report 1.7% (40/2390) of catheterizations were unsuccessful.5 Stenzel et al. reported non-application of IAC due to limitations with OA catheterization (8.2%), variants of the meningeal collaterals (12.2%) or alternate retinal supply (9.2%).55 In such cases catheterization of the orbital branch of the ipsilateral MMA or the technique described by Yamane et al. may be used.11 Other proposed techniques to improve stability include microcatheter shaping, retrograde approach via the posterior communicating artery.56 IAC via the superficial temporal artery has also been reported.57

Vascular steal in the OA, evidenced by poor choroidal blush, results in poor drug delivery.56 This may occur due to vasospasm or triggering of collaterals.58 In such cases balloon occlusion of the ICA may not be effective, and IAC via the orbital branch of the MMA may be considered.58 Bertelli et al. suggested occlusion of extra-orbital ECA branches with a cyanoacrylate-based synthetic and Lipiodol to redirect intra-orbital blood flow and found no statistical difference in clinical outcomes.58 Quinn et al. also demonstrated improvement of choroidal blush from the OA after balloon occlusion of the internal maxillary artery (IMA) or MMA.57 They advanced a 4 × 11 mm Scepter XC balloon microcatheter (MicroVention, Aliso Viejo, California, United States) over a 0.014-inch microwire via a femoral sheath into the IMA or MMA.57

The small femoral artery calibre relative to the sheath is another challenge. The outer diameter of a 4 F catheter is 1.33 mm which may be larger than the femoral artery diameter in patients <10 kg. This may cause vasospasm, thrombosis, or arterial disruption.34 About 8%–14% of children who underwent cardiac catheterization using a trans-femoral approach had femoral artery injury causing leg length discrepancy with 33% cases of arterial thrombosis.34 Authors have performed femoral artery compression and pulse oximeter monitoring of the great toe to reduce incidence of retroperitoneal hematoma, while avoiding excessive compression which may lead to vasospasm or ischemia.34 Sweid et al. mentioned catheterization of the femoral artery using a Marathon and a Synchro10 all the way to the OA, without a guide catheter, as an effective way to avoid femoral artery dissection.59 However, this is not a common technique.

Experience from adult cardiovascular studies has led to trans-radial access being implemented for pediatric neurointerventions.60 Reported advantages of trans-radial approach include easier hemostasis, reduced incidence of arteriovenous fistulisation, and faster patient mobilization.61 It eliminates limb ischemia due to the dual arterial supply to the hand via the radial and ulnar arteries.61,62 In a case series of five RB patients treated transradial IAC, Al Saiegh et al. reported 100% technical success, with two patients getting repeat IAC via the same wrist. They did not report thromboembolic or local complications.62 However, radial access is not always a feasible option given the small radial artery diameter in children. In a study on 134 children (mean age 8.9 ± 5.8 years; mean weight 37.2 ± 27.5 kg) by Alehaideb et al., the mean-corrected radial artery diameter was 1.86 ± 0.44 mm with no gender- or laterality-based differences. However, a correlation of diameter with age (R = 0.75; P < 0.00001) and weight (R = 0.74; P < 0.00001) was noted with a linear increase in arterial growth in the early childhood after which plateauing to adult sizes in adolescents was observed.63

Radiation dose during IAC is another important aspect due to the age demographic and increased risk of second primary malignancy.64 Gobin et al. found that the fluoroscopic times were shorter for OA catheterization (5 min 36 s) than MMA catheterization (8 min 33 s) or the balloon technique (9 min and 39 s). The radiation doses measured at the tragus demonstrated 5.55 mGy for the treated eye and 1.68 mGy for the contralateral eye. At the eyelid, 0.99 mGy for the treated eye and 0.52 mGy for the contralateral eye were detected.65 Vijaykrishnan et al. found that mean irradiation doses were 0.19173 Gy and 0.03533 Gy at the skin on the affected and contralateral eyes, respectively. Estimated dose to the lens was 0.16 Gy, which could be cataractogenic. Estimated dose from a single session to other radiosensitive organs was lesser than the minimal toxic levels.66 Opitz et al. found the diagnostic reference levels for IAC to be lower compared to other complex endovascular interventions.67

Radiation dose reduction can be achieved using collimation, reduced source-image distance, use of single plane and roadmaps rather than subtraction angiograms.64 However, low radiation doses are accompanied with poor image quality, limiting adequate catheterisation. Cooke et al. demonstrated that changing fluoroscopic settings to 4 pulses/s (from 7.5 pulses/s) and reducing dose level to the detector to 23 nGy/pulse (from 36 nGy/pulse) results in dose reduction per pulse by 35% (20.1 ± 11.9 mGy at mean fluoroscopic time of 8.5 ± 4.6 min). Dose to the lens and skin were also reduced to 0.18 ± 0.10 mGy and 0.7–7.0 mGy, respectively.64

Ocular complicationsLoss of vision is a dreaded complication and may be due to ischemic and occlusive chorioretinopathy, central retinal artery occlusion, vitreous hemorrhage, or retinal detachment (RD).12 Yousef et al. found ocular toxicities (vascular ischemia, chorioretinal atrophy) in 45 out of 725 eyes (6.2%) post-IAC6 Ravindran et al. reported retinal or choroidal ischemia in 38 of 289 eyes (13.1%). The pathogenesis of the vascular events is thought to be due to the technique and cumulative drug toxicity.12 Both melphalan and carboplatin trigger retinal endothelial cell migration, apoptosis, and increase expression of intra-cellular adhesion molecule-1 [ICAM-1] and interleukin-8). Melphalan increases monocyte adhesion to human retinal endothelial cells.68 In a retrospective evaluation of vascular events of primary unilateral IAC performed in the early era (2009–2011) vs. the recent era (2012–2017), Dalvin et al. followed patients using examination under anesthesia (EUA) monthly along with anterior segment evaluation, indirect ophthalmoscopy, B-scan ultrasonography, fundus photography and RetCam (Clarity, Pleasanton, California, United States). They found that ophthalmic vascular event rates had reduced with time, with significantly lesser events in the recent era (59% vs. 9% per eye and 23% vs. 3% per infusion, P < 0.01). In fact, no IAC-induced vascular events were found in 72 consecutive infusions (21 eyes) between 2016 and 2017. They attributed this to increased experience and improved techniques such as elimination of guidewires, catheter advancement only to the OA ostium, and changes in the pulsatile nature of infusion.69

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RD) has been reported in 8–16% of cases post primary IAC, likely from rapid regression of endophytic lesions.28 Yousef et al. found RD and vitreous hemorrhage (VH) in 11 of 57 eyes (19.3%) and 30 of 166 eyes (18.1%), respectively.5 Ravindran et al. found reports of RD in 21 of 90 eyes (23.3%) and VH in 50 of 421 (11.9%).18 Muen et al. discussed that melphalan can worsen radiation angiopathy which would contribute to vitreous or retinal hemorrhage.70 Yousef et al. found reports of optic atrophy in 3 of 87 eyes (3.4%) and phthisis in 5 of 189 eyes (2.7%).5 They also found reports of dysmotility in 10 of 154 eyes (6.5%) and ptosis in 24 of 177 eyes (13.6%).5 Muen et al. reported 6 (of 17) cases of oculomotor palsy resulting in ptosis and pupillary involvement. All, but one resolved after 2–6 mo.70 Yousef et al. and Ravindran et al. also reported transient periorbital edema in 66 of 196 eyes (33.7%) and 25 of 182 (13.7%), respectively.5,18 Self-resolving complications include focal madarosis, forehead erythema, and loss of eyelashes.5,12

Systemic complicationsGeneralThough IAC reduces systemic toxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs, cases of neutropenia have been published. Yousef et al. found, 34 of 577 children suffered neutropenia and 2 of 546 children (0.4%) needed blood transfusion.6 Ravindran et al. found neutropenia in 38 of 230 patients (16.5%).19 Fever, bronchospasm and nausea/vomiting have also been reported.5,18

Cardiovascular complicationsYamane et al. reported transient bradycardia following melphalan administration, likely from a vasovagal reflex.11 Klumpp et al. reported hemodynamic instability in 8 patients triggered by OA catheterization. They observed a drop of end tidal CO2 to 21 mmHg (normal 33–40 mmHg) with reduced oxygen saturation and hypotension. Patients were treated with vasopressors and fluids; all responded well to supportive treatment and were discharged after the procedure.50 The authors suggested an acute pulmonary hypertensive state due to vasoactive hormone release and vagal stimulation, from OA catheterisation, to be the underlying cause.50

Phillips et al. reported cardio-respiratory reactions developed during 35 procedures (24%; 95% CI, 18–32%). All reactions occurred during second or subsequent catheterization (39%; 95% CI, 29–49%) and were characterized by hypoxia, reduced lung compliance, systemic hypotension and bradycardia. All adverse events were successfully treated.71

Neurovascular complicationsRojanaporn et al. reported a case of a transient ischemic attack.53 A few cases of stroke after IAC have been published, including a case of a parietal stroke ipsilateral to the side of the IAC as reported by Leal-Leal et al.72 Ammanuel et al. also reported a case of a small infarct two days after IAC.73 Another case of a left MCA infarct was reported by De la Huerta et al. post IAC.74

LimitationsDespite merits, IAC is less effective against advanced group E lesions and vitreous seeding. It provides no protection against extra-ocular invasion and metastasis. Given that enucleation would be avoided due to IAC, the opportunity to have histopathological evaluation for high-risk features for metastasis may be missed. IAC does not protect against pineoblastoma and secondary tumors.36 IAC also needs skilled interventional neuroradiologists with a robust clinical team and close follow-up with EUA to ensure appropriate outcome.

ConclusionIAC has revolutionized RB treatment. Unification of the classification system used for retinoblastoma will ensure uniformity and effective communication among healthcare professionals worldwide. With increased experience and newer techniques, complete cure, ocular salvage and vision preservation are now possible along with reduced systemic complications of intravenous systemic chemotherapy. It must also be acknowledged that IAC is not devoid of complications and requires a reasonable amount of skill. Appropriate patient selection is key as IAC offers limited value in advanced lesions and no protection against metastasis.

FundingThe authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not- for- profit sectors.