Research shows a high prevalence of psychopathology among medical students. This study aims to assess the time trend of depression, anxiety, self-concept and obsessive-compulsiveness in medical students within the first year (short-run) and over the years (long-run) of medical school, and to measure if self-concept and obsessive-compulsiveness predict anxiety and depression trends.

MethodsAt baseline, 183 freshman students that enrolled at FMUP in the 2002/03 academic year were recruited; from these, 71 (39%) participated in the short-run study and were assessed at the beginning and at the end of the first year and 151 (83%) participated in the long-run study (assessed in the first, third and fifth year). Participants answered three self-report questionnaires: the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS), the Maudsley Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (MOCI) and a self-concept scale.

ResultsIn the long-run, there was a negative linear trend with time for the MOCI score (B=–0.68, p<0.001) and for the HADS anxiety score (B=–0.28, p<0.001), a positive linear trend for self-concept (B=1.37, p<0.001) and no association with depression (B=–0.05). The short-run results were opposite given that anxiety, depression and obsessive-compulsiveness increased and no differences were found for self-concept.

After adjusting for self-concept and obsessive-compulsiveness, there was no effect of time on anxiety but there was a negative interaction between self-concept and time on depression scores.

ConclusionsThe effect of time on depression is moderated by a protective effect of self-concept, while obsessive-compulsiveness explained time trends on anxiety scores.

It is important to understand and find the pathways of anxiety and depression to improve medical students’ mental health.

Medical students’ mental health has been exhaustively studied showing high scores of stress, anxiety, depression and burnout when compared with other groups of the same age group or even in other graduate degrees.1–3

Research has shown an association between personal characteristics and anxiety and/or depression scores1–5; and some studies have focused on personal characteristics such as self-concept, obsessive-compulsiveness and distress.4,6

According to some authors, self-concept is a multidimensional construct, having one global dimension (global self-concept), to which all of the other dimensions contribute and this is related with self-esteem.3,7 In literature, this has been linked with depression symptoms8 and a Portuguese study demonstrated a negative correlation between global self-concept, and anxiety and depression symptoms.9

An obsessive-compulsive disorder consists of obsessive thoughts such as excessive doubting and compulsive behaviours such as frequent washing.10 It seems that obsessive-compulsive symptoms are associate with perfectionism and consequently with depression.2

The relation between certain personality traits measured early in the course of medical school and later mental health among junior physicians during postgraduate internship training has been highlighted.11 A twelve year longitudinal study showed that stress, burnout and satisfaction with medicine as a career in doctors correlate and were partially predicted by measures of personality traits taken five years earlier.5

The aim of this prospective study was: 1 - to assess the time trend of depression, anxiety, self-concept and obsessive-compulsiveness in the first year of medical school (short-run study); 2 - to assess the time trend of depression, anxiety, self-concept and obsessive-compulsiveness over the years of medical school (long-run study) and 3 - to measure if the self-concept and obsessive-compulsiveness moderates the anxiety and depression time trends.

Material and methodsParticipantsAt baseline, 183 freshman students that enrolled at FMUP in the 2002/03 academic year were recruited; from these, 71 (39%) participated in the short-run study and 151 (83%) participated in the long-run study.

In the short-run study, participants were assessed twice in their first year: at the beginning of the academic year (October 2002) and at the end of the academic year (June 2003).

For the long-run study, participants were assessed at three different moments: the beginning of the first academic year (October 2002), the beginning of the third year (November 2004) and the beginning of the fifth year (November 2006). Of 151 participants enrolled in the long-run study, 145 (96%) participated in the third year and 77 (51%) participated in the fifth year.

InstrumentsIn both studies, participants had to answer three self-report questionnaires. The Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS)12,13 was used to assess anxiety and depression symptoms. This scale consists of 14 items (seven items for each dimension) with four ordinal options (0-3 points). The higher (lower) the score, the higher (lower) the anxiety or depression. A score higher than seven, on either sub-scale, indicates borderline anxiety or depression.

The obsessive-compulsive symptoms were measured with the Maudsley Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (MOCI).14 This questionnaire is widely employed in clinical settings and consists of 30 true-false items. The higher (lower) the score, the higher (lower) the obsessive and compulsive symptoms.

A 20 item self-concept scale15 was used, where the higher (lower) the score, the higher (lower) the self-concept.

Statistical analysisThe average score intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) was used to measure the variance attributed to differences among subjects of the total variance and indirectly measuring the variance attributed to differences within subjects.

Paired sample t-tests and linear mixed-effects models were used to estimate short- and the long-run trends in each dimension assessed and to measure the influence of self-concept and compulsive behaviour on the anxiety and depression scores.

All statistical analyses were calculated in R 2.8.0.

ResultsThe ICC for anxiety, depression, self-concept and obsessive-compulsive symptom scores indicated moderate agreement between all of the different observations (short and long measurements). The ICC was 0.66, 0.53, 0.60 and 0.65 for the anxiety, depression, self-concept and obsessive-compulsive scores, respectively.

Short-run effectThe comparison between students who participated in the short-run study (n=71) and students who did not participate (n=112), had no statistical differences in the first assessment between anxiety, depression, self-concept and obsessive-compulsive scores.

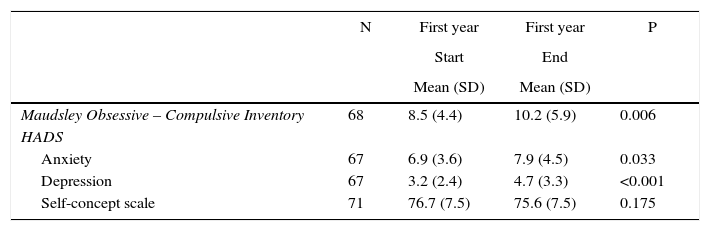

However, there was a statistical significant increase in the score of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and in the anxiety and depression score within the first year. The anxiety mean score increased from 6.9 (SD=3.6) to 7.9 (SD=4.5) and the depression mean score increased from 3.2 (SD=2.4) to 4.7 (SD=3.3) (Table 1). The obsessive-compulsive score increased from 8.5 (SD=4.4) to 10.2 (SD=5.9). In the self-concept scale score, there were no statistical significant differences (76.7 (SD=7.5) versus 75.6 (SD=7.5)) (Table 1).

The short-run effect (within the first year) for obsessive-compulsiveness, anxiety, depression and self-concept.

| N | First year | First year | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Maudsley Obsessive – Compulsive Inventory | 68 | 8.5 (4.4) | 10.2 (5.9) | 0.006 |

| HADS | ||||

| Anxiety | 67 | 6.9 (3.6) | 7.9 (4.5) | 0.033 |

| Depression | 67 | 3.2 (2.4) | 4.7 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Self-concept scale | 71 | 76.7 (7.5) | 75.6 (7.5) | 0.175 |

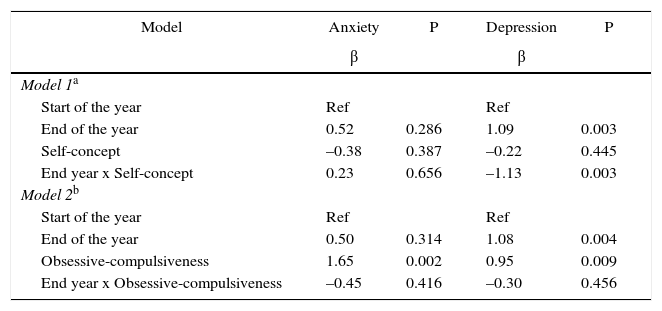

After adjusting for obsessive-compulsiveness, there was a positive association of the obsessive-compulsive scores with anxiety and depression scores. After adjusting for self-concept, the effect of time in anxiety scores disappeared and there was a negative interaction between self-concept and time on depression scores, showing that the association of self-concept with depression was modified by time of the assessment. The association between self-concept and depression was stronger at the end of the academic year (Table 2).

Models to predict the anxiety and depression scores within the first year.

| Model | Anxiety | P | Depression | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | |||

| Model 1a | ||||

| Start of the year | Ref | Ref | ||

| End of the year | 0.52 | 0.286 | 1.09 | 0.003 |

| Self-concept | –0.38 | 0.387 | –0.22 | 0.445 |

| End year x Self-concept | 0.23 | 0.656 | –1.13 | 0.003 |

| Model 2b | ||||

| Start of the year | Ref | Ref | ||

| End of the year | 0.50 | 0.314 | 1.08 | 0.004 |

| Obsessive-compulsiveness | 1.65 | 0.002 | 0.95 | 0.009 |

| End year x Obsessive-compulsiveness | –0.45 | 0.416 | –0.30 | 0.456 |

The comparison between students who participated in the fifth year (n=77) and students that did not participate (n=74), showed no statistical differences between their anxiety, depression, self-concept and obsessive-compulsive scores in the first assessment.

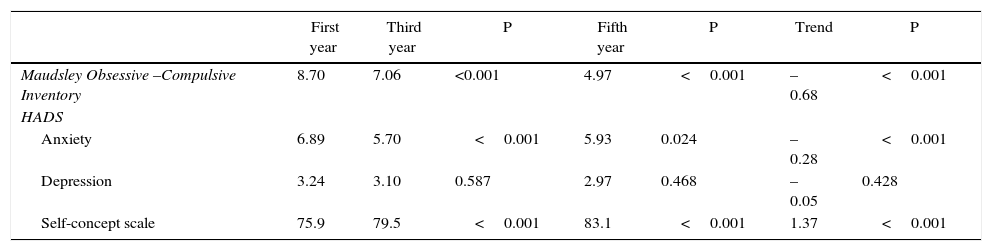

The obsessive-compulsive score showed a negative trend with time and inversely, self-concept showed a positive trend. In the case of the HADS assessment, there was a negative trend with time and anxiety and no statistical significant trend with depression scores. The obsessive-compulsive mean score diminished 0.68 points and the anxiety mean score diminished 0.28 points each year; the self-concept mean score increased 1.37 points each year (Table 3).

The long-run effect (between the first, third and fifth year) for obsessive-compulsiveness, anxiety, depression and self-concept.

| First year | Third year | P | Fifth year | P | Trend | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maudsley Obsessive –Compulsive Inventory | 8.70 | 7.06 | <0.001 | 4.97 | <0.001 | –0.68 | <0.001 |

| HADS | |||||||

| Anxiety | 6.89 | 5.70 | <0.001 | 5.93 | 0.024 | –0.28 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 3.24 | 3.10 | 0.587 | 2.97 | 0.468 | –0.05 | 0.428 |

| Self-concept scale | 75.9 | 79.5 | <0.001 | 83.1 | <0.001 | 1.37 | <0.001 |

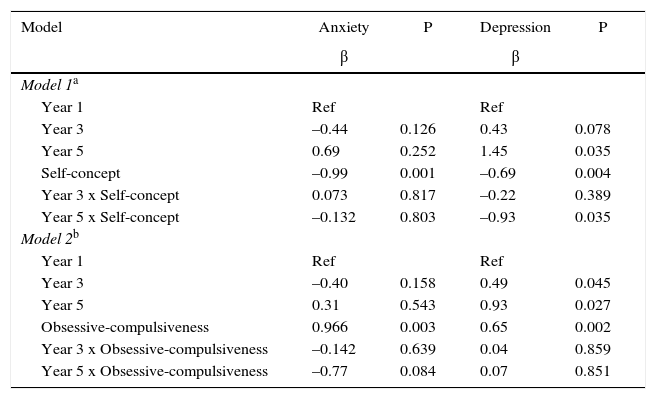

After adjusting for self-concept and obsessive-compulsiveness, there was a negative association of self-concept with anxiety (β=–0.99, p=0.001) and depression scores (β=–0.69, p=0.004) and a positive association of obsessive-compulsive symptoms with anxiety (β=0.966, p=0.003) and depression scores (β=0.65, p=0.002). The effect of time on anxiety scores disappeared and there was a positive association between time and depression. However, the interaction term, showed that the association of self-concept with depression was modified by time, as time passes, the association between self-concept and depression is stronger (Table 4), given that the protective effect of self-concept in the fifth year is higher (β=–0.93, p=0.035) than compared with that of the first year.

Models to predict the anxiety and depression scores at long-run.

| Model | Anxiety | P | Depression | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | |||

| Model 1a | ||||

| Year 1 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Year 3 | –0.44 | 0.126 | 0.43 | 0.078 |

| Year 5 | 0.69 | 0.252 | 1.45 | 0.035 |

| Self-concept | –0.99 | 0.001 | –0.69 | 0.004 |

| Year 3 x Self-concept | 0.073 | 0.817 | –0.22 | 0.389 |

| Year 5 x Self-concept | –0.132 | 0.803 | –0.93 | 0.035 |

| Model 2b | ||||

| Year 1 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Year 3 | –0.40 | 0.158 | 0.49 | 0.045 |

| Year 5 | 0.31 | 0.543 | 0.93 | 0.027 |

| Obsessive-compulsiveness | 0.966 | 0.003 | 0.65 | 0.002 |

| Year 3 x Obsessive-compulsiveness | –0.142 | 0.639 | 0.04 | 0.859 |

| Year 5 x Obsessive-compulsiveness | –0.77 | 0.084 | 0.07 | 0.851 |

The results showed an important tracking effect of the scores of anxiety and depression, self-concept and obsessive-compulsiveness over medical school, meaning that overall, the personal variables that were studied are somehow intrinsic or more stable (the variance attributed to differences among subjects of the total variance ranged from 0.53 and 0.66). Nevertheless, there are opportunities for some intervention initiatives in order to improve medical student's mental health given that the variance attributed to differences within subjects ranged from 0.34 and 0.47, showing that there was some variability in the mean scores of anxiety, depression, self-concept and obsessive-compulsiveness within subjects over the years. This can be showed by the mean scores of anxiety that ranged from 5.7 to 7.9 over the course of medical school, depression scores ranged from 2.7 to 4.9 and obsessive-compulsive scores ranged from 4.97 to 10.2.

The maximum scores of anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsiveness and the minimum of self-concept were reached at the end of the first academic year. It is important to have in consideration that this study happened before some curricular reforms and because of this, the first examination period as university students happened at the end of the academic year. Considering the four moments of our study, this was the time at which higher scores of distress were observed. These results corroborate the findings of Bolger,16 who shows that as the examination period approaches, individuals show increased anxiety scores.

The crude analysis performed over the course of medical school showed that there was a negative trend with time for the anxiety and obsessive-compulsive scores followed by a positive trend with self-concept scores. These findings show that all of the studied variables’ time trends are closely related to each other. There was no trend with time for the depression scores.

When we measured to what extent the obsessive-compulsive scores and self-concept explained the anxiety and depression trends, results showed that the anxiety trend was attenuated and the depression scores showed a negative interaction with time trend and self-concept.

The attenuation of the anxiety trend by self-concept and obsessive-compulsiveness could be explained by adaptation to the new academic environment throughout the medical school, due to a learning curve of adaptive coping strategies, which increases the sense of control by the students and consequently their self-concept (self-esteem) increased, while obsessive-compulsive and anxiety scores decreased.

These findings could suggest that anxiety scores are more related with academic adaptation given that in the first year students did not yet have time to adapt to the new environment and learn adaptive coping strategies, which is showed by an increase in obsessive-compulsive scores and the maintenance of similar scores of self-concept.

This study also indicated that the effect of self-concept in depression is moderated by the years, showed by significant interaction of self-concept and the years of medical school. As the years progress, the relation between self-concept and depression increases, which means the same level of self-concept in the fifth year will have a more protective effect of depression compared with that of the first year. The same happened in the short-run study, where the students who maintained the same level of self-concept immediately before the examination period had a higher protective effect of self-concept. In moments of higher depression (end of the first and the fifth year), the self-concept had a strong protective relationship with depression.

In conclusion, the main result that our study provides is that the trend of anxiety at the long-run was explained by self-concept and/or obsessive-compulsiveness and that the trend at the short-run had similar results, showing the importance to design specific targeted interventions.

Another finding that might arise relates to the increase of depression with time, independently of the relation between self-concept with depression and obsessive-compulsiveness with depression.

Finally, this study shows that self-concept is an important factor to diminish depression when this is presented with high scores.

It is also important to point out that these students were all recent high school graduates, who were admitted to FMUP considering only their academic achievements, which can lead us to rethink medical school admission. Nevertheless, additional research to improve our understanding of the causes leading to medical student distress and to investigate potential solutions to overcome these situations is likely to benefit not only our students, but have a strong repercussion on future physician workforce.

This study highlights the need to understand and to improve medical students’ mental health.

The authors are indebted to the suggestions made at the start of this study by Professor Rui Mota Cardoso, from the Department of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health, Porto.