Secondary arm lymphedema is a feared late iatrogenic side effect of breast cancer survivors with a negative impact on patient's self-image and quality of life. Its reported incidence is extremely variable, from 6% to 80%, as well as the effectiveness of the multimodal decongestive lymphedema therapy.

In their daily life breast cancer survivors with lymphedema have few alternatives but to use a compressive sleeve. Concerned with the well-known low compliance to the daily use of traditional sleeves, we conducted a comparative study in a subgroup of our patients with lymphedema secondary to breast cancer treatment for the subjective assessment of PRADEX®, an innovative class 1 compression sleeve. Secondarily, we aimed to assess the non-inferiority of PRADEX® regarding subjective and objective measures of the severity of lymphedema.

We studied 46 women with grade 1 secondary arm lymphedema, who used their usual sleeve and PRADEX® daily for 2 weeks each, in a crossover design.

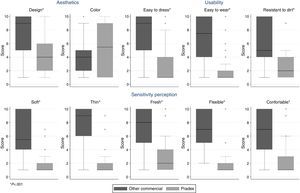

The new therapeutic sleeve was classified as having a better design and a better usability and comfort (more comfortable, thinner, fresher, softer, more flexible, comfortable, resistant to dirt and easier to dress and to wear). Women's subjective opinion about the severity of lymphedema favored their usual sleeve in detriment of PRADEX®, but this subjective feeling was contradicted by objective measurements of different perimeters of the arm at the beginning and at the end of the study.

We concluded that the PRADEX® sleeve, not being worse in its compressive therapeutic efficacy, is much better with regard to patient comfort.

Arm lymphedema secondary to treatment is the most feared late iatrogenic side effect for long-term survivors of breast cancer, with a negative impact on patient's self-image and quality of life and usually irreversible.1,2 The incidence reported in numerous publications is extremely variable, from 6% to 80%.3,4 A 25–30% incidence should serve as a basis for benchmarking in quality-assurance at Breast Units.5,6

The huge paradigm shift in the axillary approach of breast cancer created by the sentinel node biopsy in the last 20 years, and even the most recent randomized trials in which radiotherapy emerges as an alternative to an axillary clearance after a positive sentinel node, kept the lymphedema incidence as a cornerstone in the analysis of axillary morbidity.7–9

A careful approach to arm lymphedema secondary to breast cancer treatment remains up-to-date by the increasing number of longer survivals as well as the recent achievements in axillary treatment.1,5,7,9 The decongestive lymphedema therapy should be multimodal, involving skin care, manual massage, rehabilitation arm exercises, compression elastic sleeves or intermittent pneumatic compression and associated with a personalized careful explanation of preventive measures and psychosocial support to patients.1,3,4,10 However, high quality evidence on the individual effectiveness of preventive or therapeutic attitudes is scarce.2,5,11

In their daily life breast cancer survivors with lymphedema have few alternatives but to use a compressive elastic arm sleeve, an unpleasant, tough, hot, very poorly tolerated and socially stigmatizing garment. The proportion of patients with lymphedema reporting the use of a compression garment is lower than 30%.5 Concerned with the well-known low compliance to the daily use of traditional compression sleeves, we conducted a comparative study in patients with lymphedema secondary to breast cancer treatment for the subjective assessment of PRADEX®, a new compression therapeutic sleeve designed to overcome previous usability limitations of commercially available sleeves. Secondarily, we aimed to assess the non-inferiority of PRADEX® regarding subjective and objective measures of the severity of lymphedema.

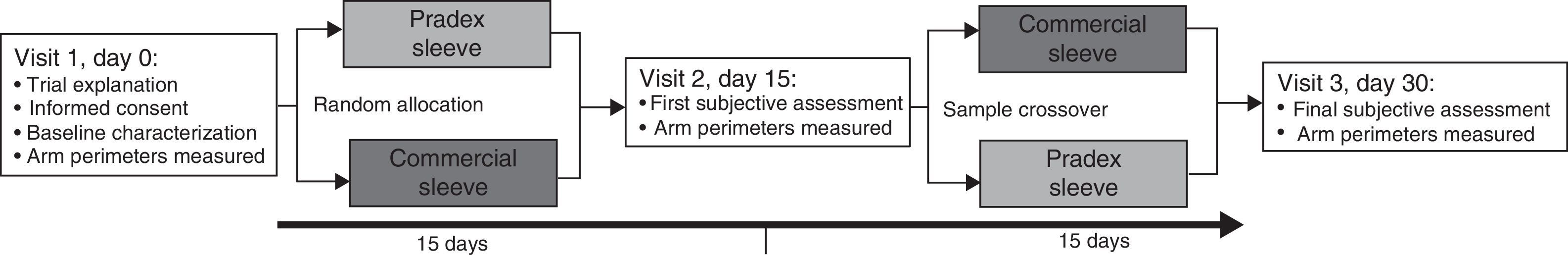

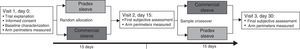

MethodsTrial designThe study has a crossover design with two experimental series of sequential treatment and comparator, and random allocation of patients at initial treatment.

Sample selectionThe study sample included women with grade 1 arm lymphedema due to axillary surgery and/or radiotherapy for breast cancer treatment, with wrist circumference 170–230mm, who already used a compression class 1 sleeve on a daily basis, prescribed in our institution by a physiatrist and provided by the hospital free-of-charge, as a technical aid.

From a total of 71 patients of our database registered as having lymphedema grade 1 and to whom a compressive sleeve was prescribed, 22 women were excluded at initial recruitment: 3 had already died, 1 was in a terminal stage, 5 never used the prescribed sleeve, 4 progressed in lymphedema severity, 7 could not be reached and finally 2 refused to participate. After the beginning of the study, 3 more women were excluded for not fulfilling the established times for the use of sleeves, defined below. Finally, 46 women had available data for analysis.

Study settingsFig. 1 illustrates the study design. Two breast nurses of Breast Center of Centro Hospitalar São João interviewed personally all 46 women. In the first visit an initial interview was made to explain the trial and start the first intervention, a second interview was made on day 15 at the time of exchange of the sleeves and a last interview was made at the end of the consecutive second period of 15 days, without any wash out period. Information concerning sociodemographic characteristics, anthropometry, presence of comorbidities and lymphedema characterization were collected. Body mass index (BMI) was measured and categorized according to the standard World Health Organization definition.12 The perimeters of the wrist, forearm and arm were measured, with a tape, at baseline and days 15 and 30. The patients had to record in a written diary the usage time of the sleeves. Satisfaction was assessed by a structured questionnaire applied by nurses. Women were encouraged to make personal suggestions for improving the sleeves used.

OutcomesThe primary outcome was satisfaction with the sleeve, as assessed by 11 items, each measured in a 10-point Likert scale (higher score meaning lower satisfaction), covering esthetics, comfort, usability and static electricity dimensions. Secondary outcomes were subjective assessment of severity of edema and measured upper limb perimeters. All outcomes were assessed at days 15 and 30.

The PRADEX® sleevePRADEX® is an innovative medical device designed for the treatment of upper limb lymphedema secondary to breast cancer treatment, ranked as class 1 according to the Quality Assurance RAL-GZ 387/2 standard Medical Compression Arm Sleeves. This medical device conveys class 1 compression (15–21mmHg), leaving the shoulder sleeveless, and is recommended for patients with wrist perimeters between 170 and 208mm.13–15

PRADEX® sleeve designed to overcome previous usability limitations of commercially available sleeves is produced using double cylinder circular knitting technology, using a 1×1 rib knitted structure. This knitted fabric is composed by two materials: textured multifilament polyamide yarns and elastane filaments covered with multifilament polyamide yarns. The use of these materials, along with the type of loops interlacement, provides a very comfortable medical device keeping the therapeutic performance based on graduated compression. Arm sleeves have been tested, according to established international standards, for properties related to usability, comfort and compression performance.14,15

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using the statistical software Stata 11.0 (College Station, TX, 2009). Sample characteristics are presented as counts and proportions for all categorical variables and median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to compare median differences between paired observations for continuous variables. Differences between categorical variables were computed using the McNemar test. A p-value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

EthicsThe study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Centro Hospitalar São João and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Financial support was offered to patients to cover the expenses related with hospital visits. At the end of the trial the new sleeve was offered to patients.

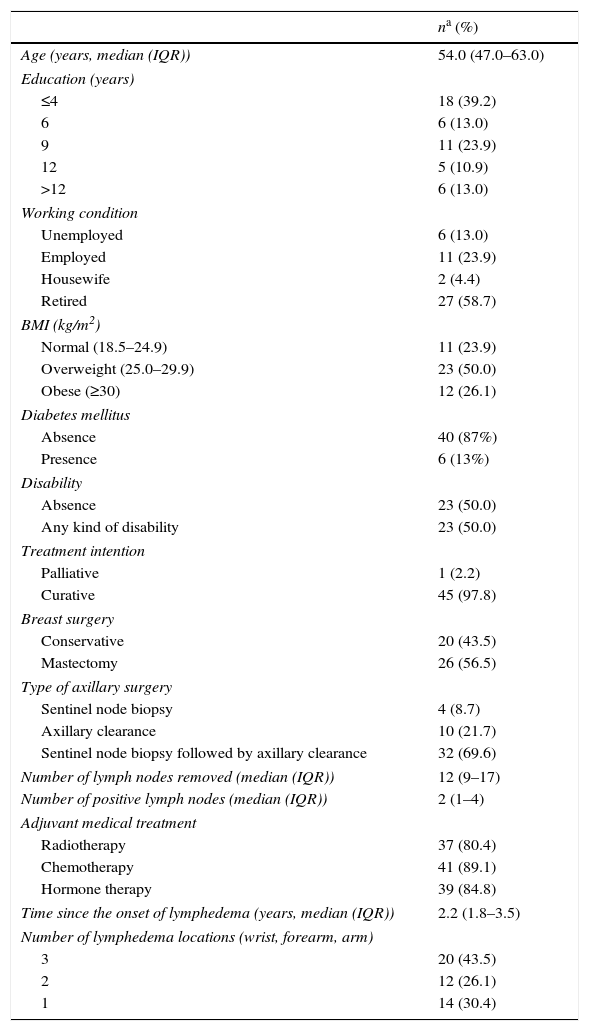

ResultsThe patient's characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median (IQR) age of women was 54.0 (47.0–63.0) years and more than a third had up to four years of education. Almost a quarter of women were employed during the study period and more than a half were retired. Concerning comorbidities contributing to the risk of lymphedema, 50.0% were overweight, 26.1% were obese and 13.0% reported to have diabetes. Half of women presented some degree of physical disability.

Patients’ characteristics (n=46).

| na (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years, median (IQR)) | 54.0 (47.0–63.0) |

| Education (years) | |

| ≤4 | 18 (39.2) |

| 6 | 6 (13.0) |

| 9 | 11 (23.9) |

| 12 | 5 (10.9) |

| >12 | 6 (13.0) |

| Working condition | |

| Unemployed | 6 (13.0) |

| Employed | 11 (23.9) |

| Housewife | 2 (4.4) |

| Retired | 27 (58.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 11 (23.9) |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 23 (50.0) |

| Obese (≥30) | 12 (26.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Absence | 40 (87%) |

| Presence | 6 (13%) |

| Disability | |

| Absence | 23 (50.0) |

| Any kind of disability | 23 (50.0) |

| Treatment intention | |

| Palliative | 1 (2.2) |

| Curative | 45 (97.8) |

| Breast surgery | |

| Conservative | 20 (43.5) |

| Mastectomy | 26 (56.5) |

| Type of axillary surgery | |

| Sentinel node biopsy | 4 (8.7) |

| Axillary clearance | 10 (21.7) |

| Sentinel node biopsy followed by axillary clearance | 32 (69.6) |

| Number of lymph nodes removed (median (IQR)) | 12 (9–17) |

| Number of positive lymph nodes (median (IQR)) | 2 (1–4) |

| Adjuvant medical treatment | |

| Radiotherapy | 37 (80.4) |

| Chemotherapy | 41 (89.1) |

| Hormone therapy | 39 (84.8) |

| Time since the onset of lymphedema (years, median (IQR)) | 2.2 (1.8–3.5) |

| Number of lymphedema locations (wrist, forearm, arm) | |

| 3 | 20 (43.5) |

| 2 | 12 (26.1) |

| 1 | 14 (30.4) |

BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

Almost all patients were treated with curative intention with the exception of one woman submitted to palliative treatment. Mastectomy was performed in 56.5%, while the remaining underwent a conservative surgery. All patients were submitted to axillary surgery: 8.7% underwent only a sentinel node biopsy, 21.7% underwent directly an axillary clearance and the remaining 69.7% were submitted first to a sentinel node biopsy followed by an axillary clearance in the same operative time, after intraoperative verification of the pathological positivity of the sentinel node. The median (IQR) number of axillary lymph nodes removed was 12.5 (9.0–17.0) and the median (IQR) number of axillary positive nodes was 2 (1–4). More than 80% of women underwent adjuvant medical treatment or radiotherapy. The median (IQR) time since the onset of lymphoedema was 2.2 (1.8–3.5) years and in 54.4% of patients it affected the dominant right arm. Almost half of the patients had the lymphedema involving the whole upper limb.

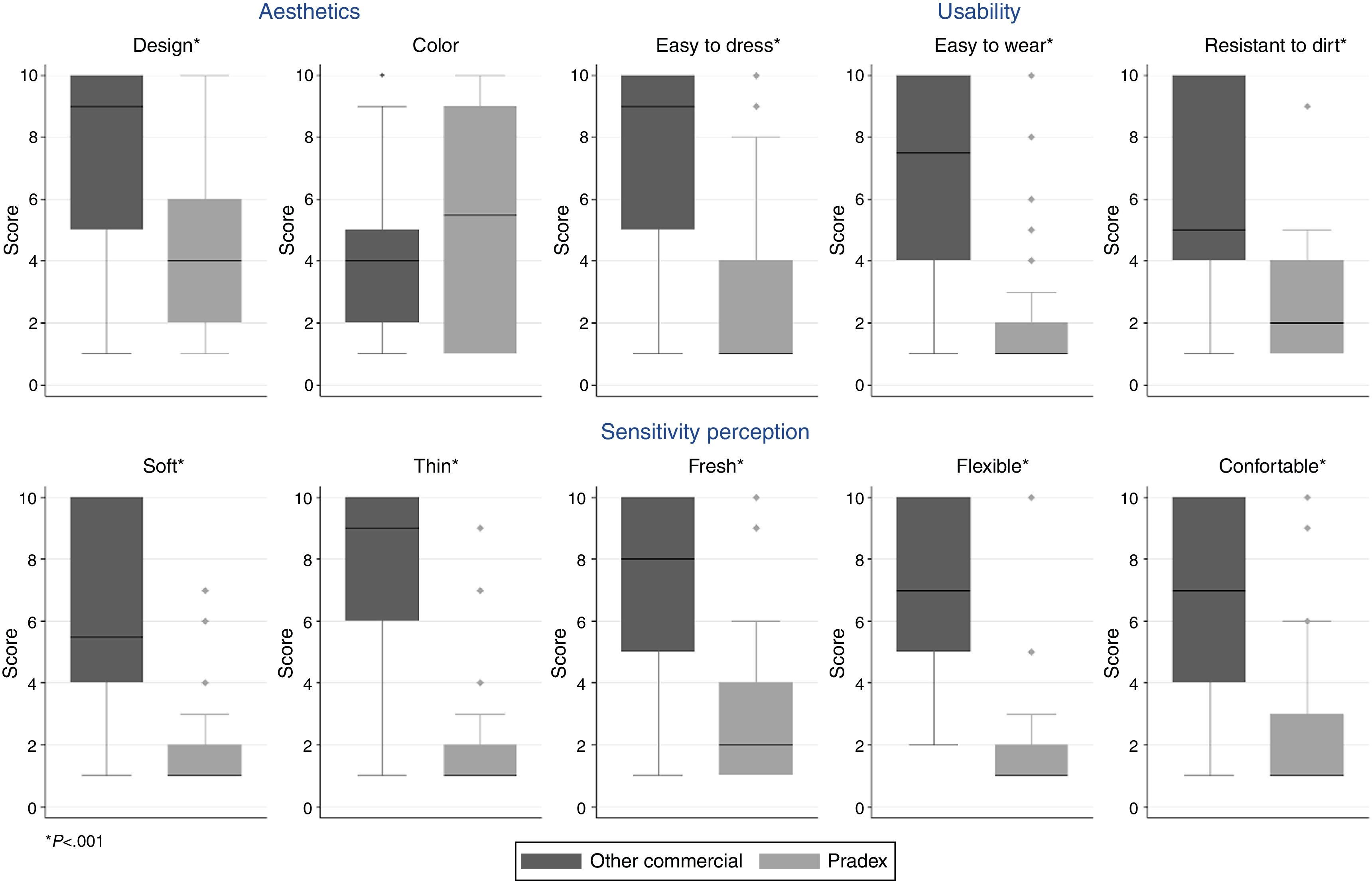

Fig. 2 displays the median values of ten items that measured satisfaction with each sleeve, aggregated in 3 different dimensions. Regarding the dimension that covers the 5 items about sensitivity perception, the new sleeve was softer, thinner, fresher, more flexible and comfortable (all p<0.001). Similarly, the new therapeutic sleeve was classified as having a better design (p<0.001), but no differences were found regarding satisfaction with color (p=0.220). Also, patients recognized that the new sleeve was more practical, being easier to dress, to wear and more resistant to dirt (all p<0.001). Concerning static electricity, this characteristic was not pointed out as a problem for the majority of the patients in both sleeves. However, in the usual sleeve, the spectrum of answers presented a wide range of choices [median (IQR):1 (1–5)], which contrast with the new sleeve for which all patients except one chose the best possible classification [median (IQR):1 (1–1)].

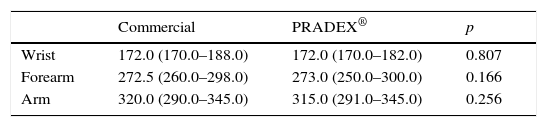

As show in Table 2 very similar measured perimeters of the wrist, forearm and arm were obtained after using PRADEX® and the previous usual sleeve [mean (SD) difference between sleeves: +0.2 (3.5), p=0.807; +0.5 (9.0), p=0.166; −1.6 (10.3), p=0.256, respectively]. Nevertheless, women's subjective evaluation favored their usual sleeve in detriment of PRADEX® (p=0.002).

Perimeters of the arm at different levels after the use of each sleeve.

| Commercial | PRADEX® | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrist | 172.0 (170.0–188.0) | 172.0 (170.0–182.0) | 0.807 |

| Forearm | 272.5 (260.0–298.0) | 273.0 (250.0–300.0) | 0.166 |

| Arm | 320.0 (290.0–345.0) | 315.0 (291.0–345.0) | 0.256 |

The data presented are median (interquartile range) in mm. p values estimated by the Wilcoxon paired-sample test.

Additionally, patients were encouraged to make suggestions for both sleeves and 93% and 87% of our sample proposed alterations in the usual and PRADEX® sleeves, respectively. Interestingly, three patients had no suggestions for improvement because they were fully satisfied with their usual sleeve and nine felt the same about the PRADEX® sleeve. The main suggestions for improvement of their usual sleeve consisted on the removal of the shoulder or bra fastening tapes (35 women), a more flexible and soft mesh (15 women), the removal of the hand and fingers part of the sleeve (13 women) and a cooler tissue (12 women). Regarding the PRADEX® sleeve, the main suggestions for improvement were an interior silicon band for better grip to the upper arm (27 women) and the possibility of a sleeve with different levels of compression at different levels of the arm's length (11 women). Likewise it was suggested that the PRADEX® color should be more similar to skin color (13 women) or to be able to have several colors or patterns to match clothing (10 women).

DiscussionThe scarce published information on usability and especially on the effectiveness of elastic compression sleeves as part of the therapeutic multimodal approach of secondary arm lymphedema2,5,11 limited a sustained choice in clinical daily practice and stimulated the fulfillment of this comparative study of a new and innovative compression arm sleeve.

Our crossover study design with two comparative series of sequential treatment of 15 days each with a daily written record of usage times was designed to avoid a systematic difference if there were a trend for favorable or unfavorable impression with a new device compared to the previous known and unpleasant sleeve, and to allow sufficient time for the women to evaluate each sleeve regarding the 11 subjective parameters defined as primary endpoints. A wash-out period was not considered since it would have no clinical impact on the subjective assessment made by women accustomed to wear a compressive sleeve daily. The continuous monitoring of the patients during the study by the nursing team allowed a rigorous monitoring of compliance, which led to the exclusion of 3 patients who did not meet the established times.

Our results clearly showed that with the exception of the color parameter, our patients preferred the PRADEX® sleeve for all evaluated subjective outcomes. It has a better design, easier to wear and dress, more resistant to dirt, softer, thinner, fresher, more flexible and more comfortable. The PRADEX® sleeve in its first pre-commercial presentation was dark brown in color, hence the high percentage of suggestions for color change is no surprise. One of the future developments is the possibility of customization of color, to combine with everyday clothing. The majority of patients expressed unequivocally that they felt better control of their lymphedema with her usual sleeve, probably because they are accustomed to a more rigid and compressive external device, but this subjective feeling was contradicted by objective measurement of different perimeters of the upper arm done by our nursing team at the beginning, on day 15 and at the end of the study.

The study made very clear the importance of a multidisciplinary support not only from the physiatry team but also from the nurses of a Breast Unit.5,16–18 This was evident with the finding that 5 women in a group of 71 who had been prescribed a compressive sleeve by a physiatrist and offered for free as technical assistance have never even used it, because they did not know how to wear it before the contact with the nursing team. There was wide adherence and cooperation of our patients to the proposed trial, as well as their eagerness to further training support from our breast nurses on the use of compression sleeve and preventive measures to minimize their lymphedema. Almost all patients made suggestions to improve the old sleeve, making it clear that the majority of our patients do not like to use her usual compressive garment. The main improvement suggestion in both sleeves was about its fixation on upper arm, by removing the fastening tapes alternatively using a silicone band within the sleeve so as to prevent rolling of the sleeve. The second criticism to their usual sleeve was the aggressive, tough, rough and warm texture, suggesting a more pleasant, soft and cool tissue that offers PRADEX® sleeve. Another desire expressed by our patients was to have a different compression at different points of the upper limb, which goes in accordance to what is under development in the PRADEX® sleeve. The great number and variety of suggestions for improvement made by the patients will contribute to further research and industrial development.

The major limitation of our study was the small sample size, collected only from a unique center, but with the future commercialization of PRADEX® sleeve it will be possible to further validate it.

ConclusionOur study confirms the better design, usability and comfort of the new therapeutic sleeve over the traditional ones. The PRADEX® sleeve, while not being worse in its compressive therapeutic efficacy, is much better with regard to patient comfort and in our opinion should be preferred.

Conflicts of interestA writing protocol between the hospital board, the hospital ethics committee and the textile company Barcelcom© was done and includes a defined financial support for the hospital. The compressive sleeves PRADEX® used was offered to the participants free of charge at the end of the trial. There was no financial support to any author for the manuscript writing.