Plasma cell leukaemia (PCL) is a rare and aggressive disease. Diagnosis is made when there are >2000/#mL circulating plasma cells in peripheral blood or plasmacytosis >20% of total leukocyte count. We report a case of a 51-year old man with generalized bone pain and constitutional symptoms. Blood peripheral smear revealed leukocytosis with 39% plasma cells. Bone marrow biopsy showed plasma cell invasion, which confirmed the diagnosis of PCL. Additionally, the patient had markers of advanced disease. Chemotherapy with vincristine, adriamycin and dexamethasone was started. Despite an initial favourable response, the patient died 2 months later due to an infectious complication. PCL has no established treatment and has a dismal prognosis, requiring the achievement of better data to improve the disease course.

Plasma cell leukaemia (PCL) is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by malignant proliferation of plasma cells in bone marrow and concomitant peripheral blood involvement.1 It has an estimated incidence of approximately 4 cases/10000000 persons/year, accounting for 1.3–3.4% of all plasma cell discrasias.1 To standardize criteria for this diagnosis, Kyle et al.2 proposed an absolute plasma cell count >2000/#mL or plasma cells comprising >20% of the total white cell count in peripheral blood. PCL is classified as primary when it occurs in the absence of a prior history of multiple myeloma (MM) or secondary when it is related to refractory or relapsing disease.3 Clinical presentation is characterized by nonspecific symptoms1 and median age at diagnosis is usually above 50 years.3 PCL is an extremely aggressive pathology with unsatisfactory response to therapy and poor prognosis with a median survival of 7 months in the primary form and 2 months when it is secondary.4 To date, most publications are based on case reports and series that rarely exceed 20 cases; therefore, the definition of biological, clinical, and prognostic features of the disease remains challenging.1 Therapy is generally based on expert opinion, extrapolation from results obtained in patients with MM, single case reports or small retrospective studies.4 Therapeutic options vary widely and include vincristine, adriamycin and dexamethasone (VAD) or melphalan based regimens. New therapeutic armamentaria with proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, immunomodulatory drugs and stem cell transplantation were recently introduced.3

The authors report a case of a primary PCL treated with the VAD regimen.

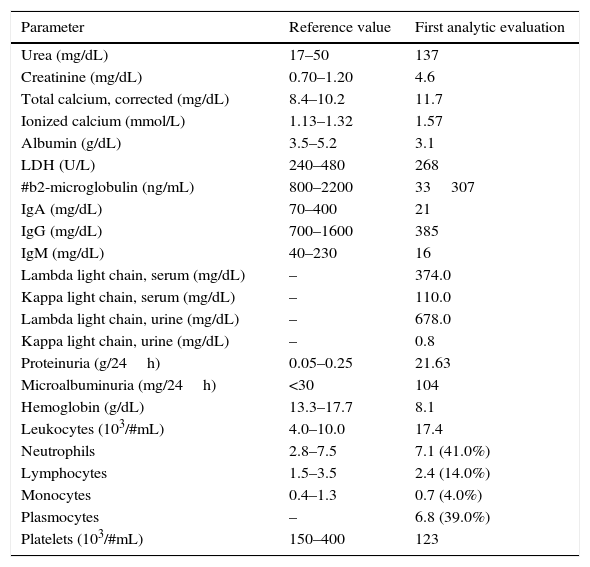

Case reportA 51-year old man with no significant past medical history presented with generalized bone pain, fatigue and >10% weight loss in the previous month. Physical examination was unremarkable with the exception of bone pain at palpation of lumbar column, ribs and hips. Laboratory investigation (Table 1) revealed acute kidney failure and macrocytic anaemia. Peripheral blood smear showed leukocytosis with 39% (6.800/#mL) plasma cells.

Patient's analytic results.

| Parameter | Reference value | First analytic evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Urea (mg/dL) | 17–50 | 137 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.70–1.20 | 4.6 |

| Total calcium, corrected (mg/dL) | 8.4–10.2 | 11.7 |

| Ionized calcium (mmol/L) | 1.13–1.32 | 1.57 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5–5.2 | 3.1 |

| LDH (U/L) | 240–480 | 268 |

| #b2-microglobulin (ng/mL) | 800–2200 | 33307 |

| IgA (mg/dL) | 70–400 | 21 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 700–1600 | 385 |

| IgM (mg/dL) | 40–230 | 16 |

| Lambda light chain, serum (mg/dL) | – | 374.0 |

| Kappa light chain, serum (mg/dL) | – | 110.0 |

| Lambda light chain, urine (mg/dL) | – | 678.0 |

| Kappa light chain, urine (mg/dL) | – | 0.8 |

| Proteinuria (g/24h) | 0.05–0.25 | 21.63 |

| Microalbuminuria (mg/24h) | <30 | 104 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.3–17.7 | 8.1 |

| Leukocytes (103/#mL) | 4.0–10.0 | 17.4 |

| Neutrophils | 2.8–7.5 | 7.1 (41.0%) |

| Lymphocytes | 1.5–3.5 | 2.4 (14.0%) |

| Monocytes | 0.4–1.3 | 0.7 (4.0%) |

| Plasmocytes | – | 6.8 (39.0%) |

| Platelets (103/#mL) | 150–400 | 123 |

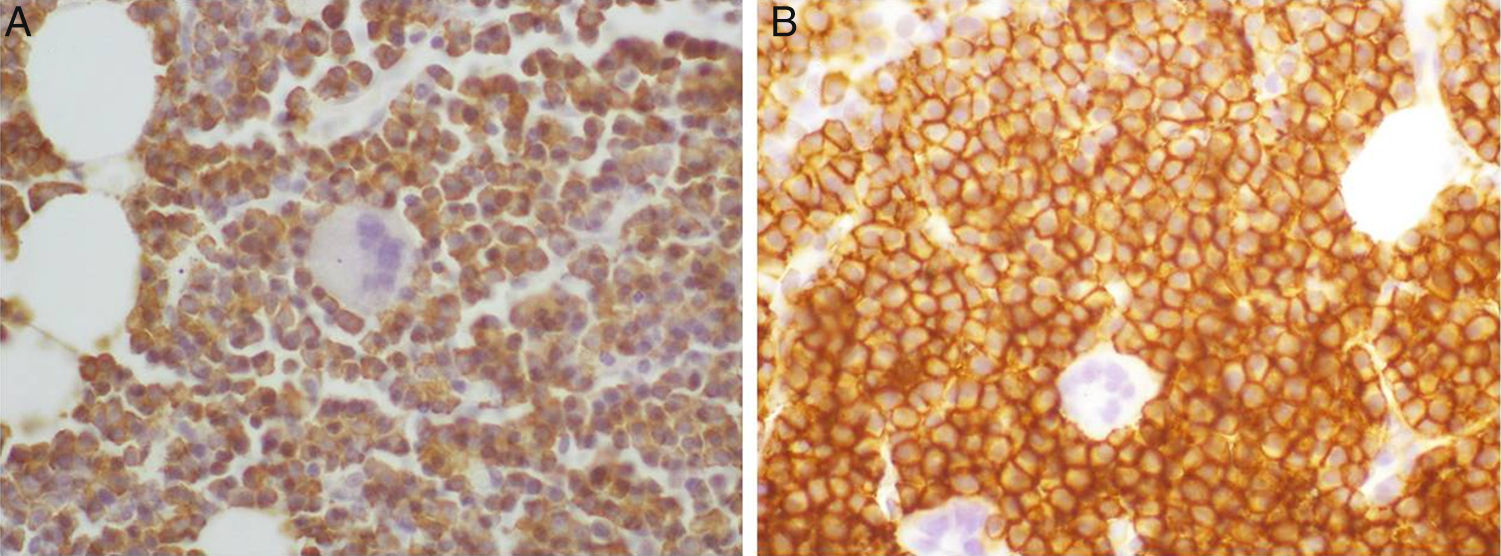

The core biopsy presented hypercellular bone marrow with plasma cell invasion (90% of the total population). The immunohistochemistry study of cells exhibited CD56 and CD138 expression and cytoplasmic lambda light chain restriction (Fig. 1).

Plasma cell karyotype was normal and FISH analysis revealed 12% positivity for del(13) and 48% positivity for t(11;14). Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated a discrete monoclonal spike at gamma globulin level, identified as free lambda chain on immunofixation. An additional analytic study showed hypercalcemia, hypoalbuminemia, elevated #b2-microglobulin, hypogammaglobulinemia and Bence–Jones proteinuria (Table 1). A skull X-ray demonstrated the characteristic “punched out” lesions of MM. Thorax, abdomen and pelvis CT scan revealed multiple osteolytic lesions in vertebral column, ribs and hips.

Secretory PCL diagnosis in stage III of the International Staging System was made. Support therapy with fluids, bisphosphonates, corticosteroids and diuretics was initiated, with normalization of calcium and creatinine levels. Chemotherapy with VAD was begun with the intention to later perform an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Despite initial favourable hematologic response to chemotherapy, the patient died 2 months after diagnosis with nosocomial pneumonia.

DiscussionPrimary PCL is a rare disease characterized by a very aggressive course and an unfavourable prognosis.1,3

Although MM and PCL have an identical malignant plasma cell of origin and share some clinical characteristics (such as age, gender, incidence of extramedullary disease and type of paraprotein secreted by the neoplastic cells), primary PCL has distinct presenting features, response to chemotherapy and prognosis.4 The classic adverse prognostic factors seen in advanced aggressive MM are usually encountered at presentation in primary PCL.5 Therefore, greater awareness and early recognition of the characteristic blood smear can be determinant in correctly diagnosing and initiating appropriate therapy.

Our patient presented several markers of poor prognosis (hypoalbuminemia, elevated #b2-microglobulin, renal insufficiency and hypercalcemia), suggesting the aggressive nature of the disease. Skeletal survey evidenced multiple osteolytic bone lesions, which that can be present in primary PCL but is usually more common in secondary PCL.2,5 In general, primary PCL patients have a higher incidence of extranodal presentation, hypercalcemia and renal dysfunction,2,5 all of which occurred in our patient. Renal failure occurs in up to 50% of patients with MM and several factors contribute to this, including myeloma cast nephropathy, hypercalcemia, light chain deposition, amyloidosis, hyperuricemia, recurrent infections and drug toxicity (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and bisphosphonates).6 Since renal dysfunction can jeopardize the chance of a cancer patient to receive optimal treatment, the identification and correction of potential acute renal failure reversible causes is essential.

The surface immunophenotype of plasma cells in PCL, either primary or secondary, is typically similar to bone marrow plasma cells in MM. However, in a high proportion of PCL patients (up to 80%), plasma cells lack the aberrant CD56 expression, which has led some authors to consider the absence of CD56 as a hallmark of PCL that could distinguish it from MM.7 The expression of CD56, present in our patient, may indicate that the immunophenotype is not a pathognomonic finding or may suggest that, in some cases, PCL results from MM evolution.

FISH analysis revealed del(13) and t(11;14), both already described in the context of MM.8 Del(13) is related with a worse prognosis, while t(11;14) appears to confer better survival and response to treatment in MM patients. Perhaps this translocation can have a different role in PCL, stimulating proliferation, as in the case of mantle cell lymphoma.

Due to the rarity of PCL, no prospective randomized trials investigating treatment have been done. The principle of therapy is achievement of complete remission with induction chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplant. Multiple chemotherapy regimens have been tried with a variable degree of success. Regarding old standards of care, VAD therapy appears to be superior to melphalan.9 The effect of immunomodulatory drugs has been disappointing with thalidomide and experience with lenalidomide is small, not allowing for any conclusions yet. The novel agent bortezomib has greatly enhanced the initial response rate, but did not attain the major corresponding improvement in overall survival.10 Our patient had an induced remission with VAD. Unfortunately, he had a common complication, an infection that ceased of precociously the opportunity to receive a stem cell transplant. Susceptibility to bacterial infections is very common and several factors contribute to this: hypogammaglobulinemia (as was documented in our case), circulating regulatory cells that suppress normal antibody synthesis, abnormalities in complement function and drugs with immunosuppressive effect (ex. dexamethasone use in our patient).

The prognosis for primary and secondary PCL is dismal with a median survival of about 2–8 months. The use of novel agents does not overcome the negative prognosis of PCL as compared with MM, and more research is needed, not only in terms of available therapies, but also for identifying specific molecular pathways responsible for the neoplastic transformation of PCL cells.

ConclusionIn summary, we describe a case of primary PCL with a short unfavourable outcome that illustrates the importance to increase our knowledge of this rare and highly deadly entity, to permit better evaluation and treatment of these patients.

Conflicts of interestNo conflict of interests was declared by the authors.