We are currently witnessing the decline of acute diseases and the emergence of chronic degenerative diseases.

In Portugal, the cumulative effect of the reduction in mortality and birth rates has resulted in an ageing population. The ageing population will create in the medium term a new dynamic of recruitment in various sectors, including health.

With increased life expectancy, the care of chronically ill has become an important area in the context of health services, since they need to be increasingly more focused on the need to provide palliative rather than curative care.

Rationalization of resources must be a goal so that waste is minimized. The present model of palliative care ceases to respond to the pressing needs.

What to do, to adapt to the changes brought by demographic change and by innovation?

What models should be adopted for better resource optimization in palliative care?

A literature review was carried out, including articles that compared the main differences between hospital and home care.

Portugal has a multi-sectoral palliative care model, in light of what happens in reference countries, however, a better rationalization of resources will be required in order to ensure optimization in the distribution of patients.

We also conclude that there is a gap between the patient's will and what is recommended.

To respect the individual preferences of the patient, it is necessary to develop quality home-based palliative care services, focusing on training and the expansion of field teams.

With increasing life expectancy, due to better living conditions and better health care, chronic and progressive diseases have increased. At the same time, the family network also changed, women entered the labour market and households became less extensive, all of these factors are reflected in the health system and in the resources needed to address this problematic. Although an increase in units per palliative care teams since 2006 has been observed, this growth is still insufficient to meet the country's needs.1

While healthcare services were initially centered in treating the disease, there is currently an increasing effort directed to the need to provide palliative rather than curative care.2

Palliative care emerged from the need felt by some health professionals to continue to treat incurable cancer patients, because although the goal at this stage was not to cure the disease, there is much to do for their well-being, namely the control of symptoms. Thus, it proves to be necessary to continue to respond to the patients’ problems. Therapeutic abstention does not mean neglect: between abandonment and therapeutic obstinacy, an alternative emerged, palliative care.3

The right to palliative careWho are then, the patients entitled to palliative care? In theory, everyone has the right to palliative care, but it applies especially to the terminally ill, patients with advanced, incurable and progressive diseases, and patients with severe health problems due to associated suffering.4

The National Plan for Palliative Care defines recipients as all those who have no prospect of curative treatment.

Therefore, palliative care cannot be restricted to cancer patients. For ethical reasons of equity, justice and accessibility to health care, palliative care is not determined by the diagnosis, but by the need of the patient, and it is now widely accepted that cancer and non-cancer patients need this type of intervention. The diseases most frequently associated with palliative care are oncological diseases, AIDS, some cardiovascular diseases, rare diseases and, as expected diseases linked with ageing.

The characteristics of these diseases, by their intensity, variability, complexity, and individual and family impacts, are very difficult to resolve, whether in hospital departments or in the National Network of Integrated Continuous Care (NNICC), particularly if there is no specialized intervention.

The target population of this type of care is now much broader and includes:

- a)

People with any acute, severe and life-threatening disease (severe trauma, leukaemia, acute stroke, etc.) where healing and reversibility are realistic goals, but the situation itself, as well as treatment, has undeniably negative effects in the quality of life and suffering of patients and/or families.

- b)

People with progressive chronic diseases (peripheral vascular disease, cancer, kidney or liver failure, advanced heart or lung disease, neurodegenerative diseases, dementia, etc.).

- c)

People with life threatening diseases, who chose not to be treated for the disease or to have support and/or life extension and require this type of care.

- d)

People with chronic and limiting injuries resulting from an accident or other forms of trauma.

- e)

People seriously or terminally ill (dementia, cancer in terminal stages and severely disabling).5

Accordingly there are patients with different needs, and these differences do not focus only on clinical issues. The distinction between the different phases of the disease and the different levels of complexity helps define a more targeted means of operation, more specific to the needs of each patient, but also allows for better allocation of resources.6 For this reason, it becomes important to describe the stages of the disease and the levels of complexity of patients in palliative care.

The Australian National Sub-acute and Non-acute Patient Classification is a classification in which four palliative phases are described, considering the stage of the disease:

- a)

Acute – unexpected development phase of a problem or where there is a significant increase in the severity of existing problems.

- b)

Deteriorating – stage where there is a gradual development of problems, without the need of sudden change in the handling of the situation. They are patients who are not in the phase described next.

- c)

Terminal – phase when death is imminent, a forecast of hours or days (agony), and does not predict acute interventions.

- d)

Stable – phase in which patients are included when they are not in any of the previous phases.

The National Plan for Palliative Care recommends a division of such care in different organizational levels. Currently, the Palliative Care answers in Portugal are provided by the NNICC through the following health care units:

- a)

Palliative Care Unit (PCU) – provides in-patient care, therefore, it is a service specifically designed to treat and take care of palliative patients. The unit can be in a hospital for acute or non-acute care, a ward, or a structure adjacent to the hospital, it can also be completely independent of the hospital's structure. It should always work with an early discharge perspective and transfer to another type of care, unless it is a dedicated “hospice” unit, where patients remain if they want and need, to die.

- b)

Hospital Support Palliative Care Team (HSPCT) – provides palliative care advice and support to the entire hospital structure, including patients, family and caregivers in the hospital environment. It also offers formal and informal training and interconnects with other services inside and outside of the hospital.

- c)

Home Palliative Care Teams – provide care to patients in their home, as well as support to their families and caregivers. Furthermore, they offer advice to family doctors and nurses who provide care at home.5

These units differ, therefore, for the level of complexity of the disease, the interventions applied and the outcomes (mean hospitalization time, mortality, etc.).

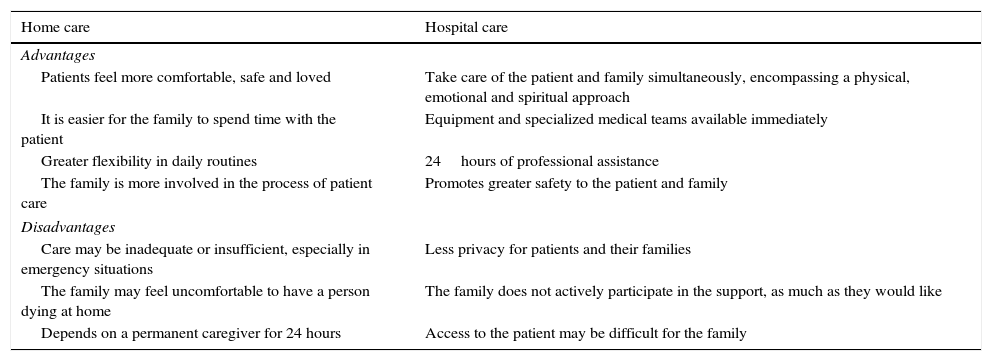

Advantages versus disadvantages of hospital and home models (Table 1)There are two major palliative care models: the home and the hospital. Both models have important advantages and disadvantages. Then, to which model should a health professional refer a patient?

Advantages and disadvantages of home and hospital care models.

| Home care | Hospital care |

|---|---|

| Advantages | |

| Patients feel more comfortable, safe and loved | Take care of the patient and family simultaneously, encompassing a physical, emotional and spiritual approach |

| It is easier for the family to spend time with the patient | Equipment and specialized medical teams available immediately |

| Greater flexibility in daily routines | 24hours of professional assistance |

| The family is more involved in the process of patient care | Promotes greater safety to the patient and family |

| Disadvantages | |

| Care may be inadequate or insufficient, especially in emergency situations | Less privacy for patients and their families |

| The family may feel uncomfortable to have a person dying at home | The family does not actively participate in the support, as much as they would like |

| Depends on a permanent caregiver for 24 hours | Access to the patient may be difficult for the family |

With this study, we intend to briefly reflect and thus help define what would be the best model, or the best strategy to adopt in Portugal in order to meet the emerging needs, particularly with regards to the comparison between home and hospital care.

Thus, government policies should recognize and take into account these concerns. Palliative care requires professionals with specific training and availability. Family Medicine, Internal Medicine or other branches of medicine cannot and should not continue to take on this area of health services, because of the specificity it requires and deserves.

Currently, the training of doctors mainly emphasizes technical aspects, while ethical aspects and communication are undervalued. To cure or to prolong life are the goals of modern medicine while death has come to be seen as a failure. New Medical Training is an indispensable means to change this attitude. Medical schools should start teaching palliative care in undergraduate education, for only this way can the current situation be changed, giving all medical doctors basic training to show them that death exists and that when there is no possibility of cure or life prolongation, there are numerous possibilities of action that can make a decisive difference in how patients live this phase of life and how they die.3

Not only the wider community but also health professionals continue to misinterpret that palliative care is intended “to give affection” to the terminally ill in their final days. Today, it no longer makes sense to continue to think in this manner. Given the available evidence, the recommended model must be based on a perspective of shared care and management of chronic disease. Additionally, it should address all patients with advanced disease and limited prognosis, where the goal is the global relief of suffering, and promotion and comfort and the patient's quality of life, which is justified for weeks, months and sometimes years before the death of the patient. In this context, the training of health professionals is considered, by the scientific community, as the key factor in the successful implementation of an excellent Palliative Care service.7

In Portugal, despite the fact that Palliative Medicine is a competence of the Medical Doctors Association (Ordem dos Médicos) since November 2013, and this constitutes an undeniable breakthrough in this area, it is necessary to continue to join efforts to ensure that health professionals are properly qualified. This step is essential to correct wrong ideas and prejudices, and ensure that palliative care continues to develop in a sustainable manner.8

A study conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit (an American consulting company) revealed that Portugal occupies the 31st position in a ranking of 40 countries with regard to palliative care. The last place belongs to India, and the first to the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia.

Currently, the UK is the country with the highest Palliative Care coverage worldwide, and Palliative Medicine has been a recognized medical specialty since 1987.

Among the main difficulties in implementing palliative care is the lack of training of professionals in palliative treatment, since educational institutions are more focused on curative treatment. Likewise, palliative care is also a recognized medical specialty in Australia, the United States of America (USA) and South Africa, and these are the countries that are at the leading edge when it comes to this kind of care. Despite the variability in organizational responses, the diversity in each country, it seems that answers to the needs of different groups, do not depend on the existence of a single model of palliative care, because they must be adapted to the reality of each country, but on the quality of training in palliative care. This point is crucial for better care, whether they are uni- or multi-sector models and comes across in all studies. In the UK, for example, there is an entity, “Help the Hospice”, which promotes training in palliative care not only in the UK but also promotes international support for the development of hospices all over the world, particularly in developing countries. Monti et al. conducted a retrospective study based on 10 years of experience in palliative care and concluded that for proper monitoring of the patient and family, a better university education and support for continuous training are necessary, regardless of the model.9

In a meta-analysis published in Cochrane in May 2013, 49 systematic reviews were subject to analysis in order to quantify the effect of home-based palliative care for patients and their families when compared with hospital care. For this evaluation, the outcomes considered were: symptom control, quality of life, satisfaction and anxiety of the caregiver. An economic analysis was also included in this study, which includes parameters such as: inpatient length of stay versus time spent in home care, waiting time at hospital admission, absenteeism from work by caregivers, medication and other resources, among others.

At the economic resource level, this study was inconclusive, meaning there were no significant differences when comparing home-based care with hospital care. The study concluded that the main advantages of home-based palliative care are:

- a)

Respect the patients will of wanting to be treated and die at home.

- b)

Decrease symptom burden, without this having a negative impact on caregivers.

There is indeed evidence that over 50% of patients prefer to be treated and die at home.10 However, in most countries, patients see their wish to die at home denied; in Portugal, data from 2005 points to 33%.11

Is the principle of autonomy being violated? The concept of autonomy refers to the perspective that every human being is to be truly free and provided with the minimum conditions for self-realization. Autonomy presumes the principle of freedom of choice. For a person to act autonomously, he or she must receive truthful information, be free from influences that may have some control over him or her, and possess the ability to make thoughtful decisions.12

The possibility of the patient to choose, in a clarified way, the means of diagnosis and the unit providing health care that best suit his or her interests, will be one of the great achievements of our health care system.13

In a study conducted by Tamir, in 2007, terminally ill patients (in the last year of life) receiving specialized treatment at home were evaluated and compared with those who were hospitalized. From an economic perspective, this study found that the savings in home care are greater in the end of life period, and when the period is greater than one year, although not economically efficient, home care satisfies the willingness of patients to die at home. When patients have home care, 80% of them die at home, with their will being fulfilled.14

Chronic diseases produce many symptoms that cause significant distress for patients and this is particularly evident in diseases where treatment is not possible and the main focus is on the control of symptoms. The symptoms experienced by these patients are not presented in isolation, but in clusters. The impact that this set of symptoms has on patients’ life is called a “symptom burden”. This concept includes not only the severity of symptoms, but also how patients perceive the impact these symptoms have on their life. This set of symptoms encompasses: fatigue, muscle and joint pain, chest pain, difficulty sleeping, sexual dysfunction, irritability, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting, constipation, among others. All of these symptoms are highly correlated with depression and may compromise therapy.

These symptoms have very expressively and statistically significant decreases when patients receive palliative care at home instead of at the hospital. This is the great advantage of home-based palliative care, as shown by the article: “Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their care givers”.

A study from 2004 conducted in Florida, with 382 patients, found that pain control in home care is easier. It also found that patients are less likely to have periods of exacerbation and remain hospitalized in intensive care units, and this aspect is further reflected in a lower cost to the health system.10

The model adopted by Portugal demonstrates accessibility and equity, but the need to grow has become evident, particularly in the area of home-based palliative care. Many patients with severe chronic, incurable and progressive diseases in need of palliative care continue to occupy hospital beds, in departments without the necessary specialized training in pain management for the patient and/or family and sometimes patients are subjected to therapeutic obstinacy. Diagnostic and therapeutic obstinacy are diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that are disproportionate and useless in the global context of an individual patient without providing any benefit accruing to it, and may even cause increased suffering.

Prolonged hospitalizations, with high associated costs, require that an optimization of hospital vacancies be carried out, especially in the current socio-economic situation that the country is facing.

Optimization can only be achieved with an appropriate referral of the patient to the most suitable structures to monitor the patient and usually with a lower cost than hospital admissions; these may include his or her home, units or rehabilitation centres, or the network of continuing or palliative care,. Hongdao et al. argues that the referral to home care should be early, as it reflects a greater good for the patient, but also a lower cost.10

The treatment of most patients in their homes contributes to lower costs, as suggested by data from studies conducted in other countries. Several studies show that the use of palliative care allows significant savings in spending on health, especially in the last month of life where it can reach 25–40%. These data contradict the fear of increased costs with the implementation of palliative care. This fear is probably the biggest obstacle to palliative care development. The Community Support Teams in Palliative Care (CSTPC) are therefore essential and need to be implemented on the ground.

In Australia, for example, a study was conducted which concludes that due to a correct referral, there was a decrease in the number of admissions to acute services and an increase in home care, and this resulted in savings of $160,000 per year.

A study comparing home and hospice care, taking into account an economic perspective, concluded that it is in the last months of life that more benefits are obtained when a patient is at home to receive care, namely:

- a)

In the last month of life, specialized support at home saves 31–64% of the costs.

- b)

In the last six months, expert support at home saves 15%.

- c)

After one year, home care costs are 12% higher.

Although the authors concluded that it is not economically advantageous to receive home care lasting more than one year, the quality of end of life and the quality of life of caregivers is greater when patients receive support at home and the number of hospital readmissions is lower.

Furthermore, according to the National Health Service (UK), home care in 2005 saved about 150 million euros by freeing hospital beds and the amount spent on this type of care represents a reduction of 300 million euros in hospital budgets.15

In the USA, a Hospital Palliative Care Team demonstrated a savings of $4800 per patient when palliative care models were implemented at home. This reduction in costs is due, according to the study, to a reduction in hospital admissions and the number of visits to emergency rooms, and an increase in the number of patients dying at home.16

Also in the USA, a study undertaken between 2002 and 2004 by the Hospital Palliative Care Teams, also corroborated savings of $4908 per patient, not only due to a decrease in admissions and visits to the emergency, but likewise a decrease in the consumption of drugs and performance of diagnostic tests.9

It might be thought that the reality of the American health system does not compare with the Portuguese one. However, if the current European situation is examined, specifically Spain, the same conclusions can be observed. In Catalonia, the implementation of a palliative care model, with different organizational levels as those discussed above, has shown a decrease of 3000 euros per patient.17

ConclusionsFaced with the progressive ageing of the population and the increasing prevalence of disabling chronic diseases, it is successively more difficult to respond to the many health needs, particularly with the current network of continued and integrated care services nationwide still being very scarce.

With the financial and economic crisis that Portugal is currently undergoing, society is forced to further ponder on the rationalization of resources, optimization and service efficiency, while continuing to witness the low political priority through not planning a health system for the medium- and/or long-term and a public policy focused on the short-term.

As can be concluded from the data presented in the discussion, all studies point to evidence that when teams are equipped with the necessary skills, the rationalization of resources is better, with clear advantages for patients and their families.

With this work, we observed that there is already an adequate network of Palliative Care in Portugal, which has three different levels of complexity. This model is advocated by Australia, the UK and the USA; countries that are at the forefront of palliative care. Considering this, what is the difference? Since the Portuguese model is multi-sectoral, there appear to be gaps in the distribution of patients by different sectors and thus, there are patients who could be in home care, where costs are lower, that are using hospital services. In 2009, the average daily cost of a patient in the integrated continued care network was 81 euros per day, with an average daily value in hospitalization of 403 euros per day. Why does this happen? Perhaps this allocation of resources should be done through a more appropriate strategic plan. That is, palliative care should be recognized as a specific area, with very specialized training, oriented to this area of work. With greater knowledge, it would be possible to optimize the distribution of patients. Another reason for some patients to stay in hospitals rather than in their home, may be that the home support teams are scarce and their training is still not enough to make it possible for patients to receive the same quality as the hospitals’ staff offer, given their greater experience. For these two reasons, training is essential in this process, and it is the main difference between Australia, the UK, the USA and Portugal, where the model is essentially the same. It should not be overlooked that in these countries, palliative care has been a recognized medical speciality since the 80s. Consequently, palliative care excellence is only possible with specific training.

Another very important aspect of this study is the patient's will. More than 50% of patients want to be treated and die at home, and in Portugal, 33% of them do not see their desire respected.12

Doctors and other health professionals have a duty to respect the autonomy of the patient, allowing him or her to receive the care they actually want, and that death occurs on site and in the company of who the patient chooses.18

Admittedly, palliative care should determine the most appropriate treatment depending on the circumstances, with the goal of providing the patient and family conditions to have a good quality of life. Quality of life is only fully achieved when the patient's aspirations are respected. In this context, palliative care should be directed to the patient and not the disease.

In short, when the wish of the patient is to be treated at home and this choice is a plausibility, then this should be respected because, properly prepared teams can secure the highest quality of life until the end, even at home.

Conflicts of interestNo conflict of interests was declared by the authors.