In recent decades, there has been an increase in extrapulmonary TB (EP-TB) rates in industrialized countries with a low incidence of tuberculosis (TB), especially among specific foreign-born population groups. The aim of this study was to describe sociodemographic, epidemiological, microbiological, clinical and treatment characteristics of EP-TB cases and associated risk factors in Spain.

MethodsWe performed a descriptive, retrospective, multi-center observational study of new TB cases in different regions in Spain (Comunidades Autónomas, CCAA) between 2006 and 2014. We used logistic regression and calculated odd ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to determine EP-TB-associated factors.

ResultsThe proportion of EPTB were higher among the foreign-born population (22.1%) than among native Spaniards (15.9%; p=0.001). Foreign cases were mostly Asian, with up to 42.8% of India-Pakistan cases showing some form of EP-TB. The factors related were: immigrant status (OR:1.62; CI:1.35–1.95); age >50 years; (OR:1.70; CI:1.36–2.13); diagnosis delay of >51 days (OR:1.38; CI:1.17–1.62); co-infection with HIV (OR:1.77; CI:1.21–2.55); negative smear sputum microscopy (OR:3.01; CI:2.50;3.61); negative culture; (OR:8.1; CI:6.57–10.02); poor clinical progression during disease progression (OR:2.93; CI:1.30–6.39).

ConclusionsWe detected a high percentage of EP-TB forms in the foreign-born population, mostly in Asian people. Special attention should be devoted to the diagnosis of EP-TB in these groups. Other measures required include increased clinical suspicion and improved microbiological diagnosis to support earlier and adequate treatment.

En las últimas décadas se ha producido un aumento de las tasas de tuberculosis extrapulmonar (TBEP) en los países industrializados con baja incidencia de tuberculosis (TB), especialmente en grupos específicos de población de origen extranjero. El objetivo de este estudio fue describir las características sociodemográficas, epidemiológicas, microbiológicas, clínicas y del tratamiento de los casos de TBEP en España y los factores de riesgo asociados.

MétodosRealizamos un estudio observacional descriptivo, retrospectivo y multicéntrico de los nuevos casos de TB en diferentes regiones de España (comunidades autónomas [CC. AA.]) entre 2006 y 2014. Utilizamos la regresión logística y calculamos las odds ratio (OR) y el intervalo de confianza (IC) del 95% para determinar los factores asociados a la TBEP.

ResultadosLa proporción de TBEP fue mayor entre la población nacida en el extranjero (22,1%) que entre los españoles nativos (15,9%; p=0,001). Los casos extranjeros eran en su mayoría asiáticos; el 42,8% de los casos procedentes de India-Pakistán mostraban algún tipo de TBEP. Los factores relacionados fueron: situación de migrante (OR: 1,62; IC 95%: 1,35-1,95); edad >50 años (OR: 1,70; IC 95%: 1,36-2,13); retraso en el diagnóstico de >51 días (OR: 1,38; IC 95%: 1,17-1,62); coinfección con VIH (OR: 1,77; IC 95%: 1,21-2,55); examen microscópico de frotis de esputo negativo (OR: 3,01; IC 95%: 2,50-3,61); cultivo negativo (OR: 8,1; IC 95%: 6,57-10,02); mala evolución clínica durante la progresión de la enfermedad (OR: 2,93; IC 95%: 1,30-6,39).

ConclusionesDetectamos un alto porcentaje de formas TBEP en la población nacida en el extranjero, principalmente en personas asiáticas. Debe prestarse especial atención al diagnóstico de TBEP en estos grupos. Otras medidas requeridas incluyen una mayor sospecha clínica y un mejor diagnóstico microbiológico para apoyar un tratamiento temprano y más adecuado.

According to estimates from the World Health Organization, 10 million people became ill with tuberculosis (TB) in 2017, and 1.3 million people died as a result1. This shows that TB continues to be an important, unresolved public health issue that causes an unacceptable level of mortality, especially considering that it is a treatable, preventable disease.

Since the pulmonary form is the most common, and its epidemiological surveillance has been the priority for the control of disease transmission, there have been limited studies and publications to date on extrapulmonary forms (EP-TP). Evidence regarding the risk factors of EP-TB is scarce, as is knowledge on TB among immigrants and its differential features in this population group. In Spain, the Program for Tuberculosis Research (PII-TB), created by the Spanish Society for Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR), has undertaken several studies to identify the distinctive features of cases among immigrants in our country2.

Several publications in Spain, the United States and the United Kingdom have shown that the clinical form of TB is changing 3–10, with a year-on-year increase in the rate of EP-TB, mostly in the immigrant population. EP-TB proportion now reaches almost 50% of all TB cases in some ethnic groups8–10. Diagnosing the forms of TB-EP requires a high initial clinical suspicion and can be complicated due to the difficulty in obtaining microbiological samples. The symptoms and signs can be nonspecific and many times, the chest-x-ray can be normal and the sputum smear negative. For this reason, the delay in diagnosis is frequent and can condition an increase in morbidity and mortality.

The objective of this study was to describe sociodemographic, epidemiological, microbiological and clinical variables associated with the various forms of TB and the factors associated with EP-TB risk in Spain, such as belonging to specific foreign-born population groups.

MethodsStudy design and population sampleWe performed a descriptive, retrospective, multi-center observational study of newly diagnosed cases of TB supported by 61 collaborators, mainly respiratory and infectious disease physicians, from 53 hospitals throughout Spain, registered in SEPAR's PII-TB database between January 1st, 2006 and December 31st, 2014.

Inclusion criteriaThe following inclusion criteria were applied: (a) a positive sputum smear test, or a negative one with a positive culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis; alternatively, in cases of EP-TB, presence of a compatible histology; (b) suspected disease, as a result of clinical, radiological, epidemiological or laboratory evidence, where the physician considered it appropriate to start an antituberculosis treatment regime.

DatabasePatient follow-up was performed according to the previously defined evaluation calendar included in the PII-TB.

The information obtained was prospectively recorded in an electronic data collection logbook (DCL) via a computer application accessible only by PII-TB researchers through a website requiring a personalized ID and password. Survey and database compliance were monitored by phone calls and e-mails between the principal investigator and collaborators.

Study variablesWe analyzed the following variables: (a) TB presentation forms, encoded in three categories depending on the site of disease, namely pulmonary (affecting the lung and the tracheobronchial tree), extrapulmonary (non-pulmonary presentation including pleural tuberculosis) and disseminated TB (miliary TB, affecting two or more organ systems or showing positive blood culture). Cases with both pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB were considered pulmonary TB11; (b) sociodemographic data (age; gender; country of birth; working status; history of tobacco, alcohol and other drugs use); (c) associated conditions (HIV; other immune system depression, such as chemotherapy); (d) anamnesis (history of anti-tuberculosis treatment; time when the symptoms and signs first appeared); (f) diagnosis (date when diagnosis tests were required; TB site; sputum smear microscopy; culture; radiology; susceptibility to drugs, classification according to a pattern of resistance in MDR-TB, defined as a form of TB that is resistant to both isoniazid and rifampicin); (g) treatment (regime; treatment starting date; treatment termination date; adherence to treatment; directly observed treatment); (h) clinical and radiological progression (improvement; stability; disease progression, defined as a situation in which the expected improvement in clinical and/or microbiological and/or radiological progression is not attained or is halted after following and adhering to the proper treatment); (i) final outcome (recovery, treatment completed, failure, moving out, withdrawal, death caused by TB, death due to any other cause, time of death, treatment prolongation, loss to follow-up).

Statistical analysisWe performed a descriptive study of the variables of interest, calculating frequency distributions for qualitative variables, and measures of central tendency and precision for quantitative variables. At the bivariate level, we assessed possible relationships between the various forms of TB and each variable of interest by comparing proportions between groups using the χ2 test. At multi-variate level, we fit a logistic regression model using a backward method to select variables found to be associated in the bivariate analysis (p≤0.05). We calculated odd ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), and tested model fitting using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. A p≤0.05 value was considered statistically significant for all analyses, and all analyses were carried out using SPPS software, version 23.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL USA) and R statistical package, version 3.2.4 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

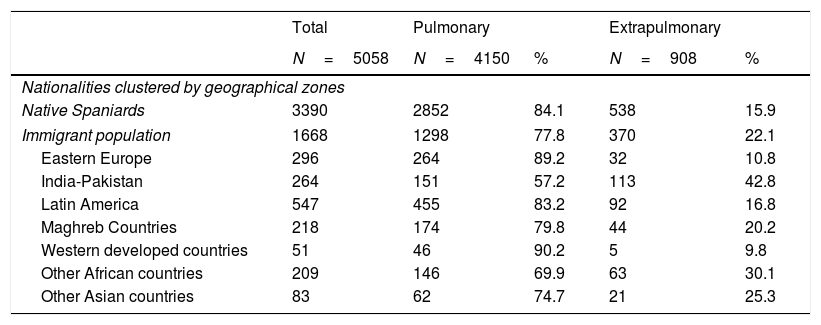

ResultsThe PII-TB database contained 5058 registered cases of TB corresponding to the study period, of which 908 (17.9%) had EP-TB. The percentage of EP-TB was higher among the foreign-born population (22.1%) than among native Spaniards (15.9%; p<0.001). We also observed differences according to country of origin, with EP-TB forms being more prevalent in immigrants from India-Pakistan (42.8%), other Asian countries (25.3%), Maghreb countries (20.2%), other African countries (30.1%) and Latin America (16.8%). The proportion tended to be lower in individuals from Eastern Europe (10.8%) and Western developed countries (9.8%) (Table 1).

Presentation forms of tuberculosis cases according to geographical zones of origin, 2006–2014.

| Total | Pulmonary | Extrapulmonary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=5058 | N=4150 | % | N=908 | % | |

| Nationalities clustered by geographical zones | |||||

| Native Spaniards | 3390 | 2852 | 84.1 | 538 | 15.9 |

| Immigrant population | 1668 | 1298 | 77.8 | 370 | 22.1 |

| Eastern Europe | 296 | 264 | 89.2 | 32 | 10.8 |

| India-Pakistan | 264 | 151 | 57.2 | 113 | 42.8 |

| Latin America | 547 | 455 | 83.2 | 92 | 16.8 |

| Maghreb Countries | 218 | 174 | 79.8 | 44 | 20.2 |

| Western developed countries | 51 | 46 | 90.2 | 5 | 9.8 |

| Other African countries | 209 | 146 | 69.9 | 63 | 30.1 |

| Other Asian countries | 83 | 62 | 74.7 | 21 | 25.3 |

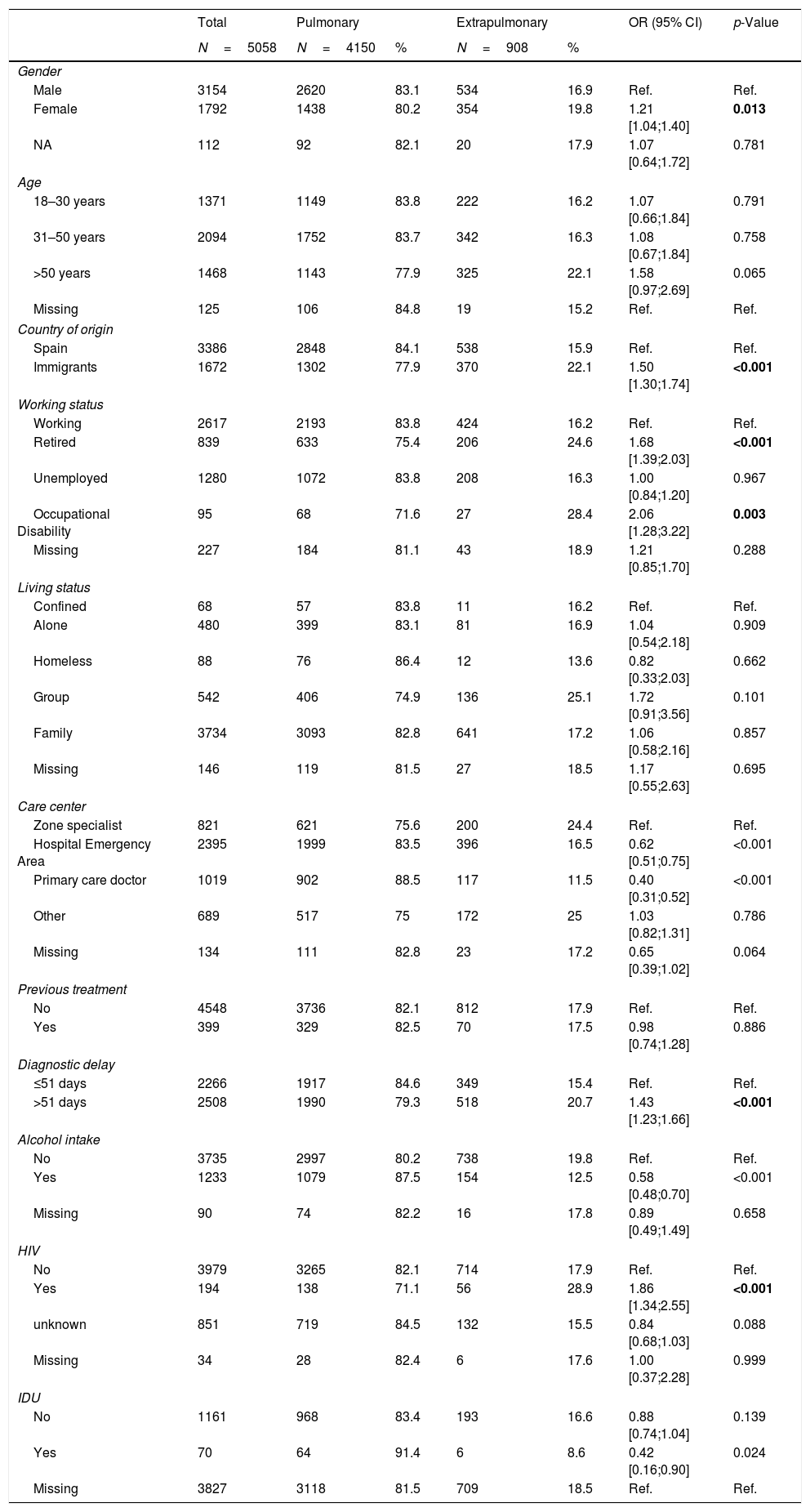

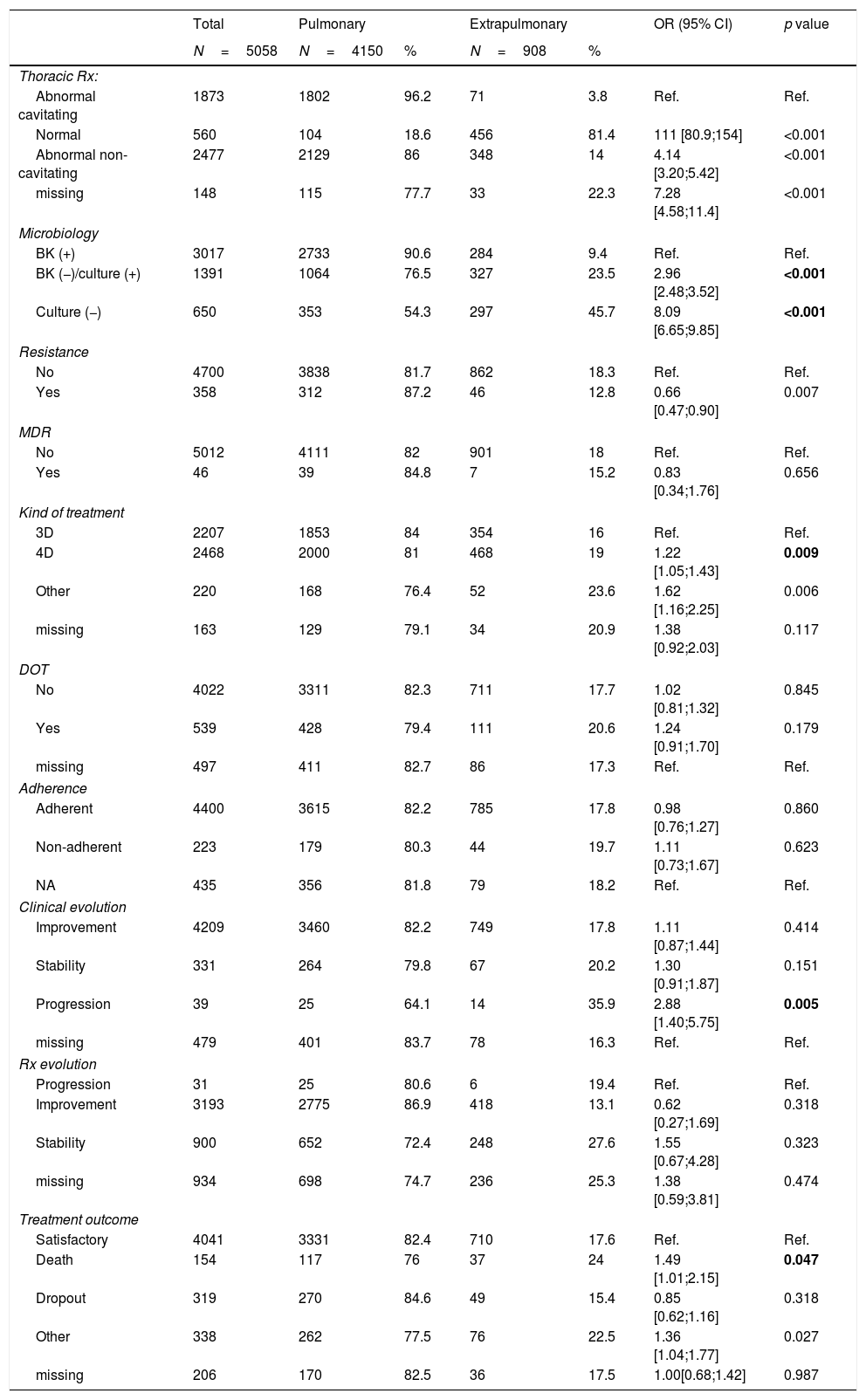

Sociodemographic, epidemiological, microbiological and clinical features of pulmonary TB and EP-TB cases are described in Tables 2 and 3. Our descriptive analysis showed a higher proportion of EP-TB than pulmonary TB in women, immigrants, patients older than50 years, patients with a delay in diagnosis of over 51 days (median days from onset of symptoms to initiation of treatment12), and people co-infected with HIV. In addition, most patients with EP-TB showed a negative sputum smear test and culture, and lower resistance to some antituberculosis drugs. We found no statistically significant differences in the proportion of pulmonary and EP-TB among cases of multi-drug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). A higher proportion of EP-TB cases were treated with 4 drugs rather than 3, and EP-TB cases also showed more disfavourable disease progression and had higher risk of dying as a result of their disease.

Sociodemographic and epidemiological features of all pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis cases (total number of patients: 5058), 2006–2014.

| Total | Pulmonary | Extrapulmonary | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=5058 | N=4150 | % | N=908 | % | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 3154 | 2620 | 83.1 | 534 | 16.9 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Female | 1792 | 1438 | 80.2 | 354 | 19.8 | 1.21 [1.04;1.40] | 0.013 |

| NA | 112 | 92 | 82.1 | 20 | 17.9 | 1.07 [0.64;1.72] | 0.781 |

| Age | |||||||

| 18–30 years | 1371 | 1149 | 83.8 | 222 | 16.2 | 1.07 [0.66;1.84] | 0.791 |

| 31–50 years | 2094 | 1752 | 83.7 | 342 | 16.3 | 1.08 [0.67;1.84] | 0.758 |

| >50 years | 1468 | 1143 | 77.9 | 325 | 22.1 | 1.58 [0.97;2.69] | 0.065 |

| Missing | 125 | 106 | 84.8 | 19 | 15.2 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Country of origin | |||||||

| Spain | 3386 | 2848 | 84.1 | 538 | 15.9 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Immigrants | 1672 | 1302 | 77.9 | 370 | 22.1 | 1.50 [1.30;1.74] | <0.001 |

| Working status | |||||||

| Working | 2617 | 2193 | 83.8 | 424 | 16.2 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Retired | 839 | 633 | 75.4 | 206 | 24.6 | 1.68 [1.39;2.03] | <0.001 |

| Unemployed | 1280 | 1072 | 83.8 | 208 | 16.3 | 1.00 [0.84;1.20] | 0.967 |

| Occupational Disability | 95 | 68 | 71.6 | 27 | 28.4 | 2.06 [1.28;3.22] | 0.003 |

| Missing | 227 | 184 | 81.1 | 43 | 18.9 | 1.21 [0.85;1.70] | 0.288 |

| Living status | |||||||

| Confined | 68 | 57 | 83.8 | 11 | 16.2 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Alone | 480 | 399 | 83.1 | 81 | 16.9 | 1.04 [0.54;2.18] | 0.909 |

| Homeless | 88 | 76 | 86.4 | 12 | 13.6 | 0.82 [0.33;2.03] | 0.662 |

| Group | 542 | 406 | 74.9 | 136 | 25.1 | 1.72 [0.91;3.56] | 0.101 |

| Family | 3734 | 3093 | 82.8 | 641 | 17.2 | 1.06 [0.58;2.16] | 0.857 |

| Missing | 146 | 119 | 81.5 | 27 | 18.5 | 1.17 [0.55;2.63] | 0.695 |

| Care center | |||||||

| Zone specialist | 821 | 621 | 75.6 | 200 | 24.4 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Hospital Emergency Area | 2395 | 1999 | 83.5 | 396 | 16.5 | 0.62 [0.51;0.75] | <0.001 |

| Primary care doctor | 1019 | 902 | 88.5 | 117 | 11.5 | 0.40 [0.31;0.52] | <0.001 |

| Other | 689 | 517 | 75 | 172 | 25 | 1.03 [0.82;1.31] | 0.786 |

| Missing | 134 | 111 | 82.8 | 23 | 17.2 | 0.65 [0.39;1.02] | 0.064 |

| Previous treatment | |||||||

| No | 4548 | 3736 | 82.1 | 812 | 17.9 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 399 | 329 | 82.5 | 70 | 17.5 | 0.98 [0.74;1.28] | 0.886 |

| Diagnostic delay | |||||||

| ≤51 days | 2266 | 1917 | 84.6 | 349 | 15.4 | Ref. | Ref. |

| >51 days | 2508 | 1990 | 79.3 | 518 | 20.7 | 1.43 [1.23;1.66] | <0.001 |

| Alcohol intake | |||||||

| No | 3735 | 2997 | 80.2 | 738 | 19.8 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1233 | 1079 | 87.5 | 154 | 12.5 | 0.58 [0.48;0.70] | <0.001 |

| Missing | 90 | 74 | 82.2 | 16 | 17.8 | 0.89 [0.49;1.49] | 0.658 |

| HIV | |||||||

| No | 3979 | 3265 | 82.1 | 714 | 17.9 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 194 | 138 | 71.1 | 56 | 28.9 | 1.86 [1.34;2.55] | <0.001 |

| unknown | 851 | 719 | 84.5 | 132 | 15.5 | 0.84 [0.68;1.03] | 0.088 |

| Missing | 34 | 28 | 82.4 | 6 | 17.6 | 1.00 [0.37;2.28] | 0.999 |

| IDU | |||||||

| No | 1161 | 968 | 83.4 | 193 | 16.6 | 0.88 [0.74;1.04] | 0.139 |

| Yes | 70 | 64 | 91.4 | 6 | 8.6 | 0.42 [0.16;0.90] | 0.024 |

| Missing | 3827 | 3118 | 81.5 | 709 | 18.5 | Ref. | Ref. |

HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; IDU: Injected drug users; missing: Not answered.

Ref. Variable data used as a reference for analysis.

Radiological, microbiological and progression of all pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis cases in a 5058-patient cohort, 2006–2014.

| Total | Pulmonary | Extrapulmonary | OR (95% CI) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=5058 | N=4150 | % | N=908 | % | |||

| Thoracic Rx: | |||||||

| Abnormal cavitating | 1873 | 1802 | 96.2 | 71 | 3.8 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Normal | 560 | 104 | 18.6 | 456 | 81.4 | 111 [80.9;154] | <0.001 |

| Abnormal non-cavitating | 2477 | 2129 | 86 | 348 | 14 | 4.14 [3.20;5.42] | <0.001 |

| missing | 148 | 115 | 77.7 | 33 | 22.3 | 7.28 [4.58;11.4] | <0.001 |

| Microbiology | |||||||

| BK (+) | 3017 | 2733 | 90.6 | 284 | 9.4 | Ref. | Ref. |

| BK (−)/culture (+) | 1391 | 1064 | 76.5 | 327 | 23.5 | 2.96 [2.48;3.52] | <0.001 |

| Culture (−) | 650 | 353 | 54.3 | 297 | 45.7 | 8.09 [6.65;9.85] | <0.001 |

| Resistance | |||||||

| No | 4700 | 3838 | 81.7 | 862 | 18.3 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 358 | 312 | 87.2 | 46 | 12.8 | 0.66 [0.47;0.90] | 0.007 |

| MDR | |||||||

| No | 5012 | 4111 | 82 | 901 | 18 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 46 | 39 | 84.8 | 7 | 15.2 | 0.83 [0.34;1.76] | 0.656 |

| Kind of treatment | |||||||

| 3D | 2207 | 1853 | 84 | 354 | 16 | Ref. | Ref. |

| 4D | 2468 | 2000 | 81 | 468 | 19 | 1.22 [1.05;1.43] | 0.009 |

| Other | 220 | 168 | 76.4 | 52 | 23.6 | 1.62 [1.16;2.25] | 0.006 |

| missing | 163 | 129 | 79.1 | 34 | 20.9 | 1.38 [0.92;2.03] | 0.117 |

| DOT | |||||||

| No | 4022 | 3311 | 82.3 | 711 | 17.7 | 1.02 [0.81;1.32] | 0.845 |

| Yes | 539 | 428 | 79.4 | 111 | 20.6 | 1.24 [0.91;1.70] | 0.179 |

| missing | 497 | 411 | 82.7 | 86 | 17.3 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Adherence | |||||||

| Adherent | 4400 | 3615 | 82.2 | 785 | 17.8 | 0.98 [0.76;1.27] | 0.860 |

| Non-adherent | 223 | 179 | 80.3 | 44 | 19.7 | 1.11 [0.73;1.67] | 0.623 |

| NA | 435 | 356 | 81.8 | 79 | 18.2 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Clinical evolution | |||||||

| Improvement | 4209 | 3460 | 82.2 | 749 | 17.8 | 1.11 [0.87;1.44] | 0.414 |

| Stability | 331 | 264 | 79.8 | 67 | 20.2 | 1.30 [0.91;1.87] | 0.151 |

| Progression | 39 | 25 | 64.1 | 14 | 35.9 | 2.88 [1.40;5.75] | 0.005 |

| missing | 479 | 401 | 83.7 | 78 | 16.3 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Rx evolution | |||||||

| Progression | 31 | 25 | 80.6 | 6 | 19.4 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Improvement | 3193 | 2775 | 86.9 | 418 | 13.1 | 0.62 [0.27;1.69] | 0.318 |

| Stability | 900 | 652 | 72.4 | 248 | 27.6 | 1.55 [0.67;4.28] | 0.323 |

| missing | 934 | 698 | 74.7 | 236 | 25.3 | 1.38 [0.59;3.81] | 0.474 |

| Treatment outcome | |||||||

| Satisfactory | 4041 | 3331 | 82.4 | 710 | 17.6 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Death | 154 | 117 | 76 | 37 | 24 | 1.49 [1.01;2.15] | 0.047 |

| Dropout | 319 | 270 | 84.6 | 49 | 15.4 | 0.85 [0.62;1.16] | 0.318 |

| Other | 338 | 262 | 77.5 | 76 | 22.5 | 1.36 [1.04;1.77] | 0.027 |

| missing | 206 | 170 | 82.5 | 36 | 17.5 | 1.00[0.68;1.42] | 0.987 |

Rx: Radiography; BK: Bacilloscopy; MDR: Multiple drug resistance; 3D: three drugs; 4D: four drugs; DOT: Directly Observed treatment;missing: Not answered.

Satisfactory (recovery+full treatment); Death (TB-related death and other causes of death); Dropout (dropouts+lost); Others (moving out+failures+treatment extension+others).

Ref.: Variable data used as a reference for analysis.

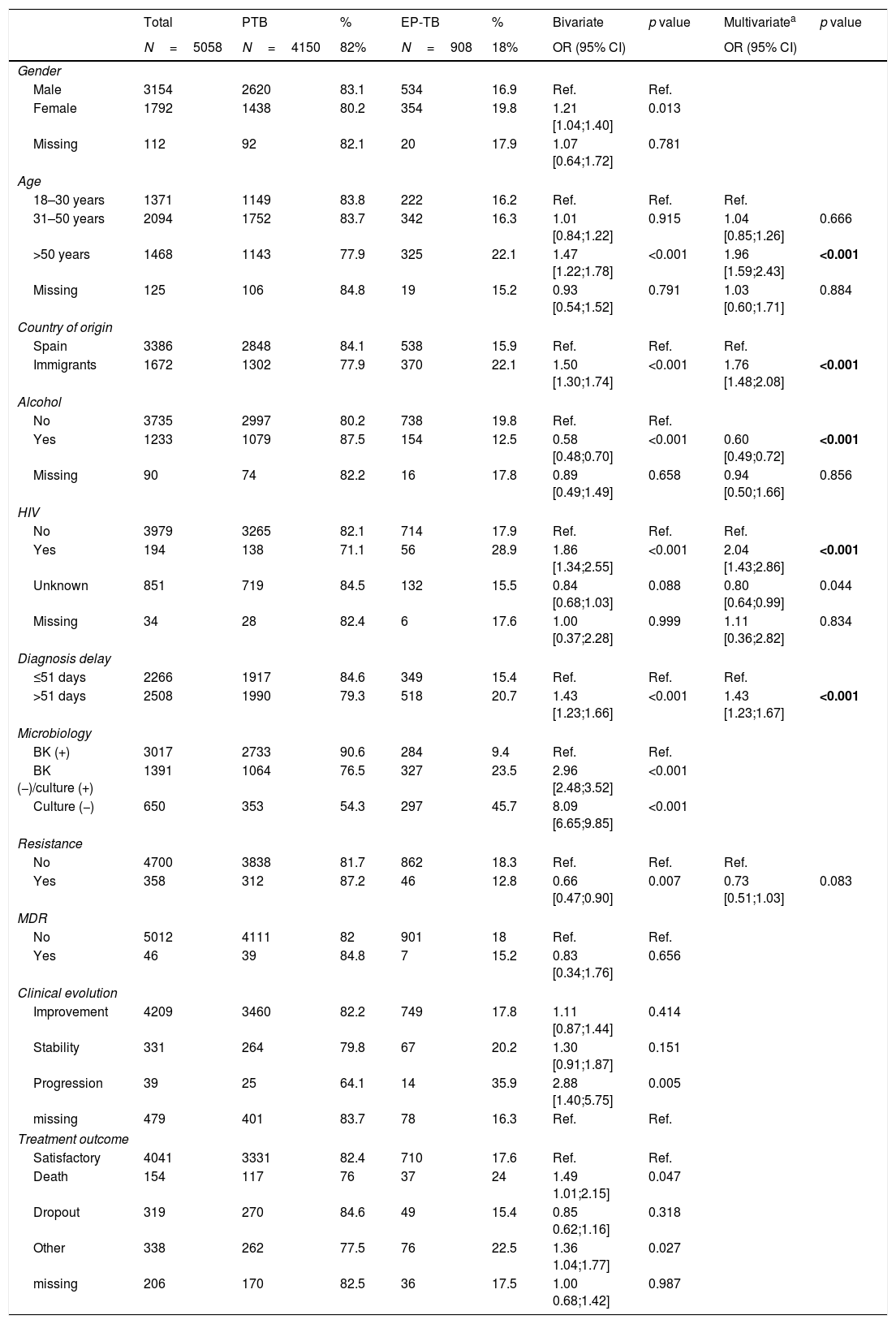

Our multi-variate analysis (Table 4) showed that EP-TB was associated with being older than 50 years, being an immigrant, HIV co-infection, a diagnostic delay of >51 days, a negative smear test, negative culture, and poorer clinical progression toward advancing disease.

Extrapulmonary TB-related factors in a 5058 patient cohort (patients with tuberculosis) in Spain,2006–2014.

| Total | PTB | % | EP-TB | % | Bivariate | p value | Multivariatea | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=5058 | N=4150 | 82% | N=908 | 18% | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 3154 | 2620 | 83.1 | 534 | 16.9 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Female | 1792 | 1438 | 80.2 | 354 | 19.8 | 1.21 [1.04;1.40] | 0.013 | ||

| Missing | 112 | 92 | 82.1 | 20 | 17.9 | 1.07 [0.64;1.72] | 0.781 | ||

| Age | |||||||||

| 18–30 years | 1371 | 1149 | 83.8 | 222 | 16.2 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| 31–50 years | 2094 | 1752 | 83.7 | 342 | 16.3 | 1.01 [0.84;1.22] | 0.915 | 1.04 [0.85;1.26] | 0.666 |

| >50 years | 1468 | 1143 | 77.9 | 325 | 22.1 | 1.47 [1.22;1.78] | <0.001 | 1.96 [1.59;2.43] | <0.001 |

| Missing | 125 | 106 | 84.8 | 19 | 15.2 | 0.93 [0.54;1.52] | 0.791 | 1.03 [0.60;1.71] | 0.884 |

| Country of origin | |||||||||

| Spain | 3386 | 2848 | 84.1 | 538 | 15.9 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Immigrants | 1672 | 1302 | 77.9 | 370 | 22.1 | 1.50 [1.30;1.74] | <0.001 | 1.76 [1.48;2.08] | <0.001 |

| Alcohol | |||||||||

| No | 3735 | 2997 | 80.2 | 738 | 19.8 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 1233 | 1079 | 87.5 | 154 | 12.5 | 0.58 [0.48;0.70] | <0.001 | 0.60 [0.49;0.72] | <0.001 |

| Missing | 90 | 74 | 82.2 | 16 | 17.8 | 0.89 [0.49;1.49] | 0.658 | 0.94 [0.50;1.66] | 0.856 |

| HIV | |||||||||

| No | 3979 | 3265 | 82.1 | 714 | 17.9 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Yes | 194 | 138 | 71.1 | 56 | 28.9 | 1.86 [1.34;2.55] | <0.001 | 2.04 [1.43;2.86] | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 851 | 719 | 84.5 | 132 | 15.5 | 0.84 [0.68;1.03] | 0.088 | 0.80 [0.64;0.99] | 0.044 |

| Missing | 34 | 28 | 82.4 | 6 | 17.6 | 1.00 [0.37;2.28] | 0.999 | 1.11 [0.36;2.82] | 0.834 |

| Diagnosis delay | |||||||||

| ≤51 days | 2266 | 1917 | 84.6 | 349 | 15.4 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| >51 days | 2508 | 1990 | 79.3 | 518 | 20.7 | 1.43 [1.23;1.66] | <0.001 | 1.43 [1.23;1.67] | <0.001 |

| Microbiology | |||||||||

| BK (+) | 3017 | 2733 | 90.6 | 284 | 9.4 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| BK (−)/culture (+) | 1391 | 1064 | 76.5 | 327 | 23.5 | 2.96 [2.48;3.52] | <0.001 | ||

| Culture (−) | 650 | 353 | 54.3 | 297 | 45.7 | 8.09 [6.65;9.85] | <0.001 | ||

| Resistance | |||||||||

| No | 4700 | 3838 | 81.7 | 862 | 18.3 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Yes | 358 | 312 | 87.2 | 46 | 12.8 | 0.66 [0.47;0.90] | 0.007 | 0.73 [0.51;1.03] | 0.083 |

| MDR | |||||||||

| No | 5012 | 4111 | 82 | 901 | 18 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 46 | 39 | 84.8 | 7 | 15.2 | 0.83 [0.34;1.76] | 0.656 | ||

| Clinical evolution | |||||||||

| Improvement | 4209 | 3460 | 82.2 | 749 | 17.8 | 1.11 [0.87;1.44] | 0.414 | ||

| Stability | 331 | 264 | 79.8 | 67 | 20.2 | 1.30 [0.91;1.87] | 0.151 | ||

| Progression | 39 | 25 | 64.1 | 14 | 35.9 | 2.88 [1.40;5.75] | 0.005 | ||

| missing | 479 | 401 | 83.7 | 78 | 16.3 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Treatment outcome | |||||||||

| Satisfactory | 4041 | 3331 | 82.4 | 710 | 17.6 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Death | 154 | 117 | 76 | 37 | 24 | 1.49 1.01;2.15] | 0.047 | ||

| Dropout | 319 | 270 | 84.6 | 49 | 15.4 | 0.85 0.62;1.16] | 0.318 | ||

| Other | 338 | 262 | 77.5 | 76 | 22.5 | 1.36 1.04;1.77] | 0.027 | ||

| missing | 206 | 170 | 82.5 | 36 | 17.5 | 1.00 0.68;1.42] | 0.987 | ||

PTB: Pulmonary Tuberculosis; EP-TB: Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; BK: Bacilloscopy; MDR: Multiple drug resistance; missing: Not answered.

Satisfactory (recovery+full treatment); Death (TB-related death and other causes of death); Dropout (dropouts+lost); Others (moving out+failures+treatment extension+others).

Ref.: Variable data used as a reference for analysis.

Our analysis of the cases registered in SEPAR's PII-TB database during this 8-year study period showed the associated factors with EP-TB.

Industrialized countries with a low TB incidence have experienced increase in the rates of EP-TB, partly because of high immigration from low-income countries with high TB incidence8,10,12,13. The incidence of EP-TB is generally lower than pulmonary TB. According to the WHO's 2016 Global Tuberculosis Report, EP-TB is estimated to account for 15% of the total number of new TB cases worldwide1. However, the proportion of EP-TB cases varies between regions, ranging from 8% in the Western Pacific to 23% in the Eastern Mediterranean. Reports from the European Union have shown marked differences between countries, ranging from 4% in Hungary to 48% in the United Kingdom14,15.

Our study shows that extrapulmonary forms are proportionally more common among the immigrant population, which is consistent with other epidemiological studies from several regions and countries in Europe and in the United States7,11,12,14-16.

Traditionally, risk factors associated with the development of EP-TB include immunodeficiency (such as HIV co-infection17,18), very old age, being female, and being non-white7,18,19. However, little is known about other clinical, epidemiological or even microbiological factors. As shown by several studies20-22, there are also some open questions regarding the association between the phylogenetic lineage of strains from different zones and disease presentation.

There seems to be a direct link with host-related factors, and there are unquestionable classic co-morbidities such as immunocompromising disease and HIV17,23. However, there have to be probably more factors, given that rates of HIV co-infection have become less and less common, both in receiving countries and countries of origin21 (e.g. HIV co-infection was less than 4% in our study).

Analysing the geographical origin of the cases in our study, we found that the highest proportion of EP-TB was among Asian-born patients, particularly those born in South Asia (India-Pakistan). This is consistent with studies from the United Kingdom and Germany11,12. In addition, studies from other Asian regions, such as Saudi Arabia, also reported high incidence of EP-TB24, even though the prevalence of traditional risk factors (such as HIV or alcohol and drug abuse) is decreasing in these regions. This forces us to consider whether other factors could be involved, such as metabolic syndromes or genetic polymorphisms that could interfere immune response. For instance, in this population that has been studied, it has been found that the incidence of consanguinity is up to 67% which may be related to diseases of the immune system23,24.

Regarding gender and age, we found that the incidence of EP-TB was higher among women and people aged >50 years. Similar rates have been found in numerous studies worldwide, including the United States, Germany, Denmark, Benin and Taiwan7,12,16,18,25. These studies found that women were more prone to develop EP-TB than men, particularly in their post-reproductive period16,25. Neither our study nor any of the others has shown a link to bacterial load, virulence or strain resistance, which suggests that there are other specific risk factors that make women and individuals age >50 years more vulnerable to disease, such as hormonal factors.

We observed very low proportion of resistance to one or multiple drugs, and also few cases with MDR-TB strains, both in pulmonary TB and in EP-TB. We did not find statistically significant differences in resistance between these pulmonary and EP-TB forms. This also suggests that the form of disease presentation is more strongly associated with host-related factors than with intrinsic features of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, in terms of resistance or virulence.

In addition, from a clinical point of view, patients with EP-TB are much more difficult to diagnose. These cases frequently require invasive techniques and procedures for microbiological confirmation, resulting in significant diagnosis delay. They also have a worse clinical outcome (statistically significant) with a higher frequency of disease progression and greater risk of TB-associated death 26,27.

The main limitation of this study is the missing data for some important variables, as the high percentage of patients in which the result of HIV or radiological information had not been collected. Other limitation of this study is the lack of information about the exact location of EP-TB, because this information is not collected in our database.

Nevertheless, we believe that the high number of cases collected prospectively by investigators from all over Spain can be considered the main strength of this study.

ConclusionsThe results of our study show a high frequency of EP-TB among several groups, such as immigrants, individuals with HIV, and older people.

Therefore, it is in these groups with high risk of developing extrapulmonary forms, where programs should focus on the research of active cases and in the treatment of latent infection in order to prevent its development.

There are other risk factors clearly related to EP-TB that highlight the importance of increasing clinical suspicion and improving the microbiological and/or histological diagnosis of cases in order to introduce better and earlier treatment regimens, despite of their low infectivity, EP-TB contributes significantly to the total TB load, so increased attention is needed in order to achieve the control and the elimination of the disease.

DeclarationsEthical issues and consent to participateIn accordance with International Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences – CIOMS, Geneva, 1991) and the Spanish Epidemiological Society's recommendations on ethical aspects of epidemiological research, the present study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee a Parc de SalutMarin Barcelona (2015/6072/I). It is also compliant with Spanish guidelines on post authorization observational studies (Orden SA S/3740/2009). All participants gave informed consent for their clinical data to be used in this study. Clinical records were handled confidentially, in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Spanish Personal Data Protection Law 15/1999.

Availability of data and materialsThe datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available if formally requested to the corresponding author

Authors’ contributionLL, TR and JAC conceived of the study, participated in its design, literature search, writing original draft, supervision, project Administration and Funding Acquisition.

The principal authors (LL, TR, JPM, JMG, AO, JA, MC) have taken part in the data collection, data interpretation and Writing – Review & Editing.

MC performed the statistical analysis. The Working Group of Integrated Program of Tuberculosis Research have taken part in the collection of the cases.

FundingThe study was funded by a SEPAR research grant (058/2014).

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no financial or no-financial competing interests.

To all healthcare professionals who collaborated in patient follow-up for this study. To Spanish Society of Pneumology (SEPAR) for funding of the study. To Gavin Lucas and Laura Palmira García Raidó for the help in the translation of the manuscript.

R. Agüero (H Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander); J.L. Alcázar (Instituto Nacional de Silicosis, Oviedo); N. Altet (Unidad Prevención y Control Tuberculosis, Barcelona); L. Altube (H Galdakao, Galdakao); F. Álvarez (H San Agustín, Avilés, Asturias); L. Anibarro (Unidad de Tuberculosis de Pontevedra, Pontevedra); M. Barrón (H San Millán-San Pedro, Logroño); P. Bermúdez (H Regional de Málaga, Málaga); E. Bikuña (H de Zumárraga, Zumárraga); R. Blanquer (H. Dr. Peset, Valencia); L. Borderías (H San Jorge, Huesca); A. Bustamante (H Sierrallana, Torrelavega); J.L. Calpe (H La Marina Baixa, Villajoyosa); J.A. Caminero (Complejo Hospitalario Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria); F. Cañas (H. Insular de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria); F. Casas (H Clínico San Cecilio, Granada); X. Casas (H de Sant Boi, Llobregat); E. Cases (H Universitario La Fe, Valencia); N. Castejón (H Los Arcos. Santiago de la Ribera); R. Castrodeza (H El Bierzo Ponferrada-León, Ponferrada); J.J. Cebrián (H Costa del Sol, Marbella); A. Cervera (H Universitario Dr Peset, Valencia); J. E. Ciruelos (H de Cruces,Guetxo); A.E. Delgado (H Santa Ana, Motril); M.L. De Souza (H Universitario de Vall d’ Hebrón, Barcelona); D. Díaz (Complejo Hospitalario Juan Canalejo, La Coruña); M. Domínguez (H del Mar, Barcelona); B. Fernández (H de Navarra, Pamplona); J. Gallardo (H Universitario de Guadalajara, Guadalajara); M. Gallego (Corporación Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Sabadell); M.M. García Clemente (H Central de Asturias, Oviedo); C. García (H General Isla Fuerteventura, Puerto del Rosario); F.J. García (H Universitario de la Princesa, Madrid); F.J. Garros (H Santa Marina, Bilbao); A. Gort (H Santamaría, Lérida); A. Guerediaga (H Santa Marina, Bilbao); J.A. Gullón (H San Agustín, Avilés, Asturias); C. Hidalgo (H Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Granada); M. Iglesias (H Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander); G. Jiménez (H de Jaén), M.A. Jiménez (H Universitario del Vall d’ Hebrón, Barcelona); J.M. Kindelan (H Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba); J. Laparra (H Donostia-San Sebastián, San Sebastián); I. López (H de Cruces, Guetxo); R. Lera(H. Dr. Peset, Valencia);T. Lloret (H General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia); M. Marín (H General de Castellón, Castellón); X. Martínez Lacasa (H Mutua de Terrasa, Tarrasa); E. Martínez (H de Sagunto, Sagunto); A. Martínez (H de La Marina Baixa, Villajoyosa); J.F. Medina (H Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla); C. Melero (H 12 de Octubre, Madrid); C. Milà (H Universitario del Valle de Hebrón, Barcelona); JP Millet, (Serveis Clínics de Barcelona); I. Mir (H Son Llatzer, Palma de Mallorca); F. Molina (H Modelo); C. Morales (H Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Granada); M.A. Morales (H Cruz Roja Inglesa, Ceuta); A. Moreno (Unidad de Investigación de Tuberculosis, Agencia de Salud Pública de Barcelona, Barcelona); V. Moreno (H Carlos III, Madrid); A. Muñoz (H Regional de Málaga, Málaga); C. Muñoz (H Clínico Universitario de Valencia, Valencia) J.A. Muñoz (H Universitario Central, Oviedo); L. Muñoz (H Reina Sofía, Córdoba); M.Oribe (H Galdakao, Galdakao); I. Parra (H Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar); A. Penas (H Universitario Lucus Augusti, Lugo); J.A. Pérez (H Arnau de Vilanova, Valencia); P. Rivas (H Virgen Blanca, León); J. Rodríguez (H Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Granada); J.Ruiz-Manzano (H Universitario Germans Trías i Pujol, Badalona); J. Sala (H Universitario Joan XXIII, Tarragona); D. Sandel (Unidad de Tuberculosis de Pontevedra, Pontevedra); M. Sánchez (H de Fuerteventura, Fuerteventura);M. Sánchez (Unidad Tuberculosis Distrito Poniente, Almería); P. Sánchez (H del Mar, Barcelona); I. Santamaría (H Txagorritxu, Vitoria); F. Sanz (H General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia); A. Serrano (H Son Llatzer, Palma de Mallorca); M. Somoza (Consorcio Sanitario de Tarrasa, Barcelona);E. Tabernero (H de Cruces, Guetxo); E. Trujillo (Complejo Hospitalario de Ávila, Ávila); E. Valencia (H Carlos III, Madrid); P.Valiño (Complejo Hospitalario Juan Canalejo, La Coruña); A. Vargas (H Universitario Puerto Real, Cádiz); I. Vidal (Complejo Hospitalario Juan Canalejo, La Coruña); R. Vidal (H Vall d’Hebrón, Barcelona); M.A. Villanueva (H San Agustín, Avilés, Asturias); A. Villar (H Vall d’ Hebrón, Barcelona); M. Vizcaya (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete, Albacete); M. Zabaleta (H de Laredo, Laredo); G. Zubillaga (H Donostia-San Sebastián, San Sebastián).