Neuroglia has an essential role in pain perception that goes beyond neuropathic pain and is now considered to play a major role in the processes of sensitization, establishment of chronic pain and nociplasticity. In this intricate process of plasticity and neuroinflammation, there are multiple receptors, one of them the transient receptor potential (TRP) that has different types and subtypes in relation to their amino acids. These receptors vary in each person in relation to their sex, hormonal profile, genetics and age, which may explain the variability in pain perception. There are some treatments that intervene in these receptors and many more are in development, which could become a novel and interesting alternative therapy.

La neuroglia tiene un papel esencial en la percepción del dolor que va más allá del dolor neuropático y actualmente se considera que juega un papel importante en los procesos de sensibilización, instauración del dolor crónico y nociplasticidad. En este intrincado proceso de plasticidad y neuroinflamación existen múltiples receptores, uno de ellos el receptor potencial transitorio (TRP) que tiene diferentes tipos y subtipos en relación con sus aminoácidos. Estos receptores varían en cada persona en relación con su sexo, perfil hormonal, genética y edad, lo que puede explicar la variabilidad en la percepción del dolor. Existen algunos tratamientos que intervienen en estos receptores y muchos más están en desarrollo, lo que podría convertirse en una novedosa e interesante terapia alternativa.

The nervous system is composed of different types of cells.1 Glial cells participate as structural, immunological, metabolic and trophic support cells of the neurons, without actively participating in the process of information transmission.2 These cells account for 80–90% of the cellularity of the central nervous system, and their function is vital for its homeostasis. There are two types of glial cells or neuroglia: macroglia, originating in the ectoderm; within this subgroup are the astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and Schwann cells and the second type is called microglia, whose origin is the monocytes of the spinal cord; therefore, its origin is the mesoderm.3

Microglia have a monocytic origin; therefore, one of their main functions is immunological (phagocytosis and removal of cellular detritus).4 It also performs an important role in the maintenance of neuronal homeostasis, neurogenesis and neuronal plasticity in the adult,5 which is why it has been linked to a variety of neurodegenerative pathologies such as Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, as well as other conditions, such as chronic pain.4

Microglia are usually in an inactive state, but when activated, they have two phenotypes. The M1 phenotype, which is activated when there is an agent of injury (infection, trauma, tissue damage), is due to the proinflammatory stimulus induced by cells of the TH1 immune system.6 This phenotype generates proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, IL-18), which in addition to fulfilling an immunological role, can activate peripheral nociceptors, as well as produce excitability of afferent neurons, generating pain. Additionally, at the level of the dorsal horn of the medulla ipsilateral to the nociceptive stimulus, a phenomenon called microgliosis occurs, which is characterized by hypertrophy, proliferation and morphological changes at this level.6 The M2 phenotype has the opposite action to M1, being anti-inflammatory and vital for recovering homeostasis after the resolution of tissue damage produced by a given agent of injury. This phenotype occurs when there is a stimulus by the cytokines IL-4, IL-10 or IL-13. An imbalance between these two phenotypes M1 and M2, due to persistent tissue damage or chronic systemic inflammatory disease, leads to an increase in the M1 phenotype, which in turn generates sensitization of the nociceptors given a persistent stimulus with these cytokines.6

Macroglia and especially astrocytes have also been involved in the pathogenesis of pain and different neuroinflammatory conditions. The activation pathways are like those of microglia (requiring an agent of injury that induces a pro-inflammatory state), although the timing of activation differs between these two cells.7 Microgliosis occurs rapidly in microglia, and its resolution is relatively fast once the nociceptive stimulus ceases (up to 90 days after resolution of the nociceptive stimulus), while astrocytes, despite being activated almost at the same time as microglia, can take longer to cease their activity even if the nociceptive agent is resolved (up to 6 months after a peripheral nerve injury, and up to 9 months in spinal cord injury).7 This is why they have been related as key cells in the transition between acute and chronic pain.

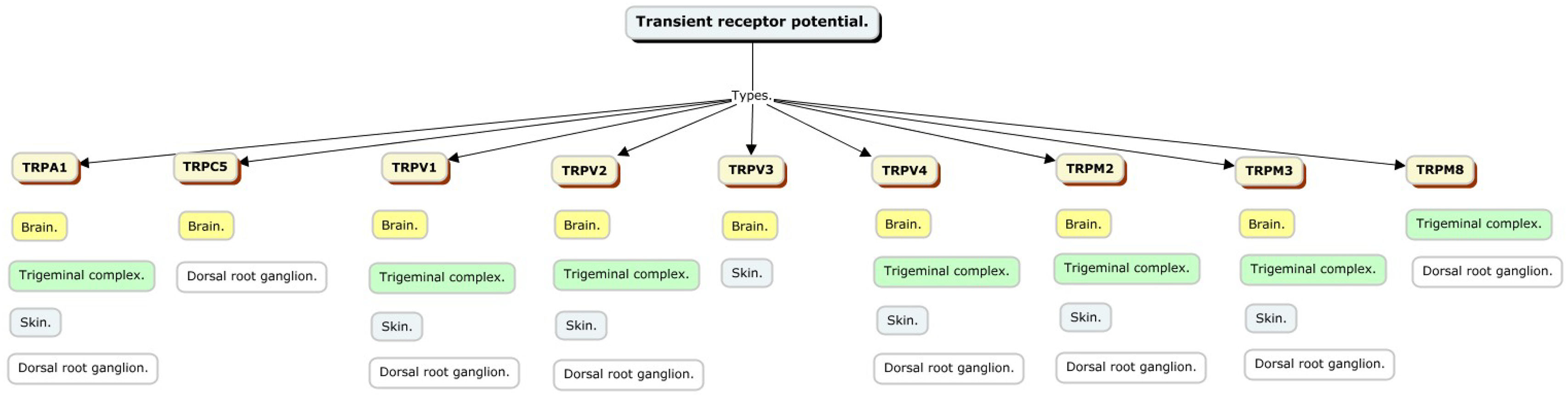

Transient potential receptor characteristicsTransient potential receptors have several subtypes that vary according to the characteristics of their amino acids and can be categorized as: TRPA (Ankyrin), TRPC (Canonical), TRPM (Melastatin), TRPML (Mucolipin), TRPN (NO-mechanical-potential, not found in mammals), TRPP (Policistin), TRPV (Vanilloid),8 and these receptors have different locations and may or may not be involved in pain perception (Fig. 1).

TRPC has seven receptors (TRPC1–7) that conduct cations with variable permeability to monovalent and calcium ions; particularly TRPC1, TRPC4 and TRPC5, are expressed in astrocytes, and expression levels increase with age; they are crucial for intracellular calcium signaling, contributing to calcium transients triggered by stimulation of purinergic and glutamatergic receptors.

TRPVs are essential in sensory perception and cell signaling; have six receptors (TRPV1–6) that respond to various stimuli, including chemical, thermal and noxious signals; are specifically expressed in astrocytes, especially in the cortex and hippocampus; are important for intracellular calcium signaling, crucial for cellular responses, including volume regulation after osmotic shock.

TRPM has eight receptors (TRPM1–8) that are present in different organs including the central nervous system and in turn in the neuroglia. It has an important role in the perception of termination, cell proliferation and depending on the external tissues a role in the perception of pain.

TRPA family includes TRPA1, which is closely linked to the physiology of neuropathic pain, inflammatory nociceptive pain and hereditary pain syndromes. Activation of this receptor generates heat sensation and pain. It is expressed by astrocytes.9

TRPP has three receptors TRPP 2, 3 and 5 which are expressed in the kidney, colon and heart with no relevant role in pain perception or glial cells.

TRPML has three receptors TRPML 1, 2 and 3 that are present in brain, skeletal muscle and bone, with no clear role in pain, but a possible involvement in neurodegenerative disorders.

General considerations of transient potential receptors in painThe activation of neuroglia plays an essential role in the genesis and perpetuation of neuropathic and chronic pain. Among the mechanisms involved in this activation, the interaction with TRP involved in nociception and pain transmission stands out.9 This link presents significant differences between the sexes, mediated by hormonal factors and adaptive immunological mechanisms. These differences begin to manifest after puberty, when gonadal hormones play a predominant role in pain physiology and perception.10

Transient potential receptors are critical in pain transduction by facilitating the generation of action potentials. Channels such as TRPV1, TRPA1, TRPC1, TRPC3 TRPV2, TRPV4, TRPM3, and TRPM8 have been identified as key regulators in glial activation.11,12 These channels respond to thermal, chemical, and mechanical stimuli, and their activation triggers the release of inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and prostaglandins.9 These mediators, in turn, activate microglia and astrocytes sequentially, perpetuating central sensitization, a critical process in the allodynia and hyperalgesia characteristic of chronic pain. This phenomenon is closely related to neuroglial signaling by molecules such as glutamate and various inflammatory cytokines.12

TRPV1 is a non-selective cation channel that is activated by various stimuli such as vanilloid compounds (capsaicin and resiniferatoxin, products found in hot peppers and other plants), heat above 43° > C, protons and lipid compounds (anadamide, arachidonic acid lipoxygenase products and N-arachidonyl-dopamine), which makes it currently one of the most important members of this family of receptors in relation to pain. Other members of the TRP family are TRPV2–4, TRPM8, and TRPA1, which are activated by temperature in the noxious and non-noxious range.8,13 These channels are expressed in sensory neurons and different tissues, have distinct temperature thresholds for activation (>52 °C for TRPV2, ∼34–38 °C for TRPV3, ∼27–35 °C for TRPV4, <25–28 °C for TRPM8, and <17 °C for TRPA1) conferring them an important role in the mechanisms of thermal hyperalgesia and other pain modalities. Due to the adverse effects secondary to the use of the different analgesics available, such as NSAIDs and opioids, and the role of TRPV, TRPA and TRPM receptors in pain pathways, there is a growing interest in the development and research of molecules that, either through an agonist or antagonist effect on the receptor, broaden the range of pharmacological options for pain management.13

Hormones, neuroglia and TRP in pain perceptionHormonal modulation significantly influences TRP activation and their interaction with glia, particularly through estrogens, progesterone and testosterone.11 These hormones, derived from gonadal organization during embryonic development, play distinct roles in the regulation of these channels14:

Estrogens increase pain sensitivity by enhancing TRPV1 and TRPA1 activity. This effect is especially relevant in women in the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle. In addition, estrogenic metabolites promote glial sensitization by activating TRPA1, which could explain the higher prevalence of migraines and neuropathic pain in women.11

Progesterone acts as a negative modulator of TRPV1 and TRPA1, exerting a protective effect against neuropathic and inflammatory pain.11 This mechanism is particularly evident during pregnancy, when progesterone levels increase significantly. However, it can also aggravate allodynia by upregulating neuroregulin-1 and altering the concentrations of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10.14 In men, the absence of progesterone is associated with increased sensitivity to stimuli such as heat and irritants.14

Testosterone reduces the perception of thermal and chemical pain by activating TRPM8.11 In men, this activation attenuates sensitivity to cold pain compared to women and is significantly related to TRPA1.15

These hormonal differences, especially in women of childbearing age, generate variability in pain susceptibility depending on the phase of the menstrual cycle.14 Although TRP density in the central and peripheral nervous system is similar between sexes, studies in animal models show an overexpression of TRPV1 and TRPM8 in the spinal cord, while in the dorsal root ganglia, the concentrations are equivalent.16

Additionally, other factors contribute to the TRP-glia interaction and to sex differences in pain:

Immunological factors: Women present a more intense inflammatory response, characterized by a greater release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-17, mediated by TRPV1-microglia-macrophage interaction. This exacerbates peripheral and central sensitization.17

Genetic factors: Polymorphisms in genes encoding TRPV3 and TRPA1 have been linked to a greater predisposition to chronic pain in women.17

Environmental factors: Positive regulation of TRP, especially against mechanical pain and cold, is predominantly observed in women due to low testosterone concentration.15,16

These sex differences have clinical implications in conditions such as migraine, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), and inflammatory pain. For example, in migraine, temperature-sensitive TRPA1, TRPV1 and TRPM8 channels, expressed in afferent neurons of the trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia, show increased activation during the menstrual phase, whereas their incidence decreases during pregnancy. TRPV4 and TRPV2 have also been linked, although their role is not fully elucidated.11 In CIPN, women experience a higher incidence and severity of symptoms, attributed to the estrogen-modulated interaction of TRPV1 with the IL-23/IL-17α inflammatory axis in the central nervous system. In postmenopausal women, the clinical presentation of CIPN is less frequent.11

Understanding how sex hormones and other factors modulate the TRP-glia interaction is fundamental to develop differentiated therapeutic strategies for the management of chronic pain, considering the differences in hormonal and therefore neurophysiological characteristics of each sex.

Pharmacological developments in TRP and neuroglia for the treatment of painCapsaicin, present in hot peppers and currently used transdermally in neuropathic pain, provokes a strong increase of signals in cells expressing TRPV1 with a remarkable agonist activity on cells expressing this receptor.18 A potent analog of capsaicin with analgesic value is Resiniferatoxin, which, in animal studies, has been shown to have a dose-dependent effect of reversible and non-reversible desensitization, the latter due to secondary neuropathy and is under development for use in humans. There are also molecules that act on the TRPV3 receptor, such as the TRPV3 antagonist of tetrahydroquinoline amide, with good selectivity against other TRP thermoreceptors. These molecules have shown good efficacy in the inflammatory pain model.9

It has been shown that modulation of TRPV1 and TRPA1 receptors can control several preclinical models of pain and dual inhibition of these receptors has been proposed as a viable therapeutic target.19 Numerous compounds antagonistic to these receptors exist as potential drugs for clinical use, one such compound is 3-(4,5-diphenyl-1,3-oxazol-2-yl) propanal oxime (SZV-1287) which has been shown to inhibit TRPA1 and TRV1 receptor-mediated Ca2+ entry in cultured trigeminal ganglion neurons, as well as decreasing TRPA1-mediated calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) release in nerve terminals of peripheral nerves, also inhibits AITC (Allyl isothiocyanate)- and capsaicin-induced Ca2+ entry in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells expressing cloned TRPA1 and TRPV1 receptors, these findings place SZV-1287 as a candidate for the development of drugs for neuropathic, arthritis and/or migraine pain.20 Administration of SZV-1287 resulted in a significant reduction of approximately 50% of neuropathic hyperalgesia after nerve ligation, which was not observed in TRPA1- or TRPV1-deficient mice.21

Another molecule that has demonstrated TRPV1 and TRPA1 receptor antagonist activity is liquiritin, a flavonoid ingredient of licorice, said compound can dually inhibit the response of these receptors to the stimulus with capsaicin and AITC, and it also decreases inflammation and activation of the NF-κB pathway.22

Through the pharmacophore fusion strategy, the synthesis of ligands has been achieved in which the phenylpiperidine group or the N-phenyl-N-(piperidin-4-yl)propionamide group as MOR pharmacophore was fused with the benzylpiperazinyl urea-based TRPV1, said molecule named Compound 5a demonstrated in vitro antagonist activity against the μ opioid receptors (MOR) and the TRPV1 receptor, which in turn resulted in a dose-dependent analgesic action without the adverse effects commonly associated with TRPV1 antagonists (analgesic tolerance, hyperthermia), with acceptable pharmacokinetic properties and the ability to permeate the blood–brain barrier.23

Furthermore, the dopamine amides of mefenamic acid have agonist activity on the TRPV1 receptor, while the arachidonyl amide of a metabolite of dipyrone has TRPV1 antagonist activity. Flufenamic acid dopamide has TRPV1 agonist action and in turn exhibits inhibitory activity on cyclooxygenase (COX) so it may act on two important mechanisms of pain and inflammation. These findings suggest that some synthetic amides, in addition to their anti-inflammatory activity, are capable of interacting, either as agonists or antagonists, on the TRPV1 receptor, which may contribute significantly to their analgesic effect.24

Although many of these interventions are theoretical or in the developmental stages, the implementation of drugs such as capsaicin has shown us the great potential of these receptors in neuropathic pain, where the modification of neuroglia expression plays a fundamental role.

ConclusionNeuroglia has a fundamental role in pain perception, where transient potential receptors mediate different pathophysiological processes that may vary in relation to our hormonal and genetic profile. The understanding of these cells and their receptors is increasingly important in the advent of new therapeutic alternatives.

Ethical considerationsA study involving patients or their clinical information was not performed.

FundingThe authors did not receive funding to carry out this study.

We declare no conflict of interest.