The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) is frequently used in clinical practice to evaluate cognitive function. It is quick to administer (20-30minutes) and is not influenced by a learning effect. The RBANS includes 4 parallel versions and has a high discriminative ability.

Our study provides normative data from the RBANS-E (Spanish-language version of RBANS form A) for a Spanish population aged 20-89 years.

MethodsThe study included 609 subjects aged 20-89 years. Participants were evaluated at baseline with a short interview, a cognitive screening test (Mini–Mental State Examination), and a functional scale (Rapid Disability Rating Scale). The RBANS-E was then administered to all 609 participants.

ResultsOur results show the influence of education on all subtest scores. Sex was observed to have no impact on any subtest.

ConclusionOur study provides highly useful normative data for the cognitive evaluation of young and adult populations.

Repeatable Battery for the Asessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) es utilizada habitualmente en la práctica clínica para la evaluación de funciones cognitivas. Se caracteriza por su corta duración, 20-30minutos de administración, por la ausencia de efecto aprendizaje, dispone de 4 versiones paralelas y por su capacidad discriminativa de diferentes enfermedades.

Se presentan datos normativos de la RBANS-E (versión española forma A de la batería) para población española de 20-89 años.

MétodosSeiscientos nueve individuos accedieron a participar. Se les sometió a una valoración previa mediante anamnesis que incluía el Mini Mental State Examination como instrumento de cribado cognitivo y la Blessed Disability Rating Scale como escala funcional. A los 609 sujetos sanos de entre 20 y 89 años de edad se les administró la batería RBANS-E en una sola sesión.

ResultadosLos resultados muestran la influencia de la escolaridad en las puntuaciones de todos los subtest. No se observa influencia del género en ninguno de ellos.

ConclusionesLas normas obtenidas aportan datos de gran utilidad clínica para la evaluación cognitiva de población joven y adulta.

Neuropsychological evaluation is a complex task requiring different assessment methods adapted to the disease under study, to the evaluator's objectives, and to the patient's status. The length and thoroughness of a neuropsychological evaluation of cognitive function depends on the complexity of the studies and instruments used; ideographic studies, complex or simple test batteries, functional scales, and brief scales1 are the most frequent tools. The evaluator must also be familiar with the principles of neuropsychometric assessment and be able to apply them to the use of tools validated and normalised for the population under study. This task requires a multidimensional approach and is much more complex than simply administering a test.

The most frequently recommended method for neuropsychometric assessment of dementia is the use of a multidimensional test battery with psychometric properties including sensitive tests for each cognitive area.2 The assessment tools used in Spain include the Barcelona Test (Programa Integrado de Exploración Neuropsicológica-Test Barcelona), in both the originall,2 and short forms,3 and such other short test batteries as the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS),4 the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale,5 and the Cambridge Cognitive Examination, included in the Cambridge Mental Disorders of the Elderly Examination,6 for the evaluation of cognitive impairment in different populations; and others specifically designed for evaluating people with dementia, such as the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale7 and the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease.8

The RBANS has several advantages over the other batteries. It is a multidimensional method and includes 4 alternative forms (forms A, B, C, and D) in order to avoid the learning effect in repeated evaluations. It is easy to administer; administration time ranges from 20 to 30minutes, and it is administered on a one-on-one basis.9 The RBANS has been translated into several languages and validated for different countries and continents, including Australia,10 Russia,11 Asia,12–14 Turkey,15 and Spain.16,17 A study providing normative data for the Spanish-language version of the RBANS (RBANS-E) has recently been published.16 The study presents normative data for patients aged 20-89 years, classified into 6 age groups (10-year age ranges, except for the 20-39 age group). However, normative data for individuals older than 60 years are based on small samples (ranging from 40 to 44 individuals). The purpose of this study was to provide new normative data for a larger number of age groups (3-year age ranges). To optimise the normative sample for each age group, we followed the methodology used in the NEURONORMA project.18

MethodsParticipantsA consecutive sample was recruited from among the companions of patients referred to the dementia diagnosis and treatment unit at Hospital Universitari Mútua in Terrassa by other care centres and volunteer associations serving the general population.

Participation was voluntary and unpaid; all participants met the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria: (1) living in Spain; (2) accepting the terms of participation by verbally providing informed consent; (3) age between 20 and 89 years; (4) having basic reading and writing skills; (5) having sufficient hearing, sight, and physical condition to complete the test; (6) scoring ≥24 on the MMSE19; and (7) having a good functional status according to the Blessed Dementia Rating Scale.20

Exclusion criteria: (1) any type of CNS disorder affecting cognition and/or functional abilities; (2) history of CNS infection (meningitis, encephalitis, etc.); (3) history of severe psychiatric illness according to DSM-IV criteria; (4) untreated, clinically significant hypothyroidism; (5) known metabolic disorders; (6) history of alcohol or other drug abuse in the preceding 24 months, and (7) presence of any factor rendering the individual's participation inappropriate according to the judgement of the lead researcher.

InstrumentWe used the Spanish-language version of the RBANS, published in 2012.17 As with the original version, the RBANS-E is designed for use with adults aged 20-89 years and comprises 12 tests that provide a total score as well as scores for 5 different cognitive domains: attention (“digit span” and “coding”), language (“picture naming” and “semantic fluency”), visuospatial/constructional skills (“figure copy” and “line orientation”), immediate memory (“list learning” and “story memory”), and delayed memory (“list recall,” “list recognition,” “story recall,” and “figure recall”). During the process of adaptation, the tests with verbal content were translated following the forward-translation/back-translation method,21–23 and subsequently adapted according to the criteria of imaginability and frequency of use of words.24 Reliability and validity results were published by Muntal Encinas et al.17

ProcedureWe took all participants’ medical histories and administered the MMSE and the Blessed Dementia Rating Scale. Participants meeting all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were administered the RBANS-E battery19 in a single session, individually, by a team of neuropsychologists trained to administer the test battery.

Statistical analysisNorms were established following the methodology of the NEURONORMA project for normative data,18 based on the following strategy:

Identifying sociodemographic variables to be consideredWe evaluated the correlation between sociodemographic variables (age, sex, and years of schooling) and raw RBANS subtest scores. Sociodemographic variables sharing at least 5% of the variance with raw scores (coefficient of determination R2≥0.05) were deemed relevant for the interpretation of scores.

Maximising the number of participantsAge-adjusted norms were created when age was found to be relevant for the interpretation of scores. In our sample, we established 20 age groups, with the following minimum and maximum ages: 20-24, 25-27, 28-30, 31-33, 34-36, 37-39, 40-42, 43-45, 46-48, 49-51, 52-54, 55-57, 58-60, 61-63, 64-66, 67-69, 70-72, 73-75, 76-78, and 79-89. With the exception of the first and the last groups, all age groups cover a range of 3 years.

Following the strategy proposed by Pauker,25 we used overlapping age bands to maximise the usefulness of norm data. Starting at the age of 20, we defined 10-year age ranges; however, the youngest and oldest groups covered ranges of 9 and 14 years, respectively. The minimum and maximum age values for each of the categories established for the analysis were as follows: 20-28, 21-31, 24-34, 27-37, 30-40, 33-43, 36-46, 39-49, 42-52, 45-55, 48-58, 51-61, 54-64, 57-67, 60-70, 63-73, 66-76, 69-79, 72-82, and 75-89. With the exception of the youngest and the oldest groups, the mean values of these age categories coincide with the mean values of the age groups considered for the norms.

Calculating normative scaled scoresRaw scores were normalised by transforming them into scaled scores following the methodology proposed by Ivnik et al.26 Raw scores were converted to percentile ranks. Percentile ranks were calculated according to the procedure described by Crawford et al.,27 with the assumption that scores are continuous. Linear transformation was subsequently performed to transform percentile ranks into scaled scores, with a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 3.

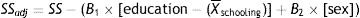

Adjusting scaled scores for sex and years of schoolingScaled scores were adjusted with linear regression models according to the procedure described by Peña-Casanova et al.18 When the variables years of schooling or sex were found to be relevant for the interpretation of scores, linear regression was performed using the sociodemographic variable as the explanatory variable and the scaled score as the explained variable. Thus, adjusted scaled scores were calculated as follows:

where B is the unstandardised regression coefficient.According to the procedure described by Mungas et al.,28 the analysis considered the difference between years of schooling (education) and a reference value. Following the procedure used by Peña-Casanova et al.,18 we used the mean years of schooling of the norm sample (11 years in our case). The resulting values were truncated to the lower whole number.

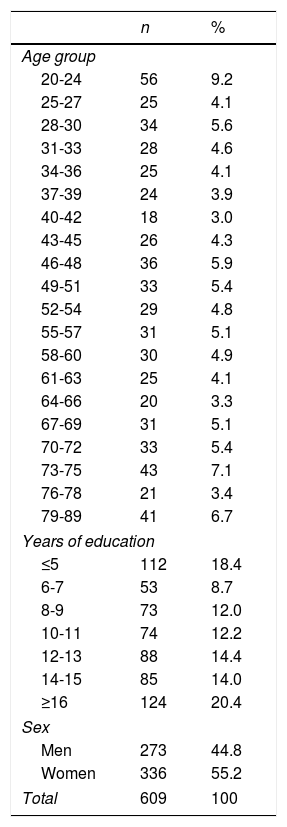

ResultsApplication of the inclusion and exclusion criteria left a sample of 609 healthy individuals aged 20-89 years: 273 men (mean age [SD], 52.42 [19.49]; mean years of schooling [SD], 11.38 [5.63]) and 336 women (mean age, 50.51 [18.17]; mean years of schooling, 10.66 [5.40]). Right-handed individuals accounted for 96.7% of the sample; 2.1% were ambidextrous and 1.1% were left-handed. Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of our sample.

Demographic characteristics of the sample.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 20-24 | 56 | 9.2 |

| 25-27 | 25 | 4.1 |

| 28-30 | 34 | 5.6 |

| 31-33 | 28 | 4.6 |

| 34-36 | 25 | 4.1 |

| 37-39 | 24 | 3.9 |

| 40-42 | 18 | 3.0 |

| 43-45 | 26 | 4.3 |

| 46-48 | 36 | 5.9 |

| 49-51 | 33 | 5.4 |

| 52-54 | 29 | 4.8 |

| 55-57 | 31 | 5.1 |

| 58-60 | 30 | 4.9 |

| 61-63 | 25 | 4.1 |

| 64-66 | 20 | 3.3 |

| 67-69 | 31 | 5.1 |

| 70-72 | 33 | 5.4 |

| 73-75 | 43 | 7.1 |

| 76-78 | 21 | 3.4 |

| 79-89 | 41 | 6.7 |

| Years of education | ||

| ≤5 | 112 | 18.4 |

| 6-7 | 53 | 8.7 |

| 8-9 | 73 | 12.0 |

| 10-11 | 74 | 12.2 |

| 12-13 | 88 | 14.4 |

| 14-15 | 85 | 14.0 |

| ≥16 | 124 | 20.4 |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 273 | 44.8 |

| Women | 336 | 55.2 |

| Total | 609 | 100 |

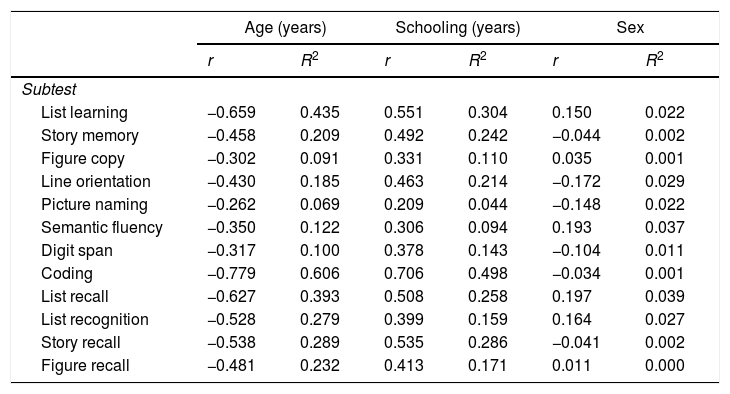

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients and the coefficients of determination for the different RBANS subtests and the sociodemographic variables age, sex, and years of schooling. All scores analysed shared over 5% of the variance with age, indicating the need for a different norm for each age group. Norms were corrected for years of schooling, as this variable also shared over 5% of the variance with all RBANS subtest scores, except for the “picture naming” subscale. Adjustment for sex was not necessary (Table 2).

Correlation coefficients (r) and coefficients of determination (R2) between RBANS subtest raw scores and age, schooling, and sex.

| Age (years) | Schooling (years) | Sex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | R2 | r | R2 | r | R2 | |

| Subtest | ||||||

| List learning | −0.659 | 0.435 | 0.551 | 0.304 | 0.150 | 0.022 |

| Story memory | −0.458 | 0.209 | 0.492 | 0.242 | −0.044 | 0.002 |

| Figure copy | −0.302 | 0.091 | 0.331 | 0.110 | 0.035 | 0.001 |

| Line orientation | −0.430 | 0.185 | 0.463 | 0.214 | −0.172 | 0.029 |

| Picture naming | −0.262 | 0.069 | 0.209 | 0.044 | −0.148 | 0.022 |

| Semantic fluency | −0.350 | 0.122 | 0.306 | 0.094 | 0.193 | 0.037 |

| Digit span | −0.317 | 0.100 | 0.378 | 0.143 | −0.104 | 0.011 |

| Coding | −0.779 | 0.606 | 0.706 | 0.498 | −0.034 | 0.001 |

| List recall | −0.627 | 0.393 | 0.508 | 0.258 | 0.197 | 0.039 |

| List recognition | −0.528 | 0.279 | 0.399 | 0.159 | 0.164 | 0.027 |

| Story recall | −0.538 | 0.289 | 0.535 | 0.286 | −0.041 | 0.002 |

| Figure recall | −0.481 | 0.232 | 0.413 | 0.171 | 0.011 | 0.000 |

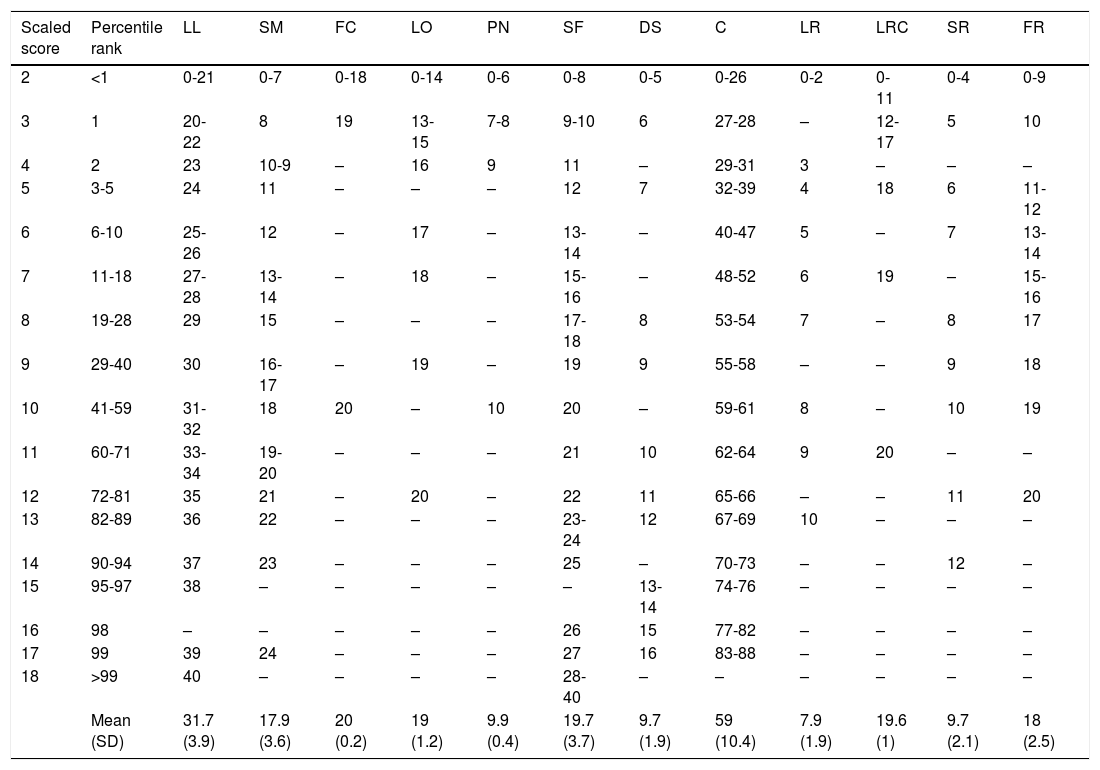

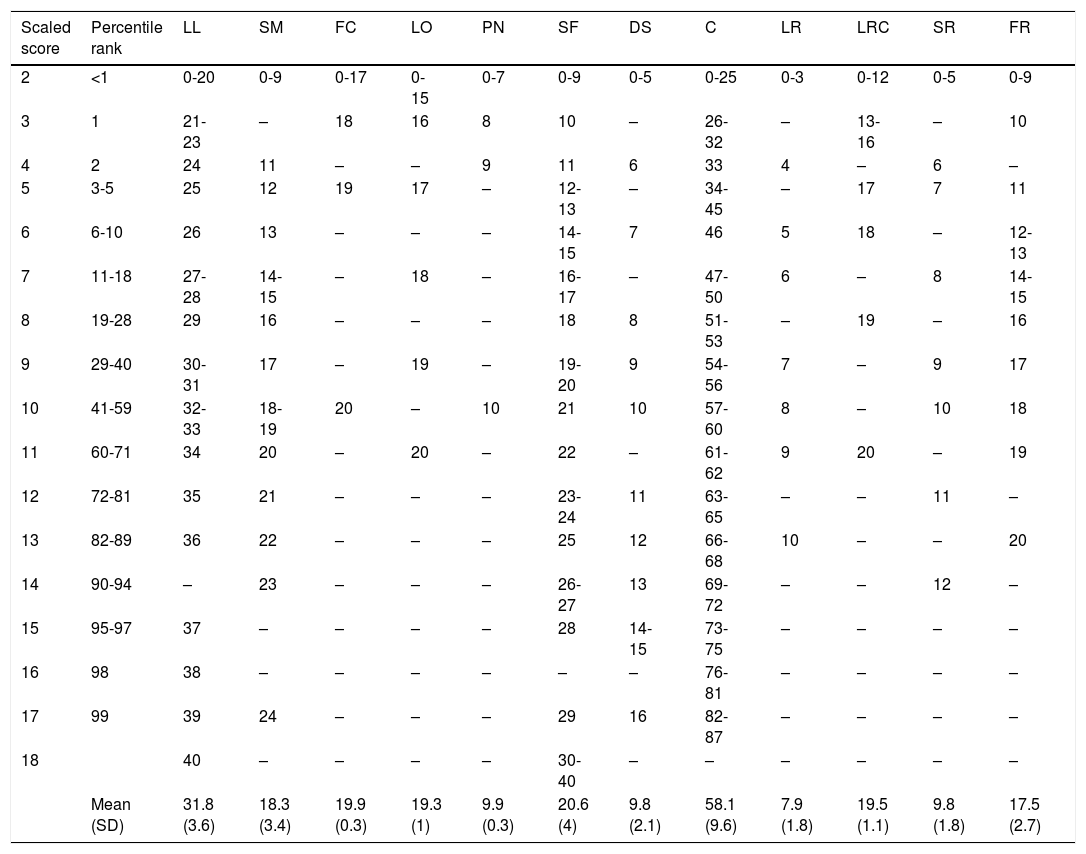

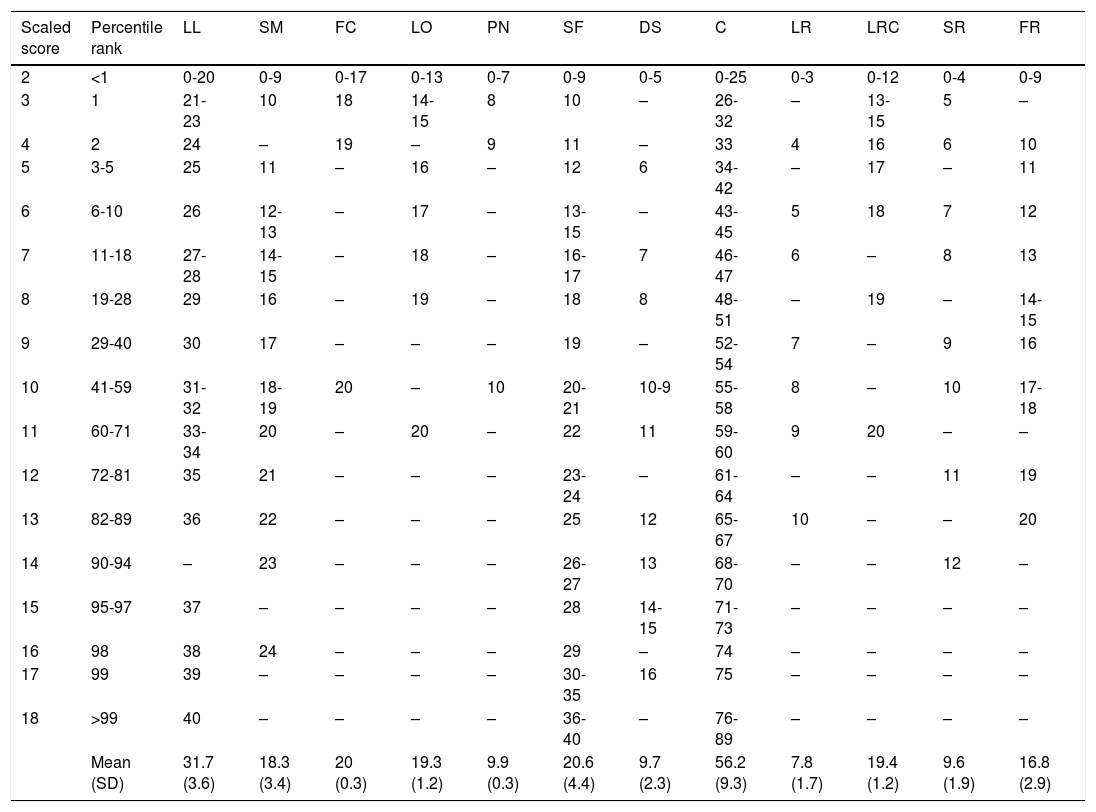

Norms for some of the 20 age groups are shown in Tables 3–5.

Scaled scores adjusted for ages 20-24 (age band for establishing norms, 20-28; sample size, 86).

| Scaled score | Percentile rank | LL | SM | FC | LO | PN | SF | DS | C | LR | LRC | SR | FR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | <1 | 0-21 | 0-7 | 0-18 | 0-14 | 0-6 | 0-8 | 0-5 | 0-26 | 0-2 | 0-11 | 0-4 | 0-9 |

| 3 | 1 | 20-22 | 8 | 19 | 13-15 | 7-8 | 9-10 | 6 | 27-28 | – | 12-17 | 5 | 10 |

| 4 | 2 | 23 | 10-9 | – | 16 | 9 | 11 | – | 29-31 | 3 | – | – | – |

| 5 | 3-5 | 24 | 11 | – | – | – | 12 | 7 | 32-39 | 4 | 18 | 6 | 11-12 |

| 6 | 6-10 | 25-26 | 12 | – | 17 | – | 13-14 | – | 40-47 | 5 | – | 7 | 13-14 |

| 7 | 11-18 | 27-28 | 13-14 | – | 18 | – | 15-16 | – | 48-52 | 6 | 19 | – | 15-16 |

| 8 | 19-28 | 29 | 15 | – | – | – | 17-18 | 8 | 53-54 | 7 | – | 8 | 17 |

| 9 | 29-40 | 30 | 16-17 | – | 19 | – | 19 | 9 | 55-58 | – | – | 9 | 18 |

| 10 | 41-59 | 31-32 | 18 | 20 | – | 10 | 20 | – | 59-61 | 8 | – | 10 | 19 |

| 11 | 60-71 | 33-34 | 19-20 | – | – | – | 21 | 10 | 62-64 | 9 | 20 | – | – |

| 12 | 72-81 | 35 | 21 | – | 20 | – | 22 | 11 | 65-66 | – | – | 11 | 20 |

| 13 | 82-89 | 36 | 22 | – | – | – | 23-24 | 12 | 67-69 | 10 | – | – | – |

| 14 | 90-94 | 37 | 23 | – | – | – | 25 | – | 70-73 | – | – | 12 | – |

| 15 | 95-97 | 38 | – | – | – | – | – | 13-14 | 74-76 | – | – | – | – |

| 16 | 98 | – | – | – | – | – | 26 | 15 | 77-82 | – | – | – | – |

| 17 | 99 | 39 | 24 | – | – | – | 27 | 16 | 83-88 | – | – | – | – |

| 18 | >99 | 40 | – | – | – | – | 28-40 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mean (SD) | 31.7 (3.9) | 17.9 (3.6) | 20 (0.2) | 19 (1.2) | 9.9 (0.4) | 19.7 (3.7) | 9.7 (1.9) | 59 (10.4) | 7.9 (1.9) | 19.6 (1) | 9.7 (2.1) | 18 (2.5) |

C: coding; DS: digit span; FC: figure copy; FR: figure recall; LL: list learning; LO: line orientation; LR: list recall; LRC: list recognition; PN: picture naming; SF: semantic fluency; SM: story memory; SR: story recall.

Scaled scores adjusted for ages 25-27 (age band for establishing norms, 21-31; sample size, 107).

| Scaled score | Percentile rank | LL | SM | FC | LO | PN | SF | DS | C | LR | LRC | SR | FR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | <1 | 0-20 | 0-9 | 0-17 | 0-15 | 0-7 | 0-9 | 0-5 | 0-25 | 0-3 | 0-12 | 0-5 | 0-9 |

| 3 | 1 | 21-23 | – | 18 | 16 | 8 | 10 | – | 26-32 | – | 13-16 | – | 10 |

| 4 | 2 | 24 | 11 | – | – | 9 | 11 | 6 | 33 | 4 | – | 6 | – |

| 5 | 3-5 | 25 | 12 | 19 | 17 | – | 12-13 | – | 34-45 | – | 17 | 7 | 11 |

| 6 | 6-10 | 26 | 13 | – | – | – | 14-15 | 7 | 46 | 5 | 18 | – | 12-13 |

| 7 | 11-18 | 27-28 | 14-15 | – | 18 | – | 16-17 | – | 47-50 | 6 | – | 8 | 14-15 |

| 8 | 19-28 | 29 | 16 | – | – | – | 18 | 8 | 51-53 | – | 19 | – | 16 |

| 9 | 29-40 | 30-31 | 17 | – | 19 | – | 19-20 | 9 | 54-56 | 7 | – | 9 | 17 |

| 10 | 41-59 | 32-33 | 18-19 | 20 | – | 10 | 21 | 10 | 57-60 | 8 | – | 10 | 18 |

| 11 | 60-71 | 34 | 20 | – | 20 | – | 22 | – | 61-62 | 9 | 20 | – | 19 |

| 12 | 72-81 | 35 | 21 | – | – | – | 23-24 | 11 | 63-65 | – | – | 11 | – |

| 13 | 82-89 | 36 | 22 | – | – | – | 25 | 12 | 66-68 | 10 | – | – | 20 |

| 14 | 90-94 | – | 23 | – | – | – | 26-27 | 13 | 69-72 | – | – | 12 | – |

| 15 | 95-97 | 37 | – | – | – | – | 28 | 14-15 | 73-75 | – | – | – | – |

| 16 | 98 | 38 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 76-81 | – | – | – | – |

| 17 | 99 | 39 | 24 | – | – | – | 29 | 16 | 82-87 | – | – | – | – |

| 18 | 40 | – | – | – | – | 30-40 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Mean (SD) | 31.8 (3.6) | 18.3 (3.4) | 19.9 (0.3) | 19.3 (1) | 9.9 (0.3) | 20.6 (4) | 9.8 (2.1) | 58.1 (9.6) | 7.9 (1.8) | 19.5 (1.1) | 9.8 (1.8) | 17.5 (2.7) |

C: coding; DS: digit span; FC: figure copy; FR: figure recall; LL: list learning; LO: line orientation; LR: list recall; LRC: list recognition; PN: picture naming; SF: semantic fluency; SM: story memory; SR: story recall.

Scaled scores adjusted for ages 28-30 (age band for establishing norms, 24-34; sample size, 105).

| Scaled score | Percentile rank | LL | SM | FC | LO | PN | SF | DS | C | LR | LRC | SR | FR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | <1 | 0-20 | 0-9 | 0-17 | 0-13 | 0-7 | 0-9 | 0-5 | 0-25 | 0-3 | 0-12 | 0-4 | 0-9 |

| 3 | 1 | 21-23 | 10 | 18 | 14-15 | 8 | 10 | – | 26-32 | – | 13-15 | 5 | – |

| 4 | 2 | 24 | – | 19 | – | 9 | 11 | – | 33 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 10 |

| 5 | 3-5 | 25 | 11 | – | 16 | – | 12 | 6 | 34-42 | – | 17 | – | 11 |

| 6 | 6-10 | 26 | 12-13 | – | 17 | – | 13-15 | – | 43-45 | 5 | 18 | 7 | 12 |

| 7 | 11-18 | 27-28 | 14-15 | – | 18 | – | 16-17 | 7 | 46-47 | 6 | – | 8 | 13 |

| 8 | 19-28 | 29 | 16 | – | 19 | – | 18 | 8 | 48-51 | – | 19 | – | 14-15 |

| 9 | 29-40 | 30 | 17 | – | – | – | 19 | – | 52-54 | 7 | – | 9 | 16 |

| 10 | 41-59 | 31-32 | 18-19 | 20 | – | 10 | 20-21 | 10-9 | 55-58 | 8 | – | 10 | 17-18 |

| 11 | 60-71 | 33-34 | 20 | – | 20 | – | 22 | 11 | 59-60 | 9 | 20 | – | – |

| 12 | 72-81 | 35 | 21 | – | – | – | 23-24 | – | 61-64 | – | – | 11 | 19 |

| 13 | 82-89 | 36 | 22 | – | – | – | 25 | 12 | 65-67 | 10 | – | – | 20 |

| 14 | 90-94 | – | 23 | – | – | – | 26-27 | 13 | 68-70 | – | – | 12 | – |

| 15 | 95-97 | 37 | – | – | – | – | 28 | 14-15 | 71-73 | – | – | – | – |

| 16 | 98 | 38 | 24 | – | – | – | 29 | – | 74 | – | – | – | – |

| 17 | 99 | 39 | – | – | – | – | 30-35 | 16 | 75 | – | – | – | – |

| 18 | >99 | 40 | – | – | – | – | 36-40 | – | 76-89 | – | – | – | – |

| Mean (SD) | 31.7 (3.6) | 18.3 (3.4) | 20 (0.3) | 19.3 (1.2) | 9.9 (0.3) | 20.6 (4.4) | 9.7 (2.3) | 56.2 (9.3) | 7.8 (1.7) | 19.4 (1.2) | 9.6 (1.9) | 16.8 (2.9) |

C: coding; DS: digit span; FC: figure copy; FR: figure recall; LL: list learning; LO: line orientation; LR: list recall; LRC: list recognition; PN: picture naming; SF: semantic fluency; SM: story memory; SR: story recall.

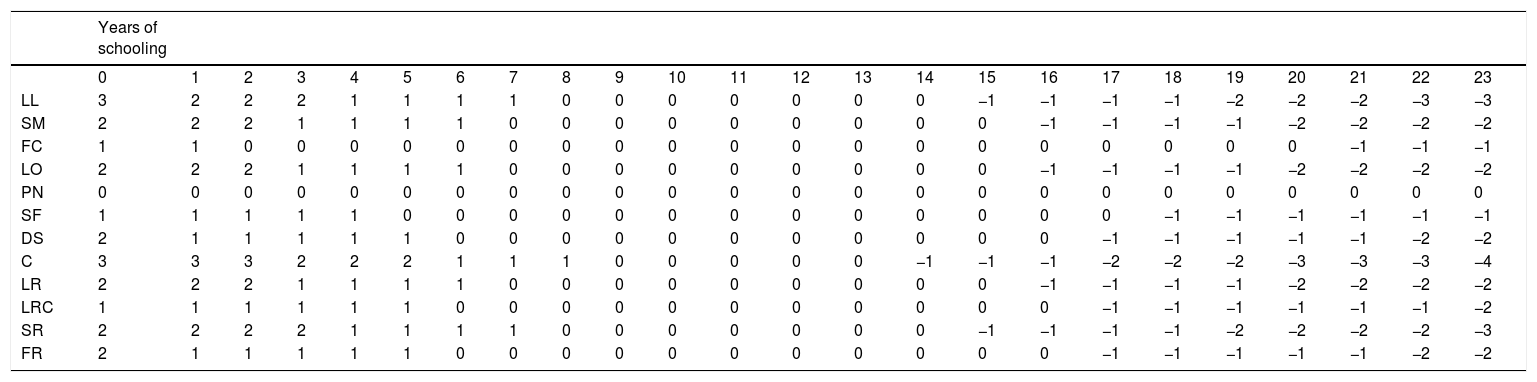

Table 6 shows the corrections to be applied to RBANS scaled scores according to years of schooling. The values obtained in Table 6 must be added to the scaled values obtained in Tables 3–5. Let us assume, for example, that a person obtains a raw score corresponding to a scaled score of 5 for the “list learning” subscale. If that person had 5 years of schooling, the corrected scaled score would be 5+1=6. If the education level were 17 years of schooling, the corrected scaled score would be 5−1=4. Note that scaled values in the “picture naming” subtest are not corrected for years of schooling.

Scaled scores for the RBANS subtests corrected for years of schooling.

| Years of schooling | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | |

| LL | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −3 | −3 |

| SM | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 |

| FC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| LO | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 |

| PN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SF | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| DS | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −2 | −2 |

| C | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −3 | −3 | −3 | −4 |

| LR | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 |

| LRC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −2 |

| SR | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −3 |

| FR | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −2 | −2 |

C: coding; DS: digit span; FC: figure copy; FR: figure recall; LL: list learning; LO: line orientation; LR: list recall; LRC: list recognition; PN: picture naming; SF: semantic fluency; SM: story memory; SR: story recall.

The coefficient regression values used for correction were as follows: LL: 0.277; SM: 0.244; FC: 0.103; LO: 0.246; SF: 0.152; DS: 0.197; C: 0.350; LR: 0.245; LRC: 0.169; SR: 0.264; FR: 0.199.

Regarding sociodemographic variables, age and education level had a statistically significant influence in all subtests; this was not true for patients with 9-13 years of schooling, however. Furthermore, in patients with 8 and 14 years of schooling, education level only influenced “coding” subscale scores.

DiscussionThis study provides new normative data for Spanish individuals aged 20-89 years. Our sample was selected using strict inclusion and exclusion criteria.

One of the limitations of our study is the selection of healthy participants. Firstly, given that some participants were related to patients with dementia, we may hypothesise that a genetic component may act as an uncontrolled bias, although we cannot be certain that the relatives had begun or were going to develop the disease, nor that they had cognitive alterations typical of the disease that may affect test performance.

Furthermore, the MMSE cut-off point used as an inclusion criterion (≥24, widely recognised as a highly sensitive cut-off point for differentiating between dementia and normal cognitive function19 and also used as an inclusion criterion in other Spanish normative studies29) may not be the most appropriate tool since it may not be sufficiently sensitive in differentiating between mild cognitive impairment and normal cognitive function. This underlines the importance of the remaining inclusion and exclusion criteria. The purpose of the selection criteria was to gather a sample with scores lying around the middle of the normal distribution (rather than at the extremes), which would ensure greater adaptation of the norms to the general population.

According to an observational analysis of the norms obtained for each subtest, some scores that would indicate cognitive impairment in other neuropsychological tests indicated normal cognitive function in our test. This was the case with the norms for the “list recall” subtest for ages over 70 years. For instance, a score of 0 on this subscale (inability to recall any word from the list) is normal for that age group in the RBANS-E but would be considered pathological in other memory tests, such as the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test.29

This may be due to a sample bias for this subtest and age group, the small sample size, or this subscale's low sensitivity for detecting cognitive impairment in prodromal stages of the disease in patients aged over 70 years; future studies should include more patients in this age band.

Another relevant finding of our study, again related to the role of sociodemographic variables, revolves around establishing norms, and more specifically around the distribution of scores for each norm. The socioeconomic context of the study and our sample's characteristics may be responsible for the fact that some cells are underrepresented. As a result, scaled scores may vary depending on the test and the person's age, with many scores not being matched with raw scores.

These peculiarities and limitations require us to exercise caution in interpreting the findings for some age bands.

Cognitive assessment tools should be adapted to the reference population, normalised, and have good psychometric properties; new normative data from different versions of the RBANS would be extremely valuable. The validated normative RBANS-E scores presented here are intended to assist in the detection and diagnosis of cognitive impairment. Poor test performance alone does not indicate dementia; thorough examination should be performed to assess all the variables that define an individual's clinical profile.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Muntal S, Doval E, Badenes D, Casas-Hernanz L, Cerulla N, Calzado N, et al. Nuevos datos normativos de la versión española de la Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) forma A. Neurología. 2020;35:303–310.