This study aimed to assess the safety and effectiveness of peripheral neurostimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) in the treatment of refractory chronic cluster headache.

DevelopmentVarious medical databases were used to perform a systematic review of the scientific literature. The search for articles continued until 31 October 2016, and included clinical trials, systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses, health technology assessment reports, and clinical practice guidelines that included measurements of efficiency/effectiveness or adverse effects associated with the treatment. The review excluded cohort studies, case–control studies, case series, literature reviews, letters to the editor, opinion pieces, editorials, and studies that had been duplicated or outdated by later publications from the same institution. Regarding effectiveness, we found that SPG stimulation had positive results for pain relief, attack frequency, medication use, and patients’ quality of life. In the results regarding safety, we found a significant number of adverse events in the first 30 days following the intervention. Removal of the device was necessary in some patients. Little follow-up data, and no long-term data, is available.

ConclusionsThese results are promising, despite the limited evidence available. We consider it essential for research to continue into the safety and efficacy of SPG stimulation for patients with refractory chronic cluster headache. In cases where this intervention may be indicated, treatment should be closely monitored.

El objetivo es evaluar la eficacia y seguridad de los neuroestimuladores periféricos del ganglio esfenopalatino (GEP) para el tratamiento de la cefalea en racimos crónica refractaria al tratamiento.

DesarrolloRevisión sistemática de la literatura científica. Se identificaron estudios mediante una búsqueda en diferentes bases de datos. Las estrategias de búsqueda se realizaron hasta el 31 de octubre de 2016, incluyendo ensayos clínicos, revisiones sistemáticas o metaanálisis, informes de evaluación de tecnologías sanitarias y guías de práctica clínica que recogieran medidas de eficacia/efectividad o efectos adversos asociados al tratamiento. Se excluyeron estudios de cohortes, casos y controles, series de casos, revisiones narrativas, cartas al director, artículos de opinión, editoriales y estudios duplicados o desfasados por estudios posteriores de la misma institución. Respecto a la eficacia, los resultados son positivos tras la estimulación del GEP en relación con el alivio de dolor, el número de episodios, el uso de la medicación o la calidad de vida del paciente. En relación con la seguridad, hay un número importante de efectos adversos en los primeros 30 días de la intervención y en algunos pacientes fue necesaria la retirada del dispositivo. Los datos de seguimiento son a corto plazo y escasos.

ConclusionesLos resultados resultan prometedores a pesar de que la evidencia disponible es limitada. Consideramos fundamental continuar con la investigación sobre la seguridad y eficacia de los neuroestimuladores del GEP en la cefalea en racimos crónica. En aquellos casos en que pueda estar indicada la intervención, el tratamiento debería realizarse supervisado en un estudio de monitorización.

Cluster headache (CH) is a primary headache of the group of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. It is characterised by episodes of severe, unilateral periocular pain combined with ipsilateral vegetative symptoms, including ptosis, myosis, sweating, tearing, rhinorrhoea, palpebral oedema, and restlessness or agitation. CH can be diagnosed in the absence of ipsilateral vegetative symptoms provided that the patient presents restlessness or agitation. Attacks may last 15-180minutes and present 2-8 times per day, predominantly during the night. CH may be episodic, with attacks alternating with pain-free periods lasting months to years; or chronic, with attacks occurring for one year or longer without remission, or with remission periods lasting less than a month.1

According to the literature, the incidence of CH ranges from 2.5 to 9.8 cases per 100000 person-years; prevalence ranges from 53 to 381 cases per 100000 population. CH seems to be more frequent in men, with male-to-female ratios ranging from 7:1 to 3:1.2–7

Treatment focuses on eliminating the trigger factors of headache attacks, when applicable. Pharmacological treatment includes symptomatic medications, aimed at controlling acute episodes (sumatriptan is the drug of choice), and prophylactic medications. The prophylactic approach includes transitional treatment (with drugs intended to interrupt the active episode, such as steroids, or with occipital nerve block) and preventive maintenance treatment (with drugs consolidating remission and preventing early relapses; e.g., verapamil). Preventive treatment should be administered during the attack and progressively withdrawn after a month without episodes.2,8,9

Refractory patients may benefit from trigeminal nerve section surgery, which is associated with more adverse reactions and complications. Other alternatives, such as sphenopalatine ganglion neurostimulation, have recently been developed. The sphenopalatine ganglion is an ovoid collection of parasympathetic cells with no sensory function. It has multiple connections with facial and trigeminal nerve branches and is thought to be involved in the pathogenesis and maintenance of atypical facial pain and unilateral headache; this supports its role as a potential therapeutic target. Sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation may be performed with a microstimulator, which is implanted with a minimally invasive procedure. The microstimulator is powered by a remote controller, which patients use as required; physicians can adjust parameters based on each patient's needs.8,9

This study evaluates the safety and efficacy of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation for the treatment of refractory chronic CH.

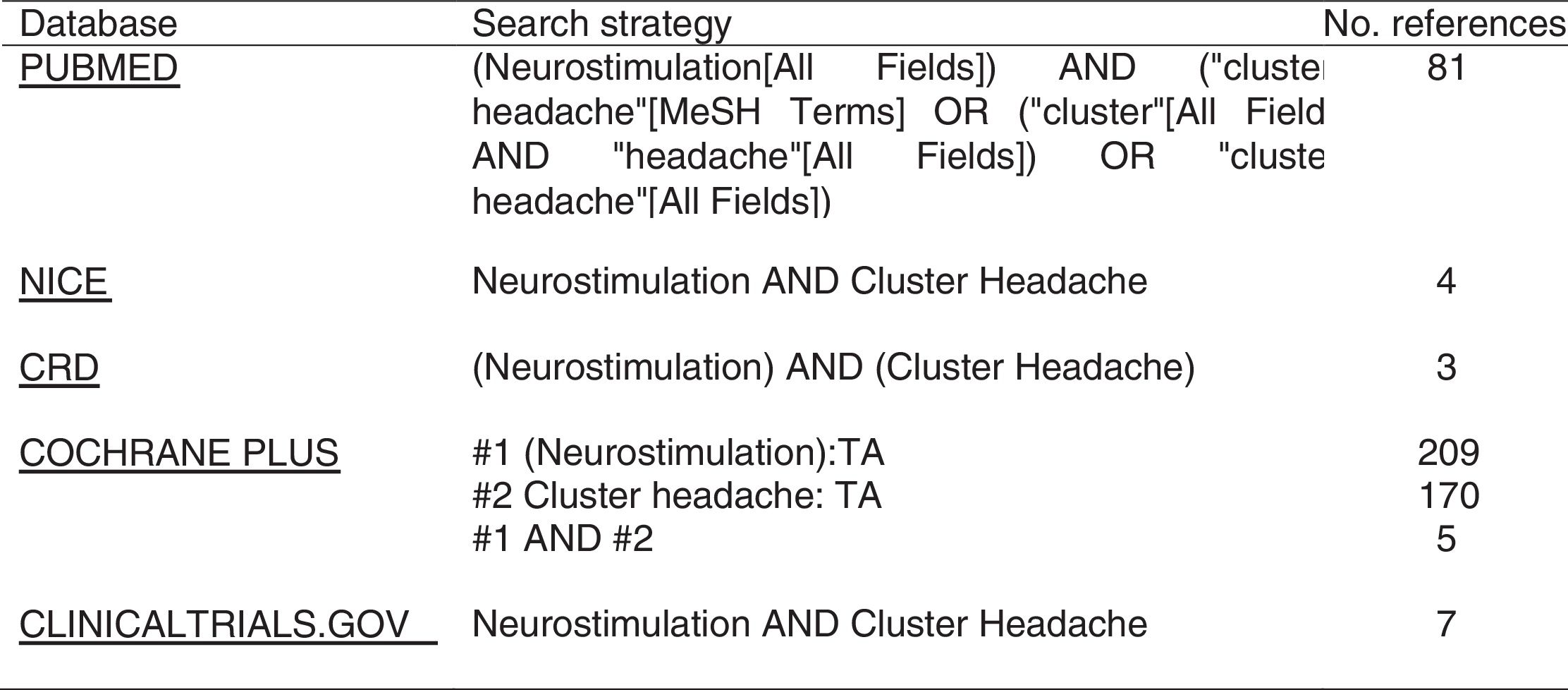

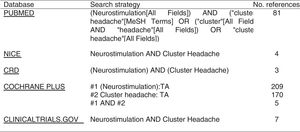

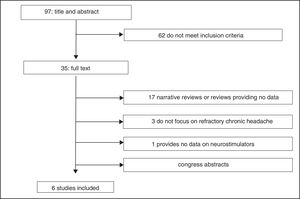

DevelopmentWe conducted a systematic literature review on several databases (Fig. 1). The search strategy used both free text searching and controlled vocabulary, with each term adapted to the thesaurus used for each database (Fig. 1). We also searched the Internet and the websites of national and international health technology assessment agencies for health technology reports. Furthermore, we manually reviewed the bibliographic references of the studies gathered to identify any articles not returned by the database search. We gathered all studies published before 31 October 2016, regardless of article length or language.

We included randomised clinical trials, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, health technology reports, and clinical practice guidelines for the use of peripheral sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation for refractory chronic CH, providing data on the efficacy or effectiveness of the intervention: percentage of patients reporting reduced pain after the intervention, percentage of patients remaining completely pain-free after the intervention, decrease in attack frequency, quality of life according to the Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) or the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), and adverse reactions to treatment.

We excluded other types of studies, letters to the editor, opinion articles, editorials, duplicate studies, and outdated studies.

Articles were gathered, selected, and reviewed by 2 independent reviewers. The reviewers first read the titles and abstracts of the articles gathered, then read the full texts of those initially meeting the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus with another member of the research group. We created a table with information about the studies included and excluded, specifying the reason for exclusion.

We used the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool to evaluate the methodological quality of systematic reviews, and the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials.

Two independent reviewers gathered the following data: bibliographical data, study characteristics, patient characteristics, characteristics of the intervention, outcome measures related to treatment efficacy/effectiveness, and safety of the procedure.

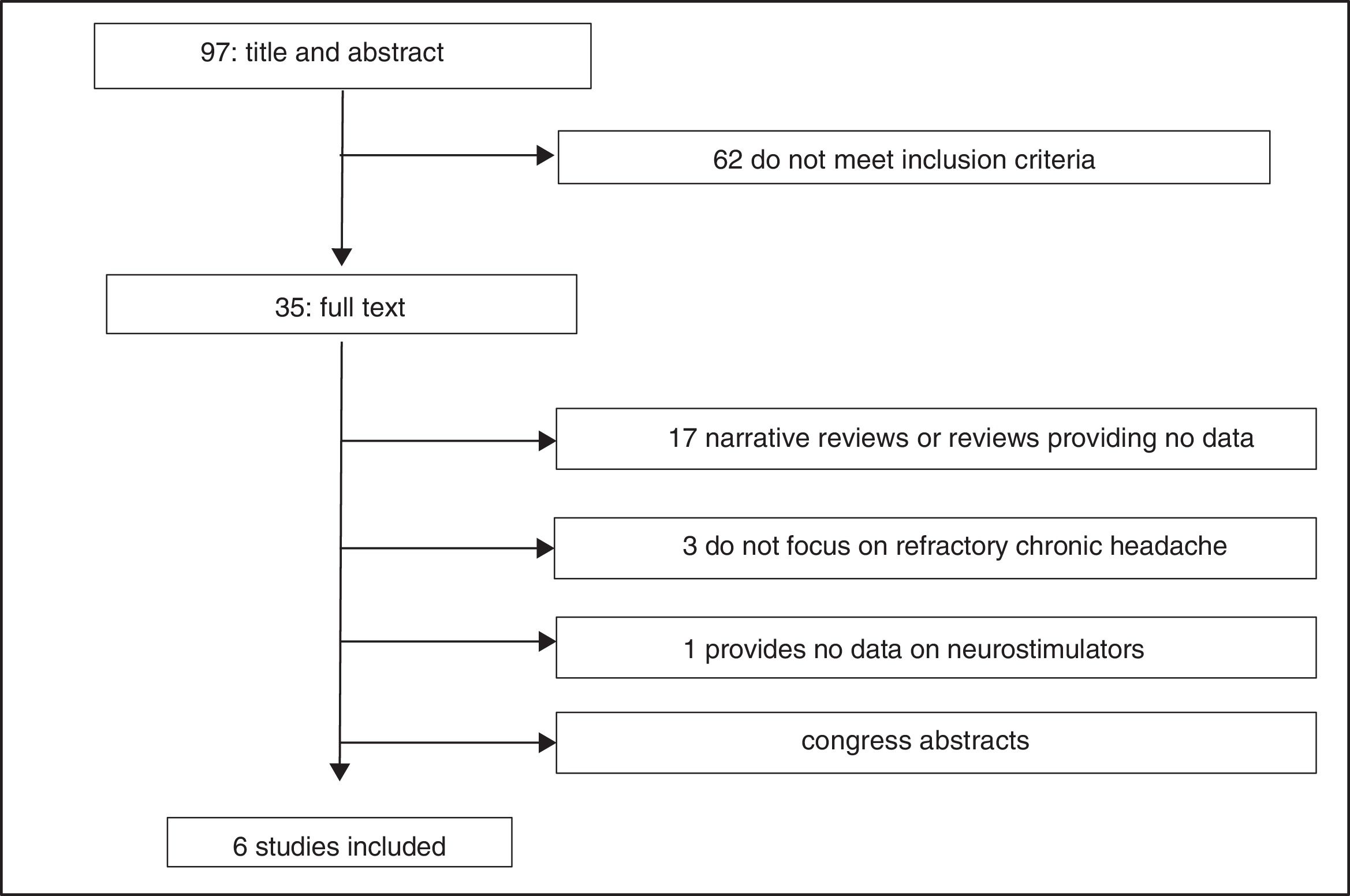

Study selectionWe identified a total of 100 articles (3 were duplicate studies). After reading the titles and abstracts, 62 studies were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria; 29 of the 35 remaining studies were excluded after reading the full text (Fig. 2)10–38: 9 narrative reviews,11,13,15,16,20–22,26,29 8 review articles not providing data on the variables studied,17–19,24,25,27,28,31 8 abstracts,14,32–38 3 studies not focusing on refractory chronic cluster headache,10,12,30 and one study not evaluating peripheral neurostimulation.23 We finally reviewed 6 studies: a health technology report by the Austrian health technology assessment agency, following a systematic review methodology39; a report issued by the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)40; a clinical trial (Pathway CH-1 trial) registered on clinicaltrials.org (FAP 01255813)41; 2 studies42,43 including 24-month follow-up data from the Pathway CH-1 trial, included on clinicaltrials.org (FAP 01616511); and a post-marketing study44 registered on clinicaltrials.org (FAP 01677026) and including patients from the Pathway CH-1 trial. All these studies were funded by Autonomic Technologies, Inc., which manufactures the neurostimulator.

EfficacyBoth the NICE guidelines40 and the Austrian health technology report39 are based on data from the Pathway CH-1 trial,41 which included 32 participants randomly receiving either full, sub-perception, or sham stimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion. The sphenopalatine ganglion was stimulated with the ATI Neurostimulation System, also known as the Pulsante™ SPG Microstimulator.45

The Pathway CH-1 trial41 defined refractory chronic cluster headache as at least 4 episodes of severe headache per week, affecting quality of life and not responding to at least 3 consecutive preventive treatments administered at the maximum tolerable dose. The study comprised 5 stages: pre-implantation baseline, post-implantation stabilisation, therapy titration period (in which electrodes and stimulation parameters were adjusted), experimental period (randomisation to the full, sub-perception, and sham stimulation groups), and an open-label period where all patients received full stimulation.

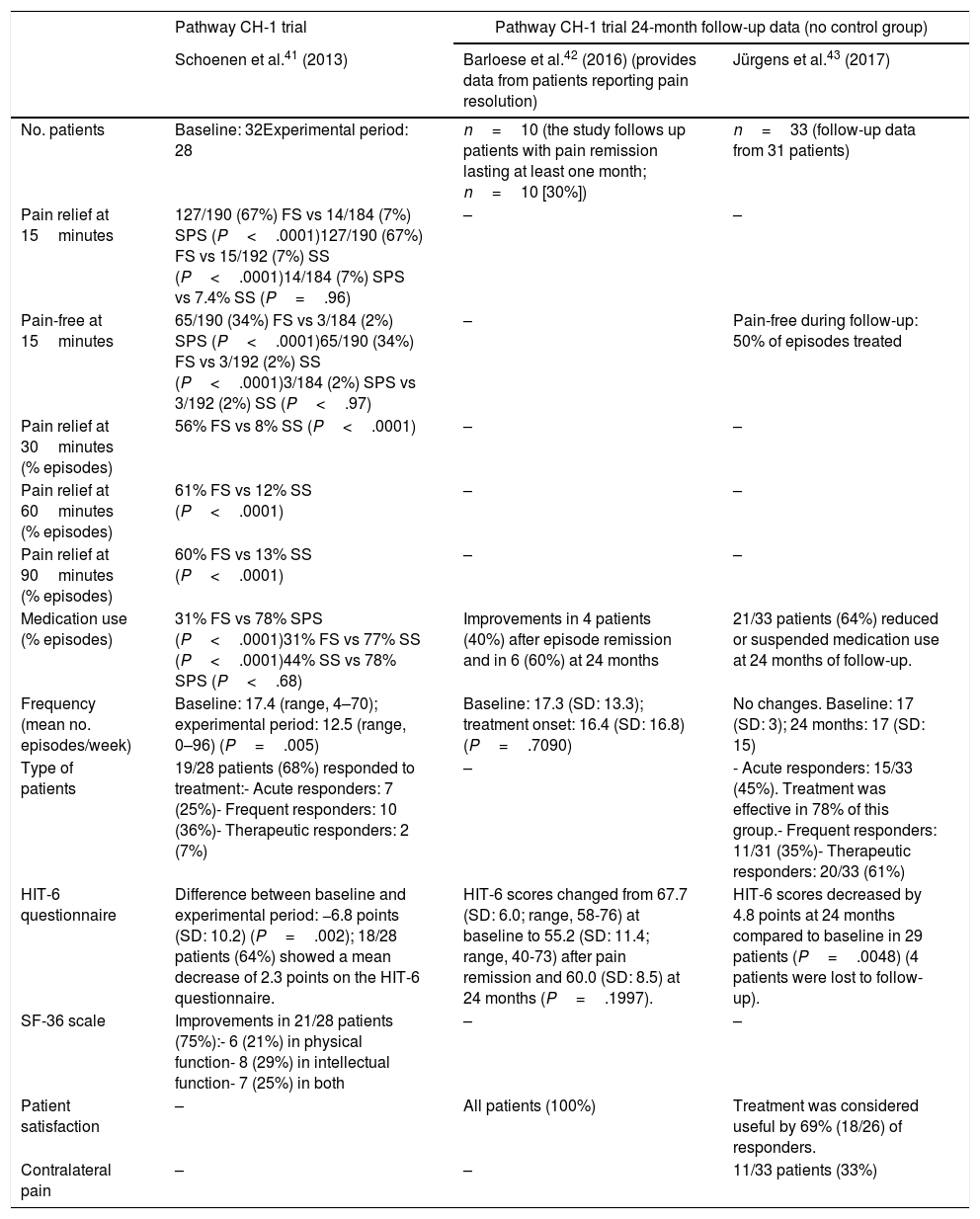

A total of 28 patients continued to the end of the experimental period. The study reports pain relief 15 minutes after stimulation in 67% of episodes treated with full stimulation vs 7% of episodes treated with sub-perception stimulation and 7% of those treated with sham stimulation (P<.0001) (Table 1). Complete resolution of pain at 15minutes was observed in 34% of episodes treated with full stimulation vs 2% of those treated with sub-perception stimulation and 2% of those treated with sham stimulation (P<.0001). Pain decreased at 30, 60, and 90 minutes of neurostimulation in 56%, 61%, and 60%, respectively, of episodes treated with full stimulation, vs 8%, 12%, and 13% of those treated with sham stimulation (P<.0001). Attack frequency in the 28 patients completing the experimental period decreased from a mean of 17.4 to 12.5 episodes per week (P=.005). Sixty-eight percent of patients responded to neurostimulation: 25% presented pain relief in ≥ 50% of episodes, 36% presented a ≥ 50% decrease in attack frequency, and 7% presented both. Medication was administered during the acute phase in 31% of episodes treated with full stimulation vs 78% of those treated with sub-perception stimulation and 77% of those treated with sham stimulation (P<.0001). HIT-6 scores decreased by a mean (SD) of 6.8 (10.2) points between baseline and the experimental period (P=.002). Quality of life (SF-36 scores) improved in 75% of patients: physical function in 21%, intellectual function in 29%, and both dimensions in 25%.

Efficacy results from the Pathway CH-1 trial and 24-month follow-up data.

| Pathway CH-1 trial | Pathway CH-1 trial 24-month follow-up data (no control group) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Schoenen et al.41 (2013) | Barloese et al.42 (2016) (provides data from patients reporting pain resolution) | Jürgens et al.43 (2017) | |

| No. patients | Baseline: 32Experimental period: 28 | n=10 (the study follows up patients with pain remission lasting at least one month; n=10 [30%]) | n=33 (follow-up data from 31 patients) |

| Pain relief at 15minutes | 127/190 (67%) FS vs 14/184 (7%) SPS (P<.0001)127/190 (67%) FS vs 15/192 (7%) SS (P<.0001)14/184 (7%) SPS vs 7.4% SS (P=.96) | – | – |

| Pain-free at 15minutes | 65/190 (34%) FS vs 3/184 (2%) SPS (P<.0001)65/190 (34%) FS vs 3/192 (2%) SS (P<.0001)3/184 (2%) SPS vs 3/192 (2%) SS (P<.97) | – | Pain-free during follow-up: 50% of episodes treated |

| Pain relief at 30minutes (% episodes) | 56% FS vs 8% SS (P<.0001) | – | – |

| Pain relief at 60minutes (% episodes) | 61% FS vs 12% SS (P<.0001) | – | – |

| Pain relief at 90minutes (% episodes) | 60% FS vs 13% SS (P<.0001) | – | – |

| Medication use (% episodes) | 31% FS vs 78% SPS (P<.0001)31% FS vs 77% SS (P<.0001)44% SS vs 78% SPS (P<.68) | Improvements in 4 patients (40%) after episode remission and in 6 (60%) at 24 months | 21/33 patients (64%) reduced or suspended medication use at 24 months of follow-up. |

| Frequency (mean no. episodes/week) | Baseline: 17.4 (range, 4–70); experimental period: 12.5 (range, 0–96) (P=.005) | Baseline: 17.3 (SD: 13.3); treatment onset: 16.4 (SD: 16.8) (P=.7090) | No changes. Baseline: 17 (SD: 3); 24 months: 17 (SD: 15) |

| Type of patients | 19/28 patients (68%) responded to treatment:- Acute responders: 7 (25%)- Frequent responders: 10 (36%)- Therapeutic responders: 2 (7%) | – | - Acute responders: 15/33 (45%). Treatment was effective in 78% of this group.- Frequent responders: 11/31 (35%)- Therapeutic responders: 20/33 (61%) |

| HIT-6 questionnaire | Difference between baseline and experimental period: −6.8 points (SD: 10.2) (P=.002); 18/28 patients (64%) showed a mean decrease of 2.3 points on the HIT-6 questionnaire. | HIT-6 scores changed from 67.7 (SD: 6.0; range, 58-76) at baseline to 55.2 (SD: 11.4; range, 40-73) after pain remission and 60.0 (SD: 8.5) at 24 months (P=.1997). | HIT-6 scores decreased by 4.8 points at 24 months compared to baseline in 29 patients (P=.0048) (4 patients were lost to follow-up). |

| SF-36 scale | Improvements in 21/28 patients (75%):- 6 (21%) in physical function- 8 (29%) in intellectual function- 7 (25%) in both | – | – |

| Patient satisfaction | – | All patients (100%) | Treatment was considered useful by 69% (18/26) of responders. |

| Contralateral pain | – | – | 11/33 patients (33%) |

FS: full stimulation; HIT-6: Headache Impact Test-6; SF-36: 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SPS: sub-perception stimulation; SS: sham stimulation.

Two studies, including 33 patients, published the 24-month follow-up results of the Pathway CH-1 trial.42,43 The first study monitored 10 patients presenting pain remission for at least one month after sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation, reporting the following results: 30% of patients presented at least one episode of pain remission lasting a minimum of one month; the first remission period started a mean of 134 (86) days after the procedure (range, 21-272); the longest remission period lasted a mean of 149 (97) days (range, 62-322); and 60% of patients presenting pain remission had reduced their consumption of preventive drugs at 24 months (Table 1).42 HIT-6 scores were lower after pain remission than at baseline: 67.7 (6.0) at baseline vs 55.2 (11.4) after remission (P=.0118) and 60.0 (8.5) at 24 months (P=.1997). Improvements remained 24 months post-implantation; all patients presenting pain remission were satisfied with the procedure.

The study by Jürgens et al.43 gathered 24-month follow-up data from 33 patients (Table 2) reporting complete resolution of pain in 50% of episodes. The benefits of treatment were still observable at 24 months in 64% of patients. Mean attack frequency in this sample did not change between baseline and follow-up (17 [3] vs 17 [15]). At 24 months, 45% of patients were acute responders and 35% were frequency responders; a total of 61% of patients were responders. HIT-6 scores decreased by 4.8 points compared to baseline in the 29 patients completing the questionnaire (P=.0048). Treatment was found to be useful by 69% of patients; during the 24-month period, 33% of patients reported CH episodes contralateral to microstimulator implantation.

Adverse reactions from the time of device implantation to the end of the experimental period (Pathway CH-1 trial).

| Author (year) | Schoenen et al.41 (2013) | |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse reactions | Within 30 days of implantation | More than 30 days after implantation |

| Total no. adverse reactions | 92 in 32 patients | 36 in 32 patients |

| No. adverse reactions (%), no. patients (%), no. cases resolved (%) | ||

| Lead adjustment/device removal | – | 5 (14), 5 (16), 5 (100) |

| Lead migration/device removal | 1 (1), 1 (3), 1 (100) | – |

| Sensory alterations (including localised sensory loss, hypoaesthesia, paraesthesia, dysaesthesia, and allodynia) | 32 (35), 26 (81), 15 (58) | 6 (17), 5 (16), 3 (60) |

| Pain (face, cheeks, gums, temporomandibular joint, periorbital area, nose, or incision site) | 15 (16), 12 (38), 12 (100) | 6 (17), 6 (19), 3 (50) |

| Headache | 4 (4), 3 (9), 3 (100) | 3 (8), 3 (9), 1 (33) |

| Toothache/sensitivity | 5(5), 5 (16), 4 (80) | 1 (3), 1(3), 1 (100) |

| Swelling | 8(9), 7 (22), 6 (86) | – |

| Swelling and pain (after surgery) | 3 (3), 3 (9), 3 (100) | – |

| Trismus | 5 (5), 5 (16), 4 (80) | – |

| Dry eyes | 3 (3), 3 (9), 1 (33) | 1 (3), 1 (3), – |

| Paraesthesia | 2 (2), 2 (6), 1 (50) | – |

| Infection | 2 (2), 2 (6), 2 (100) | 1 (3), 1 (3), 1 (100) |

| Haematoma | 3 (3), 3 (9), 3 (100) | – |

| Decrease in autonomic symptoms (nasal congestion, tearing) during attacks | 1 (1), 1 (3), 1 (100) | – |

| Facial asymmetry | 1 (1), 1 (3), 1 (100) | 2 (6), 2 (6), – |

| Tearing | 1 (1), 1 (3), 1 (100) | – |

| Conjunctivitis | – | 2 (6), 1 (3), 1 (50) |

| Itching | – | 1 (3), 1 (3), 1 (100) |

| Other | 6 (7), 6 (19), 4 (67) | 8 (22), 8 (25), 5 (63) |

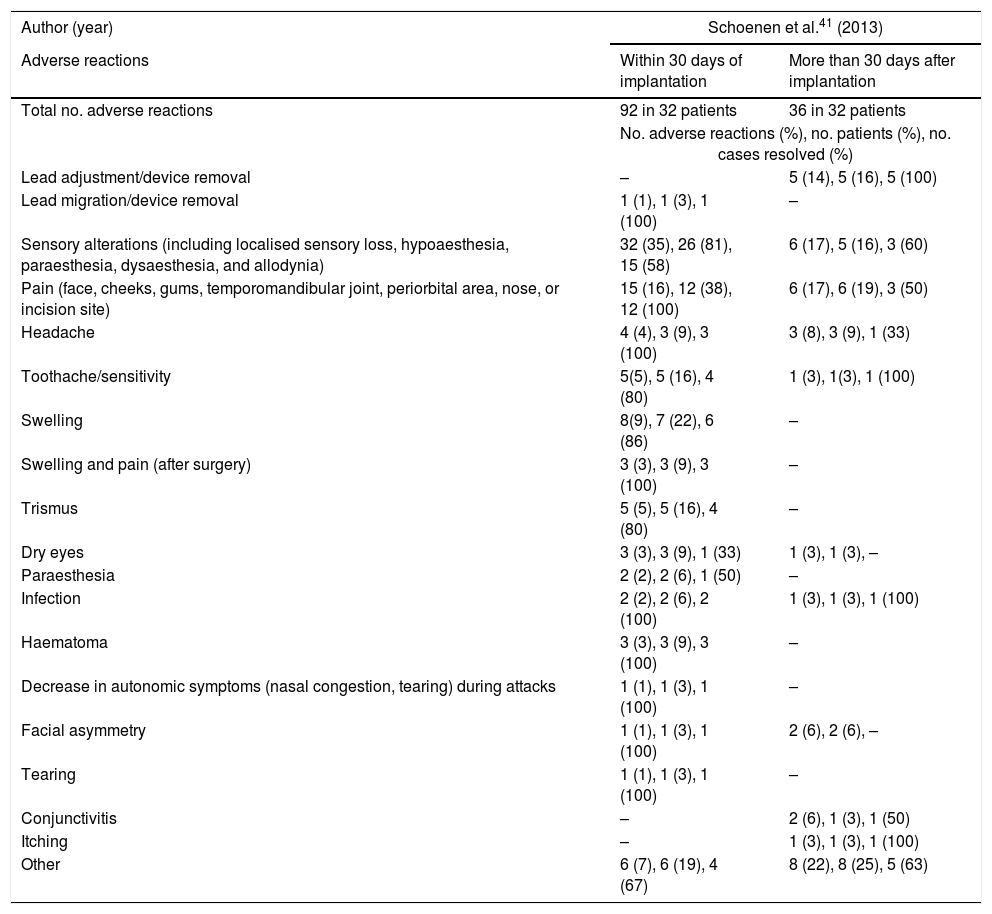

The Pathway CH-1 trial reported 128 different adverse events in 32 patients (Table 2).41 In one patient, the microstimulator had to be removed within 30 days of implantation. In 16% of patients, the microstimulator lead location had to be adjusted or the device removed between 30 days and one year after implantation. Sensory alterations (including localised sensory loss, hypoaesthesia, paraesthesia, dysaesthesia, and allodynia) were observed in 81% of patients within 30 days of device implantation; symptoms resolved in 58% of these patients. Sixteen percent of patients reported sensory alterations 30 days to one year post-implantation, with symptoms resolving in 60% of these. Thirty-eight percent of patients reported pain (face, cheeks, gums, temporomandibular joint, periorbital area, nose, or incision site) within 30 days of implantation. The study provides no data on pain intensity; symptoms resolved in all patients. Nineteen percent of patients reported pain 30 days to one year post-implantation; symptoms resolved in 50% of cases. Nine percent of patients presented headache other than CH within 30 days of the procedure; symptoms resolved in all cases. Furthermore, 9% of patients reported headache other than CH between 30 days and one year after device implantation, with symptoms resolving in 33% of cases. Swelling was observed in 22% of patients within 30 days of the procedure, resolving in 86% of cases.

Sixteen percent of patients showed trismus within 30 days of the procedure; symptoms resolved in 80% of cases. Nine percent of patients reported dry eyes within 30 days of the procedure, with symptoms resolving in 33% of cases. This symptom was reported by 3% of patients between 30 days and one year post-implantation and did not resolve during the follow-up period; 6% presented mild paraesthesia of the nasolabial muscles within 30 days of device implantation, with symptoms resolving in half. Two patients (6%) presented infections within 30 days of the procedure; this was successfully managed with antibiotics in both cases.

Other adverse reactions recorded in the first 30 days after implantation included haematoma, improvement of autonomic symptoms during attacks, and facial asymmetry; these symptoms resolved in most patients. Adverse reactions reported between 30 days and one year post-implantation included conjunctivitis and itching, which resolved in most patients (Table 2).

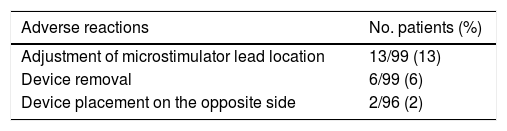

The post-marketing study44 included 99 patients: the 32 patients of the Pathway CH-1 trial,41 11 continued-access Pathway CH-1 patients, and the 56 participants in the Pathway R-1 trial. The study gathered data on adverse events recorded during the perioperative period (30 days post-implantation) (Table 3). Furthermore, it provided information on follow-up procedures: placement of an additional neurostimulator on the opposite side of the face (n=2), adjustment of the microstimulator lead location within the pterygopalatine fossa to better target the sphenopalatine ganglion (n=13), and device removal for other reasons (n=5).

Perioperative adverse reactions (30 days post-implantation) listed in the patient registry published by Assaf et al.44 (n=99).

| Adverse reactions | No. patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Adjustment of microstimulator lead location | 13/99 (13) |

| Device removal | 6/99 (6) |

| Device placement on the opposite side | 2/96 (2) |

| No. adverse reactions (%) | No. patients (%) | No. adverse reactions resolved (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. adverse reactions | 258 (100) | 80 (81) | 167 (65) |

| Sensory alterations | 95 (37) | 66 (67) | 44 (46) |

| Pain or swelling | 79 (31) | 47 (47) | 63 (80) |

| Trismus | 8 (3) | 8 (8) | 6 (75) |

| Limited jaw movement | 6 (2) | 6 (6) | 6 (100) |

| Dry eyes | 5 (2) | 5 (5) | 2 (40) |

| Facial asymmetry | 5 (2) | 5 (5) | 3 (60) |

| Infectiona | 5 (2) | 5 (5) | 4 (80) |

| Haematoma | 4 (2) | 4 (4) | 4 (100) |

| Allodynia | 3 (1) | 3 (3) | 3 (100) |

| Bradycardia during surgery | 3 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (100) |

| Paraesthesiab | 3 (1) | 3 (3) | 1 (33) |

| Sensation of implant | 3 (1) | 3 (3) | 2 (67) |

| Taste alterations | 3 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (67) |

| Diminished gag reflex | 2 (0.8) | 2 (2) | 1 (50) |

| Epistaxis | 2 (0.8) | 2 (2) | 2 (100) |

| Ocular damagec | 2 (0.8) | 2 (2) | 2 (100) |

| Nausea | 2 (0.8) | 2 (2) | 2 (100) |

| Paind | 2 (0.8) | 2 (2) | 1 (50) |

| Rhinorrhoea | 2 (0.8) | 3 (3)e | 1 (50) |

| Toothache | 2 (0.8) | 2 (2) | 2 (100) |

| Tongue biting | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1) | 1 (100) |

| Bleeding | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1) | 1 (100) |

| Blood in saliva | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Difficulty swallowing | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 18 (7) | 18 (18) | 11 (61) |

Infection: nose/sinusitis; incision site: resolved with antibiotics; mouth: resolved with antibiotics; incision site: resulted in device removal, resolved with antibiotics; scar opening: resolved with antibiotics.

Sensory alterations were the most frequent surgical sequelae (affecting 67% of patients), with 95 different sensory alterations reported; 44 resolved in a mean of 104 days (range, 12-313). Forty-seven percent of patients reported pain/swelling, with a total of 79 events; 63 of these resolved in a mean of 68 days (range, 0-312). Patients rated 92% of events as mild or moderate by patients themselves according to their impact on the activities of daily living. Twenty-nine of the 32 patients included in the Pathway CH-1 trial completed a self-assessment questionnaire at 18 months post-implantation: 86% regarded the effects of surgery as tolerable and 90% indicated that they would make the same decision again to treat CH with sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation.

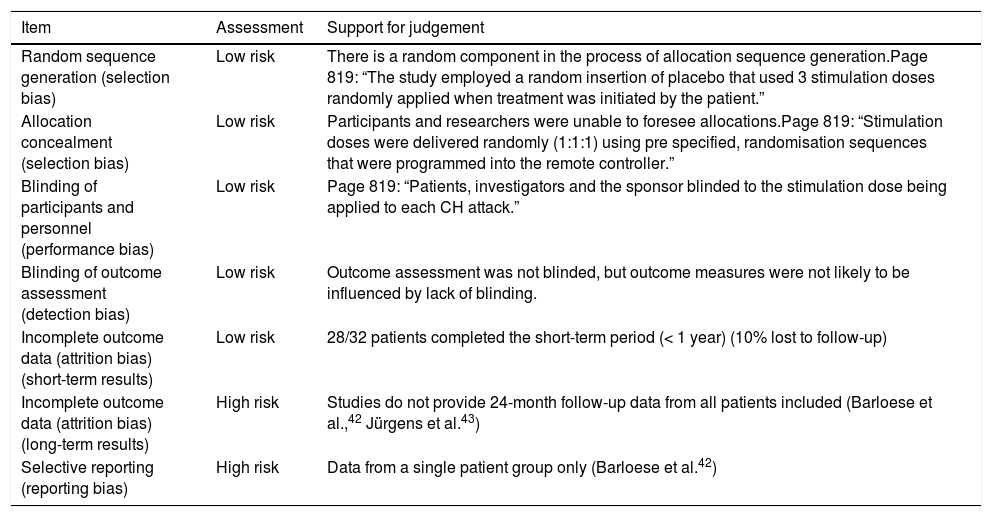

Bias and methodological qualityAccording to the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials, the Pathway CH-1 trial41 had a low risk of bias in some domains (Table 4). However, the studies providing data on long-term follow-up of these patients had a high risk of bias for long-term data and selective reporting of outcomes, since they gathered data from a subgroup of the patient sample.

| Item | Assessment | Support for judgement |

|---|---|---|

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | There is a random component in the process of allocation sequence generation.Page 819: “The study employed a random insertion of placebo that used 3 stimulation doses randomly applied when treatment was initiated by the patient.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants and researchers were unable to foresee allocations.Page 819: “Stimulation doses were delivered randomly (1:1:1) using pre specified, randomisation sequences that were programmed into the remote controller.” |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Page 819: “Patients, investigators and the sponsor blinded to the stimulation dose being applied to each CH attack.” |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Outcome assessment was not blinded, but outcome measures were not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) (short-term results) | Low risk | 28/32 patients completed the short-term period (< 1 year) (10% lost to follow-up) |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) (long-term results) | High risk | Studies do not provide 24-month follow-up data from all patients included (Barloese et al.,42 Jürgens et al.43) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Data from a single patient group only (Barloese et al.42) |

The Austrian health technology report39 is of good methodological quality, scoring 8 out of 10 according to the AMSTAR tool: it has an “a priori” design, at least 2 individuals selected the studies and gathered data, the search strategy was comprehensive, publication type and status were not used as inclusion criteria, the characteristics of the studies included are stated, the scientific quality of the studies included was assessed and documented, scientific quality was considered in formulating conclusions, and conflicts of interest are stated, although the study does not provide a list of all studies included and excluded.

DiscussionOur literature review analyses the currently available evidence on the efficacy and safety of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation as a new treatment alternative for patients with refractory chronic CH. Despite the low incidence of refractory chronic CH, sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation is a major step forward in the treatment of drug-resistant CH as it represents an alternative to surgery, which is frequently associated with severe complications.8

Although cohort and case–control studies may provide complementary data, our objective was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation; to that end, we included clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses, as these methodologies provide higher quality data. Regarding safety, we did include a patient registry with data on potential adverse reactions to sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation.

Our literature search identified studies analysing the safety and effectiveness of peripheral stimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion for the treatment of chronic CH. However, the information provided by these studies mainly came from patients included in a single clinical trial. The trial lasted one year and included 32 patients with refractory chronic CH. However, the experimental, randomised, sham-controlled phase of the study lasted only 3-8 weeks and was completed by 28 patients only.41 Twenty-four-month follow-up data from 33 patients42,43 (vs 32 patients in the Pathway CH-1 trial) only provide data on some indicators of treatment efficacy.

The post-marketing study of 99 patients44 was included in the review because it included the 32 patients from the Pathway CH-1 trial. The study focuses on adverse reactions to treatment within 30 days of device implantation. Limited information is available on the efficacy and safety of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation for chronic CH.

Sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation is a viable, easy-to-use treatment alternative.45 However, clinical trial data show that some patients required adjustment of the microstimulator lead location or device removal within one year of implantation.41 The post-marketing study reports that 13 patients required adjustment of the microstimulator lead location and 5 required removal of the device during the first days post-intervention.44 Reasons for removal of the device included pain secondary to maxillary nerve involvement, device displacement, incorrect initial device placement, and infection at the implantation site.40 It is therefore necessary to exercise caution and to monitor the procedure.40

Regarding the efficacy of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation, the clinical trial reported statistically significant improvements in patients receiving full stimulation (pain relief or resolution; decrease in attack frequency or medication use), compared to those receiving sub-perception or sham stimulation. The trial also reports significant improvements in HIT-6 and SF-36 scores. Although the results are promising, they should be interpreted with caution: these data are from a single clinical trial with a small number of patients (some of whom dropped out), a short follow-up period, and uncertain blinding (patients may have been aware of the stimulation dose received).41 Furthermore, patients may present periods of spontaneous remission of chronic CH.42 Improvements were observed at 24 months compared to baseline. However, the number of patients is limited and follow-up data are scarce.42,43 Cases of unexplained contralateral CH have been reported during patient follow-up; further research is therefore needed into the effects of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation.43

Regarding safety, the studies reviewed report a wide range of adverse reactions within 30 days of device implantation. In fact, 81% of the patients included in the clinical trial presented sensory alterations, and a high percentage of patients reported pain or swelling during that period. Most of these reactions resolved, however.41 Although the number of complications decreases after the 30-day mark, a substantial percentage of patients continue to present adverse reactions to treatment. According to the post-marketing study,44 over half of patients present some type of adverse reaction, although most are considered mild or moderate. Some authors consider that although the procedure is associated with multiple adverse reactions, these are comparable to those of such other oral surgery procedures as tooth extractions, sinus surgery, and dental implant placement.44 Regarding long-term safety, the studies providing 24-month follow-up data do not include information about adverse events. Only Jürgens et al.43 report mild or moderate adverse reactions, resolving in 2–3 months.

The efficacy and safety results of these studies have a number of limitations. According to the NICE guidelines,40 clinical trials should thoroughly describe patient selection criteria, patient selection should be performed by a team of experts specialising in pain management, and the study should provide detailed data on stimulation intensity and duration, medication use, quality of life, and the effect on symptoms. Furthermore, the studies included in our review are not independent; we found no studies evaluating the efficacy of neurostimulation as compared to other medical or surgical treatments, which would have helped evaluate the efficacy of the procedure. Although some authors report the long-term results of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation,42 the longest follow-up period described in the literature is 24 months; the long-term data available to date are therefore insufficient.

Health technology reports evaluating the efficacy and safety of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulators39,40 underscore the frequency of adverse reactions and even the need for removal of the device, concluding that the procedure should only be performed for research purposes.40 Based on the available evidence, the Austrian health technology report recommends that the procedure not be included in the list of medical resources offered by the Austrian healthcare system.39 In our view, the 24-month follow-up data available are not sufficient to challenge these conclusions.

Most patients were satisfied with the intervention42 and found the treatment useful.43 According to the results of a self-assessment questionnaire completed at 18 months post-implantation, 90% of patients would make the same decision again to treat CH with sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation.44 Peripheral sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation may be the only treatment alternative for refractory chronic CH, since some patients do not respond to standard treatments.46 Patient involvement and written informed consent are essential in choosing this treatment.40

ConclusionsThe available evidence on the efficacy of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation for refractory chronic CH is mainly from a single clinical trial, which followed up a small patient sample over a short period. Although the studies included in this review have a number of limitations, are not independent, and do not evaluate the efficacy of the stimulator in comparison with other medical or surgical treatments, sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation may constitute the only treatment alternative for patients with refractory chronic CH.

Regarding treatment efficacy, the studies reviewed report positive outcomes in terms of pain relief, attack frequency, medication use, patient satisfaction, and quality of life. Some patients showed positive results at 24 months compared to baseline, although follow-up data are scarce.

Regarding safety, patients presented numerous adverse reactions within 30 days of the procedure. The device had to be removed in some cases. No long-term safety data are available.

Efficacy and safety results are promising, despite limited evidence. Further research is needed into the safety and efficacy of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation for patients with refractory chronic CH. When the intervention is indicated, it should be conducted under close supervision and following a research protocol, with careful attention paid to patient written informed consent.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Gómez LM, Polo-deSantos M, Pinel-González A, Oreja-Guevara C, Luengo-Matos S. Revisión sistemática sobre la eficacia y seguridad de los neuroestimuladores periféricos del ganglio esfenopalatino para el tratamiento de la cefalea crónica en racimos refractaria. Neurología. 2021;36:440–450.