Serotonin syndrome (SS) is an infrequent and potentially life-threatening condition caused by excessively increased serotonergic activity in the central nervous system.1 Severity is highly variable, ranging from mild cases that may go undetected to fatal cases (2.5%).2 It is typically caused by the use of serotonergic drugs, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or monoamine oxidase inhibitors. However, it is less well known that it may also be triggered by the onset of treatment with non-serotonergic drugs in patients concomitantly taking antidepressants.3,4 We present the case of a patient with SS induced by amoxicillin–clavulanic acid.

Our patient is a 78-year-old woman with chronic depressive syndrome and arthrosis; her family brought her to the emergency department due to somnolence. She was receiving long-term treatment with several drugs, including 25 mg pregabalin, 100 μg fentanyl patches, 60 mg duloxetine, and 100 mg trazodone. No changes had recently been made to this treatment schedule, although the family could not guarantee proper adherence as the patient took her pills from 2 bottles, where she kept them mixed together. Five days earlier, she had started treatment with amoxicillin–clavulanic acid to treat an infection of the soft tissues of the foot (ingrown toenail). After onset of antibiotic treatment, the patient displayed behavioural changes with a tendency to drowsiness, as well as rigidity in the lower limbs, and very pronounced diaphoresis. Upon her arrival at the emergency department, blood pressure values were within normal ranges (127/74), but she presented tachycardia (117 bpm) and low-grade fever (37.2 °C). A very striking finding of the general examination was generalised excessive sweating; she also displayed mouth dryness, sinus tachycardia, and reddening around the first toenail of the left foot. In the neurological examination, the patient’s level of consciousness was good, but she presented psychomotor restlessness, symmetric hypertonia in the lower limbs with generalised muscle hyperreflexia, and bilateral ankle clonus with no Babinski sign. The complementary studies including blood analysis, urine sediment testing, head CT scan, electrocardiography, and chest radiography revealed no significant alterations. Suspecting probable SS triggered by the use of amoxicillin in the context of long-term treatment with serotonergic drugs, we decided to withdraw the drug, and the patient was admitted for symptomatic management (serum therapy, low-dose benzodiazepines, analgesics, and antipyretics). Progression was very favourable, and 3 days later she had fully recovered.

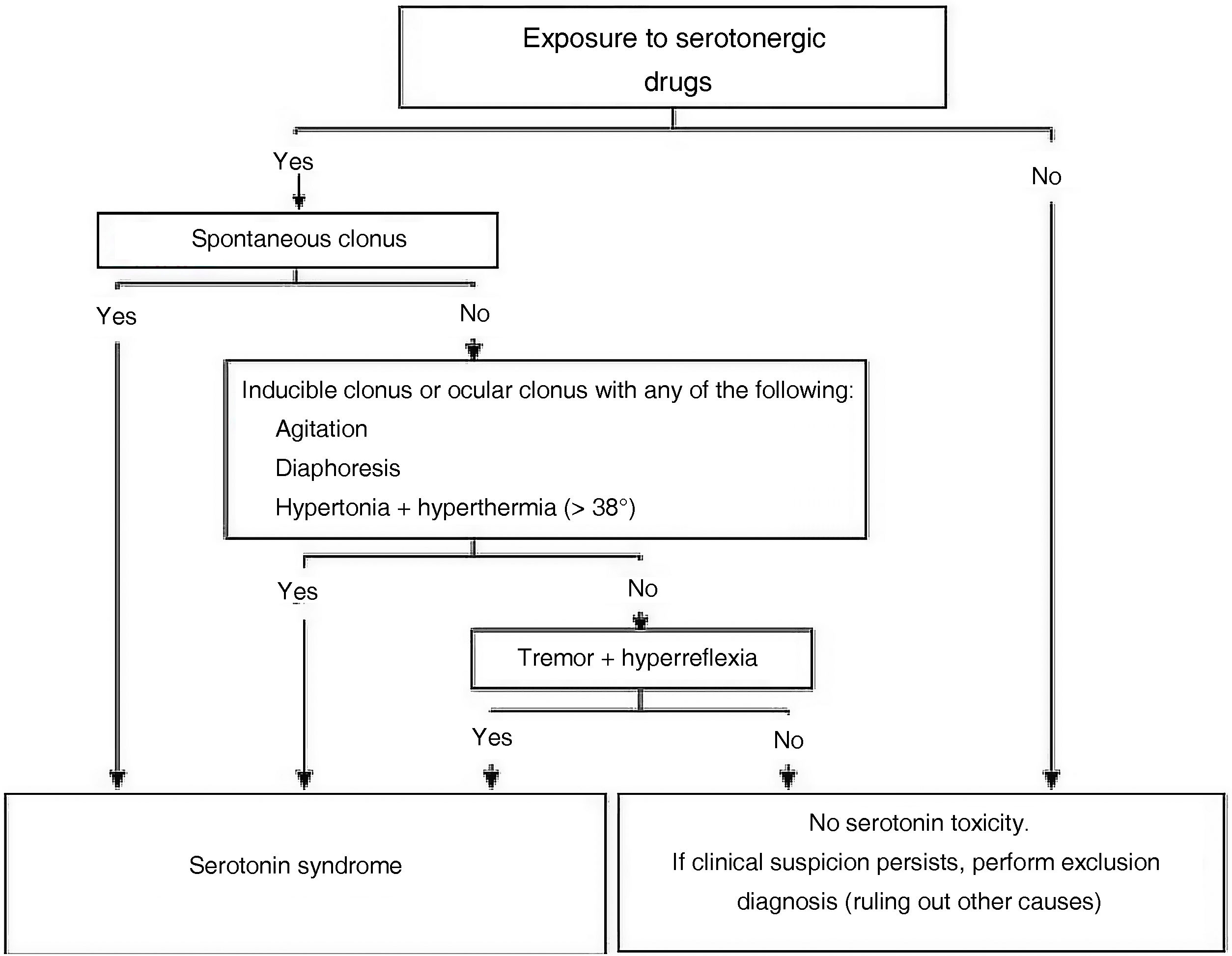

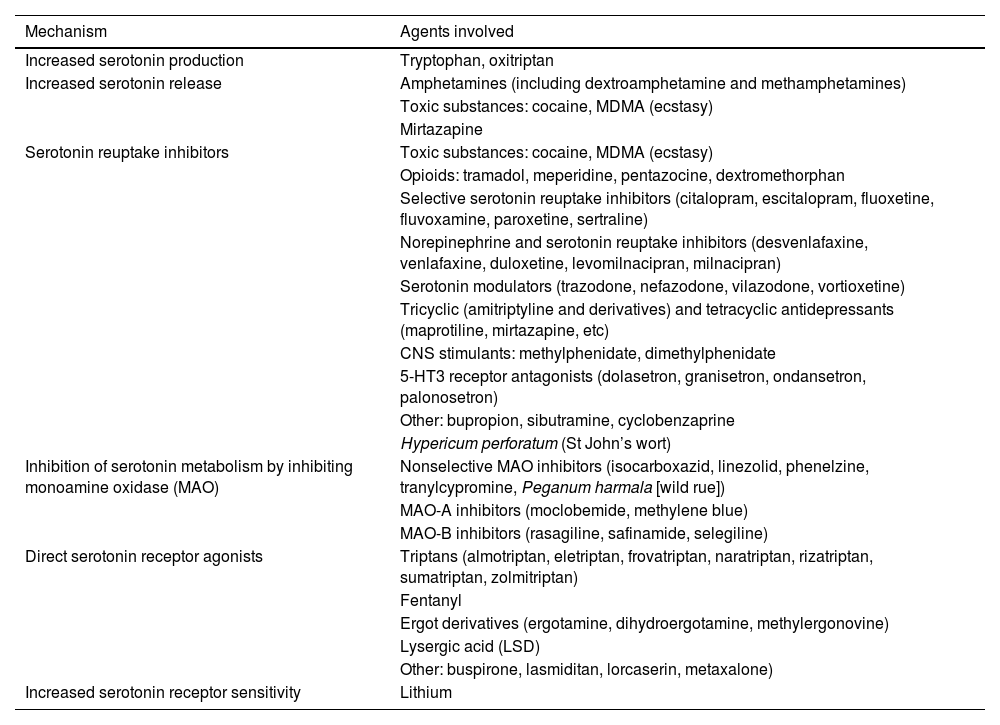

SS is probably an underdiagnosed entity, but it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with any of the symptoms described above (hyperthermia, diaphoresis, rigidity, etc), especially in the context of polymedication or recent changes to treatment schedule.4 Its frequency is highly variable (up to 15% of patients abusing antidepressants), and is greater in elderly and polymedicated patients. Clinical studies describe a classical triad of altered mental state, autonomic nervous system hyperactivity, and neuromuscular disorders (typically more pronounced in the lower limbs). In clinical practice, symptoms are highly variable, and include somnolence, delirium, anxiety, agitation, disorientation, mydriasis, sweating, hyperthermia, diarrhoea and increased peristalsis, hyperreflexia and clonus, ocular clonus, muscle rigidity, and tremor. Severe cases may show rhabdomyolysis, haemodynamic instability, and multiple organ failure. Diagnosis is clinical and is based on the presence of compatible signs and symptoms (Fig. 1),5 exposure to potentially inducing drugs (Table 1), and exclusion of other possible causes. Our patient presented good tolerability to 2 serotonin reuptake inhibitors acting at the presynaptic level (trazodone and duloxetine) and a postsynaptic serotonergic receptor agonist (fentanyl). However, SS was triggered by the introduction of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, although we are unable to rule out poor adherence to the previous treatment schedule. Although the mechanism is not well understood, cases have been reported of patients who were concomitantly taking antidepressants in whom SS was triggered by the onset of drugs without clear serotonergic action.7,8 A total of 86 cases have been reported since 1997 in association with amoxicillin, accounting for 0.1% of the adverse events associated with the drug (86/82 247).9

Algorithm for the diagnosis of serotonin syndrome, adapted from the Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria.6

Action mechanism and agents potentially involved in increased serotonergic activity.10

| Mechanism | Agents involved |

|---|---|

| Increased serotonin production | Tryptophan, oxitriptan |

| Increased serotonin release | Amphetamines (including dextroamphetamine and methamphetamines) |

| Toxic substances: cocaine, MDMA (ecstasy) | |

| Mirtazapine | |

| Serotonin reuptake inhibitors | Toxic substances: cocaine, MDMA (ecstasy) |

| Opioids: tramadol, meperidine, pentazocine, dextromethorphan | |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline) | |

| Norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitors (desvenlafaxine, venlafaxine, duloxetine, levomilnacipran, milnacipran) | |

| Serotonin modulators (trazodone, nefazodone, vilazodone, vortioxetine) | |

| Tricyclic (amitriptyline and derivatives) and tetracyclic antidepressants (maprotiline, mirtazapine, etc) | |

| CNS stimulants: methylphenidate, dimethylphenidate | |

| 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (dolasetron, granisetron, ondansetron, palonosetron) | |

| Other: bupropion, sibutramine, cyclobenzaprine | |

| Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) | |

| Inhibition of serotonin metabolism by inhibiting monoamine oxidase (MAO) | Nonselective MAO inhibitors (isocarboxazid, linezolid, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, Peganum harmala [wild rue]) |

| MAO-A inhibitors (moclobemide, methylene blue) | |

| MAO-B inhibitors (rasagiline, safinamide, selegiline) | |

| Direct serotonin receptor agonists | Triptans (almotriptan, eletriptan, frovatriptan, naratriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan, zolmitriptan) |

| Fentanyl | |

| Ergot derivatives (ergotamine, dihydroergotamine, methylergonovine) | |

| Lysergic acid (LSD) | |

| Other: buspirone, lasmiditan, lorcaserin, metaxalone) | |

| Increased serotonin receptor sensitivity | Lithium |

In conclusion, SS should be considered in patients receiving serotonergic drugs and developing compatible symptoms. The onset of frequently used antibiotics such as amoxicillin may trigger SS, so their prescription should be avoided where possible in patients receiving serotonergic drugs, especially if adherence is not optimally controlled.