Schwannomatosis is the third most frequent type of neurofibromatosis, after neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2 (NF-1 and NF-2). The disease is characterised by the presence of multiple non-intradermal schwannomas in the absence of bilateral vestibular schwannomas, and was first described in the 1990s in a clinical-pathological study of patients with multiple schwannomas not meeting criteria for NF-2.1 Various genetic alterations have since been implicated in the disease; significant examples are germline mutations of the tumour suppressor gene SMARCB1 and loss-of-function mutations in LZTR1; both genes are located on chromosome 22.2,3 From a clinical viewpoint, schwannomatosis presents a significant overlap with NF-2, which greatly hinders the correct diagnosis of these patients; therefore, genetic studies are an important diagnostic tool in case of uncertainty.4

We present the case of a patient with schwannoma of the posterior tibial nerve in whom we detected a novel loss-of-function mutation in LZTR1, underscoring the importance of clinical suspicion of this type of disease in specific cases.

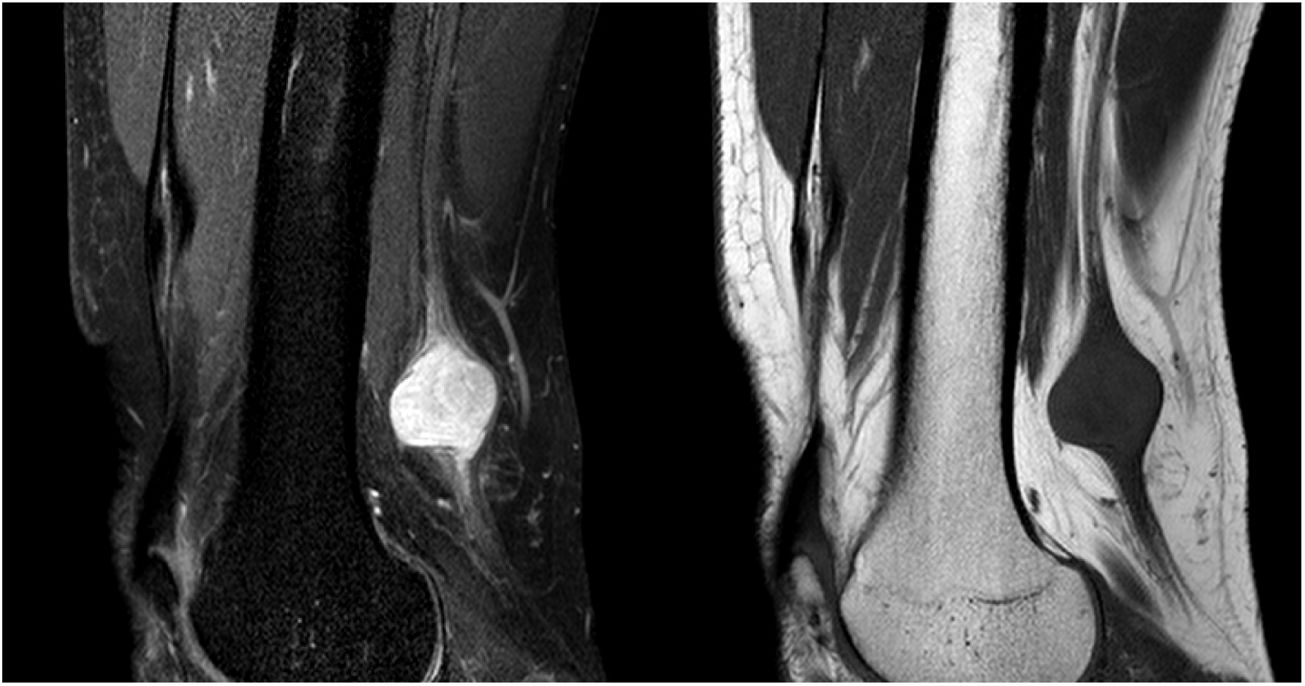

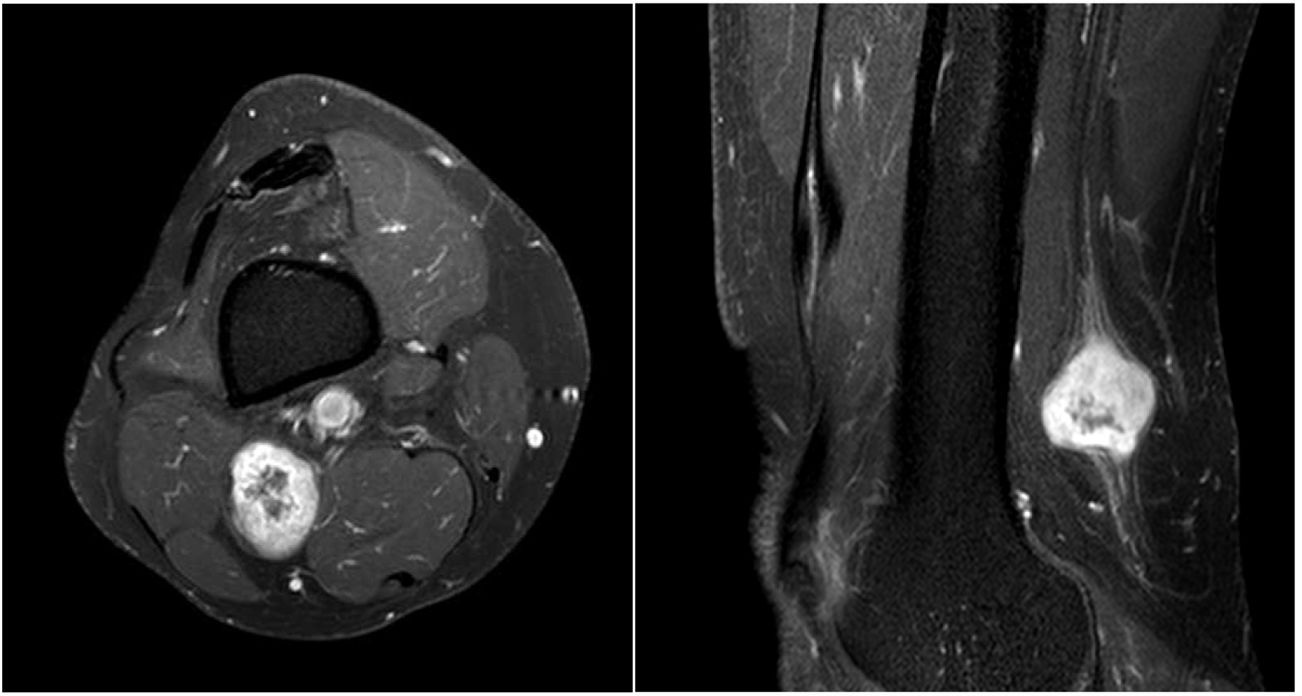

The patient was a 54-year-old man with history of schwannoma of the left median nerve, treated surgically; he was receiving enalapril to treat arterial hypertension. The patient visited the neurology department due 3-year history of neuropathic pain in the left heel and plantar surface, in the territory of the posterior tibial nerve. The patient reported no family history of neurological disease, and his daughter was healthy. Physical and neurological examination revealed no abnormalities, with negative Tinel sign and no palpable masses in any region. The patient provided an MR image of the lumbar spine and an EMG recording, which showed no relevant alterations, and had been assessed on several occasions by the emergency and traumatology departments, with a clinical diagnosis of non-specific pain in the left foot. Based on clinical suspicion, we ordered an MRI study of the left lower limb, which revealed a tumour involving the initial segment of the posterior tibial nerve (Fig. 1 and 2); an anatomical pathology study performed after resection of the mass confirmed the diagnosis of schwannoma. We also requested a high-resolution brain MRI study focusing on both internal auditory canals, which detected no evidence of vestibular nerve involvement. The patient met clinical criteria for schwannomatosis,5 but we were unable to rule out NF-2, which has prognostic and therapeutic consequences. For these reasons, and with a view to providing genetic counselling to his family members, we requested a study of the genes ENG, GDF2, GLMN, GNAQ, HRAS, LZTR1, NF1, NF2, PIK3CA, PTEN, SMAD4, SMARCB1, TEK, TSC1, TSC2, and VHL. The genetic study revealed that the patient was heterozygous for a previously undescribed LZTR1 mutation (c.1203C > G) (p-Y401), which results in a premature stop codon; this finding is compatible with diagnosis of LZTR1-related schwannomatosis.3 The alteration was confirmed with Sanger sequencing; the patient’s family members have not yet been tested.

Fat-suppressed proton density–weighted and T1-weighted sagittal MRI sequences showing a lesion to the superior popliteal fossa, involving the posterior tibial nerve. The lesion is isointense on T1- weighted sequences and presents heterogeneous hyperintensity on proton density–weighted sequences. The entering and exiting nerve can be seen.

This case demonstrates the need to consider atypical or rare causes in patients presenting chronic pain of unknown aetiology; nerve sheath tumours constitute one such cause. Diagnostic delay is common in patients with schwannomatosis due to the rarity of the disease6 and the non-specificity of its symptoms: pain not associated with a palpable mass is the most common symptom.7 Furthermore, family history does not usually provide valuable information, as only 13% of patients have family history of the disease.7 We should also stress the importance of genetic studies for correct diagnosis, as schwannomatosis presents a broad spectrum of phenotypes and is often indistinguishable from NF-2. The latter condition is usually associated with germline mutations, which are detected in over 90% of patients without mosaicism,4 and presents poorer prognosis than schwannomatosis.6 Moreover, both entities usually manifest as multiple cranial meningiomas exclusively; this has given rise to controversy about the need to broaden diagnostic criteria to include genetic testing in the basic diagnostic study.8

This case report contributes a novel LZTR1 mutation, expanding the genetic spectrum of the disease.

FundingThe authors have received no funding for this study.

Please cite this article as: Herrero San Martín A. and Alcalá-Galiano A. Schwannoma del nervio tibial en un paciente con schwannomatosis asociada a una nueva mutación en el gen LZTR1. Neurología. 2020;35:657–659.