Status epilepticus (SE) is a neurological emergency associated with significant mortality and morbidity. We analyse characteristics of this entity in our population.

MethodsData from electronic medical records of adults diagnosed with SE were collected retrospectively from 5 hospitals over 4 years.

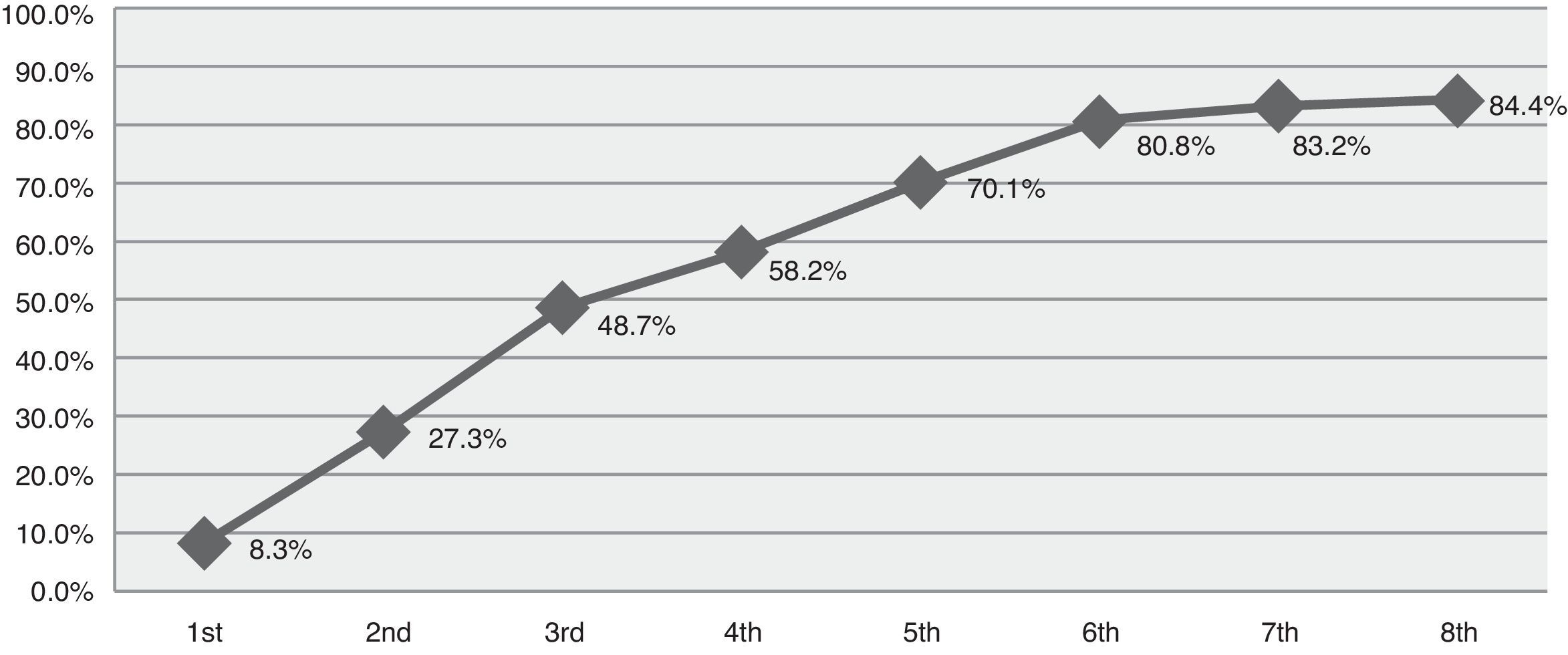

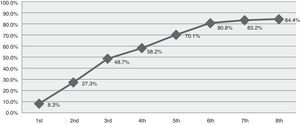

ResultsData reflected 84 episodes of SE in 77 patients with a mean age of 60.3 years. Of this sample, 52.4% had a previous history of epilepsy. Status classification: 47.6% tonic–clonic, 21.4% complex partial, 17.9% partial motor, 6% partial simple, 3.6% myoclonic, and 3.6% subtle SE. Based on the duration of the episode, SE was defined in this study as early stage (up to 30min) in 13.1%, established (30-120min) in 20.2%, refractory (more than 120min) in 41.7%, and super-refractory (episodes continuing or recurring after more than 24h of anaesthesia) in 13.1%. Ten patients (11.9%) died when treatment failed to control SE. The cumulative percentage of success achieved was 8.3% with the first treatment, 27.3% for the second, 48.7% for the third, 58.2% for the fourth, 70.1% for the fifth, 80.8% for the sixth, 83.2% for the seventh, and 84.4% for the eighth.

ConclusionsIn our study, we found that SE did not respond to treatment within 2hours in approximately half the cases and 11.9% of the patients died without achieving seizure control, regardless of the type of status. Half the patients responded by the third treatment but some patients needed as many as 8 treatments to resolve seizures. Using large registers permitting analysis of the different types and stages of SE is warranted.

El estatus epiléptico es una urgencia neurológica asociada a una mortalidad y morbilidad significativa. Analizamos las características en nuestra población.

MétodosSe recogieron los datos de manera retrospectiva de la historia clínica electrónica de adultos con diagnóstico de estatus epiléptico en 5 centros hospitalarios durante 4 años.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron datos de un total de 84 episodios en 77 pacientes, con edad media de 60,3 años. El 52,4% tenían historia previa de epilepsia. Clasificación según el tipo de estatus: 47,6% tónico-clónico; 21,4% parcial complejo; 17,9% parcial motor; 6% parcial simple; 3,6% mioclónico y 3,6% sutil. Si analizamos el momento que finalizó el estatus según las fases definidas para este estudio obtenemos: 13,1% precoz (hasta 30min); 20,2% establecido (entre 30-120min); 41,7% refractario (más de 120min) y 13,1% superrefractario (continúan o recurren después de más de 24h de anestesia). Diez casos (11,9%) fallecieron sin haberse controlado el estatus. El porcentaje acumulativo de éxito alcanzado con el primer tratamiento fue de 8,3%; segundo 27,3%; tercero 48,7%; cuarto 58,2%; quinto 70,1%; sexto 80,8%; séptimo 83,2% y octavo 84,4%.

ConclusionesEn nuestro estudio encontramos que el estatus no se controló en las primeras 2h en casi la mitad de los casos, y un 11,9% fallecieron sin controlarse, sin haber diferencias significativas entre el tipo de estatus. En casi la mitad se logró el control del estatus con el tercer tratamiento, pero en algún caso se precisó hasta 8. Son necesarios registros amplios que permitan analizar el manejo en los distintos tipos y fases.

Status epilepticus (SE) is a neurological condition associated with high morbidity and mortality. Estimated global incidence varies with the population under study and the definition used.2,4,10,20,23 In Europe, incidence of convulsive SE ranges from 3.6 to 6.6 cases per 100000 population, whereas that of nonconvulsive SE ranges from 2.6 to 7.8 cases per 100000 population.3,12,22 According to a recent study conducted in the United States, annual incidence has increased from 3.5 cases per 100000 population in 1979 to 12.5 cases per 100000 population in 2010.5 Despite recent advances in antiepileptic drug research, few randomised clinical trials have been conducted, mainly because of their methodological and ethical complexities. According to published guidelines, treatment may vary from country to country due to differences in drug availability.15,16,21 The purpose of this study is to determine the characteristics of and treatment approaches for the different types of SE in our population.

Material and methodsThis retrospective study involved reviewing electronic medical histories from patients diagnosed with SE –CIE-9 codes 345.2, 345.3, and 345.7– in 5 secondary hospitals providing care to a population of 860000 inhabitants in the Region of Madrid (Spain), between their respective opening dates in 2008 and June 2012. We recorded the following demographic and clinical variables: history of epilepsy, characteristics of SE, treatment, progression, and sequelae. For the purposes of this study, we defined the following stages of SE: early (before the 30-min mark), established (30-120min), refractory (more than 120min), and super-refractory (SE that continues or recurs 24h or more after initiation of anaesthetic therapy). As previous studies have done, we evaluated treatment results based on outcome categories. Success was defined as a drug's ability to achieve complete SE control with no relapses after withdrawal, secondary effects leading to drug discontinuation, or death during treatment. Likewise, we defined 5 categories of failure: initial failure, recurrence, seizures after withdrawal, intolerable side effects, or death during treatment.

We performed a descriptive analysis of the sample. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequency distributions and quantitative variables as measures of central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion (SD or interquartile range), depending on the distribution. To compare qualitative variables we used the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test when more than 25% of the expected values were below 5. For ordinal variables, the hypothesis of ordinal trend of proportions was assessed. Quantitative variables with a normal distribution were compared using the t test; its non-parametric equivalent, the Mann–Whitney U test, was used for variables with non-normal distributions. Type I errors or alpha errors below 0.05 led to rejection of the null hypothesis. Data were analysed with SPSS statistical software version 18 (Chicago, IL).

ResultsPatient characteristicsWe gathered data from a total of 84 episodes of SE corresponding to 77 patients. One patient experienced 4 SE, 4 patients had 2 SE, and the remaining 72 patients experienced a single episode each. Mean age of our sample was 60.3 years (range, 17-97); there were 30 men (39%) and 47 women (61%).

Forty patients (47.6%) had no history of epilepsy before being admitted due to SE. Of the 44 patients (52.4%) with a history of epilepsy, 32 (72.7%) had symptomatic epilepsy, 9 (20.5%) cryptogenic epilepsy, and 3 (6.8%) had idiopathic epilepsy. All patients but one (43; 51.2%) were in treatment with antiepileptic drugs. Of these, 18 were receiving monotherapy (41.9%) and 25, combination therapy (57.8%); 11 patients (25.6%) were taking 2 antiepileptics, 9 (20.6%) were taking 3, and 5 (11.6%) were in treatment with 4.

Characteristics of status epilepticusSE was tonic–clonic in 40 patients (47.6%), complex partial in 18 (21.4%), focal or partial motor in 15 (17.9%), simple partial nonconvulsive in 5 (6%) (simple partial status with no motor symptoms), myoclonic in 3 (3.6%), and subtle in 3. There were no statistically significant differences in the type of SE between patients with and without a history of epilepsy.

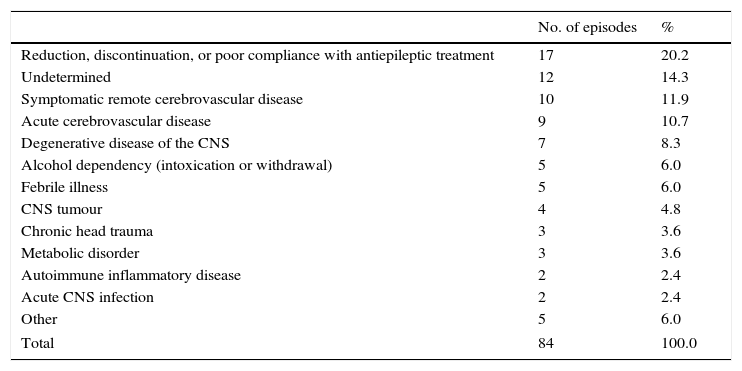

The aetiologies of SE were classified as shown in Table 1. The most frequent causes were reduction, discontinuation, or poor compliance with antiepileptic treatment (20.2%); remote cerebrovascular disease (11.9%); and acute cerebrovascular disease (10.7%). Idiopathic or cryptogenic cases made up 14.3%. Fifty-nine episodes (70.2%) were evaluated with EEG, although the precise time of the procedure was not specified.

Aetiology of status epilepticus.

| No. of episodes | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Reduction, discontinuation, or poor compliance with antiepileptic treatment | 17 | 20.2 |

| Undetermined | 12 | 14.3 |

| Symptomatic remote cerebrovascular disease | 10 | 11.9 |

| Acute cerebrovascular disease | 9 | 10.7 |

| Degenerative disease of the CNS | 7 | 8.3 |

| Alcohol dependency (intoxication or withdrawal) | 5 | 6.0 |

| Febrile illness | 5 | 6.0 |

| CNS tumour | 4 | 4.8 |

| Chronic head trauma | 3 | 3.6 |

| Metabolic disorder | 3 | 3.6 |

| Autoimmune inflammatory disease | 2 | 2.4 |

| Acute CNS infection | 2 | 2.4 |

| Other | 5 | 6.0 |

| Total | 84 | 100.0 |

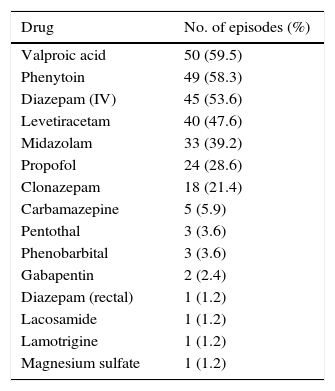

Patients with SE received the following antiepileptic drugs at some point during treatment: valproic acid (50 episodes; 59.52%), phenytoin (49; 58.33%), intravenous diazepam (45; 53.57%), levetiracetam (40; 47.62%), midazolam (33; 39.8%), propofol (24; 28.57%), clonazepam (18, 21.4%), carbamazepine (5; 5.9%), pentothal (3; 3.57%), phenobarbital (3), gabapentin (2; 2.3%), rectal diazepam (1; 1.2%), lamotrigine (1), magnesium sulfate (1), and lacosamide (1) (Table 2).

Drugs used during treatment.

| Drug | No. of episodes (%) |

|---|---|

| Valproic acid | 50 (59.5) |

| Phenytoin | 49 (58.3) |

| Diazepam (IV) | 45 (53.6) |

| Levetiracetam | 40 (47.6) |

| Midazolam | 33 (39.2) |

| Propofol | 24 (28.6) |

| Clonazepam | 18 (21.4) |

| Carbamazepine | 5 (5.9) |

| Pentothal | 3 (3.6) |

| Phenobarbital | 3 (3.6) |

| Gabapentin | 2 (2.4) |

| Diazepam (rectal) | 1 (1.2) |

| Lacosamide | 1 (1.2) |

| Lamotrigine | 1 (1.2) |

| Magnesium sulfate | 1 (1.2) |

The cumulative success rate with each additional drug was 8.3% (first drug), 27.3%, 48.7%, 58.2%, 40.1%, 80.8%, 83.2%, and 84.4% (eighth drug) (Fig. 1). No data were available for 3.7% of the patients.

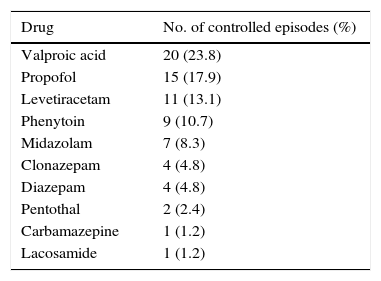

The following drugs delivered SE control: valproic acid (20 episodes; 23.8%), propofol (15; 17.9%), levetiracetam (11; 13.1%), phenytoin (9; 10.7%), midazolam (7; 8.3%), clonazepam (4; 4.8%), diazepam (4), pentothal (2; 2.4%), carbamazepine (1; 1.2%), and lacosamide (1; 1.2%). Ten patients (11.9%) died; treatment failed to control SE in these cases (Table 3). There were no significant differences in the drugs achieving SE control for types of SE.

Eleven SE episodes (13.1%) were controlled in the early stage, 17 (20.2%) in the established stage, 35 (41.7%) in the refractory stage, 11 (13.1%) in the super-refractory stage, and 10 (11.9%) died before SE could be controlled. There were no significant differences in the stage in which seizure control was achieved for different types of SE. Adverse drug effects occurred during 21 episodes (25%): only one in 16 episodes (19%), 2 in 4 episodes (4.8%), and 3 in one case (1.2%).

Progression and prognosisForty episodes (47.6%) led to the patient being admitted to the ICU; mean duration of hospital stay was 8.73 days (median, 5; range, 1-55). Broken down by seizure type, 62.5% of the episodes of tonic–clonic SE required ICU care, compared to 38.9% of the episodes of complex partial SE (P=.004) and 26.7% of the episodes of partial motor SE (P=.039).

Thirty-two episodes (38.1%) required intubation of the patient lasting a mean of 7.75 days (median, 4.5; range, 1-55). Fifty-five percent of the episodes of tonic–clonic SE resulted in an intubation, compared to 13.3% of the episodes of partial motor SE (P=.013) and 27.8% of complex partial SE episodes (differences were not significant).

Forty-six episodes of SE (54.8%) were associated with systemic complications: these were more frequent in tonic–clonic SE (65.5%) than in complex partial SE (35.3%) (P=.038).

Fifteen patients (17.9%) died while hospitalised. Regarding patients’ neurological status at discharge, 55 episodes (65.5%) resolved completely, 4 episodes (4.8%) left mild neurological impairment, one (1.2%) left moderate neurological deficits, and 5 (6%) resulted in severe neurological impairment; final neurological status was not assessed in 3 (3.6%). There were no significant differences in mortality or sequelae for different types of SE.

Patients who died were significantly older than the rest (mean of 75.8 vs 55.4). Most of these patients had not been admitted to the ICU (86.7%) and 80% had experienced systemic complications, compared to only 49.3% of survivors (P=.038). The aetiologies of SE in the patients who died were as follows: infectious (1), metabolic (1), acute cerebrovascular disease (3), remote cerebrovascular disease (5), CNS tumour (2), and undetermined (1).

Regarding progression, we found no significant differences between patients experiencing SE due to reduction, discontinuation, or poor compliance with antiepileptic treatment and those with SE due to other aetiologies regarding rates of admission to the ICU (64.7% vs 43.3%), intubation (47.5% vs 35.8%), and systemic complications (58.8% vs 53.7%). None of the patients whose episodes had been caused by changes in drug treatment died or experienced neurological sequelae.

Likewise, differences were not significant between patients with and without a history of epilepsy in terms of admission to the ICU (56.8% vs 37.5%), intubation rates (43.2% vs 32.1%), systemic complications (59.1% vs 50%), severe sequelae (15.9% vs 22.5%), and mortality (11.4% vs 25%).

DiscussionOur retrospective study gathered data from clinical practice in 5 local hospitals and analysed the treatment and progression of different types of SE. In our sample, treatment achieved seizure control in early SE in 13.1% of the cases, in established SE in 20.2%, in refractory SE in 41.7%, and in super-refractory SE in 13.1%; 10 patients (11.9% of the episodes) died before SE could be controlled. These data indicate that SE could not be controlled within the first 2hours in nearly half of the cases. We must also be aware that the definition of SE varies according to different studies.1,9,13 SE is defined as prolonged, continuous seizure activity or 2 or more seizures without full recovery of consciousness between them. Given that our study had a retrospective design, we included patients according to their diagnosis at discharge; duration was not an inclusion criterion, although we observe that only 13.1% of the episodes resolved during the early stage (30min or less).

The literature provides several definitions for refractory SE.7,8,11 According to some studies, refractory SE accounts for 30% to 40% of all SE cases.11,14 In a recent prospective study, 22.6% of SE were refractory to first- and second-line treatment.18

In our sample, 35 episodes (41.7%) were controlled during the refractory stage; we defined refractory SE as an episode lasting more than 120minutes. Some studies define refractory SE as an episode of SE requiring anaesthesia; however, anaesthesia is not always necessary nor is it administered at such early stages in some types of SE, for example nonconvulsive SE. Intubation was necessary in 25 episodes of SE, that is, 71.4% of the cases of refractory SE and 29.76% of all episodes.

According to some researchers, 10% to 15% of all SE episodes treated in hospitals become super-refractory.19 In our sample, 13.1% of all SE were brought under control during the super-refractory stage; this rate may be somewhat higher since we did not analyse SE stages in patients who died before SE could be controlled (most of these patients had not been admitted to the ICU).

We also analysed the drug treatments employed, referring to both antiepileptics and anaesthetics. Approximately half of the episodes were successfully controlled after administering a third drug; however, some episodes required up to 8 different drugs (Fig. 1). According to treatment guidelines and consensus documents, treatment for SE may vary from country to country due to differences in drug availability.15,16,21 For example, intravenous lorazepam, a highly effective first-line drug, is not available in Spain unlike such other benzodiazepines as diazepam, clonazepam, and midazolam. Likewise, other antiepileptics such as fosphenytoin, whose safety profile is better than that of phenytoin, are not marketed in Spain.

We only gathered data on the number of drugs administered, whether antiepileptics or anaesthetics, but did not record doses or which lines of treatment achieved seizure control. However, we feel that these variables should be analysed separately for each type of SE. Our results show that once first-line drugs fail to control seizures, success rates for each additional treatment decrease progressively, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Our study has several limitations, including its retrospective design and its small sample size, which may have resulted in failure to detect significant differences between some aetiologies or SE types. Likewise, although there were no instances of neurological sequelae in any of the patients who experienced SE due to treatment reduction, discontinuation, or poor compliance, the limits of the retrospective data collection method may explain these results.

SE could not be controlled in the first 2hours in nearly half of the cases; no differences were found with regard to types of SE. Although approximately half of the episodes were controlled with the third drug, some cases required as many as 8 drugs. This retrospective study does not compare doses, time of administration of each drug, or number of concomitant drugs. Furthermore, our study includes different types of SE and various aetiologies (for example, progressive neurological disorders); therefore, the effectiveness of treatment lines in our sample cannot be compared to findings reported by other studies.

Regarding progression, admission to the ICU and systemic complications were more frequent in patients with tonic–clonic SE than in those with complex partial SE; however, SE type did not seem to affect sequelae and mortality rates.

Despite advances in epilepsy diagnosis and treatment, such as the development of intravenous antiepileptic drugs, designing studies of SE entails a number of methodological difficulties.6,17 New SE registers should include data on SE type and aetiology of SE so that we can evaluate the effectiveness of different treatment lines and prognosis for each type of SE, considering the aetiology and presence or absence of a history of epilepsy.

FundingThis study has received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: de la Morena Vicente MA, Granizo Martínez JJ, Ojeda Ruiz de Luna J, Peláez Hidalgo A, Luque Alarcón M, Navacerrada Barrero FJ, et al. Estudio observacional multicéntrico retrospectivo sobre el manejo clínico y terapéutico de los diferentes tipos de estatus epiléptico en la práctica clínica. Neurología. 2017;32:284–289.