“Your squire Guadiana, lamenting your hard fate, was in like manner metamorphosed into a river that bears his name; yet still so sensible of your disaster, that when he first arose out of the ground, to flow along its surface, and saw the sun in a strange hemisphere, he plunged again into the bowels of the earth; but the natural current forcing a passage up again, he reappears again and again...”1 Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

Pseudocclusion of the internal carotid artery (ICA) is the consequence of a large atheromatous lesion causing high-degree stenosis. This lesion is commonly located in the proximal segment of the ICA or at the level of the carotid bifurcation, giving rise to a filiform flow in the distal portion followed by recovery of its normal lumen.2

In 1967, Davies and Sutton were the first to refer to a slowing of the carotid flow in the context of their study of intracranial hypertension.3 Lippman et al.4 described an atherosclerotic lesion in the ICA and distinguished it from carotid hypoplasia.

Pseudocclusions may result from carotid dissection, whether traumatic or spontaneous, or else from stenosis secondary to a radiation-induced arteritis, congenital carotid hypoplasia, or a severe diffuse atheromatous lesion extending distally5 and mimicking a complete occlusion. This erroneous impression frequently arises when the working diagnosis has been determined using a single non-invasive imaging technique which does not enable reliable identification of a critical stenosis or pseudocclusion of the ICA. Combining several non-invasive techniques to study an apparent occlusion increases their diagnostic ability considerably, with no need for such invasive techniques as angiography. However, radiological findings characteristic of a carotid pseudocclusion have classically been defined by angiography, and they are traditionally grouped under the term ‘carotid string sign’.

Carotid string signThe radiological terms ‘carotid slim sign’ or ‘carotid string sign’ refer to the angiographic finding of a critical stenosis of approximately 99%, located at the root of the ICA, with preserved patency of the threadlike distal segment.2

Many diverse and different findings have been included under the umbrella term ‘string sign’: from carotid artery disease (mentioned above) to the narrowing, frayed appearance of the terminal ileum in the context of inflammatory bowel disease. In neurology, and especially in the field of stroke, the term ‘string sign’ is usually associated with a hyperdense artery during ischaemic stroke in the hyperacute stage. Even so, questions remain about the validity of using a catch-all heading under which such different diseases are included.

Guadiana riverThe seeming disappearance and distal reappearance of blood flow, which are characteristic of carotid pseudooclusion, are reminiscent of the ‘hidden’ course of the Guadiana river, the Iberian peninsula's fourth greatest river in terms of length and discharge. It runs east to west from Castille-La Mancha across Andalusia to reach Extremadura, where it finally turns south to mark the Spanish-Portuguese border before flowing into the Atlantic Ocean. The course of the river disappears in the vicinity of the town of Argamasilla de Alba (Castille-La Mancha) to later reappear through natural apertures, such as those located near Villarrubia de los Ojos, gateway to the springs known as the “Ojos del Guadiana”. The river's underground course is explained by the multiple cracks in the rocks which enable the water to flow through an aquifer system before reaching the surface again.6

Clinical caseTo illustrate the Guadiana river sign, we present the case of a 64-year old man who awakened suddenly with a severe headache irradiating to the right cervical region, followed by dysarthria and transient left-side weakness which was predominantly faciobrachial. Symptoms resolved within an hour. His medical history included arterial hypertension and smoking until the age of 40. The cranial CT scan yielded normal results, as did the routine blood test, the electrocardiogram, and the echocardiogram.

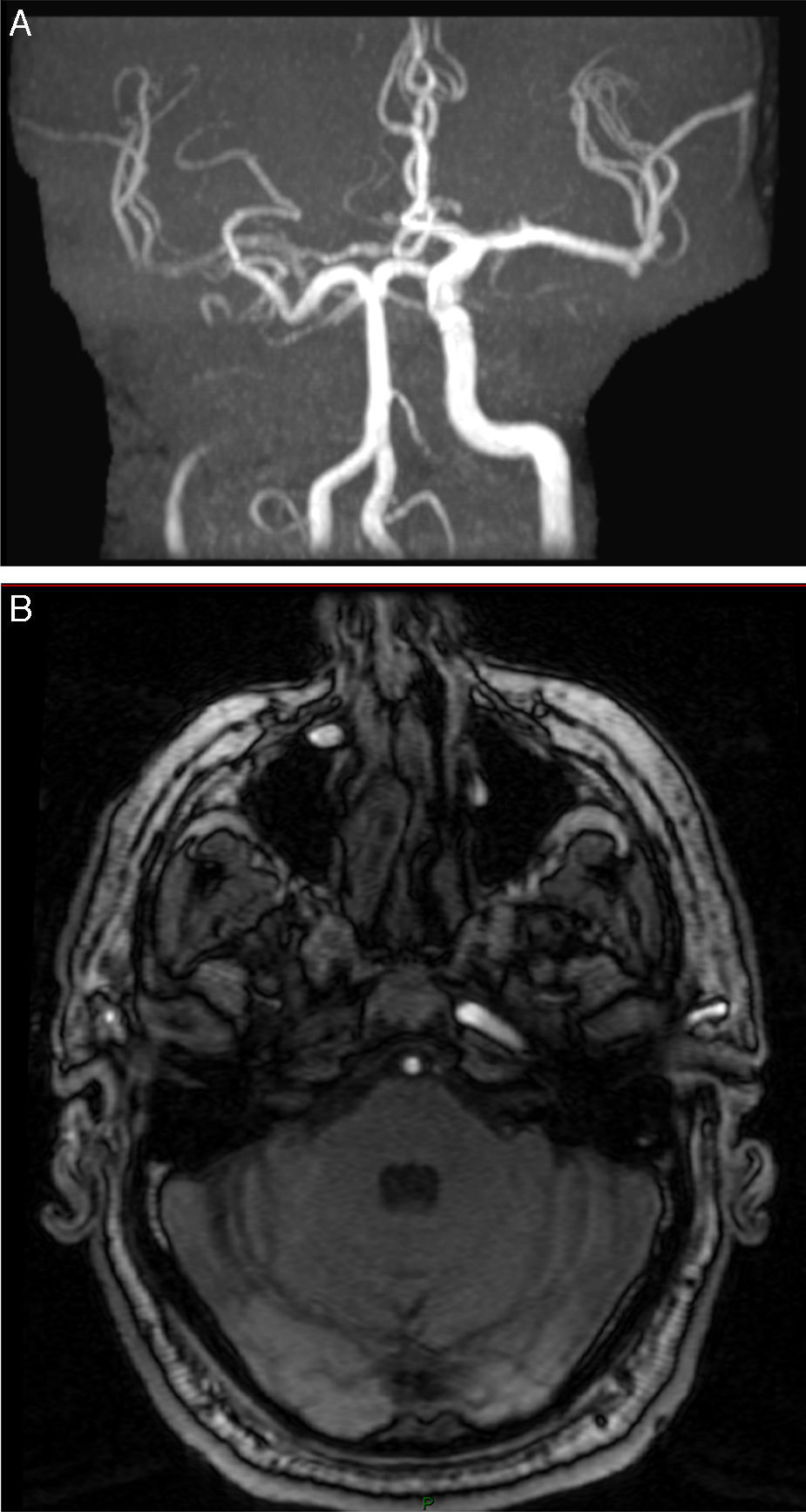

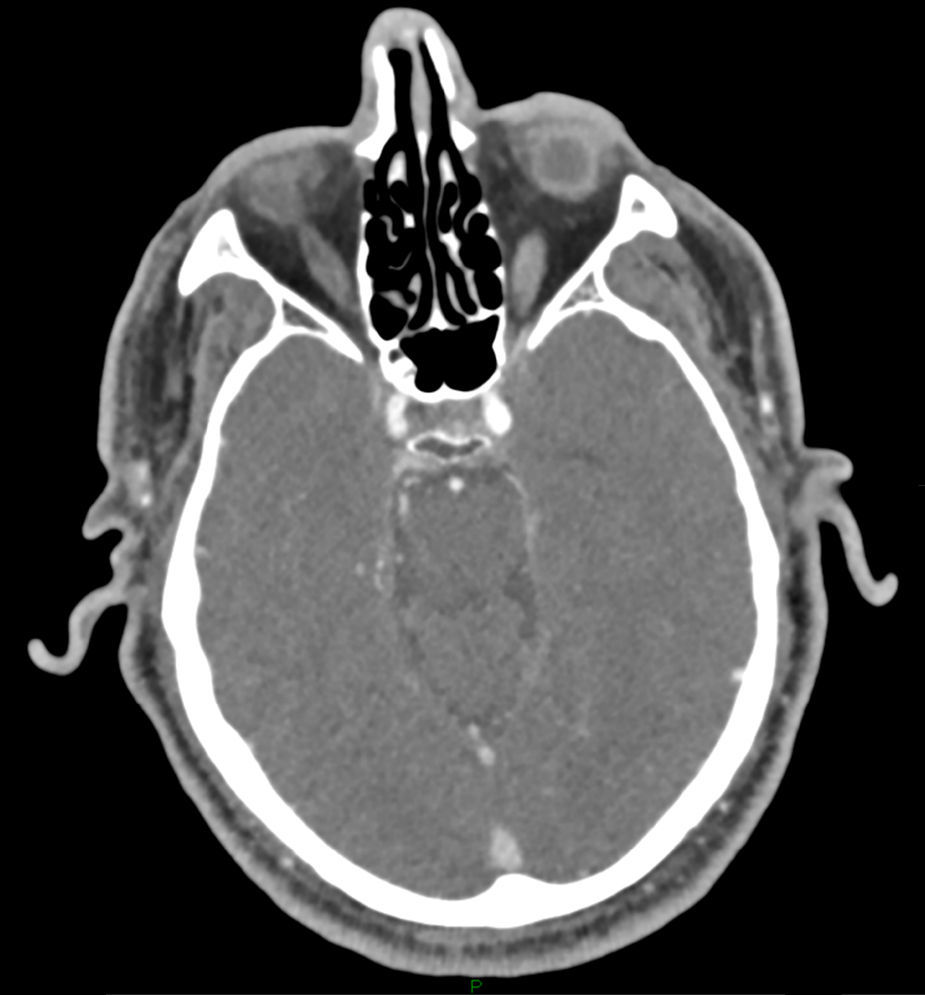

The carotid Doppler ultrasound revealed an apparent distal occlusion of the ICA, with no signs of dissection, contrary to our initial clinical suspicion. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed punctiform ischaemic foci in the right cerebral hemisphere at the prefrontal, temporoparietal, and parieto-occipital levels. The MR angiography (MRA) of the neck showed an occlusion of the right ICA at the level of the carotid sinus, 5mm from its root, with absence of flow at the base of the skull. We also observed that the diameter of the external carotid artery was comparatively larger, but no signs of dissection were seen on time-of-flight sequences. The intracranial MRA showed a pattern characteristic of collateral circulation in the context of an apparent occlusion of the right ICA. This circulation passed through the anterior communicating artery, with antidromic flow of the anterior cerebral artery filling the middle cerebral artery, which appears attenuated; collateral circulation is lacking in the right posterior cerebral artery (Fig. 1 A and B). Sequential CT angiography showed high-degree stenosis of the ICA with the seeming disappearance and subsequent reappearance of blood flow. It also revealed the presence of critical stenosis >99% affecting the distal portion of the carotid sinus. Stenosis was associated with a calcified atherosclerotic plaque; the intraluminal filling defect disappeared and flow was observed at the level of the cavernous sinus (Fig. 2).

(A, B) Nuclear MRA shows an apparent occlusion of the right internal carotid artery at the level of the carotid sinus 5mm from its root and absence of flow at the base of the skull. The images show a collateral circulation pattern passing through the right anterior communicating artery, with antidromic flow in the anterior cerebral artery filling the ipsilateral middle cerebral artery, which appears attenuated. Collateral circulation is absent in the right posterior cerebral artery.

After the initial cranial CT scan, the patient received triple antiplatelet therapy as a participant in a clinical trial comparing triple therapy to standard antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention of minor ischaemic stroke and high-risk transient ischaemic attacks. In view of these findings, a right thromboendarterectomy was performed at 30 days. The patient remains asymptomatic to date, and his treatment consists exclusively of clopidogrel 75mg, atorvastatin 40mg, and quinapril 5mg.

DiscussionThe NASCET criteria for measuring carotid stenosis tend to underestimate the degree of severity of pseudocclusions since the diameter of the ICA decreases as the degree of obstruction increases. Therefore, some authors have proposed using exclusively angiographic and qualitative criteria to identify pseudocclusion of the ICA.7 These criteria include: an ICA with a diameter smaller than that of the external carotid; opacification in the distal territory of the ICA, which again would be smaller than the external carotid; and compensation by means of collateral intracranial circulation.8

Collapse of the distal ICA caused by atherosclerotic plaque, observed during surgical examination of the neck, represents the main feature in carotid pseudocclusion; the treatment of choice is thromboendarterectomy.9 Despite the important advances in such non-invasive imaging techniques as Doppler ultrasound, MRA, and CT angiography, conventional angiography or arteriography is still considered the most accurate diagnostic method or gold standard with which to examine this phenomenon. However, newly-developed non-invasive techniques provide sufficiently valid information, especially when used in combination, to let us distinguish between complete occlusion and pseudocclusion in clinical practice without any need for more invasive methods.

Nevertheless, usefulness of conventional angiography in specific cases should not be underestimated. Portuguese neurosurgeon António Egas Moniz (1874–1955) developed the ‘arterial encephalography’ method which resulted in several well-known clinical applications. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine not for that innovation, but rather for his pioneering studies of psychosurgery in which he treated psychosis with prefrontal leucotomy. The latter technique was later optimised and polished when he returned to the Iberian Peninsula to work with the great Basque neurosurgeon Juan Burzaco Santurtún (1930–2006). In 1928, Ferrán Martorell became the first doctor in Spain to perform an angiography following Egas Moniz's method.10

The use of angiography over the years continues in the procedures routinely employed in current practice: for example, thrombolysis during the acute phase of ischaemic stroke or angioplasty as an interventional therapeutic alternative to thromboendarterectomy. Among non-interventional radiology techniques, MRA and time-of-flight sequences alone are not currently able to calculate the minimum residual flow precisely enough to identify presence of critical stenosis, that is, presence of a carotid pseudocclusion treatable by surgery. However, these techniques are more reliable when combined with each other or with other techniques.11,12

Guadiana river signCurrently, there is no consensus on the term used to refer to pseudocclusion of the ICA, an entity also known as subocclusion, preocclusion, or critical stenosis. The most widely accepted term is ‘string sign’, despite the multiple meanings that we mentioned previously. We believe that the concept of a river whose course disappears and later reappears, similarly to what occurs in carotid pseudocclusion, is more explanatory. With the above in mind, and considering the waning use of conventional angiography studies for presurgical evaluation of ICA and the frequent references to a ‘string sign’ in other fields of vascular neurology or medicine, we suggest ‘Guadiana river sign’ as a term for carotid pseudocclusion.

The Guadiana river, whose underground course was described by Cervantes, is a metaphor evoking the seeming disappearance and subsequent reappearance of vascular flow that characterises a carotid pseudocclusion. A sign by this name pays tribute to Don Quixote, that masterpiece of universal literature whose second part recently celebrated its four hundredth year.

FundingThe authors have received no funding for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Iniesta I, Lamballe A, Rodríguez M, Duignan J, Zaman S, Watson I, et al. Hallazgos radiológicos de una pseudooclusión carotídea sintomática: signo del Guadiana. Neurología. 2017;32:334–337.

This article is an extended version of the poster communication titled “Clinico-Radiological features of a symptomatic subocclusive carotid stenosis: Guadiana river sign” presented at the 9th World Stroke Congress held in Istambul, 22–24 October 2014.